Abstract

HCF-1 is a cellular transcriptional coactivator that is critical for mediating the regulated expression of the immediate-early genes of the alphaherpesviruses herpes simplex virus type 1 and varicella-zoster virus. HCF-1 functions, at least in part, by modulating the modification of nucleosomes at these viral promoters to reverse cell-mediated repressive marks and promote activating marks. Strikingly, HCF-1 is specifically sequestered in the cytoplasm of sensory neurons where these viruses establish latency and is rapidly relocalized to the nucleus upon stimuli that result in viral reactivation. However, the analysis of HCF-1 in latently infected neurons and the protein's specific subcellular location have not been determined. Therefore, in this study, the localization of HCF-1 in unstimulated and induced latently infected sensory neurons was investigated and was found to be similar to that observed in uninfected mice, with a time course of induced nuclear accumulation that correlated with viral reactivation. Using a primary neuronal cell culture system, HCF-1 was localized to the Golgi apparatus in unstimulated neurons, a unique location for a transcriptional coactivator. Upon disruption of the Golgi body, HCF-1 was rapidly relocalized to the nucleus in contrast to other Golgi apparatus-associated proteins. The location of HCF-1 is distinct from that of CREB3, an endoplasmic reticulum-resident HCF-1 interaction partner that has been proposed to sequester HCF-1. The results support the model that HCF-1 is an important component of the viral latency-reactivation cycle and that it is regulated by association with a component that is distinct from the identified HCF-1 interaction factors.

HCF-1 is a cellular transcription coactivator consisting of amino- and carboxy-terminal subunits generated by site-specific proteolytic processing of a 220-kDa precursor protein (19, 43). The protein was originally identified as a required component of the herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) immediate-early (IE) gene enhancer core complex in association with the cellular POU-homeodomain protein Oct-1 and the viral IE transactivator VP16 (18, 20, 42). It has since been shown to be essential for the complex combinatorial regulation of the IE genes of both HSV-1 and varicella-zoster virus (31). The requirement for HCF-1 for the function of multiple transcription factors that regulate the IE genes suggests that it must mediate a common rate-limiting step in transcription initiation and that induction of the viral IE genes is therefore determined at the level of the coactivator.

Biochemically, HCF-1 has been identified as a component of several chromatin modification complexes including that of the Set1/MLL1 methyltransferase, Sin3A/histone deacetylase, and the ATAC/GNC5 acetyltransferase (10, 44, 45). In its role in regulation of the alphaherpesvirus IE genes during lytic infection, HCF-1 mediates the Set1/MLL1-dependent trimethylation of histone H3-lysine 4 of nucleosomes occupying the IE gene promoters, thus promoting the transcriptional induction of these genes (32). In addition, recent studies have also demonstrated that HCF-1 recruits the histone demethylase LSD1 to the IE gene regulatory domains, which is required to remove transcriptionally repressive histone H3-lysine 9 methylation (Y. Liang, A. Narayanan, J. L. Vogel, and T. M. Kristie, unpublished data). Failure to recruit HCF-1 or its associated modification components results in the accumulation of repressive chromatin across the viral IE gene promoters and inhibition of viral gene expression. Thus, HCF-1 is an essential control element of the viral lytic cycle. The recruitment by the viral IE activators (HSV-1 VP16, varicella-zoster virus IE62, or open reading frame 10) that are packaged in the viral tegument is a mechanism by which these viruses circumvent cell-directed repression of their genomes and promote the expression of their lytic IE genes.

While the initial characterization of HCF-1 focused on its role in viral gene expression, HCF-1 is now recognized as an essential cellular coactivator and mediates the activation potential of transcription factors of the ETS (GA-binding protein) (5, 40), E2F (17, 37), Krupple (Sp1 and Krox20) (11, 29, 31), and ATF/CREB (CREB3) families (8, 26, 28). Additionally, HCF-1 has multiple interactions with other coactivators (peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ coactivator [PGC], PGC-related coactivator, and FHL2) (24, 38, 39), regulates the expression of numerous cell targets involved in basic cellular processes (15), and is critical for cell cycle progression (9, 13, 14, 34), at least in part via its regulation of the E2F family members (37).

With respect to the role of HCF-1 in control of the alphaherpesvirus life cycle, the essential nature of the coactivator as well as the role of the protein in mediating chromatin modifications during lytic infection leads to a model in which HCF-1 might also play a significant role in the regulation of the viral latency in sensory neurons. The model is supported by the striking observation that, in contrast to other cell types, HCF-1 is uniquely sequestered in the cytoplasm of sensory neurons and is rapidly transported to the nucleus upon stimulation that promotes viral reactivation (21). However, the localization and, more specifically, the subcellular localization of HCF-1 in latently infected sensory neurons have not been determined. Therefore, in this study, the localization of HCF-1 was investigated in HSV-1 latently infected neurons of mouse trigeminal ganglia. The results show that similar to results with mock-infected ganglia, HCF-1 is specifically sequestered in the cytoplasm and is transported to the nucleus upon explant reactivation stimuli. In addition, development of a primary sensory neuronal cell culture system allowed for high-resolution delineation of the specific subcellular localization of this coactivator to the Golgi apparatus. The localization is distinct from that of the HCF-1 interaction partner CREB3 (luman/LZIP) (2, 35) and suggests that HCF-1 is sequestered via a neuronal specific Golgi apparatus-resident component.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Latently infected mice and trigeminal ganglia.

BALB/c mice, 6 to 8 weeks old, were anesthetized with avertin (30 to 80 mg/kg of body weight) and mock infected or infected with 5 × 105 PFU of HSV-1 (strain 17) per eye after corneal scarification. Latently infected mice were sacrificed 45 days postinfection, and trigeminal ganglia were rapidly removed. Latency establishment was confirmed by explantation of 6 trigeminal ganglia in culture. At 48 h postexplantation, trigeminal ganglia were homogenized, and the titer of the clarified supernatant was determined on Vero cells. For assessment of HCF-1 localization, trigeminal ganglia were either immediately fixed or incubated in complete medium (Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium, 10% fetal bovine serum, 2 mM glutamine) for various times prior to fixation. For immunohistochemistry (IHC) analysis, ganglia were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 12 h at 4°C and set in paraffin. For immunofluorescence (IF) assay, ganglia were quick-frozen in 22-oxyacalcitriol (Tissue-Tek; Sakura) on dry ice and cryo-sectioned. All animal care and handling were done in accordance with the NIH Animal Care and Use Guidelines and as noted in the approved animal protocol LVD40E.

Primary neuronal cell culture.

Fetal calf dorsal root ganglia (FC-DRG) were obtained from Pel-Freez Biologicals. Ganglia were trimmed to clean and remove fibers prior to incubation (0.5 ml/DRG) in Hanks balanced salt solution containing 3 mg/ml collagenase (Sigma) for 45 min at 37°C. Digested ganglia were washed three times in Hanks balanced salt solution and pelleted at 200 × g for 5 min, and the cells were dissociated by gentle trituration. Dissociated cells were pelleted at 80 × g for 5 min, and aliquots of approximately 106 cells were either plated or frozen in complete medium containing 10% (vol/vol) dimethyl sulfoxide in liquid nitrogen. Cells (105) were plated on 12-mm acid washed coverslips that were precoated for 2 h with 40 μg/ml poly-d-lysine and 4 μg/ml laminin (BD Bioscience). Cultures were incubated in growth medium (complete medium containing 100 ng/ml 2.5S nerve growth factor [NGF], 7.5 μg/ml fluoro-d-uridine, 10 μM uridine) at 35.5°C for 10 to 14 days. Growth medium was changed each day for 1 week and every 3 days thereafter. For brefeldin A treatment, cultured DRG neurons were incubated with or without 5 μg/ml brefeldin A (Sigma) for 2 h in complete medium at 35.5°C prior to fixation and staining for immunofluorescence.

IHC, IF, antibodies, and confocal microscopy.

IHC analysis was done using Histo-Stain-Plus or Super-Picture (Zymed) according to the manufacturer's recommendations and as previously described (21). For IF analysis, fixed cells were blocked in normal goat serum and incubated with primary antibodies for 2 h in 3% bovine serum albumin—phosphate buffered saline at 20°C, followed by secondary antibodies in normal goat serum for 1 h. Stained cells or sectioned ganglia were visualized using a Leica SP5 confocal microscope (Leica Microsystems) and LASAF software (version 2.182). Image reconstruction was done with Imaris (version 6.1; Bitplane AG). Images were cropped, and resolutions were adjusted in Photoshop, version 7.0. Antibodies used in this study were as follows: HCF-1, Ab2125 (19); a protein with a molecular weight of 58,000 (58K; Sigma G2404); GM130 (BD Bioscience G65120); calreticulin (Chemicon AB3409); RNA polymerase II (RNAP II; Covance MMS-126R); neurofilament 200 (Sigma N0142); CoxIV (Abcam ab14744); protein disulfide isomerase (PDI; Santa Cruz Biotechnology sc-59640); and KDEL (Stressgen SPA-827). Antigen affinity-purified CREB3 serum was a kind gift of R. Lu, University of Guelph, Ontario, Canada.

Cell fractionation.

Cultured DRG neurons were fractionated into soluble cytoplasmic and particulate fractions containing the cell nucleus and cytoplasmic membranes by centrifugation through an oil layer using a BioVision Cytosol/Particulate Rapid Separation Kit (K267) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. Total cell extract, soluble cytoplasm, and particulate fractions were resolved in a 4 to 20% polyacrylamide gel, transferred to Immobilon, and subjected to Western blotting with the primary antibodies indicated in Fig. 7.

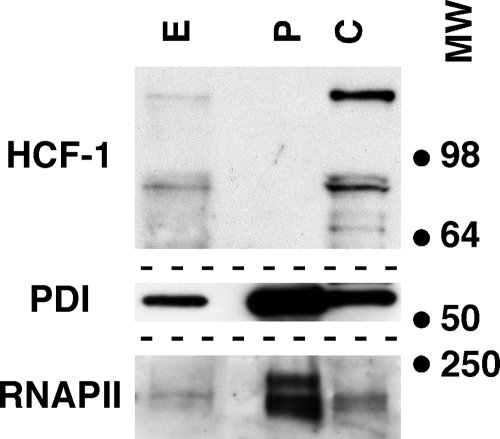

FIG. 7.

HCF-1 does not fractionate with the nucleus or cytoplasmic membranes of DRG neurons. Cultures of DRG neurons were fractionated as described in Materials and Methods into soluble cytoplasmic (C) and particulate (P) fractions containing the nucleus and cytoplasmic membranes. Fractions were resolved in 4 to 20% denaturing polyacrylamide gels and Western blotted using anti-HCF-1, anti-RNAP II, and anti-PDI antibodies. E, whole cell extract; MW, positions of molecular weight markers (in thousands).

RESULTS

HCF-1 localization and transport in latently infected neurons of sensory ganglia.

Previous studies have shown that in neurons of sensory ganglia of uninfected mice, HCF-1 is uniquely sequestered in the cytoplasm, in contrast to its nuclear localization in other mouse tissues. Stimuli such as ganglia explant or ocular scarification resulted in rapid relocalization of the protein to the nucleus in approximately 30% of the neurons (21). To determine the localization and transport of the protein in neurons of latently infected mice, animals were mock infected or infected with HSV-1. After the establishment of latency, the localization of HCF-1 was determined by IHC or IF staining. Ganglia were explanted and immediately fixed or were explanted for various times (1 h to 72 h) prior to fixation and staining (Fig. 1).

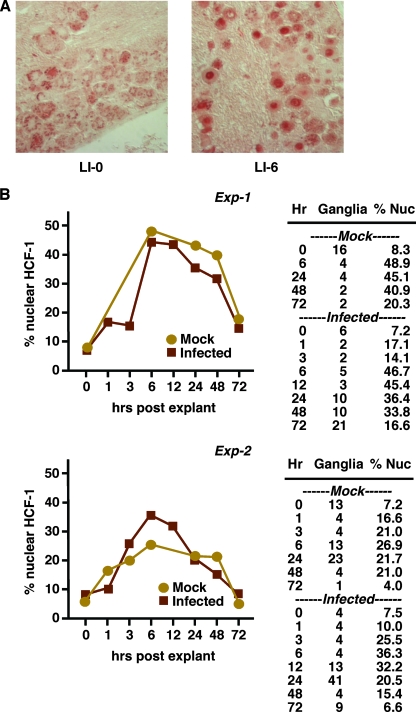

FIG. 1.

Localization and transport of HCF-1 in neurons of latently infected mice. (A) Trigeminal ganglia of mock-infected and latently infected mice were fixed, sectioned, and stained for HCF-1 at various times postexplantation (0 to 72 h). LI-0, latently infected and rapidly fixed; LI-6, latently infected and fixed at 6 h postexplantation. (B) The number of ganglia counted and the percentage of neurons exhibiting a nuclear accumulation (% Nuc) of HCF-1 are listed at the various times postexplantation. The results are graphically represented. Exp-1 and Exp-2 represent two independent time course experiments.

As shown in Fig. 1A, in neurons of latently infected ganglia that were immediately fixed postexplantation (left panel), HCF-1 is localized in punctate cytoplasmic structures. In contrast, explant incubation of ganglia results in rapid accumulation of HCF-1 in a large percentage of neurons by 6 h postexplantation (Fig. 1A, right panel). Figure 1B shows the results of two independent time course experiments in which both mock-infected and latently infected animals exhibit a predominantly cytoplasmic HCF-1 localization in unstimulated ganglia (∼7% of neurons exhibit nuclear HCF-1). Explant stimulation results in a rapid increase in the percentage of neurons exhibiting accumulation of nuclear HCF-1 with a peak at 6 to 12 h postexplantation (36 to 47%). This is followed by a slight decline in nuclear HCF-1 from 24 to 48 h and a return to the baseline cytoplasmic state by 72 h postexplantation. In both experiments, the percentage of neurons and the time frame duration of nuclear HCF-1 were similar. Most significantly, no difference between ganglia of mock-infected and HSV-1-infected animals was noted. Thus, latently infected animals exhibit HCF-1 localization and transport patterns similar to the patterns observed in mock-infected animals. Additionally, the time course of HCF-1 nuclear transport and nuclear accumulation correlates with that of viral reactivation from latency under these conditions.

Specific subcellular localization of HCF-1 in sensory neurons.

IHC staining of sensory ganglia shows a punctate cytoplasmic localization for HCF-1. To investigate the specific subcellular localization and provide a model for studies on the biochemistry of HCF-1 sequestering-transport, a primary neuronal cell culture system was developed. FC-DRG were chosen as the source of sensory neurons due to the availability and the more abundant neuronal yields relative to mouse trigeminal ganglia. Freshly dissected FC-DRG were dissociated, plated, and cultured in the presence of mitotic inhibitors, to reduce the nonneuronal population, and of NGF, to increase neuronal survival. As shown in Fig. 2, at 14 days postplating, the cultures exhibit a highly developed axonal network (left panel) as demonstrated by IF staining with anti-neurofilament 200 (right panel).

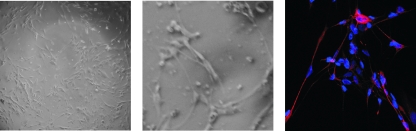

FIG. 2.

A DRG primary neuronal cell culture system. FC-DRG were dissociated and plated in the presence of NGF and mitotic inhibitors. After 14 days in culture, the neuronal network was visualized using bright-field microscopy or were stained with DAPI (4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole; blue) and anti-neurofilament (red) and visualized by confocal microscopy (right panel).

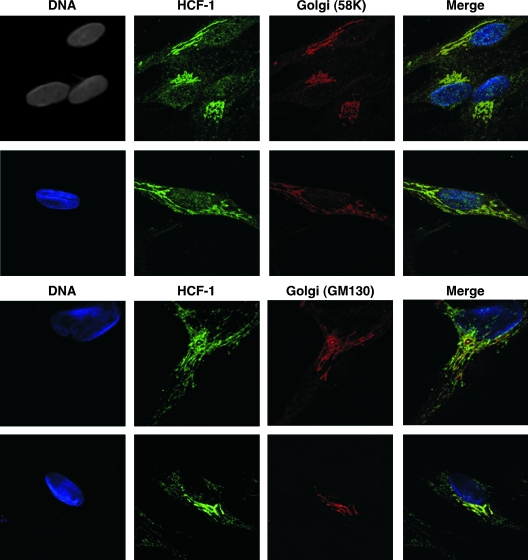

To determine the specific subcellular localization of HCF-1, mature cultures were costained for HCF-1 and selected subcellular markers and visualized by confocal microscopy. As shown in Fig. 3, HCF-1 exhibited the characteristic punctate localization pattern, often accumulating adjacent to the neuronal nucleus. No colocalization of HCF-1 and the nuclear (RNAP II), mitochondrial (CoxIV), or endoplasmic reticulum (ER-KDEL) markers was detected. This was of interest as one HCF-1 interacting partner, CREB3, an ER-resident protein, has been suggested to be involved in HCF-1 cytoplasmic sequestering (25). In contrast, HCF-1 exhibited a high degree of colocalization with two distinct Golgi apparatus markers (Fig. 4), 58K and GM130, indicating that the predominant pool of HCF-1 is sequestered either by specific transport of HCF-1 to the Golgi compartment or via association with a Golgi compartment-resident protein.

FIG. 3.

HCF-1 does not colocalize with nuclear, mitochondrial, or ER markers in unstimulated neurons. Cultures of DRG neurons were costained for HCF-1 (green), DNA (DAPI [4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole]; blue), and the indicated subcellular markers.

FIG. 4.

HCF-1 is localized at the Golgi apparatus in unstimulated DRG neurons. Cultures of DRG neurons were costained for HCF-1 (green), DNA (DAPI [4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole]; blue), and the 58K or GM130 Golgi apparatus markers.

Neuronal cultures faithfully reflect the in vivo localization of HCF-1.

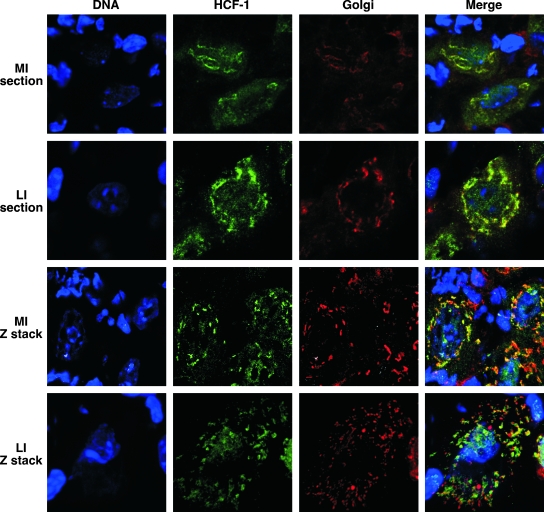

Accumulation of HCF-1 at the Golgi apparatus is unique and unexpected based upon the function of the protein as a transcriptional coactivator. To determine if this localization faithfully represented the localization of HCF-1 in neurons of sensory ganglia in vivo, trigeminal ganglia from mock-infected or latently infected mice were rapidly explanted, cryo-sectioned, and costained for HCF-1 and the Golgi apparatus 58K marker (Fig. 5). In both cases, HCF-1 specifically colocalized with this marker. The localization is further defined and confirmed by three-dimensional reconstruction of Z-stack images showing the characteristic punctation of HCF-1 and the Golgi apparatus marker 58K.

FIG. 5.

HCF-1 is localized at the Golgi apparatus in neurons of cryo-sectioned mouse trigeminal ganglia. Trigeminal ganglia of mock-infected (MI) or latently infected (LI) mice were rapidly explanted, snap-frozen, cryo-sectioned, and stained for HCF-1 (green), DNA (DAPI [4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole]; blue), and the Golgi apparatus (58K; red). Three-dimensional reconstructions of Z-stack sections are shown.

HCF-1 does not colocalize with CREB3 and translocates to the nucleus upon Golgi apparatus disruption.

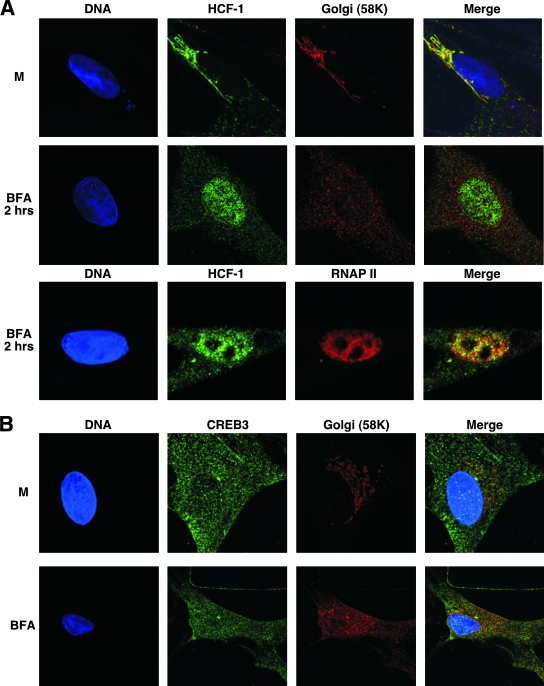

Disruption of the Golgi apparatus with brefeldin A results in the resorption of Golgi apparatus-resident proteins to the ER (16). As HCF-1 is apparently localized to the Golgi apparatus in unstimulated neurons, the impact of brefeldin A treatment was assessed in the primary neuronal cell culture system. As shown in Fig. 6A, treatment of these cells with brefeldin A for 2 h resulted in dispersal of the Golgi apparatus, as evidenced by the redistribution of the 58K marker. However, in contrast to this Golgi apparatus-resident protein, brefeldin A treatment resulted in nuclear accumulation of HCF-1 and colocalization with RNAP II. Thus, HCF-1 responds in a manner distinct from other Golgi apparatus-resident proteins.

FIG. 6.

Brefeldin A disruption of the Golgi apparatus results in nuclear accumulation of HCF-1. Cultures of DRG neurons were mock treated (M) or treated with brefeldin A (BFA) for 2 h, fixed, and stained for HCF-1 (A; green), CREB3 (B; green), DNA (DAPI [4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole]; blue), and Golgi apparatus (58K) or nuclear (RNAP II) markers.

As noted, HCF-1 interacts with numerous transcription factors and coactivators. Of these, the CREB family member CREB3 was originally isolated as a protein that bound HCF-1 via a small HCF-1 binding motif [(D/E)HXY] (8, 26, 27). CREB3 is an ER-resident transcription factor, tethered via a single transmembrane domain. Similar to other factors of this class such as ATF6 and the sterol regulatory element binding protein, the protein is activated by a multistep intramembrane proteolysis to release the amino-terminal domain that localizes to the nucleus and activates transcription (2-4, 6, 7, 12, 35, 36). Due to its cytoplasmic localization and high-affinity interaction with HCF-1, it has been proposed that CREB3 may be responsible for the unique neuronal cytoplasmic sequestering of HCF-1 (25). As shown in Fig. 6B, high-resolution IF staining of CREB3 in the sensory neuronal culture demonstrates that the protein is, as described, localized to the ER. However, there is no significant accumulation of the protein in the Golgi apparatus where HCF-1 localizes. In addition, treatment of the cultured neurons with brefeldin A has no apparent impact on the localization of CREB3, in contrast to the nuclear accumulation of HCF-1.

As HCF-1 has no apparent or identified transmembrane domain, it is likely that the protein is concentrated at the Golgi apparatus via binding to a Golgi apparatus-resident component(s). To investigate if HCF-1 would fractionate with the neuronal cell membranes, the cultured neurons were separated into soluble cytoplasmic and particulate fractions containing the cell nucleus and cytoplasmic membranes. As shown in Fig. 7, HCF-1 was detected exclusively in the cytoplasmic fraction whereas the ER (PDI) and nuclear (RNAP II) markers were found primarily in the particulate fraction. The results suggest that the association of HCF-1 with the Golgi apparatus is likely to be reflective of dissociable interactions with an as yet unidentified Golgi apparatus-resident component.

DISCUSSION

HCF-1 is an essential cellular coactivator for numerous transcription factors and other coactivators. The protein mediates the activation of the alphaherpesvirus IE genes through interactions with the IE activators (VP16, IE62, and open reading frame 10) of these viruses as well as cellular transcription factors/coactivators (GA-binding protein, Sp1, and FHL2) that impact the expression of the IE genes (18, 39). Despite the multiple factors and mechanisms that synergize to induce the high-level expression of these genes upon infection, depletion of HCF-1 abrogates both basal and induced IE gene expression (31).

At least one function of HCF-1 in this context involves coordinating removal of repressive chromatin marks with promoting activating marks on nucleosomes across the viral IE gene promoter-enhancer domains. A component of the Set1/MLL1 histone methyltransferase complex (44, 45), HCF-1 also recruits the histone demethylase LSD1 to remove cell-mediated repressive histone H3-lysine 9 methylation and promote activating histone H3-lysine 4 trimethylation (32; also Y. Liang et al., unpublished). Given the strict requirement for HCF-1, it is likely that this represents a common rate-limiting step for the activity of the various factors that mediate IE gene expression.

In addition to its role in stimulation of the IE genes during the lytic replication cycle, HCF-1 may also play a significant role in these viruses in the regulation of the lytic-latency-reactivation cycles in sensory neurons. Recent studies on the role of chromatin modulation of viral latency have shown that nucleosomal modifications at the promoter-enhancers of the latency-associated transcript and the viral IE genes are consistent with the states of activation and repression, respectively (1, 22, 23, 33, 41). Furthermore, induced reactivation results in the corresponding activating chromatin marks at the IE gene promoter domains, a role in which HCF-1 and its associated chromatin modification complexes may participate. This correlation, coupled with the original observation that HCF-1 is specifically and uniquely sequestered in the cytoplasm of unstimulated sensory neurons and is rapidly transported to the nucleus under conditions that result in viral reactivation, leads to a model in which activated nuclear transport of HCF-1 may be an important trigger in promoting viral reactivation.

Given the potential significance of HCF-1, the localization and transport of HCF-1 in latently infected sensory neurons were investigated. In these experiments, no significant difference was seen between mock-infected and latently infected animals with respect to the localization in unstimulated neurons. Similarly, no difference was seen in the percentage of neurons exhibiting nuclear HCF-1 accumulation poststimuli or the time course of the nuclear accumulation. In each case, the maximal number of neurons exhibiting nuclear HCF-1 peaked at 6 to 12 h postexplantation, and the nuclear localization was maintained to 48 h postexplantation. Interestingly, by 72 h postexplantation, HCF-1 was once more sequestered in the cytoplasm of the majority of neurons. It is interesting that this return to baseline may reflect an active process involving the HCF β-propeller interacting protein, an HCF-1 nuclear export factor (30).

Due to technical difficulties in assessing the subcellular localization of HCF-1 in explanted trigeminal ganglia by high-resolution IF assay, a primary cell culture system was developed. This system allowed for the specific localization of HCF-1 to the Golgi apparatus, a localization that was subsequently confirmed using cryo-sectioned ganglia. Localization or accumulation at the Golgi apparatus was not anticipated and represents a unique observation with respect to transcriptional coactivators. As HCF-1 is soluble and readily released upon cell disruption, it is unlikely that the protein is tightly bound to the membrane but, rather, is bound by another component that accumulates in or at the Golgi apparatus.

Importantly, HCF-1 does not substantially colocalize in the cytoplasm with CREB3, an HCF-1 interaction partner. This CREB family member is retained in the ER by a carboxy-terminal transmembrane domain and undergoes intramembrane proteolysis to release the amino-terminal transcription factor (35). The active factor is capable of stimulating transcription through some cis-acting replication elements (26). Given the interaction of CREB3 and HCF-1 and the ability of CREB3 in transfection experiments to activate the IE0 promoter, it was hypothesized that CREB3 might be responsible for sequestering HCF-1 (25). Activation of CREB3 processing would then result in cotransport of CREB3 and HCF-1 to the nucleus and activation of the target IE genes. However, the lack of substantial colocalization and the differential response to Golgi apparatus disruption suggest that CREB3 is not likely to be the primary component responsible for the HCF-1 cytoplasmic localization. The development of the primary neuronal cell culture system described here that faithfully reproduces the sequestered localization of HCF-1 may provide a more accessible system for the elucidation of the components and mechanism of the neuronal-specific sequestering and transport of this coactivator.

Acknowledgments

We thank R. Lu for CREB3 antiserum and N. Fraser for HSV-1 strain 17; J. Yewdell, C. Wilcox, A. Sears, and members of the Laboratory of Viral Diseases, Molecular Genetics Section, for helpful advice and discussions; O. Schwartz and members of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, Research Technology Branch, Microscopy Unit, for assistance with confocal microscopy; and T. Pierson, J. Vogel, Y. Liang, and A. McBride for critical reading of the manuscript.

These studies were supported by the Laboratory of Viral Diseases, Division of Intramural Research, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 30 July 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Amelio, A. L., N. V. Giordani, N. J. Kubat, J. E. O'Neil, and D. C. Bloom. 2006. Deacetylation of the herpes simplex virus type 1 latency-associated transcript (LAT) enhancer and a decrease in LAT abundance precede an increase in ICP0 transcriptional permissiveness at early times postexplant. J. Virol. 802063-2068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bailey, D., and P. O'Hare. 2007. Transmembrane bZIP transcription factors in ER stress signaling and the unfolded protein response. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 92305-2321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown, M. S., and J. L. Goldstein. 1997. The SREBP pathway: regulation of cholesterol metabolism by proteolysis of a membrane-bound transcription factor. Cell 89331-340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen, X., J. Shen, and R. Prywes. 2002. The luminal domain of ATF6 senses endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress and causes translocation of ATF6 from the ER to the Golgi. J. Biol. Chem. 27713045-13052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Delehouzee, S., T. Yoshikawa, C. Sawa, J. Sawada, T. Ito, M. Omori, T. Wada, Y. Yamaguchi, Y. Kabe, and H. Handa. 2005. GABP, HCF-1 and YY1 are involved in Rb gene expression during myogenesis. Genes Cells 10717-731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.DenBoer, L. M., P. W. Hardy-Smith, M. R. Hogan, G. P. Cockram, T. E. Audas, and R. Lu. 2005. Luman is capable of binding and activating transcription from the unfolded protein response element. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 331113-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ehrmann, M., and T. Clausen. 2004. Proteolysis as a regulatory mechanism. Annu. Rev. Genet. 38709-724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Freiman, R. N., and W. Herr. 1997. Viral mimicry: common mode of association with HCF by VP16 and the cellular protein LZIP. Genes Dev. 113122-3127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goto, H., S. Motomura, A. C. Wilson, R. N. Freiman, Y. Nakabeppu, K. Fukushima, M. Fujishima, W. Herr, and T. Nishimoto. 1997. A single-point mutation in HCF causes temperature-sensitive cell-cycle arrest and disrupts VP16 function. Genes Dev. 11726-737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guelman, S., T. Suganuma, L. Florens, S. K. Swanson, C. L. Kiesecker, T. Kusch, S. Anderson, J. R. Yates III, M. P. Washburn, S. M. Abmayr, and J. L. Workman. 2006. Host cell factor and an uncharacterized SANT domain protein are stable components of ATAC, a novel dAda2A/dGcn5-containing histone acetyltransferase complex in Drosophila. Mol. Cell. Biol. 26871-882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gunther, M., M. Laithier, and O. Brison. 2000. A set of proteins interacting with transcription factor Sp1 identified in a two-hybrid screening. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 210131-142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoppe, T., M. Rape, and S. Jentsch. 2001. Membrane-bound transcription factors: regulated release by RIP or RUP. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 13344-348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Julien, E., and W. Herr. 2004. A switch in mitotic histone H4 lysine 20 methylation status is linked to M phase defects upon loss of HCF-1. Mol. Cell 14713-725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Julien, E., and W. Herr. 2003. Proteolytic processing is necessary to separate and ensure proper cell growth and cytokinesis functions of HCF-1. EMBO J. 222360-2369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khurana, B., and T. M. Kristie. 2004. A protein sequestering system reveals control of cellular programs by the transcriptional coactivator HCF-1. J. Biol. Chem. 27933673-33683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Klausner, R. D., J. G. Donaldson, and J. Lippincott-Schwartz. 1992. Brefeldin A: insights into the control of membrane traffic and organelle structure. J. Cell Biol. 1161071-1080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Knez, J., D. Piluso, P. Bilan, and J. P. Capone. 2006. Host cell factor-1 and E2F4 interact via multiple determinants in each protein. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 28879-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kristie, T. M. 2007. Early events pre-initiation of alphaherpesvirus viral gene expression, p. 112-127. In A. Arvin, G. Campadelli-Fiume, E. Mocarski, P. S. Moore, B. Roizman, R. Whitley, and K. Yamanishi (ed.), Human herpesviruses biology, therapy, and immunoprophylaxis. Cambridge University Press, New York, NY. [PubMed]

- 19.Kristie, T. M., J. L. Pomerantz, T. C. Twomey, S. A. Parent, and P. A. Sharp. 1995. The cellular C1 factor of the herpes simplex virus enhancer complex is a family of polypeptides. J. Biol. Chem. 2704387-4394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kristie, T. M., and P. A. Sharp. 1993. Purification of the cellular C1 factor required for the stable recognition of the Oct-1 homeodomain by the herpes simplex virus alpha-trans-induction factor (VP16). J. Biol. Chem. 2686525-6534. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kristie, T. M., J. L. Vogel, and A. E. Sears. 1999. Nuclear localization of the C1 factor (host cell factor) in sensory neurons correlates with reactivation of herpes simplex virus from latency. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 961229-1233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kubat, N. J., A. L. Amelio, N. V. Giordani, and D. C. Bloom. 2004. The herpes simplex virus type 1 latency-associated transcript (LAT) enhancer/rcr is hyperacetylated during latency independently of LAT transcription. J. Virol. 7812508-12518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kubat, N. J., R. K. Tran, P. McAnany, and D. C. Bloom. 2004. Specific histone tail modification and not DNA methylation is a determinant of herpes simplex virus type 1 latent gene expression. J. Virol. 781139-1149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lin, J., P. Puigserver, J. Donovan, P. Tarr, and B. M. Spiegelman. 2002. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1β (PGC-1β), a novel PGC-1-related transcription coactivator associated with host cell factor. J. Biol. Chem. 2771645-1648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lu, R., and V. Misra. 2000. Potential role for luman, the cellular homologue of herpes simplex virus VP16 (α gene trans-inducing factor), in herpesvirus latency. J. Virol. 74934-943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lu, R., P. Yang, P. O'Hare, and V. Misra. 1997. Luman, a new member of the CREB/ATF family, binds to herpes simplex virus VP16-associated host cellular factor. Mol. Cell. Biol. 175117-5126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lu, R., P. Yang, S. Padmakumar, and V. Misra. 1998. The herpesvirus transactivator VP16 mimics a human basic domain leucine zipper protein, luman, in its interaction with HCF. J. Virol. 726291-6297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Luciano, R. L., and A. C. Wilson. 2002. An activation domain in the C-terminal subunit of HCF-1 is important for transactivation by VP16 and LZIP. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 9913403-13408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Luciano, R. L., and A. C. Wilson. 2003. HCF-1 functions as a coactivator for the zinc finger protein Krox20. J. Biol. Chem. 27851116-51124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mahajan, S. S., M. M. Little, R. Vazquez, and A. C. Wilson. 2002. Interaction of HCF-1 with a cellular nuclear export factor. J. Biol. Chem. 27744292-44299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Narayanan, A., M. L. Nogueira, W. T. Ruyechan, and T. M. Kristie. 2005. Combinatorial transcription of herpes simplex virus and varicella zoster virus immediate early genes is strictly determined by the cellular coactivator HCF-1. J. Biol. Chem. 2801369-1375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Narayanan, A., W. T. Ruyechan, and T. M. Kristie. 2007. The coactivator host cell factor-1 mediates Set1 and MLL1 H3K4 trimethylation at herpesvirus immediate early promoters for initiation of infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 10410835-10840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Neumann, D. M., P. S. Bhattacharjee, N. V. Giordani, D. C. Bloom, and J. M. Hill. 2007. In vivo changes in the patterns of chromatin structure associated with the latent herpes simplex virus type 1 genome in mouse trigeminal ganglia can be detected at early times after butyrate treatment. J. Virol. 8113248-13253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Piluso, D., P. Bilan, and J. P. Capone. 2002. Host cell factor-1 interacts with and antagonizes transactivation by the cell cycle regulatory factor Miz-1. J. Biol. Chem. 27746799-46808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Raggo, C., N. Rapin, J. Stirling, P. Gobeil, E. Smith-Windsor, P. O'Hare, and V. Misra. 2002. Luman, the cellular counterpart of herpes simplex virus VP16, is processed by regulated intramembrane proteolysis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 225639-5649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stirling, J., and P. O'Hare. 2006. CREB4, a transmembrane bZip transcription factor and potential new substrate for regulation and cleavage by S1P. Mol. Biol. Cell 17413-426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tyagi, S., A. L. Chabes, J. Wysocka, and W. Herr. 2007. E2F activation of S phase promoters via association with HCF-1 and the MLL family of histone H3K4 methyltransferases. Mol. Cell 27107-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vercauteren, K., N. Gleyzer, and R. C. Scarpulla. 2008. PGC-1-related coactivator complexes with HCF-1 and NRF-2β in mediating NRF-2(GABP)-dependent respiratory gene expression. J. Biol. Chem. 28312102-12111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vogel, J. L., and T. M. Kristie. 2006. Site-specific proteolysis of the transcriptional coactivator HCF-1 can regulate its interaction with protein cofactors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1036817-6822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vogel, J. L., and T. M. Kristie. 2000. The novel coactivator C1 (HCF) coordinates multiprotein enhancer formation and mediates transcription activation by GABP. EMBO J. 19683-690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang, Q. Y., C. Zhou, K. E. Johnson, R. C. Colgrove, D. M. Coen, and D. M. Knipe. 2005. Herpesviral latency-associated transcript gene promotes assembly of heterochromatin on viral lytic-gene promoters in latent infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 10216055-16059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wilson, A. C., M. A. Cleary, J. S. Lai, K. LaMarco, M. G. Peterson, and W. Herr. 1993. Combinatorial control of transcription: the herpes simplex virus VP16-induced complex. Cold Spring Harbor Symp. Quant. Biol. 58167-178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wilson, A. C., K. LaMarco, M. G. Peterson, and W. Herr. 1993. The VP16 accessory protein HCF is a family of polypeptides processed from a large precursor protein. Cell 74115-125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wysocka, J., M. P. Myers, C. D. Laherty, R. N. Eisenman, and W. Herr. 2003. Human Sin3 deacetylase and trithorax-related Set1/Ash2 histone H3-K4 methyltransferase are tethered together selectively by the cell-proliferation factor HCF-1. Genes Dev. 17896-911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yokoyama, A., Z. Wang, J. Wysocka, M. Sanyal, D. J. Aufiero, I. Kitabayashi, W. Herr, and M. L. Cleary. 2004. Leukemia proto-oncoprotein MLL forms a SET1-like histone methyltransferase complex with menin to regulate Hox gene expression. Mol. Cell. Biol. 245639-5649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]