Abstract

We investigated the distribution and activity of chloroethene-degrading microorganisms and associated functional genes during reductive dehalogenation of tetrachloroethene to ethene in a laboratory continuous-flow column. Using real-time PCR, we quantified “Dehalococcoides” species 16S rRNA and chloroethene-reductive dehalogenase (RDase) genes (pceA, tceA, vcrA, and bvcA) in nucleic acid extracts from different sections of the column. Dehalococcoides 16S rRNA gene copies were highest at the inflow port [(3.6 ± 0.6) × 106 (mean ± standard deviation) per gram soil] where the electron donor and acceptor were introduced into the column. The highest transcript numbers for tceA, vcrA, and bvcA were detected 5 to 10 cm from the column inflow. bvcA was the most highly expressed of all RDase genes and the only vinyl chloride reductase-encoding transcript detectable close to the column outflow. Interestingly, no expression of pceA was detected in the column, despite the presence of the genes in the microbial community throughout the column. By comparing the 16S rRNA gene copy numbers to the sum of all four RDase genes, we found that 50% of the Dehalococcoides population in the first part of the column did not contain either one of the known chloroethene RDase genes. Analysis of 16S rRNA gene clone libraries from both ends of the flow column revealed a microbial community dominated by members of Firmicutes and Actinobacteria. Higher clone sequence diversity was observed near the column outflow. The results presented have implications for our understanding of the ecophysiology of reductively dehalogenating Dehalococcoides spp. and their role in bioremediation of chloroethenes.

Tetrachloroethene (PCE) and trichloroethene (TCE) are the most-abundant groundwater contaminants in the United States (32). In situ bioremediation is a promising technology for the removal of these chlorinated solvents from contaminated aquifers (6, 23, 29). Of particular interest for bioremediation are microorganisms of the genus “Dehalococcoides” (1, 7, 10, 11, 13, 15, 31). In addition to other recalcitrant chloroorganic pollutants, Dehalococcoides spp. reductively dechlorinate PCE, TCE, cis-dichloroethene (cDCE), and vinyl chloride (VC) to ethene. While some microbial species other than Dehalococcoides spp. degrade chlorinated solvents, reductive dechlorination of PCE past cDCE has been linked exclusively to members of the genus Dehalococcoides (11, 31, 36, 45).

The reduction of chloroethenes by Dehalococcoides spp. is mediated by reductive dehalogenase (RDase) enzymes. While many RDase genes have been identified, only a few have been characterized for their function. Known RDase genes involved in chloroethene reduction are pceA, encoding PCE reductases from Dehalococcoides ethenogenes strain 195 (DET0318; GenBank accession no. NC_002936) (28) and Dehalococcoides sp. strain CBDB1 (cbdB_A1588; GenBank accession no. NC_007356) (8); tceA, encoding TCE reductases from D. ethenogenes strain 195 (DET0079; GenBank accession no. NC_002936) (27) and Dehalococcoides sp. strain FL2 (GenBank accession no. AY165309) (10); vcrA, encoding the VC reductase from Dehalococcoides sp. strain VS (GenBank accession no. AY322364) (36); and bvcA, encoding the VC reductase from Dehalococcoides sp. strain BAV1 (DehaBAV1_0847; GenBank accession no. NC_009455) (18). Little is known about the distribution and activity of Dehalococcoides spp. and their RDase genes under PCE-dechlorinating conditions in contaminated aquifers. The detection and quantification of RDase genes can provide information about the abundance, metabolic capabilities, and activity of Dehalococcoides spp. in cultures and environmental samples. In previous studies, RDase gene quantification has been used to assess the physiology of Dehalococcoides spp. in laboratory cultures, environmental enrichments, and contaminated groundwater (12, 21, 22, 41, 45).

We quantified the known chloroethene RDase genes in DNA and RNA extractions from aquifer solids of a PCE-dechlorinating continuous-flow column. The Dehalococcoides species 16S rRNA gene served as the phylogenetic gene marker to determine Dehalococcoides species cell numbers. The laboratory-scale flow column contained aquifer solids from the Hanford contaminated-field site (Richland, WA) and was bioaugmented with the Evanite culture, a Dehalococcoides species enrichment culture (3). The dechlorinating capacity of the Evanite culture has previously been characterized in batch kinetics studies (49, 50). We analyzed the abundance, distribution, and gene expression of Dehalococcoides spp. and their known chloroethene RDase genes in a bioaugmented, aquifer condition-simulating flow column which completely transformed PCE to ethene at the point of sampling. The study addresses the complex interplay of Dehalococcoides species population structure and activity under modeled aquifer conditions and is intended to add to our understanding of the ecophysiology and role of Dehalococcoides spp. in the environmental cleanup of chlorinated ethenes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Column assembly, operation, and sampling.

The experimental design, column construction, and performance, as well as chloroethene transformation rates, are described elsewhere (3). The column was bioaugmented with a Dehalococcoides species enrichment culture (Evanite) for which transformation rate kinetics for the complete dechlorination of PCE have been studied in detail previously (49, 50). The column was operated for 170 days before aquifer solids were sampled for nucleic acid extraction. Samples for nucleic acid extractions were taken from six sections of the 30-cm-long column under anoxic conditions in a glove box (90% N2, 10% H2 atmosphere). The following intervals were collected: 0 to 5 cm, 5 to 10 cm, 10 to 15 cm, 15 to 20 cm, 20 to 25 cm, and 25 to 30 cm. The 0- to 5-cm section was closest to the column influent port. The 25- to 30-cm section at the opposite end of the column was next to the column effluent port. The total aquifer solids of each section were sampled with an autoclaved spatula. The column solids were placed in a separate autoclaved sample container and homogenized before aliquots for storage were prepared. For DNA extraction, 20-g amounts of aquifer solids were placed in 50-ml polypropylene tubes and stored at −20°C. For RNA extraction, aquifer solids (20 g) were mixed with equal volumes of RNA stabilization solution (RNAlater; Ambion, Inc.), immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C.

Primer design for real-time PCR.

The program Primer3 (42) was used to design real-time PCR primers that target the 16S rRNA gene of Dehalococcoides spp.; the vcrA gene of Dehalococcoides sp. strain VS (GenBank accession no. AY322364); the bvcA gene of Dehalococcoides sp. strain BAV1 (GenBank accession no. AY563562); the tceA genes of D. ethenogenes strain 195 (GenBank accession no. AF228507) and Dehalococcoides sp. strain FL2 (GenBank accession no. AY165309); and the pceA genes of D. ethenogenes strain 195 (DET0318; GeneID 3230306 and GenBank accession no. NC_002936) and strain CBDB1 (cbdB_A1588; GeneID 3623470 and GenBank accession no. NC_007356). The primers for the pceA gene in D. ethenogenes strain 195 and strain CBDB1 also target a putative gene producing an RDase homologue in Dehalococcoides sp. strain VS (locus tag DeVSDRAFT_827; GenBank accession no. ABFQ01000002). The amplicon lengths ranged from 139 to 306 bp. Primer specificity was confirmed with the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/blast) and by comparison with the genome sequences of Dehalococcoides sp. strain VS (draft sequence GenBank accession no. ABFQ00000000), Dehalococcoides sp. strain CBDB1 (19), Dehalococcoides sp. strain BAV1 (GenBank accession no. NC_009455), and D. ethenogenes strain 195 (43). Primer specificity was also confirmed by PCR with genomic DNA of Dehalococcoides species cultures, including strains VS, FL2, BAV1, CBDB1, and 195 and the Evanite enrichment culture. The specificity of the Dehalococcoides species 16S rRNA gene primers was further evaluated by performing PCR amplification of the cloned 16S rRNA gene sequences from the 16S rRNA gene clone libraries that were constructed from the 0- to 5-cm and 25- to 30-cm sections of the column. The primers failed to amplify all non-Dehalococcoides 16S rRNA gene sequences obtained from the column, while they successfully amplified positive Dehalococcoides species clones from pure cultures. The universal bacterial 16S rRNA gene primers were those of Muyzer et al. (37). The primers for Dehalobacter sp. and Desulfitobacterium spp. were those of Smits et al. (44). All primers used in this study are summarized in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Oligonucleotides used for real-time PCR

| Name | Sequence (5′→3′) | Positiona | Product size (bp) | Target organism(s); gene(s) | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eub341F | CCTACGGGAGGCAGCAG | 341-357 | 194 | Bacteria; 16S rRNA genes | 37 |

| Eub534R | ATTACCGCGGCTGCTGGC | 534-517 | Bacteria; 16S rRNA genes | 37 | |

| Dehalo505F | GGCGTAAAGTGAGCGTAG | 505-522 | 199 | Dehalococcoides spp.; 16S rRNA genes | This study |

| Dehalo686R | GACAACCTAGAAAACCGC | 703-686 | Dehalococcoides spp.; 16S rRNA genes | This study | |

| Dre441F | GTTAGGGAAGAACGGCATCTGT | 441-461 | 227 | Dehalobacter spp.; 16S rRNA genes | 44 |

| Dre645R | CCTCTCCTGTCCTCAAGCCATA | 645-666 | Dehalobacter spp.; 16S rRNA genes | 44 | |

| Dsb406F | GTACGACGAAGGCCTTCGGGT | 406-426 | 225 | Desulfitobacterium spp.; 16S rRNA genes | 44 |

| Dsb619R | CCCAGGGTTGAGCCCTAGGT | 610-619 | Desulfitobacterium spp.; 16S rRNA genes | 44 | |

| vcrA880F | CCCTCCAGATGCTCCCTTTA | 880-899 | 139 | Dehalococcoides sp. strain VS; vcrA | This study |

| vcrA1018R | ATCCCCTCTCCCGTGTAACC | 999-1018 | Dehalococcoides sp. strain VS; vcrA | This study | |

| bvcA277F | TGGGGACCTGTACCTGAAAA | 277-296 | 247 | Dehalococcoides sp. strain BAV-1; bvcA | This study |

| bvcA523R | CAAGACGCATTGTGGACATC | 504-523 | Dehalococcoides sp. strain BAV-1; bvcA | This study | |

| tceA511F | GCCACGAATGGCTCACATA | 511-529 | 306 | D. ethenogenes strain 195 and Dehalococcoides sp. strain FL2; tceA | This study |

| tceA817R | TAATCGTATACCAAGGCCCG | 798-817 | D. ethenogenes strain 195 and Dehalococcoides sp. strain FL2; tceA | This study | |

| pceA877F | ACCGAAACCAGTTACGAACG | 877-896 | 100 | D. ethenogenes strain 195, Dehalococcoides sp. strain CBDB1, and Dehalococcoides sp. strain VS; pceA homologs | This study |

| pceA976R | GACTATTGTTGCCGGCACTT | 957-976 | D. ethenogenes strain 195, Dehalococcoides sp. strain CBDB1, and Dehalococcoides sp. strain VS; pceA homologs | This study |

For the 16S rRNA gene primer, the position numbering corresponds to the relative position in the E. coli 16S rRNA gene. The position numbers of the gene-specific primers correspond to positions within the genes of the listed organisms.

DNA and RNA extraction.

Total DNA from the Dehalococcoides species cultures and the column soil was prepared as follows: 0.5 ml of culture or 0.5 g of soil were mixed with 0.25 ml of 1× TE buffer (100 mM Tris-HCl, 100 mM EDTA, pH 8.0). A spatula tip of acid-washed glass beads (0.1 to 0.15 μm in diameter; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) and sodium dodecyl sulfate to a final concentration of 2% were added to the sample. The samples were vortexed briefly and incubated in boiling water for 2 min. Subsequently, the samples were frozen in liquid nitrogen and kept on ice until they were completely thawed. The thawed samples were amended with 50 μl of a 10% bovine serum albumin solution and vortexed for 10 min. After centrifugation at 4°C for 3 min at 12,000 × g, 0.43 ml extraction buffer (0.8 M NaCl, 500 mM Na acetate, pH 5.5) was added to each sample. The samples were split, and DNA was extracted at least twice with 1.5 volumes of phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1, vol/vol/vol, pH 8.0; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) in 2-ml phase-lock tubes (heavy gel; Eppendorf, Westbury, NY). After the final centrifugation (5 min at 13,200 × g), DNA in the aqueous phase was precipitated with 2.5 volumes of absolute ethanol at −20°C for at least 2 h. The precipitated DNA was collected by centrifugation for 30 min at 13,200 × g at 4°C. DNA pellets were washed in 75% ethanol, centrifuged, and dried for 15 min at room temperature. DNA was dissolved overnight at 4°C in 20 μl nuclease-free water. Aliquots of split samples were combined (final volume, 40 μl) and stored at −20°C.

Total RNA was isolated following the hot phenol-chloroform extraction protocol of Oelmüller et al. (38). All solutions were treated with 0.1% (vol/vol) diethylpyrocarbonate (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) and subsequently autoclaved prior to use. RNA was dissolved in 20 μl RNase-free water and additionally purified from humic substances by using the RNA cleanup spin columns from a Fast RNA Pro soil-direct kit (MP Biomedicals, Solon, OH). Residual DNA was removed by incubation with 5 U RNase-free DNase (1 U/μl; Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN) in DNase buffer (40 mM Tris-HCl, 10 mM NaCl, 6 mM MgCl2, and 10 mM CaCl2, pH 8.0) in a total volume of 100 μl. Following DNA digestion, RNA was purified with an RNeasy MinElute cleanup kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) by following the manufacturer's instructions. Finally, RNA was eluted in 15 μl RNase-free water, and aliquots were stored at −80°C.

Using SuperScript III reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), cDNA synthesis from total RNA was carried out by following the manufacturer's instructions. To test for the absence of residual DNA contamination in the cDNA preparations, we performed reverse transcription control reactions lacking reverse transcriptase enzyme. No PCR amplicons could be obtained from any sample when reverse transcriptase was omitted from reverse transcription reactions.

Construction and application of plasmid standard for real-time PCR.

A plasmid (pCR2.1_rdh16S) containing fragments of five different genes was assembled. The plasmid contained fragments of four RDase genes and a fragment of a 16S rRNA gene of Dehalococcoides spp., similar to the plasmid standard described by Holmes et al. (12). The 16S rRNA gene and vcrA were amplified and cloned from Dehalococcoides sp. strain VS genomic DNA (36), tceA and pceA were amplified and cloned using genomic DNA from D. ethenogenes strain 195 (31), and bvcA was amplified and cloned from DNA of Dehalococcoides sp. strain BAV1 (11). A detailed description of how the plasmid standard was constructed, including a list of primers, is given in the supplemental material. The sequences and orientation of the five gene fragments in plasmid pCR2.1_rdh16S were verified by DNA sequencing. The concentration of pCR2.1_rdh16S was determined by using a Qubit fluorometer and a Quant-iT double-stranded DNA broad-range assay kit according to the manufacturer's protocol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA).

Real-time PCR and data analysis.

The absolute quantification of genes and transcripts in the aquifer solids from the continuous-flow bioreactor was performed by using iQ Sybr green supermix (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) and gene-specific primers for different RDases (Table 1). Each sample mixture had a 30-μl reaction volume containing 1× iQ Sybr green supermix, forward and reverse primers at a concentration of 500 nM, and 6 or 2 μl of the prepared DNA or cDNA, respectively. PCR amplification and detection were conducted in an iCycler (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). Real-time PCR conditions were as follows: 3 min at 95°C followed by 40 cycles of 10 s at 95°C and 45 s at 61.5°C.

For real-time PCR data analysis, the raw data with background subtracted were exported from the iCycler system and analyzed by using Real-Time PCR Miner software (51). The algorithm calculates the efficiency (E) and threshold cycle (CT) based on the kinetics results of individual real-time PCRs. The start template concentration (N) per reaction mixture was calculated with the equation

|

(1) |

Calibration curves (log gene copy number per reaction volume versus log N) were obtained by using serial dilutions of plasmid pCR2.1_rdh16S. Equations 2 and 3 were used to calculate the number of gene copies in a known amount of plasmid DNA.

|

(2) |

|

(3) |

The molecular size of plasmid pCR2.1_rdh16S was determined to be 3.86 × 106 g mol−1. The number of gene copies per reaction volume was calculated by using the corresponding gene's standard curve for pCR2.1_rdh16S. Slopes and y intercepts of standard curves were determined by regression analysis in Excel (Microsoft Office 2003) and used to calculate the number of gene copies per reaction volume based on log N. The number of target genes per volume of sample was determined with equation 4. The value obtained for the number of target gene copies per reaction volume was multiplied by the volume of DNA (40 μl) or RNA (15 μl) extracted from each sample and divided by both the number of μl of DNA (6 μl) and the amount of RNA (2 μl cDNA = 1 μl RNA) used per reaction mixture and the volume of sample from which the DNA was extracted.

|

(4) |

Each real-time PCR (primer/template combination) was performed in triplicate, and triplicate measurements were repeated twice on independent nucleic acid extractions. The error bars shown in the figures represent the averages and standard deviations of the results of six real-time PCRs per sample. To verify the amplification of a single product and correct amplicon size, melting curve analysis was performed. Additionally, aliquots of the amplified product were examined by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis.

Clone library construction and sequencing.

16S rRNA gene libraries were constructed from column aquifer material sampled close to the inflow (0 to 5 cm) and outflow ports (25 to 30 cm) of the flow column. DNA was extracted as described above. Domain-specific primers were used to amplify almost-full-length 16S rRNA genes from the extracted chromosomal DNAs by PCR; for Bacteria, primers GM3F (Escherichia coli 16S rRNA position 0008) (37) and Uni1392R (20) were used, and for Archaea, primers 20f (30) and Uni1392R or 20f and Arch958R (4) were used. PCRs were performed as follows. Amplifications were carried out in 50-μl volumes containing a final concentration of 0.5 μM of each primer, 200 μM of each deoxynucleoside triphosphate, 0.5 U of Taq polymerase (Qiagen GmbH, Germany), 200 μg bovine serum albumin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), and 1× Qiagen PCR buffer containing 1.5 mM MgCl2 (pH 8.0). One-microliter amounts of the undiluted and 1:10-, 1:100-, and 1:1,000-diluted environmental DNA were used as template. The PCR amplification parameters included an initial denaturation at 94°C for 5 min, followed by 25 cycles of 94°C for 1 min, 48°C for 1 min using the Bacteria domain-specific primers, and 58°C for 1 min using the Archaea domain-specific primers, followed by an elongation step at 72°C for 1 min. The last cycle was followed by a final extension step at 72°C for 9 min. PCR amplifications were performed in a PTC-200 gradient cycler (MJ Research, Inc., Watertown, MA). The PCR products were purified by using a QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen GmbH, Germany) and ligated into the pCR4 TOPO vector (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). E. coli XL10-Gold ultracompetent cells (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) were transformed with the plasmids according to the manufacturer's recommendations.

Sequencing was performed by MCLab (South San Francisco, CA) by using Taq cycle sequencing with a model ABI 3730XL sequencer (Applied Biosystems). Sequence assembly was done with the program DNA Baser. The presence of chimeric sequences in the clone libraries was determined with the programs Bellerophon and Mallard version 1.02 (2, 14). Potential chimeras were eliminated before phylogenetic analysis. Sequence data were analyzed with BLAST and the ARB software package using the SILVA database (release date, 18 July 2007) (25, 39).

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The 16S rRNA gene sequences from this study have been submitted to EMBL and assigned accession numbers FM178517 to FM178533 (inflow) and FM178802 to FM178834 (outflow).

RESULTS

Column operation, performance, and chloroethene transformation rates.

The column operation conditions, performance, and chloroethene transformation rates were reported in a paper by Azizian et al. (3). Here we provide a brief summary of the results of the preceding study. In the flow column experiment, a PCE influent concentration of 0.09 mM was transformed to VC and ethene within a hydraulic residence time of 1.3 days. PCE dechlorination to cDCE was observed after bioaugmentation with the Evanite enrichment culture and following an increase in lactate concentration from 0.35 to 0.67 mM. Further increase in the lactate concentration to 1.34 mM resulted in the complete reduction of cDCE to VC and ethene. PCE and VC transformation rates were determined in batch-incubated microcosms constructed with aquifer soil from the column. In the first 5 cm from the column inlet, the PCE transformation rates were highest, and they decreased toward the column effluent. Dehalococcoides spp. accounted for up to 4% of the total Bacteria community in the flow column, which was consistent with estimates of electron donor utilization (4%) for dechlorination reactions (3).

Evaluation of the quantitative real-time PCR with axenic and mixed Dehalococcoides species cultures.

Real-time PCR was used to quantify the copy numbers of vcrA, bvcA, tceA, pceA, and Dehalococcoides species 16S rRNA genes for D. ethenogenes strain 195 and Dehalococcoides sp. strains VS, CBDB1, BAV1, and FL2 and the Evanite enrichment culture. There is only a single 16S rRNA gene copy and single copies of multiple genes producing RDase homologues in each of the four sequenced Dehalococcoides genomes (D. ethenogenes strain 195 [43]; Dehalococcoides sp. strain CBDB1 [19]; Dehalococcoides sp. strain VS [draft sequence GenBank accession no. ABFQ00000000]; and Dehalococcoides sp. strain BAV1 [GenBank sequence accession no. NC_009455]). To accurately reflect this stoichiometry, we constructed and used for quantification a plasmid standard that contains fragments of the four RDase genes and a 16S rRNA gene of Dehalococcoides spp. (pCR2.1_rdh16S). Standard curves generated with pCR2.1_rdh16S showed a 1:1 ratio of the RDase gene copy numbers to the 16S rRNA gene copy number (r2 = 0.99) (data not shown). Our real-time PCR method was linear over a dynamic range of 101 to 107 gene copies per μl of template solution. The detection limit of Dehalococcoides species 16S rRNA genes and RDase genes was 1 × 104 copies per ml or gram, respectively.

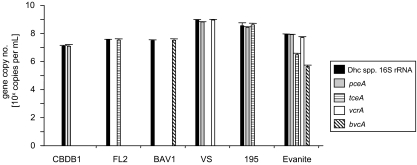

Quantification of gene copy numbers in genomic DNA obtained from axenic cultures of Dehalococcoides sp. strains CBDB1, FL2, BAV1, VS, and 195, respectively, confirmed that the RDase gene copy numbers matched the 16S rRNA gene copy number within 8% (Fig. 1). This result is consistent with Dehalococcoides sp. strains CBDB1, FL2, and BAV1 carrying a single copy of either the pceA, tceA, or bvcA gene. D. ethenogenes strain 195 contains single copies of pceA and tceA RDase genes. Dehalococcoides sp. strain VS carries a single copy of the vcrA gene and also contains a gene producing an RDase that is homologous to the PCE reductase in strain 195, whose function is not yet characterized (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

RDase and 16S rRNA gene copy numbers of pure and enrichment cultures of Dehalococcoides spp. determined by real-time PCR. The graph shows the results for five Dehalococcoides sp. pure cultures (strains CBDB1, FL2, BAV1, VS, and 195) and one enrichment culture (Evanite). Each bar represents the average of the results of triplicate real-time PCRs performed on two independent DNA extractions (n = 6). Dhc, Dehalococcoides.

The Evanite culture was used to inoculate the flow column. It is a mixed microbial enrichment culture that contains Dehalococcoides spp. which have not been characterized for their RDase gene composition. Thus, we quantified the Dehalococcoides species 16S rRNA and chloroethene RDase gene composition of the Evanite culture prior to column inoculation. The Dehalococcoides species 16S rRNA gene copy number of the Evanite culture was 8.5 × 107 ± 0.7 × 107 (mean ± standard deviation) per ml. The most-abundant RDase gene was found to be pceA (8.4 × 107 ± 3.8 × 106 copies per ml), present in 98% of the Dehalococcoides species cells in the culture, as determined by the fraction of RDase gene and 16S rRNA gene copy numbers. The vcrA gene was present in 60% (5.1 × 107 ± 8.1 × 106 copies per ml) of all Dehalococcoides species cells in the Evanite culture. tceA-containing Dehalococcoides species cells represented 4% (3.0 × 106 ± 0.8 × 106 copies per ml) and bvcA-containing Dehalococcoides spp. cells represented 1% (4.5 × 105 ± 1.0 × 105 copies per ml) of the total Dehalococcoides species population. This shows that the Evanite enrichment culture contains a diverse population of Dehalococcoides spp. which contains all four chloroethene RDase genes. The sum of quantified RDase genes exceeded the Dehalococcoides species 16S rRNA gene copy number in the Evanite culture, indicating that the indigenous Dehalococcoides spp. carry one or a combination of two or more of the analyzed RDase genes.

Abundance and spatial distribution of RDase genes in the flow column.

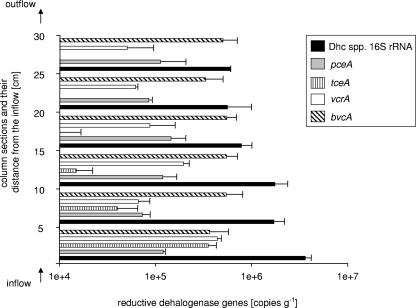

When complete dechlorination of PCE to ethene was observed at the outflow of the column (after 170 days of column operation), the aquifer solids from the continuous-flow column were sampled and analyzed for the spatial distribution and activity of Dehalococcoides species cells and their respective RDase genes. The column was divided into six sections (5 cm each) between the column inflow and outflow ports. We used real-time PCR to monitor the abundance of Dehalococcoides species 16S rRNA and pceA, tceA, bvcA, and vcrA genes in nucleic acid extracts from aquifer solids of each of the six column sections (Fig. 2). Distinct spatial trends of gene distribution were observed: the Dehalococcoides species 16S rRNA gene was detected at (3.6 ± 0.6) × 106 copies/gram in the first 5 cm from the column inflow, decreasing to (1.7 ± 0.5) × 106 copies/gram between 5 and 15 cm from the column inlet and further dropping to between (5.6 ± 0.4) × 105 and (7.9 ± 0.2) × 105 copies/gram in the second half of the column (15 to 30 cm) (Fig. 2). Thus, the Dehalococcoides species population accounted for 1 to 3% of the total Bacteria community in the flow column. The relative Dehalococcoides abundance estimate has to be considered carefully since the determination of total Bacteria 16S rRNA gene numbers by real-time PCR is biased by the various rRNA operon copy numbers in different microbial species (17, 24).

FIG. 2.

Chloroethene RDase gene abundance in the flow column. Gene copy numbers were determined by real-time PCR using template DNA extracted from six different column sections. Each bar represents the average of the results of triplicate real-time PCRs performed on two independent DNA extractions. Dhc, Dehalococcoides.

While all four RDase genes (pceA, tceA, bvcA, and vcrA) were found to be present in the first four sections (0 to 20 cm from the column inflow), the tceA gene could not be detected 20 to 30 cm from the column inlet (Fig. 2). The VC reductase-encoding bvcA gene was the numerically dominant RDase gene in all column sections [(5.6 ± 1.4) × 105 to (3.3 ± 1.7) × 105 copies/gram] except for the section closest to the inflow, in which the RDase genes tceA and vcrA were equally abundant [(3.6 ± 0.8) × 105 and (4.4 ± 0.4) × 105 copies/gram]. The PCE reductase-encoding pceA gene was present in all column sections. pceA gene copy numbers ranged from (1.5 ± 0.6) × 105 to (7.4 ± 1.5) × 105 copies/gram (Fig. 2).

The sum of all RDase genes accounted for 35 to 50% of all Dehalococcoides species 16S rRNA gene copies in the first half of the column (0 to 15 cm). This interesting finding indicates that more than half of the quantified population of Dehalococcoides species cells in the first 15 cm of the column did not contain any one of the four known chloroethene RDases. In the second half of the column (15 to 30 cm), 80 to 120% of the 16S rRNA genes could be accounted for by the sum of all RDase genes (Fig. 2). A recovery rate of more than 100% can be explained by the presence of Dehalococcoides spp., such as strains 195 and VS, which contain a pceA-type RDase gene homolog and, in addition, either a tceA- or vcrA-type RDase gene.

Expression of RDase genes in the flow column.

Total RNA was extracted from aquifer solids sampled from the six 5-cm intervals of the column and served as template in reverse transcription-real-time PCRs to quantify the expression of the four chloroethene RDases. Standard curves generated with plasmid pCR2.1_rdh16S were used to quantify RDase transcript abundance.

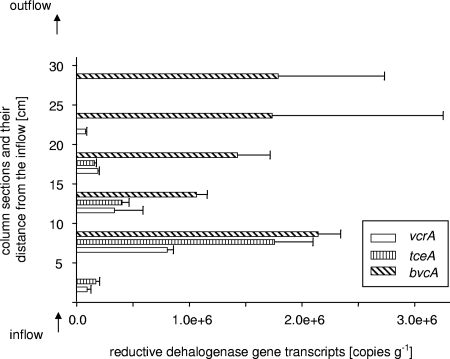

Interestingly, despite the presence of the pceA gene in all six column sections at copy numbers ranging from (7.4 ± 1.5) × 104 to (1.5 ± 0.6) × 105, no transcripts were detected in any part of the column (Fig. 3). Transcripts of the RDase genes tceA, vcrA, and bvcA could be detected throughout most of the column. The highest copy numbers were observed in the section 5 to 10 cm from the column inflow (Fig. 3). While the vcrA and tceA transcript levels gradually decreased with increasing distance from the column inflow, bvcA transcripts never decreased below (1.0 ± 0.1) × 106 copies/gram. bvcA was the only RDase gene expressed in the column section closest to the column outflow (25 to 30 cm) but was not detected in the section 0 to 5 cm from the column inflow (Fig. 3). tceA transcripts were not detected in the sections 20 to 30 cm into the column, and expression of the VC reductase-encoding vcrA could not be detected in the section 25 to 30 cm from the column inflow (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Transcript copy numbers of chloroethene RDase genes in the flow column. Transcript abundance was determined by real-time PCR using template RNA extracted from six different column sections. Each bar represents the average of the results of triplicate real-time PCRs performed on two independent RNA extractions.

Microbial community composition in the column.

A comprehensive description of the phylogenetic affiliation and frequencies of the 16S rRNA gene clone sequences obtained is provided in Table S1 in the supplemental material. In total, 123 bacterial clones were obtained. Sixty-nine clones were retrieved from the 0- to 5-cm section close to the column inflow, and 54 clones were obtained from the section closest to the column outflow (25 to 30 cm). No archaeal 16S rRNA gene sequences were amplified from both sections using two different standard primer combinations (see Materials and Methods). The 16S rRNA gene clones obtained from both libraries showed high sequence similarity (>97%) to environmental clones from other chloro-organic-contaminated environments, but the compositions of the two 16S rRNA gene libraries differed remarkably.

The 0- to 5-cm-section clone library was dominated by two sequence types affiliated with the genus Eubacterium of the phylum Firmicutes. Of 69 clones obtained from this section, 42 clones had 97 to 98% sequence identity with Eubacterium species 16S rRNA sequences. Of the 42 sequences, 23 sequences were most closely related to a sequence of an uncultured bacterium (GenBank accession no. AJ488081) from a chlorobenzene-degrading microbial consortium. The remaining 19 Eubacterium species sequences were most similar to clone sequence ROME195Asa (GenBank accession no. AY998135) from a microbial community inhabiting alternating shale-sandstone units of the continental deep subsurface. Only one of the sequences with high sequence identity to clone sequence ROME195Asa was also found in the clone library from the column outflow section (25 to 30 cm). Sequences found in the 0- to 5-cm-section clone library that were also present in comparable numbers in the clone library from the 25- to 30-cm section belonged to the Propionibacteriaceae (Actinobacteria; 13 clone sequences in the 0- to 5-cm section and 9 clone sequences in the 25- to 30-cm section, with 92 to 99% sequence similarity) and Desulfovibrionaceae (Deltaproteobacteria; 4 and 6 clone sequences in the respective sections, with 92 to 98% sequence similarity). The most-abundant sequences in the clone library from the 25- to 30-cm section were affiliated with the Betaproteobacteria families Comamonadaceae and Oxalobacteraceae of the Burkholderiales (14 out of 54 total clones). The 16S rRNA gene clone sequences unique to the outflow section of the PCE flow column were most similar to uncultured gammaproteobacteria of the Xanthomonadales and the deltaproteobacterium Pelobacter acetylenicus. No Dehalococcoides species sequences were found in both clone libraries. This finding is consistent with the overall low abundance of Dehalococcoides spp. in the column (as determined by real-time PCR) and the small size of our two clone libraries. Interestingly, two sequences from the column outflow section were most closely related to the Anaerolineae, a subphylum of the Chloroflexi with 85% sequence similarity to the Chloroflexi subphylum Dehalococcoides. Finding another Chloroflexi subphylum in the system is interesting because of the possibility of horizontal gene transfer between both related taxa. McMurdie et al. have recently described the alien nature of the vcrA and bvcA codon usage, supporting the theory of a foreign origin of these genes in Dehalococcoides spp. (33).

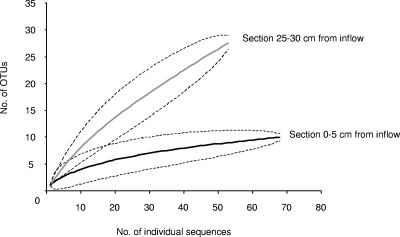

16S rRNA gene sequences of other chloroethene-dechlorinating bacteria, such as Desulfitobacterium spp. or Dehalobacter spp., were not found in the clone libraries and also could not be detected by real-time PCR using the primers designed by Smits et al. (44). Rarefaction curves of both clone libraries are shown in Fig. 4. Sequences were assigned to operational taxonomic units (OTUs) if they were less than 3% different from each other. The rarefaction curves of the two 16S rRNA gene libraries from the different column sections show that each section contained significantly different total numbers of bacterial lineages (P < 0.05). While the richness of OTUs in the clone library from the 0- to 5-cm section (10 OTUs) seems to plateau for the 69 sequences obtained, the clone library from the 25- to 30-cm section did not contain sufficient sequences to provide a robust estimate of species richness. Twenty-eight OTUs for the 54 sequences from this section did not result in a flattening of the respective rarefaction curve (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

Rarefaction curves of two 16S rRNA gene libraries from the PCE-dechlorinating continuous-flow column. The clone libraries were constructed from DNA extracted from column aquifer solids sampled 0 to 5 cm from the column inflow and 25 to 30 cm from the column inflow. Dashed lines represent the >95% confidence interval. Sequences were assigned to OTUs if they were less than 3% different from each other.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we investigated Dehalococcoides species abundance and activity in a modeled aquifer system undergoing reductive dehalogenation of PCE. 16S rRNA gene clone libraries were constructed to gain insights into the microbial community composition at the two opposing ends of the column system. Flow column experiments were conducted with Hanford aquifer material bioaugmented with the Evanite culture, which contained an enriched population of Dehalococcoides spp. (73.5% of total Bacteria 16S rRNA gene copies). The column operation conditions, performance, and chloroethene transformation rates were published previously (3).

Using real-time PCR, we determined the chloroethene RDase gene composition of Dehalococcoides spp. in the Evanite culture. We found that Dehalococcoides species cell numbers in the culture could be fully accounted for by the sum of the quantified chloroethene RDase genes. In contrast, analysis of the flow column aquifer solids after 170 days of column operation revealed that nearly 50% of the Dehalococcoides species population in the first half of the column (0 to 15 cm) contained Dehalococcoides spp. which did not contain any of the four known RDases. This indicates the presence of so-far-uncultured Dehalococcoides spp. which presumably are indigenous to the Hanford aquifer material. Interestingly, no dechlorinating activity was observed in the flow column before bioaugmentation with the Evanite culture (3), which is in agreement with the presence of Dehalococcoides spp. lacking the known chloroethene reductase genes in the Hanford aquifer solids which were used to fill the column. Bioaugmentation of the flow column with the Evanite culture marked the onset of reductive dechlorination, because it introduced Dehalococcoides spp. containing known chloroethene RDase genes into the system.

Futamata et al. took a similar PCR-based approach to investigate the chloroethene RDase gene composition in Dehalococcoides species-containing enrichment cultures on polychlorinated dioxins (9). They report PCE transformation in the absence of any one of the four chloroethene RDase genes (vcrA, bvcA, tceA, and pceA) and concluded that their cultures might include novel Dehalococcoides species-type microorganisms.

We further quantified RDase gene transcripts in total RNA extracted from the different column sections and found that a bvcA-type VC reductase gene was the most transcriptionally active of the four RDase genes analyzed in this study. Except in the first section, bvcA was the most highly expressed RDase gene in all column sections and had the only RDase transcripts detectable closest to the column outflow. The section 5 to 10 cm from the inflow port was the most transcriptionally active column section, with the highest copy numbers for bvcA, vcrA, and tceA. Interestingly, we did not detect any pceA transcripts, although we showed that the pceA gene was present in every column section. Azizian et al. determined the zero-order PCE transformation rates in microcosms inoculated with column material from the different column sections (3). The PCE transformation rates, per gram of aquifer solids, were highest in the first section, 0 to 5 cm from the column inlet (5.5 nmol h−1 g−1) and were decreased by an order of magnitude by the column outlet (0.5 nmol h−1 g−1) (3). The fact that we did not detect any pceA transcripts despite active PCE reduction in the column might indicate that continuous pceA transcription at a detectable level may not be required in Dehalococcoides spp. to maintain PCE dechlorination activity under the prevailing conditions in the column. The known PCE reductase of D. ethenogenes strain 195 (DET0318) has been shown to be bifunctional, also serving as a 2,3-dichlorophenol reductase (8). Only limited information about its predominant in situ function, regulation, and expression exists to date.

The results of pure-culture studies with D. ethenogenes strain 195 revealed that increasing chloroethene respiration rates were not necessarily reflected in an increase of corresponding RDase gene transcript levels (40). The results of microarray and proteomic studies demonstrated that RDase genes other than the designated PCE reductase gene pceA (DET0318) are expressed during reductive dechlorination of PCE by D. ethenogenes strain 195 and that their induction and expression levels vary with electron acceptor concentration (16, 34, 35). However, in these studies, pure and enrichment cultures were used that have been maintained on chlorinated ethenes in laboratories for decades. It is conceivable that Dehalococcoides species RDase genes other than the known pceA function as PCE reductase genes under environmental conditions, including the simulated aquifer conditions in our flow column. In order to identify suitable biomarkers for in situ application it is necessary to study their performance under in situ-relevant conditions (22).

To assess the microbial-community diversity present in the aquifer material from the flow column, we constructed 16S rRNA gene clone libraries from the two opposite ends of the flow column. Based on the number of OTUs found in the two clone libraries, the microbial community near the column inflow, where electron donor and acceptor concentrations were highest, was less diverse than the microbial community at the outflow end of the column. The difference in OTUs found at the opposite ends of the flow column also reflects which electron donors are available at the two column ends (i.e., lactate near the inflow and acetate and propionate near the outflow).

In general, the compositions of OTUs found in the column clone libraries were similar to those detected in a TCE-contaminated aquifer undergoing biostimulation with lactate (26). Both 16S rRNA gene clone libraries were dominated by Clostridia. In contrast to the results of the field study by Macbeth et al., we could not amplify archaeal 16S rRNA gene sequences. The archaeal library of Macbeth et al. consisted of clones affiliated with acetoclastic methanogens (26). Consistent with this observation, we did not find evidence for methane formation during the operation of our flow column (3).

Although not represented in the 16S rRNA gene clone libraries generated with broad-specificity bacterial primers, Dehalococcoides species 16S rRNA genes could be quantified with genus-specific primers in real-time PCR assays. Other known chloroethene-dechlorinating microbial phylotypes, such as Dehalobacter spp. and Desulfitobacterium spp., were not found in the clone libraries either. The presence of both phylotypes could also not be shown with specific primers. We found one phylotype in both clone libraries which was most similar to the genus Sporomusa of the Acidaminococcaceae/Clostridiales. Sporomusa ovata has been shown to dechlorinate PCE to TCE concomitant with homoacetogenesis from methanol and carbon dioxide (46). Sporomusa species phylotypes have also previously been found in chlorinated-ethene-dechlorinating mixed cultures (5, 47).

The column inflow clone library was dominated by 16S rRNA gene sequences affiliated with the genus Eubacterium of the phylum Firmicutes (61% of the total number of clone sequences obtained). Although clone library abundance does not necessarily reflect natural abundance, the dominance of these sequences in the column inflow section is apparent. The Eubacterium species sequences from the column have 97% sequence similarity to Eubacterium limosum. Recently, Yim et al. reported reductive dechlorination of methoxychlor and DDT in pure-culture studies with Eubacterium limosum (48). Based on the clone library results and the lack of pceA expression by Dehalococcoides spp., it is conceivable that Eubacterium spp. could be responsible for the bulk of the PCE dechlorination near the column inflow. Based on 16S rRNA gene phylogeny, the physiological potential of the column microbial community comprised reductive dechlorination, fermentation, homoacetogenesis, and sulfate reduction. Since phylogenetic affiliation does not necessarily reflect metabolic capabilities, inferring the functional capabilities of a microbial community based on 16S rRNA gene phylogeny alone should be done cautiously.

By quantifying known chloroethene RDase genes and their transcripts in a PCE-dechlorinating flow column, we have shown that Dehalococcoides spp. containing functionally different RDase genes occurred spatially separated in the flow column. Spatial separation most likely followed electron acceptor availability. Assuming that Dehalococcoides spp. are the dominant dechlorinating microorganisms in the system, the microbial distribution followed gradients of PCE dechlorination products. Dehalococcoides spp. capable of PCE and TCE dechlorination were present in the lower half of the column near the PCE inflow (0 to 15 cm) where they compete with other potential PCE dechlorinators in the microbial community for electron acceptor availability. Dehalococcoides spp. capable of DCE and VC dechlorination occupied the upper half of the column where most of the PCE and TCE were reduced to DCE and VC (15 to 30 cm). This might explain the higher abundance and activity of bvcA-type VC reductase gene-containing Dehalococcoides spp. in this column half and supports the exclusive role and importance of these Dehalococcoides sp. strains for complete environmental PCE dechlorination. The spatial analysis of Dehalococcoides species chloroethene RDase genes in the PCE flow column provided evidence that complete dechlorination to ethene is a cooperative and nonlinear effort of diverse Dehalococcoides sp. strains that occupy environmental niches according to their functional RDase gene composition.

The results of the present study and of the complementary column study by Azizian et al. (3) demonstrate that RDase genes can serve as a general indicator of the metabolic potential and function of Dehalococcoides spp. by providing useful insights into the organisms' abundance, distribution, and activity. As we continue to study the physiology of Dehalococcoides spp. and characterize new functions of putative RDases and other genes associated with reductive dehalogenation, the applicability of the identified target genes as biomarkers for the in situ monitoring of reductive dechlorination needs to be carefully evaluated. We have shown that continuous-flow columns represent assessable model systems to study the complex interplay of transformation rates, organism distribution, and activity under environmentally relevant conditions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Tina Loesekann for helpful discussions and for critically reading the manuscript. We thank R. Richardson, S. Zinder, and F. E. Loeffler for providing DNA of Dehalococcoides sp. strains 195 and BAV1.

This study was supported through grant R-828772 from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)-sponsored Western Region Hazardous Substance Research Center and funding from the Strategic Environmental Research and Development Program (SERDP) of the Department of Defense, the Department of Energy, and the EPA to A.M.S.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 1 August 2008.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://aem.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adrian, L., U. Szewzyk, J. Wecke, and H. Gorisch. 2000. Bacterial dehalorespiration with chlorinated benzenes. Nature 408:580-583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ashelford, K. E., N. A. Chuzhanova, J. C. Fry, A. J. Jones, and A. J. Weightman. 2006. New screening software shows that most recent large 16S rRNA gene clone libraries contain chimeras. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72:5734-5741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Azizian, M. F., S. Behrens, A. Sabalowsky, M. E. Dolan, A. M. Spormann, and L. Semprini. 2008. Continuous-flow column study of reductive dehalogenation of PCE upon bioaugmentation with the Evanite enrichment culture. J. Contam. Hydrol. 100:11-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.DeLong, E. F. 1992. Archaea in coastal marine environments. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89:5685-5689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Duhamel, M., and E. A. Edwards. 2006. Microbial composition of chlorinated ethene-degrading cultures dominated by Dehalococcoides. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 58:538-549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ellis, D. E., E. J. Lutz, J. M. Odom, R. J. Buchanan, and C. L. Bartlett. 2000. Bioaugmentation for accelerated in situ anaerobic bioremediation. Environ. Sci. Technol. 34:2254-2260. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fennell, D. E., I. Nijenhuis, S. F. Wilson, S. H. Zinder, and M. M. Haggblom. 2004. Dehalococcoides ethenogenes strain 195 reductively dechlorinates diverse chlorinated aromatic pollutants. Environ. Sci. Technol. 38:2075-2081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fung, J. M., R. M. Morris, L. Adrian, and S. H. Zinder. 2007. Expression of reductive dehalogenase genes in Dehalococcoides ethenogenes strain 195 growing on tetrachloroethene, trichloroethene, or 2,3-dichlorophenol. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73:4439-4445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Futamata, H., N. Yoshida, T. Kurogi, S. Kaiya, and A. Hiraishi. 2007. Reductive dechlorination of chloroethenes by Dehalococcoides-containing cultures enriched from a polychlorinated-dioxin-contaminated microcosm. ISME J. 1:471-479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.He, J., Y. Sung, R. Krajmalnik-Brown, K. M. Ritalahti, and F. E. Löffler. 2005. Isolation and characterization of Dehalococcoides sp. strain FL2, a trichloroethene (TCE)- and 1,2-dichloroethene-respiring anaerobe. Environ. Microbiol. 7:1442-1450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.He, J. Z., K. M. Ritalahti, K. L. Yang, S. S. Koenigsberg, and F. E. Löffler. 2003. Detoxification of vinyl chloride to ethene coupled to growth of an anaerobic bacterium. Nature 424:62-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Holmes, V. F., J. He, P. K. H. Lee, and L. Alvarez-Cohen. 2006. Discrimination of multiple Dehalococcoides strains in a trichloroethene enrichment by quantification of their reductive dehalogenase genes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72:5877-5883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hölscher, T., H. Gorisch, and L. Adrian. 2003. Reductive dehalogenation of chlorobenzene congeners in cell extracts of Dehalococcoides sp. strain CBDB1. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:2999-3001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huber, T., G. Faulkner, and P. Hugenholtz. 2004. Bellerophon: a program to detect chimeric sequences in multiple sequence alignments. Bioinformatics 20:2317-2319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jayachandran, G., H. Görisch, and L. Adrian. 2003. Dehalorespiration with hexachlorobenzene and pentachlorobenzene by Dehalococcoides sp. strain CBDB1. Arch. Microbiol. 180:411-416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johnson, D. R., E. L. Brodie, A. E. Hubbard, G. L. Andersen, S. H. Zinder, and L. Alvarez-Cohen. 2008. Temporal transcriptomic microarray analysis of Dehalococcoides ethenogenes strain 195 during the transition into the stationary phase. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74:2864-2872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klappenbach, J. A., P. R. Saxman, J. R. Cole, and T. M. Schmidt. 2001. rrndb: the ribosomal RNA operon copy number database. Nucleic Acids Res. 29:181-184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krajmalnik-Brown, R., T. Hölscher, I. N. Thomson, F. M. Saunders, K. M. Ritalahti, and F. E. Löffler. 2004. Genetic identification of a putative vinyl chloride reductase in Dehalococcoides sp. strain BAV1. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:6347-6351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kube, M., A. Beck, S. H. Zinder, H. Kuhl, R. Reinhardt, and L. Adrian. 2005. Genome sequence of the chlorinated compound-respiring bacterium Dehalococcoides sp. strain CBDB1. Nat. Biotechnol. 23:1269-1273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lane, D., B. Pace, G. Olsen, D. Stahl, M. Sogin, and N. Pace. 1985. Rapid determination of 16S ribosomal RNA sequences for phylogenetic analyses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 82:6955-6959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee, P. K. H., D. R. Johnson, V. F. Holmes, J. He, and L. Alvarez-Cohen. 2006. Reductive dehalogenase gene expression as a biomarker for physiological activity of Dehalococcoides spp. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72:6161-6168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee, P. K. H., T. W. Macbeth, K. S. Sorenson, Jr., R. A. Deeb, and L. Alvarez-Cohen. 2008. Quantifying genes and transcripts to assess the in situ physiology of Dehalococcoides spp. in a trichloroethene-contaminated groundwater site. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74:2728-2739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lendvay, J. M., F. E. Löffler, M. Dollhopf, M. R. Aiello, G. Daniels, B. Z. Fathepure, M. Gebhard, R. Heine, R. Helton, J. Shi, R. Krajmalnik-Brown, C. L. Major, M. J. Barcelona, E. Petrovskis, R. Hickey, J. M. Tiedje, and P. Adriaens. 2003. Bioreactive barriers: a comparison of bioaugmentation and biostimulation for chlorinated solvent remediation. Environ. Sci. Technol. 37:1422-1431. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ludwig, W., and K.-H. Schleifer. 2000. How quantitative is quantitative PCR with respect to cell counts? Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 23:556-562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ludwig, W., O. Strunk, R. Westram, L. Richter, H. Meier, Yadhukumar, A. Buchner, T. Lai, S. Steppi, G. Jobb, W. Forster, I. Brettske, S. Gerber, A. W. Ginhart, O. Gross, S. Grumann, S. Hermann, R. Jost, A. Konig, T. Liss, R. Lussmann, M. May, B. Nonhoff, B. Reichel, R. Strehlow, A. Stamatakis, N. Stuckmann, A. Vilbig, M. Lenke, T. Ludwig, A. Bode, and K.-H. Schleifer. 2004. ARB: a software environment for sequence data. Nucleic Acids Res. 32:1363-1371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Macbeth, T. W., D. E. Cummings, S. Spring, L. M. Petzke, and K. S. Sorenson, Jr. 2004. Molecular characterization of a dechlorinating community resulting from in situ biostimulation in a trichloroethene-contaminated deep, fractured basalt aquifer and comparison to a derivative laboratory culture. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:7329-7341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Magnuson, J. K., M. F. Romine, D. R. Burris, and M. T. Kingsley. 2000. Trichloroethene reductive dehalogenase from Dehalococcoides ethenogenes: sequence of tceA and substrate range characterization. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:5141-5147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Magnuson, J. K., R. V. Stern, J. M. Gossett, S. H. Zinder, and D. R. Burris. 1998. Reductive dechlorination of tetrachloroethene to ethene by two-component enzyme pathway. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:1270-1275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Major, D. W., M. L. McMaster, E. E. Cox, E. A. Edwards, S. M. Dworatzek, E. R. Hendrickson, M. G. Starr, J. A. Payne, and L. W. Buonamici. 2002. Field demonstration of successful bioaugmentation to achieve dechlorination of tetrachloroethene to ethene. Environ. Sci. Technol. 36:5106-5116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Massana, R., A. E. Murray, C. M. Preston, and E. F. Delong. 1997. Vertical distribution and phylogenetic characterization of marine planktonic Archaea in the Santa Barbara channel. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:50-56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maymo-Gatell, X., Y.-T. Chien, J. M. Gossett, and S. H. Zinder. 1997. Isolation of a bacterium that reductively dechlorinates tetrachloroethene to ethene. Science 276:1568-1571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McCarty, P. L. 1997. Microbiology: breathing with chlorinated solvents. Science 276:1521-1522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McMurdie, P. J., S. F. Behrens, S. Holmes, and A. M. Spormann. 2007. Unusual codon bias in vinyl chloride reductase genes of Dehalococcoides species. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73:2744-2747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Morris, R. M., J. M. Fung, B. G. Rahm, S. Zhang, D. L. Freedman, S. H. Zinder, and R. E. Richardson. 2007. Comparative proteomics of Dehalococcoides spp. reveals strain-specific peptides associated with activity. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73:320-326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Morris, R. M., S. Sowell, D. Barofsky, S. Zinder, and R. Richardson. 2006. Transcription and mass-spectroscopic proteomic studies of electron transport oxidoreductases in Dehalococcoides ethenogenes. Environ. Microbiol. 8:1499-1509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Müller, J. A., B. M. Rosner, G. von Abendroth, G. Simon-Meshulam, P. L. McCarty, and A. M. Spormann. 2004. Molecular identification of the catabolic vinyl chloride reductase from Dehalococcoides sp. strain VS and its environmental distribution. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:4880-4888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Muyzer, G., E. C. de Waal, and A. G. Uitterlinden. 1993. Profiling of complex microbial populations by denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis analysis of polymerase chain reaction-amplified genes coding for 16S rRNA. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 59:695-700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Oelmüller, U., N. Krüger, A. Steinbüchel, and G. Cornelius. 1990. Isolation of prokaryotic RNA and detection of specific mRNA with biotinylated probes. J. Microbiol. Methods 11:73-84. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pruesse, E., C. Quast, K. Knittel, B. M. Fuchs, W. Ludwig, J. Peplies, and F. O. Glockner. 2007. SILVA: a comprehensive online resource for quality checked and aligned ribosomal RNA sequence data compatible with ARB. Nucleic Acids Res. 35:7188-7196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rahm, B. G., and R. E. Richardson. 2008. Correlation of respiratory gene expression levels and pseudo-steady-state PCE respiration rates in Dehalococcoides ethenogenes. Environ. Sci. Technol. 42:416-421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ritalahti, K. M., B. K. Amos, Y. Sung, Q. Wu, S. S. Koenigsberg, and F. E. Löffler. 2006. Quantitative PCR targeting 16S rRNA and reductive dehalogenase genes simultaneously monitors multiple Dehalococcoides strains. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72:2765-2774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rozen, S., and H. J. Skaletsky. 2000. Primer3 on the WWW for general users and for biologist programmers, p. 365-386. In S. Krawetz and S. Misener (ed.), Bioinformatics methods and protocols: methods in molecular biology. Humana Press, Totowa, NJ. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 43.Seshadri, R., L. Adrian, D. E. Fouts, J. A. Eisen, A. M. Phillippy, B. A. Methe, N. L. Ward, W. C. Nelson, R. T. Deboy, H. M. Khouri, J. F. Kolonay, R. J. Dodson, S. C. Daugherty, L. M. Brinkac, S. A. Sullivan, R. Madupu, K. E. Nelson, K. H. Kang, M. Impraim, K. Tran, J. M. Robinson, H. A. Forberger, C. M. Fraser, S. H. Zinder, and J. F. Heidelberg. 2005. Genome sequence of the PCE-dechlorinating bacterium Dehalococcoides ethenogenes. Science 307:105-108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Smits, T. H. M., C. Devenoges, K. Szynalski, J. Maillard, and C. Holliger. 2004. Development of a real-time PCR method for the quantification of the three genera Dehalobacter, Dehalococcoides, and Desulfitobacterium in microbial communities. J. Microbiol. Methods 57:369-378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sung, Y., K. M. Ritalahti, R. P. Apkarian, and F. E. Löffler. 2006. Quantitative PCR confirms purity of strain GT, a novel trichloroethene-to-ethene-respiring Dehalococcoides isolate. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72:1980-1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Terzenbach, D. P., and M. Blaut. 1994. Transformation of tetrachloroethylene to trichloroethylene by homoacetogenic bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 123:213-218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yang, Y., M. Pesaro, W. Sigler, and J. Zeyer. 2005. Identification of microorganisms involved in reductive dehalogenation of chlorinated ethenes in an anaerobic microbial community. Water Res. 39:3954-3966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yim, Y.-J., J. Seo, S.-I. Kang, J.-H. Ahn, and H.-G. Hur. 2008. Reductive dechlorination of methoxychlor and DDT by human intestinal bacterium Eubacterium limosum under anaerobic conditions. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 54:406-411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yu, S., M. E. Dolan, and L. Semprini. 2005. Kinetics and inhibition of reductive dechlorination of chlorinated ethylenes by two different mixed cultures. Environ. Sci. Technol. 39:195-205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yu, S., and L. Semprini. 2004. Kinetics and modeling of dechlorination at high PCE and TCE concentrations. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 88:451-464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhao, S., and R. D. Fernald. 2005. Comprehensive algorithm for quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction. J. Comput. Biol. 12:1047-1064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.