Abstract

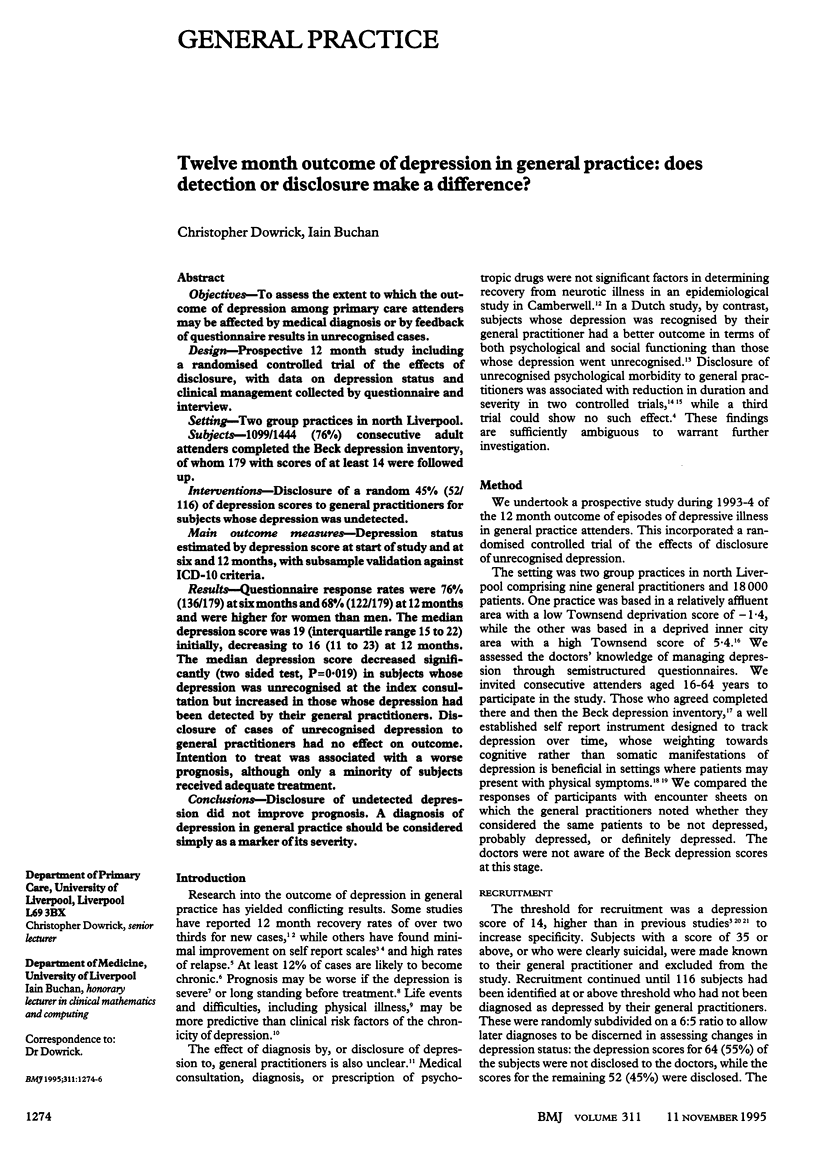

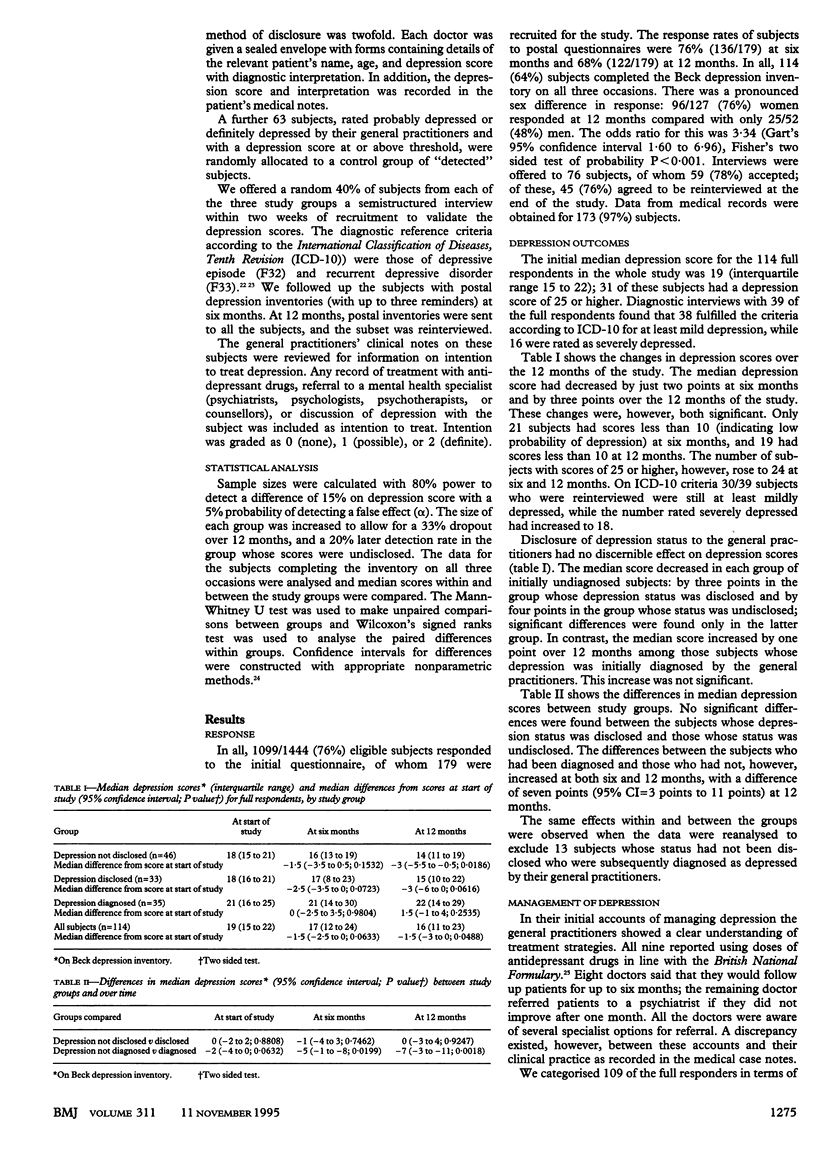

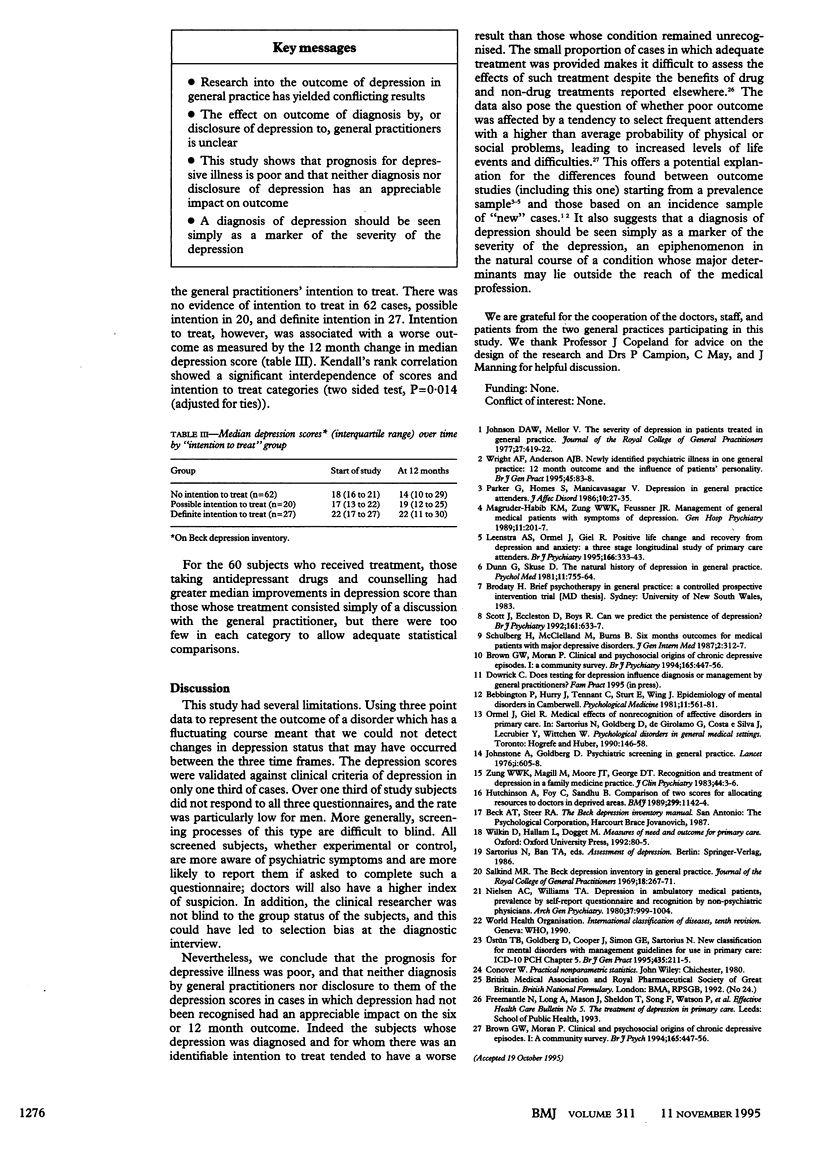

OBJECTIVES--To assess the extent to which the outcome of depression among primary care attenders may be affected by medical diagnosis or by feedback of questionnaire results in unrecognised cases. DESIGN--Prospective 12 month study including a randomised controlled trial of the effects of disclosure, with data on depression status and clinical management collected by questionnaire and interview. SETTING--Two group practices in north Liverpool. SUBJECTS--1099/1444 (76%) consecutive adult attenders completed the Beck depression inventory, of whom 179 with scores of at least 14 were followed up. INTERVENTIONS--Disclosure of a random 45% (52/116) of depression scores to general practitioners for subjects whose depression was undetected. MAIN OUTCOME MEASURES--Depression status estimated by depression score at start of study and at six and 12 months, with subsample validation against ICD-10 criteria. RESULTS--Questionnaire response rates were 76% (136/179) at six months and 68% (122/179) at 12 months and were higher for women than men. The median depression score was 19 (interquartile range 15 to 22) initially, decreasing to 16 (11 to 23) at 12 months. The median depression score decreased significantly (two sided test, P = 0.019) in subjects whose depression was unrecognised at the index consultation but increased in those whose depression had been detected by their general practitioners. Disclosure of cases of unrecognised depression to general practitioners had no effect on outcome. Intention to treat was associated with a worse prognosis, although only a minority of subjects received adequate treatment. CONCLUSIONS--Disclosure of undetected depression did not improve prognosis. A diagnosis of depression in general practice should be considered simply as a marker of its severity.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Bebbington P., Hurry J., Tennant C., Sturt E., Wing J. K. Epidemiology of mental disorders in Camberwell. Psychol Med. 1981 Aug;11(3):561–579. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700052879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown G. W., Moran P. Clinical and psychosocial origins of chronic depressive episodes. I: A community survey. Br J Psychiatry. 1994 Oct;165(4):447–456. doi: 10.1192/bjp.165.4.447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown G. W., Moran P. Clinical and psychosocial origins of chronic depressive episodes. I: A community survey. Br J Psychiatry. 1994 Oct;165(4):447–456. doi: 10.1192/bjp.165.4.447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn G., Skuse D. The natural history of depression in general practice: stochastic models. Psychol Med. 1981 Nov;11(4):755–764. doi: 10.1017/s003329170004126x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson D. A., Mellor V. The severity of depression in patients treated in general practice. J R Coll Gen Pract. 1977 Jul;27(180):419–422. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnstone A., Goldberg D. Psychiatric screening in general practice. A controlled trial. Lancet. 1976 Mar 20;1(7960):605–608. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(76)90415-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leenstra A. S., Ormel J., Giel R. Positive life change and recovery from depression and anxiety. A three-stage longitudinal study of primary care attenders. Br J Psychiatry. 1995 Mar;166(3):333–343. doi: 10.1192/bjp.166.3.333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magruder-Habib K., Zung W. W., Feussner J. R., Alling W. C., Saunders W. B., Stevens H. A. Management of general medical patients with symptoms of depression. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1989 May;11(3):201–221. doi: 10.1016/0163-8343(89)90042-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen A. C., 3rd, Williams T. A. Prevalence by Self-report questionnaire and recognition by nonpsychiatric physicians. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1980 Sep;37(9):999–1004. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1980.01780220037003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker G., Holmes S., Manicavasagar V. Depression in general practice attenders. "Caseness", natural history and predictors of outcome. J Affect Disord. 1986 Jan-Feb;10(1):27–35. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(86)90046-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulberg H. C., McClelland M., Gooding W. Six-month outcomes for medical patients with major depressive disorders. J Gen Intern Med. 1987 Sep-Oct;2(5):312–317. doi: 10.1007/BF02596165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott J., Eccleston D., Boys R. Can we predict the persistence of depression? Br J Psychiatry. 1992 Nov;161:633–637. doi: 10.1192/bjp.161.5.633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright A. F., Anderson A. J. Newly identified psychiatric illness in one general practice: 12-month outcome and the influence of patients' personality. Br J Gen Pract. 1995 Feb;45(391):83–87. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zung W. W., Magill M., Moore J. T., George D. T. Recognition and treatment of depression in a family medicine practice. J Clin Psychiatry. 1983 Jan;44(1):3–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]