Abstract

Via their capacities for proliferation and synthesis of matrix proteins such as collagen, fibroblasts are key effectors in the pathogenesis of fibrotic disorders such as idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) potently inhibits these functions in lung fibroblasts through receptor ligation and production of the second messenger cAMP, but the downstream pathways mediating such actions have not been fully characterized. We sought to investigate the roles of the cAMP effectors protein kinase A (PKA) and exchange protein activated by cAMP-1 (Epac-1) in modulating these two functions in primary human fetal lung IMR-90 fibroblasts. The specific roles of these two effector pathways were examined by treating cells with PKA-specific (6-bnz-cAMP) and Epac-specific (8-pCPT-2′-O-Me-cAMP) agonists, inhibiting PKA with the inhibitor KT 5720, overexpressing the PKA catalytic subunit, and silencing Epac-1 using short hairpin RNA. PGE2 inhibition of collagen I expression was mediated exclusively by activation of PKA, while inhibition of fibroblast proliferation was mediated exclusively by activation of Epac-1. PGE2 and Epac-1 inhibited cell proliferation through activation of the small GTPase Rap1, since decreasing Rap1 activity by transfection with Rap1GAP or the dominant-negative Rap1N17 prevented, and transfection with the constitutively active Rap1V12 mimicked, the anti-proliferative effects of PGE2. On the other hand, PKA inhibition of collagen was dependent on inhibition of protein kinase C-δ. The selective use of PKA and Epac-1 pathways to inhibit distinct aspects of fibroblast activation illustrate the pleiotropic ability of PGE2 to inhibit diverse fibroblast functions.

Keywords: proliferation, collagen, cAMP, pulmonary fibrosis

CLINICAL RELEVANCE

Our findings show that via divergent signaling pathways, prostaglandin E2 is able to inhibit distinct fibroblast functions. Understanding these pathways may provide novel therapeutic targets that can be used to limit fibroproliferation.

During wound healing, fibroblasts actively migrate and proliferate, synthesize and secrete extracellular matrix components such as collagen I, and differentiate into myofibroblasts, providing tensile forces for the contraction of wounds (1). The coordinated regulation of these diverse fibroblast functions is crucial to the normal resolution of injury. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, a devastating fibroproliferative disease with high mortality and little effective therapy (2), exemplifies the sequellae of unregulated fibroblast activation (3).

Prostaglandin (PG) E2 is a lipid mediator derived from the metabolism of arachidonic acid by cyclooxygenase-1 and -2, and is the major eicosanoid produced by alveolar epithelial cells (4) and lung fibroblasts (5). PGE2 is recognized to be an important “check” in fibroproliferation (6), as a local deficiency of PGE2 has been implicated in the pathogenesis of fibrotic lung disease in humans (5, 7) and animal models (8). Among the many anti-fibrotic actions of PGE2 is its ability to directly inhibit multiple fibroblast functions, including cell proliferation (9), collagen I synthesis (10, 11), and myofibroblast differentiation (12). These actions of PGE2 are transduced via ligation of the Gαs-coupled E prostanoid (EP) 2 receptor (13, 14), which is the most abundant of the four EP receptors expressed in fibroblasts and which leads to increases in cAMP production. However, the signaling events downstream from cAMP responsible for inhibiting specific activation parameters such as proliferation and collagen synthesis in lung fibroblasts are not well understood.

Protein kinase A (PKA) is the traditional effector for cAMP, and is responsible for a myriad of cell type–specific effects of this second messenger on cell growth and differentiation (15, 16). More recently, exchange protein activated by cAMP (Epac) has been identified as a novel cAMP effector (17, 18) and has opened new dimensions in the study of cAMP signaling (19). Indeed, some of the functions originally attributed to PKA are now recognized to be mediated by Epac. The two isoforms of Epac, Epac-1 and Epac-2, function as guanine nucleotide exchange factors for the small GTPase Rap1 (18), which has been shown to be involved in cell adhesion (20) and cell junction formation (21, 22). Signaling through PKA and Epac has been shown to elicit distinct (23), synergistic (24), or even antagonistic (25, 26) effects on cellular function.

The roles of the cAMP effectors PKA and Epac-1 in mediating the diverse effects of PGE2 in lung fibroblasts have never been investigated. Here we report that activation of Epac-1 and Rap1 is responsible for PGE2 inhibition of proliferation, while activation of PKA is responsible for inhibition of collagen expression. Our findings emphasize the independent regulation of these two critical fibroblast functions and provide novel insights into the cellular pathways used to control them by ligands such as PGE2 that signal via cAMP.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents

Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM), penicllin/streptomycin, OptiMEM, Lipofectamine LTX, Lipofectamine Plus, and Geneticin were obtained from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). Fetal bovine serum (FBS) and the serum-free growth medium SFM4MegaVir were purchased from Hyclone (Logan, UT). PGE2 was obtained from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI). Fibroblast growth factor (FGF) and platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) were supplied by R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN) and Cell Signaling (Danvers, MA), respectively. The PKA-specific cAMP analog 6-Bnz-cAMP and Epac-specific cAMP analog 8-pCPT-2′-O-Me-cAMP were purchased from Axxora (San Diego, CA). The PKA inhibitor KT 5720 and the protein kinase C (PKC)-δ inhibitor rottlerin were obtained from Biomol (Plymouth Meeting, PA). [3H]-thymidine and enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) reagent were obtained from GE Healthcare (Piscataway, NJ). Antibodies used for immunoblotting and their sources were as follows: collagen I, CedarLane Laboratories (Burlington, ON, Canada); Rap1 and Rap1GAP, Upstate (Temecula, CA); the catalytic subunit of PKA (PKA-Cα), BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA); Epac-1 and Epac-2, Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA); total and phosphorylated ERK1/2 and total and phosphorylated PKC-δ, Cell Signaling; α-tubulin, Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO).

Cell Culture and Transfection

IMR-90 cells, a primary human fetal lung fibroblast line (ATCC, Manassas, VA), were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and 100 U/ml penicillin/streptomycin. Normal and fibrotic adult lung fibroblasts (derived from lung tissue confirmed as histologically normal or with usual interstitial pneumonia [UIP], respectively) were isolated and grown as previously described (27). All patients provided informed consent and this study was approved by the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board. All cells were studied between passages 4 and 10. For transfection, cells were plated at 2 × 105 cells/well in 35-mm dishes and transfected using Lipofectamine LTX per manufacturer's protocol. Cells were maintained for at least 8 hours before medium was replaced with DMEM containing 10% FBS. For stable transfection, cells were selected using Geneticin 375 μg/ml for 48 hours and subsequently maintained with this antibiotic at 50 μg/ml. Plasmid for the constitutively active PKA-Cα was a gift from Dr. Michael D. Uhler (University of Michigan). Plasmids for Rap1GAP and RalGDS were a generous gift from Dr. Philip Stork (Oregon Health and Science University). Rap1N17 and Rap1V12 plasmids were a generous gift from Dr. Mark Philips (New York University). siRNA targets for Epac-1 were identified using a target finder algorithm from Ambion (Austin, TX). Sequences were then incorporated into hairpin constructs to make short hairpin (sh)RNA and cloned into a vector plasmid for use in stable transfection. pcDNA 3.1 (Invitrogen) was used as a control plasmid for experiments using Epac-1 shRNA, Rap1GAP, and Rap1N17 constructs; CMV-neo (Invitrogen) was used as a control plasmid for experiments using PKA-Cα constructs.

Cell Proliferation

Proliferation was measured by [3H]-thymidine incorporation as described previously (13). Cells were incubated in the presence or absence of growth factors – FGF (10 ng/ml), PDGF (10 ng/ml), or SFM4MegaVir – with the simultaneous addition of [3H]-thymidine for 18 h at 37°C. Uptake of [3H]-thymidine was measured via β-scintillation counter. Proliferation (dpm) in the presence of PGE2 or cAMP analogs is expressed as a percent of that determined in the absence of PGE2/cAMP analogs. Results from this method have been shown to correlate with direct cell counting in lung fibroblasts (13).

Collagen Expression

Collagen I expression was measured by immunoblot analysis using collagen I antibody (1:500) as previously described (13). Densitometric analysis of all bands was normalized to bands reflecting expression of α-tubulin. Each treatment condition is expressed as a percent of untreated control.

Rap1 Pulldown

Active Rap1 was assayed by pulldown of Rap1-GTP as previously described (28). All cells were treated with experimental agents for 15 minutes at 37°C before pulldown of Rap1-GTP with RalGDS coated beads. Pulled down (active) and total Rap1 were measured by immunoblot analysis and quantitated by densitometry.

Immunoblot Analysis

Cells were washed and lysed in lysis buffer (PBS containing 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 2 mM orthovanadate, and protease cocktail inhibitor; Roche). After separation by SDS-PAGE and transfer to nitrocellulose membranes, membranes were blocked in 5% bovine serum albumin in Tris-buffered solution with 0.1% Tween and incubated overnight at 4°C with respective primary antibodies (PKA-Cα,1:1,000; Epac-1, 1:500; Rap1, 1:500; Rap1GAP, 1:1,000; ERK1/2, 1:500; phospho-ERK1/2, 1:500; PKC-δ, 1:1,000; phospho-PKC-δ, 1:500; α-tubulin, 1:1,000). Bound primary antibodies were visualized with appropriate secondary antibody conjugated to horseradish peroxidase and developed with ECL reagent.

Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as mean ± standard error. Statistical tests (t test or ANOVA where appropriate) were performed using GraphPad Prism 4.0 (GraphPad Prism Software, San Diego, CA). Statistical significance was defined as P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Selective Effects of PKA and Epac Agonists

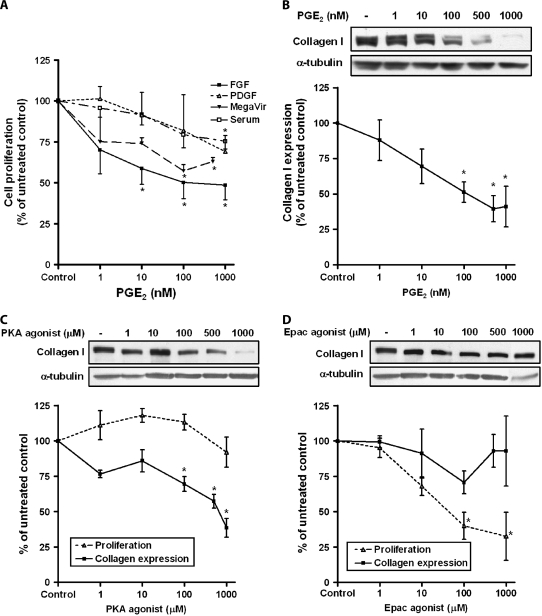

PGE2 is recognized to be a potent inhibitor of fibroblast function, and we first confirmed the dose-dependent inhibition of fibroblast proliferation (Figure 1A) and collagen expression (Figure 1B) by PGE2 in IMR-90 cells. It is notable that PGE2 inhibited proliferation regardless of whether cells were stimulated with FGF, PDGF, SFM4MegaVir, or serum. Work in our laboratory (13) and others (14) has shown that the inhibitory actions of PGE2 in lung fibroblasts are a result of increases in cAMP, mediated through the Gαs-coupled EP2 receptor; however, the downstream effectors of such actions are unknown. To determine which cAMP effector—PKA or Epac—is capable of inhibiting collagen expression and proliferation, fibroblasts were treated with varying concentrations of the selective PKA agonist 6-bnz-cAMP or the selective Epac agonist 8-pCPT-2′-O-Me-cAMP. The concentration of the cAMP analogs used were shown to have specificity for either PKA or Epac based on previous studies (24), and were not found to be toxic to cells, based on LDH assays (data not shown). The PKA agonist dose-dependently inhibited collagen expression but had no effect on proliferation (Figure 1C). Conversely, the Epac agonist elicited a dose-dependent decrease in proliferation but had no effect on collagen expression (Figure 1D). Although the figure only depicts data for FGF, this pattern of effects on proliferation by the two agonists was identical for the other mitogenic stimuli (PDGF, SFM4MegaVir, and 10% FBS) studied. These data suggest that collagen expression and proliferation in lung fibroblasts are selectively regulated by PKA and Epac, respectively.

Figure 1.

The protein kinase A (PKA) agonist selectively inhibits collagen expression, while the exchange protein activated by cAMP (Epac) agonist selectively inhibits cell proliferation. (A) IMR-90 fibroblasts were treated with varying concentrations of prostaglandin (PG)E2 overnight along with the indicated mitogen and proliferation was measured by [3H]-thymidine incorporation, as described in Materials and Methods (n = 3 for each data point). (B) Fibroblasts were treated in SFM4MegaVir with varying concentrations of PGE2 for 18 hours. Collagen expression was measured by immunoblot. Data from mean densitometric analysis of blots from five experiments is shown in the graph. Representative blot is shown above the graph. (C) Cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of the selective PKA agonist, 6-bnz-cAMP, in SFM4MegaVir (collagen) or FGF 10 ng/ml (proliferation) for 18 hours. Collagen expression (n = 6) and proliferation (n = 3) were measured and expressed as a percent of untreated control. Representative immunoblot for collagen is shown. (D) Cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of the selective Epac agonist, 8-pCPT-2′-O-Me-cAMP in SFM4MegaVir (collagen) or FGF 10 ng/ml (proliferation) for 18 hours. Collagen expression (n = 5) and proliferation (n = 3) were measured. Representative immunoblot for collagen is shown. All data points are expressed as a percent of no-treatment control, mean ± SE. *P < 0.05 relative to no-treatment control.

Central Role of PKA in PGE2-Dependent Inhibition of Collagen Expression

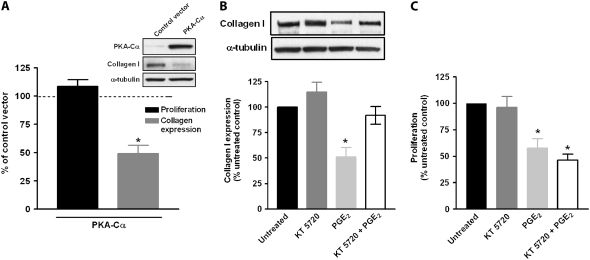

To further explore the actions of PKA, cells were transfected with a construct encoding the constitutively active PKA-Cα (Figure 2A, inset). In keeping with the agonist data, cells expressing PKA-Cα exhibited a reduction in collagen expression, but not in proliferation (Figure 2A). To determine whether PGE2-mediated inhibition of collagen expression is dependent on PKA, fibroblasts were pretreated with the PKA inhibitor KT 5720 for 30 minutes before the addition of PGE2. Treatment with the PKA inhibitor was able to block the inhibitory effects of PGE2 on collagen expression (Figure 2B) but not proliferation (Figure 2C).

Figure 2.

PGE2 inhibition of collagen expression is mediated through PKA. (A) Fibroblasts were transiently transfected with plasmid expressing the constitutively active catalytic subunit of PKA, Cα. Expression of PKA-Cα is shown in the inset. Collagen expression (n = 6) and cell proliferation (n = 3) of PKA-Cα transfected cells were compared relative to cells transfected with control vector, CMV-neo. *P < 0.05 relative to control vector. (B) Cells stimulated with SMF4MegaVir were pre-treated ± the PKA inhibitor KT 5720 0.1 μM for 30 minutes. PGE2 (500 nM) was subsequently added and incubated for an additional 18 hours. Collagen expression (n = 4) was measured as previously described. Representative blot is shown above graph. (C) Cells treated as in B were analyzed for proliferation. Data represent mean and SE of five independent experiments. *P < 0.05 relative to no-treatment control.

Central Role of Epac-1 in PGE2-Dependent Inhibition of Fibroblast Proliferation

Our previous work showed that Epac-1 was expressed in lung fibroblasts (13). By contrast, immunoblotting for Epac-2 revealed that Epac-2 was not expressed in these cells. To determine whether PGE2-mediated inhibition of fibroblast proliferation is dependent on Epac-1, we silenced Epac-1 expression by stably transfecting cells with shRNA for Epac-1 (Figure 3A). PGE2 inhibited proliferation in SFM4MegaVir in cells transfected with the pcDNA 3.1 control vector, but not in cells transfected with Epac-1 shRNA (Figure 3B). Similar results were seen in cells stimulated with PDGF (10 ng/ml) or FGF (10 ng/ml) (data not shown). There was no difference, however, in PGE2 inhibition of collagen expression between cells transfected with pcDNA 3.1 or Epac-1 shRNA (Figure 3C). When taken together with the effects of the Epac agonist, these data suggest that Epac-1 mediates PGE2 inhibition of cell proliferation but not collagen expression.

Figure 3.

PGE2 inhibition of fibroblast proliferation is mediated through Epac-1. Fibroblasts were stably transfected with plasmids containing Epac-1 shRNA or control vector, pcDNA 3.1. (A) Epac-1 expression is shown. (B) Transfected cells were treated ± PGE2 (500 nM) for 18 hours in SFM4MegaVir and assayed for proliferation. Data are expressed as percent of no-PGE2 control, n = 3. (C) Transfected cells were treated ± PGE2 (500 nM) for 18 hours and assayed for collagen. Data are expressed as percent of no-PGE2 control (n = 6, representative immunoblot is shown in the inset above). *P < 0.05 relative to no-treatment control.

Rap1 as a Target of Epac-1

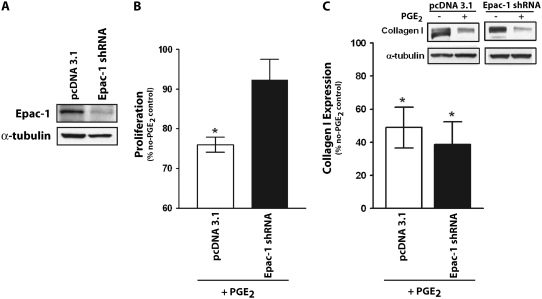

Rap1 is a GTPase that activates several downstream signals involved in cell growth (29), and is a commonly described target for Epac (18). We found that both PGE2 and the Epac agonist stimulated Rap1 activity, as measured by the RalGDS pulldown of active GTP-loaded Rap1, whereas the PKA agonist actually had an inhibitory effect on Rap1 activity (Figure 4A). Furthermore, PGE2 did not stimulate Rap1 activity in Epac-1–silenced cells (Figure 4B), suggesting that PGE2 activation of Rap1 is dependent on Epac-1. To determine if the activation of Rap1 by PGE2/Epac-1 is necessary for their inhibitory effects on proliferation, we transfected cells to express Rap1-GAP, a GTPase-activating protein that promotes the conversion of active Rap1-GTP to inactive Rap1-GDP (Figure 4C), or Rap1N17, a dominant-negative form of Rap1. As expected, PGE2 was unable to activate Rap1 in either Rap1GAP- or Rap1N17-transfected cells (Figure 4D). Importantly, neither PGE2 nor the Epac agonist was able to inhibit SFM4MegaVir-stimulated cell proliferation under either of these conditions (Figure 4E), suggesting that Rap1 is critical to the inhibition of proliferation by PGE2/Epac-1. Similar patterns were seen with the mitogens PDGF (10 ng/ml) or FGF (10 ng/ml) (data not shown). The inhibitory role of Rap1 was further supported by transfecting cells with Rap1V12, a constitutively active Rap1 construct, which resulted in a 54.2 ± 3.8% decrease in cell proliferation compared with cells transfected with a control vector (n = 3).

Figure 4.

Rap1 is a critical target of Epac-1 in PGE2-mediated inhibition of proliferation. (A) Fibroblasts were treated for 15 minutes with PGE2 (500 nM), the specific Epac agonist 8-pCPT-2′-O-Me-cAMP, or the specific PKA agonist 6-bnz-cAMP for 15 minutes. Active Rap1 (Rap1-GTP) was assayed by pulldown as described in Materials and Methods. Representative blot of four independent experiments is shown. Fold change in activity (measured by densitometry of Rap1-GTP relative to untreated control) for PGE2 (500 nM), Epac agonist (100 μM), and PKA agonist (100 μM) is expressed graphically (n = 4). (B) Active Rap1 (Rap1-GTP) was measured in cells stably transfected with control vector (pcDNA 3.1) or Epac-1 shRNA and treated ± PGE2 (500 nM) for 15 minutes. Representative blot of four independent experiments is shown. (C) Cells were transfected with Rap1GAP, a GTPase activating protein that inactivates Rap1. Expression of Rap1GAP is shown. (D) Rap1-GTP was assayed in cells transfected with control vector (pcDNA 3.1), Rap1GAP, or the dominant-negative construct Rap1N17 treated for 15 minutes ± PGE2 (500 nM). Representative blot of three independent experiments is shown. (E) Cells transfected with control vector (pcDNA 3.1), Rap1GAP, Rap1N17, or Rap1V12 were treated ± PGE2 (500 nM) or the Epac agonist 8-pCPT-2′-O-Me-cAMP (100 μM) in SFM4MegaVir for 18 hours and proliferation was measured; results are expressed as a percent of no-treatment control. n = 5 for pcDNA 3.1 and Rap1GAP, n = 3 for Rap1N17 and Rap1V12. *P < 0.05 relative to no-treatment control; #P < 0.05 relative to untreated control vector. (F) Cells were treated at the indicated time points with the mitogen SFM4MegaVir alone or with the addition of PGE2 (500 nM), the Epac agonist 8-pCPT-2′-O-Me-cAMP (100 μM), or the PKA agonist 6-bnz-cAMP (100 μM) and assayed for phospho-ERK1/2 by immunoblot. Representative blot is shown with fold increase in phospho-ERK 1/2 (as quantitated by densitometry relative to total ERK 1/2) compared with no treatment shown below each lane. Values represent mean of three independent experiments with SE below.

As many growth factors promote proliferation by activating ERK1/2 (30, 31), and Rap1 has been shown to inhibit ERK1/2 in certain cell types (32, 33), we considered ERK1/2 inhibition as a candidate target for the selective inhibitory effects of PGE2/Epac-1. However, assessment of phospho-ERK1/2 revealed that neither PGE2, the PKA agonist, nor the Epac agonist was able to inhibit the initial mitogen-stimulated increases in phospho-ERK 1/2 (by either SFM4MegaVir [shown in Figure 4F] or FGF). At the 30-minute time point, there was less phospho-ERK 1/2 in cells treated with PGE2, the PKA agonist, and the Epac agonist compared with SFM4MegaVir alone, but the similar result among all three of these agents argues against this being able to explain the selective anti-proliferative effects of PGE2 and Epac-1. Furthermore, all three agonists were able to stimulate ERK 1/2 activity when given in the absence of any mitogen (data not shown). These findings suggest that PGE2, Epac-1, and Rap1 inhibit cell proliferation independent of effects on ERK1/2 activity.

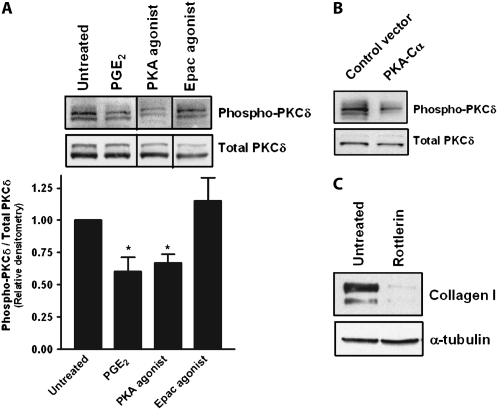

PKC-δ as a Target of PKA

PKC-δ activation is well recognized to promote fibroblast collagen synthesis (34, 35), and response elements for PKC-δ have been identified on the α2(I) collagen gene (34, 36). Since PKA and PKC often signal opposing cellular events (37, 38), and since the collagen I gene does not have a cAMP response element (CRE) for direct PKA targeting, we hypothesized that PGE2/PKA inhibition of collagen expression occurred indirectly through inhibition of PKC-δ. PGE2 and the PKA agonist, but not the Epac agonist, inhibited PKC-δ phosphorylation (Figure 5A). Cells transfected with the catalytic subunit of PKA also showed diminished PKC-δ phosphorylation (Figure 5B). Inhibition with the specific PKC-δ inhibitor rottlerin resulted in decreased collagen expression (Figure 5C). These data, along with the known role of PKC-δ in collagen synthesis, suggest that PGE2/PKA inhibits collagen through a decrease in PKC-δ activity.

Figure 5.

PGE2 and PKA-mediated inhibition of collagen expression occurs through inhibition of PKC-δ. (A) IMR-90 cells were treated with PGE2 (500 nM), the specific Epac agonist 8-pCPT-2′-O-Me-cAMP (100 μM), or the specific PKA agonist 6-bnz-cAMP (100 μM) for 60 minutes, and lysates were immunoblotted for total and phosphorylated PKC-δ. Mean ± SE of relative densitometry is displayed (n = 3) with representative blot shown above. (B) Cells transfected with the catalytic subunit of PKA were assayed for total and phosphorylated PKC-δ. Representative blot of three independent experiments is shown. (C) Cells were treated with the PKC-δ inhibitor rottlerin (10 μM) for 18 hours and collagen expression was measured. Representative blot of three independent experiments is shown.

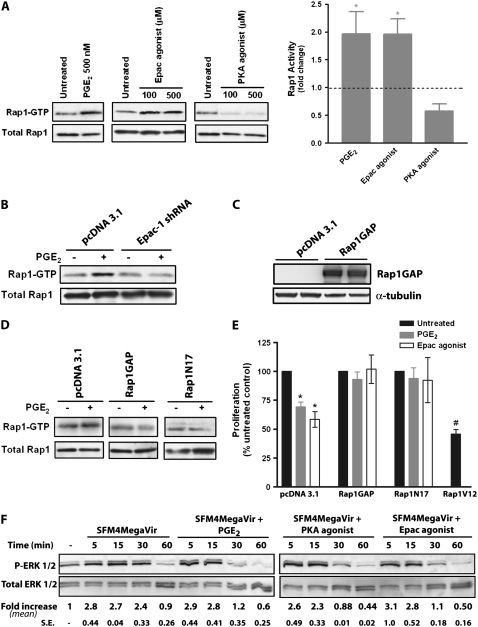

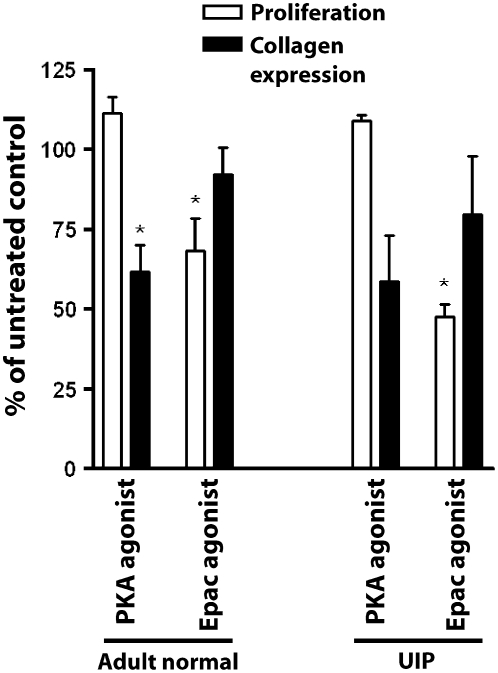

Selective Roles of PKA and Epac-1 in Primary Adult Fibroblasts

To extend our findings in IMR-90 cells to adult lung cells, fibroblasts from histologically normal and fibrotic lung (confirmed by pathologists to show a pattern of UIP) were isolated, cultured, and treated with the PKA agonist 6-bnz-cAMP (100 μM) or the Epac agonist 8-pCPT-2′-O-Me-cAMP (100 μM). Cells were assayed for collagen I expression and cell proliferation (Figure 6). Consistent with the findings in IMR-90 cells, both normal and UIP fibroblasts exhibited similar patterns of PKA-selective inhibition of collagen expression and Epac-selective inhibition of cell proliferation.

Figure 6.

The selective inhibitory roles of PKA and Epac agonists are observed in primary adult normal and fibrotic (usual interstitial pneumonia [UIP]) lung fibroblasts. Fibroblasts from histologically normal (n = 3) and UIP (n = 4) lung tissue were grown as described in Materials and Methods and treated with either the PKA agonist (6-bnz-cAMP, 100 μM) or Epac agonist (8-pCPT-2′-O-Me-cAMP, 100 μM) for 18 hours in SFM4MegaVir and assayed for collagen expression and cell proliferation. *P < 0.05 relative to untreated control.

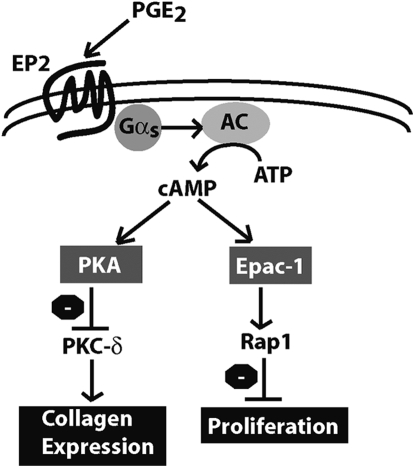

DISCUSSION

Fibroblast proliferation and extracellular matrix production are controlled by divergent and sometimes opposing signals (39). However, PGE2 potently inhibits both fibroblast proliferation and matrix synthesis through a common second messenger, cAMP (13, 14, 40). How PGE2/cAMP mediates inhibition of multiple fibroblast functions has never been elucidated. Our studies show for the first time that PGE2 uses distinct cAMP effectors—PKA and Epac-1—to inhibit collagen expression and cell proliferation, respectively (Figure 7). Importantly, these specific modes of regulation were observed in both fetal lung cells as well as primary adult fibroblasts from histologically normal and UIP lung tissue.

Figure 7.

PGE2 inhibits lung fibroblast collagen expression and proliferation via independent cAMP effectors. PGE2 inhibition of fibroblast collagen expression and proliferation share a common proximal signaling pathway via ligation of EP2, activation of the G-stimulatory protein Gαs, activation of adenyl cyclase (AC), and increase in intracellular cAMP. The activation of PKA, however, is responsible for the inhibition of collagen expression via inhibition of PKC-δ, whereas activation of Epac-1 leads to Rap1 activation and inhibition of proliferation.

For many years, PKA was regarded as the “classic” effector responsible for diverse cAMP-mediated functions. These include both pro- and anti-proliferative effects, depending on cell type. In NIH3T3 cells, the antiproliferative effects of cAMP have been attributed to activation of PKA and its effects on Rap1 (33, 41). The discovery of Epac, however, has opened up a new dimension in studying cAMP-mediated cell signaling (18, 19). Epac has been best characterized to be important in cell adhesion (20) and cell junction formation (21, 22), and has been shown to have pro-proliferative effects in endothelial cells (42), macrophages (43), thyroid cells (44), and osteoblasts (45). Our findings in primary lung fibroblasts, however, show that PGE2 has anti-proliferative effects through Epac-1, independent of PKA. These findings were independent of the growth factor/medium conditions used. This novel anti-proliferative role for Epac-1 in primary lung fibroblasts is supported by a recent study that suggests Epac may also be anti-proliferative in bronchial smooth muscle cells (46). The ability of Epac-1 (and subsequent activation of Rap1) to play divergent roles in mesenchymal cells versus other cell types illustrates how these cells can exhibit dichotomous responses to common signaling pathways.

We further identified Rap1 as the downstream target of Epac-1 responsible for inhibiting proliferation. Interestingly, in other cell types, such as NIH3T3 cells, Rap1 can inhibit proliferation, but is activated by a PKA-dependent pathway that results in activation of a different exchange factor, C3G (33). It is interesting to note that in our experimental system, PKA actually inhibited Rap1 activation. These differing results might be related to the fact that NIH3T3 cells are immortalized as opposed to the primary lung fibroblasts used in our experiments, but it also illustrates that in addition to cells being able to use divergent signaling pathways, a given pathway (PKA activation in this example) may produce opposite effects on downstream targets depending on cell type. The net effect (i.e., whether Rap1 is activated or inhibited by Epac-1 or PKA, respectively), may depend on the spatiotemporal location of these molecules within a given cell during response to a specific signal.

Rap1 inhibition of cell growth has previously been attributed to the inhibition of b-Raf and ERK 1/2 (32). A surprising observation, however, was that neither PGE2, PKA, nor Epac-1 was able to inhibit the activation of ERK1/2 by growth factors in IMR-90 cells. In fact, by themselves, they were able to activate ERK 1/2. This suggests that inhibition of fibroblast proliferation by PGE2, Epac-1, and Rap1 proceeded independent of ERK1/2 participation. ERK1/2 independence in Epac-1/Rap1 inhibition of proliferation has been described in other experimental systems (47). We have not identified how Epac-1/Rap1 inhibits proliferation in our experimental system, but interactions of Epac-1 with microtubules and cytoskeleton have been reported (48, 49) and we speculate that inhibition may occur through direct interaction of Epac-1/Rap1 with such structures responsible for cell division. This may also explain how Epac-1 inhibits proliferation in response to a gamut of growth factors used to stimulate proliferation. Further studies of the downstream targets for both Epac-1/Rap1 are needed.

The collagen I gene does not have a CRE, suggesting an indirect mode of action for PKA in inhibiting collagen expression. PKC-δ has been described to be an important activator in collagen synthesis (34, 35). Given our findings that PKA inhibited PKC-δ activity and the precedent for PKA and PKC having opposing roles (37, 38), we suggest that the mechanism for PKA inhibition of collagen synthesis occurs through down-regulation of PKC-δ. This is supported by data with inhibitors of PKC-δ which down-regulate collagen expression (34, 35). Whether PKA may target other signaling molecules that down-regulate collagen synthesis independent of PKC-δ is unknown. We do not know how PKA inhibits PKC-δ but speculate that it may be through PKA inhibition of phospholipase C (37), a key enzyme in the activation of PKCδ.

Our conclusion regarding the divergent roles of PKA and Epac-1 is based on a variety of experimental approaches, including pharmacologic agonists, genetic overexpression of PKA, pharmacologic inhibitors of PKA, and shRNA against Epac. The doses of pharmacologic agents were chosen based on studies of prior specificity, and LDH assays were performed to rule out cytotoxicity. The fact that different cAMP effectors were able to inhibit one cell function but not the other excludes the possibility that the PGE2 effects are the result of a single common process, such as apoptosis.

While some studies have identified situations in which PKA and Epac-1 act synergistically (24, 44), or even exert opposing effects (25) on differentiation and survival, our studies showed these effectors to exert distinct and independent effects on different cell functions in human lung fibroblasts. The potential significance of this finding is found in recent work from our laboratory which has shown that lung fibroblasts from many patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis exhibit resistance to PGE2 in inhibition of either collagen expression or proliferation, but not both (27). The data presented here would suggest that the discordance in PGE2 responses of these two functions could be due to defects specific to either PKA or Epac-1 in individual patients. Understanding the mechanisms by which distinct fibroblast activation phenotypes are controlled may assist our understanding of the pathogenesis of fibrotic lung disease as well as the development of therapeutic agents.

PGE2 is well known to inhibit other fibroblast functions as well, including fibroblast migration (50), myofibroblast differentiation (12), and contraction. Many of these functions are also regulated through cAMP; however, the role of PKA versus Epac-1 in modulating such functions is unknown and will require further investigation.

In conclusion, PGE2 inhibition of collagen expression and proliferation are mediated through distinct cAMP effector pathways. PKA activation and the subsequent inhibition of PKC-δ lead to inhibition of collagen expression while Epac-1 and subsequent Rap1 activation lead to inhibition of proliferation. The activation of these distinct pathways provides another layer by which PGE2 can exert diverse effects within a given cell.

Acknowledgments

The authors graciously thank Dr. Michael D. Uhler for providing PKA-Cα plasmids, Dr. Philip Stork for providing Rap1GAP and RalGDS plasmids, and Dr. Mark Philips for providing Rap1N17 and Rap1V12 plasmids. The authors thank Drs. David M. Aronoff, Thomas G. Brock, and Carlos H. Serezani for their insightful discussions.

This work was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grant P50-HL-56402 (to M.P.G.) and by NIH T32-HL-07749 (to S.K.H.).

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1165/rcmb.2008-0080OC on April 17, 2008

Conflict of Interest Statement: None of the authors has a financial relationship with a commercial entity that has an interest in the subject of this manuscript.

References

- 1.Martin P. Wound healing: aiming for perfect skin regeneration. Science 1997;276:75–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society. American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society International Multidisciplinary Consensus Classification of the Idiopathic Interstitial Pneumonias. This joint statement of the American Thoracic Society (ATS), and the European Respiratory Society (ERS) was adopted by the ATS board of directors, June 2001 and by the ERS Executive Committee, June 2001. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002;165:277–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Selman M, King TE, Pardo A. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: prevailing and evolving hypotheses about its pathogenesis and implications for therapy. Ann Intern Med 2001;134:136–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chauncey JB, Simon RH, Peters-Golden M. Rat alveolar macrophages synthesize leukotriene B4 and 12-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid from alveolar epithelial cell-derived arachidonic acid. Am Rev Respir Dis 1988;138:928–935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wilborn J, Crofford LJ, Burdick MD, Kunkel SL, Strieter RM, Peters-Golden M. Cultured lung fibroblasts isolated from patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis have a diminished capacity to synthesize prostaglandin E2 and to express cyclooxygenase-2. J Clin Invest 1995;95:1861–1868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peters-Golden M. When defenses against fibroproliferation fail: spotlight on an axis of prophylaxis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2003;168:1141–1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vancheri C, Sortino MA, Tomaselli V, Mastruzzo C, Condorelli F, Bellistri G, Pistorio MP, Canonico PL, Crimi N. Different expression of TNF-alpha receptors and prostaglandin E(2)Production in normal and fibrotic lung fibroblasts: potential implications for the evolution of the inflammatory process. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2000;22:628–634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hodges RJ, Jenkins RG, Wheeler-Jones CP, Copeman DM, Bottoms SE, Bellingan GJ, Nanthakumar CB, Laurent GJ, Hart SL, Foster ML, et al. Severity of lung injury in cyclooxygenase-2-deficient mice is dependent on reduced prostaglandin E(2) production. Am J Pathol 2004;165:1663–1676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Elias JA, Rossman MD, Zurier RB, Daniele RP. Human alveolar macrophage inhibition of lung fibroblast growth: a prostaglandin-dependent process. Am Rev Respir Dis 1985;131:94–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saltzman LE, Moss J, Berg RA, Hom B, Crystal RG. Modulation of collagen production by fibroblasts: effects of chronic exposure to agonists that increase intracellular cyclic AMP. Biochem J 1982;204:25–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fine A, Poliks CF, Donahue LP, Smith BD, Goldstein RH. The differential effect of prostaglandin E2 on transforming growth factor-beta and insulin-induced collagen formation in lung fibroblasts. J Biol Chem 1989;264:16988–16991. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kolodsick JE, Peters-Golden M, Larios J, Toews GB, Thannickal VJ, Moore BB. Prostaglandin E2 inhibits fibroblast to myofibroblast transition via E. prostanoid receptor 2 signaling and cyclic adenosine monophosphate elevation. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2003;29:537–544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang SK, Wettlaufer SH, Hogaboam CM, Aronoff DM, Peters-Golden M. Prostaglandin E2 inhibits collagen expression and proliferation in patient-derived normal lung fibroblasts via E prostanoid 2 receptor and cAMP signaling. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2007;292:L405–L413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Choung J, Taylor L, Thomas K, Zhou X, Kagan H, Yang X, Polgar P. Role of EP2 receptors and cAMP in prostaglandin E2 regulated expression of type I collagen alpha1, lysyl oxidase, and cyclooxygenase-1 genes in human embryo lung fibroblasts. J Cell Biochem 1998;71:254–263. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cho-Chung YS, Nesterova M, Becker KG, Srivastava R, Park YG, Lee YN, Cho YS, Kim MK, Neary C, Cheadle C. Dissecting the circuitry of protein kinase A and cAMP signaling in cancer genesis: antisense, microarray, gene overexpression, and transcription factor decoy. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2002;968:22–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stork PJ, Schmitt JM. Crosstalk between cAMP and MAP kinase signaling in the regulation of cell proliferation. Trends Cell Biol 2002;12:258–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kawasaki H, Springett GM, Mochizuki N, Toki S, Nakaya M, Matsuda M, Housman DE, Graybiel AM. A family of cAMP-binding proteins that directly activate Rap1. Science 1998;282:2275–2279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.de Rooij J, Zwartkruis FJ, Verheijen MH, Cool RH, Nijman SM, Wittinghofer A, Bos JL. Epac is a Rap1 guanine-nucleotide-exchange factor directly activated by cyclic AMP. Nature 1998;396:474–477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bos JL. Epac: a new cAMP target and new avenues in cAMP research. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2003;4:733–738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rangarajan S, Enserink JM, Kuiperij HB, de Rooij J, Price LS, Schwede F, Bos JL. Cyclic AMP induces integrin-mediated cell adhesion through Epac and Rap1 upon stimulation of the beta 2-adrenergic receptor. J Cell Biol 2003;160:487–493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fukuhara S, Sakurai A, Sano H, Yamagishi A, Somekawa S, Takakura N, Saito Y, Kangawa K, Mochizuki N. Cyclic AMP potentiates vascular endothelial cadherin-mediated cell-cell contact to enhance endothelial barrier function through an Epac-Rap1 signaling pathway. Mol Cell Biol 2005;25:136–146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cullere X, Shaw SK, Andersson L, Hirahashi J, Luscinskas FW, Mayadas TN. Regulation of vascular endothelial barrier function by Epac, a cAMP-activated exchange factor for Rap GTPase. Blood 2005;105:1950–1955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang Z, Dillon TJ, Pokala V, Mishra S, Labudda K, Hunter B, Stork PJ. Rap1-mediated activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinases by cyclic AMP is dependent on the mode of Rap1 activation. Mol Cell Biol 2006;26:2130–2145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Christensen AE, Selheim F, de Rooij J, Dremier S, Schwede F, Dao KK, Martinez A, Maenhaut C, Bos JL, Genieser HG, et al. cAMP analog mapping of Epac1 and cAMP kinase: discriminating analogs demonstrate that Epac and cAMP kinase act synergistically to promote PC-12 cell neurite extension. J Biol Chem 2003;278:35394–35402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mei FC, Qiao J, Tsygankova OM, Meinkoth JL, Quilliam LA, Cheng X. Differential signaling of cyclic AMP: opposing effects of exchange protein directly activated by cyclic AMP and cAMP-dependent protein kinase on protein kinase B activation. J Biol Chem 2002;277:11497–11504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kiermayer S, Biondi RM, Imig J, Plotz G, Haupenthal J, Zeuzem S, Piiper A. Epac activation converts cAMP from a proliferative into a differentiation signal in PC12 cells. Mol Biol Cell 2005;16:5639–5648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huang SK, Wettlaufer SH, Hogaboam CM, Flaherty KR, Martinez FJ, Myers JL, Colby TV, Travis WD, Toews GB, Peters-Golden M. Variable prostaglandin E2 resistance in fibroblasts from patients with usual interstitial pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2008;177:66–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Serezani CH, Chung J, Ballinger MN, Moore BB, Aronoff DM, Peters-Golden M. Prostaglandin e2 suppresses bacterial killing in alveolar macrophages by inhibiting NADPH oxidase. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2007;37:562–570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kitayama H, Sugimoto Y, Matsuzaki T, Ikawa Y, Noda M. A ras-related gene with transformation suppressor activity. Cell 1989;56:77–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mansour SJ, Matten WT, Hermann AS, Candia JM, Rong S, Fukasawa K, Vande Woude GF, Ahn NG. Transformation of mammalian cells by constitutively active MAP kinase kinase. Science 1994;265:966–970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Blenis J. Signal transduction via the MAP kinases: proceed at your own RSK. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1993;90:5889–5892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dugan LL, Kim JS, Zhang Y, Bart RD, Sun Y, Holtzman DM, Gutmann DH. Differential effects of cAMP in neurons and astrocytes: role of B-raf. J Biol Chem 1999;274:25842–25848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schmitt JM, Stork PJ. PKA phosphorylation of Src mediates cAMP's inhibition of cell growth via Rap1. Mol Cell 2002;9:85–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jimenez SA, Gaidarova S, Saitta B, Sandorfi N, Herrich DJ, Rosenbloom JC, Kucich U, Abrams WR, Rosenbloom J. Role of protein kinase C-delta in the regulation of collagen gene expression in scleroderma fibroblasts. J Clin Invest 2001;108:1395–1403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang L, Keane MP, Zhu LX, Sharma S, Rozengurt E, Strieter RM, Dubinett SM, Huang M. Interleukin-7 and transforming growth factor-beta play counter-regulatory roles in protein kinase C-delta-dependent control of fibroblast collagen synthesis in pulmonary fibrosis. J Biol Chem 2004;279:28315–28319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jinnin M, Ihn H, Yamane K, Mimura Y, Asano Y, Tamaki K. Alpha2(I) collagen gene regulation by protein kinase C signaling in human dermal fibroblasts. Nucleic Acids Res 2005;33:1337–1351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu M, Simon MI. Regulation by cAMP-dependent protein kinease of a G-protein-mediated phospholipase C. Nature 1996;382:83–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang XF, Guo SZ, Lu KH, Li HY, Li XD, Zhang LX, Yang L. Different roles of PKC and PKA in effect of interferon-gamma on proliferation and collagen synthesis of fibroblasts. Acta Pharmacol Sin 2004;25:1320–1326. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Roberts AB, Anzano MA, Wakefield LM, Roche NS, Stern DF, Sporn MB. Type beta transforming growth factor: a bifunctional regulator of cellular growth. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1985;82:119–123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu X, Ostrom RS, Insel PA. cAMP-elevating agents and adenylyl cyclase overexpression promote an antifibrotic phenotype in pulmonary fibroblasts. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2004;286:C1089–C1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pursiheimo JP, Kieksi A, Jalkanen M, Salmivirta M. Protein kinase A balances the growth factor-induced Ras/ERK signaling. FEBS Lett 2002;521:157–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fang Y, Olah ME. Cyclic AMP-dependent, protein kinase A-independent activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 following adenosine receptor stimulation in human umbilical vein endothelial cells: role of exchange protein activated by cAMP 1 (Epac1). J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2007;322:1189–1200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Misra UK, Pizzo SV. Coordinate regulation of forskolin-induced cellular proliferation in macrophages by protein kinase A/cAMP-response element-binding protein (CREB) and Epac1-Rap1 signaling: effects of silencing CREB gene expression on Akt activation. J Biol Chem 2005;280:38276–38289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hochbaum D, Hong K, Barila G, Ribeiro-Neto F, Altschuler DL. Epac, in synergy with PKA, is required for cAMP-mediated mitogenesis. J Biol Chem 2008;283:4464–4468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fujita T, Meguro T, Fukuyama R, Nakamuta H, Koida M. New signaling pathway for parathyroid hormone and cyclic AMP action on extracellular-regulated kinase and cell proliferation in bone cells. Checkpoint of modulation by cyclic AMP. J Biol Chem 2002;277:22191–22200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kassel KM, Wyatt TA, Panettieri RA Jr, Toews ML. Inhibition of human airway smooth muscle cell proliferation by beta 2-adrenergic receptors and cAMP is PKA independent: evidence for EPAC involvement. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2008;294:L131–L138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McKenzie FR, Pouyssegur J. cAMP-mediated growth inhibition in fibroblasts is not mediated via mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase (ERK) inhibition: cAMP-dependent protein kinase induces a temporal shift in growth factor-stimulated MAP kinases. J Biol Chem 1996;271:13476–13483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Magiera MM, Gupta M, Rundell CJ, Satish N, Ernens I, Yarwood SJ. Exchange protein directly activated by cAMP (EPAC) interacts with the light chain (LC) 2 of MAP1A. Biochem J 2004;382:803–810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mei FC, Cheng X. Interplay between exchange protein directly activated by cAMP (Epac) and microtubule cytoskeleton. Mol Biosyst 2005;1:325–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.White ES, Atrasz RG, Dickie EG, Aronoff DM, Stambolic V, Mak TW, Moore BB, Peters-Golden M. Prostaglandin E(2) inhibits fibroblast migration by E-prostanoid 2 receptor-mediated increase in PTEN activity. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2005;32:135–141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]