Abstract

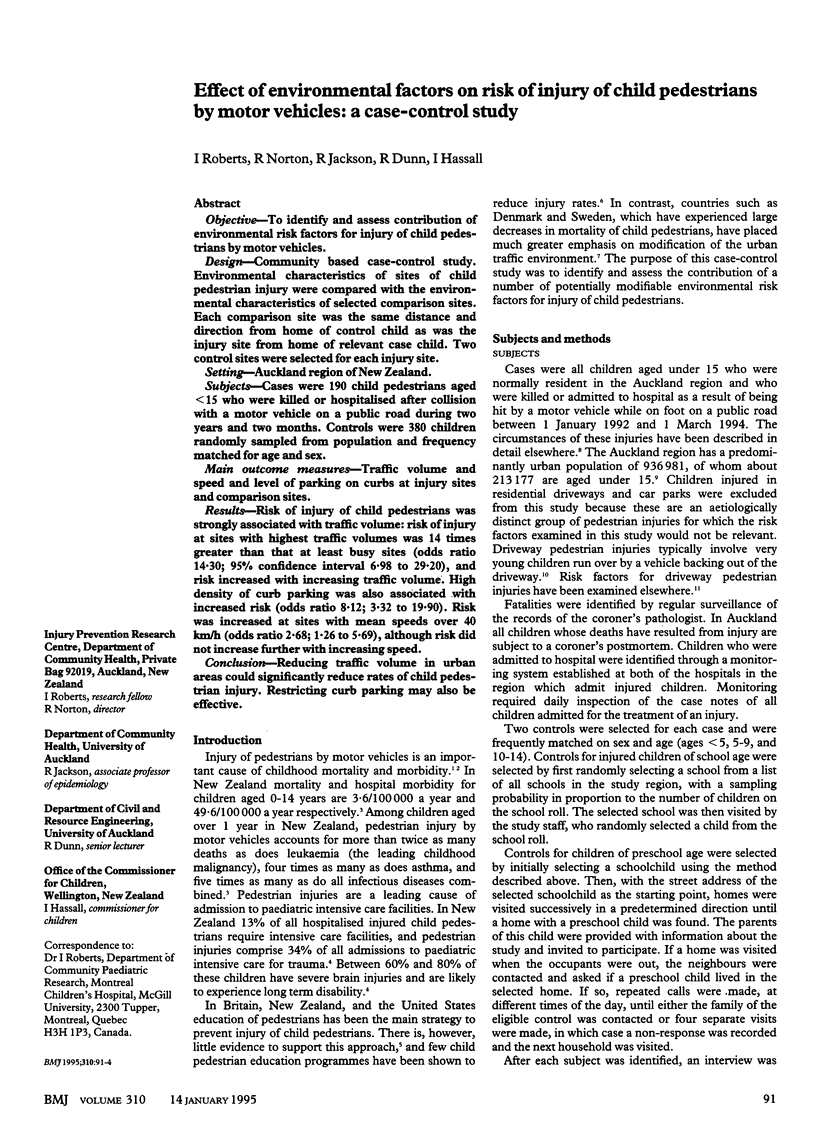

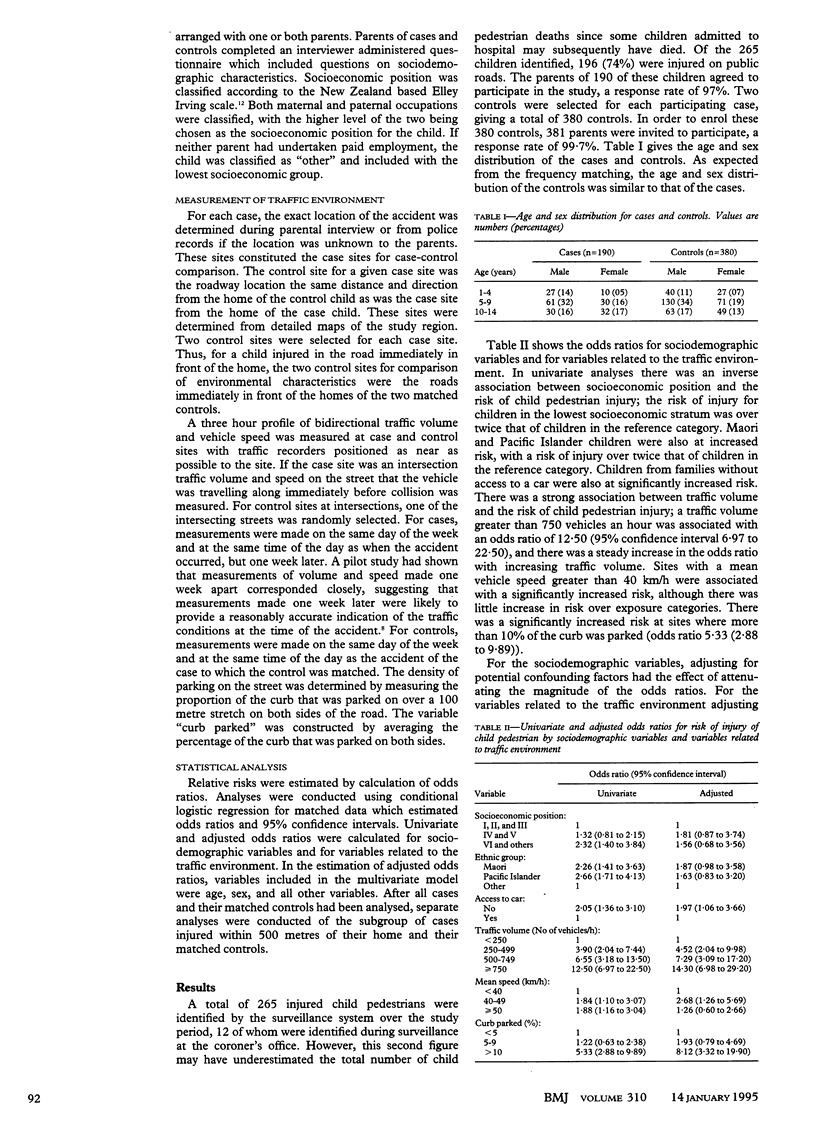

OBJECTIVE--To identify and assess contribution of environmental risk factors for injury of child pedestrians by motor vehicles. DESIGN--Community based case-control study. Environmental characteristics of sites of child pedestrian injury were compared with the environmental characteristics of selected comparison sites. Each comparison site was the same distance and direction from home of control child as was the injury site from home or relevant case child. Two control sites were selected for each injury site. SETTING--Auckland region of New Zealand. SUBJECTS--Cases were 190 child pedestrians aged < 15 who were killed or hospitalised after collision with a motor vehicle on a public road during two years and two months. Controls were 380 children randomly sampled from population and frequency matched for age and sex. MAIN OUTCOME MEASURE--Traffic volume and speed and level of parking on curbs at injury sites and comparison sites. RESULTS--Risk of injury of child pedestrians was strongly associated with traffic volume: risk of injury at sites with highest traffic volumes was 14 times greater than that at least busy sites (odds ratio 14.30; 95% confidence interval 6.98 to 29.20), and risk increased with increasing traffic volume. High density of curb parking was also associated with increased risk (odds ratio 8.12; 3.32 to 19.90). Risk was increased at sites with mean speeds over 40 km/h (odds ratio 2.68; 1.26 to 5.69), although risk did not increase further with increasing speed. CONCLUSION--Reducing traffic volume in urban areas could significantly reduce rates of child pedestrian injury. Restricting curb parking may also be effective.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Engel U., Thomsen L. K. Safety effects of speed reducing measures in Danish residential areas. Accid Anal Prev. 1992 Feb;24(1):17–28. doi: 10.1016/0001-4575(92)90068-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendrick D. Prevention of pedestrian accidents. Arch Dis Child. 1993 May;68(5):669–672. doi: 10.1136/adc.68.5.669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller B. A., Rivara F. P., Lii S. M., Weiss N. S. Environmental factors and the risk for childhood pedestrian-motor vehicle collision occurrence. Am J Epidemiol. 1990 Sep;132(3):550–560. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pless I. B., Verreault R., Arsenault L., Frappier J. Y., Stulginskas J. The epidemiology of road accidents in childhood. Am J Public Health. 1987 Mar;77(3):358–360. doi: 10.2105/ajph.77.3.358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivara F. P., Barber M. Demographic analysis of childhood pedestrian injuries. Pediatrics. 1985 Sep;76(3):375–381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivara F. P. Child pedestrian injuries in the United States. Current status of the problem, potential interventions, and future research needs. Am J Dis Child. 1990 Jun;144(6):692–696. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1990.02150300090023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts I. G. International trends in pedestrian injury mortality. Arch Dis Child. 1993 Feb;68(2):190–192. doi: 10.1136/adc.68.2.190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts I., Coggan C. Blaming children for child pedestrian injuries. Soc Sci Med. 1994 Mar;38(5):749–753. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)90465-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts I., Kolbe A., White J. Non-traffic child pedestrian injuries. J Paediatr Child Health. 1993 Jun;29(3):233–234. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.1993.tb00494.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts I., Lee-Joe T. Effect of exposure measurement error in a case-control study of child pedestrian injuries. Epidemiology. 1993 Sep;4(5):477–479. doi: 10.1097/00001648-199309000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts I., Marshall R., Norton R. Child pedestrian mortality and traffic volume in New Zealand. BMJ. 1992 Aug 1;305(6848):283–283. doi: 10.1136/bmj.305.6848.283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts I., Norton R., Dunn R., Hassall I., Lee-Joe T. Environmental factors and child pedestrian injuries. Aust J Public Health. 1994 Mar;18(1):43–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-6405.1994.tb00193.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts I., Norton R., Hassall I. Child pedestrian injury 1978-87. N Z Med J. 1992 Feb 26;105(928):51–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts I., Streat S., Judson J., Norton R. Critical injuries in paediatric pedestrians. N Z Med J. 1991 Jun 26;104(914):247–248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts I. Why have child pedestrian death rates fallen? BMJ. 1993 Jun 26;306(6894):1737–1739. doi: 10.1136/bmj.306.6894.1737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]