Abstract

Cryptococcus neoformans is an opportunistic fungal pathogen that primarily causes disease in immunocompromised individuals. Dendritic cells (DCs) can phagocytose C. neoformans, present cryptococcal antigen, and kill C. neoformans. However, early events following C. neoformans phagocytosis by DCs are not well defined. We hypothesized that C. neoformans traffics to the endosome and the lysosome following phagocytosis by DCs and is eventually killed in the lysosome. Murine bone marrow-derived DCs (BMDCs) or human monocyte-derived DCs (HDCs) were incubated with live, encapsulated C. neoformans yeast cells and opsonizing antibody. Following incubation, DCs were intracellularly stained with antibodies against EEA1 (endosome) and LAMP-1 (late endosome/lysosome). As assessed by confocal microscopy, C. neoformans trafficked to endosomal compartments of DCs within 10 min and to lysosomal compartments within 30 min postincubation. For HDCs, the studies were repeated using complement-sufficient autologous plasma for the opsonization of C. neoformans. These data showed results similar to those for antibody opsonization, with C. neoformans localized to endosomes within 20 min and to lysosomes within 60 min postincubation. Additionally, the results of live real-time imaging studies demonstrated that C. neoformans entered lysosomal compartments within 20 min following the initiation of phagocytosis. The results of scanning and transmission electron microscopy demonstrated conventional zipper phagocytosis of C. neoformans by DCs. Finally, lysosomal extracts were purified from BMDCs and incubated with C. neoformans to determine their potential to kill C. neoformans. The extracts killed C. neoformans in a dose-dependent manner. This study shows that C. neoformans enters into endosomal and lysosomal pathways following DC phagocytosis and can be killed by lysosomal components.

Cryptococcus neoformans is an opportunistic fungal pathogen that causes disease predominantly in immunocompromised patients, particularly individuals with AIDS, transplant recipients, and those with lymphoid and hematological malignancies (25, 35, 47, 49). Protective immunity to C. neoformans is dependent on an adaptive Th1-type immune response (18-21, 36, 37). Dendritic cells (DCs) are important in the presentation of foreign antigens to T cells in the lymphoid tissues and the initiation of an adaptive immune response against these antigens (3, 34, 48, 56). The results of previous studies by our laboratory have shown that DCs have the capacity to phagocytose C. neoformans in vitro by a process which requires opsonization with either complement or antibody (22). Following phagocytosis, DCs are capable of antifungal activity against C. neoformans (22). In addition, we have shown that C. neoformans can be phagocytosed by DCs in vivo following pulmonary inoculation (59), which leads to DC maturation and antigen presentation to Cryptococcus-specific T cells.

Phagocytosis of infectious organisms begins with binding of the organism to the cell, formation of an endocytic vesicle (phagosome), maturation of the phagosome into a phagolysosome, and eventual digestion within the phagosome (reviewed in reference 52). DCs phagocytose organisms and process them via the endocytic pathway for presentation by major histocompatibility complex class II (MHC-II) (41, 53). The maturation of the endocytic compartment is dependent on fusion to the late endosome or lysosome, and once phagocytosed cargo reaches the lysosome, a combination of reactive oxygen and nitrogen intermediates, acidic pH, and cathepsin hydrolytic enzyme activities can contribute to killing, degradation, and proteolysis (9, 12, 32, 53, 54, 55). In addition, endosomes and lysosomes function as storage and antigen-loading compartments for MHC-II (16, 31). Following the degradation of phagocytosed microbial pathogens, microbial antigens can be targeted to the MHC-II pathway for presentation to T cells (4, 23, 34, 60).

As mentioned earlier, one consequence of lysosomal entry is that enzymatic action can kill phagocytosed organisms. For the fungus Histoplasma capsulatum, phagolysosomal fusion can lead to the killing and degradation of phagocytosed organisms by DCs (17). DC killing of fungal pathogens can proceed by oxidative and/or nonoxidative mechanisms. Thus, human DCs (HDCs) can kill phagocytosed Candida albicans in the absence of superoxide or nitric oxide (38), while mouse DCs kill C. albicans yeasts following recognition by the mannose-fucose receptor and the release of nitric oxide and inducible nitric oxide synthase (14).

Following phagocytosis of C. neoformans by murine DCs, the fungus has been shown to colocalize with CD63-positive compartments (2). CD63, also known as LAMP-3, is a tetraspanin that is also a marker of endosomes and lysosomes. CD63 interacts with MHC-II during antigen presentation and may chaperone MHC-II through the endosomal pathway and be involved in the recycling of MHC-II (43, 58). However, the entry into early endosomes of DCs and DC lysosomal degradation of C. neoformans have not been explored. We hypothesized that following phagocytosis by DCs, C. neoformans enters the endosomal/lysosomal pathway, where it is killed and degraded for antigen presentation to T cells. Therefore, in the present studies, we determined the intracellular location of C. neoformans organisms following phagocytosis by murine DCs and HDCs. Moreover, we examined the capacity of lysosomes isolated from DCs to kill C. neoformans.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents.

Unless otherwise stated, chemical reagents of the highest quality available were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich Co. (St. Louis, MO), tissue culture media were purchased from Gibco Life Technologies (Rockville, MD), and plasticware was purchased from Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA). The medium used in murine bone marrow-derived DC (BMDC) experiments was RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum, 2 mM l-glutamine, 100 U penicillin/ml, 100 μg of streptomycin/ml, and 50 mM 2-mercaptoethanol (complete medium). The medium used in HDC experiments was RPMI 1640 supplemented with 5% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum, 2 mM l-glutamine, 100 U penicillin/ml, 100 μg of streptomycin/ml, 50 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, and 10 mM HEPES (HDC medium). All cell culture incubations were performed at 37°C in a humidified environment supplemented with 5% CO2.

Culture of Cryptococcus.

Cryptococcus neoformans serotype A encapsulated strain 145 (ATCC 62070; American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA) was cultured for 24 h at 30°C in yeast extract-peptone-dextrose plus 2% glucose. Live C. neoformans organisms were washed with sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), counted, and resuspended in sterile PBS to the concentration needed for each experiment.

Fluorescent labeling of Cryptococcus.

Live C. neoformans organisms were washed with sterile 0.1 M sodium bicarbonate buffer, pH 8.0 (staining buffer), counted, and resuspended to 5 × 108/ml. C. neoformans yeast was incubated with 2 μg/ml Oregon green 488 (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) at room temperature in the dark for 1 h. The organisms were then washed three times with sterile PBS, counted, and resuspended in sterile PBS to the concentration needed for each experiment.

Fluorescent labeling of 3C2 antibody.

Opsonizing anti-capsular monoclonal 3C2 antibody (gift of Thomas Kozel, University of Nevada, Reno, NV) (50) was diluted in staining buffer to 100 μg/ml. Oregon green 488 was added at 100 μg/ml, and the mixture was incubated at room temperature in the dark for 1 h. The antibody was separated from excess dye by using a Sephadex G-25 column.

BMDCs.

C57BL/6 mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME) and were housed under pathogen-free conditions in microisolator cages according to institutionally recommended guidelines at the University of Massachusetts Medical School Department of Animal Medicine. BMDC culture was performed as previously described (22, 30). Briefly, bone marrow was flushed from the femurs and tibiae of C57BL/6 mice. Cells were washed, counted, and plated in complete medium supplemented with 10% filter-sterilized supernatant from the J558L cell line (which constitutively produces granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor) (39). One half of the medium was replaced every three days, and the cells were harvested on day 8 or 9 following plating. The cells were then purified by positive selection using magnetically labeled CD11c antibodies (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA).

HDCs.

Monocyte-derived HDCs were obtained as described previously (44). Briefly, peripheral blood was obtained from healthy volunteers by venipuncture following informed consent, using a protocol approved by the University of Massachusetts Medical School Institutional Review Board. The blood was anticoagulated with heparin (American Pharmaceutical Partners, Inc., Los Angeles, CA) and diluted 1:1 with Hank's balanced salt solution (BioWhittaker, Walkersville, MD). Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were purified in a Leukosep tube (Greiner Bio-One, Germany) over a Lymphoprep gradient (Accurate Chemical & Scientific Corp., Westbury, NY). The tubes were centrifuged at 1,000 × g for 10 min without the brake. After separation, the autologous diluted plasma was collected and stored at −20°C until use. The PBMC layer was isolated and washed three times with HDC medium. PBMCs (1 × 105 to 3 × 105/well) were added to a six-well tissue culture plate for 2 h at 37°C to allow monocyte adherence and then gently washed to remove nonadherent cells. HDCs were cultured for 7 days with 50 ng/ml recombinant human interleukin-4 (Peprotech, Rocky Hill, NJ) and 150 ng/ml recombinant human granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (sargramostim; Bayer, Wayne, NJ). The cells were then positively selected for CD1c (BDCA-1) expression by using magnetically labeled CD1c antibodies (Miltenyi Biotec).

DC phagocytosis of C. neoformans.

BMDCs or HDCs were harvested, purified, and counted. DCs and C. neoformans organisms were incubated at a 2:1 ratio in the presence of 1 μg/ml of Oregon green-stained 3C2 opsonizing antibody for 10, 20, 30, or 60 min at 37°C in 1.7-ml microcentrifuge tubes (Costar, Corning, NY). For phagocytosis with plasma opsonins, HDCs were incubated with Oregon green-labeled Cryptococcus in the presence of autologous human plasma.

Intracellular staining.

Following incubation of DCs and C. neoformans organisms, DCs were fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 10 min at room temperature. After fixation, the cells were washed and permeabilized with 0.1% saponin for 10 min at room temperature. While permeabilized, the cells were intracellularly stained with either anti-EEA1 (ABR Affinity Bioreagents, Golden, CO) or anti-LAMP-1 (mouse; eBioscience, San Diego, CA, or human; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA). For both BMDCs and HDCs, purified anti-EEA1 was the primary antibody and was followed by anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG) conjugated to Alexa 568 (Molecular Probes). For BMDCs, biotinylated LAMP-1 was used, followed by streptavidin-Alexa 568 (Molecular Probes). For HDCs, purified LAMP-1 was the primary antibody and was followed by anti-rabbit IgG conjugated to Alexa 568 (Molecular Probes). Control antibodies matched for species and isotype were used for each experiment as follows: for EEA1, rabbit IgG (Sigma); for human LAMP-1, mouse IgG1 (eBioscience); and for murine LAMP-1, rat IgG2a (eBioscience). Phagocytosis was defined as the detection of the presence of intracellular C. neoformans organisms by confocal microscopy. The intracellular location of the C. neoformans yeast cells was confirmed by z-stack images. Confocal imaging was performed on a Leica TCS SP2 inverted confocal microscope (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany), and Leica confocal software (LCS) was used for the acquisition of images. The images were viewed using a 63×, 1.40-numerical-aperture oil-immersion Leica lens and were digitally increased in size fourfold by using LCS. Fusion with endosomes or lysosomes was determined by the visualization of C. neoformans organisms within the stained compartments.

Live imaging of phagocytosis.

BMDCs were harvested, purified, and incubated with C. neoformans yeast cells at a 2:1 ratio in the presence of 1 μg/ml of Oregon green-labeled 3C2 antibody and 50 nM LysoTracker red (Molecular Probes). Samples were placed on ice until live imaging by confocal microscopy. For imaging, the sample was placed in a glass-bottomed, 35-mm culture dish (MatTek Corp., Ashland, MA) on a stage heated to 37°C. Once the interaction of DCs with C. neoformans was observed, confocal images were obtained every 30 s in order to determine whether entry of C. neoformans into the stained lysosomal compartment occurred.

Examination of phagocytosis by electron microscopy.

BMDCs were harvested, purified, and incubated with C. neoformans yeast cells at a 2:1 ratio in the presence of 1 μg/ml 3C2 opsonizing antibody for 10, 20, 30, 40, 50, or 60 min. Following incubation, cells were fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde and processed for transmission electron microscopy (TEM) or scanning electron microscopy (SEM). Following sample preparation, cells were examined on a Philips CM10 TEM for the presence of C. neoformans in intracellular compartments. For SEM, cells were examined on an FEI Quanta 200 FEG MKII SEM for the uptake of C. neoformans by DCs.

Lysosomal extract purification from DCs.

BMDCs were cultured, harvested, and purified as described above. Crude lysosomal extracts were obtained (S. L. Newman and W. Lemen, unpublished data). Briefly, 1× lysosomal extraction buffer (Sigma-Aldrich) was added at 2.7 ml per 3 × 108 cells. DCs were homogenized with a PowerGen 700 homogenizer (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA) using a 7- by 110-mm homogenizer tip (Fisher Scientific). The homogenizer was passed through the cells 20 to 25 times (which disrupted 75 to 80% of the cells), and then cells were centrifuged for 10 min at 1,000 × g to remove intact cells and cellular debris. The supernatants were collected and centrifuged for 20 min at 20,000 × g to pellet lysosomes. The supernatants were discarded, and the pellet containing the lysosomes was resuspended in 1 ml of 1× extraction buffer. The sample was then sonicated for 20 s at a setting of 40% on a model 500 Sonic Dismembrator (Fisher Scientific). The resultant product following sonication was the crude lysosomal extract.

Lysosomal killing of C. neoformans.

C. neoformans killing assays were performed as previously described (28, 33, 42). Briefly, following culture of encapsulated C. neoformans yeast cells, the organisms were washed three times with sterile PBS and resuspended in 10 mM phosphate buffer with 2% RPMI 1640, pH 5.5 (lysosomal buffer). The fungi were then added to 96-well plates in a volume of 50 μl (2.5 × 105/ml). Lysosomal extracts were added at 10, 25, and 50%, and the wells were filled with lysosomal buffer to a total volume of 100 μl. The plates were then incubated for 24 h at 37°C. Following incubation, the organisms were diluted in sterile PBS and plated on Sabouraud dextrose agar plates. The plates were incubated at room temperature for 3 days, and then CFU were counted.

Statistical analysis.

For statistical comparisons, we utilized one-way analysis of variance with Tukey's multiple correction test. P values of <0.05 were considered significant. The data were analyzed by using GraphPad Prism software (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA).

RESULTS

Intracellular trafficking of C. neoformans yeast following phagocytosis by DCs.

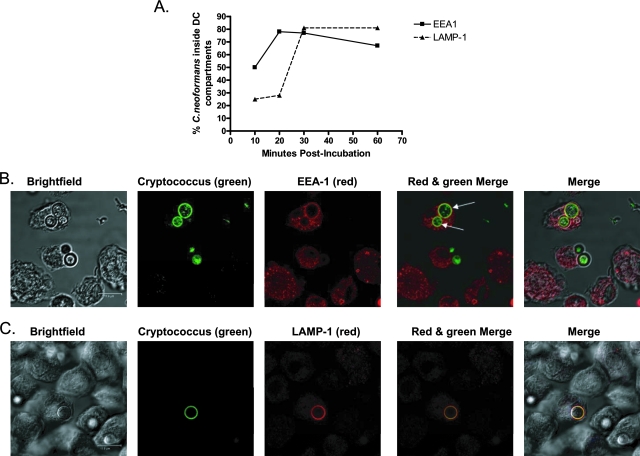

In order to determine the intracellular location of C. neoformans yeast cells following phagocytosis by DCs, BMDCs and HDCs were incubated with C. neoformans. The DCs were then fixed, intracellularly stained with antibodies for EEA1 (early endosomes) or LAMP-1 (late endosomes/lysosomes), and examined by confocal microscopy. The results showed that for both BMDCs and HDCs, more than half of the C. neoformans-containing phagosomes had fused with EEA1-positive compartments by 10 min postincubation (Fig. 1A). By 20 min postincubation, the majority of C. neoformans-containing phagosomes had fused with EEA1-positive compartments, and this remained constant through 60 min postincubation. LAMP-1-positive compartments fused with few C. neoformans-containing phagosomes at early time points, but the majority had fused by 30 min postincubation and continued to be fused through 60 min postincubation (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Localization of C. neoformans to early endosomes and lysosomes following phagocytosis by murine DCs. Murine DCs were purified and incubated with encapsulated C. neoformans cells and Oregon green 488-labeled opsonizing antibody. DCs were then fixed, permeabilized, and stained with anti-EEA1 antibody (Alexa 568) or anti-LAMP-1 antibody (Alexa 568). Cells were imaged by confocal microscopy. (A) Line graph of average percentages of C. neoformans organisms inside EEA1- and LAMP-1-positive compartments of DCs following phagocytosis at 10, 20, 30, and 60 min postincubation. Data shown are representative of the results of six to eight independent experiments performed with BMDCs and three independent experiments performed with HDCs. Three to four images (including z-stack images) were obtained for each time point. (B) Representative confocal images of C. neoformans organisms in EEA1-positive compartments at 20 min postincubation. The arrows (in the red and green merged image) point to the two C. neoformans organisms in EEA1-positive compartments. (C) Representative confocal images of C. neoformans organisms shown in LAMP-1-positive compartments at 60 min postincubation. Scale bar = 11.9 μm. In panels B and C, “Merge” panels at far right show merged images of bright-field, red, and green panels.

Live imaging of C. neoformans phagocytosis by DCs.

Although the data from the intracellular staining confirmed the entry of C. neoformans organisms into endosomes and lysosomes, those experiments were timed from the beginning of the incubation, not the beginning of phagocytosis. In order to determine how quickly entry into lysosomes occurred following contact and phagocytosis, live confocal imaging was performed. The results showed that the majority of C. neoformans organisms appeared to enter the lysosomal compartment of BMDCs (stained with LysoTracker red) within 20 min following uptake (Fig. 2; see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material).

FIG. 2.

Live imaging of DC phagocytosis of C. neoformans organisms and phagolysosomal fusion. Murine DCs were incubated with encapsulated C. neoformans cells, Oregon green 488-labeled opsonizing antibody, and LysoTracker red. Live cells were examined by confocal microscopy at 37°C, with the zero-minute time point indicative of when phagocytosis commenced. Images shown are representative of 10 observations of BMDCs phagocytosing C. neoformans cells. In 8 out of 10 of these observations, including the one shown in the figure, C. neoformans yeast was found in LysoTracker red-positive (lysosomal) compartments within 20 min following phagocytosis. Scale bar = 11.9 μm.

Cryptococcus trafficking following opsonization with complement-sufficient plasma.

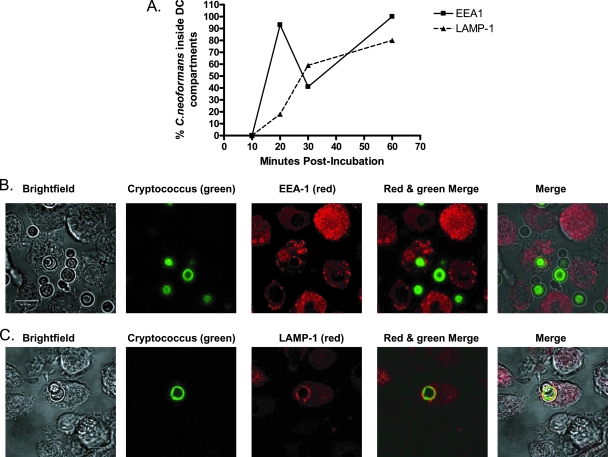

In natural human infections, anticryptococcal antibodies may be absent or complexed with shed capsule. In those situations, binding and phagocytosis are dependent upon complement opsonization (22, 26, 51). Phagocytosis by complement- and Ig-opsonized organisms proceeds by different receptors (complement receptors and Fc receptors, respectively) (4). Therefore, we next determined the intracellular fate of C. neoformans in DCs following opsonization with complement-sufficient autologous human plasma. HDCs were incubated with C. neoformans yeast and autologous plasma, and then the DCs were intracellularly stained with EEA1 or LAMP-1 and examined by confocal microscopy (Fig. 3). The results showed that the C. neoformans-containing phagosomes had fused with EEA1-positive compartments by 20 min postincubation and remained fused through 60 min postincubation. The majority of C. neoformans-containing phagosomes had fused with LAMP-1-positive compartments by 30 min postincubation and continued to be fused when observed at 60 min postincubation.

FIG. 3.

Localization of C. neoformans to early endosomes and lysosomes following serum opsonization and phagocytosis by HDCs. HDCs were incubated with encapsulated C. neoformans in the presence of complement-sufficient autologous plasma. Following incubation, HDCs were fixed, permeabilized, and stained with anti-EEA1 antibody (Alexa 568) or anti-LAMP-1 antibody (Alexa 568). (A) Line graph of average percentages of C. neoformans organisms inside EEA1- and LAMP-1-positive compartments of HDCs following phagocytosis at 10, 20, 30, and 60 min postincubation. These data are from three independent experiments. Three to four images (including z-stack images) were obtained at each time point. (B) Representative confocal images of C. neoformans organisms in EEA1-positive compartments at 20 min postincubation. (C) Representative confocal images of C. neoformans organisms in LAMP-1-positive compartments at 30 min postincubation. Scale bar = 11.9 μm. In panels B and C, “Merge” panels at far right show merged images of bright-field, red, and green panels.

Electron microscopy of internalized C. neoformans organisms in DCs.

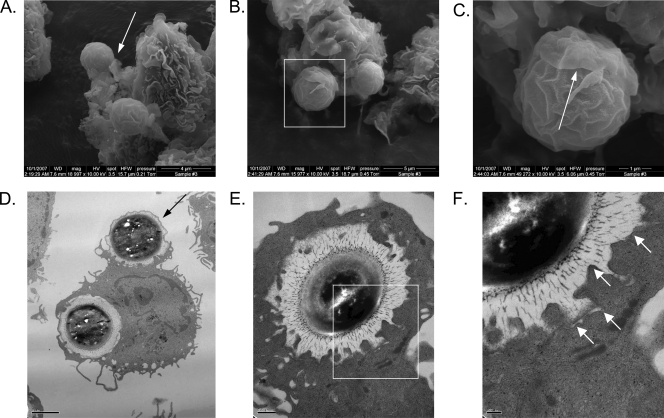

Phagocytosis of microorganisms by DCs can proceed by conventional (“zipper”) or “coiling” mechanisms (6-8, 14, 40). To determine how DC phagocytosis of C. neoformans proceeded and to confirm that C. neoformans was indeed found within intracellular compartments of the DCs, SEM and TEM were performed following the incubation of BMDCs with C. neoformans yeast (Fig. 4). By 10 min, the earliest time point examined, C. neoformans yeast cells were observed in the process of being internalized by conventional phagocytosis (Fig. 4A to D). Coiling phagocytosis was not observed. In addition, the TEM images demonstrated that fully phagocytosed C. neoformans organisms were surrounded by intact membranes that abutted the organisms' capsules (Fig. 4D to F).

FIG. 4.

Results of electron microscopy of C. neoformans phagocytosis by DCs. Following culture, BMDCs were purified and incubated for specified times with encapsulated C. neoformans cells and opsonizing antibody. DCs were then fixed and examined by SEM or TEM. (A) SEM of two C. neoformans yeast cells shown in the process of being phagocytosed by a DC at 10 min postincubation. Arrow points to a pseudopod from the DC attached to the yeast cell. Original magnification, ×19,000. Scale bar = 4 μm. (B) SEM of two C. neoformans yeast cells being phagocytosed by a DC at 10 min postincubation. Original magnification, ×16,000. Scale bar = 5 μm. (C) Close-up of the boxed area from panel B demonstrating a C. neoformans yeast cell partially covered by the “flap” of a DC pseudopod (arrow). Original magnification, ×50,000. Scale bar = 1 μm. (D) One C. neoformans yeast cell is seen inside a membrane-bound compartment of a DC, while another is just beginning to be phagocytosed (arrow) at 50 min postincubation. Original magnification, ×7,100. Scale bar = 2 μm. (E) A C. neoformans yeast cell is seen inside a membrane-bound compartment of a DC at 20 min postincubation. Original magnification, ×19,500. Scale bar = 0.5 μm. (F) Close-up of the boxed area from panel E demonstrating a C. neoformans cell surrounded by a contiguous endosomal membrane (arrows). Original magnification, ×40,000. Scale bar = 200 nm.

Fungicidal activity of DC-derived lysosomal extract against C. neoformans.

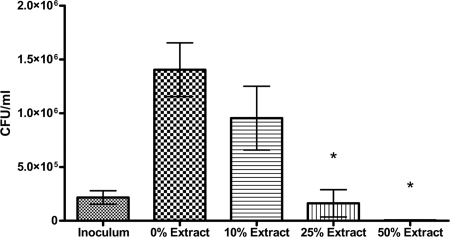

The results of the above studies demonstrated fusion of C. neoformans organisms with DC lysosomes. As the results of previous studies demonstrated that DCs kill C. neoformans (22), we next sought to determine whether lysosomes had direct antifungal activity. Lysosomes were isolated from DCs and disrupted by sonication. This crude lysosomal extract, isolated from 3 × 108 cells per ml, contained 1,000 to 1,250 mg protein and 6 to 10 units of acid phosphatase activity (a marker of lysosomal activity) per ml. In addition, prior to sonication, the crude lysosomes stained positively for LAMP-1 by confocal microscopy. The extract was incubated with C. neoformans yeast for 24 h, following which the numbers of CFU were determined. The lysosomal extracts had dose-dependent antifungal activity (Fig. 5). The inoculum was almost completely killed following the incubation of C. neoformans with 50% lysosomal extract added.

FIG. 5.

Killing of C. neoformans by lysosomal extracts from BMDCs. C. neoformans yeast cells were incubated in lysosomal buffer with the indicated concentrations of lysosomal extracts for 24 h at 37°C, following which the numbers of CFU in the wells were determined as described in Materials and Methods. The numbers of CFU in the inoculum are also shown. Data shown are means ± standard errors of the means of the results of four independent experiments, with each condition performed in duplicate. An asterisk indicates a significant difference compared to the results for 0% extract (P < 0.0001).

DISCUSSION

DCs have been shown to be involved in the phagocytosis of C. neoformans both in vivo and in vitro (22, 59). Phagocytosis and the subsequent intracellular events are critical factors determining the fate of the pathogen and the cell-mediated immune response. Previous data from our laboratory showed that pulmonary DCs exposed to C. neoformans yeast in vivo were able to present cryptococcal antigens to antigen-specific T cells ex vivo (59). In addition, BMDCs and HDCs kill complement- and antibody-opsonized C. neoformans organisms in vitro (22). Based on these data, we hypothesized that, following DC phagocytosis, C. neoformans traffics to endosomal and lysosomal compartments, where it is ultimately killed.

To determine where the C. neoformans organisms localized following DC phagocytosis, we incubated DCs with anticapsular antibody and C. neoformans yeast and examined fusion with the endosome (EEA-1) and late endosome/lysosome (LAMP-1). In human monocyte-derived macrophages, C. neoformans yeast has been shown to localize to LAMP-1-positive compartments and survive this acidic environment (29). In addition, C. neoformans can colocalize with CD63-positive compartments in immature murine DCs (2). In our current confocal microscopy studies, in both murine DCs and HDCs, phagocytosed C. neoformans organisms trafficked to endocytic compartments within 10 to 20 min and to lysosomal compartments within 30 to 60 min following fungal challenge. These findings correlated well with the results of studies of endosomal and lysosomal localization of soluble antigens that demonstrate that endosomal entry occurred between 2.5 and 10 min postuptake and lysosomal entry between 30 and 60 min postuptake (45).

Phagocytosis of organisms by DCs can proceed via different mechanisms, including the conventional zipper-type mechanism and coiling phagocytosis (6-8, 40). In order to examine the mechanisms by which DCs phagocytose C. neoformans, we performed TEM and SEM. DC phagocytosis of C. neoformans appeared to proceed through the conventional zipper-type phagocytosis mechanism, as evidenced by the presence of symmetrical pseudopods and nonoverlapping pseudopods. No evidence of coiling phagocytosis was observed. In addition, the results of TEM confirmed that phagocytosed C. neoformans organisms were indeed inside membrane-bound compartments of DCs.

Vaccination strategies designed to elicit anticapsular antibodies and passive antibody administration represent promising strategies for the prevention and treatment, respectively, of cryptococcosis (reviewed in references 10 and 11). However, the results of studies demonstrating that phagocytosis of C. neoformans yeast by HDCs is dependent upon heat-labile serum opsonins strongly suggest a predominant role for complement in phagocytosis (22). As the specific receptors mediating uptake can be critical determinants of subsequent intracellular trafficking events (reviewed in reference 4), it was important to determine whether the fate of C. neoformans differed depending upon whether entry was via complement or Fc receptors. We found that C. neoformans trafficked into the endosome and then into the lysosome regardless of whether opsonization was with complement-sufficient plasma or antibody. In contrast, recent data from examining the interaction of C. albicans with DCs found that the fate of the fungus was linked to the receptor mediating uptake. Thus, entry via dectin-1 resulted in fungal killing by stimulating NAPDH oxidase activity, whereas C. albicans could escape the oxidative damage by entering DCs through receptors not involved in NADPH oxidase activation, such as the mannose receptor, CD206 (13).

Our studies focused on early time points, and it remains possible that surviving organisms could escape the phagolysosome at later time points. While C. neoformans can be killed by DCs (22) and by macrophages (5, 27, 28), under some conditions, C. neoformans has also been shown to survive the phagolysosome of macrophages (29). Several mechanisms have been described for macrophages by which C. neoformans can escape the phagosome and even the phagocyte. C. neoformans can produce phospholipases that cause phagolysosomal membrane permeability, which can lead to the dissemination of the organism (46). In addition, growth, either by capsular expansion or budding, could mechanically disrupt the membrane. Further, recent data have shown that C. neoformans can exit from macrophages via extrusion of the phagosome (1). Whether such escape mechanisms exist for C. neoformans in DCs is not known.

Mechanisms have been described by which microbial pathogens escape killing and degradation by the lysosome of DCs. For example, Mycobacterium tuberculosis can translocate from phagolysosomes to the cytosol of DCs, thus escaping killing and degradation (57). At certain stages of its life cycle, Leishmania major resides in DC endocytic compartments where it can escape lysosomal killing by blocking the fusion of lysosomes (24). Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium is found in DC compartments that lack lysosomal markers, suggesting that this organism prevents phagolysosomal fusion (15). However, based on the results of the studies presented herein, at least in the first hour following phagocytosis, C. neoformans yeast localizes to and remains in the endosomal and lysosomal compartments of DCs.

DC killing of fungi can proceed by oxidative and/or nonoxidative mechanisms. Antifungal activity against C. neoformans was partially reduced in the presence of respiratory burst inhibitors, suggesting roles for both oxidative and nonoxidative systems (22). However, inhibitors of the respiratory burst did not affect the ability of HDCs to kill phagocytosed C. albicans or H. capsulatum (17, 38). Moreover, the addition of suramin, an inhibitor of phagosome-lysosome fusion, to Histoplasma-infected DCs inhibited phagosome-lysosome fusion and DC fungicidal activity (17). Lysosomal killing and degradation by DCs could be important for both pathogen clearance and MHC-restricted antigen presentation to naïve T cells. Therefore, we determined whether lysosomal components from DCs were capable of killing C. neoformans. We found that crude lysosomal extracts from DCs had dose-dependent anticryptococcal activity, with nearly complete killing observed when the extracts were diluted 50%. Current studies in our laboratory are focused on determining the antifungal effectors in DC lysosomes that are responsible for killing C. neoformans. For human neutrophils, multiple peptides and proteins, including defensins, have been shown to kill C. neoformans (33).

In summary, we have shown that C. neoformans traffics into the endosomal and lysosomal compartments of HDCs and murine DCs following phagocytosis. In addition, this trafficking was independent of the method of opsonization, suggesting that multiple mechanisms exist for the entry of phagocytosed organisms into the endosomal pathway. Moreover, we have shown that purified lysosomal components of DCs are able to kill C. neoformans. Based on the data presented herein, we suggest that the intracellular trafficking and delivery of C. neoformans organisms to the lysosome for degradation may be important in the antigen presentation of cryptococcal antigens to T cells. DCs play a key role in the host defense against several pathogenic microorganisms by initiating adaptive cell-mediated immune responses. Understanding the interaction of DCs and their lysosomal components with C. neoformans yeast will help in gaining insights into its pathogenesis and may also lead to the development of innovative immunotherapies to help control cryptococcal infection.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Tom Kozel for providing the 3C2 opsonizing antibody and Gregory Hendricks for assistance in electron microscopy.

This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health grants RO1 AI25780 and RO1 AI066087.

Editor: A. Casadevall

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 4 August 2008.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://iai.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alvarez, M., and A. Casadevall. 2006. Phagosome extrusion and host-cell survival after Cryptococcus neoformans phagocytosis by macrophages. Curr. Biol. 162161-2165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Artavanis-Tsakonas, K., J. C. Love, H. L. Ploegh, and J. M. Vyas. 2006. Recruitment of CD63 to Cryptococcus neoformans phagosomes requires acidification. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 10315945-15950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Banchereau, J., F. Briere, C. Caux, J. Davoust, S. Lebecque, Y. T. Liu, B. Pulendran, and K. Palucka. 2000. Immunobiology of dendritic cells. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 18767-811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blander, J. M. 2007. Signalling and phagocytosis in the orchestration of host defence. Cell Microbiol. 9290-299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bolanos, B., and T. G. Mitchell. 1989. Killing of Cryptococcus neoformans by rat alveolar macrophages. J. Med. Vet. Mycol. 27219-228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bouis, D. A., T. G. Popova, A. Takashima, and M. V. Norgard. 2001. Dendritic cells phagocytose and are activated by Treponema pallidum. Infect. Immun. 69518-528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bozza, S., R. Gaziano, A. Spreca, A. Bacci, C. Montagnoli, P. di Francesco, and L. Romani. 2002. Dendritic cells transport conidia and hyphae of Aspergillus fumigatus from the airways to the draining lymph nodes and initiate disparate Th responses to the fungus. J. Immunol. 1681362-1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brittingham, K. C., G. Ruthel, R. G. Panchal, C. L. Fuller, W. J. Ribot, T. A. Hoover, H. A. Young, A. O. Anderson, and S. Bavari. 2005. Dendritic cells endocytose Bacillus anthracis spores: implications for anthrax pathogenesis. J. Immunol. 1745545-5552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cross, A. R., and A. W. Segal. 2004. The NADPH oxidase of professional phagocytes-prototype of the NOX electron transport chain systems. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 16571-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dan, J. M., and S. M. Levitz. 2006. Prospects for development of vaccines against fungal diseases. Drug Resist. Updat. 9105-110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Datta, K., and L.-A. Pirofski. 2006. Towards a vaccine for Cryptococcus neoformans: principles and caveats. FEMS Yeast Res. 6525-536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Delamarre, L., H. Holcombe, and I. Mellman. 2003. Presentation of exogenous antigens on major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I and MHC class II molecules is differentially regulated during dendritic cell maturation. J. Exp. Med. 198111-122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Donini, M., E. Zenaro, N. Tamassia, and S. Dusi. 2007. NADPH oxidase of human dendritic cells: role in Candida albicans killing and regulation by interferons, Dectin-1 and CD206. Eur. J. Immunol. 371194-1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.d'Ostiani, C. F., G. Del Sero, A. Bacci, C. Montagnoli, A. Spreca, A. Mencacci, P. Ricciardi-Castagnoli, and L. Romani. 2000. Dendritic cells discriminate between yeasts and hyphae of the fungus Candida albicans: implications for initiation of T helper cell immunity in vitro and in vivo. J. Exp. Med. 1911661-1673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garcia-Del Portillo, F., H. Jungnitz, M. Rohde, and C. A. Guzman. 2000. Interaction of Salmonella enterica serotype Typhimurium with dendritic cells is defined by targeting to compartments lacking lysosomal membrane glycoproteins. Infect. Immun. 682985-2991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Geuze, H. J. 1998. The role of endosomes and lysosomes in MHC class II functioning. Immunol. Today 19282-287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gildea, L. A., G. M. Ciraolo, R. E. Morris, and S. L. Newman. 2005. Human dendritic cell activity against Histoplasma capsulatum is mediated via phagolysosomal fusion. Infect. Immun. 736803-6811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hill, J. O., and A. G. Harmsen. 1991. Intrapulmonary growth and dissemination of an avirulent strain of Cryptococcus neoformans in mice depleted of CD4+ or CD8+ T-cells. J. Exp. Med. 173755-758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huffnagle, G. B., M. F. Lipscomb, J. A. Lovchik, K. A. Hoag, and N. E. Street. 1994. The role of CD4(+) and CD8(+) T-cells in the protective inflammatory response to a pulmonary cryptococcal infection. J. Leukoc. Biol. 5535-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huffnagle, G. B., J. L. Yates, and M. F. Lipscomb. 1991. Immunity to a pulmonary Cryptococcus neoformans infection requires both CD4+ and CD8+ T-cells. J. Exp. Med. 173793-800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huffnagle, G. B., J. L. Yates, and M. F. Lipscomb. 1991. T-cell-mediated immunity in the lung: a Cryptococcus neoformans pulmonary infection model using SCID and athymic nude mice. Infect. Immun. 591423-1433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kelly, R. M., J. M. Chen, L. E. Yauch, and S. M. Levitz. 2005. Opsonic requirements for dendritic cell-mediated responses to Cryptococcus neoformans. Infect. Immun. 73592-598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kleijmeer, M. J., G. Raposo, and H. J. Geuze. 1996. Characterization of MHC class II compartments by immunoelectron microscopy. Methods 10191-207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Korner, U., V. Fuss, J. Steigerwald, and H. Moll. 2006. Biogenesis of Leishmania major-harboring vacuoles in murine dendritic cells. Infect. Immun. 741305-1312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Levitz, S. M. 1991. The ecology of Cryptococcus neoformans and the epidemiology of cryptococcosis. Rev. Infect. Dis. 131163-1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Levitz, S. M. 2002. Receptor-mediated recognition of Cryptococcus neoformans. Nippon Ishinkin Gakkai Zasshi 43133-136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Levitz, S. M., and D. J. Dibenedetto. 1989. Paradoxical role of capsule in murine bronchoalveolar macrophage-mediated killing of Cryptococcus neoformans. J. Immunol. 142659-665. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Levitz, S. M., T. S. Harrison, A. Tabuni, and X. P. Liu. 1997. Chloroquine induces human mononuclear phagocytes to inhibit and kill Cryptococcus neoformans by a mechanism independent of iron deprivation. J. Clin. Investig. 1001640-1646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Levitz, S. M., S. H. Nong, K. F. Seetoo, T. S. Harrison, R. A. Speizer, and E. R. Simons. 1999. Cryptococcus neoformans resides in an acidic phagolysosome of human macrophages. Infect. Immun. 67885-890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lutz, M. B., N. Kukutsch, A. L. J. Ogilvie, S. Rossner, F. Koch, N. Romani, and G. Schuler. 1999. An advanced culture method for generating large quantities of highly pure dendritic cells from mouse bone marrow. J. Immunol. Methods 22377-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lutz, M. B., P. Rovere, M. J. Kleijmeer, M. Rescigno, C. U. Assmann, V. M. Oorschot, H. J. Geuze, J. Trucy, D. Demandolx, J. Davoust, and P. Ricciardi-Castagnoli. 1997. Intracellular routes and selective retention of antigens in mildly acidic cathepsin D/lysosome-associated membrane protein-1/MHC class II-positive vesicles in immature dendritic cells. J. Immunol. 1593707-3716. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.MacMicking, J., Q.-W. Xie, and C. Nathan. 1997. Nitric oxide and macrophage function. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 15323-350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mambula, S. S., E. R. Simons, R. Hastey, M. E. Selsted, and S. M. Levitz. 2000. Human neutrophil-mediated nonoxidative antifungal activity against Cryptococcus neoformans. Infect. Immun. 686257-6264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mellman, I. 2005. Antigen processing and presentation by dendritic cells: cell biological mechanisms. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 56063-67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mitchell, T. G., and J. R. Perfect. 1995. Cryptococcosis in the era of AIDS: 100 years after the discovery of Cryptococcus neoformans. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 8515-548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mody, C. H., M. F. Lipscomb, N. E. Street, and G. B. Toews. 1990. Depletion of CD4+ (L3T4+) lymphocytes in vivo impairs murine host defense to Cryptococcus neoformans. J. Immunol. 1441472-1477. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Murphy, J. W. 1998. Protective cell-mediated immunity against Cryptococcus neoformans. Res. Immunol. 149373-386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Newman, S. L., and A. Holly. 2001. Candida albicans is phagocytosed, killed, and processed for antigen presentation by human dendritic cells. Infect. Immun. 696813-6822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Qin, Z. H., G. Noffz, M. Mohaupt, and T. Blankenstein. 1997. Interleukin-10 prevents dendritic cell accumulation and vaccination with granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor gene-modified tumor cells. J. Immunol. 159770-776. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rittig, M. G., K. Schröppel, K.-H. Seack, U. Sander, E. N. N′Diaye, I. Maridonneau-Parini, W. Solbach, and C. Bogdan. 1998. Coiling phagocytosis of trypanosomatids and fungal cells. Infect. Immun. 664331-4339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rocha, N., and J. Neefjes. 2008. MHC class II molecules on the move for successful antigen presentation. EMBO J. 271-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Roseff, S. A., and S. M. Levitz. 1993. Effect of endothelial cells on phagocyte-mediated anticryptococcal activity. Infect. Immun. 613818-3824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rous, B. A., B. J. Reaves, G. Ihrke, J. A. G. Briggs, S. R. Gray, D. J. Stephens, G. Banting, and J. P. Luzio. 2002. Role of adaptor complex AP-3 in targeting wild-type and mutated CD63 to lysosomes. Mol. Biol. Cell 131071-1082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sallusto, F., and A. Lanzavecchia. 1994. Efficient presentation of soluble antigen by cultured human dendritic cells is maintained by granulocyte/macrophage colony-stimulating factor plus interleukin 4 and downregulated by tumor necrosis factor alpha. J. Exp. Med. 1791109-1118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Scott, C. C., R. J. Botelho, and S. Grinstein. 2003. Phagosome maturation: a few bugs in the system. J. Membr. Biol. 193137-152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shea, J. M., T. B. Kechichian, C. Luberto, and M. Del Poeta. 2006. The cryptococcal enzyme inositol phosphosphingolipid-phospholipase C confers resistance to the antifungal effects of macrophages and promotes fungal dissemination to the central nervous system. Infect. Immun. 745977-5988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shoham, S., and S. M. Levitz. 2005. The immune response to fungal infections. Br. J. Haematol. 129569-582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shortman, K., and Y. J. Liu. 2002. Mouse and human dendritic cell subtypes. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2151-161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Singh, N., T. Gayowski, M. M. Wagener, and I. R. Marino. 1997. Clinical spectrum of invasive cryptococcosis in liver transplant recipients receiving tacrolimus. Clin. Transplant. 1166-70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Spiropulu, C., R. A. Eppard, E. Otteson, and T. R. Kozel. 1989. Antigenic variation within serotypes of Cryptococcus neoformans detected by monoclonal antibodies specific for the capsular polysaccharide. Infect. Immun. 573240-3242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Taborda, C. P., and A. Casadevall. 2002. CR3 (CD11b/CD18) and CR4 (CD11c/CD18) are involved in complement-independent antibody-mediated phagocytosis of Cryptococcus neoformans. Immunity 16791-802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tjelle, T. E., T. Lovdall, and T. Berg. 2000. Phagosome dynamics and function. BioEssays 22255-263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Torres, M., L. Ramachandra, R. E. Rojas, K. Bobadilla, J. Thomas, D. H. Canaday, C. V. Harding, and W. H. Boom. 2006. Role of phagosomes and major histocompatibility complex class II (MHC-II) compartment in MHC-II antigen processing of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in human macrophages. Infect. Immun. 741621-1630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Trombetta, E. S., M. Ebersold, W. Garrett, M. Pypaert, and I. Mellman. 2003. Activation of lysosomal function during dendritic cell maturation. Science 2991400-1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Trombetta, E. S., and I. Mellman. 2005. Cell biology of antigen processing in vitro and in vivo. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 23975-1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Upham, J. W. 2003. The role of dendritic cells in immune regulation and allergic airway inflammation. Respirology 8140-148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.van der Wel, N., D. Hava, D. Houben, D. Fluitsma, M. van Zon, J. Pierson, M. Brenner, and P. J. Peters. 2007. M. tuberculosis and M. leprae translocate from the phagolysosome to the cytosol in myeloid cells. Cell 1291287-1298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Vogt, A. B., S. Spindeldreher, and H. Kropshofer. 2002. Clustering of MHC-peptide complexes prior to their engagement in the immunological synapse: lipid raft and tetraspan microdomains. Immunol. Rev. 189136-151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wozniak, K. L., J. M. Vyas, and S. M. Levitz. 2006. In vivo role of dendritic cells in a murine model of pulmonary cryptococcosis. Infect. Immun. 743817-3824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhou, D., P. Li, Y. Lin, J. M. Lott, A. D. Hislop, D. H. Canaday, R. R. Brutkiewicz, and J. S. Blum. 2005. LAMP-2a facilitates MHC class II presentation of cytoplasmic antigens. Immunity 22571-581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.