Abstract

Context:

Previous researchers have shown that work-family conflict (WFC) affects the level of a person's job satisfaction, life satisfaction, and job burnout and intentions to leave the profession. However, WFC and its consequences have not yet been fully investigated among certified athletic trainers.

Objective:

To investigate the relationship between WFC and various outcome variables among certified athletic trainers working in National Collegiate Athletic Association Division I-A settings.

Design:

A mixed-methods design using a 53-item survey questionnaire and follow-up in-depth interviews was used to examine the prevalence of WFC.

Setting:

Division I-A universities sponsoring football.

Patients or Other Participants:

A total of 587 athletic trainers (324 men, 263 women) responded to the questionnaire, and 12 (6 men, 6 women) participated in the qualitative portion of the mixed-methods study.

Data Collection and Analysis:

We calculated Pearson correlations to determine the relationship between WFC and job satisfaction, life satisfaction, and job burnout. Regression analyses were run to determine whether WFC was a predictor of job satisfaction, job burnout, or intention to leave the profession. Interviews were transcribed verbatim and then analyzed using the computer program N6 as well as member checks and peer debriefing.

Results:

Negative relationships were found between WFC and job satisfaction (r = −.52, P < .001). Positive were noted between WFC and job burnout (r = .63, P < .001) and intention to leave the profession (r = .46, P < .001). Regression analyses revealed that WFC directly contributed to job satisfaction (P < .001), job burnout (P < .001), and intention to leave the profession (P < .001).

Conclusions:

Overall, our findings concur with those of previous researchers on WFC and its negative relationships to job satisfaction and life satisfaction and positive relationship to job burnout and intention to leave an organization. Sources of WFC, such as time, inflexible work schedules, and inadequate staffing, were also related to job burnout and job dissatisfaction in this population.

Keywords: burnout, attrition

Key Points.

In these Division I-A athletic trainers, work-family conflict was inversely related to job satisfaction. Positive correlations were noted between work-family conflict and job burnout and work-family conflict and intention to leave the profession.

Our findings are similar to those of other researchers studying work-family conflict in a variety of populations.

Future investigators should focus on identifying successful strategies for mitigating the occurrence of work-family conflict and its negative consequences.

Recently, we have seen an influx of empirical and anecdotal literature regarding the topic of quality of life for certified athletic trainers (ATs).1–9 Overwhelmingly, the long work hours necessary to meet the AT's job-related responsibilities permeate the discussions regarding the overall quality of life for an AT.1,2,4,5,7–9 Work time has consistently been cited as the foundation for the occurrence of work-family conflict (WFC),10–16 a construct that may influence the quality of life for an individual. The WFC occurs when individuals experience difficulties managing responsibilities in their personal lives due to professional work demands.17 Other sources of WFC include work overload,18 time spent away from home,10–16 and lack of work schedule flexibility.19,20 Scholars, in addition to examining the antecedents of WFC, have begun to investigate its effect on such constructs as job satisfaction, life satisfaction, job burnout, and intentions to leave a profession. As indicated by separate meta-analyses conducted by Kossek and Ozeki21 and Allen et al,22 WFC is consistently associated with job dissatisfaction,6,14,17,21–24 burnout,6,14,17,21–23 turnover or intentions to leave the organization, 6,14,17,21–24 and marital and life dissatisfaction.6,17,21,22,24,25

Although WFC has been exhaustively studied, the construct has only recently gained more attention for those professionals working in the sport industry, particularly coaches15,16,26 and ATs.2–6 Building upon the work of Milazzo et al,6, in which the researchers used quantitative methods to examine the effect of WFC on a variety of outcome variables among a small number of National Collegiate Athletic Association Division I ATs, we used a mixed-methods approach to investigate the occurrence of WFC, sources of WFC, and the effect of WFC upon several outcome variables. In order to accurately depict and discuss the concept of WFC among Division I-A ATs, we chose to present the findings in 2 papers. In the first,4 we discussed the sources of WFC for Division I-A ATs, which included the time commitment needed to meet job-related responsibilities, inflexible work schedules, and work overload. Furthermore, as indicated by previous researchers, we discovered that regardless of marital or family status, WFC was occurring within the profession of athletic training, particularly at the Division I level.

In this second paper, we intend to discuss the effect of WFC on several variables, including job satisfaction, life satisfaction, job burnout, and intention to leave the profession. Moreover, we were interested in comparing the effect of WFC upon those previously listed variables to other working professionals21,22 as well as the findings of Milazzo et al.6 The following research questions guided our manuscript development: (1) Does WFC negatively affect job and life satisfaction among Division I-A ATs? and (2) Does WFC lead to job burnout and thoughts of leaving the profession for Division I-A ATs?

Methods

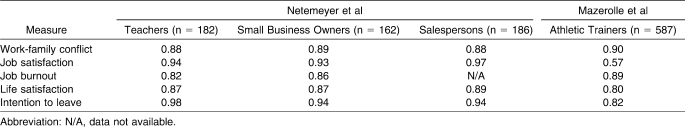

The methods used in this manuscript are substantially the same as those previously described in Part I. However, in part I,4 only those items pertaining to WFC and sources of WFC were discussed. For this manuscript, we include the remaining items on the 53-item questionnaire as well as those questions on the interview guide. Table 1 provides a comparison of a coefficients from Netemeyer et al17 and our study. Following is a discussion of those constructs not discussed in the previous manuscript. See Appendix for the interview guide.

Table 1.

Comparison of α Coefficients From Netemeyer et al17 and the Current Study

Work-Family Conflict

Work-family conflict was measured on a 5-item scale, which was scored by a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Sample items included “The demands of my work interfere with my home and family life,” “I often have to miss important family activities because of my job,” and “There is conflict between my job and the commitment and responsibilities I have to my family.”

Job Satisfaction

Job satisfaction (JS) was measured by 8 items, which were modified from Netemeyer el al.17 Modifications and additions made to the 8-item scale used by Netemeyer el al17 reflected those job satisfaction items found to be important to athletic trainers in studies conducted by Barrett et al27 and Capel.28 The 8-item scale was scored by a 7 point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Sample items included “I am satisfied with my pay,” “I work a reasonable number of hours,” “I have flexibility in my work schedule,” and “Overall, I am satisfied with my job.”

Life Satisfaction

Life satisfaction (LS) was measured by a 5-item scale, which was adapted by Netemeyer et al17 from a scale measuring general happiness with life. The scale was scored on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Sample items included “In most ways my life is close to my ideal,” “The conditions of my life are excellent,” and “So far I have gotten the important things I want in life.”

Burnout

Items utilized to assess job burnout (JB), which were initially adapted by Netemeyer et al17 from the Maslach Burnout Inventory (BMI), were assessed by a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (never) to 7 (always). Sample items from the 6-question section included “I feel emotionally drained from my work,” “At the end of the day I feel used up,” “I feel burned out from my work,” and “I am working too hard on my job.”

Intention to Leave

Intention to leave (ITL)17 or search for another position was measured by 5 questions on a 7-point Likert scale that ranged from 1 (never) to 7 (frequently) and examined a D-IA ATC's propensity to leave the job. Questions were modified from the 7-item scale of Netemeyer et al17 to reflect the sample population. Sample items from this section included “I have searched for an alternative job setting within the profession of athletic training,” “I am actively searching for a job within the profession of athletic training,” “I have searched for a job outside the profession of athletic training,” and “I am actively searching for a job outside the profession of athletic training.”

Interview Guide

The interview guide was constructed to further evaluate the topic of WFC and was developed using current WFC literature and results generated by the survey. The interview guide, which was developed by us and then reviewed by our peer debriefer (an individual with knowledge of the topic and profession of athletic training) for clarity and content, included a background questionnaire similar to the survey (eg, hours worked, marital and family status) and asked participants if they experienced WFC and, if so, how they managed those conflicts. See Appendix 1 for the Interview Guide.

Procedures

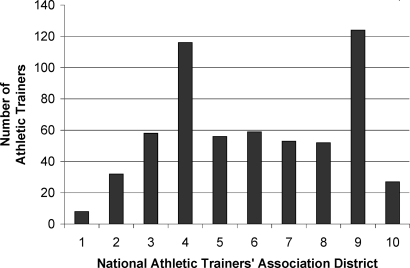

The survey instrument developed and validated by Netemyer et al17 was given to a panel of experts (n = 6) to review before survey distribution. The panel of experts included ATs and professors of athletic training who reviewed the document for specific content related to athletic training. Additionally, sport management researchers with previous mixed-methods, qualitative research experience and knowledge of the profession of athletic training reviewed the document for clarity, content, and methodologic procedures. After receiving approval from the institutional review board, we sent packets directly to the head ATs at 116 of the 117 (1 school participated in a pilot study) universities sponsoring football. See Figure 1 for survey respondents across National Athletic Trainers' Association (NATA) districts. Included within the packet was (1) a cover letter to the head AT explaining the study and directions for distribution to the staff, (2) consent letter for each of the potential respondents assuring confidentiality and anonymity, (3) the survey instrument, and (4) a self-addressed, stamped envelope for direct mailing back to the researchers. Questionnaires were coded to identify the university only, and confidentiality of each participant was assured in individual letters to the participants. Approximately 3 weeks after the mailing, in an attempt to increase the response rate, an e-mail message was sent to all head ATs reminding them to distribute the surveys.

Upon completion of data collection and analysis, one-on-one follow-up interviews were conducted with ATs in various positions within the collegiate setting. We used a convenience sample to identify potential participants and then a snowball sample to recruit the remaining participants. In the end, 12 ATs representing the 3 Division I-A schools with football and the position and sex breakdown previously mentioned participated in the in-person interviews.

Figure. Survey respondents by National Athletic Trainers' Association district.

During each of the 12 individual interview sessions, demographic information was gathered subsequent to gaining the participant's consent. The semistructured interview sessions were organized as follows: (1) daily routine, (2) JS, (3) WFC, (4) family satisfaction, (5) LS, (6) JB, and (7) ITL. In order to limit the potential for researcher bias to affect the qualitative portion of the study, member checks, peer debriefing, and triangulation of data collection methods were used. The interviews were documented through field notes and tape recorded. After completion of each interview, a member of the research team transcribed the interview, using pseudonyms to identify participants. Completed transcripts were electronically sent to each of the participants as a form of member checking. Interview transcripts, coding sheets, and theme interpretations were then shared with the peer debriefer, an AT with previous research experience in WFC. Triangulation of methods was accomplished via a background questionnaire, field notes, and the individual interviews as well as interviewing individuals holding different positions (ie, head AT, assistant AT, graduate assistant AT, program director) within athletic training.

Data Analysis

We analyzed the quantitative data using SPSS (version 10.5; SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL). Demographic data, WFC, and outcome variable scores were calculated using percentages, means, and frequencies. Pearson correlations were conducted to evaluate the relationships between WFC and JS, LS, JB, and ITL. Regression analyses were calculated to determine whether WFC was a predictor of JS, JB, and ITL for this group of ATs.

The themes from the interviews were initially categorized based upon the research questions developed before we conducted the research. Then, after transcription was completed, we independently hand coded the data with multiple colored pens to match the emerging themes. Next, the data and emerging theme structure were loaded into the software program N6 (QSR Intl, Cambridge, MA) to aid in connecting emerging ideas and themes in the data.

Results

Descriptive Analyses

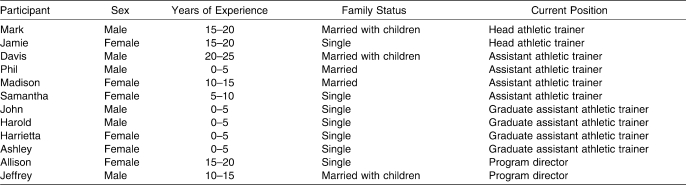

Our response rate was calculated by utilizing data generated by NATA membership statistics,29 which revealed 2132 certified members employed at the Division I level. Of those 2132 members, according to ATs' self-reports of their current positions, an estimated 66% were practicing clinically.29 Therefore, the overall n was 1407. Of those 1407, 587 responded and provided usable data for analysis, yielding a response rate of 42%. Of this sample, 55.2% (n = 324) were male and 44.8% (n = 263) were female. Most of the respondents were assistant ATs (46.9%, n = 275); 34.8% (n = 204) were graduate assistant ATs, and 18.3% (n = 108) were head or associate ATs (head AT, 12.6%, n = 74; associate AT, 5.7%, n = 34). In addition to their athletic training duties, 27.4% (n = 159) were Approved Clinical Instructors, and 26% (n = 151) were responsible for classroom instruction within athletic training education programs. Of the female respondents, 76.8% (n = 202) were single, 16.7% (n = 44) were married, 5.7% (n = 15) were living with their significant other, and 0.8% (n = 3) were divorced. Of the male respondents, 36.4% (n = 118) were single, 53.7% (n = 174) were married, 7.4% (n = 22) were living with their significant other, 2.2% (n = 7) were divorced, and 0.3% (n = 1) were separated. A total of 24.2% (n = 142) of respondents had children. Of those respondents, only 7.6% (n = 20) of the females had children, compared with 37.7% (n = 122) of the males. Table 2 presents the background information regarding the interview participants.

Table 2.

Participants' Demographic Information

Work-Family Conflict and Job Satisfaction

Quantitative Results

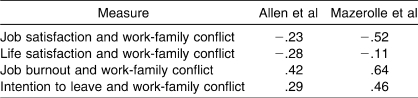

Pearson correlations revealed that ATs at the Division I-A level who experienced higher perceived levels of WFC tended to have lower levels of job satisfaction (r = −.52, P < .001). Table 3 provides a comparison between our results and a meta-analysis conducted by Allen et al.22 Work-family conflict provided a statistically significant explanation of the variance in JS: R2 = .162, R2adj = .160, F1,579 = 111.69, P < .001.

Table 3.

Comparison of Correlations Between Allen et al22 and the Current Study

Qualitative Results

Three major themes were identified as sources of job dissatisfaction for this group of Division I-A ATs: work time, flexibility of work schedules, and staffing patterns. Six ATs said that time constraints related to their positions were the least satisfying factors. While discussing his job-related responsibilities, John bluntly stated, “[I would most like to change] the hours [associated with completing job-related responsibilities].” Additionally, Mark, when asked what he did not like about his job, stated, “If I could just shorten the [work] day.” Davis did not hesitate when describing what he would change about his job: “I would definitely change the travel and the time constraints [of my position].”

Four ATs mentioned that the irregularities or lack of flexibility contributed to their dissatisfaction with their positions. Madison mentioned the importance of the coaching staff with regard to the flexibility and control over work schedules: “ultimately, the head coach has the control over the schedule and the hope is the coach involves you.” Harold echoed Madison's concerns by stating, “yes, [I would like to have a] more flexible schedule.” Ashley, when asked what she would change about her current position, similarly stated, “Not knowing ahead of time your [work schedule].”

Eleven ATs discussed the lack of staffing, which increased work time, as a problematic element to their positions. Overall, many discussed staffing patterns throughout the interviews and felt the staffing patterns were a catalyst to WFC and increasing levels of job dissatisfaction. Jamie discussed needing and wanting more full-time staff members at her institution in order to help manage the demands. When asked what she would like to change about her current work situation, she reflected by saying, “I do not think I would personally want to change anything about my position, but as far as the job in general, we would like to add more positions.”

John, when asked what can be done to improve the overall quality of an athletic training position, stated, “It is not so much the profession thing, but a staffing issue at each of the universities. The more staff the fewer hours [we have to work].”

The 3 sources of job dissatisfaction discussed by the interview participants help explain the relationship we found with the Pearson correlations and regression analysis. Time, flexibility, and staffing patterns were all cited by this group of participants as sources of WFC in addition to sources of job dissatisfaction.

Work-Family Conflict and Life Satisfaction

Quantitative Results

Life satisfaction was negatively influenced by WFC among this group of ATs. However, the relationship was not significant (r = −.11, P = .070). Table 3 provides a comparison between our results and a meta-analysis conducted by Allen et al.22

Qualitative Results

All the interview participants discussed maintaining balance between work and personal life as a way to assess their LS. John stated, “Being happy at work and being able to balance that with some type of a social life.” Consistently, the participants discussed wanting more personal time or time with family when discussing what they would change about their current life situation. Mark affirmed, “More time with my family.” Phil echoed the same thoughts when asked about his personal life, “Spend time with my family [spouse and parents].”

Comparable with the demographic make-up of the survey respondents, many of the interview participants were single and did not have families of their own (7 of 12). See Table 2 for the demographic characteristics of the interview participants. Many of the younger interview participants discussed wanting to have more time to see their families but did not feel as though they were as greatly affected by their current positions as if they would be if they were married with children. Samantha stated,

I do not think not having as much time to spend with my parents [due to my work schedule] really impacts with level of satisfaction as much as it would if I had a significant other. If I did, then not seeing them would be a different story.

The 3 previous quotes support the idea that a decrease in time available to be involved with personal or home life activities (experiences of WFC) can negatively affect an AT's level of LS.

Work-Family Conflict and Job Burnout

Quantitative Results

Pearson correlations revealed that those ATs who had higher WFC scores also had higher scores for JB (r = .63, P < .001). See Table 3 for a comparison between our results and a meta-analysis conducted by Allen et al.22 Work-family conflict provided a statistically significant explanation of the variance in JB(R2 = .389, R2adj = .386, F1,256 = 162.805, P < .001.

Qualitative Results

The interview participants discussed during the interview session at some point during their careers having feelings of JB or concerns for the potential for burnout. Mark described his feelings of JB as his in season continued on:

Yes, I have felt burned out. For example: In the month of September, we played 5 games in 4 weeks. Prior to that, we had just come off of training camp and were going every single day since the first of August. Now you are pressing into October, and you do not know what day of the week it is. That is when I know I am absolutely exhausted.

Samantha reflected,

I don't think I have been burned out. I am tired, and I am bored, but I do not think I have come close to being burned out, well…maybe that is a part of it, so I guess I could be headed that way.

All 12 interview participants acknowledged a time when they were burned out from their jobs or voiced concern for the future regarding burnout. In the end, sources of burnout permeated from the nature of the profession (long hours, inflexibility, and role overload/staffing). Harold, when asked to discuss a time when he felt burned out, voiced his frustration with many facets of the profession:

Combination of the hours, lack of personal life, coaches always riding you, when there is an injury a coach thinks you have magical powers and can control it, but realistically you do not at all. Basically, your life is affected by everyone, and most time coaches and athletes do not realize it.

Two other ATs shared almost identical statements regarding whether job burnout was a concern for the future: “Yes [in the future], mainly because of the hours, the demands, and the inflexibility of the work schedule” and “Yes, I can see myself becoming burned out if the low pay continues with the number of hours.”

Experiences of burnout were mediated by the organizational characteristics of the athletic training profession, which were also found to be catalysts of experiences of job dissatisfaction and WFC among Division I ATs.

Work-Family Conflict and Intention to Leave

Quantitative Results

Pearson correlations revealed that ATs who experienced higher perceived levels of WFC had higher levels of intention to leave an organization (r = .46, P < .001). For a comparison of our results and a meta-analysis conducted by Allen et al,22 see Table 3. Work-family conflict also provided a statistically significant explanation for the variance in intention to leave the profession (R2 = .120, R2adj = .118, F1,556 = 75.735, P < .001).

Qualitative Results

Organizational factors related to the profession and family were the 2 major themes that emerged as contributing factors to feelings of leaving the profession among this group of ATs. Similar to those findings of JS and JB, interview participants discussed how the long hours, coupled with low pay or lack of overtime pay, created the potential for attrition. Jamie had this to say about attrition in the profession:

I think the hours are definitely an issue with a lot of people, because as a society people are used to getting compensated for what they work. Unfortunately, no one is in a position to pay an athletic trainer an hourly wage and expect them to work the hours we put in, especially at the college setting. I think that is most often the reason people will leave the profession.

Phil bluntly stated, “[My reason for searching is] the hours, the pay, and the travel.”

Another AT directly related attrition and the young demographic make-up of the profession to staffing issues by saying

I also think that until staffing issues are addressed and our profession and administrators are educated on the need for adequate staffing, we will always be seen as a young profession.

Lack of personal and family time were also discussed as potential reasons for ATs to seek employment outside the Division I level or the profession. Harrietta discussed a colleague's struggle:

I know a lot of people who are looking to or have left because they want to have a family…A good friend of mine is getting ready to have a baby, and she may never return to the profession after having the baby.

Jamie, the head AT at her institution, was upset that a talented female AT choose to leave her position due to her struggle balancing her career and family life.

We had an assistant athletic trainer who was married when she took the job and was here three years and did a great job for us. Then she decided to start a family but struggled with it. She loved her job but ended up leaving because regardless what we did, there was still some travel involved and there was no way around it. For me it was discouraging because she wanted to stay and she was a good employee, but also she had an obligation to her daughter and her husband. And I wish there was something we could do about that.

Phil believed that the combination of the hours and the lack of family time led to ATs leaving the profession.

These two things go together (hours and salary). It is a lot of hours with low pay. It is those factors, but it really is one in the same. If you worked long hours with a lot of pay or less hours with low pay, it would be better. It is hard for people to imagine successfully having a career and a home and a family life while working all those hours and having such low pay.

Work time, which also created a lack of time at home, was identified as a catalyst for intention to leave the profession of athletic training, which supported the findings of the Pearson correlation and regression analysis.

Discussion

Our primary focus was to investigate whether experiences of WFC affected a Division I-A AT's level of JS and LS as well as if these experiences led to an increase in JB and ITL. Overall, this mixed-methods study revealed that, for an approximately 600-member sample group of Division I-A ATs, the experiences of WFC led to lower levels of JS and LS and stimulated feelings of JB and ITL. Furthermore, sources of job dissatisfaction, JB, and ITL were comparable with those of WFC for this group of ATs.2,4

Work-Family Conflict And Job Satisfaction

Our findings support those of previous researchers regarding JS and WFC6,14,17,21–24 and demonstrate that increased levels of WFC were negatively related to JS for this population. Furthermore, when compared with the meta-analysis conducted by Allen et al,22 the results revealed a stronger negative relationship between JS and WFC. These findings suggest that the conflicts experienced by ATs at the Division I-A level have a stronger effect on an individual's overall assessment of his or her job than those of other working professionals. Additionally, the relationship between JS and WFC was consistent with the findings of a preliminary quantitative study6 of WFC among Division I ATs.

Workplace characteristics such as work hours, work scheduling, travel, and job stress have been documented as organizational factors influencing the occurrence of WFC15,16,19,20 as well as JS.20 For this sample population of ATs, organizational factors such as the amount of time spent working, flexibility of work schedules, and staffing patterns were identified as sources of job dissatisfaction, which interestingly have been documented as antecedents of WFC among collegiate coaches15,16 as well as Division I ATs.2,4 Although a considerable amount of research has been conducted examining the relationship between WFC and JS,6,14,17,21–24 no authors have examined the mediating factors of that relationship. Boles et al19 suggested that flexibility in the workplace, which allows professionals to meet certain home responsibilities, can reduce the occurrence of WFC. Additionally, flexible work schedules, working from home, or negotiable assignments are examples of organizational support, which are linked to increased levels of JS,20 as are policies that can assist professionals in balancing their work and family needs.15,16,26 Unfortunately, for Division I-A ATs, many of the organizational support policies previously mentioned to help manage work and family are not yet available, which in turn seemed to influence ATs' perceptions of their level of JS. It is plausible that long work hours can be compounded by a limited number of full-time staff members to cover all sport assignments, which in turn increases the workload and reduces the flexibility available for an AT. Additionally, it has been suggested that regardless of family status, WFC affects all professionals at some point during their careers30; therefore, it is important to consider policies to create flexibility in work schedules for all ATs. In the future, researchers should investigate which organizational policies can be implemented for all ATs to mitigate the occurrence of WFC, which may in turn reduce job dissatisfaction.

Although regression and correlation analyses revealed a relationship between WFC and JS and the 3 major sources of job dissatisfaction were parallel to antecedents of WFC for the same population, a connection between the 2 constructs was not made by the interview participants. One reasonable justification for this occurrence centers on the interview questionnaire. The questions did not ask participants which factors caused them to experience WFC, only if they were currently experiencing the conflict and if work interfered with their personal time more often than personal time interfered with work. In the future, participants should be asked directly which factors lead to their experiences of WFC.

Work-Family Conflict and Life Satisfaction

Although the results generated in the current study correspond with the negative relationships between LS and WFC found by previous researchers,6,17,21,22,24,25 the strength of the relationship between the variables was weak. The best explanation for the weak relationship may be that a majority of the participants were young, single, and without children. Although their personal time is not seen as less valuable and it is documented that all individuals to a certain degree experience WFC,30 parental responsibilities may increase the experience of WFC for working professionals.31 It is important to note that the demographic make-up of the survey respondents was similar to that of the interview participants. Several interview participants, who did not feel as though they were experiencing much WFC, attributed it to their marital and family status, thus supporting previous findings.

The theories of separation and integration represent another plausible explanation that warrants more investigation.32 Individuals may choose to keep their work and home lives separate, which in turn limits the negative and positive influences one might have over the other. An individual with this mindset, although working long hours and having limited time for personal obligations, may not negatively relate the domains, therefore explaining the correlation analysis. On the contrary, integration may also reduce the perceptions of WFC. Those individuals who consider work and family to be integrated often prioritize both work and family, meaning that individuals should be able to find satisfaction in both work and personal lives, regardless of the actual amount of time spent in each domain.32 So, for ATs, regardless of the hours worked, as long as they have the ability to spend time in both domains during the day, they feel satisfied with their lives. Thus, this frame of mind (integration) may be one more explanation for the lack of significance in the relationship between WFC and family satisfaction for this population of working professionals. Additional research is necessary to determine whether this is a plausible explanation for the relationship between WFC and LS.

As ATs spend more time away from home due to travel and long work hours, they have less time to spend meeting personal obligations, which can reduce their overall LS. Needless to say, although having a balance was important to the interview participants, WFC did not appear to strongly influence LS for the ATs in this study. Perhaps this is because a majority of Division I-A ATs who participated in our study were young, single, and able to balance the responsibilities associated with both work and life or they have adopted the practice of separation or integration.

Work-Family Conflict and Job Burnout

For this group of ATs, as feelings of WFC increased, so did the level of burnout, which is again supported by previous research.6,14,17,21–23 In addition, the relationship between the two was stronger for JB when compared with those weighted correlations calculated by Allen et al22 and analogous when compared with previous research examining WFC and job constructs among ATs.6 This correlation suggests that for Division I-A ATs, the struggle to find a balance between work and family can significantly affect their level of JB. Furthermore, it appears as though the effect was greater for the Division I-A AT than for other working professionals.

Similar to the findings of Pitney8 and other researchers examining burnout among collegiate ATs,33,34 the number of hours worked was a major contributing factor to burnout for this group of ATs. Coaching, a profession with parallel job responsibilities to athletic training, traveling35 and long work hours,35 has been linked to JB, which in turn has been linked to WFC.6,14,17,21–23 In addition to time away from home and long work hours, inflexibility of work schedules, and work overload (due to lack of staffing) were identified as the foundation to JB for this group of ATs; all these organizational factors related to athletic training were previously identified as antecedents to WFC,2,4 as well as job dissatisfaction. Kalliath and Morris36 found that job dissatisfaction was a strong predictor of burnout in nursing professionals. It is conceivable, then, that the constant struggle to find time to meet personal obligations due to work-related responsibilities negatively affects ATs' perceptions regarding their current positions, and as they continue to work in those stressful environments, they experience burnout.34

Although WFC explained a significant portion of the variance in JB for ATs, other variables may play a role. One plausible explanation for the occurrence of JB in this group, which warrants further investigation, is role conflict. Henning and Weidner37 found that ATs were experiencing role strain, particularly those ATs who served as Approved Clinical Instructors. Within this population, 27.4% of respondents served as Approved Clinical Instructors, 26% had teaching duties in addition to their clinical responsibilities, and 34.8% were graduate assistant athletic trainers, a population often evaluated for role conflict. Individuals, particularly ATs, who work in stressful situations or who are unhappy with their positions or have a lack of understanding of their roles or are overloaded in their roles may be more susceptible to JB. Additionally, role-related stress could be an influential cause of burnout among this group. In addition to their work-related roles, ATs assume roles outside the workplace, and as they attempt to balance both their personal and professional roles, they may experience role conflict. It is documented that athletic training can be a stressful profession and can lead to burnout,33,34 and as ATs continue to prioritize work, they are unable to be as involved with their other roles, which could lead to WFC. Future researchers need to investigate the relationship among role strain, burnout, and WFC.

Work-Family Conflict and Intention to Leave

Again, comparable with the findings of Milazzo et al6 and previous researchers, WFC6,17,21,22,24,25 was positively related to ITL for this group of ATs. Moreover, when compared with the results gathered by Allen et al22 and Milazzo et al,6 the relationship was much stronger between the variables. Although the regression findings explained a statistically significant portion of the variance in propensity to leave, other factors not addressed by the survey but noted by the interview participants contributed to an AT's ITL. The first was linked to the lack of flexible work schedules and the time spent away from home. Flexible work schedules have often been cited as an organization's attempt to accommodate the family needs of their employees.19 When family responsibilities are being met through flexible work schedules, conflicts between work and home occur less frequently, which in turn may reduce the prevalence of ITL among ATs. The second factor, locus on control, has been linked to burnout among ATs33 and cited as a prime reason for ATs to leave the profession entirely.28 Many participants felt lack of control over their work schedules was problematic, especially in managing their personal responsibilities. Finally, family-related issues, specifically time spent away from the family, were discussed by many participants. For an AT to leave the profession entirely, long work hours and locus of control were contributing factors.28 Female ATs considered these factors primary concerns for their futures in the profession. Similarly, the results of a Women in Athletic Training Committee survey conducted in 1997 revealed family/personal time as a major concern for female ATs.38 Further, the results are similar to the findings of Pastore39 among collegiate coaches, which linked decreased time with family as a reason to leave the coaching profession and demonstrated that coaches and administrators were more likely to remain in their positions when work and family balance was maintained.40 Again, as previously discussed, sources of JB and job dissatisfaction (nature of the profession) are equivalent to those sources of ITL, which have been cited as antecedents to WFC for this population.

It is important to note that ITL is only a predictor of attrition and does not account for actual attrition. In the future, it is important to investigate whether WFC directly influences ATs to leave the profession entirely. Additionally, organization commitment, a construct directly linked to WFC, has been found to decrease when WFC increases.17,22 Although it was not a focal point of our research or reported within our results, several participants in the interview group mentioned administrative support, which Pitney8 also noted as affecting quality of life. Those ATs who do not feel as though they are supported, particularly if they are overworked and experiencing WFC, may be less committed to their position or profession, thus creating thoughts of leaving or actual attrition. Future researchers should investigate whether the role of the administrator (supervisor, athletic director, head AT) mitigates the experiences of WFC as well as ITL. Additionally, the development of organizational policies that help to mitigate WFC, such as on-site day care and flexible work schedules, should be investigated in order to increase the level of organizational support and reduce WFC.

Limitations

We recognize that not all the findings from our study are transferable to other clinical settings within our profession. Additionally, the thoughts and ideas expressed by the interview participants represent their own personal experiences and opinions and are not meant to be generalized to all ATs, but these personal experiences form a foundation for understanding the concept of WFC and its consequences among athletic training professionals. Finally, all the constructs of the WFC survey except for JS had strong internal consistency. Although the Netemeyer et al17 scale demonstrated strong internal consistency for the JS factor, we opted to modify the scale in order to more accurately reflect the job-related responsibilities of athletic training. The modifications to the JS items did result in a lower reliability coefficient (.57); however, this did not significantly influence the study findings, as the data for WFC and JS in this study were similar to those from other researchers examining WFC and JS. Regardless, in the future, a more reliable scale for JS should be used to compare the relationship between WFC and JS.

Conclusions

Work-family conflict is a demonstrated concern for ATs2–6 and strongly influences JS, JB, and ITL for Division I-A ATs. Except for LS, values for all other variables examined within this study were much higher than those noted in the meta-analyses conducted by Kossek and Ozeki21 and Allen et al,22 suggesting that the influence of WFC is much stronger for ATs than for other working professionals. Future researchers need to continue to explore this construct and strategies to mitigate its occurrence and negative consequences. By doing so, the profession may be able to reduce the occurrence of WFC and help retain young, talented ATs, regardless of their marital and family status. Moreover, it may be advantageous for AT educators to discuss the topic of work and family balance with senior level athletic training students in order to help reduce its occurrence as they enter the workforce.41

Several directions exist for future investigations. A large portion of the empirical data on WFC,2–6 JS,27 and JB33,34 has focused primarily on the Division I clinical setting. Similar sources of WFC have been found to cause lower levels of JS, increased feelings of JB, and stimulated ITL for ATs at the Division I level; however, this may not be the case for those employed in various other clinical settings. Additionally, further inquiry into these clinical settings may uncover successful strategies employed to mitigate the occurrence of WFC and its negative consequences. Secondly, future authors should continue to look at WFC, JS, and JB satisfaction in ATs to provide more data that might assist in improving work conditions and lessening attrition resulting from any of those constructs. Thirdly, WFC has been linked to a wide variety of consequences; therefore, it is important for future researchers to examine other constructs, such as the psychological and physical consequences related to WFC. We were only concerned with those variables related to job (JS and JB) and off-job (family and LS) constructs. Moreover, investigators should examine causes other than family-related issues regarding thoughts of leaving and attrition, such as ATs' salaries and how low salaries can influence the experience of WFC. Finally, future researchers should examine how ITL (which can lead to attrition) are being handled by the profession and by universities.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the certified athletic trainers who took the time to participate in this research study, as well as the Graduate School at the University of Connecticut for funding this project.

Appendix. Interview Questionnaire

Tell me a little about yourself, your daily routine. Does your routine change or differ from season (in versus out)?

Job Satisfaction

What aspects of your job do you enjoy most?

What aspects of your job do you least enjoy?

If you could, what would you change about your current position?

Family Satisfaction

Tell me more about your family. What aspects of family are most important to you?

What impacts your level of family satisfaction?

What would you change about your family and your role in your family if you could? Not going after any deep-seeded family secrets here but more about how they balance and the time they give to family.

Work-Family Conflict/Family-Work Conflict

Do you feel that you experience conflicts between your home and family life?

If so, how do you manage those conflicts? Does anyone help you manage those conflicts?

-

Do you feel more conflicts between your home to work versus work to home?

Why?

Does that impact your feelings/conflicts at home/work?

Life Satisfaction

Would you say that you are satisfied with your life overall?

What impacts your level of satisfaction?

What would you change about your life if you could and why?

Burnout

Give me an example of when you have questioned your desire to remain in athletic training or explain a low point you have experienced in your job. Do you consider yourself to be burned out?

If so, why? If not, why?

How do you cope with low points at work?

Propensity to Leave the Profession

Have you looked for an alternate position within the field? What are your reasons?

Have you looked for a position outside the profession? Why?

Do you see those reasons changing in the future?

What can the profession do to prevent others from leaving in the future?

Footnotes

Stephanie M. Mazerolle, PhD, LAT, ATC, and Jennifer E. Bruening, PhD, contributed to conception and design; acquisition and analysis and interpretation of the data; and drafting, critical revision, and final approval of the article. Douglas J. Casa, PhD, ATC, FNATA, FACSM, contributed to conception and design; acquisition of the data; and drafting, critical revision, and final approval of the article. Laura J. Burton, PhD, contributed to analysis and interpretation of the data and critical revision and final approval of the article.

References

- 1.Houglum P.A. Redefining our actions to better reflect our profession. J Athl Train. 1998;33(1):13–14. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mazerolle S.M, Bruening J.E. Sources of work-family conflict among certified athletic trainers, part 1. Athl Ther Today. 2006;11(5):33–35. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mazerolle S.M, Bruening J.E. Work-family conflict, part 2: how athletic trainers can ease it. Athl Ther Today. 2006;11(6):47–49. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mazerolle S.M, Bruening J.E, Casa D.J. Work-family conflict part I: antecedents of work-family conflict in National Collegiate Athletic Association Division I-A certified athletic trainers. J Athl Train. 2008;43(5):505–512. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-43.5.505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mazerolle S.M, Bruening J.E, Casa D.J, Burton L, Van Heest J. The impact of work-family conflict on job satisfaction and life satisfaction in Division I-A athletic trainers [abstract] J Athl Train. 2006;41(suppl 2):S-73. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Milazzo S.A, Miller T.W, Bruening J.E, Faghri P.D. A survey of Division I-A athletic trainers on bidirectional work-family conflict and its relation to job satisfaction [abstract] J Athl Train. 2006;41(suppl 2):S-73. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mensch J, Wham G. It's a quality-of-life issue. Athl Ther Today. 2005;10(1):34–35. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pitney W.A. Organizational influences and quality-of-life issues during the professional socialization of certified athletic trainers working in the National Collegiate Athletic Association Division I setting. J Athl Train. 2006;41(2):189–195. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Scriber K.C, Alderman M.M. The challenge of balancing our professional and personal lives. Athl Ther Today. 2005;10(6):14–17. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dixon M.A, Bruening J.E. Work-family conflict in coaching I: a top-down perspective. J Sport Manage. 2007;21(3):377–406. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dixon M.A, Bruening J.E. Perspectives on work-family conflict in sport: an integrated approach. Sport Manage Rev. 2005;8(3):227–253. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Duxbury L, Higgins C, Lee C. Work-family conflict: a comparison by gender, family type, and perceived control. J Fam Iss. 1994;15(3):449–466. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frone M.R, Yardley J.K, Markel K.S. Developing and testing an integrative model of the work-family interface. J Vocation Behav. 1997;50(2):145–167. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frone M.R, Russell M, Cooper M.L. Antecedents and outcomes of work-family conflict: testing a model of the work-family interface. J Appl Psychol. 1992;77(1):65–78. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.77.1.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gutek B.A, Searle S, Klepa L. Rational versus gender role expectations for work-family conflict. J Appl Psychol. 1991;76(4):560–568. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Major V.S, Klein K.J, Ehrhar M.G. Work time, work interference with family, and psychological distress. J Appl Psychol. 2002;87(3):427–436. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.87.3.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Netemeyer R.G, Boles J.S, McMurrian R. Development and validation of work-family conflict and family-work conflict scales. J Appl Psychol. 1996;81(4):400–410. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cooke R.A, Rousseau D.M. Stress and strain from family roles and work-role expectations. J Appl Psychol. 1984;69(2):252–260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boles J.S, Howard G.W, Howard-Donofrio H. An investigation into the inter-relationships of work-family conflict, family-work conflict and work satisfaction. J Manage Iss. 2001;13(3):376–390. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Babin B.J, Boles J.S. The effects of perceived co-worker involvement and supervisor support on service provider roles stress, performance and job satisfaction. J Retail. 1996;72(1):57–75. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kossek E.E, Ozeki C. Work-family conflict, policies, and the job-life satisfaction relationship: a review and directions for organizational behavior-human resources research. J Appl Psychol. 2001;1998;83(2):139–149. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Allen T.D, Herst D.E.L, Bruck C.S, Sutton M. Consequences associated with work-to-family conflict: a review and agenda for future research. J Occup Health Psychol. 2000;5(2):278–308. doi: 10.1037//1076-8998.5.2.278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thomas L.T, Ganster D.C. Impact of family-supportive work variables on work-family conflict and strain: a control perspective. J Appl Psychol. 1995;80(1):6–15. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Adams G.A, King L.A, King D.W. Relationships of job and family involvement, family social support, and work-family conflict with job and life satisfaction. J Appl Psychol. 1996;81(4):411–420. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Greenhaus J.H, Beutell N.J. Sources of conflict between work and family roles. Acad Manage Rev. 1985;10(1):76–88. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dixon M.A, Sagas M. The relationship between organizational support, work-family conflict, and the job-life satisfaction of university coaches. Res Q Exerc Sport. 2007;78(3):236–247. doi: 10.1080/02701367.2007.10599421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barrett J.J, Gillentine A, Lamberth J, Daughtrey C.L. Job satisfaction of NATABOC certified athletic trainer at Division One National Collegiate Athletic Association institutions in Southeastern Conference. Int Sports J. 2002;4(2):1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Capel S.A. Attrition of athletic trainers. Athl Train J Natl Athl Train Assoc. 1990;25(1):34–39. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Member statistics. National Athletic Trainers' Association. www.nata.org/members1/documents/membstats/2005eoy.htm. Accessed April 20, 2005.

- 30.Boles J.S, Babin On the front lines: stress, conflict, and the customer service provider. J Bus Res. 1996;37(1):41–50. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pleck J.H, Staines G.L, Lang L. Conflicts between work and family life. Mon Labor Rev. 1980;103(3):29–32. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rapoport R, Bailyn L, Fletcher J, Pruitt B. Beyond Work-Family Balance. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Capel S.A. Psychological and organizational factors related to burnout in athletic trainers. Athl Train J Natl Athl Train Assoc. 1986;21(4):322–328. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hendrix A.E, Acevedo E.O, Hebert E. An examination of stress and burnout among certified athletic trainers at Division I-A universities. J Athl Train. 2000;35(2):139–144. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Caccese T.M, Mayberburg C.K. Gender differences in perceived burnout of college coaches. J Sport Psychol. 1984;6:279–288. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kalliath T, Morris R. Job satisfaction among nurses: a predictor of burnout levels. J Nurs Admin. 2006;32(12):648–654. doi: 10.1097/00005110-200212000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Henning J.M, Weidner T.G. Contributing factors to role strain in collegiate athletic training Approved Clinical Instructors [abstract] J Athl Train. 2006;41(suppl 2):S-73. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-43.3.275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Survey of men and women in athletic training. Women in Athletic Training Committee. www.nata.org/members1/committees/watc/watc_historywomen/member_surveys.htm. Accessed April 26, 2004.

- 39.Pastore D.L. Male and female coaches of women's athletic teams: reasons for entering and leaving the profession. J Sport Manage. 1991;5(2):128–143. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pastore D.L, Inglis S, Danylchuk K.E. Retention factors in coaching and athletic management: differences by gender, position, and geographic location. J Sport Social Iss. 1996;20(4):427–441. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mazerolle S.M, Casa T.M, Casa D.J. Addressing WFC in the Athletic Training Profession Through High-Quality Discussions. Athl Ther Today. 2008;13(4):5–10. [Google Scholar]