Abstract

A retrospective study evaluating complications in 2,233 consecutive patients of subaxial cervical disorders treated with an anterior cervical locking plate was performed, and recommendations for prevention and treatment were made. The average length of follow-up was 1.3 years. Any loosening or breaking of the plates and screws or malpositions that threatened tracheoesophageal or neurovascular structures were defined as the complications. There were 239 cases (10.7%) with different kinds of complications. The complications included oblique plating in 56 cases in which the screw could irritate the nerve root. Screws were driven into the disc space in four cases, which ultimately led to plate loosening. Screws penetrated the endplate or passed excessively close to it producing a triangle fracture in 19 cases. Loosening or breaking of the plate and the screw was found in 115 cases. These phenomena were always associated with non-union. Three oesophageal perforations occurred and conservative treatments proved effective. Finally, overlong plates impinged on the adjacent level in 14 cases and promoted disc degeneration ultimately leading to revision surgery. Good training and careful operation may help to decrease the complication rate. Most hardware complications are not symptomatic and can be treated conservatively. Only a few of them need immediate reoperation.

Résumé

Nous avons réalisé une étude rétrospective de 2,233 patients consécutifs, traités par plaques cervicales verrouillées pour divers problèmes cervicaux. Le suivi moyen a été de 1.3 ans. Nous n’avons observé aucun démontage ni aucune fracture de matériel. Les malpositions de la plaque avec des lésions trachéo oesophagiennes ou neurovasculaires ont été répertoriées comme complications. Celles-ci ont été au nombre de 239 (10.7%), notamment une malposition de plaque implantée obliquement avec une irritation des racines nerveuses. Les vis étaient dans l’espace inter discal dans 4 cas avec un démontage dans les suites. Les anomalies au niveau de la plaque ont été retrouvées dans 115 cas. Celles-ci sont toujours associées à une pseudarthrose. Nous avons observé trois perforations de l’œsophage qui ont été traitées de façon conservatoire. Un conflit avec la plaque ou une dégénération discale du disque adjacent est survenu 14 fois. Avec la courbe d’apprentissage, les résultats devraient s’améliorer et le taux de complication diminuer. La plupart des complications dues au matériel n’ont pas entraîné de symptômes et n’ont pas été traitées.

Introduction

Since Böhler [2] used the anterior cervical plate to treat cervical fractures and dislocations in 1980, the anterior cervical plate has been developed a great deal. At the early phase, the complication rate of the unlocked plate was relatively high, especially loosening of the screws and the plates [1, 3, 5, 6, 12, 15]. Locking plates are now being used to stabilise cervical spinal trauma, or used in combination with cages or meshes after discectemy or corpectemy in cervical degenerative diseases or tumours [4, 9, 14, 17, 18, 20, 21]. There are many papers reporting the indications, techniques and results of cervical locking plates [1–21]. However, few studies have focused on the complications of the anterior cervical locking plates. In this respective review of cases, the complications of anterior cervical locking plates applied in 2,233 cases were collected and evaluated, and prevention and treatment recommendations were made.

Materials and methods

The complications of anterior cervical locking plates in 2,463 consecutive patients performed in the same centre between 1995 and 2005 were reviewed. In this group 2,233 cases (representing 91% of the total patients) were followed up 6 months to 8 years (mean 15 months). Patients with insufficient follow-up due to various social problems were excluded. There were 1,238 males and 995 females aged 14 to 78 years (average 47 years). All these patients underwent anterior cervical operations alone, including subaxial cervical trauma (n = 553), cervical spondylosis (n = 1,267), cervical ossified posterior longitudinal ligment (n = 198), cervical vertebral body tumours (n = 158), cervical infections including tuberculosis (n = 46) and cervical kyphosis (n = 11).

The plating crossed one disc level in 514 patients, including C2/3 in 12 cases, C3/4 in 69 cases, C4/5 in 122 cases, C5/6 in 207 cases, C6/7 in 97 cases and C7T1 in 7 cases. It crossed two disc levels in 1,323 cases, including C3~5 in 234 cases, C4~6 in 575 cases, C5~7 in 481 cases and C6~T1 in 33 cases. It crossed three levels in 363 cases, including C3~6 in 211 cases, C4~7 in 138 cases and C5~T1 in 14 cases, as well as four levels in 31 cases, which were all C3~7 levels and five levels in 2 cases.

In total, 607 patients had a discectemy and interbody fusion, 1,375 patients had a corpectemy and strut reconstruction, and 251 patients had a hybrid corpectemy in conjunction with a discectemy. Fusion material included iliac bone autograft and titanium surgical meshes or box cages, which were all filled with bone autograft. Self-locking plates were used in this series, including cervical spine locking plates (CSLP, Synthes, Inc., Switzerland), Orion plates, Zephir plates (Medtronic Sofamor Danek, Inc., Memphis, TN), Codmann plates, Slimloc plates (Johnson & Johnson Co., Depuy Spine, Ltd., Ryhamn, MA), and Reflex plates (Stryker Spine, Inc., France). Patients were advised to use a Philadelphia collar after surgery for 3 to 4 weeks.

Routine anteriorposterior view and lateral view radiographs were taken the day after surgery and flexion-extension lateral view radiographs were added at 6, 12, and 24 weeks after surgery. Bone graft fusion status was observed. Furthermore, the positions of plates and screws were stressed. Any loosening or breaking of the plates and screws and malposition that threatened tracheoesophageal or neurovascular structures were defined as complications of the anterior cervical locking plates.

Results

Anterior cervical locking plate-related complications can be divided into three categories: instant malpositions, biomechanical complications, and tracheoesophageal or neurovascular structural injuries. All kinds of complications were found in the radiographs in this series and are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

The complication types observed in radiographs using anterior cervical locking plates

| Complication types | Cases | Percentage (%) (n = 2,233) |

|---|---|---|

| Plate oblique | 56 | 2.5 |

| Screw in disc | 4 | 0.2 |

| Screw penetrate endplate | 42 | 1.9 |

| Triangle fracture | 19* | 0.9 |

| Screw loosening | 37 | 1.7 |

| Plate loosening | 72 | 3.2 |

| Screw broken | 4 | 0.2 |

| Plate broken | 2 | 0.1 |

| Overlong plate | 14 | 0.6 |

| Total | 239 | 10.7 |

*Eleven cases were included in the “screw penetrates endplate” group

Oblique plating was observed in 56 cases. In this series, oblique plating was defined as the plate axis angled with the cervical midline more than 15° in the anteriorposterior radiographs. Patients had no clinical symptoms except two patients complained of radiculopathy and neck pain. One patient had to have the plate replaced after 2 weeks of ineffective NSAIDs (non-steroid anti-inflammatory drugs) treatment. During the revision, one screw on the left cranial corner was found not to be in the solid bone mass, but in the soft tissue, possibly penetrating into the intervetebral root canal and stimulating the nerve root. Another patient insisted on using NSAIDs for 3 months and the plate was taken out after bone fusion. The symptoms were relieved in both patients after revision surgery.

Screws were driven into the disc spaces in four cases. All the patients had two screws driven into the disc spaces, respectively, with two in C6/7, one in C3/4, and one in C7T1 (Fig. 1). They were treated with a Philadelphia collar and watched for several weeks. Plates loosened at the corresponding end inevitably due to the malpositioning of two screws 1 to 2 months postoperation. All four patients required replacement of the plate. They progressed to bony fusion without any other problems.

Fig. 1.

A lateral view radiograph 6 weeks after surgery shows the two caudal screws in the C7T1 disc space by mistake. The plate was replaced anchored in the bony mass

In 42 cases 76 screws penetrated the end plates and the screw tips went into the intervertebral discs. There was no harm to the discs in the follow-up, which at its longest was up to 4 years, but 11 cases had a triangular bony fracture between the caudal screws and the caudal discs (Fig. 2). Besides that, another eight cases had a triangle fracture with screw tips close to the caudal endplates, but not penetrating them. All the fractures occurred at the caudal end. Cranial end fractures were not found, although some screws penetrated or were close to the cranial endplates. These phenomena always happened between 1 to 6 months after the surgery. Among the 19 cases of fracture, 8 plates were found to pull out 2 mm near the fractures without clinical symptoms. Supplemental longer term fixation using a Philadelphia collar was performed in all cases until bone fusion was achieved and no progression was found.

Fig. 2.

A lateral view radiograph 10 weeks after surgery shows the caudal two screws penetrating the C6 endplate and producing a triangle fracture. The fracture was fused in this position by using a Philadelphia collar

Screws partially pulled out in 37 cases with 41 screws. Among these, 37 screws were in the CSLP and the other 4 were Orion screws fixed to the bone graft without locking to the plate. Eighteen CSLP screws and two Orion screws loosened within 3 months of surgery, and the other screws partially pulled out 6 to 24 months later after bone union. Most screws (36/41) loosened in the range of 2 mm to 5 mm. Longer immobilisation in a Philadelphia collar and close observation were continued until bone fusion 3 months later, and no more progression was found. Five screws pulled out more than 5 mm. Among these five cases an oesophageal perforation occured in three cases at 14 days, 18 days and 31 days after surgery, respectively. One healed 1 month later after tube feeding, wound drainage and parenteral antibiotics while leaving the screw alone. One had a further screw taken out after oesophageal perforation healed. One patient with C5 fracture and total paralysis died of pulmonary infection before the oesophageal perforation closed. The other two patients had had the loosened screw removed before oesophageal perforation occurred.

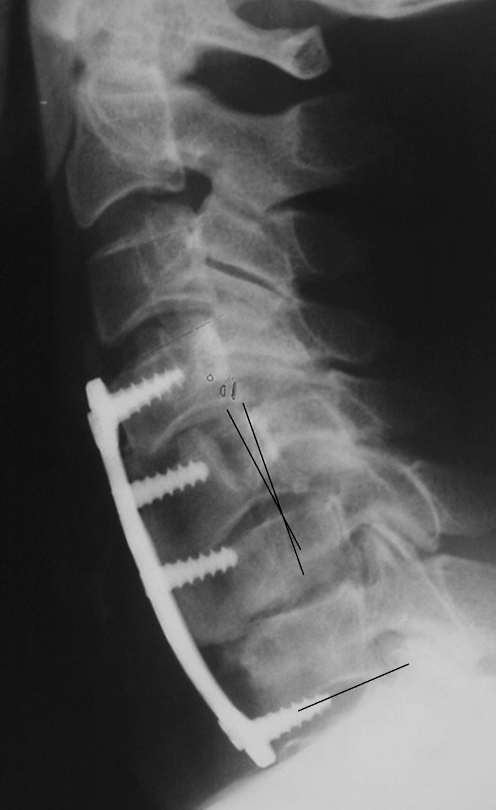

Plate loosening occurred in 72 cases (Fig. 3). All the loosened plates were found between 1 and 12 months, and concomitant non-unions were found in 45 cases, which were mostly multilevel fusions (39/45). In 64 patients loosening was less than 5 mm, in which 52 loosened at one end, mostly the caudal end. All the non-unions were managed by anterior revision surgery using iliac bone autograft and a new plate. The remaining patients were observed for 2 years and no more progressions were found. Another eight cases had loosening more than 5 mm. They received a reoperation to replace the plate and repair the non-union. Among these, three patients had dysphagia, five with no clinical symptoms except some psychological fear.

Fig. 3.

A lateral view radiograph 3 months after surgery shows a plate loosened from the vertebral body and the surgical titanium mesh becoming displaced. A revision surgery was performed to reconstruct the anterior column

A broken screw in four cases and broken plate in two cases were discovered (Fig. 4). All the cases were found at after more than 1 year, the longest being 3 years. Two broken plates were associated with non-union. Non-union was repaired from the anterior approach and a new plate was reapplied. They achieved solid bone fusion 6 months later. One patient with two broken screws complained of dysphagia and neck pain and then the plate was removed. Other patients had no symptoms and no evidence of progression, so no surgical intervention was performed.

Fig. 4.

A lateral view radiograph 3 years after surgery shows two broken screws, although the bone fusion was already achieved. The hardware was preserved

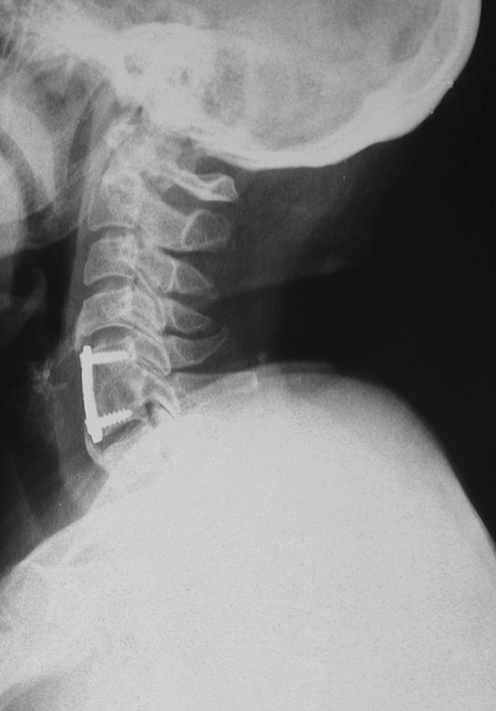

The length of the plating was too long to affect the adjacent spaces in 14 cases. There were 13 semi-constrained platings and one constrained plating. The plating impinged on the disc spaces and promoted degeneration. Osteophytes were found in the adjacent discs after 6 months to 2 years (Fig. 5). Revisions had been done from the anterior to fuse the adjacent levels.

Fig. 5.

A lateral view radiograph 2 years after surgery shows the overlong plate impinged on the adjacent disc space and osteophytes appeared. This patient had a further operation to fuse the adjacent levels

There was no vertebral artery injury, no spinal cord injury or cranial spinal fluid leakage found in this group.

Discussion

Morcher first reported the use of the locking plate in the cervical spine in 1986. After that, complications of plating, especially loosening of the screws and the plates, decreased markedly [10]. Although this technique had become more and more sophisticated, the complication rate continued at a certain level because of the diversity of the surgeons’ experience, indications choice and the understanding of internal fixators.

In the literature the complications of the anterior cervical plate are limited to loosening or breaking of the hardware and tracheoesophageal or neurovascular structural injuries. Other kinds of complications that may lead to clinical symptoms are ignored, and the focus is mainly on unconstrained plates. Furthermore, there are no reports based on a large sample size. In our series of study, more of the kinds of complications encountered with cervical anterior locking plates are discussed. The total complication rate was 10.7% in 2,233 cases.

Instant malpositions

Oblique plating was not rare. This kind of complication was mainly imputed to insufficient exposure and overlooking X-ray conformation during surgery. The main reason was not being able to distinguish the border of the longus colli muscle due to poor exposure. The plate initially used in this series was CSLP, which was designed according to white Caucasian anatomical parameters. So the plating size was not suitable for Asians, whose stature is relatively small. The new generation, which was slimmer, was helpful in decreasing the chance of hiding the longus colli muscle during surgery. Being excessively oblique may lead to screws irritating the nerve root or the vertebral artery. If the patients had no clinical symptom, they were just observed closely. In this series there was no vertebral artery injury, but two patients had radiculopathy. NSIADs were the preferred treatment for neck or arm pain. If not effective, the next step was adjusting the plate or removing the plate after bone fusion. The symptoms can be relieved.

Screws driven into disc spaces mainly occured at the caudal end of the plating, especially at the lower segment or cervical-thoracic junction, such as C6/7 or C7T1. In some obese patients, the neck was short, exposing the cervical-thoracic junction was difficult, and driving the caudal screws in at a correct angle was even more difficult. Furthermore, the shoulder always shaded the caudal segment in the X-ray view during surgery. So surgeons sometimes could not judge whether the caudal screws were located in an appropriate position. The disc material could not hold the screws, leading to loosening and the necessity for replacements. In this series, all four cases happened at the early phase of the learning curve. Good training and careful operation were the best ways to prevent the “floating plate”.

Screws tips penetrating into the disc spaces did not harm to the cervical biomechanical stability and there was no evidence of promotion of disc degeneration in the follow-up. But there was a high risk of vertebral body fracture. This has not been mentioned in the literature before. The fractured fragment was triangular in the lateral view radiographs, for which the three borders were the anterior body wall, caudal endplate and the screw. Most of these fractures appeared at the caudal ends. This phenomenon may be caused by the stress focused on the interface of the screw and the bone mass in the extension position. The screw cut the bone and made it fracture. Furthermore, a triangle fracture occurred in eight other patients, although the screws did not penetrate the end plate. Reviewing the lateral view radiographs, a rule could be found. The screws were excessively close to the end plate and made the surface of the triangle smaller than usual facilitating a fracture of the triangle under high stress in the extension position. An important rule is to keep the screw tip more than 2 mm away from the end plate and keep the screw axis at a smaller angle to the end plate. All the fractures happened between 1 and 6 months after surgery. Prolonged external support up to 3 months till bone fusion can avoid further screw loosening. All the fractures eventually heal and have no serious effect on the cervical biomechanical stability.

Biomechanical complications

Screw and plate loosening was one of the most dangerous complications in cervical anterior plating fixation. A single screw pull out was relatively rare after using the anterior locking plate. In this group, four loosened screws were fixed to the grafting bone without locking to the plate. Other screws were all CSLP screws, for which the locking system was complicated and the expand bolt was easily damaged when surgeons were not familiar with it or could not drive the screws in at the correct 12° angle during surgery. Other anterior plating used in this series had a handy locking design and when adopted the single screw pull out almost disappeared. The loosened screw endangered the oesophagus. Oesophageal perforation after anterior cervical surgery is an uncommon or rarely reported complication. Yee [19] described a case of oesophageal perforation where a loosened screw migrated through the gastrointestinal tract without serious morbidity. The screw was driven into the disc space by mistake. Pompili [13] described a similar case. Orlando [11] reported five cases, and Hanci [8] reported three cases. They recommend that wound drainage and parenteral antibiotics may be an appropriate alternative. In our experience, if the screws loosened less than 2 mm, the patients should be observed closely for evidence of progression toward instability or risk to anatomical structures. Lowery [10] considered that minimally loosened hardware, if not prominent, posed no progressive risks to neighbouring anatomical structures. He reported that during reexploration of hardware, it was noted that there was extensive soft tissue envelopment of the metallic implant. But if the screw loosened more than 5 mm, removing it was an advisable option. In our series, three of five cases ultimately engendered oesophageal perforations. Faced with oesophageal perforation, tube feeding, wound drainage and parenteral antibiotics were effective methods of treatment.

Plate loosening was not rare in cervical surgery. There were several reasons: osteoporosis, multilevel fixation, non-union or pseudarthrosis. Grubb [7] believed non-union and pseudarthrosis would ultimately produce plate loosening. Sasso [16] reported a 6% failure rate after cervical spine locking plate two-level reconstruction, but a 71% failure rate after three-level reconstruction. He believed the long lever arm of the construction was an important reason. In our series, about two-thirds (45/72) of loosening were combined with non-union and 39/45 were multilevel fixation. Another reason was excessive neck movement, especially over-extension. Most of the plating loosened at the caudal end. One of our trauma patients required intubation after surgery that overextended his neck and then engendered a loosened plate. If the plate pulled out more than 5 mm, it was very difficult for the screws to retain their hold on the bone, and the plate may harm the surrounding structures and lead to nonunion. So taking it out early is advisable. Otherwise, the plating can be preserved under close observation.

Screws and plates broke mainly at the root in peudoarthritis or from metal fatigue. Yen [20] reported two patients undergoing two-level anterior corpectomy/fusion with a fixed anterior plate alone and exhibiting plate fracture in conjunction with pseudoarthrosis. He thought multilevel anterior cervical constructs exhibit a relatively high complication rate warranting a simultaneous posterior fusion. The instrument failure was mainly attributed to pseudoarthrosis. However, improper contouring of the plate causing microstructural damage might have created a weak point and contributed to this unusual hardware failure. In our experience, over movement of the neck was another important reason. The anterior cervical plate acted as a supporting plate and a flexion and tension band as an extension in the biomechanical theory. The stress should focus on the plate and the screws when the above-mentioned factors appear, especially at the caudal end during extension. The strength of the plate was greater than the screws’, so the screw breaking was more common. Broken hardware means a failure of internal fixation and the broken component should be removed early if combined with symptoms.

Overlong plating may impinge on the adjacent levels. In some semi-constrained plating, the plate design allowed some settlement during the fusion process. So the plating became relatively longer and close to the adjacent levels. A plate with proper length should be selected considering the settling of the plate when using a semi-constrained plate. Impingement on the intervertebral disc may promote degeneration of the disc material. In this situation, adjacent level revision was unavoidable.

Cervical anterior locking plate-related complications still maintained a certain level. Good training and careful operation may help to decrease the complication rate. Most hardware complications are not symptomatic and can be treated conservatively. Only a few of them need reoperation immediately.

References

- 1.Aebi M, Mohler J, Zach GA, et al. Indication, surgical technique, and results of 100 surgically-treated fractures and fracture-dislocations of the cervical spine. Clin Orthop. 1986;203:244–257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Böhler J, Gaudernak T. Anterior plate stabilization for fracture-dislocations of the lower cervical spine. J Trauma. 1980;20:203–205. doi: 10.1097/00005373-198003000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown JA, Havel P, Ebraheim N, et al. Cervical stabilization by plate and bone fusion. Spine. 1988;13:236–240. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198803000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Casha S, Fehlings MG. Clinical and radiological evaluation of the Codman semiconstrained load-sharing anterior cervical plate: prospective multicenter trial and independent blinded evaluation of outcome. J Neurosurg. 2003;99(3 Suppl):264–270. doi: 10.3171/spi.2003.99.3.0264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Caspar W, Barbier DD, Klara PM. Anterior cervical fusion and Caspar plate stabilization for cervical trauma. Neurosurgery. 1989;25:491–502. doi: 10.1097/00006123-198910000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gassman J, Seligson D. The anterior cervical plate. Spine. 1983;8:700–707. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198310000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grubb MR, Currter BL, Shih JS. Biomechenical evaluation of anterior cervical spine stabilization. Spine. 1998;23:886–892. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199804150-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hanci M, Toprak M, Sarioglu AC, et al. Oesophageal perforation subsequent to anterior cervical spine screw/plate fixation. Paraplegia. 1995;33:606–609. doi: 10.1038/sc.1995.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kostuik JP, Connolly PJ, Esses SI, et al. Anterior cervical plate fixation with the titanium hollow screw plate system. Spine. 1993;18:1273–1278. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199308000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lowery GL, McDonough RF (1998) The significance of hardware failure in anterior cervical plate fixation. Patients with 2- to 7-year follow-up. Spine 23:181–186; Discussion 186–187 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Orlando ER, Caroli E, Ferrante L. Management of the cervical esophagus and hypofarinx perforations complicating anterior cervical spine surgery. Spine. 2003;28:E290–E295. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200308010-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Paramore CG, Dickman CA, Sonntag VK. Radiographic and clinical follow-up review of Caspar plates in 49 patients. J Neurosurg. 1996;84:957–961. doi: 10.3171/jns.1996.84.6.0957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pompili A, Canitano S, Caroli F, et al. Asymptomatic esophageal perforation caused by late screw migration after anterior cervical plating: report of a case and review of relevant literature. Spine. 2002;27:E499–E502. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200212010-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rechtine GR, Cahill DW, Gruenberg M, et al. The synthes cervical spine locking plate and screw system in anterior cervical fusion. Tech Orthop. 1994;9:86–91. doi: 10.1097/00013611-199400910-00014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ripa DR, Kowall MG, Meyer PR et al (1991) Series of ninety-two traumatic cervical spine injuries stabilized with anterior ASIF plate fusion technique. Spine (16 Suppl):S46-S55 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Sasso RC, Ruggiero RA, Jr, Reilly TM, et al. Early reconstruction failures after multilevel cervical corpectomy. Spine. 2003;28:140–142. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200301150-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tominaga T, Koshu K, MIzoi K, et al. Anterior cervical fixation with the titanium locking screw plate: a preliminary report. Surg Neurol. 1994;42:408–413. doi: 10.1016/0090-3019(94)90347-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vaccaro AR, Abraham D, Cotle J et al (1995) Failure of multilevel anterior unicortical cervical plate instrumentation. Presented at the Cervical Spine Research Society, Santa Fe, New Mexico, November 30

- 19.Yee GKH, Terry AF. Esophageal perforation by an anterior cervical fixation device. Spine. 1993;18:522–527. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199303000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yen CP, Hwang TY, Wang CJ, et al. Fracture of anterior cervical plate implant–report of two cases. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2005;147:665–667. doi: 10.1007/s00701-005-0518-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yue WM, Brodner W, Highland TR. Long–term results after anterior cervical discectomy and fusion with allograft and plating: a 5- to 11-year radiologic and clinical follow-up study. Spine. 2005;30:2138–2144. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000180479.63092.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]