Abstract

Microsporidia are obligate intracellular parasites that are ubiquitous in nature and have been recognized as causing an important emerging disease among immunocompromised individuals. Limited knowledge exists about the immune response against these organisms, and virtually nothing is known about the receptors involved in host recognition. Toll-like receptors (TLR) are pattern recognition receptors that bind to specific molecules found on pathogens and signal a variety of inflammatory responses. In this study, we show that both Encephalitozoon cuniculi and Encephalitozoon intestinalis are preferentially recognized by TLR2 and not by TLR4 in primary human macrophages. This is the first demonstration of host receptor recognition of any microsporidian species. TLR2 ligation is known to activate NF-κB, resulting in inflammatory cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) and interleukin-8 (IL-8). We found that the infection of primary human macrophages leads to the nuclear translocation of NF-κB in as early as 1 h and the subsequent production of TNF-α and IL-8. To verify the direct role of TLR2 parasite recognition in the production of these cytokines, the receptor was knocked down in primary human macrophages using small interfering RNA. This knockdown resulted in decreases in both the nuclear translocation of NF-κB and the levels of TNF-α and IL-8 after challenge with spores. Taken together, these experiments directly link the initial inflammatory response induced by Encephalitozoon spp. to TLR2 stimulation in human macrophages.

Microsporidiosis has been reported as the cause of chronic and life-threatening diseases in human immunodeficiency virus/AIDS patients and organ recipients and, therefore, has gained a greater medical importance among individuals who have an impaired immune status (4, 8, 32, 36). Increasingly, infections involving immunocompetent individuals, particularly those affecting the elderly or young, have also been reported (8, 10, 24, 31). Infections are believed to occur primarily through the ingestion of microsporidian spores and proceed through the invasion of enterocytes in the small intestine (8). Clinical reports of microsporidiosis have described a range in the severity of the disease, from intestinal infections leading to chronic diarrhea to disseminated diseases thought to occur as a result of migrating macrophages, including keratoconjunctivitis, sinusitis, tracheobronchitis, encephalitis, interstitial nephritis, hepatitis, cholecystitis, osteomyelitis, and myositis (8, 18, 32, 36).

Microsporidia comprise a group of more than 1,200 species of obligate intracellular pathogens that can be found virtually everywhere in nature and are able to infect a wide variety of vertebrate and invertebrate organisms (2, 8, 13, 16). These parasites were once classified as protozoa; however, recent phylogenetic analysis has revealed their close association with fungi (8, 16). The infective stage of the parasite is an environmentally resistant spore that is believed to infect cells through the eversion of a unique polar filament which structurally distinguishes microsporidia from other spore-forming organisms (2, 8, 13). The polar filament functions similarly to a syringe and needle by penetrating the host membrane and forcing the sporoplasm through the tube and into the host cell (2, 8, 13, 42). For macrophages, infection has been reported to occur via phagocytosis of the infectious spore (11). However, the specific mechanism of macrophage recognition of these spores has not been reported.

Host recognition of pathogens is accomplished by a diverse repertoire of germ line-encoded proteins called pattern recognition receptors. Toll-like receptors (TLR) represent a unique collection of evolutionarily conserved pattern recognition receptors known to recognize pathogen-associated molecular patterns found on viruses, bacteria, parasites, and fungi. Ten TLR have been identified in humans and are known to recognize molecular moieties, such as peptidoglycan and zymosan by TLR2 or lipopolysaccharide (LPS) by TLR4 (23, 37). The engagement of TLR has been shown to activate a variety of intracellular signaling pathways, including the MyD88-dependent pathway which ultimately activates the transcriptional factor NF-κB (23, 26, 37). The activation and nuclear translocation of NF-κB are implemented in the transcription of many inflammatory cytokines and chemokines needed for the successful clearance of the pathogen and the recruitment of immune cells, including tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) and interleukin-8 (IL-8) (6, 22).

Since the discovery of TLR, their recognition of molecular patterns on bacteria and viruses has been well documented. More recently, a number of protozoan and fungal organisms that share structural and/or biological similarities with microsporidia have also been linked with TLR activation. Cryptosporidium parvum, an oocyst-forming protozoan that typically infects the small intestine, recruits both TLR2 and TLR4 and activates NF-κB signaling in human cholangiocytes (5). Genomic analysis of Encephalitozoon spp. has predicted that the spore coats may contain glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) anchors (33, 41), which recently have also been considered key molecules isolated from Toxoplasma gondii and Trypanosoma cruzi and shown to signal through TLR2 and TLR4 (3, 7). Additionally, TLR have been shown to recognize highly conserved fungal cell wall components, such as glucans, chitin, and mannoproteins from Candida and Aspergillus organisms, which share some similarities to recently identified microsporidian spore coat molecules (28, 29).

To date, there is limited information about the host's innate immune response to microsporidia, and no information exists about the role of TLR in the recognition of these parasites. However, studies involving microsporidian infection have provided some evidence that suggests the involvement of NF-κB. Analyses of culture supernatants from primary human macrophages challenged with Encephalitozoon spores revealed increases in the levels of the cytokine TNF-α (14) and the chemokines CCL3, CCL4, and CCL2 in response to infection (12). Taken together, these reports of inflammatory mediator production and the previously described biological similarities between microsporidia and pathogens that are known to activate TLR suggest that microsporidia may also be recognized by and elicit a TLR response.

The present study has explored the role of TLR in macrophage host defense against microsporidian parasites. We report that both Encephalitozoon cuniculi and Encephalitozoon intestinalis are recognized by TLR2. In addition, parasite challenge leads to the nuclear translocation of NF-κB, which is required for TNF-α and IL-8 production. To our knowledge, this is the first study that demonstrates a role for TLR in the innate immune response to any species of microsporidia.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents.

Lymphocyte separation medium, fetal calf serum (FCS), l-glutamine, gentamicin, penicillin, and streptomycin were purchased from Cambrex (Walkersville, MD), and Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM), phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and Greiner Bio-One Cellstar tissue culture plates were obtained from VWR International (West Chester, PA). LPS from Escherichia coli O111:B4 was obtained from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO), and Pam3CSK4 was obtained from Axxora (San Diego, CA). Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) reagents and antibodies, goat anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 488, and Lipofectamine 2000 were purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA), and anti-NF-κBp65 was obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Santa Cruz, CA). The NF-κB inhibitor (Bay11-7085), all validated real-time quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) primers, and RT2 Sybr green-fluorescein master mix were obtained from SuperArray (Frederick, MD). Predesigned TLR2 and control oligonucleotides were purchased from Ambion (Foster City, CA).

Cell culture.

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells were isolated from buffy coats of healthy donors (Our Lady of the Lake Regional Blood Bank, Baton Rouge, LA) by gradient centrifugation on lymphocyte separation medium according to guidelines established by the Internal Review Board (Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, LA). Monocyte-derived macrophages (MDM) were obtained by adherence assays, as previously reported (12). Briefly, monocytes were plated onto 6-well (2 × 106 cells/well), 24-well (5 × 105 cells/well), and 96-well (1 × 105 cells/well) culture plates and cultured for 3 h in supplemented DMEM containing 2 mM l-glutamine, 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, and 0.1 μg/ml gentamicin at 37°C in 5% CO2. Cells were stringently washed with PBS to remove nonadhered peripheral blood mononuclear cells and then allowed to differentiate for 7 days in supplemented DMEM with 10% FCS at 37°C in 5% CO2. Some MDM were plated in 24-well culture plates with cover glasses.

Parasites.

Encephalitozoon cuniculi III and E. intestinalis (a generous gift from Elizabeth Didier, Tulane National Primate Research Center, Covington, LA) were grown in a rabbit kidney cell line (ATCC CCL-37) in DMEM supplemented with 10% FCS at 37°C in 5% CO2 and harvested from tissue culture supernatants. Spores were washed once in PBS containing 0.2% Tween 20, resuspended in supplemented DMEM, and counted with a hemacytometer (9). Spores were used at a 5:1 spore-to-MDM ratio (12). Some spores were heat inactivated in a 95°C water bath for 30 min.

TLR-transfected HEK cell lines.

Human embryonic kidney (HEK) cell lines transfected with TLR2, TLR4, TLR4/MD2/CD14, or null plasmids (InvivoGen, San Diego, CA) were grown in 96-well culture plates in supplemented DMEM with 10% FCS at 37°C in 5% CO2. Confluent cultures were challenged with spores of E. cuniculi or E. intestinalis, and supernatants were collected and analyzed by ELISA for TLR activation via IL-8 production, as suggested by the manufacturer. As controls, some cultures were stimulated with the TLR4 or TLR2 agonist LPS (10 ng/ml) or Pam3CSK4 (50 ng/ml), respectively.

RT-qPCR.

Total RNA was isolated from 1 × 107 E. cuniculi- or E. intestinalis-infected MDM grown in six-well culture plates using the Qiagen RNeasy minikit (Valencia, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions, quantified with a NanoDrop (Wilmington, DE) ND-1000 spectrophotometer, and assessed for quality with an Experion automated electrophoresis system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Reverse transcription was performed with SuperScript III first-strand synthesis supermix (Invitrogen). RT-qPCR was performed using a Bio-Rad iCycler according to the manufacturer's instructions. The amplification of TNF-α, TLR2, and TLR4 cDNA was completed using validated primers and the RT2 Sybr green-fluorescein master mix. All data were normalized to the β-actin housekeeping gene, and gene expression was calculated as previously described (21). Briefly, the cycle threshold (CT) value (log2) for β-actin minus the CT value of the gene of interest for each sample (ΔCT = CT of β-actin − CT of gene of interest) was calculated and is presented as the percentage of β-actin.

Immunofluorescence detection of nuclear NF-κB.

Adherent cells on cover glasses were challenged with Encephalitozoon spores or LPS (10 ng/ml) for 1 or 6 h, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, and permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS. Cells were then incubated with Image-iT FX signal enhancer (Invitrogen) for 30 min at RT followed by polyclonal rabbit anti-mouse NFκBp65 (1:50 dilution) overnight at 4°C. The cells were extensively washed in PBS and then incubated with goat anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 488 (1:200 dilution) for 60 min at RT, washed again, and mounted in ProLong gold medium (Invitrogen). Cells were examined using a Leica DMI 6000 B inverted fluorescence microscope and captured and analyzed with a Leica DFX300 FX charge-coupled-device camera and Image Pro Plus v5.1 software, respectively (Media Cybernetics, Silver Spring, MD).

ELISA.

Supernatants were collected from MDM cultures at specified times postinfection with E. cuniculi or E. intestinalis and analyzed for TNF-α, IL-8, CCL3, and CCL4 cytokine/chemokine production as per the manufacturer's instruction. Nuclear extracts were collected and assayed for the translocation of NF-κB by following the manufacturer's protocol. The samples were assayed in duplicate. In some experiments, 20 μM of the NF-κB inhibitor, Bay11-7085, was added to cell cultures 1 h prior to infection. The colometric determination of values was performed on a VersaMax microplate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA) and analyzed using SoftMax Pro software (Molecular Devices).

siRNA.

Three TLR2 small interfering RNA (siRNA) sequences were equally mixed in each transfection, and experiments were performed as previously described (40). Briefly, MDM were seeded in 96-well plates at 1 × 105 cells per well in serum-free, supplemented DMEM. MDM were transfected with 20 pmol of siRNA and 1 μl of Lipofectamine 2000 per well. Cultures were allowed to incubate with siRNA-Lipofectamine complexes for 4 h at 37°C in 5% CO2, washed, and placed in fresh, supplemented DMEM with 10% FCS for 48 h prior to the performance of the experiments. siRNA knockdown of the specific gene was confirmed by RT-qPCR.

Statistical analysis.

Three experiments were performed at each time point and for each parasite or condition, unless otherwise stated. Each experiment consisted of a single donor and was measured in duplicate. Statistical significance was determined by one-way analysis of variance followed by Dunnett's posttest, and P values of ≤0.05 were considered significant. All error bars shown in this paper represent standard errors of the means. Analyses were performed using InStat software, version 3.0 (GraphPad, San Diego, CA).

RESULTS

TLR2 mediates the recognition of Encephalitozoon spp.

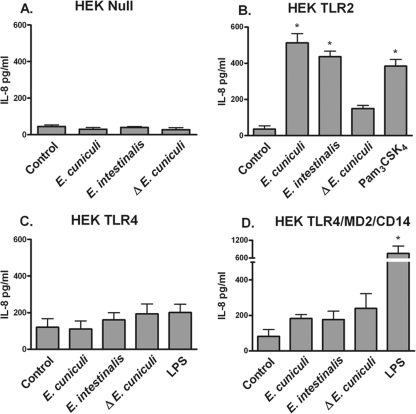

To delineate a role for TLR in the recognition of microsporidian parasites, HEK293 cells stably transfected with null plasmids or with plasmids containing TLR2, TLR4, or the complex TLR4/MD2/CD14 (confirmed in LPS recognition and signaling) were stimulated with spores from two Encephalitozoon spp. HEK293 cells do not express TLR but do contain the intracellular machinery needed to provide a response if the receptor is available. When stimulated, these transfected cells provide an NF-κB-driven IL-8 response. The HEK293 null cell line did not respond to either Encephalitozoon spp. or the TLR agonist (Fig. 1A), indicating that no native IL-8 responses were generated against the spores. The detection of IL-8 was observed in TLR2-transfected cells challenged with spores from both species and heat-killed E. cuniculi spores (Fig. 1B). Neither TLR4 alone (Fig. 1C) nor the TLR4/MD2/CD14 complex (Fig. 1D) generated a signal in response to the challenge with Encephalitozoon spores. As well, heat-killed spores did not generate a strong signal. These data suggest that spores of the Encephalitozoon species are recognized by TLR2, which could initiate subsequent inflammatory signaling and the production of mediators.

FIG. 1.

Encephalitozoon spp. are recognized by TLR2. HEK293 cells transfected with null plasmids (A) or plasmids encoding TLR2 (B), TLR4 (C), or TLR4/MD2/CD14 (D) were challenged with spores of Encephalitozoon spp., heat-inactivated (Δ) E. cuniculi, LPS (10 ng/ml), or Pam3CSK4 (50 ng/ml) overnight. Culture supernatants were collected and assessed for IL-8 production by ELISA (n = 3). *, P ≤ 0.05.

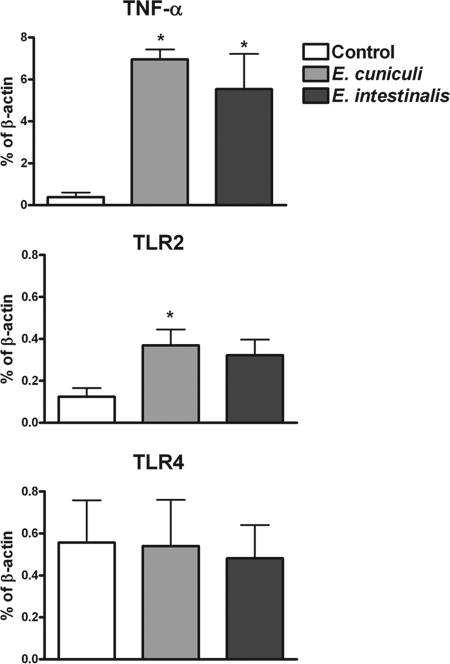

Encephalitozoon stimulation increased TLR2 expression in human primary macrophages.

While HEK293 cell lines are widely used to determine TLR responses to pathogens, it is important to establish the role of these receptors in cells which are involved in recognition of Encephalitozoon spp. in vivo. Macrophages are not only involved in innate immune responses against microsporidia but can also serve as vessels for the dissemination of infection in the immunocompromised host; therefore, primary human macrophages were analyzed for altered gene expression of TLR in response to Encephalitozoon spp. MDM were incubated with spores for 6 h, and the total RNA was collected. The gene expression of TLR2, TLR4, and TNF-α (a known product of parasite challenge) was assessed using RT-qPCR. While the parasite challenge caused the predicted increase in TNF-α expression (Fig. 2A), an approximately twofold increase in TLR2 mRNA levels was also observed (Fig. 2B). Similar induction levels of TLR2 were observed for both E. cuniculi and E. intestinalis. Interestingly, TLR4 gene expression was not significantly augmented (Fig. 2C). These results, along with the TLR2 transfection studies, strongly suggest that the infectious spores can induce responses to increase the level of host receptor required for their recognition.

FIG. 2.

Microsporidia induce increased gene expression of TLR2 but not TLR4 in primary human macrophages. Total RNA was extracted from MDM cultures after challenge with spores for 6 h, and the gene expression of TLR2, TLR4, and TNF-α was measured by RT-qPCR. Data represent the means of results of six (TLR2, TLR4) and three (TNF-α) experiments. *, P ≤ 0.05.

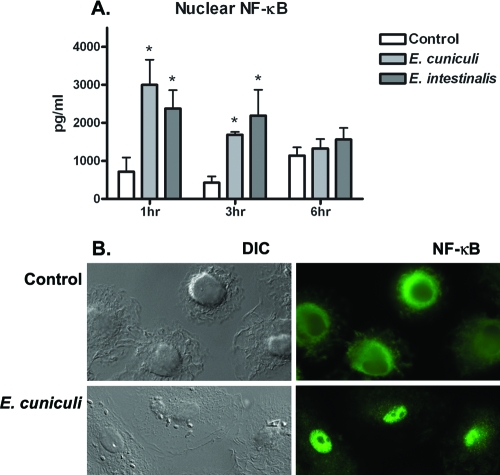

NF-κB translocation is activated in macrophages challenged with spores.

Little is understood about signaling events in response to microsporidian infections. Since many proinflammatory cytokines are at least under the partial regulation of the transcription activator NF-κB, our HEK studies and previously published reports of TNF-α suggest that NF-κB is activated during these infections. We next investigated whether Encephalitozoon spores could induce the translocation of NF-κBp65 into the nuclear compartment of primary human macrophages. Nuclear extracts were collected from cells at with spores 1, 3, and 6 h postchallenge and measured for total NF-κBp65. The translocation of NF-κBp65 was detected as early as 1 h postchallenge and continued to decrease at 3 and 6 h (Fig. 3A). To confirm the nuclear localization of NF-κBp65 in macrophages, immunostaining was performed on cells after the challenge with spores from both species. Again, NF-κBp65 was observed in the nucleus optimally at 1 h (Fig. 3B) and continued to decline up to 6 h.

FIG. 3.

The nuclear translocation of NF-κBp65 in primary human macrophages is initiated early after challenge with spores of Encephalitozoon spp. MDM cultures in six-well plates were challenged with spores for 1, 3, or 6 h. Nuclear proteins were collected and analyzed for levels of the NF-κBp65 subunit by ELISA. (A) Significant levels were observed at both 1 and 3 h postchallenge, while levels returned to that of the control after 6 h (n = 4). (B) To confirm NF-κBp65 activity, some MDM cultures were plated on cover glass and immunostained for nuclear localization. Nuclear NF-κB (green) was clearly observed after 1 h in the nucleus but not 6 h postchallenge. *, P ≤ 0.05.

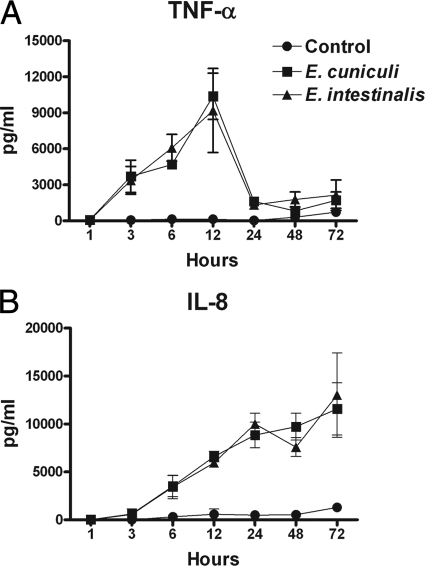

Encephalitozoon spp. induce the production of proinflammatory cytokines in primary human macrophages.

To substantiate the role of macrophages in the recognition of encephalitozoons in inducing inflammatory responses, the temporal expression of two inflammatory mediators, TNF-α and IL-8, was established. TNF-α and IL-8 are key inflammatory cytokines/chemokines that are produced in response to numerous types of intracellular pathogens. TNF-α and IL-8 were measured in supernatants from MDM cultures challenged with spores at various time points. Both species of microsporidia induced a strong, significant TNF-α response by 3 h postchallenge which peaked at 12 h and sharply fell after 24 h (Fig. 4A). In contrast, the production of IL-8 increased significantly by 6 h postchallenge and continued to increase over time up to 72 h (Fig. 4B).

FIG. 4.

Microsporidia induce the production of TNF-α and IL-8 by primary human macrophages. MDM cultures in 96-well plates were challenged with spores and stopped at various times by collecting the supernatants. TNF-α (A) and IL-8 (B) levels in supernatants were determined by ELISA. Data represent the means of results of six (TNF-α) and three (IL-8) experiments. For results at time points of 3, 6, 12, and 24 h for TNF-α and 6, 12, 24, 48, and 72 h for IL-8, the P value was ≤0.05.

Encephalitozoon-induced NF-κB translocation in macrophages is required for the production of TNF-α and IL-8.

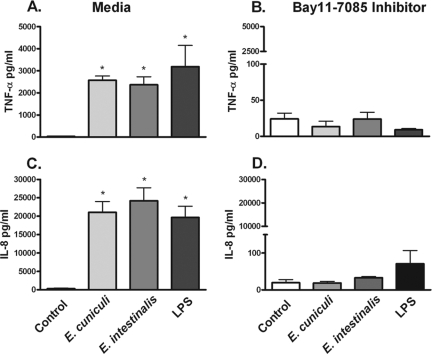

To establish the role of NF-κB in the production of the inflammatory mediators TNF-α and IL-8 in response to Encephalitozoon spores, the NF-κB inhibitor, Bay11-7085, was added to MDM cultures for 1 h prior to the challenge with microsporidian spores. This inhibitor is known to prevent the phosphorylation and degradation of IκB, thus preventing the nuclear translocation of NF-κB (34). A significant reduction in both TNF-α and IL-8 levels at 12 h was observed in cultures treated with Bay11-7085 (Fig. 5A to D). As anticipated, NF-κB activation is required for producing an effective inflammatory response against the parasites.

FIG. 5.

Blocking NF-κB activity prevents the production of microsporidian-induced TNF-α and IL-8 from primary human macrophages challenged with spores. Cultures of MDM in 96-well plates were preincubated for 60 min with 20 μM of the NF-κB inhibitor, Bay11-7085, followed by a 12-h challenge with Encephalitozoon spores or LPS (10 ng/ml). The levels of TNF-α and IL-8 were measured by ELISA. TNF-α (A and B) and IL-8 (C and D) were abrogated in cultures of both MDM in comparison to cultures without the addition of the inhibitor (n = 3). *, P ≤ 0.05.

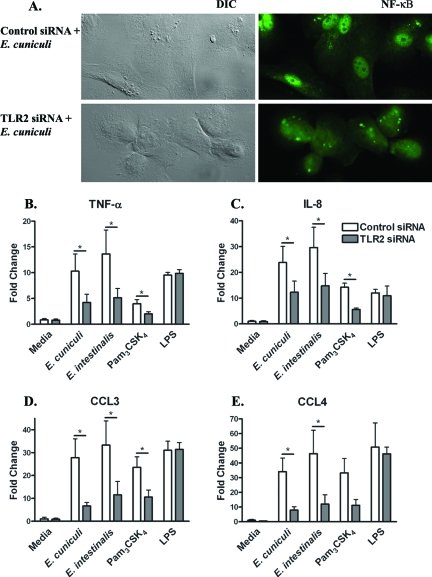

TLR2 knockdown in macrophages inhibits NF-κB nuclear translocation and subsequent cytokine and chemokine responses against microsporidia.

To directly show that the engagement of TLR2 by Encephalitozoon spp. in primary human macrophages results in NF-κB translocation and the production of inflammatory mediators, MDM were transfected with either control or TLR2 siRNA. Treatment with siRNA inhibits TLR2 mRNA expression, which could not be detected by RT-qPCR. TLR2 siRNA altered NF-κBp65 translocation, which was observed in control cells after a 1-h challenge with E. cuniculi but not in TLR2 siRNA-treated cells (Fig. 6A). After a 12-h challenge with the parasites, cell culture supernatants were collected and measured for the levels of TNF-α and IL-8 mediators as well as two NF-κB-driven chemokines, CCL3 and CCL4, previously described as being produced in response to Encephalitozoon challenge (12). The knockdown of TLR2 resulted in an approximately twofold decline in the production of TNF-α (Fig. 6B) and IL-8 (Fig. 6C) in comparison to control siRNA-transfected MDM when challenged with either species of the parasite. A reduction was also observed in siRNA TLR2-transfected MDM stimulated with the TLR2 agonist Pam3CSK4, whereas the siRNA knockdown had no effect on the cytokine response to the TLR4 agonist LPS. Similar results were also observed in supernatants analyzed for levels of CCL3 (Fig. 6D) and CCL4 (Fig. 6E). The levels of both chemokines were decreased in TLR2-transfected MDM compared to those of control transfections. Taken together, the data show a direct increase in these four inflammatory mediators as a result of Encephalitozoon ligation of TLR2 and subsequent NF-κB activation in primary human macrophages.

FIG. 6.

siRNA gene silencing of TLR2-reduced, Encephalitozoon-mediated NF-κB nuclear translocation and inflammatory responses. MDM transfected with TLR2 siRNA were challenged with Encephalitozoon spores, LPS (10 ng/ml), or Pam3CSK4 (50 ng/ml) for 12 h. Cells on coverslips were analyzed by immunofluorescence microscopy for nuclear NF-κB (A), and culture supernatants were analyzed by ELISA for the production of TNF-α (B), IL-8 (C), CCL3 (D), and CCL4 (E) inflammatory mediators. For the Encephalitozoon challenge, data represent the means of results of nine (TNF-α, IL-8) and five (CCL3, CCL4) experiments. *, P ≤ 0.05. DIC, differential interference contrast.

DISCUSSION

Encephalitozoon spp. have been recognized as emerging pathogens; however, very little information about the immunobiology of microsporidiosis in humans is available.

Pathology and epidemiological reports have identified immune effector cells at sites of infection (32) and detected increased levels of serum antibodies for microsporidia in humans (17, 39). Recent in vitro studies have shown that infections lead to the production of numerous cytokines and chemokines, including TNF-α, CCL2, CCL3, and CCL4 (12, 14). Although these responses have been well documented, to date, no known receptor involved in microsporidian recognition and signaling has been identified.

TLR have been shown to mediate the responses of many host-pathogen interactions. This family of receptors was first identified in Drosophila Toll mutants that succumbed to fungal infections, and soon after, their receptor homologues were identified in mammals (25, 26, 35, 37). Many insects, including Drosophila melanogaster, are natural hosts for entomogenous microsporidia (1). Given these receptors' involvement in inducing innate immune mechanisms leading to inflammatory responses, such as those previously reported against microsporidia, and their presence in all major natural hosts for microsporidia, TLR were investigated for their role in host recognition of Encephalitozoon spp. We report here that Encephalitozoon cuniculi and Encephalitozoon intestinalis are recognized by TLR2. Furthermore, the TLR2-parasite interaction mediates the nuclear translocation of NF-κB, which initiates the production of inflammatory mediators, such as TNF-α, IL-8, CCL3, and CCL4.

Although the cytokine and chemokine responses to Encephalitozoon infection have been described in previous studies, intracellular signaling molecules involved in the induction of this cascade, such as NF-κB, have not been reported. Similarly to others (14), we found that both species of Encephalitozoon elicit a very strong inflammatory response when introduced into primary human macrophages, and here we show that this interaction results in a rapid nuclear translocation of NF-κB (Fig. 3) and robust TNF-α and IL-8 production (Fig. 4) that can be inhibited by blocking IκB phosphorylation (Fig. 5). Interestingly, our temporal studies reveal that NF-κB translocation begins as early as 1 h postchallenge but continuously decreases thereafter and returns to control levels by 6 h (Fig. 3). The decrease in nuclear NF-κB is reflected in our TNF-α data, which show increases in secreted protein levels to 12 h followed by a sharp decrease at 24 h (Fig. 4). Increases in TNF-α mRNA at 6 h postchallenge (Fig. 2) followed by declining levels over time (data not shown) were also observed. Unlike those of the TNF-α response, IL-8 protein levels (Fig. 4) continue to increase over time up to 72 h postchallenge, regardless of the level of nuclear NF-κB. However, the initial production of IL-8 is altogether abrogated when NF-κB translocation is blocked (Fig. 5). Similarly, Mpiga et al. showed that IL-8 expression was sustained but that TNF-α levels peaked and decreased in cultures infected with Chlamydia trachomatis (27). Control of IL-8 expression has been shown to be regulated by several signaling pathways and transcriptional regulators, including but not limited to NF-κB. Additional pathways may be required for the stabilization of IL-8 mRNA, allowing for sustained levels of IL-8 expression (19). Taken together, our studies illustrate a mechanism involving the nuclear translocation of NF-κB which initiates an immediate inflammatory response against the parasite but requires a second mechanism to sustain the levels of IL-8. This mechanism may be used to prevent an overreaction of the inflammatory response but continues to produce a potent chemokine that will attract additional cells for pathogenic clearance.

These studies show that TLR are involved in the recognition of Encephalitozoon spores, not only in classically transfected cell lines but also in primary cells. Studies using transfected HEK293 cells showed that TLR2 alone was sufficient to induce IL-8 production but that TLR4 alone or TLR4 in collaboration with the accessory molecules MD2 and CD14 was not (Fig. 1). Additionally, heat-inactivated E. cuniculi stimulated a TLR2-mediated response observed at lower levels than that observed with viable spores. This may simply be attributed to the method of parasite inactivation which may cause molecular alterations to the spore coat that lessen the ability of TLR2 recognition. Similar differential cytokine responses were observed between viable and heat-inactivated Candida albicans organisms, and so it was suggested that an increased temperature may manipulate structural moieties found on the yeast surface that influence receptor recognition and responses (15, 29). Alternatively, it may indicate that the pathogen-associated molecular pattern is located on a parasite surface which is exposed only during or after leaving the exospore. This observation predicts that the spores would have to be viable to trigger the TLR2 pathways.

Macrophages are professional antigen-presenting cells found at mucosal barriers and are equipped with TLR to recognize a variety of pathogens (20). To provide evidence for the direct role of TLR in the recognition of Encephalitozoon spp., siRNA was utilized to knock down the expression of TLR2 in primary human macrophages. Our results indicate that NF-κBp65 nuclear translocation is inhibited and that TNF-α and IL-8 production is reduced by almost 50% in knockdown cultures stimulated with either species of microsporidia (Fig. 6). In addition, a reduction in the chemokines CCL3 and CCL4 was also observed in these cultures. Although we observed decreases in TNF-α, IL-8, CCL3, and CCL4, the production of these inflammatory mediators were not completely abrogated via our siRNA model, and thus, it remains possible that the pathogens can be recognized by additional receptors that have not been described in this study. Our data clearly show that TLR2 serves as a major receptor for host recognition of Encephalitozoon spores. The lack of response by the TLR4 HEK transfectants and a clear suppression of the proinflammatory mediators confirm that these responses are TLR2 specific.

Although no specific agonists from microsporidian spore coats or sporoplasms have been defined for TLR recognition, molecules from the exospore, endospore, polar filament, and sporoplasm are rapidly being identified; some of these have a striking resemblance to molecules from other microorganisms that are TLR agonists. Cell wall components of fungi, such as zymosan and β-glucan, have proven to be potent stimulants of inflammatory responses by signaling through TLR. Recently, linear O-linked mannosylated glycans derived from the spore coat in E. cuniculi were described (38) These microsporidian glycans closely resemble molecules found on the surface of C. albicans that trigger TLR activation (29). Additionally, proteins identified in the endospore are believed to be attached to the membrane by GPI anchors. GPI anchors derived from Trypanosoma cruzi and Toxoplasma gondii have been identified in stimulating TLR2 (3, 7). This innate recognition has been portrayed as one way that our defenses can identify self from nonself and begins an immediate response that will result in pathogenic clearance. It has also been described as a mechanism of immune evasion for pathogens (30).

Our presented data show that the opportunistic pathogens of Encephalitozoon spp. induce TLR2 signaling, which leads to the immediate nuclear translocation of NF-κB and the subsequent production and secretion of TNF-α and IL-8 inflammatory mediators. These studies have also raised further questions about additional unidentified receptors potentially involved in microsporidian recognition and/or signaling molecules involved in immunosuppression, which will be addressed in future studies. Defining the host-parasite interaction at the molecular level is helpful in understanding the pathology of the disease and developing possible methods of treatment and prevention.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grant RR020159-01, by Louisiana Board of Regents grant LEQSF (2004-7)-RD-A-10, and by LSU FRG.

We thank Elizabeth Didier and Lisa Bowers for donating the E. cuniculi III strain and the staff at Our Lady of the Lake Blood Center for providing the buffy coats. We also thank Karin Peterson and John Larkin for their critical review of the manuscript and Andrew Whitehead and Jen Roach for their technical expertise. We acknowledge the contributions of our undergraduate researchers: Anne Hotard, Tyler DeBleuix, and Aryaz Sheybani.

Editor: W. A. Petri, Jr.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 4 August 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Becnel, J. J., and T. G. Andreadis. 1999. Microsporidia in insects, p. 447-501. In M. Wittner and L. M. Weiss (ed.), The microsporidia and microsporidiosis. ASM Press, Washington, DC.

- 2.Bigliardi, E., and L. Sacchi. 2001. Cell biology and invasion of the microsporidia. Microbes Infect. 3373-379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Campos, M. A., I. C. Almeida, O. Takeuchi, S. Akira, E. P. Valente, D. O. Procopio, L. R. Travassos, J. A. Smith, D. T. Golenbock, and R. T. Gazzinelli. 2001. Activation of Toll-like receptor-2 by glycosylphosphatidylinositol anchors from a protozoan parasite. J. Immunol. 167416-423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carlson, J. R., L. Li, C. L. Helton, R. J. Munn, K. Wasson, R. V. Perez, B. J. Gallay, and W. E. Finkbeiner. 2004. Disseminated microsporidiosis in a pancreas/kidney transplant recipient. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 12841-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen, X.-M., S. P. O'Hara, J. B. Nelson, P. L. Splinter, A. J. Small, P. S. Tietz, A. H. Limper, and N. F. LaRusso. 2005. Multiple TLRs are expressed in human cholangiocytes and mediate host epithelial defense responses to Cryptosporidium parvum via activation of NF-κB. J. Immunol. 1757447-7456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Collart, M. A., P. Baeuerle, and P. Vassalli. 1990. Regulation of tumor necrosis factor alpha transcription in macrophages: involvement of four κB-like motifs and of constitutive and inducible forms of NF-κB. Mol. Cell. Biol. 101498-1506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Debierre-Grockiego, F., M. A. Campos, N. Azzouz, J. Schmidt, U. Bieker, M. G. Resende, D. S. Mansur, R. Weingart, R. R. Schmidt, D. T. Golenbock, R. T. Gazzinelli, and R. T. Schwarz. 2007. Activation of TLR2 and TLR4 by glycosylphosphatidylinositols derived from Toxoplasma gondii. J. Immunol. 1791129-1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Didier, E. S. 2005. Microsporidiosis: an emerging and opportunistic infection in humans and animals. Acta Trop. 9461-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Didier, E. S., P. J. Didier, D. N. Friedberg, S. M. Stenson, J. M. Orenstein, R. W. Yee, F. O. Tio, R. M. Davis, C. Vossbrinck, N. Millichamp, et al. 1991. Isolation and characterization of a new human microsporidian, Encephalitozoon hellem (n. sp.), from three AIDS patients with keratoconjunctivitis. J. Infect. Dis. 163617-621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Didier, E. S., M. E. Stovall, L. C. Green, P. J. Brindley, K. Sestak, and P. J. Didier. 2004. Epidemiology of microsporidiosis: sources and modes of transmission. Vet. Parasitol. 126145-166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fischer, J., D. Tran, R. Juneau, and H. Hale-Donze. 2008. Kinetics of Encephalitozoon spp. infection of human macrophages. J. Parasitol. 94169-175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fischer, J., J. West, N. Agochukwu, C. Suire, and H. Hale-Donze. 2007. Induction of host chemotactic response by Encephalitozoon spp. Infect. Immun. 751619-1625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Franzen, C. 2005. How do microsporidia invade cells? Folia Parasitol. (Praha) 5236-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Franzen, C., P. Hartmann, and B. Salzberger. 2005. Cytokine and nitric oxide responses of monocyte-derived human macrophages to microsporidian spores. Exp. Parasitol. 1091-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gantner, B. N., R. M. Simmons, and D. M. Underhill. 2005. Dectin-1 mediates macrophage recognition of Candida albicans yeast but not filaments. EMBO J. 241277-1286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gill, E. E., and N. M. Fast. 2006. Assessing the microsporidia-fungi relationship: combined phylogenetic analysis of eight genes. Gene 375103-109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Halanova, M., L. Cislakova, A. Valencakova, P. Balent, J. Adam, and M. Travnicek. 2003. Serological screening of occurrence of antibodies to Encephalitozoon cuniculi in humans and animals in Eastern Slovakia. Ann. Agric. Environ. Med. 10117-120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hale-Donze, H., and E. Didier. July 2007. Microsporidioses. In Encyclopedia of life sciences. John Wiley & Sons Ltd., Chichester, England. http://www.els.net/[doi: 10.1002/9780470015902.a0001930]. [DOI]

- 19.Hoffmann, E., O. Dittrich-Breiholz, H. Holtmann, and M. Kracht. 2002. Multiple control of interleukin-8 gene expression. J. Leukoc. Biol. 72847-855. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Janeway, C., P. Travers, M. Walport, and M. Shlomchik. 2005. Immunobiology: the immune system in health and disease, 6th ed. Garland Science, New York, NY.

- 21.Khaleduzzaman, M., J. Francis, M. E. Corbin, E. McIlwain, M. Boudreaux, M. Du, T. W. Morgan, and K. E. Peterson. 2007. Infection of cardiomyocytes and induction of left ventricle dysfunction by neurovirulent polytropic murine retrovirus. J. Virol. 8112307-12315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kunsch, C., and C. A. Rosen. 1993. NF-κB subunit-specific regulation of the interleukin-8 promoter. Mol. Cell. Biol. 136137-6146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee, M. S., and Y. J. Kim. 2007. Signaling pathways downstream of pattern-recognition receptors and their cross talk. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 76447-480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leelayoova, S., I. Subrungruang, R. Rangsin, P. Chavalitshewinkoon-Petmitr, J. Worapong, T. Naaglor, and M. Mungthin. 2005. Transmission of Enterocytozoon bieneusi genotype a in a Thai orphanage. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 73104-107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lemaitre, B., E. Nicolas, L. Michaut, J. M. Reichhart, and J. A. Hoffmann. 1996. The dorsoventral regulatory gene cassette spätzle/Toll/cactus controls the potent antifungal response in Drosophila adults. Cell 86973-983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Medzhitov, R. 2001. Toll-like receptors and innate immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 1135-145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mpiga, P., S. Mansour, R. Morisset, R. Beaulieu, and M. Ravaoarinoro. 2006. Sustained interleukin-6 and interleukin-8 expression following infection with Chlamydia trachomatis serovar L2 in a HeLa/THP-1 cell co-culture model. Scand. J. Immunol. 63199-207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Netea, M. G., G. Ferwerda, C. A. van der Graaf, J. W. Van der Meer, and B. J. Kullberg. 2006. Recognition of fungal pathogens by toll-like receptors. Curr. Pharm. Des. 124195-4201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Netea, M. G., N. A. Gow, C. A. Munro, S. Bates, C. Collins, G. Ferwerda, R. P. Hobson, G. Bertram, H. B. Hughes, T. Jansen, L. Jacobs, E. T. Buurman, K. Gijzen, D. L. Williams, R. Torensma, A. McKinnon, D. M. MacCallum, F. C. Odds, J. W. Van der Meer, A. J. Brown, and B. J. Kullberg. 2006. Immune sensing of Candida albicans requires cooperative recognition of mannans and glucans by lectin and Toll-like receptors. J. Clin. Investig. 1161642-1650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Netea, M. G., J. W. M. Van der Meer, R. P. Sutmuller, G. J. Adema, and B.-J. Kullberg. 2005. From the Th1/Th2 paradigm towards a Toll-like receptor/T-helper bias. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 493991-3996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nkinin, S. W., T. Asonganyi, E. S. Didier, and E. S. Kaneshiro. 2007. Microsporidian infection is prevalent in healthy people in Cameroon. J. Clin. Microbiol. 452841-2846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Orenstein, J. M. 2003. Diagnostic pathology of microsporidiosis. Ultrastruct. Pathol. 27141-149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Peuvel-Fanget, I., V. Polonais, D. Brosson, C. Texier, L. Kuhn, P. Peyret, C. Vivares, and F. Delbac. 2006. EnP1 and EnP2, two proteins associated with the Encephalitozoon cuniculi endospore, the chitin-rich inner layer of the microsporidian spore wall. Int. J. Parasitol. 36309-318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pierce, J. W., R. Schoenleber, G. Jesmok, J. Best, S. A. Moore, T. Collins, and M. E. Gerritsen. 1997. Novel inhibitors of cytokine-induced IκBα phosphorylation and endothelial cell adhesion molecule expression show anti-inflammatory effects in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 27221096-21103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rock, F. L., G. Hardiman, J. C. Timans, R. A. Kastelein, and J. F. Bazan. 1998. A family of human receptors structurally related to Drosophila Toll. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95588-593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schottelius, J., and S. C. da Costa. 2000. Microsporidia and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 95(Suppl. 1)133-139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Takeda, K., and S. Akira. 2005. Toll-like receptors in innate immunity. Int. Immunol. 171-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Taupin, V., E. Garenaux, M. Mazet, E. Maes, H. Denise, G. Prensier, C. P. Vivares, Y. Guerardel, and G. Metenier. 2007. Major O-glycans in the spores of two microsporidian parasites are represented by unbranched manno-oligosaccharides containing alpha-1,2 linkages. Glycobiology 1756-67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.van Gool, T., C. Biderre, F. Delbac, E. Wentink-Bonnema, R. Peek, and C. P. Vivares. 2004. Serodiagnostic studies in an immunocompetent individual infected with Encephalitozoon cuniculi. J. Infect. Dis. 1892243-2249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang, J. P., E. A. Kurt-Jones, O. S. Shin, M. D. Manchak, M. J. Levin, and R. W. Finberg. 2005. Varicella-zoster virus activates inflammatory cytokines in human monocytes and macrophages via Toll-like receptor 2. J. Virol. 7912658-12666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Xu, Y., P. Takvorian, A. Cali, F. Wang, H. Zhang, G. Orr, and L. M. Weiss. 2006. Identification of a new spore wall protein from Encephalitozoon cuniculi. Infect. Immun. 74239-247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xu, Y., and L. M. Weiss. 2005. The microsporidian polar tube: a highly specialised invasion organelle. Int. J. Parasitol. 35941-953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]