Abstract

Six VanB phenotype-vanA genotype isolates of Enterococcus faecium with heterogeneous expression of teicoplanin resistance which gave rise to an outbreak at a Korean tertiary care teaching hospital have IS1216V in the coding region of vanS. This could be the underlying cause of the VanB phenotype-vanA genotype with heterogeneous expression of teicoplanin resistance.

VanA glycopeptide resistance is characterized by acquired inducible resistance to both vancomycin and teicoplanin, whereas the VanB phenotype is characterized by variable levels of resistance to vancomycin but susceptibility to teicoplanin (1, 5). During the past 5 years, vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE) with the vanA genotype that are susceptible to teicoplanin, hence having the VanB phenotype and the vanA genotype, have become increasingly prevalent in Asia (8, 11, 12). In 2005, we experienced an outbreak of VanB phenotype-vanA genotype Enterococcus faecium strains with heterogeneous expression of teicoplanin resistance isolated from six patients at a tertiary care teaching hospital. To our knowledge, this is the first description of IS1216V inserted in the coding region of the vanS gene that might be involved in the heterogeneous expression of teicoplanin susceptibility.

From November to December 2005, six VanB phenotype-vanA genotype E. faecium isolates (AJJ2, AJJ3, AJJ4, AJJ5, AJJ8, and AJJ10) were collected from a tertiary care teaching hospital. The organisms were identified by using conventional biochemical reactions and a Vitek identification system (bioMérieux, Hazelwood, MO). To evaluate the genetic relatedness of the isolates, pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) was performed with SmaI-digested genomic DNA (Gibco BRL, Gaithersburg, MD) as described by Murray et al. (13), with pulse times beginning with 1 s and ending with 20 s at 6 V/cm for 24 h. Dendrograms based on Dice coefficients and clustered using an unweighted-pair group method using an arithmetic averages algorithm were generated with Bio-Gene software (Vilber Lourmat, Marne-la-Vallée, France). All six VanB phenotype-vanA genotype E. faecium isolates revealed identical or closely related PFGE patterns according to the method of Tenover et al. (14). The MICs of vancomycin and teicoplanin for the isolates were determined by Etest (AB Biodisk North America, Inc., Culver City, CA). Previously characterized VRE strains, E. faecium BM4147 (3) and VanB phenotype-vanA genotype E. faecium JC03 (12) without heterogeneous expression of teicoplanin resistance, served as controls.

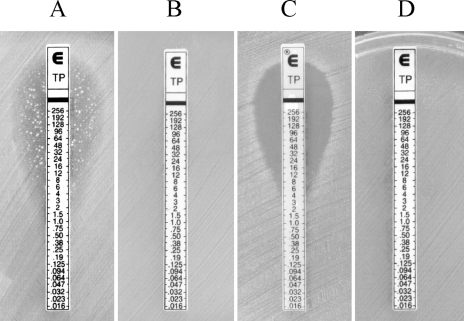

All isolates displayed various levels of vancomycin resistance (MICs, 64 to 128 μg/ml) and teicoplanin susceptibility (MICs, 4 to 12 μg/ml) with heterogeneous expression of teicoplanin resistance. The heterogeneous expression of resistance was characterized by the growth of colonies in the elliptic inhibition zone during Etest susceptibility testing (Fig. 1A). Colonies in the elliptic inhibition zone displayed a homogeneous phenotype of resistance to teicoplanin when retested by Etest (Fig. 1B). VanB phenotype-vanA genotype E. faecium JC03 (12) without heterogeneous expression of teicoplanin resistance presented teicoplanin susceptibility and displayed no growth of colonies in the inhibition zone (Fig. 1C), and E. faecium BM4147 (3) displayed a homogeneous resistance to teicoplanin (Fig. 1D).

FIG. 1.

Teicoplanin (TP) MIC determination by Etest of E. faecium AJJ5 with heterogeneous expression of teicoplanin resistance (A), a colony of E. faecium isolate AJJ5 grown in the inhibition zone next to the Etest strip (B), VanB phenotype-vanA genotype E. faecium JC03 without heterogeneous expression of teicoplanin resistance (C), and E. faecium BM4147 (D).

Bacterial DNA was extracted with a Qiagen DNeasy kit (Qiagen GmbH, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions. For structural analysis of Tn1546-like elements, an overlapping PCR amplification of internal regions of Tn1546 was performed as described previously (9). PCR amplicons larger than that of the prototype vanA gene cluster were purified with Geneclean kits (Qbiogene, Inc., Carlsbad, CA). The purified PCR products were sequenced directly by using an ABI Prism 3100 DNA sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). DNA fragments amplified with a combination of Tn1546 primer and IS1216V primer were also purified and subsequently sequenced to determine the exact integration site and orientation of the IS1216V insertion. DNASIS for Windows, version 2.6 (Hitachi Software Engineering, South San Francisco, CA), was used for sequence analysis. Nucleotide sequences were compared to the reference sequence of transposon Tn1546 (GenBank accession number M97287) (3).

Filter matings were performed with Enterococcus faecalis JH2-2 (10) as the recipient and all six isolates as the donors, as previously described (15). Transconjugants were selected on brain heart infusion (BHI) agar plates containing 50 μg/ml of rifampin, 20 μg/ml of fusidic acid, and 10 μg/ml of vancomycin. The transconjugants were examined for the structural analysis of Tn1546.

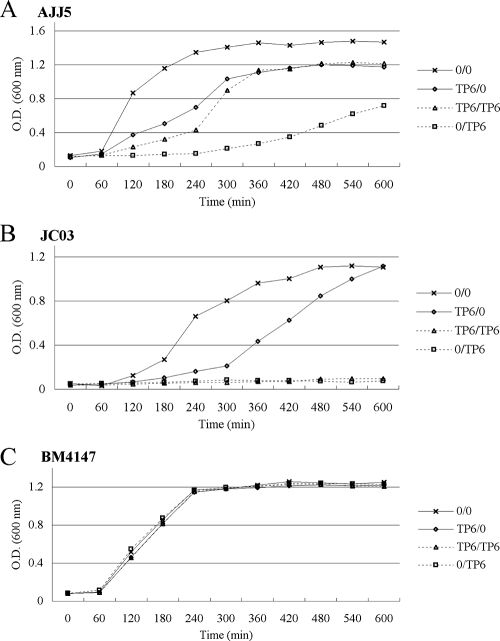

The induction of resistance to teicoplanin in VanB phenotype-vanA genotype E. faecium AJJ5 with heterogeneous expression was studied by the determination of growth rates after overnight incubation with or without teicoplanin. The isolate was grown overnight at 37°C in BHI broth with or without teicoplanin (6 μg/ml). The cultures were diluted 1:20 into 20 ml of BHI with or without teicoplanin (6 μg/ml), grown at 37°C with shaking, and monitored for their optical density at 600 nm. Previously characterized VRE strains, E. faecium BM4147 (3) and VanB phenotype-vanA genotype E. faecium JC03 (12) without heterogeneous expression of teicoplanin resistance, served as controls.

A total of 12 isolates (six original isolates and six resistant derivatives obtained from the elliptic inhibition zone on an Etest strip, respectively) were characterized by one copy of IS1216V in the left end of Tn1546, a second in the coding region of vanS, and a third in the vanX-vanY intergenic region, as well as IS1542 in the orf2-vanR intergenic region. IS1216V in vanS was integrated at nucleotide 4900 with an 8-bp duplication of the target sequence (GTCATTAG) in the forward orientation. Although the VanS sensor peptide was reported earlier to have no functional effect due to the disruption of vanS by IS1216V (6), IS1216V in the coding region of vanS in our cases might affect the expression of teicoplanin resistance. The VanRSA system activates transcription of the resistance genes in response to vancomycin and teicoplanin, whereas VanB-type enterococci remain susceptible to teicoplanin, which is not an inducer (2, 7). Amino acid substitutions due to the three point mutations of vanS are responsible for impaired teicoplanin resistance among vanA genotype VRE strains (8). On the other hand, the modification of signal transduction due to substitutions in the putative linker of VanSB has been shown to be the most common mechanism of acquisition of inducible resistance to teicoplanin among vanB genotype VRE strains (4). Similarly, the genetic alteration of vanS due to the IS1216V insertion in our isolates might be associated with heterogeneous teicoplanin resistance.

All isolates transferred vancomycin resistance, at frequencies of 6 × 10−9 to 2 × 10−8 transconjugants per donor. The transconjugants revealed the same heterogeneous resistance to teicoplanin.

In the growth rate studies, after overnight incubation of AJJ5 with teicoplanin, growth was delayed at the beginning of the subculture in the presence of teicoplanin, with growth resuming after a lag phase of 4 h (Fig. 2A). The growth of VanB phenotype-vanA genotype E. faecium JC03 without heterogeneous expression of teicoplanin resistance was suppressed throughout the subculture in the presence of teicoplanin, regardless of prior overnight incubation (Fig. 2B). The growth of BM4147 did not show any lag phase throughout the subcultures either in the absence or presence of teicoplanin, regardless of prior overnight incubation (Fig. 2C). The resumption of growth of AJJ5, which is characterized by an IS1216V insertion in the coding region of the vanS gene, in the presence of teicoplanin after overnight incubation with teicoplanin and the homogeneous expression of teicoplanin resistance in a colony within the inhibition zone suggest that a portion of bacteria that retained teicoplanin resistance were fully induced after incubation with teicoplanin.

FIG. 2.

Effect of overnight growth in the presence of teicoplanin (6 μg/ml; TP6) on E. faecium AJJ5 with heterogeneous expression of teicoplanin resistance (A), VanB phenotype-vanA genotype E. faecium JC03 without heterogeneous expression of teicoplanin resistance (B), and E. faecium BM4147 (C) in the absence (0) or presence of teicoplanin. Teicoplanin concentration in the overnight culture/in the subculture medium. O.D., optical density.

The heterogeneous teicoplanin resistance of our isolates was clinically important because the conventional test cannot detect heterogeneous teicoplanin resistance. These isolates might potentially give rise to homogeneous resistance during teicoplanin therapy. The results of PFGE showed genetically identical or closely related patterns for all isolates, indicating clonal distribution (14). When VanB phenotype-vanA genotype E. faecium strains are found, molecular typing and MIC determination by Etest are recommended during teicoplanin therapy to prevent a nosocomial outbreak.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant (06042KFDA126) from the Korea Food and Drug Administration in 2006.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 2 July 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arthur, M., and P. Courvalin. 1993. Genetics and mechanisms of glycopeptide resistance in enterococci. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 371563-1571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arthur, M., F. Depardieu, P. Reynolds, and P. Courvalin. 1996. Quantitative analysis of the metabolism of soluble cytoplasmic peptidoglycan precursors of glycopeptide-resistant enterococci. Mol. Microbiol. 2133-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arthur, M., C. Molinas, F. Depardieu, and P. Courvalin. 1993. Characterization of Tn1546, a Tn3-related transposon conferring glycopeptide resistance by synthesis of depsipeptide peptidoglycan precursors in Enterococcus faecium BM4147. J. Bacteriol. 175117-127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baptista, M., P. Rodrigues, F. Depardieu, P. Courvalin, and M. Arthur. 1999. Single-cell analysis of glycopeptide resistance gene expression in teicoplanin-resistant mutants of a VanB-type Enterococcus faecalis. Mol. Microbiol. 3217-28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clark, N. C., R. C. Cooksey, B. C. Hill, J. M. Swenson, and F. C. Tenover. 1993. Characterization of glycopeptide-resistant enterococci from U.S. hospitals. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 372311-2317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Darini, A. L., M.-F. I. Palepou, D. James, and N. Woodford. 1999. Disruption of vanS by IS1216V in a clinical isolate of Enterococcus faecium with VanA glycopeptide resistance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43995-996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Evers, S., and P. Courvalin. 1996. Regulation of VanB-type vancomycin resistance gene expression by the VanS(B)-VanR (B) two-component regulatory system in Enterococcus faecalis V583. J. Bacteriol. 1781302-1309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hashimoto, Y., K. Tanimoto, Y. Ozawa, T. Murata, and Y. Ike. 2000. Amino acid substitutions in the VanS sensor of the VanA-type vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus strains result in high-level vancomycin resistance and low-level teicoplanin resistance. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 185247-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huh, J. Y., W. G. Lee, K. Lee, W. S. Shin, and J. H. Yoo. 2004. Distribution of insertion sequences associated with Tn1546-like elements among Enterococcus faecium isolates from patients in Korea. J. Clin. Microbiol. 421897-1902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jacob, A. E., and S. J. Hobbs. 1974. Conjugal transfer of plasmid-borne multiple antibiotic resistance in Streptococcus faecalis var. zymogenes. J. Bacteriol. 117360-372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lauderdale, T. L., L. C. McDonald, Y. R. Shiau, P. C. Chen, H. Y. Wang, J. F. Lai, and M. Ho. 2002. Vancomycin-resistant enterococci from humans and retail chickens in Taiwan with unique VanB phenotype-vanA genotype incongruence. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46525-527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee, W. G., J. Y. Huh, S. R. Cho, and Y. A. Lim. 2004. Reduction in glycopeptide resistance in vancomycin-resistant enterococci as a result of vanA cluster rearrangements. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 481379-1381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Murray, B. E., K. V. Singh, J. D. Heath, B. R. Sharma, and G. M. Weinstock. 1990. Comparison of genomic DNAs of different enterococcal isolates using restriction endonucleases with infrequent recognition sites. J. Clin. Microbiol. 282059-2063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tenover, F. C., R. D. Arbeit, R. V. Goering, P. A. Mickelsen, B. E. Murray, D. H. Persing, and B. Swaminathan. 1995. Interpreting chromosomal DNA restriction patterns produced by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis: criteria for bacterial strain typing. J. Clin. Microbiol. 332233-2239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Trieu-Cuot, P., C. Carlier, and P. Courvalin. 1988. Conjugative plasmid transfer from Enterococcus faecalis to Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 1704388-4391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]