Introduction

Approximately 108 tons per year of ammonia are formed in the environment from dinitrogen, an amount equivalent to that formed in the Haber-Bosch process (at 350–550 °C and 150–350 atm).1 It was first recognized in the 1960’s that fixation of dinitrogen in the environment is carried out in certain bacteria by a metalloenzyme, a FeMo nitrogenase.2–5 “Alternative” nitrogenases are now known, one that contains vanadium instead of molybdenum (which functions when Mo levels are low and V is available) and another that contains only iron (which functions when both Mo and V levels are low).6–8 The FeMo nitrogenase has been purified and studied for decades. It also has been crystallized and subjected to X-ray studies that have elicited a great deal of discussion concerning the mechanism of dinitrogen reduction.9–12 However, it is fair to say that in spite of a huge effort to understand how dinitrogen is reduced by various nitrogenases over a period of more than forty years, no definitive conclusions concerning the site and mechanism of dinitrogen reduction in nitrogenase(s) have been reached.13

Transition metal dinitrogen chemistry began in 1965 with the discovery of [Ru(NH3)5(N2)]2+, which was prepared by treating Ru salts with hydrazine.14 As more dinitrogen complexes were uncovered, it seemed possible that a transition metal complex might be able to catalyze the reduction of dinitrogen to ammonia under mild conditions in solution with protons and electrons, or the combination of dinitrogen with other elements in a selective manner under mild conditions.15–21 Hundreds of man years have been invested in these goals. Although dinitrogen at 1 atm combines readily with lithium at room temperature, the development of catalytic reactions under mild conditions that involve dinitrogen has been a formidable problem. Reduction of dinitrogen to ammonia in solution with protons and electrons carries with it the fact that protons are reduced readily to dihydrogen. Therefore reduction of one of the most stable molecules known in a true homogeneous nonenzymatic catalytic reaction with protons and electrons has been extraordinarily challenging.

The principles of reduction of dinitrogen to ammonia at a single metal center by Mo(0) and W(0) dinitrogen complexes were established in studies that began in the late 60’s, primarily by the groups directed by Chatt and Hidai. Over a period of years it was demonstrated that dinitrogen could be bound and reduced to ammonia through a series of approximately a dozen intermediates, the most important of them being M(N2), M-N=NH, M=N-NH2, M≡N, M=NH, M-NH2, and M(NH3) species. Although examples of virtually all of the proposed intermediates for reduction of dinitrogen at a single Mo or W center in a “Chatt cycle” were isolated, no catalytic reduction of dinitrogen to ammonia was ever achieved.

One reaction is known in which dinitrogen is reduced to a mixture of hydrazine and ammonia (~10:1).22 Molybdenum is required and dinitrogen reduction is catalytic with respect to molybdenum. The reaction is run in methanol in the presence of magnesium hydroxide and a strong reducing agent such as sodium amalgam. Few details concerning the mechanism of this reaction have been established and the possibility that hydrazine is the primary product apparently has not been eliminated.

In the last 10 years we have been exploring early transition metal complexes that contain a triamidoamine ligand ([(RNCH2CH2)3N]3−).23 Recently we were attracted to the chemistry of Mo complexes that contain the [HIPTN3N]3− ligand, where HIPT = 3,5-(2,4,6-i-Pr3C6H2)2C6H3 (HexaIsoPropylTerphenyl; see Figure 1).24,25 This ligand was designed to prevent formation of relatively stable and unreactive [ArN3N]Mo-N=N-Mo[ArN3N] complexes, maximize steric protection of a metal coordination site in a monometallic species, and provide increased solubility in nonpolar solvents. Eight of the proposed intermediates in a hypothetical “Chatt-like” reduction of dinitrogen (Figure 2) were prepared and characterized.24–27 These include paramagnetic Mo(N2) (1, Figure 1), diamagnetic [Mo(N2)]− (2), diamagnetic Mo-N=N-H (3), diamagnetic [Mo=N-NH2]BAr’4 (4; Ar’ = 3,5-(CF3)2C6H3), diamagnetic Mo≡N (7), diamagnetic [Mo=NH]BAr’4 (8), paramagnetic [Mo(NH3)]BAr’4 (12), and paramagnetic Mo(NH3) (13). With the exception of 7 all are extremely sensitive to oxygen. Several of these species then were employed successfully to reduce dinitrogen catalytically to ammonia with protons and electrons26 and we have been able to study several steps in the catalytic cycle. Although much remains to be done, we now know something about how this remarkable reaction proceeds. The purpose of this Account is to summarize the major findings in this area since the [HIPTN3N]Mo species were first reported.24

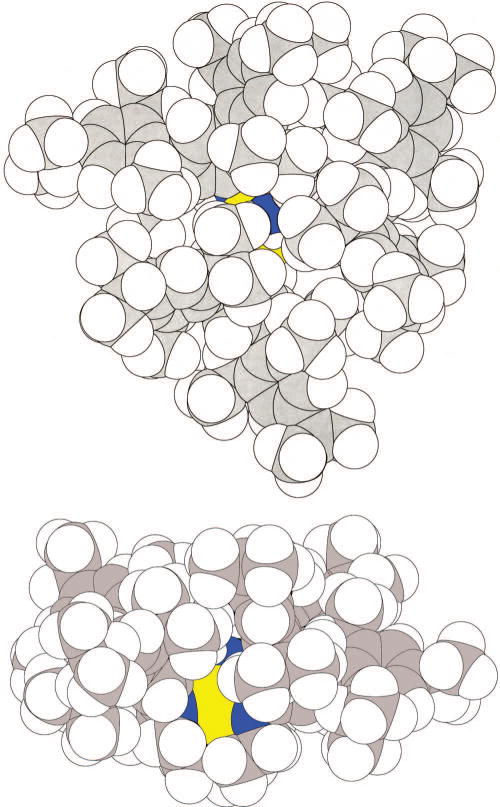

Figure 1.

A drawing of [HIPTN3N]Mo(N2) = Mo(N2).

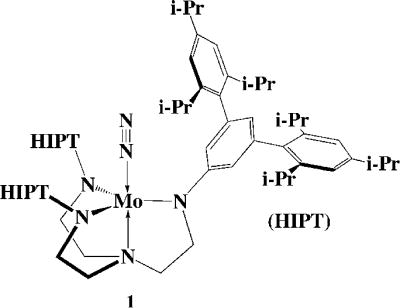

Figure 2.

Proposed intermediates in the reduction of dinitrogen at a [HIPTN3N]Mo (Mo) center through the step-wise addition of protons and electrons.

Some structural characteristics of [HIPTN3N]Mo complexes

Trigonal bipyramidal molybdenum complexes that contain the [HIPTN3N]3− ligand all contain an approximately trigonal pocket in which N2 or its partially or wholly reduced products are protected to a dramatic degree by three HIPT groups clustered around it. An example is the structure of Mo(NH3) shown in Figure 3. The basic characteristics of binding of the three amides and the amine in [HIPTN3N]Mo complexes do not vary dramatically from complex to complex. As a consequence of relatively free rotation of the HIPT substituents about the N-Cipso bond they adopt a wide variety of orientations in response to what are usually subtle, but sometimes not so subtle, steric demands of the ligand or ligands bound in the trigonal pocket. A dramatic example of the degree to which the HIPT substituents can respond to the steric demands imposed by a ligand bound in the trigonal pocket is [Mo(2,6-dimethylpyridine)]+ (Equation 1).27 The 2,6-lutidine is bound “off-axis” to a significant degree (Namine-Mo-Nlut = 157°) in a “slot” created by two of the HIPT groups. Since no asymmetry is present on the NMR time scale at room temperature in solution, the HIPT groups, as well as the ligand or ligands in the trigonal pocket, must be rotating and rearranging at a rate near or faster than the NMR time scale.

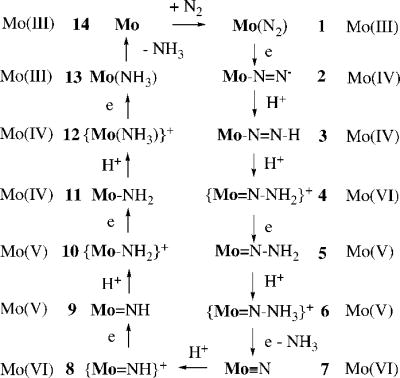

Figure 3.

Two space filling views of the structure of [HIPTN3N](NH3) from the top (above) and from the side (below; Mo is yellow; N is dark blue).

|

(1) |

The orbital to which the lutidine is bound in [Mo(2,6-dimethylpyridine)]+ can be described as a sigma-type hybrid formed from the “dz2”, dxz, and dyz orbitals, with the three-fold axis being the z axis. In general, these three orbitals can be employed to form 3σ,1π and 2σ,or 2π and 1σ bonds to a ligand or ligands bound in the trigonal pocket.23 Six-coordinate species are known in TMS or C6F5 triamidoamine Mo complexes when strongly binding ligands are present (CO or isonitriles),28 although six-coordinate species have not yet been observed in [HIPTN3N]MoLx systems that do not contain CO or RNC ligands.

The catalytic reduction of dinitrogen

Dinitrogen is reduced catalytically in heptane with [2,6-lutidinium]BAr’4 (Ar’ = 3,5-(CF3)2C6H3) as the proton source and decamethylchromocene as the electron source in the presence of several of the isolated complexes shown in Figure 2.26 We chose 2,6-lutidinium because it is a relatively weak acid (pKa in water = 6.75) and because we felt that the 2,6-lutidine that is formed after delivery of the proton is unlikely to bind strongly to a neutral (Mo(III)) center. The BAr’4− anion was chosen because it is large, unlikely to interact with the metal in {[HIPTN3N]Mo}+ complexes, and likely to lead to salts that are soluble in relatively nonpolar solvents. Decamethylchromocene was chosen as the electron source because it was found to reduce [Mo(NH3)]BAr’4 to Mo(NH3) in benzene. (E° for Mo(NH3)+/0 = −1.51 V relative to FeCp2+/0 while E° for CrCp*20/+ = − 1.47 V in THF.27) However, CrCp*2 cannot fully reduce Mo(N2) to [Mo(N2)]− (E° for [Mo(N2)]0/− is −1.81V in THF vs. FeCp2+/0).27 Heptane was chosen as the solvent in order to minimize the solubility of [2,6-lutidinium]BAr’4 and thereby minimize direct reduction of protons by CrCp*2 in solution. Slow addition of the reducing agent in heptane to an Mo complex and [2,6-lutidinium]BAr’4 in heptane (over a period of 6 h with a syringe pump) was chosen in order to minimize exposure of protons to CrCp*2 at high concentration.

A growing number of catalytic runs by several researchers with several different Mo derivatives (usually 1, 3, 7, or 12) reveal that a total of 7–8 equivalents of ammonia are formed out of ~12 possible (depending upon the Mo derivative employed), which suggests an efficiency of ~65% based on the reducing equivalents available. (The efficiency of formation of ammonia from the gaseous dinitrogen present is 55–60%.) A run employing Mo-15N=15NH under 15N2 yielded entirely 15N-labeled ammonia. We now know that no hydrazine is formed,29 but still have not established that any reducing agent that is not consumed in making ammonia is consumed to form dihydrogen. It is clear, however, that [2,6-lutidinium]BAr’4 does react rapidly with CrCp*2 in benzene to yield [CrCp*2]BAr’4 and dihydrogen. CoCp2, which is a weaker reducing agent than CrCp*2 (the CoCp20/+ couple is −1.33 V vs. FeCp2+/0 in either THF or PhF), also can be employed as the reducing agent for catalytic dinitrogen reduction, although it is approximately half as efficient as CrCp*2.27

The parent diazenido complex, Mo-N=NH

Mo-N=NH (3 in Figure 2) has been prepared by protonation of Mo-N=N− with [Et3NH]BAr’4, and has been characterized structurally.25,27 Although the proton on the β nitrogen atom could not be located in the X-ray study, 15N and proton NMR studies have established conclusively that a proton is present on Nβ. Although there are many well-characterized examples in the literature of M-N=NR complexes where R ≠ H, parent diazenido (M-N=NH) complexes are extremely rare.30,31 To our knowledge no other terminal M-N=NH species has been characterized structurally or via NMR studies of 15N-labeled samples, with the exception of the W analog of Mo-N=NH (see later). Upon heating in benzene, Mo-N=NH slowly decomposes to MoH and dinitrogen in a first order process (k = 2.2 × 10−6 s−1, t1/2 = 90 h at 61°C).25 Decomposition of Mo-N=NH is accelerated an order of magnitude in the presence of 1% [Et3NH][OTf] or [Et3NH]BAr’4; mechanistic details, and whether the rate of decomposition is further accelerated in the presence of additional [Et3NH]BAr’4 or [2,6-LutH]BAr’4, are not yet available. Decomposition of Mo-N=NH is a problem even at room temperature over the long term, a circumstance that complicated obtaining crystals suitable for an X-ray study.27 In the presence of [H(Et2O)2]BAr’4 Mo-N=NH is protonated at Nβ to yield [Mo=NNH2]+, but [2,6-LutH]BAr’4 only partially and reversibly protonates Mo-N=NH.

It has been established that Mo-N=NH is formed rapidly upon treatment of Mo(N2) with CoCp2 and [2,6-lutidinium]BAr’4 in benzene, even though neither reacts alone with Mo(N2). CoCp2 is too weak a reducing agent to reduce Mo(N2) fully to [Mo-N=N]−, but it is difficult to exclude the possibility that Mo-N=NH is formed through a rapid and reversible reduction of Mo(N2) to give a minute amount of [Mo-N=N]− in equilibrium with Mo(N2), followed by a rapid protonation of [Mo-N=N]−. Interestingly, addition of [2,6-lutidinium]BAr’4 to Mo(N2) has been shown to yield (reversibly) ~30% of a species in fluorobenzene in which νNN has increased from 1990 cm−1 to 2056 cm−1, consistent with protonation of Mo(N2) to yield a cationic species. However dinitrogen cannot be the site of protonation. Two possibilities are the metal center, or an amido nitrogen. In any cationic species the potential for addition of an electron should be shifted considerably in the positive direction by as much as 500 or 600 mV.32 In short, the reductive protonation of Mo(N2) to Mo-N=NH could be proton catalyzed.

The role of MoH

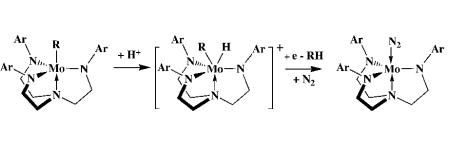

The hydride MoH is most readily prepared by treating [Mo(NH3)]BPh4 with LiBHEt3.27 As mentioned above, it is also the product of decomposition of Mo-N=NH. MoH may be formed under catalytic conditions, although that has not yet been established.

It turns out that MoH is as efficient a catalyst precursor in dinitrogen reduction as any species we have employed. One can readily imagine how this might happen, as shown in equation 2. In short, MoH is a hydrogenase. However, the rate of formation of dihydrogen in

|

(2) |

the manner shown in equation 2, versus the rates of all other reactions in which dihydrogen may be formed under catalytic conditions, including “direct” reduction by electron transfer, is not yet known. It should be noted that formation of one equivalent of dihydrogen when the FeMo nitrogenase reduces dinitrogen has been proposed to be an integral aspect of the reduction process itself, i.e., not a competitive product that may or may not be formed at the same site at which dinitrogen is reduced. More than one dihydrogen is formed per dinitrogen reduced in alternative nitrogenase systems.

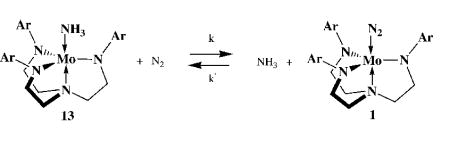

The formation of Mo(NH3) and its conversion to Mo(N2)

It has been established that [Mo(NH3)]BAr’4 is formed upon treatment of Mo(N2) in benzene with sufficient CoCp2 and [2,6-lutidinium]BAr’4 and that a stronger reducing agent such as CrCp*2 will reduce [Mo(NH3)]BAr’4 to Mo(NH3) in benzene. A catalytic cycle is then “completed” when Mo(NH3) (13) is converted into Mo(N2) (1, equation 3). The equilibrium constant for conversion of Mo(NH3) in the presence of dinitrogen into a mixture of Mo(N2),

|

(3) |

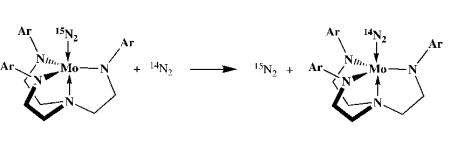

Mo(NH3), and ammonia has been measured in C6D6 at 50°C and found to be 1.2.27 It also has been shown that an equilibrium (Keq 0.1) between Mo(NH3), dinitrogen, Mo(N2), and ammonia is established in 1–2 h under an atmosphere of ammonia (0.28 atm, ~21 equiv vs. Mo) and dinitrogen.29 A reaction in which Mo(15N2) is converted into Mo(14N2) under 1 atm of 14N2 (a large excess vs. Mo; equation 4) has a half-life of ~35 h at 15 psi (1 atm),25 32 h at 30 psi,33 and

|

(4) |

30 h at 55 psi,33 which suggests that the exchange of 15N2 for 14N2 is independent of dinitrogen pressure. Therefore dinitrogen exchange (equation 4) is dissociative with the “naked” species (14, Figure 2) the likely intermediate. Since the equilibrium in equation 3 is established in only 1–2 h, conversion of 1 to 13 (and by definition, 13 to 1) does not involve 14 as an intermediate. All data in hand so far (see below) suggest that this is the case.

The rate of conversion of Mo(NH3) into Mo(N2) under dinitrogen in the absence of [2,6-lutidinium]BAr’4 has been studied in a preliminary and semi-quantitative fashion by IR spectroscopy and Differential Pulse Voltammetry.29,33 The conversion of Mo(NH3) into Mo(N2) in the absence of added ammonia is not a simple reaction, since the ammonia that is formed in solution not only back reacts with Mo(N2) to give Mo(NH3), but also begins to enter the head space above solvents such as benzene or heptane. (Preliminary measurements suggest that in C6D6 at 22 °C approximately the same amount of ammonia is present in a given volume of C6D6 as in three times that volume of head space at equilibrium.) In heptane the conversion of Mo(NH3) into Mo(N2) follows what is close to first order kinetics in Mo with a half-life for the conversion at 22°C and 1 atm of ~115 min. (The plot of ln(1 − Mo/Mo∞) vs. time is slightly curved, as a consequence of the back reaction between ammonia in solution and Mo(N2) to reform Mo(NH3), so these measured rates of conversion are semi-quantitative.) At 2 atm the half-life is ~45 min, which suggests that the conversion depends on the concentration of dinitrogen to the first power.29,33 Conversion of Mo(NH3) into Mo(N2) is dramatically accelerated at 1 atm in the presence of 4 equivalents of BPh3 (t1/2 is ~35 min), and the ln(1 − Mo/Mo∞) plot is strictly linear, most likely because BPh3 removes much or all of the ammonia formed in solution relatively efficiently.29,33 Much remains to be done to confirm that the interconversions of Mo(NH3) and Mo(N2) (equation 3), unlike interconversion of Mo(15N2) and Mo(14N2) (equation 4), are SN2 reactions. Therefore an inescapable consequence is that ammonia formed through reduction of dinitrogen will be an inhibitor of further dinitrogen reduction through displacement of the equilibrium shown in equation 3 to the left.

Variations of standard conditions

Preliminary results suggest that the amount of ammonia formed from dinitrogen at 2 atm under standard conditions is ~25% greater than at 1 atm, as one would expect on the basis of the nitrogen pressure dependence of the reaction shown in equation 3. If the reducing agent is added over a period of <1 min, then the amount of dinitrogen that is converted into ammonia is <10%; presumably electrons are consumed primarily to form dihydrogen. Since conversion of Mo(NH3) into Mo(N2) depends upon pressure, proton reduction in theory could be minimized at high dinitrogen pressures. An interesting question is whether the efficiency of conversion of dinitrogen into ammonia can be pushed beyond 75% (one equivalent of dihydrogen per dinitrogen reduced, as found in FeMo nitrogenase) under some conditions, e.g., at several atmospheres N2 pressure.

Dinitrogen reduction is inhibited by 2,6-lutidine, which is formed after lutidinium delivers a proton. For example, the amount of ammonia formed from dinitrogen decreases from 3.4 in a run employing 18 equiv of reducing agent to 0.5 in a run in which 145 equivalents of 2,6-lutidine had been added.29 There are several possible explanations for this effect, among them the possibility that excess 2,6-lutidine simply makes 2,6-lutidinium a poorer acid.

Not all [pyridinium]BAr’4 acids work well. No ammonia is formed from dinitrogen if 2,6-diphenylpyridinium or 3,5-dimethylpyridinium BAr’4 sources are employed, while 4.1 equivalents are formed from dinitrogen when [2,4-dimethylpyridinium]BAr’4 is employed under standard conditions (36 equiv of reducing agent) and 2.7 equivalents are formed when [2,6-diethylpyridinium]BAr’4 is employed.29 Not only must the solubility of the acid source, it’s pKa (in water), and the ability of the conjugate base to bind to Mo be considered in explaining these results, but also the bulk of the acid source as an ion pair. Two or more of these factors change when the acid source is changed, so it has been challenging to pinpoint the origin of any [pyridinium]+ effect.

Alternatives to the [HIPTN3N]3− ligand

Three “symmetric” variations of the [HIPTN3N]3− ligand have been explored.34 One is a hexa-t-butylterphenyl-substituted ([HTBTN3N]3−) ligand, a second is a hexamethylterphenyl-substituted ([HMTN3N]3−) ligand, and a third is a [pBrHIPTN3N]3− ligand, which is a [HIPTN3N]3− ligand in which the para position of the central phenyl ring is substituted with a bromide. IR and electrochemical studies suggest that complexes that contain the [HTBTN3N]3−ligand are slightly more electron rich than those that contain the parent [HIPTN3N]3− ligand, while those that contain the [pBrHIPTN3N]3− ligand are slightly more electron poor. One would expect [HTBTN3N]Mo complexes to be significantly more crowded sterically than [HIPTN3N]Mo complexes (an X-ray study of [HTBTN3N]MoCl shows this to be the case), [HMTN3N]Mo complexes to be significantly less crowded than [HIPTN3N]Mo complexes, and [pBrHIPTN3N]Mo complexes to have approximately the same steric crowding as [HIPTN3N]Mo complexes. In practice, transformations of [HTBTN3N]3− derivatives that involve electron and proton transfer (e.g., conversion of [HTBTN3N]Mo(N2) into [HTBTN3N]Mo-N=NH) are slower by perhaps an order of magnitude compared to analogous conversions of [HIPTN3N]3−derivatives, consistent with a high degree of steric crowding in [HTBTN3N]3− derivatives.

[pBrHIPTN3N]Mo≡N was found to be a catalyst for the formation of ammonia in yields only slightly less than those observed employing [HIPTN3N]3− derivatives (~65%). Generation of [pBrHIPTN3N]Mo(NH3) and observation of its conversion to [pBrHIPTN3N]Mo(N2) under 1 atm of dinitrogen in heptane at 22 °C showed that the half-life for formation of [pBrHIPTN3N]Mo(N2) is ~2 h, the same as for conversion of [HIPTN3N]Mo(NH3) into [HIPTN3N]Mo(N2).

[HTBTN3N]Mo≡N was found to be a poor catalyst for the reduction of dinitrogen, with only 1.06 equivalents of ammonia being observed. Therefore only 0.06 equivalents are formed from gaseous dinitrogen. One measurement of the rate of conversion of [HTBTN3N]Mo(NH3) into [HTBTN3N]Mo(N2) under conditions analogous to those employed for Mo(NH3) reveals that the “half-life” for conversion is approximately 30 hours instead of 2 hours, as it is for conversion of Mo(NH3) to Mo(N2).29 The observable (slower) coupled reduction of {[HTBTN3N]Mo(NH3)}+ to [HTBTN3N]Mo(NH3) and (slower) conversion of [HTBTN3N]Mo(NH3) to [HTBTN3N]Mo(N2) apparently cannot compete with formation of dihydrogen via “direct” reduction of protons.

Use of [HMTN3N]Mo≡N as a catalyst under standard conditions was also relatively unsuccessful; only 0.47 equivalents of ammonia were formed from dinitrogen. Low solubility of [HMTN3N]Mo≡N, and probably other intermediates (in heptane) is one possible problem. However, studies of other “hybrid” alternatives to the [HTBTN3N]3− ligand (vide infra) suggest that there may also be other problems.

Changing three substituents on the ligand at once is a relatively drastic variation. Therefore we were pleased to find that we could change the substituent on only one of the arms, i.e., we could prepare “hybrid” ligands of the type [(HIPTNCH2CH2)2NCH2CH2NAr]3−, where Ar is 3,5-dimethylphenyl, 3,5-dimethoxyphenyl, or 3,5-bistrifluoromethylphenyl (Figure 4).29 When [(HIPTNCH2CH2)2NCH2CH2NAr]Mo≡N species are employed in a standard attempted catalytic reaction, no ammonia is produced from dinitrogen using any of the three Ar variations. The half-life for conversion of [(HIPTNCH2CH2)2NCH2CH2NAr]Mo(NH3) into [(HIPTNCH2CH2)2NCH2CH2NAr]Mo(N2) was shown to be ~170 min when Ar = 3,5-(CF3)2C6H3 and < 30 min when Ar = 3,5-(OMe)2C6H3.29 Since the half-life for conversion of Mo(NH3) into Mo(N2) is ~120 min, reduction must fail in the “hybrid” cases for some reason other than a slow conversion of [hybrid]Mo(NH3) into [hybrid]Mo(N2).

Figure 4.

A drawing of a [hybrid]Mo(N2) complex.

The reason why [hybrid]Mo catalysts will not reduce dinitrogen is (we propose) a “shunt” in the catalytic cycle that consumes protons and electrons to yield hydrogen relatively rapidly. Since the three Ar groups are similar sterically, we suspect that the reaction that produces hydrogen is simply accelerated in the less crowded circumstance. Of the several possibilities at this stage, perhaps the simplest is hydrogen formation at the metal center, i.e., hydrogenase activity. In any case it is extraordinary that dinitrogen reduction fails when only one out of the three amido nitrogen substituents is a slightly smaller 3,5-disubstituted phenyl than a HIPT group.

Other metals

Many tungsten analogs of the species shown in Figure 2 have been synthesized and several have been structurally characterized, among them WN=NK, W(N2), [W(N2)]−, WN=NH, [W=NNH2]BAr’4, W≡N, and [W(NH3)]BAr’4.35 The structural, spectroscopic, and electrochemical trends are those one might expect. For example, νNN for W(N2) is found at 1888 cm−1 compared to 1990 cm−1 for Mo(N2), consistent with W(III) being a more powerful reductant of dinitrogen through π back donation. However, attempted catalytic reduction of dinitrogen using W(N2) as the catalyst under conditions identical or similar to those employed for catalytic reduction of dinitrogen by Mo(N2) and related Mo complexes yielded less than 2 equivalents of ammonia, i.e., only the dinitrogen initially bound to tungsten is reduced (partially) to ammonia; no atmospheric dinitrogen is reduced. At most 1.51 equivalents of ammonia were produced with CoCp*2 as the reductant and [2,6-LutH]BAr’4 as the acid.

One compound that is conspicuously absent in the list of isolated or observed complexes above is W(NH3). All efforts so far to observe this compound, or to observe W(N2) as a product of reduction of [W(NH3)]BAr’4 under dinitrogen, have failed. Therefore we suspect that one of the reasons why turnover is not a7chieved is the failure to generate W(NH3) and exchange ammonia for dinitrogen to yield W(N2). At present we could only speculate why this is the case. Another problem is that it is more difficult to reduce tungsten analogs of molybdenum compounds. For example, the reduction of W(N2) to [W(N2)]− is reversible at −2.27 V vs. FeCp2+/0 in 0.1M [Bu4N]BAr’4/PhF electrolyte, which is 0.46 V more negative than the Mo(N2)0/−potential under the same conditions. Taken together, and given the already extremely finely balanced nature of the Mo-catalyzed reduction of dinitrogen, it is perhaps not surprising that dinitrogen reduction fails using W(N2) under conditions where reduction using Mo(N2) is successful. It is interesting to note that a tungsten-substituted nitrogenase can be isolated from R. capsulatus, and that it is inactive for reduction of acetylene and dinitrogen, although it is relatively active for reduction of protons.36

Since TMS-substituted or C6F5-substituted triamidoamine complexes that contain vanadium are known,37,38 we were not surprised to find that [HIPTN3N]V(THF) can be prepared readily.39 An attempt to reduce dinitrogen under the standard set of conditions that have been successful for Mo compounds produced only traces of ammonia when [HIPTN3N]V(THF) was employed. It should be noted that the charges on any complex would be off by one, e.g., if the V(V) nitride were formed, it would have to be an anion. Ideally, therefore, a dianionic ligand might be more desirable, e.g., one which one of the anionic amido “arms” is instead a neutral donor. However, the “donor arm” in ligands of that type that we have prepared so far appears to dissociate and allow bimetallic species to form.39 Therefore this problem is unsolved.

Organometallic chemistry

As one might expect on the basis of work with other types of triamidoamine Mo complexes,23,28,40,41 it is possible to prepare organometallic derivatives such as Mo(η2-C2H4), Mo(η2-C2H2), Mo(CO), Mo(CN), Mo(CH2R) (R = methyl, pentyl, or heptyl), Mo(η2-CHCH2), Mo≡CR, [Mo(C2H4)]+, and [Mo(C2H2)]+.42 So far we know that Mo(η2-C2H4), Mo(η2-C2H2), Mo(hexyl), and Mo≡CH all yield ammonia when employed under standard conditions as “precatalysts” for the reduction of dinitrogen.43 The most successful is Mo(hexyl), which yields 6.3 equivalents of ammonia from dinitrogen (53%; cf. 7.7 equiv from dinitrogen, 64%, with MoH as the precursor). One can imagine that Mo(hexyl) is protonated to yield hexane and Mo(N2) in the presence of reducing agent and dinitrogen (equation 5). We have not yet

|

(5) |

attempted to reduce acetylene, a classic nitrogenase substrate, under the conditions that we have employed to reduce dinitrogen.

Mo(III) versus Mo(IV)+, ligand preferences, and the nature of [HIPTN3N]Mo

So far we have isolated [Mo(L)]+ species in which L is ammonia, 2,6-lutidine, pyridine, diethyl ether, and THF. We know that chemical reduction of [Mo(2,6-Lut)]+ with CrCp*2 under dinitrogen in C6D6 yields Mo(N2) immediately, while CV studies suggest that reduction of [Mo(THF)]+ yields Mo(N2) in less than 2 seconds.33 However, reduction of [Mo(NH3)]+ yields Mo(NH3), probably since ammonia is the strongest Brønsted base and the smallest of the σ donors in the list above. Therefore one might expect the rate of displacement of ammonia by dinitrogen to be the slowest.

The “naked” species, Mo, appears to be an intermediate in the SN1 conversion of 14N2 into Mo(15N2), but so far Mo has not been implicated in any other reaction, and all efforts to observe it have failed so far. In contrast, high spin Mo[N(t-Bu)Ar]3 (Ar = 3,5-Me2C6H3) has been prepared and studied by Cummins.44 Mo[N(t-Bu)Ar]3 reacts with dinitrogen to yield a [N(t-Bu)Ar]3Mo(μ-N2)Mo[N(t-Bu)Ar]3 species that then dissociates to yield two equivalents of [N(t-Bu)Ar]3Mo≡N. Addition of a donor to a trisamido species, which is analogous to the circumstance in four-coordinate Mo, would likely raise the energy of the dz2 orbital above dxz and dyz and might be expected to lead to a relatively reactive ground state low spin species that is poised to react with dinitrogen efficiently.

Recent calculations have established a detailed energy profile for the proposed steps in the Mo-catalyzed reduction of dinitrogen.45 Interestingly, a free energy input of ~190 kcal mol−1 is calculated to be involved in the conversion of dinitrogen to two equivalents of ammonia, which is the same as that obtained empirically for biological nitrogen fixation.

Summary

As far as we are aware, the [HIPTN3N]Mo system and some of its variations are the only nonenzymatic systems that will reduce dinitrogen catalytically and selectively to ammonia in the presence of protons and electrons at room temperature and pressure. We now can be relatively certain that reduction is accomplished at a single Mo center in a manner that so far appears to be analogous (approximately) to that proposed by Chatt and his group, with an important difference being that the highest possible oxidation states are involved (Mo(III) to Mo(VI)) in the cycle. Conversion of Mo(NH3) to Mo(N2) appears to be one of the slow steps in the successful reductions, in part because ammonia is an inhibitor. Although the catalytic system we have developed does not involve biologically relevant ligands, reduction of dinitrogen to ammonia in such a simple “artificial” Mo system suggests that Mo is exceptional, as Chatt suspected, in its ability to reduce dinitrogen, although it probably is not unique. Whether dinitrogen is reduced at molybdenum in FeMo nitrogenase is still speculative, although it is attractive to propose that it is. It is possible that dinitrogen is reduced at V or Fe when they substitute for Mo. It may prove to be considerably more difficult to design non-enzymatic V or Fe systems that reduce dinitrogen catalytically under conditions similar to those used in the [HIPTN3N]Mo reactions, primarily because V and Fe are less efficient than Mo. One also cannot state that dinitrogen must be reduced at low temperature and pressure only in the manner found in [HIPTN3N]Mo systems. However, at the same time one should ponder whether the sheer complexity of catalytic dinitrogen reduction to ammonia with protons and electrons automatically severely limits mechanistic alternatives under mild conditions. Finally, it is also interesting to speculate what other “high oxidation state” chemistry and what other catalytic reactions can be developed with complexes that contain the [HIPTN3N]3− ligand system.

Acknowledgments

R.R.S. is grateful to the National Institutes of Health (GM 31978) for research support.

References

- 1.Smil V. Enriching the Earth: Fritz Haber, Carl Bosch, and the transformation of world food production. MIT Press; Cambridge, Massachusetts: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burgess BK, Lowe DJ. Mechanism of molybdenum nitrogenase. Chem Rev. 1996;96:2983. doi: 10.1021/cr950055x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hardy RWF, Bottomley F, Burns RC. A Treatise on Dinitrogen Fixation. Wiley-Interscience; New York: 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Veeger C, Newton WE. Advances in Nitrogen Fixation Research. Dr. W. Junk/Martinus Nijhoff; Boston: 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coughlan MP, editor. Molybdenum and Molybdenum-containing Enzymes. Pergamon; New York: 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eady RR. Structure-Function Relationships of Alternative Nitrogenases. Chem Rev. 1996;96:3013. doi: 10.1021/cr950057h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith BE. Structure, function, and biosynthesis of the metallosulfur clusters in nitrogenases. Adv Inorg Chem. 1999;47:159. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rehder D. The coordination chemistry of vanadium as related to its biological functions. Coord Chem Rev. 1999;182:297. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Einsle O, Tezcan FA, Andrade SLA, Schmid B, Yoshida M, Howard JB, Rees DC. Nitrogenase MoFe-protein at 1.16 angstrom resolution: A central ligand in the FeMo-cofactor. Science. 2002;297:1696. doi: 10.1126/science.1073877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rees DC, Howard JB. Nitrogenase: standing at the crossroads. Curr Opinion Chem Biol. 2000;4:559. doi: 10.1016/s1367-5931(00)00132-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bolin JT, Ronco AE, Morgan TV, Mortenson LE, Xuong LE. The Unusual Metal-Clusters of Nitrogenase - Structural Features Revealed by X-Ray Anomalous Diffraction Studies of the MoFe Protein from Clostridium-Pasteurianum. Proc Nat Acad Sci. 1993;90:1078. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.3.1078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim J, Rees DC. Structure of FeMoco. Science. 1992;257:1677. doi: 10.1126/science.1529354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Seefeldt LC, Dance IG, Dean DR. Substrate Interactions with Nitrogenase: Fe versus Mo. Biochemistry. 2004;43:1401. doi: 10.1021/bi036038g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Allen AD, Senoff CV. Nitrogenopentammineruthenium(II) Complexes. J Chem Soc, Chem Commun. 1965:621. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chatt J, Dilworth JR, Richards RL. Recent Advances in the Chemistry of Nitrogen-Fixation. Chem Rev. 1978;78:589. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hidai M. Chemical nitrogen fixation by molybdenum and tungsten complexes. Coord Chem Rev. 1999:185–186. 99. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fryzuk MD, Johnson SA. The Continuing Story of Dinitrogen Activation. Coord Chem Rev. 2000:200–202. 379. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barriere F. Modeling of the molybdenum center in the nitrogenase FeMo cofactor. Coord Chem Rev. 2003;236:71. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Henderson RA, Leigh GJ, Pickett CJ. The chemistry of nitrogen fixation and models for the reactions of nitrogenase. Adv Inorg Chem Radiochem. 1983;27:197. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Allen AD, Harris RO, Loescher BR, Stevens JR, Whiteley RN. Dinitrogen Complexes of the Transition Metals. Chem Rev. 1973;73:11. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Richards RL. Reactions of small molecules at transition metal sites: Studies relevant to nitrogenase, an organometallic enzyme. Coord Chem Rev. 1996;154:83. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shilov AE. Catalytic reduction of molecular nitrogen in solutions. Russ Chem Bull Int Ed. 2003;52:2555. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schrock RR. Transition Metal Complexes that Contain a Triamidoamine Ligand. Acc Chem Res. 1997;30:9. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yandulov DV, Schrock RR. Reduction of Dinitrogen to Ammonia at a Well-Protected Reaction Site in a Molybdenum Triamidoamine Complex. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:6252. doi: 10.1021/ja020186x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yandulov DV, Schrock RR, Rheingold AL, Ceccarelli C, Davis WM. Synthesis and Reactions of Molybdenum Triamidoamine Complexes Containing Hexaisopropylterphenyl Substituents. Inorg Chem. 2003;42:796. doi: 10.1021/ic020505l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yandulov DV, Schrock RR. Catalytic Reduction of Dinitrogen to Ammonia at a Single Molybdenum Center. Science. 2003;301:76. doi: 10.1126/science.1085326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yandulov D, Schrock RR. Studies Relevant to Catalytic Reduction of Dinitrogen to Ammonia by Molybdenum Triamidoamine Complexes. Inorg Chem. 2005;44:1103. doi: 10.1021/ic040095w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Greco GE, O’Donoghue MB, Seidel SW, Davis WM, Schrock RR. Synthesis of [(Me3SiNCH2CH2)3N]3− and [(C6F5NCH2CH2)3N]3− Complexes of Molybdenum and Tungsten that Contain CO, Isocyanides, or Ethylene. Organometallics. 2000;19:1132. [Google Scholar]

- 29.W. W. Weare; unpublished results.

- 30.Chatt J, Pearman AJ, Richards RL. Diazenido complexes of molybdenum and tungsten. J Chem Soc, Dalton Trans. 1976:1520. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dobinson BC, Mason R, Robertson GB, Ugo R, Conti F, Morelli D, Cenini S, Bonati F. A dehydrodiimide complex of platinum(III): the reduction of cis-bistriphenylphosphineplatinum dichloride by hydrazine. Chem Commun. 1967:739. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sellmann D, Sutter J. In Quest of Competitive Catalysts for Nitrogenases and Other Metal Sulfur Enzymes. Acc Chem Res. 1997;30:460. [Google Scholar]

- 33.M. J. Byrnes; unpublished results.

- 34.Ritleng V, Yandulov DV, Weare WW, Schrock RR, Hock AR, Davis WM. Molybdenum Triamidoamine Complexes that Contain Hexa-tert-butylterphenyl, Hexamethylterphenyl, or p-Bromohexaisopropylterphenyl Substituents. An Examination of Some Catalyst Variations for the Catalytic Reduction of Dinitrogen. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:6150. doi: 10.1021/ja0306415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yandulov DV, Schrock RR. Synthesis of Tungsten Complexes that Contain Hexaisopropylterphenyl-Substituted Triamidoamine Ligands and Reactions Relevant to the Reduction of Dinitrogen to Ammonia. Canad J Chem. 2005;83:341. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Siemann S, Schneider K, Oley M, Mueller A. Characterization of a Tungsten-Substituted Nitrogenase Isolated from Rhodobacter capsulatus. Biochemistry. 2003;42:3846. doi: 10.1021/bi0270790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cummins CC, Schrock RR, Davis WM. Synthesis of Terminal Vanadium (V) Imido, Oxo, Sulfido, Selenido, and Tellurido Complexes by Imido Group or Chalcogenide Atom Transfer to Trigonal-Monopyramidal V[N3N] Inorg Chem. 1994;33:1448. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nomura K, Schrock RR, Davis WM. Synthesis of Vanadium(III), -(IV), and -(V) Complexes that Contain the Pentafluorophenyl-Substituted Triamidoamine Ligand, (C6F5NCH2CH2)3N. Inorg Chem. 1996;35:3695. [Google Scholar]

- 39.N. Smythe; unpublished results.

- 40.Schrock RR, Seidel SW, Mösch-Zanetti NC, Shih K-Y, O’Donoghue MB, Davis WM, Reiff WM. The Synthesis and Decomposition of Alkyl Complexes of Molybdenum(IV) that Contain a [(Me3SiNCH2CH2)3N]3− Ligand. Direct Detection of α Elimination Processes that are more than Six Orders of Magnitude Faster than β Elimination Processes. J Am Chem Soc. 1997;119:11876. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Seidel SW, Schrock RR, Davis WM. Tungsten and Molybdenum Alkyl or Aryl Complexes That Contain the [(C6F5NCH2CH2)3N]3- Ligand. Organometallics. 1998;17:1058. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Byrnes MJ, Dai X, Schrock RR, Hock AS, Müller P. Some Organometallic Chemistry of Molybdenum Complexes that Contain the [HIPTN3N]3− Triamidoamine Ligand, {[3,5-(2,4,6-i-Pr3C6H2)2C6H3NCH2CH2]3N}3−. Organometallics. 2005;24:4437. [Google Scholar]

- 43.X. Dai; unpublished results.

- 44.Laplaza CE, Johnson MJA, Peters JC, Odom AL, Kim E, Cummins CC, George GN, Pickering IJ. Dinitrogen Cleavage by Three-Coordinate Molybdenum(III) Complexes: Mechanistic and Structural Data. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118:8623. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Studt F, Tuczek F. Energetics and Mechanism of a Room-temperature Catalytic Process for Ammonia Synthesis (Schrock Cycle): Comparison with Biological Nitrogen Fixation. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2005;44:5639. doi: 10.1002/anie.200501485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]