Abstract

S acylation of cysteines located in the transmembrane and/or cytoplasmic region of influenza virus hemagglutinins (HA) contributes to the membrane fusion and assembly of virions. Our results from using mass spectrometry (MS) show that influenza B virus HA possessing two cytoplasmic cysteines contains palmitate, whereas HA-esterase-fusion glycoprotein of influenza C virus having one transmembrane cysteine is stearoylated. HAs of influenza A virus having one transmembrane and two cytoplasmic cysteines contain both palmitate and stearate. MS analysis of recombinant viruses with deletions of individual cysteines, as well as tandem-MS sequencing, revealed the surprising result that stearate is exclusively attached to the cysteine positioned in the transmembrane region of HA.

All hemagglutinating glycoproteins of influenza viruses are S acylated at cysteines, but differ in the number and location of their acylation sites (17). Hemagglutinin (HA) from influenza A virus is acylated at three highly conserved cysteines, two of which are located in the cytoplasmic tail (CT) and one at the carboxy-terminal end of the transmembrane region (6, 7, 11, 15). HA from influenza B virus is acylated at two cysteines in its CT, and the HA-esterase-fusion glycoprotein (HEF) of influenza C virus is acylated at a single cysteine located at the boundary between the transmembrane region (TMR) and the CT (12, 16). The hydrophobic modification is essential for virus replication, since (depending on the virus strain) virus mutants with more than one acylation site deleted either showed drastically impaired growth or could not be created at all by reverse genetics (1, 19, 21). S acylation of the HA of influenza A virus (subtypes H1 and H7) and of influenza B virus was shown to be required for membrane fusion, especially for the opening or enlargement of the fusion pore (6, 8, 12, 13, 19). In contrast, influenza A mutants containing nonacylated subtype H3 HA show full fusion, but budding of virus particles was reduced (1).

S acylation is usually demonstrated by metabolic labeling of viruses with [3H]palmitate, since this fatty acid is predominant in most acylproteins, and hence, the name palmitoylation is often used. Although it was recognized early on that “palmitoylation” is not specific for this carbon chain (9), the exact fatty acid composition of S-acylated proteins has been difficult to determine. Most analyses relied on chromatographic determination of protein-bound, 3H-labeled fatty acid. Since [3H]palmitate used for labeling can be converted into other carbon chains prior to attachment to acylproteins, this allows a rough estimation of a protein's fatty acid pattern, but it is not known whether the results obtained do reflect the actual fatty acid content of acylproteins. With this methodology, we have previously reported that HAs of influenza viruses are S acylated with different fatty acids. Whereas HAs of influenza A and B virus contain mainly palmitic acid, HEF is unique in this respect, since it is acylated predominantly with stearic acid (14, 16). Advancements in mass spectrometry (MS) now allow the precise quantification of the fatty acid species linked to an acylprotein or even to a single acylation site. Presently it is not known for HA (or for any other acylprotein with multiple acylation sites and more than one protein-bound fatty acid species) whether each cysteine has the same fatty acid content or contains different carbon chains.

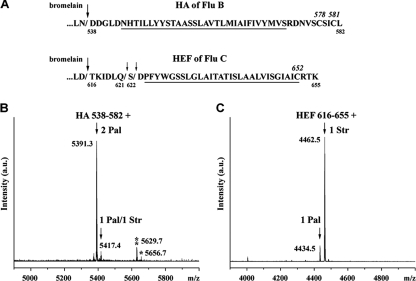

Using our recently developed method (2, 10) we determined the fatty acid species attached to the hemagglutinating glycoproteins of influenza B and C viruses. Briefly, influenza virions purified from embryonated eggs were digested with bromelain in nonreducing conditions to remove the ectodomain of HA. The subviral particles were extracted with chloroform-methanol, and the organic phase containing the anchoring fragment of the glycoproteins was subjected to matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight (MALDI-TOF) MS. The mass spectrum of HA from influenza B virus (B/Hong Kong/8/73) contains one major peak (96.9 ± 0.8% [mean ± standard deviation]) with a mass of 5,391.3, which matches the C-terminal fragment of HA spanning amino acids 538 to 582 plus two palmitates (Fig. 1A and B). A minor peak (3.1 ± 0.8%) with a mass of 5,417.4 was detected, which represents the same peptide containing one palmitate and one stearate. Almost identical results (97.6% dipalmitoylated and 2.4% monopalmitoylated/monostearoylated peptide) were obtained with the Victoria/2/87 strain of influenza B virus. The mass spectrum obtained from HEF of influenza C virus contains a major peak (87.9 ± 1.3) with an m/z value of 4,462.5, which corresponds to the monostearoylated TMR and CT of HEF (Fig. 1A and C). Only minor amounts (12.1 ± 1.3%) of a monopalmitoylated peptide were observed. Thus, the two cysteine residues located in the CT of HA of influenza B virus contain almost exclusively palmitate, whereas HEF of influenza C virus is acylated with stearate. This is not a feature peculiar to egg-grown viruses, since similar results were obtained after the growth of influenza C virus in mammalian cells (14, 16).

FIG. 1.

Results of MALDI-TOF MS analysis of fatty acid species attached to influenza B virus HA and influenza C virus HEF. (A) Sequences of the C terminus of HA from B/Hong Kong/8/73 (Flu B) and HEF from C/Johannesburg/1/66 (Flu C) indicating sites of cleavage by bromelain (arrows) and the TMR (underlined). Bromelain preferentially cleaves HEF after aspartic acid 615 (large arrow); in additional experiments, cleavage after glutamine 621 and serine 622 (small arrows) was also noticed. (B and C) Results of MALDI-TOF MS analysis. Mass spectra of indicated peptides plus palmitate and/or stearate obtained in reflector mode with pointed average masses are represented. (B) HA from influenza B virus. Additional pair of peaks were identified which matched to triply palmitoylated (m/z 5629.7; two asterisks) and doubly palmitoylated/monostearoylated (m/z 5656.7; one asterisk) peptides, which may indicate substoichiometric O-acylation of a serine located at the boundary between the TMR and CT or in the CT. (C) HEF from influenza C virus. Pal, palmitate; Str, stearate; a.u., arbitrary unit. Italic position numbers mark the numbers of acylated cysteine residues, and nonitalic position numbers mark the starting and ending numbers of the isolated peptides.

We then determined the fatty acid species attached to 10 HAs of five different subtypes from influenza A virus. All HAs, including those from the H5 subtype not previously tested for acylation, contain primarily palmitate but also, depending on the virus strain, substantial amounts of stearate (Table 1). The amount of stearate reached values of 12% (subtype H1), approximately 25% (subtype H3 and one subtype H5 strain), and up to 30 to 35% (subtypes H7 and H10 and most H5 strains). Two subtype H1 strains with almost-identical amounts of stearate (11.6 or 12.6%) differ in one, but a conservative, amino acid located in the ectodomain of HA (Ile versus Val) (Table 1). In contrast, minor variations in the amount of stearate (3 to 9%) within the same HA subtype are accompanied by a nonconservative exchange (Thr versus Ile) in the extraviral part of HA or in single amino acid substitutions in the vicinity of the transmembrane cysteine. Larger variations in the stearate content, for example, 20% between one subtype H5 strain and the subtype H1 strain, go along with the exchange of eight hydrophobic amino acids in the TMR (Table 1). However, all these amino acid exchanges do not affect S acylation per se. Since only minor peaks corresponding to underacylated peptides, which are about 2 to 3% of the whole acylation pattern, were detected, all cysteine residues of HA are (almost) stoichiometrically acylated, either with palmitate or with stearate. Yet, it cannot be deduced from the data presented so far whether a given cysteine is acylated heterogeneously or exclusively with only one fatty acid species.

TABLE 1.

Comparison of amino acid sequences and amount of stearate determined by MALDI-TOF MS

| Virus | Amino acid sequencec | Amt of stearate (%)d |

|---|---|---|

| Influenza A virus strains | ||

| Puerto Rico/8/34 (H1N1)a,b | LESMGIYQILAIYSTVASSLVLLVSLGAISFWMcSNGSLQcRIcI | 12.6 ± 1.7 |

| New Caledonia/20/99 (H1N1)b | LESMGVYQILAIYSTVASSLVLLVSLGAISFWMcSNGSLQcRIcI | 11.6 ± 1.2 |

| Duck/Vietnam/342/2001 (H5N1) | LESIGTYQILSIYSTVASSLALAIMVAGLSFWMcSNGSLQcRIcI | 32.0 ± 3.3 |

| Mallard/Penn/1024/84 (H5N2)b | LESMGTYQILSIYSTVASSLALAIMVAGLSFWMcSNGSLQcRIcI | 29.3 ± 0.8 |

| NIBRG-14(HA Viet/1194/04;H5N1)b | LESIGIYQILSIYSTVASSLALAIMVAGLSLWMcSNGSLQcRIcI | 23.1 ± 2.5 |

| X-31(HA of Aichi/2/68; H3N2)a,b | SGYKDWILWISFAISCFLLCVVLLGFIMWAcQRGNIRcNIcI | 26.5 ± 1.0 |

| Beijing/32/92 (H3N2) | SGYKDWILWISFAISCFLLCVVLLGFIMWAcQKGNIRcNIcI | 23.0 ± 0.1 |

| FPV/Weybridge/34 (H7N7)a,b | LSGGYKDVILWFSFGASCFLLLAIAMGLVFIcVKYGNMRcTIcI | 33.0 ± 0.9 |

| FPV/Rostock/34 wt (H7N1)b | LSSGYKDVILWFSFGASCFLLLAIAMGLVFIcVKNGNMRcTIcI | 30.1 ± 0.4 |

| FPV/Rostock/34 Ac1 mutantb | LSSGYKDVILWFSFGASCFLLLAIAMGLVFISVKNGNMRcTIcI | 4.0 ± 1.6 |

| FPV/Rostock/34 Ac2 mutantb | LSSGYKDVILWFSFGASCFLLLAIAMGLVFIcVKNGNMRSTIcI | 46.0 ± 0.4 |

| FPV/Rostock/34 Ac3 mutantb | LSSGYKDVILWFSFGASCFLLLAIAMGLVFIcVKNGNMRcTISI | 46.0 ± 1.2 |

| Chicken/Germany/N/49(H10N7) | LSSGYKDIILWFSFGASCFVLLAAVMGLVFFcLKNGNMQcTIcI | 35.1 ± 0.9 |

| Influenza B and C virus strains | ||

| B/Victoria/2/87b | DDGLDNHTILLYYSTAASSLAVTLMIAIFIVYMVSRDNVScSIcL | 2.4 ± 0.9 |

| B/Hong Kong/8/73 | DDGLDNHTILLYYSTAASSLAVTLMIAIFIVYMVSRDNVScSIcL | 3.1 ± 0.8 |

| C/Johannesburg/1/66b | TKIDLQSDPFYWGSSLGLAITATISLAALVISGIAIcRTK | 87.9 ± 1.3 |

Results were calculated from the raw data published previously (10).

Calculations were made from the results for at least two different virus preparations. For each virus preparation, two or three bromelain digestions were performed and at least four mass spectra were recorded as the sum of at least 200 laser shots.

Results were confirmed by MS-MS sequencing (except for X-31, which resisted fragmentation). TMRs are underlined, acylated cysteines are in lowercase, and amino acid exchanges within one subtype are shown in boldface and between H1/H5 and H7/H10 subtypes are in italics and bold.

The remainder is palmitate; results are represented as the mean ± standard deviation.

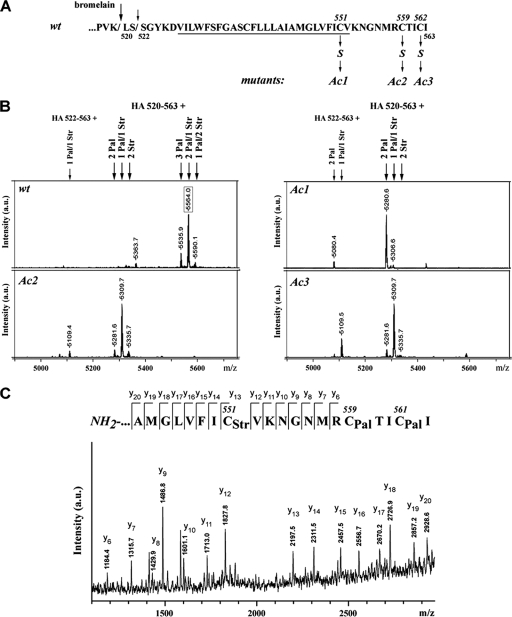

To address this question, we determined the HA-linked fatty acids of three recombinant variants of fowl plague virus (FPV), each having one of the acylated cysteines replaced with a serine (Fig. 2A) (19). In mutants of HA where one of the two cytoplasmic cysteines are deleted (Ac2 and Ac3), the amount of stearate is increased to 46% relative to the amount in wild-type HA (30%) (Fig. 2B). In contrast, mutant Ac1 with a deletion of the transmembrane cysteine contains only minor amounts of stearate (4% ± 1.6), suggesting that the transmembrane cysteine is the site of stearate attachment in the wild-type protein. This assumption was directly proven by tandem-MS (MS-MS) sequencing of the anchoring fragment obtained from wild-type HA. Its major peptide parent ion, with an m/z value of 5,564, which contains two palmitates and one stearate (Fig. 2B), was subjected to MS-MS fragmentation analysis (Fig. 2C). The y13 to y12 ion mass shift representing cysteine 551 reveals an additional shift of 266 units. This is the mass value of stearate and, hence, direct proof that stearate is linked to the transmembrane cysteine 551. A mass shift of 476 units (238 × 2) detected for the y6 ion covering amino acids 558 to 562 implies that both cytoplasmic cysteines in positions 559 and 561 possess palmitate. The results of MS-MS sequencing also indicate site-specific attachment of stearate to the transmembrane cysteine of HAs obtained from the influenza viruses listed in Table 1 (except for subtypes H1 and X-31; the peptide of the latter did not fragment) and, previously, to the HA of FPV (Weybridge) (10).

FIG. 2.

Results of MALDI-TOF MS analysis of fatty acid species attached to influenza A virus HA (FPV/Rostock/34, H7N1) and to HA mutants from recombinant virus with replacement of individual acylation sites. (A) Sequence of the C terminus of wild-type (wt) HA indicating the two sites of cleavage by bromelain (arrows), the TMR (underlined), and nomenclature of acylation mutants Ac1, Ac2, and Ac3 generated by exchanging cysteines for serines at positions 551, 559, and 562, respectively (19). (B) Results of MALDI-TOF MS analysis. Mass spectra of indicated peptides plus palmitate and/or stearate obtained in reflector mode with pointed average masses are represented. The m/z value of a parent ion subjected to MS-MS fragmentation analysis (see C) is boxed. Bromelain cleaves this HA at two distinct sites, preferentially after lysine 519 (large arrows) but also after serine 521 (small arrows). Thus, two different peptides were observed, a major peptide spanning amino acid 520 to the end of HA at amino acid 563 but also a smaller peptide starting at amino acid 522. The peptides generated from the cysteine mutants of HA have lower m/z values due to the exchange of serine for cysteine and the concomitant lack of one acyl chain. Italic position numbers mark the numbers of acylated cysteine residues, and nonitalic position numbers mark the starting and ending numbers of the isolated peptides. (C) Results of MS-MS sequencing of the FPV/Rostock/34 (wild type) HA C-terminal anchoring peptide. Shown is a part of the MALDI-TOF-TOF mass spectrum of the parent ion from peptide [HA 520-563 + 2Pal/1Str] (m/z 5564.0; boxed in panel B). A series of detected average masses and corresponding C-terminal daughter y ions are designated. Their matching to the amino acid sequence is depicted above the mass spectrum. Pal, palmitate; Str, stearate; a.u., arbitrary unit.

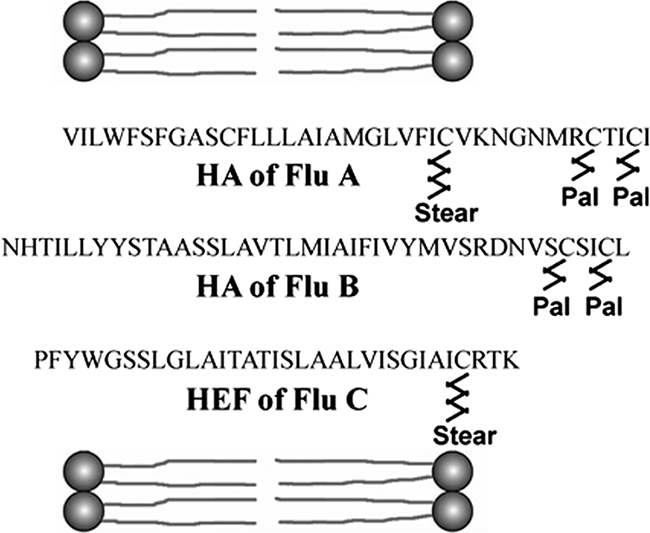

In summary, HA is palmitoylated at the two cysteines in its CT and stearoylated at the cysteine located at the boundary between the TMR and CT (Fig. 3). Thus, the enzyme(s) responsible for S acylation of HA must recognize whether a particular cysteine should be acylated with palmitate or with stearate. The main determinant is probably the location of the cysteine relative to the membrane bilayer, but amino acids in the vicinity of the transmembrane cysteine also have an effect on the extent of stearoylation. The site-specific attachment of palmitate and stearate suggests that two different enzymes perform S acylation of HA. The enzymes responsible for the acylation of viral glycoproteins have not been identified, but DHHC-CRD proteins are likely candidates since they were shown to palmitoylate cellular proteins (3). DHHC-CRD proteins are polytopic membrane proteins present at diverse intracellular locations, including the endoplasmic reticulum and the Golgi apparatus, the intracellular site where acylation of HA occurs (18). Since the DHHC-CRD family contains 23 members, it is likely that individual enzymes differ in their acyl-coenzyme A and substrate specificities.

FIG. 3.

Summary of the MS data. The putative TMRs (embedded in lipids) and CTs of HA of influenza A and B virus (Flu A and B) and HEF of influenza C virus (Flu C), with palmitate (Pal) and stearate (Stear) attached to individual cysteine residues, are shown.

S acylation is believed to target HA to membrane rafts, nanodomains of the plasma membrane enriched in cholesterol and sphingolipids (4, 20). One would assume that the longer and thus more-hydrophobic acyl chain of stearate is more important for the raft localization of HA than the shorter acyl chain of palmitate. Stearic acid might even interdigitate into the outer leaflet of membranes, thereby coupling inner-leaflet with outer-leaflet domains. Indeed, FPV virions containing the nonstearoylated mutant Ac1 of HA had a more-pronounced reduction of raft lipids in their envelope than those containing Ac2 and Ac3 (19). Conflicting data regarding the impact of individual acylation sites on the raft association of HA have been reported (1, 19), but in these studies, the raft localization of HA was assessed as insolubility in detergent, a questionable criterion for the raft association of proteins (5). We believe that site-specific S acylation with palmitate or stearate, which is likely to occur also in other viral and cellular acylproteins, influences the affinity of the TMR and CT of HA for specific lipids. Since HA is doing work on membranes during the entry and budding of virions, stable or transient binding to a variety of lipids might be an essential prerequisite for the protein to fulfill its function.

Acknowledgments

We thank Hans-Dieter Klenk for recombinant FPV, Valeria Ivanova, Stanislav Markushin, and Ekaterina Kropotkina for other virus strains, and Ingrid Poese for technical assistance.

Funding was provided by the DFG (SPP 1175 and SFB 740), by ISTC grant number 2816P, and by RFBR grant number 06-04-48728.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 2 July 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chen, B. J., M. Takeda, and R. A. Lamb. 2005. Influenza virus hemagglutinin (h3 subtype) requires palmitoylation of its cytoplasmic tail for assembly: m1 proteins of two subtypes differ in their ability to support assembly. J. Virol. 7913673-13684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kordyukova, L. V., A. L. Ksenofontov, M. V. Serebryakova, T. V. Ovchinnikova, N. V. Fedorova, V. T. Ivanova, and L. A. Baratova. 2004. Influenza A hemagglutinin C-terminal anchoring peptide: identification and mass spectrometric study. Protein Pept. Lett. 11385-391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Linder, M. E., and R. J. Deschenes. 2007. Palmitoylation: policing protein stability and traffic. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 874-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Melkonian, K. A., A. G. Ostermeyer, J. Z. Chen, M. G. Roth, and D. A. Brown. 1999. Role of lipid modifications in targeting proteins to detergent-resistant membrane rafts. Many raft proteins are acylated, while few are prenylated. J. Biol. Chem. 2743910-3917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Munro, S. 2003. Lipid rafts: elusive or illusive? Cell 115377-388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Naeve, C. W., and D. Williams. 1990. Fatty acids on the A/Japan/305/57 influenza virus hemagglutinin have a role in membrane fusion. EMBO J. 93857-3866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Naim, H. Y., B. Amarneh, N. T. Ktistakis, and M. G. Roth. 1992. Effects of altering palmitylation sites on biosynthesis and function of the influenza virus hemagglutinin. J. Virol. 667585-7588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sakai, T., R. Ohuchi, and M. Ohuchi. 2002. Fatty acids on the A/USSR/77 influenza virus hemagglutinin facilitate the transition from hemifusion to fusion pore formation. J. Virol. 764603-4611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schmidt, M. F. 1984. The transfer of myristic and other fatty acids on lipid and viral protein acceptors in cultured cells infected with Semliki Forest and influenza virus. EMBO J. 32295-2300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Serebryakova, M. V., L. V. Kordyukova, L. A. Baratova, and S. G. Markushin. 2006. Mass spectrometric sequencing and acylation character analysis of C-terminal anchoring segment from influenza A hemagglutinin. Eur. J. Mass Spectrom. 1251-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Steinhauer, D. A., S. A. Wharton, D. C. Wiley, and J. J. Skehel. 1991. Deacylation of the hemagglutinin of influenza A/Aichi/2/68 has no effect on membrane fusion properties. Virology 184445-448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ujike, M., K. Nakajima, and E. Nobusawa. 2004. Influence of acylation sites of influenza B virus hemagglutinin on fusion pore formation and dilation. J. Virol. 7811536-11543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ujike, M., K. Nakajima, and E. Nobusawa. 2005. Influence of additional acylation site(s) of influenza B virus hemagglutinin on syncytium formation. Microbiol. Immunol. 49355-359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Veit, M., G. Herrler, M. F. Schmidt, R. Rott, and H. D. Klenk. 1990. The hemagglutinating glycoproteins of influenza B and C viruses are acylated with different fatty acids. Virology 177807-811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Veit, M., E. Kretzschmar, K. Kuroda, W. Garten, M. F. Schmidt, H. D. Klenk, and R. Rott. 1991. Site-specific mutagenesis identifies three cysteine residues in the cytoplasmic tail as acylation sites of influenza virus hemagglutinin. J. Virol. 652491-2500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Veit, M., H. Reverey, and M. F. Schmidt. 1996. Cytoplasmic tail length influences fatty acid selection for acylation of viral glycoproteins. Biochem. J. 318163-172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Veit, M., and M. F. Schmidt. 2006. Palmitoylation of influenza virus proteins. Berl. Munch. Tierarztl. Wochenschr. 119112-122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Veit, M., and M. F. Schmidt. 1993. Timing of palmitoylation of influenza virus hemagglutinin. FEBS Lett. 336243-247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wagner, R., A. Herwig, N. Azzouz, and H. D. Klenk. 2005. Acylation-mediated membrane anchoring of avian influenza virus hemagglutinin is essential for fusion pore formation and virus infectivity. J. Virol. 796449-6458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang, J., A. Pekosz, and R. A. Lamb. 2000. Influenza virus assembly and lipid raft microdomains: a role for the cytoplasmic tails of the spike glycoproteins. J. Virol. 744634-4644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zurcher, T., G. Luo, and P. Palese. 1994. Mutations at palmitylation sites of the influenza virus hemagglutinin affect virus formation. J. Virol. 685748-5754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]