Abstract

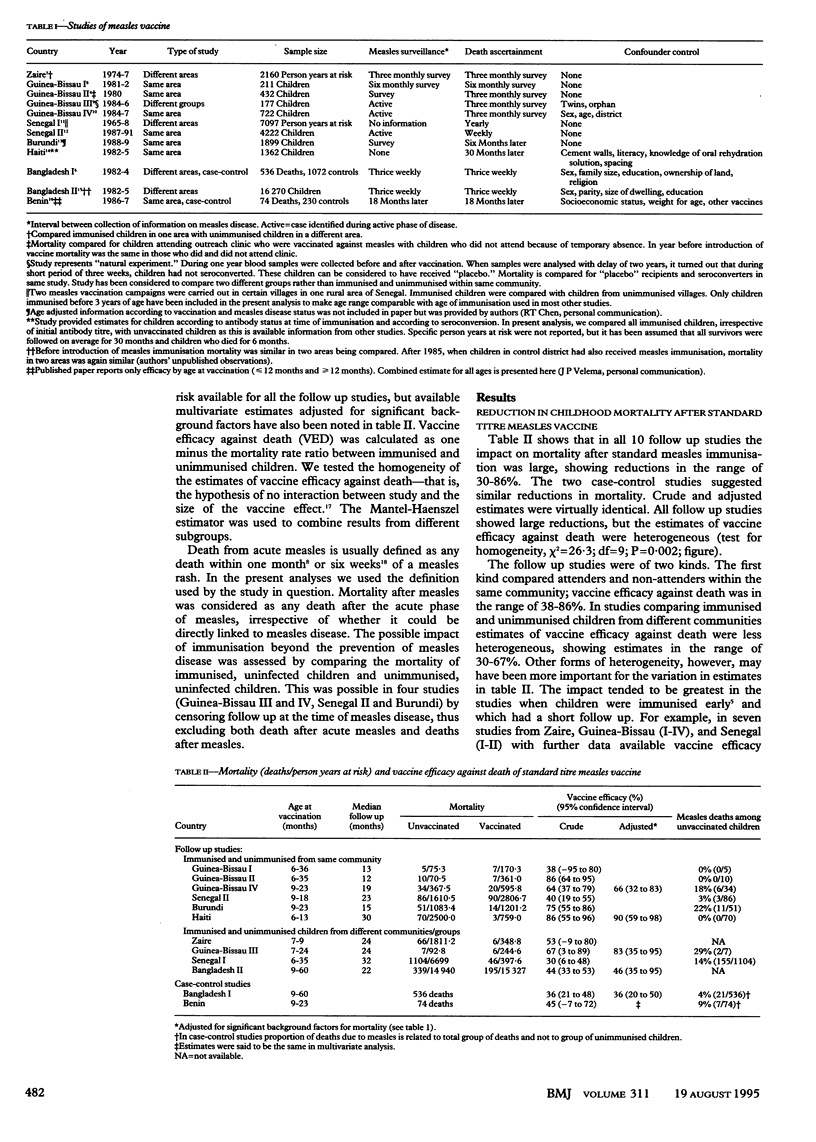

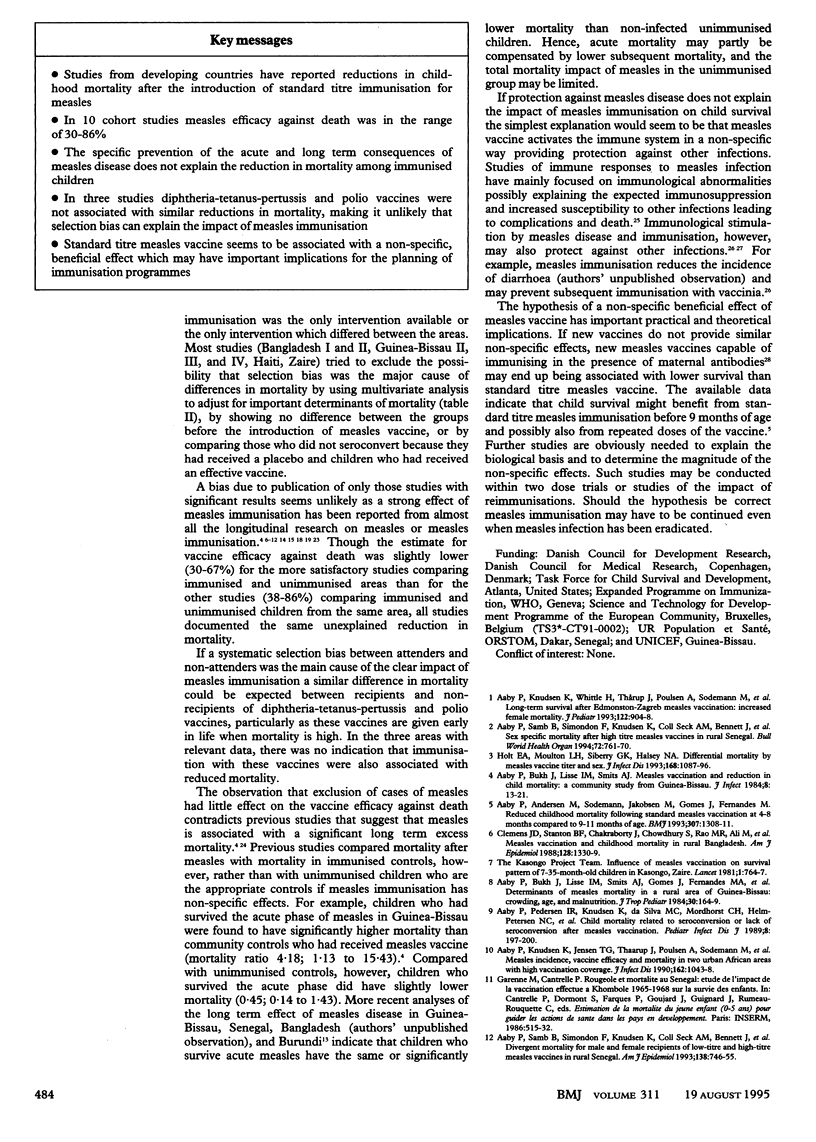

OBJECTIVE--To examine whether the reduction in mortality after standard titre measles immunisation in developing countries can be explained simply by the prevention of acute measles and its long term consequences. DESIGN--An analysis of all studies comparing mortality of unimmunised children and children immunised with standard titre measles vaccine in developing countries. STUDIES--10 cohort and two case-control studies from Bangladesh, Benin, Burundi, Guinea-Bissau, Haiti, Senegal, and Zaire. MAIN OUTCOME MEASURES--Protective efficacy of standard titre measles immunisation against all cause mortality. Extent to which difference in mortality between immunised and unimmunised children could be explained by prevention of measles disease. RESULTS--Protective efficacy against death after measles immunisation ranged from 30% to 86%. Efficacy was highest in the studies with short follow up and when children were immunised in infancy (range 44-100%). Vaccine efficacy against death was much greater than the proportion of deaths attributed to acute measles disease. In four studies from Guinea-Bissau, Senegal, and Burundi vaccine efficacy against death remained almost unchanged when cases of measles were excluded from the analysis. Diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis and polio vaccinations were not associated with reduction in mortality. CONCLUSION--These observations suggest that standard titre measles vaccine may confer a beneficial effect which is unrelated to the specific protection against measles disease.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Aaby P., Andersen M., Sodemann M., Jakobsen M., Gomes J., Fernandes M. Reduced childhood mortality after standard measles vaccination at 4-8 months compared with 9-11 months of age. BMJ. 1993 Nov 20;307(6915):1308–1311. doi: 10.1136/bmj.307.6915.1308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aaby P., Bukh J., Lisse I. M., Smits A. J., Gomes J., Fernandes M. A., Indi F., Soares M. Determinants of measles mortality in a rural area of Guinea-Bissau: crowding, age, and malnutrition. J Trop Pediatr. 1984 Jun;30(3):164–168. doi: 10.1093/tropej/30.3.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aaby P., Bukh J., Lisse I. M., Smits A. J. Measles vaccination and reduction in child mortality: a community study from Guinea-Bissau. J Infect. 1984 Jan;8(1):13–21. doi: 10.1016/s0163-4453(84)93192-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aaby P., Knudsen K., Jensen T. G., Thårup J., Poulsen A., Sodemann M., da Silva M. C., Whittle H. Measles incidence, vaccine efficacy, and mortality in two urban African areas with high vaccination coverage. J Infect Dis. 1990 Nov;162(5):1043–1048. doi: 10.1093/infdis/162.5.1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aaby P., Knudsen K., Whittle H., Lisse I. M., Thaarup J., Poulsen A., Sodemann M., Jakobsen M., Brink L., Gansted U. Long-term survival after Edmonston-Zagreb measles vaccination in Guinea-Bissau: increased female mortality rate. J Pediatr. 1993 Jun;122(6):904–908. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(09)90015-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aaby P., Pedersen I. R., Knudsen K., da Silva M. C., Mordhorst C. H., Helm-Petersen N. C., Hansen B. S., Thårup J., Poulsen A., Sodemann M. Child mortality related to seroconversion or lack of seroconversion after measles vaccination. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1989 Apr;8(4):197–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aaby P., Samb B., Simondon F., Knudsen K., Seck A. M., Bennett J., Markowitz L., Rhodes P., Whittle H. Sex-specific differences in mortality after high-titre measles immunization in rural Senegal. Bull World Health Organ. 1994;72(5):761–770. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aaby P., Samb B., Simondon F., Knudsen K., Seck A. M., Bennett J., Whittle H. Divergent mortality for male and female recipients of low-titer and high-titer measles vaccines in rural Senegal. Am J Epidemiol. 1993 Nov 1;138(9):746–755. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen R. T., Weierbach R., Bisoffi Z., Cutts F., Rhodes P., Ramaroson S., Ntembagara C., Bizimana F. A 'post-honeymoon period' measles outbreak in Muyinga sector, Burundi. Int J Epidemiol. 1994 Feb;23(1):185–193. doi: 10.1093/ije/23.1.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clemens J. D., Stanton B. F., Chakraborty J., Chowdhury S., Rao M. R., Ali M., Zimicki S., Wojtyniak B. Measles vaccination and childhood mortality in rural Bangladesh. Am J Epidemiol. 1988 Dec;128(6):1330–1339. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleiss J. L. The statistical basis of meta-analysis. Stat Methods Med Res. 1993;2(2):121–145. doi: 10.1177/096228029300200202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garenne M., Aaby P. Pattern of exposure and measles mortality in Senegal. J Infect Dis. 1990 Jun;161(6):1088–1094. doi: 10.1093/infdis/161.6.1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gellin B. G., Katz S. L. Measles: state of the art and future directions. J Infect Dis. 1994 Nov;170 (Suppl 1):S3–14. doi: 10.1093/infdis/170.supplement_1.s3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin D. E., Ward B. J., Esolen L. M. Pathogenesis of measles virus infection: an hypothesis for altered immune responses. J Infect Dis. 1994 Nov;170 (Suppl 1):S24–S31. doi: 10.1093/infdis/170.supplement_1.s24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HARTFIELD J., MORLEY D. Efficacy of measles vaccine. J Hyg (Lond) 1963 Mar;61:143–147. doi: 10.1017/s0022172400020817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt E. A., Boulos R., Halsey N. A., Boulos L. M., Boulos C. Childhood survival in Haiti: protective effect of measles vaccination. Pediatrics. 1990 Feb;85(2):188–194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt E. A., Moulton L. H., Siberry G. K., Halsey N. A. Differential mortality by measles vaccine titer and sex. J Infect Dis. 1993 Nov;168(5):1087–1096. doi: 10.1093/infdis/168.5.1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hull H. F., Williams P. J., Oldfield F. Measles mortality and vaccine efficacy in rural West Africa. Lancet. 1983 Apr 30;1(8331):972–975. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(83)92091-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenig M. A., Khan M. A., Wojtyniak B., Clemens J. D., Chakraborty J., Fauveau V., Phillips J. F., Akbar J., Barua U. S. Impact of measles vaccination on childhood mortality in rural Bangladesh. Bull World Health Organ. 1990;68(4):441–447. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rooth I., Sinani H. M., Smedman L., Björkman A. A study on malaria infection during the acute stage of measles infection. J Trop Med Hyg. 1991 Jun;94(3):195–198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velema J. P., Alihonou E. M., Gandaho T., Hounye F. H. Childhood mortality among users and non-users of primary health care in a rural west African community. Int J Epidemiol. 1991 Jun;20(2):474–479. doi: 10.1093/ije/20.2.474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]