Abstract

The last two steps in the biosynthesis of riboflavin, an essential metabolite that is involved in electron transport, are catalyzed by lumazine synthase and riboflavin synthase. In order to obtain structural probes and inhibitors of these two enzymes, two ribityllumazinediones bearing alkyl phosphate substituents were synthesized. The synthesis involved the generation of the ribityl side chain, the phosphate side chain, and the lumazine system in protected form, followed by the simultaneous removal of three different types of protecting groups. The products were designed as intermediate analog inhibitors of lumazine synthase that would bind to its phosphate-binding site as well as its lumazine binding site. Both compounds were found to be effective inhibitors of both Bacillus subtilis lumazine synthase as well as Escherichia coli riboflavin synthase. Molecular modeling of the binding of one of the two compounds provided a structural explanation for how these compounds are able to effectively inhibit both enzymes. In phosphate-free buffer, the phosphate moieties of the inhibitors were found to contribute positively to their binding to Mycobacterium tuberculosis lumazine synthase, resulting in very potent inhibitors with Ki values in the low nanomolar range. The additional carbonyl in the dioxolumazine system vs. the purinetrione system was found to make a positive contribution to its binding to E. coli riboflavin synthase.

Introduction

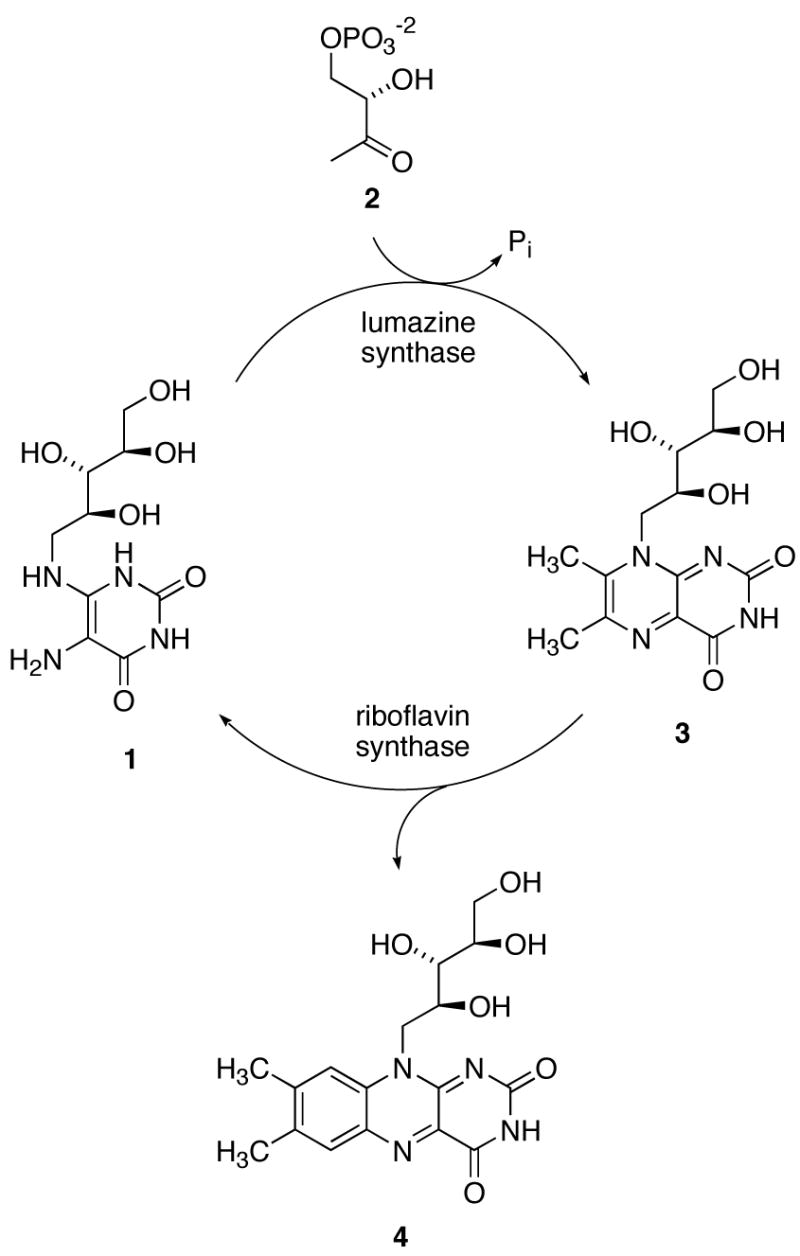

The last two steps in the biosynthesis of riboflavin (Scheme 1) involve the lumazine synthase-catalyzed reaction of the four-carbon phosphate 2 with the ribitylaminopyrimidinedione 1 to form 6,7-dimethyl-8-ribitylumazine (3), followed by the riboflavin synthase-catalyzed dismutation of two molecules of 3 to form one molecule of riboflavin (4) and one molecule of the lumazine synthase substrate 1. In a beautiful example of natural recycling, the product 1 of the riboflavin synthase-catalyzed reaction is then utilized by lumazine synthase. The overall stoichiometry involves the consumption of one molecule of the pyrimidinedione 1 and two molecules of the organophosphate 2 to form one molecule of riboflavin (4).1–5

SCHEME 1.

The mechanism proposed for the lumazine synthase-catalyzed reaction has gone through several iterations, the most recent of which is outlined in Scheme 2.6 The location of the phosphate moiety in the enzyme complex involving the hypothetical intermediate 5, relative to the remainder of the molecule, is roughly approximated as shown in the structure of the initial carbinolamine intermediate 5 as displayed in Scheme 2, as evidenced by the crystal structure of the complex formed between Saccharomyces cerevisiae lumazine synthase and the intermediate analogue 117 (Figure 1).8 Rotation of the whole phosphate-containing side chain toward the ribitylamino moiety would then generate conformer 6, which could eliminate water to form the cis Schiff base 7. Phosphate elimination would lead to the enol 8, followed by tautomerization to the ketone 9. Nucleophilic attack of the ribitylamino group on the ketone would result in the carbinolamine 10, which could eliminate water to form the final product 3.

SCHEME 2.

Figure 1.

Crystal structure of phosphonate 11 bound in the active site of S. cerevisiae lumazine synthase.8 The figure is programmed for walleyed viewing.

Although the pathway outlined in Scheme 2 seems reasonable from a structural and mechanistic point of view, the exact sequence of the events required to form the final product has not been rigorously established. For example, phosphate elimination could occur after Schiff base formation and before the conformational reorganization of the side chain to favor formation of the six-membered ring.9

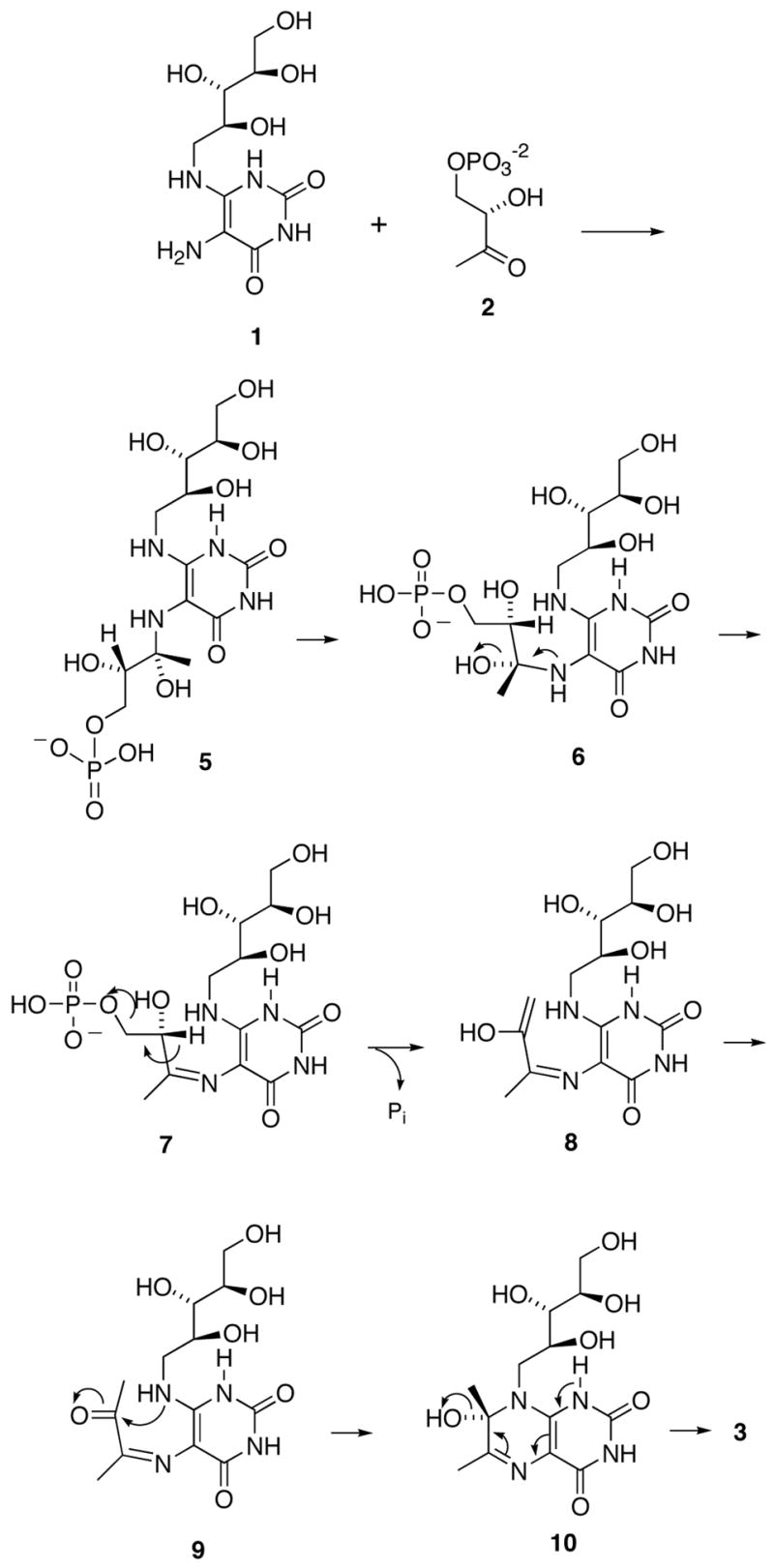

When determined in the presence of fixed substrate 1 concentration and variable substrate 2 concentration, the phosphonate 11 is a moderately active inhibitor of B. subtilis lumazine synthase (mixed inhibition, Ki 180 μM, Kis 350 μM).7 When tested under the same conditions, the purinetrione 12 proved to be more potent, displaying mixed inhibition with a Ki of 46 μM and a Kis of 250 μM.10 The combination of the purinetrione ring system with a C-5 phosphate side chain to form 13 resulted in a less potent inhibitor of B. subtilis lumazine synthase (Ki, 852 μM; Kis, 817 μM) when tested in the presence of variable substrate 2 concentration.11 However, the substituted purinetrione 13 unexpectedly proved to be a very potent competitive inhibitor of Mycobacterium tuberculosis lumazine synthase when tested in Tris buffer (phosphate free) with a Ki of 4.7 nM!11 The selectivity of this compound and its phosphate homologs for the M. tuberculosis enzyme as opposed to the Bacillus subtilis enzyme is truly remarkable. The alkylphosphonate side chain does in fact contribute positively to inhibition of M. tuberculosis lumazine synthase, since the purinetrione system 12 itself is a Ki 9.1 μM inhibitor of the enzyme.11 The alkylphosphonate derivative 13 is also a competitive inhibitor of Escherichia coli riboflavin synthase with a Ki of 2.44 μM.11

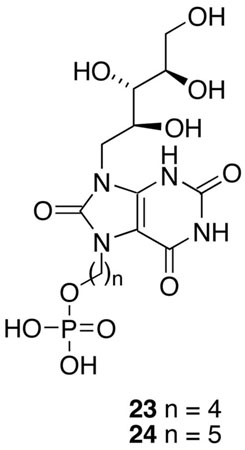

These results suggest consideration of the 6,7-dihydro-6,7-dioxo-8-ribityllumazine system 14, which was previously shown to be an exceedingly potent inhibitor of baker's yeast riboflavin synthase (Ki 25 nM)12 and Ashbya gossypii riboflavin synthase (Ki 9 nM).13 This led to the hypothesis that the attachment of alkylphosphate side chains on N-5 of the 6,7-dioxo-8-ribityllumazine (14) system would likely result in promising inhibitors of E. coli riboflavin synthase as well as M. tuberculosis lumazine synthase. The present communication describes the synthesis and biological testing of the suggested five-carbon and six-carbon alkylphosphate derivatives of 14.

The rationale for the potential medical use of riboflavin synthase inhibitors stems from the fact that certain Gram-negative pathogenic bacteria and yeasts have been shown to lack an efficient riboflavin uptake system and are therefore absolutely dependent on endogenous riboflavin biosynthesis.14–17 In contrast, humans lack riboflavin biosynthesis enzymes and obtain this essential nutrient entirely from dietary sources. Therefore, inhibitors of riboflavin biosynthesis can be expected to display selective cytotoxicity for pathogenic microorganisms as opposed to human cells.

Results and Discussion

The linker from the phosphate to the pyrimidine ring in the proposed reaction intermediate 5 is four atoms long and the results from previous studies on the purinetrione derivative 13 and its homologues revealed that the best linkers between phosphate and purinetrione ring are from three to five atoms long for inhibition of M. tuberculosis lumazine synthase. It was therefore logical to choose the alkylphosphate derivatives of 14 with polymethylene chains containing four and five carbon atoms.11,18

The syntheses of the two phosphates 21 and 22 having four- and five-methylene linker chains between the phosphate and the lumazinedione ring system are outlined in Scheme 3. Since the lumazinedione ring system 14 and the ribityl hydroxyl groups can be alkylated, the synthesis required the generation of these two moieties in protected form before the desired alkylation reaction could be carried out. Starting from the known pyrimidine 1511, catalytic reduction of the nitro group over palladium on carbon yielded an unstable amine intermediate that was reacted immediately with ethyl chlorooxoacetate, followed by heating the intermediate with triethylamine in refluxing ethanol, to provide the pteridine system 16. Reaction of 16 with 1,4-diiodobutane and 1,5-diiodopentane resulted in displacement of one of the iodides from each diiodo compound to afford the desired alkyl iodides 17 and 18. Displacement reactions on the iodides 17 and 18 with silver dibenzyl phosphate resulted in the alkyl phosphates 19 and 20. Simultaneous removal of all three types of protecting groups (TBDMS, methyl, and benzyl) was accomplished by heating intermediates 19 and 20 with HBr in aqueous methanol at 55–60 oC to afford the target compounds 21 and 22 in good yields.

SCHEME 3.

Reagents and conditions: (a) (1) H2, Pd/C, MeOH, 23 oC (3 days); (2) EtOCOCOCl, Et3N, CH2Cl2, 0 oC (10 h); (3) Et3N, EtOH, reflux (72 h). (b) Diiodoalkane, K2CO3, CH3CN, reflux (10 h). (c) AgOPO(OBn)2, CH3CN, reflux (12 h). (d) [48% HBr-H2O (2:1)]-MeOH (1 ; 1), 55-60 oC (3 h).

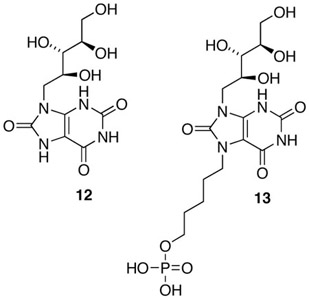

The phosphates 21 and 22 were tested as inhibitors of recombinant B. subtilis lumazine synthase β60 capsids, recombinant E. coli riboflavin synthase, and recombinant M. tuberculosis lumazine synthase. The inhibition constants and inhibition mechanisms for 21 and 22 are listed in Table 1. To evaluate the effect of substitution with the alkylphosphate chains in these compounds, the dioxolumazine system 14 itself was also tested as an inhibitor of all three enzymes, and the previously determined data for the purinetriones 23 and 24 are also listed in Table 1 for comparison.11 Representative Lineweaver-Burke plots for inhibition of B. subtilis lumazine synthase, M. tuberculosis lumazine synthase, and E. coli riboflavin synthase by inhibitor 22 are presented in Figure 2.

TABLE 1.

Inhibition Constants vs. B. subtilis Lumazine Synthase, M. tuberculosis Lumazine Synthase and E. coli Riboflavin Synthase.

| Compd | Parameter | Lumazine synthase | Riboflavin synthase | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B. subtilisa | M. tuberculosisb | E. colic | ||

| 14 | inhibition mechanism | competitive | competitive | competitive |

| Ksd (μM) | 6.3 ± 0.5 | 250 ± 43 | 2.7 ± 0.2 | |

| kcate (min−1) | 2.6 ± 0.1 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 15.0 ± 0.3 | |

| Kif (μM) | 7.8 ± 0.5 | 1.4 ± 0.1 | 0.0062 ± 0.0005 | |

| 21 | inhibition mechanism | mixed | competitive | mixed |

| Ks (μM) | 7.1 ± 1.0 | 240 ± 29 | 2.5 ± 0.3 | |

| kcat (min−1) | 2.1 ± 0.1 | 1.2 ± 0.1 | 15.0 ± 0.4 | |

| Ki (μM) | 150 ± 43 | 0.036 ± 0.004 | 9.7 ± 4.1 | |

| Kisg (μM) | 400 ± 130 | 21 ± 5 | ||

| 22 | inhibition mechanism | competitive | competitive | competitive |

| Ks (μM) | 5.8 ± 0.4 | 210 ± 28 | 2.9 ± 0.4 | |

| kcat (min−1) | 2.7 ± 0.1 | 0.99 ± 0.07 | 14 ± 1 | |

| Ki (μM) | 27 ± 6 | 0.012 ± 0.004 | 0.14 ± 0.02 | |

| 23 | inhibition mechanism | competitive | competitive | competitive |

| Ks (μM) | 3.2 ± 0.4 | 63 ± 6 | 2.1 ± 0.2 | |

| kcat (min−1) | 3.1 ± 0.1 | 1.4 ± 0.1 | 17.0 ± 0.4 | |

| Ki (μM) | 170 ± 26 | 0.0041 ± 0.0023 | 330 ± 83 | |

| 24 | inhibition mechanism | mixed | competitive | competitive |

| Ks (μM) | 3.8 ± 0.4 | 63 ± 5 | 2.0 ± 0.2 | |

| kcat (min−1) | 3.15 ± 0.10 | 1.40 ± 0.04 | 17.0 ± 0.4 | |

| Ki (μM) | 270 ± 85 | 0.0047 ± 0.0019 | 2.4 ± 0.2 | |

| Kis (μM) | 650 ± 160 | |||

Recombinant lumazine synthase of B. subtilis.

Recombinant lumazine synthase from M. tuberculosis.

Recombinant riboflavin synthase from E. coli.

Ks is the substrate dissociation constant for the equilibrium E + S ⇄ES.

kcat is the rate constant for the process ES → E + P.

Ki is the inhibitor dissociation constant for the process E + I ⇄ EI.

Kis is the inhibitor dissociation constant for the process ES + I ⇄ESI. Ki values of less than 1 μM are shown in bold type.

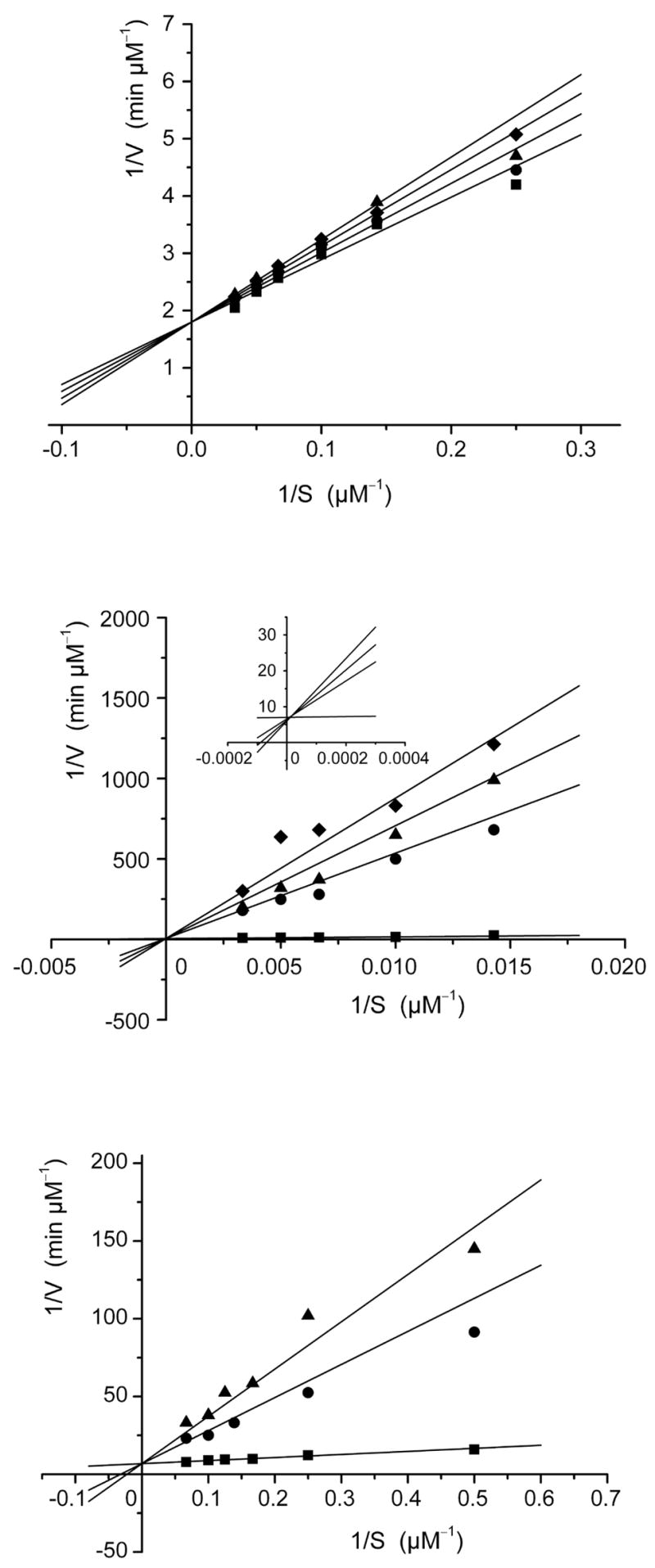

Figure 2.

Lineweaver-Burke plots for the inhibition of B. subtilis lumazine synthase by inhibitor 22 (top: inhibitor concentrations 0, 3.0, 6.0, and 8.6 μM, mechanism: competitive), M. tuberculosis lumazine synthase (center: inhibitor concentrations 0, 0.8, 1.0, and 1.2 μM, mechanism: competitive), and E. coli riboflavin synthase (bottom: inhibitor concentrations 0, 1.5, and 2.0 μM, mechanism: competitive). The inset in the M. tuberculosis plot (middle) shows an expanded view of the simulation plot in the region 1/S = 0. The kinetic data were fitted with a nonlinear regression method using the program Dynafit from P. Kuzmic (1996). Different kinetic models were considered, and the most likely inhibition mechanism was determined to be competitive inhibition in each case.

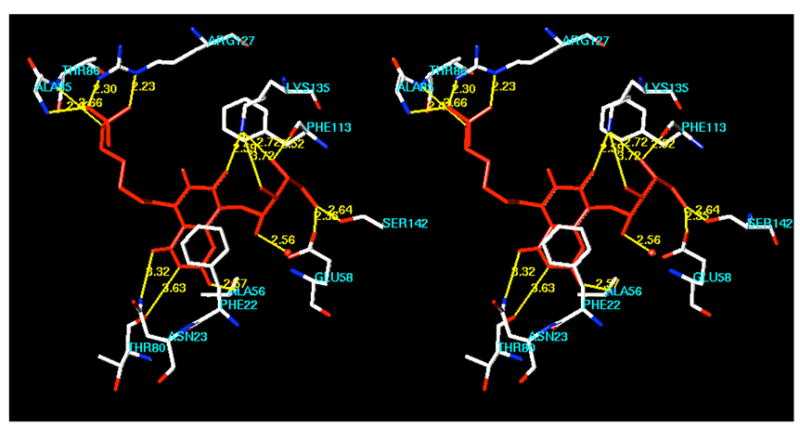

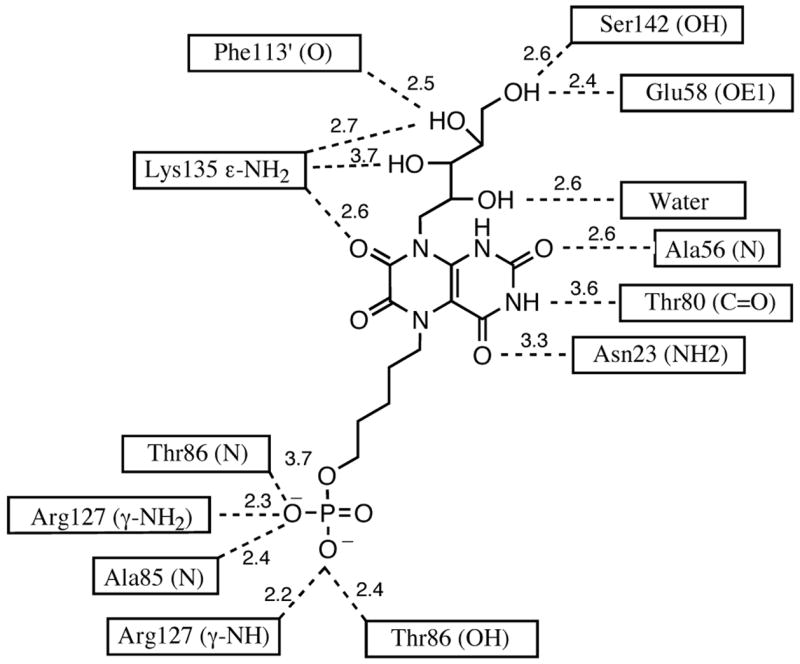

Crystal structures are now available for complexes formed between the substrate analogue 25 and the lumazine synthases of B. subtilis and S. pombe.19,20 The X-ray structure of the intermediate analogue 11 bound to S. cerevisiae lumazine synthase (Figure 1),8 the product analogue 26 bound to S. pombe lumazine synthase, 20 and the intermediate analogue inhibitor 23 and its lower homologue bound to M. tuberculosis lumazine synthase all allow the rational docking and energy minimization of additional lumazine synthase inhibitors to create hypothetical structures of their enzyme complexes. In the present case, a molecular model was constructed by overlapping the structure of 22 with that of 25 in a 15 Å spherical fragment surrounding the ligand in one of the sixty equivalent active sites of B. subtilis lumazine synthase. The structure of 25 was then deleted and the energy of the complex minimized using the MMFF94s force field and MMFF94 charges while allowing the ligand and the protein structure contained within a 6 Å sphere surrounding the ligand to be flexible and the remainder of the protein structure immobile. The resulting structure is displayed in Figure 3, which shows the bound ligand 22 (red) and the surrounding amino acid residues of the protein that are calculated to be involved in hydrogen bonding (yellow lines) to the ligand. The calculated structure of the complex shows the expected stacking of the lumazinedione ring system of the ligand with the benzene ring of Phe22. There is extensive bonding of the phosphate moiety with the side chain nitrogens of Arg127, the side chain hydroxyl of Thr86, and the backbone nitrogens of Thr86 and Ala85. The imide fragment of the heterocyclic system has contacts with the backbone nitrogen of Ala56, the backbone carbonyl of Thr80, and the side chain nitrogen of Asn23. The side chain nitrogen of Lys135 is calculated to play a strong role in stabilizing the complex, with possible hydrogen bonding contacts with the C-7 carbonyl of the heterocyclic system of the ligand as well as with the 3'- and 4'-hydroxyl groups. A water molecule hydrogen bonds to the 2'-hydroxyl group of the ribityl moiety, and the 4'-hydroxyl group hydrogen bonds to the side chain carbonyl of Phe113'. The 5'-hydroxyl group is calculated to bond to the side chain hydroxy group of Ser142 and the carboxyl of Glu58. All of the calculated hydrogen bonds and distances are displayed in Figure 4.

Figure 3.

Hypothetical model for the binding of compound 22 to Bacillus subtilis lumazine synthase. The figure is programmed for walleyed viewing.

Figure 4.

Hydrogen bonds and distances in the calculated model of the inhibitor 22 bound in the active site of B. subtilis lumazine synthase.

New antibiotics that are active against drug-resistant M. tuberculosis are needed urgently. Therefore, the phosphates 21 and 22, as well as the parent compound 14, were tested as inhibitors of M tuberculosis lumazine synthase. Both of the phosphates 21 (Ki 0.036 μM) and 22 (Ki 0.012 μM), like 23 and 24, proved to be very potent inhibitors with Ki values in the low nanomolar range. Interestingly, the attachment of the phosphate chains to the lumazinedione 14 caused a dramatic increase in potency vs. M. tuberculosis lumazine synthase (compare 14 vs. 21 and 22). This is in contrast to the results seen with the B. subtilis enzyme, where decreases in potency resulted from side chain attachment when tested in the presence of variable substrate 1 concentration. As with the B. subtilis enzyme, the increase in the side chain length resulted in a modest increase in potency vs. M. tuberculosis lumazine synthase (compare 21 vs. 22). However, both 21 and 22 appeared to be slightly less active vs. M. tuberculosis lumazine synthase than 23 and 24. All of the compounds tested proved to be competitive inhibitors of M. tuberculosis lumazine synthase.

The purinetrione system 12 can be considered to be a product analog of lumazine synthase and a substrate analog of riboflavin synthase. Accordingly, it was previously tested as an inhibitor of both enzymes and found to be a Ki 46 μM inhibitor of B. subtilis lumazine synthase (with variable 2concentration) and a 0.61 μM inhibitor of E. coli riboflavin synthase.10 However, unexpectedly, the phosphate derivatives 23 and 24 also proved to be riboflavin synthase inhibitors.11 Accordingly, both lumazindione derivatives 21 and 22 were tested vs. E. coli riboflavin synthase. Compound 21 was a mixed inhibitor with Ki 9.7 μM and Kis 21 μM, while 22 was a competitive inhibitor with Ki 0.14 μM. This documents a significant effect of chain length on potency, and it is similar to the effect seen with the purinetriones 23 and 24. However, both of the lumazinedione phosphate derivatives 21 and 22 were much less active that the lumazinedione system 14 itself (Ki 0.0062 μM), so the attachment of the phosphate side chains to these molecules causes a significant drop in potency vs. E. coli riboflavin synthase. One of the reasons for originally conducting this study was to test the hypothesis that the pyrimidinediones 21 and 22 would be more potent as riboflavin synthase inhibitors than the purinetriones 23 and 24, and the results indicate that they in fact are more potent inhibitors. The additional carbonyl group present in 21 and 22 therefore does have a significantly positive effect on the riboflavin synthase enzyme inhibitory activity that is also reflected in the parent compounds 12 (Ki 0.61 μM) and 14 (Ki 0.0062 μM).

The crystal structure of E. coli riboflavin synthase, which contains three identical subunits, has been published along with a hypothetical model of bound substrate 3.21 A crystal structure has also been determined of monomeric S. pombe riboflavin synthase with bound substrate analogue 26,22 and an NMR investigation of the structure of the N-terminal domain of riboflavin synthase has also appeared.23 The studies have established that the active site of riboflavin synthase is derived from the intermolecular juxtaposition of residues belonging to both of the barrels in the C-terminal and N-terminal domains of two subunits, with one substrate molecule bound to each barrel. Thus, structures are available for the trimeric apoenzyme and a ligand-bound monomer, and the structures of the active site can be proposed by combining elements of the two structures. The structures allow the molecular modeling of the complex formed between E. coli riboflavin synthase and the inhibitor 22 using a similar procedure as described for modeling with lumazine synthase, and the result is displayed in Figure 5. The C-barrel in Figure 5 is colored magenta and the N-barrel is green. The two ligand molecules are stacked with their ribityl side chains pointing in opposite directions, which is consistent with both the known regiochemistry of the riboflavin synthase-catalyzed reaction and the available crystal structures.3 This means that the two phosphate side chains must also be pointing in opposite directions. Overall, the structure indicates that riboflavin synthase could in fact accommodate two molecules of the inhibitor 22 in the active site.

Figure 5.

Hypothetical model of the binding of two molecules of inhibitor 22 to E. coli riboflavin synthase. The C-barrel is magenta and the N-barrel is green. The model is programmed for walleyed viewing.

In conclusion, two alkyl phosphate derivatives of the 6,7-dihydro-6,7-dioxo-8-ribityllumazine system were synthesized and found to be inhibitors of B. subtilis and M. tuberculosis lumazine synthase as well as E. coli riboflavin synthase. The possible binding modes of these compounds were investigated through molecular modeling of complexes formed between compound 22 and both lumazine synthase and riboflavin synthase. Potential antibiotics that inhibit both lumazine synthase and riboflavin synthase would have a potential therapeutic advantage over those that inhibit only one enzyme because microorganisms would have to mutate both enzymes at the same time in order to acquire drug resistance.

Experimental Section

General

Melting points were determined in capillary tubes and are uncorrected. Proton nuclear magnetic resonance spectra (1H NMR) were determined at 300 MHz or at 500 MHz as noted. Silica gel used for column chromatography was 230–400 mesh.

8-(2′,3′,4′,5′-tetrakis-t-butyldimethylsilyl-D-ribityl)-5,6,7,8-tetrahydro-2,4-dimethoxy-6,7-dioxopteridine (16)

The nitro compound 15 (4.21g, 5.32 mmol) was dissolved in methanol (150 mL) and palladium on charcoal (10%, 500 mg) was added. The reaction mixture was hydrogenated at room temperature and 1 atm for 3 days. The catalyst was filtered off, the filtrate was concentrated to remove the solvent completely, and the residue was dried well under vacuum. Triethylamine (2.2 mL, 16 mmol) and dichloromethane (30 mL) were added and the reaction mixture was cooled to 0 oC. A solution of ethyl oxalyl chloride (0.6 mL, 5.32 mmol) in dichloromethane (10 mL) was added dropwise and the mixture was stirred overnight at RT. The reaction mixture was washed with water (2 x 20 mL), dried with anhydrous Na2SO4, filtered, and concentrated under vacuum. The residue was dissolved in absolute ethanol (150 mL) and TEA (20 mL) and heated at reflux for 72 h. The solvent was removed under reduced pressure and the residue was purified by flash chromatography (silica gel, 50 g, 230–400 mesh), eluting with hexane-ethyl acetate (1:1), to furnish pure 16 (1.55 g, 36%) as a foamy solid. 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.52 (s, 1 H), 5.05 (dd, J = 9.9 Hz, J = 13.15 Hz, 1 H), 4.47 (d, J = 9.9 Hz, 1 H), 4.38 (dd, J = 2.49 Hz, J = 13.1 Hz, 1 H), 4.12 (s, 3 H), 4.05 (t, J = 2.13 Hz, 1 H), 4.01 (s, 3 H), 3.84 (m, 1 H), 3.72 (m, 1 H), 3.60 (dd, J = 6.03 Hz, J = 9.64 Hz, 1 H), 0.97 (s, 9 H), 0.90 (s, 9 H), 0.89 (s, 9 H), 0.64 (s, 9 H), 0.19 (s, 3 H), 0.14 (s, 3 H), 0.12 (s, 9 H), 0.07 (s, 3 H), 0.06 (s, 3 H), −0.02 (s, 3 H); IR (KBr) 2954, 2957, 1713, 1603, 1472, 1488, 1378, 1254, 1103, 834 cm−1; EIMS m/z 815 (MH+). Anal. Calcd for C37H74N4O4Si8: C, 54.50; H, 9.15; N, 6.87. Found: C, 54.50; H, 9.16; N, 6.67 .

8-(2′,3′,4′,5′-Tetrakis-t-butyldimethylsilyl-D-ribityl)-5,6,7,8-tetrahydro-5-(4′-iodobutyl)-2,4-dimethoxy-6,7-dioxopteridine (17)

Compound 16 (300 mg, 0.37 mmol) was dissolved in dry CH3CN (20 mL). Anhydrous K2CO3 (200 mg, 1.45 mmol) and 1,4-diiodobutane (0.24 mL, 1.84 mmol) were added, and the mixture was heated at reflux overnight. The mixture was filtered and the solvent was removed under reduced pressure. The residue was purified by flash chromatography (SiO2, 230–400 mesh) (elution: hexane-EtOAc 95:5) to afford pure 17 (234 mg, 63.0%) as colorless oil. 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ 5.08 (dd, J = 10.09 Hz, J = 13.06 Hz, 1 H), 4.42 (d, J = 9.79 Hz, 1 H), 4.34 (t, J = 9.41 Hz, 3 H), 4.09 (s, 3 H), 4.07 (d, J = 13.3 Hz, 1 H), 3.98 (s, 3 H), 3.84 (t, J = 6.48 Hz, 1 H), 3.69 (dd, J = 7.23 Hz, J = 17.95 Hz, 1 H), 3.58 (dd, J = 6.03 Hz, J = 10.56 Hz, 1 H), 3.21 (t, J = 6.46 Hz, 2 H), 1.88 (quint, J = 7.21 Hz, 2 H), 1.82 (quint, J = 7.21 Hz, 2 H), 0.94 (s, 9 H), 0.87 (s, 9 H), 0.86 (s, 9 H), 0.62 (s, 9 H), 0.16 (s, 3 H), 0.12 (s, 3 H), 0.09 (s, 6 H), 0.043 (s, 3 H), 0.036 (s, 3 H), −0.055 (s, 3 H), −0.49 (s, 3 H). EIMS m/z 997 (MH+). Anal. Calcd for C41H81IN4O8Si4: C, 49.37; H, 8.19; N, 5.62. Found: C, 49.21; H, 8.38; N, 5.27.

8-(2′,3′,4′,5′-Tetrakis-t-butyldimethylsilyl-D-ribityl)-5,6,7,8-tetrahydro-5-(5′-iodopentyl)-2,4-dimethoxy-6,7-dioxopteridine (18)

Compound 16 (250 mg, 0.31 mmol) was dissolved in dry CH3CN (10 mL). Anhydrous K2CO3 (200 mg, 1.45 mmol) and 1,5-diiodopropane (0.24 mL, 1.53 mmol) were added, and the mixture was heated at reflux overnight. The mixture was filtered and the solvent was removed under reduced pressure. The residue was purified by flash chromatography (SiO2, 230-400 mesh) (elution: hexane-EtOAc 95:5) to afford pure 18 (211 mg, 68.0%) as a colorless oil. 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 5.08 (dd, J = 10.14 and 13.01 Hz, 1 H), 4.42 (d, J = 9.78 Hz, 1 H), 4.31 (t, J = 9.41 Hz, 3 H), 4.08 (s, 3 H), 4.05 (d, J = 11.0 Hz, 1 H), 3.98 (s, 3 H), 3.84 (t, J = 5.9 Hz, 1 H), 3.69 (dd, J = 7.23 and 17.95 Hz, 1 H), 3.58 (dd, J = 6.06 and 10.56 Hz, 1 H), 3.18 (t, J = 6.82 Hz, 2 H), 1.85 (quint, J = 7.21 Hz, 2 H), 1.69 (quint, J = 7.21 Hz, 2 H), 1.48 (quint, J = 7.21 Hz, 2 H), 0.94 (s, 9 H), 0.87 (s, 9 H), 0.86 (s, 9 H), 0.62 (s, 9 H), 0.16 (s, 3 H), 0.12 (s, 3 H), 0.09 (s, 6 H), 0.043 (s, 3 H), 0.036 (s, 3 H), −0.057 (s, 3 H), −0.49 (s, 3 H); EIMS m/z 1011 (MH+). Anal. Calcd for C42H83IN4O8Si4: C, 49.88; H, 8.27; N, 5.54. Found: C, 49.79; H, 7.85; N, 5.46.

Dibenzyl 4-[8-(2′,3′,4′,5′-Tetrakis-t-butyldimethylsilyl-D-ribityl)-5,6,7,8-tetrahydro-2,4-dimethoxy-6,7-dioxopterid-5-yl]butane 1-Phosphate (19)

Compound 17 (0.10 g, 0.10 mmol) and silver dibenzyl phosphate (0.06 g, 0.15 mmol) were heated at reflux in dry CH3CN (5.0 mL) for 10 h. The solution was then filtered and concentrated under reduced pressure. The resulting oil was purified by silica gel flash chromatography (SiO2, 230-400 mesh) eluting with hexane-ethyl acetate (1:1), to furnish the desired compound 19 (0.08 g, 70%) as a colorless oil.1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.31 (s, 10 H), 5.07 (dd, J = 10.09 and 13.06 Hz, 1 H), 4.99 (m, 4 H), 4.41 (d, J = 9.41 Hz, 1 H), 4.33 (d, J = 13.15 Hz, 1 H), 4.26 (t, J = 6.75 Hz, 2 H), 3.99 (q, J = 6.04 Hz, 2 H), 3.98 (s, 3 H), 3.97 (s, 3 H), 3.83 (t, J = 6.45 Hz, 1 H), 3.68 (t, J = 8.82 Hz, 1 H), 3.57 (dd, J = 5.99 and 10.33 Hz, 1 H), 1.67-1.66 (m, 4 H), 0.93 (s, 9 H), 0.87 (s, 9 H), 0.86 (s, 9 H), 0.60 (s, 9 H), 0.15 (s, 3 H), 0.11 (s, 3 H), 0.087 (s, 6 H), 0.038 (s, 3 H), 0.032 (s, 3 H), −0.07 (s, 3 H), −0.52 (s, 3 H); EIMS m/z 1147 (MH+). Anal. Calcd for C55H95N4O12PSi4: C, 57.56; H, 8.34; N, 4.88. Found: C, 57.33; H, 8.40; N, 5.28.

Dibenzyl 4-[8-(2′,3′,4′,5′-Tetrakis-t-butyldimethylsilyl-D-ribityl)5,6,7,8-tetrahydro-2,4-dimethoxy - 6, 7 - dioxopterid - 5-yl] pentane 1 - Phosphate (20)

Compound 18 (0.21 g, 0.21 mmol) and silver dibenzyl phosphate (0.12 g, 0.31 mmol) were heated at reflux in dry CH3CN (10 mL) for 10 h. The solution was then filtered and concentrated under reduced pressure. The resulting oil was purified by using silica gel flash chromatography (SiO2, 230-400 mesh), eluting with hexane-ethyl acetate (1:1), to furnish the desired compound 20 (0.17 g, 71%) as colorless oil. 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.32 (s, 10 H), 5.08 (dd, J = 10.07 and 13.06 Hz, 1 H), 5.01 (m, 4 H), 4.41 (d, J = 9.87 Hz, 1 H), 4.33 (d, J = 13.17 Hz, 1 H), 4.25 (t, J = 7.72 Hz, 2 H), 4.00 (s, 3 H), 3.97 (q, J = 6.04 Hz, 2 H), 3.96 (s, 3 H), 3.84 (t, J = 5.79 Hz, 1 H), 3.69 (t, J = 8.82 Hz, 1 H), 3.58 (dd, J = 5.99 and 10.33 Hz, 1 H), 1.65-1.63 (m, 4 H), 1.53 (m, 2 H), 0.94 (s, 9 H), 0.87 (s, 9 H), 0.86 (s, 9 H), 0.61 (s, 9 H), 0.16 (s, 3 H), 0.11 (s, 3 H), 0.092 (s, 6 H), 0.043 (s, 3 H), 0.038 (s, 3 H), −0.061 (s, 3 H), −0.51 (s, 3 H); EIMS m/z 1161 (MH+). Anal. Calcd for C56H97N4O12PSi4: C, 57.93; H, 8.36; N, 4.82. Found: C, 57.79; H, 8.06; N, 4.84.

4-(1,5,6,7-Tetrahydro-6,7-dioxo-8-D-ribityllumazin-5-yl)butane 1-Phosphate (21)

Compound 19 (82 mg, 0.07 mmol) was dissolved in a solution of [48% HBr-H2O (2:1)]-MeOH (1:1; 5 mL) and the mixture was stirred at 55–60 oC for 3 h. The solvent was removed in vacuo, the residue was dissolved in MeOH (1 mL), and ethyl ether (5 mL) was added. After 24 h in the refrigerator, the precipitate was filtered out as a white solid, which was dissolved in water (5 mL), decolorized with active charcoal and filtered. The colorless filtrate was lyophilized to furnish 21 (25 mg, 73%) as a white, highly hygroscopic amorphous solid. 1H NMR (D2O) (300 MHz) δ 3.41–4.27 (m, 11 H), 1.45 (m, 4 H); 13C NMR (D2O) (75 MHz) δ 158.7, 156.7, 154.5, 149.9, 137.8, 100.6, 76.4, 73.0, 72.4, 71.6, 70.1, 49.2, 45.8, 26.2, 24.9; ESIMS (negative ion mode) m/z 481 [(M – H+)−]. Anal. Calcd for C15H23N4O12P.0.6H2O: C, 36.50; H, 4.91; N, 11.35. Found: C, 36.84; H, 4.71; N, 10.92.

5-(1,5,6,7-Tetrahydro-6,7-dioxo-8-D-ribityllumazin-5-yl)pentane 1-Phosphate (22)

This compound was prepared from 20 in 78% yield using the procedure above to afford the product as a white, highly hygroscopic amorphous solid (38 mg, 78%). 1H NMR (D2O) (300 MHz) δ 3.64-4.58 (m, 11 H), 1.75 (m, 4 H), 1.52 (m, 2 H);13C NMR (D2O) (75 MHz) δ 158.7, 156.8, 154.5, 150.0, 137.9, 100.6, 73.0, 72.4, 70.1, 66.6, 62.8, 47.0, 46.1, 29.6, 27.9, 22.4; ESIMS m/z 495 [(M – H+)−]. Anal. Calcd for C16H25N4O12P.0.5H2O: C, 37.99; H, 5.14; N, 11.08. Found: C, 37.98; H, 4.85; N, 10.73.

Molecular Modeling on Lumazine Synthase

Using Sybyl (Tripos, Inc., version 7.0, 2004), the X-ray crystal structure of the complex of 5-nitro-6-ribitylamino-2,4-(1H,3H)pyrimidinedione (25) and the lumazine synthase of B. subtilis (1RVV)19 was clipped to include information within a 15 Å-radius of one of the 60 equivalent ligand molecules. The residues that were clipped in this cut complex were capped with either neutral amino or carboxyl groups. The structure of the inhibitor 22 was overlapped with the structure of 5-nitro-6-ribitylamino-2,4-(1H,3H)pyrimidinedione (25), which was then deleted. Hydrogen atoms were added to the complex. MMFF94 charges were loaded, and the energy of the complex was minimized using the Powell method to a termination gradient of 0.05 kcal/mol while employing the MMFF94s force field. During the minimization of the complex, inhibitor 22 and 6 Å sphere surrounding it were allowed to remain flexible, while the remaining portion of the complex was held ridged using the aggregate function. Figure 3 was constructed by displaying the amino acid residues of the enzyme that are involved in hydrogen bonding with the inhibitor 22.

Molecular Modeling on Riboflavin Synthase

Using Sybyl (Tripos, Inc., version 7.0, 2004), the X-ray crystal structure of E. coli riboflavin synthase (1I8D) was downloaded and two molecules of the ligand 22 were docked and oriented as suggested by the published model of the binding of two molecules of the substrate 1 in the active site,21 as well as by the structure of 22 bound to S. pombe riboflavin synthase.22 The C- and N-terminal groups were changed to neutral carboxylic acid and amino groups, and hydrogens were added to the protein structure and to the oxygens of the water molecules. MMFF94 charges were loaded, and the energy of a 6 Å-radius spherical subset including and surrounding the two ligand molecules was minimized using the Powell method to a termination gradient of 0.05 kcal/mol while employing the MMFF94s force field. During energy minimization, the remaining protein structure was held rigid using the aggregate function. Figure 5 was constructed by displaying the amino acid residues in the C- and N-barrels surrounding the two ligand molecules.

Lumazine Synthase Assay.24

The experiments with B. subtilis lumazine synthase were performed as follows. Reaction mixtures contained 100 mM potassium phosphate, pH 7.0, 5 mM EDTA, 5 mM dithiothreitol, inhibitor (0–500 μM), 150 μM L-3,4-hihydroxy-2-butanone phosphate (2) and B. subtilis lumazine synthase (7 μg, specific activity 12.8 μmol mg−1 h−1) in a total volume of 1000 μL. The solution was incubated at 37 °C, and the reaction was started by the addition of a small volume (20 μL) of 5-amino-6-ribitylamino-2,4(1H,3H)-pyrimidinedione (1) to a final concentration of 5–100 μM. The experiments with M. tuberculosis lumazine synthase were conducted as follows. Reaction mixtures contained 50 mM Tris hydrochloride, pH 7.0, 100 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 5 mM dithiothreitol, 150 μM L-3,4-hihydroxy-2-butanone phosphate (2) inhibitor (0–500 μM) and M. tuberculosis enzyme (12.5 μg, specific activity 4.3 μmol mg−1 h−1) in a total volume of 1000 μL. The mixtures were incubated at 37 °C, and the reaction was started by the addition of a small volume (20 μL) of substrate 1 to a final concentration of 20−400 μM. The formation of 6,7-dimethyl-8-ribityllumazine (3) was measured online with a computer controlled photometer at 408 nm (εLumazine = 10200 M−1cm−1). The velocity-substrate data were fitted for all inhibitor concentrations with a non- linear regression method using the program DynaFit™ 25 Different inhibition models were considered for the calculation. K i and Kis values ± standard deviations were obtained from the fit under consideration of the most likely inhibition model.

Riboflavin Synthase Assay.26

Reaction mixtures contained buffer (100 mM potassium phosphate, pH 7.0, 10 mM EDTA, 10 mM sodium sulfite), inhibitor (0 to 300 μM), and riboflavin synthase (1.2 μg, specific activity 45 μmol mg−1h−1). After preincubation, the reactions were started by the addition of various amounts of 6,7-dimethyl-8-ribityllumazine (3) (2.5 to 200 μM) to a total volume of 1000 μL. The formation of riboflavin (4) was measured online with a computer controlled photometer at 470 nm (εRiboflavin = 9600 M−1cm−1). The evaluation of data sets was performed in the same manner as described above.

Acknowledgments

This research was made possible by NIH grant GM51469 as well as by support from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, the Fonds der Chemischen Industrie and the Hans Fischer Gesellschaft e. V.

References

- 1.Plaut GWE, Smith CM, Alworth WL. Ann Rev Biochem. 1974;43:899–922. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.43.070174.004343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Plaut GWE. In: Comprehensive Biochemistry. Florkin M, Stotz EH, editors. Vol. 21. Elsevier; Amsterdam: 1971. pp. 11–45. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beach RL, Plaut GWE. J Am Chem Soc. 1970;92:2913–2916. doi: 10.1021/ja00712a052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bacher A, Eberhardt S, Richter G. In: Escherichia coli and Salmonella: Cellular and Molecular Biology. 2. Neidhardt FC, editor. ASM Press; Washington, D. C: 1996. pp. 657–664. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bacher A, Fischer M, Kis K, Kugelbrey K, Mörtl S, Scheuring J, Weinkauf S, Eberhardt S, Schmidt-Bäse K, Huber R, Ritsert K, Cushman M, Ladenstein R. Biochem Soc Trans. 1996;24:89–94. doi: 10.1042/bst0240089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang X, Meining W, Cushman M, Haase I, Fischer M, Bacher A, Ladenstein R. J Mol Biol. 2003;328:167–182. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00186-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cushman M, Mihalic JT, Kis K, Bacher A. J Org Chem. 1999;64:3838–3845. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meining W, Mörtl S, Fischer M, Cushman M, Bacher A, Ladenstein R. J Mol Biol. 2000;299:181–197. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Volk R, Bacher A. J Am Chem Soc. 1988;110:3651–3653. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cushman M, Yang D, Kis K, Bacher A. J Org Chem. 2001;66:8320–8327. doi: 10.1021/jo010706r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cushman M, Sambaiah T, Jin G, Illarionov B, Fischer M, Bacher A. J Org Chem. 2004;69:601–612. doi: 10.1021/jo030278k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Al-Hassan SS, Kulick RJ, Livingston DB, Suckling CJ, Wood HCS, Wrigglesworth R, Ferone R. J Chem Soc, Perkin Trans. 1;1980:2645–2656. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Winestock CH, Aogaichi T, Plaut GWE. J Biol Chem. 1963;238:2866–2874. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang A. I Chuan Hsueh Pao. 1992;19:362–368. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oltmanns O, Lingens F. Z Naturforschung. 1967;22:751–754. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Logvinenko EM, Shavlovsky GM. Mikrobiologiya. 1967;41:978–979. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Neuberger G, Bacher A. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1985;127:175–181. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(85)80141-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morgunova K, Meining W, Illarionov B, Haase I, Jin G, Bacher A, Cushman M, Fischer M, Ladenstein R. Biochemistry. 2005;44:2746–2758. doi: 10.1021/bi047848a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ritsert K, Huber R, Turk D, Ladenstein R, Schmidt-Bäse K, Bacher A. J Mol Biol. 1995;253:151–167. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1995.0542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gerhardt S, Haase I, Steinbacher S, Kaiser JT, Cushman M, Bacher A, Huber R, Fischer M. J Mol Biol. 2002;318:1317–1329. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)00116-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liao DI, Wawrzak Z, Calabrese JC, Viitanen PV, Jordan DB. Structure. 2001;9:399–408. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(01)00600-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gerhardt S, Schott AK, Kairies N, Cushman M, Illarionov B, Eisenreich W, Bacher A, Huber R, Steinbacher S, Fischer M. Structure. 2002;10:1371–1381. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(02)00864-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Truffault V, Coles M, Diericks T, Abelmann K, Eberhardt S, Lüttgen H, Bacher A, Kessler H. J Mol Biol. 2001;309:949–960. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kis K, Bacher A. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:16788–16795. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.28.16788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kuzmic P. Anal Biochem. 1996;237:260–273. doi: 10.1006/abio.1996.0238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eberhardt S, Richter G, Gimbel W, Werner T, Bacher A. Eur J Biochem. 1996;242:712–718. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1996.0712r.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]