Abstract

The lipid A anchor of Francisella tularensis lipopolysaccharide (LPS) lacks both phosphate groups present in Escherichia coli lipid A. Membranes of Francisella novicida (an environmental strain related to F. tularensis) contain enzymes that dephosphorylate lipid A and its precursors at the 1- and 4′-positions. We now report the cloning and characterization of a membrane-bound phosphatase of F. novicida that selectively dephosphorylates the 1-position. By transferring an F. novicida genomic DNA library into E. coli and selecting for low level polymyxin resistance, we isolated FnlpxE as the structural gene for the 1-phosphatase, an inner membrane enzyme of 239 amino acid residues. Expression of FnlpxE in a heptose-deficient mutant of E. coli caused massive accumulation of a previously uncharacterized LPS molecule, identified by mass spectrometry as 1-dephospho-Kdo2-lipid A. The predicted periplasmic orientation of the FnLpxE active site suggested that LPS export might be required for 1-dephosphorylation of lipid A. LPS and phospholipid export depend on the activity of MsbA, an essential inner membrane ABC transporter. Expression of FnlpxE in the msbA temperature-sensitive E. coli mutant WD2 resulted in 90% 1-dephosphorylation of lipid A at the permissive temperature (30 °C). However, the 1-phosphate group of newly synthesized lipid A was not cleaved at the nonpermissive temperature (44 °C). Our findings provide the first direct evidence that lipid A 1-dephosphorylation catalyzed by LpxE occurs on the periplasmic surface of the inner membrane.

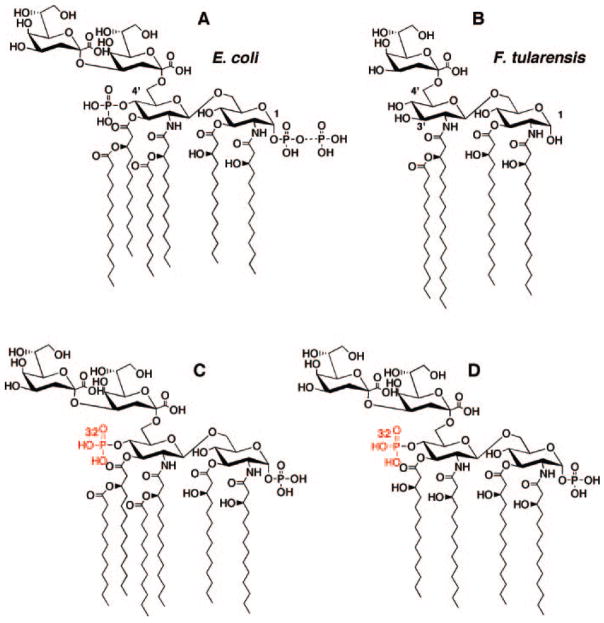

Francisella tularensis is an intracellular Gram-negative bacterium that causes tularemia, a severe and often fatal infection of humans and animals (1). The structure of the lipid A anchor of lipopolysaccharide (LPS)1 in F. tularensis (Fig. 1B) is strikingly different from that of Escherichia coli (Fig. 1A). E. coli lipid A is a hexa-acylated disaccharide of glucosamine, which is phosphorylated at the 1- and 4′-positions (2, 3). It is synthesized by nine constitutive enzymes in the cytoplasm or on the inner surface of the inner membrane (3). Despite having the structural genes for the nine enzymes of the E. coli lipid pathway, F. tularensis synthesizes lipid A lacking phosphate groups (4). Similar phosphate-deficient lipid A structures have been reported in the plant endosymbionts Rhizobium etli and leguminosarum (5–7). In the latter case, specific phosphatases remove the 1- and 4′-phosphate residues late in the pathway (8–10). The biological significance of phosphate-deficient lipid A molecules is uncertain. Mutants lacking the phosphatases have not been reported.

Fig. 1. Structures of the lipid A and Kdo regions of LPS in E. coli and F. tularensis.

Evidence for these structures has been presented elsewhere (3, 4, 36). A, the LPS molecules made by the heptose-deficient E. coli mutant WBB06; B, the Kdo-lipid A region of F. tularensis LPS; C, structure of the Kdo2-[4′-32P]lipid A substrate for the 1-phosphatase; D, structure of the Kdo2-[4′-32P]lipid IVA used to detect both the 4′-phosphatase and the 1-phosphatase.

E. coli lipid A potently activates the TLR-4 receptor of the mammalian innate immune system (11, 12). The phosphate groups are crucial for this bioactivity (13). Lipid A with two phosphate moieties induces a cytokine profile that is lethal to animals (13). Lipid A with one phosphate group is much less toxic, whereas lipid A lacking both phosphates is inactive (13–15). Vaccine development has recently focused on monophosphoryl lipid A analogues, since these induce an altered cytokine profile that retains adjuvant activity without toxicity (15–17). Lipid A without phosphate groups might provide selective advantages for F. tularensis during infections, since a strong innate immune response via TLR-4 would not be induced.

We now describe an inner membrane phosphatase from Francisella novicida, a nonvirulent strain isolated from ground water (18), that selectively removes the 1-phosphate group of lipid A. The Francisella enzyme is distantly related to the R. leguminosarum lipid A 1-phosphatase LpxE (10), but its specific activity in membranes is several orders of magnitude higher. The FnlpxE gene was cloned based on its ability to confer low level polymyxin resistance in E. coli. Approximately 90% of the E. coli lipid A molecules are dephosphorylated at the 1-position in constructs expressing FnlpxE, converting most of the E. coli lipid A from the endotoxin to the adjuvant structure (15). In contrast to lipid A biosynthesis, 1-dephosphorylation of lipid A in living cells requires MsbA, an essential inner membrane ABC transporter and flippase needed for export of LPS and phospholipids to the outer membrane (19). In the temperature-sensitive msbA mutant WD2 (19), FnlpxE is unable to dephosphorylate newly synthesized lipid A in vivo at 44 °C (3, 19). Our results demonstrate for the first time that 1-dephosphorylation of lipid A is an extracytoplasmic event, occurring on the periplasmic surface of the inner membrane.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

Glass-backed 0.25-mm Silica Gel 60 TLC plates were from Merck. Chloroform, ammonium acetate, and sodium acetate were obtained from EM Science, whereas pyridine, methanol, and formic acid were from Mallinckrodt. Trypticase soy broth, yeast extract, and tryptone were purchased from Difco. PCR reagents were purchased from Stratagene, and restriction enzymes were from New England Biolabs. Easy DNA kits were from Invitrogen. Spin Miniprep kits and gel extraction kits were from Qiagen. Shrimp alkaline phosphatase was purchased from U.S. Biochemical Corp. BCA protein assay reagents and tetrabutylammonium phosphate were from Pierce. DEAE-cellulose (DE52) was purchased from Whatman, and octadecyl reverse phase resin was from J.T. Baker Inc.

Bacterial Growth Conditions and Membrane Preparation

F. novicida U112 (18) was grown at 37 °C in TSB-C (3% trypticase soy broth, 0.1% cysteine). E. coli strains were grown at 37 °C or 30 °C in LB broth (1% tryptone, 0.5% yeast extract, and 1% NaCl) with one of the following antibiotics, as appropriate: ampicillin (100 μg/ml), chloramphenicol (30 μg/ml), and kanamycin (30 μg/ml). Table I describes the various bacterial strains used.

Table I.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Genotype or description | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| U112 | Wild-type F. novicida | University of Victoria, Canada |

| W3110A | Wild type E. coli, F−, μ−, aroA::Tn10 | Ref. 53 |

| XL1-Blue | recA1 endA1 gyrA96 thi-1 hsdR17 supE44 relA1 lac | Stratagene |

| XW-1 | XL1-Blue transformed by pACYC184-FnLpxE | This work |

| WD2 | W3110, aroA::Tn10 msbA(A270T) | Ref. 19 |

| WBB06 | E. coli mutant with a deletion of waaC and waaF genes | Ref. 35 |

| Novablue (DE3) | E. coli host strain used for expression | Novagen |

| Plasmids | ||

| pACYC184 | Low copy vector, Tetr Camr | New England Biolabs |

| PXYW-1 | PACYC184 carrying a 2.5-kb genomic DNA containing FnlpxE | This work |

| pET28b | Expression vector, T7lac promoter, Kanr | Novagen |

| pET28b-FnLpxE | pET28b harboring FnlpxE | This work |

| PWSK29 | Low copy vector, Ampr | Ref. 39 |

| PWSK29-FnLpxE | PWSK29 harboring FnlpxE | This work |

The same procedures were used to prepare membranes from either F. novicida U112 or E. coli. Typically, 100-ml cultures were grown to an A600 of 1.0. The cells were harvested by centrifugation at 4 °C. All subsequent steps were carried out at 4 °C or on ice. The cell pellets were washed with 50 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, and resuspended in 10 ml of the same buffer. The cells were disrupted by passage through a French pressure cell at 18,000 p.s.i., and unbroken cells were removed by centrifugation at 13,000 × g for 20 min. The membranes were collected by centrifugation at 100,000 × g for 1 h, washed once by suspension in 10 ml of 50 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, and then resuspended in the same buffer at a protein concentration of about 10 mg/ml. The protein concentrations were determined by the bicinchoninic acid assay with bovine serum albumin as the standard (20).

Assay for the 1-Phosphatase of F. novicida

The 1-phosphatase was assayed in a 10–50-μl reaction mixture at 30 °C, containing 50 mM potassium phosphate, pH 6, 0.1% Triton X-100, 0.1 mg/ml E. coli phospholipids (Avanti), and 10 μM Kdo2-[4′-32P]lipid A (3000–6000 cpm/nmol). The reaction was terminated by spotting 5-μl samples onto a silica TLC plate, which was dried under a cold air stream for 30 min and then developed in the solvent chloroform/methanol/acetic acid/water (25:15:4:4, v/v/v/v). After drying and overnight exposure of the plate to a PhosphorImager screen, product formation was detected and quantified with an Amersham Biosciences Storm PhosphorImager equipped with ImageQuant software.

Expression Cloning of the F. novicida 1-Phosphatase Gene FnlpxE

Recombinant DNA manipulations were carried out according to standard protocols (21, 22). Genomic DNA was isolated from F. novicida U112 using the Easy DNA kit. Typically, 50 μg of genomic DNA was partially digested with 4 units of SauIIIAI in 200 μl at 37 °C for 1 h. The reaction was then incubated at 65 °C for 20 min to inactivate the enzyme. The products were resolved on a 1% agarose gel, and the 2–6-kb DNA fragments were excised and purified using the Gel Extraction kit. Plasmid pACYC184 was opened with BamHI, purified by gel electrophoresis, and treated with shrimp alkaline phosphatase. The 2–6-kb DNA fragments were then ligated into pACYC184 at 16 °C overnight in a 25-μl reaction mixture containing 200 ng of genomic DNA fragments, 200 ng of pACYC184 vector, and 2 units of T4 DNA ligase. E. coli XL1-Blue cells were transformed by electroporation with the ligation mixture, and chloramphenicol-resistant colonies were selected on LB plates. About 15,000 colonies were pooled using a cell scraper and transferred into 250 ml of fresh LB broth, containing 30 μg/ml of chloramphenicol. Cells were grown to saturation, and 10 2-ml 16% glycerol stocks were made and stored at −80 °C.

To select for the 1-phosphatase gene, a glycerol stock of the library was diluted to obtain about 500 colonies per LB plate, containing 30 μg/ml chloramphenicol and 1 μg/ml polymyxin. This amount of polymyxin causes several logs of killing of wild-type E. coli, although much less than the 10 μg/ml polymyxin used to select classical polymyxin-resistant mutants (2, 3). The plates were incubated at 37 °C overnight. The colonies from 15 plates were scraped into 15 separate tubes containing 5 ml of LB broth, 1-ml portions of which were stored as glycerol stocks. Membranes were then prepared from the remaining 4 ml and assayed for 1-phosphatase activity. All of the pools were active, but the level was variable. The glycerol stock from the pool with the highest activity was used to repurify eight polymyxin-resistant colonies by streaking on LB plates, supplemented with 30 μg/ml chloramphenicol and 1 μg/ml polymyxin. Cultures of the repurified colonies were then grown to late log phase and centrifuged. Only two of eight colonies grew under selective conditions in liquid medium. The cell pellets of these two strains were resuspended in 5 ml of 50 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, and disrupted with a French pressure cell. Unbroken cells were removed by centrifugation at 13,000 × g for 20 min. The cell-free extracts of these cultures were assayed for 1-phosphatase activity. Both colonies tested in this manner were positive for 1-phosphatase activity. A representative strain expressing the 1-phosphatase activity was designated XW-1.

The hybrid plasmid pXYW-1 was isolated from XW-1 using the Qiagen Spin Miniprep kit. The DNA insert was sequenced by using the Terminator Cycle system and the ABI Prism 377 instrument at the Duke University DNA Analysis Facility. According to the program ORF Finder (23), the 2.5-kb insert contains three open reading frames. BLASTp search analysis (24) showed that only one of these three open reading frames is a member of the lipid phosphatase family (25). We assumed that this 717-bp DNA fragment would be the FnlpxE gene, encoding the 1-phosphatase in F. novicida.

FnlpxE was amplified by PCR and cloned into the pET28b vector behind the T7lac promoter. The forward PCR primer (5′-CGGATCCATGGTCAAACAGACATTACAAACAAACTTT-3′) was designed with a clamp region, a NcoI restriction site (underlined), and a match to the coding strand starting at the translation initiation site. The reverse primer (5′-CGGATCCTCGAGCTAAATAATCTCTCTATTTCTCATCC-3′) was designed with a clamp region, an XhoI restriction site (underlined), and a match to the anti-coding strand that included the stop codon. The PCR was performed using Pfu polymerase and plasmid pXYW-1 as the template. Amplification was carried out in a 100-μl reaction mixture containing 100 ng of template, 250 ng of primers, and 2 units of Pfu polymerase. The reaction was started at 94 °C for 1 min, followed by 25 cycles of denaturation (30 s at 94 °C), annealing (30 s at 55 °C), and extension (45 s at 72 °C). After the 25th cycle, a 10-min extension time was used. The reaction product was analyzed on a 1% agarose gel. The desired band was excised and gel-purified. The PCR product was then digested using NcoI and XhoI and ligated into the expression vector pET28b that had been similarly digested and treated with shrimp alkaline phosphatase. The ligation mixture was transformed into XL1-Blue cells and screened for positive inserts on LB plates containing 30 μg/ml kanamycin. Plasmid pET28b-FnLpxE was isolated from the positive transformants, and the FnlpxE insert was confirmed by DNA sequencing. The plasmid pET28b-FnLpxE was then transformed into the E. coli expression strain Novablue (DE3). To construct pWSK29-FnLpxE, pET28b-FnLpxE was digested using XbaI and XhoI and ligated into the vector pWSK29 that had been similarly digested and treated with shrimp alkaline phosphatase. The ligation mixture was transformed into XL1-Blue cells, and ampicillin-resistant transformants were selected on LB plates. The plasmid pWSK29-Fn-LpxE was isolated from the positive clones and then transformed into WBB06 to obtain WBB06/pWSK29-FnLpxE. The strains and plasmids constructed in this study are summarized in Table I.

Preparation of Kdo2-lipid A and 1-Dephospho-Kdo2-lipid A

Kdo2-[4′-32P]lipid A (Fig. 1C) was generated from Kdo2-[4′-32P]lipid IVA (Fig. 1D) by acylation with lauroyl-acyl carrier protein and membranes over-expressing LpxL(HtrB) and LpxM(MsbB) (26, 27). The Kdo2-[4′-32P]lipid IVA was prepared from the [4′-32P]lipid IVA with purified E. coli Kdo transferase (KdtA) (28), and [4′-32P]lipid IVA was generated from [γ-32P]ATP and the tetraacyl-disaccharide 1-phosphate precursor using the overexpressed 4′-kinase present in membranes of E. coli BLR(DE3)/pLysS/pJK2 (29). Kdo2-[4′-32P]lipid A was purified by pre-parative TLC (28).

Kdo2-lipid A carrier (purified to remove the 1-diphosphate variant shown in Fig. 1A) was isolated from the E. coli strain WBB06 based on published procedures (30, 31). Briefly, the cells were grown, harvested by centrifugation, and washed with phosphate-buffered saline. The cells were extracted for 1 h at room temperature with a single phase Bligh-Dyer mixture consisting of chloroform/methanol/water (1:2:0.8, v/v/v). Insoluble material was removed by centrifugation, and the supernatant, containing the Kdo2-lipid A, was converted to a two-phase Bligh-Dyer system by the addition of chloroform and dilute HCl to give the mixture chloroform, methanol, 0.1 M HCl (2:2:1.8, v/v/v). A few drops of pyridine were added to neutralize residual HCl in the lower phase, which was dried with a rotary evaporator. The lipids were dissolved in chloroform/methanol/water (2:3:1, v/v/v) and applied to a 2-ml DEAE-cellulose column, prepared as the acetate form in the same solvent (32, 33). The Kdo2-lipid A was eluted in steps with increasing amounts of ammonium acetate. The fractions containing the purified Kdo2-lipid A were pooled and converted to a two-phase Bligh-Dyer system (34). The lower phase was dried under a stream of nitrogen. The final yield of purified Kdo2-lipid A was about 5 mg from 2 liters of late log phase cells. The Kdo2-lipid A was greater than 95% pure as judged by TLC analysis, followed by sulfuric acid charring and by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight (MALDI-TOF) mass spectrometry (data not shown). The Kdo2-lipid A carrier (Fig. 1A) is acylated with a secondary myristate chain at position 3′, where the Kdo2-[4′-32P]lipid A probe (Fig. 1C) is substituted with laurate. This has no effect on the activity of the 1-phosphatase (data not shown).

To obtain 1-mg quantities of 1-dephospho-Kdo2-lipid A from cells, pWSK29-FnLpxE was transformed into WBB06 (35). WBB06/pWSK29-FnLpxE was grown to late log phase, and the 1-dephospho-Kdo2-lipid A was isolated by the same procedure used for Kdo2-lipid A. To further purify the material eluted from DEAE cellulose, the relevant fractions were pooled, dried, and dissolved in a 1:1 mixture of 50% aqueous acetonitrile (solvent A) and 85% aqueous isopropyl alcohol (solvent B), both of which also contained 1 mM tetrabutylammonium phosphate. An octadecyl (C18) reverse phase column (2 ml) was prepared, and the sample was applied. The column was then eluted with 5 column volumes of each of the following A:B mixtures: 1:1, 1:2, 1:3, 1:4, and 1:6, each containing 1 mM tetrabutylammonium phosphate. The 1-dephospho-Kdo2-lipid A eluted in the 1:2 fraction. The peak fractions were pooled, diluted 3-fold into chloroform/methanol/water (2:3:1, v/v/v), and applied to a fresh 2-ml DEAE-cellulose column. The column was washed with 5 volumes of chloroform/methanol/water (2:3:1, v/v/v) and eluted with 10 column volumes of chloroform, methanol, 500 mM aqueous ammonium acetate (2:3:1, v/v/v). The relevant fractions were pooled and converted to a two-phase Bligh-Dyer system. The lower phase was dried to obtain the purified 1-dephospho-Kdo2-lipid A. The final yield was about 2.5 mg from 1 liter of cells. The purity was confirmed by TLC, followed by sulfuric acid charring, and by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry (data not shown).

Isolation of Lipid A Species from 32P-Labeled Cells

Typically, 20 ml of LB broth cultures were labeled with 5 μCi/ml 32 Pi, starting at an initial A600 of 0.02. The 32P-labeled cells were grown, harvested, and washed with phosphate-buffered saline. The pellets were resuspended in 3 ml of a single-phase Bligh-Dyer mixture, incubated at room temperature for 60 min, and centrifuged to remove insoluble debris. For WBB06 and related heptose-deficient strains, the supernatant contains the Kdo2-lipid A and glycerophospholipids. This was converted to a two-phase Bligh-Dyer system by the addition of appropriate amounts of chloroform and water (34). For wild-type strains with a complete core domain, the lipid A is covalently attached to the LPS in the insoluble pellet. To recover the lipid A, the pellet was resuspended in 3 ml of 12.5 mM sodium acetate (pH 4.5) with 1% SDS and heated at 100 °C for 30 min (36, 37). The suspension was converted to a two-phase Bligh-Dyer system by the addition of chloroform and methanol. After thorough mixing, the two phases were separated by centrifugation, and the upper phase was washed once with a fresh pre-equilibrated lower phase. The lower phases were pooled and dried under a stream of nitrogen. The dried lipids were redissolved in chloroform/methanol (4:1, v/v). The 32P-labeled lipid A species were spotted onto a Silica Gel 60 TLC plate (10,000 cpm/lane), which was developed in the solvent chloroform, pyridine, 88% formic acid/water (50:50:16:5, v/v/v/v) or chloroform/methanol/acetic acid/water (25:15:4:4, v/v/v/v), as indicated. After drying, the plates were exposed to a PhosphorImager Screen overnight.

MALDI-TOF Mass Spectrometry

MALDI-TOF mass spectra were acquired using an AXIMA-CFR instrument from Kratos Analytical (Manchester, UK) with a nitrogen laser (337 nm), 20-kV extraction voltage, and time-delayed extraction. The samples were prepared for MALDI-TOF analysis by depositing 0.3 μl of the lipid sample dissolved in chloroform/methanol (4:1, v/v), followed by 0.3 μl of a saturated solution of 6-aza-2-thiothymine in 50% acetonitrile and 10% tribasic ammonium citrate (9:1, v/v) as the matrix. The samples were left to dry at room temperature before the spectra were acquired in both the positive and negative ion linear modes. Each spectrum was the average of 100 laser shots.

RESULTS

Lipid A 1- and 4′-Phosphatase Activities in F. novicida Membranes

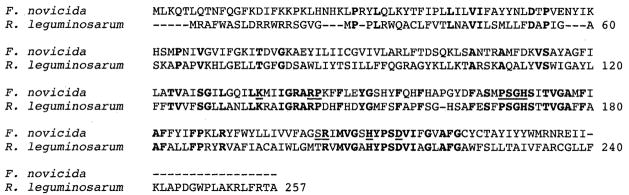

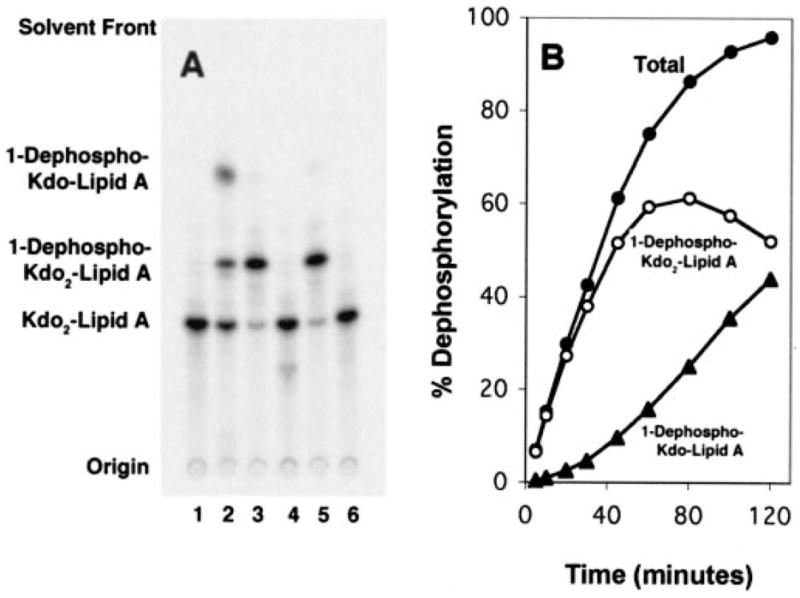

Although the lipid A of F. tularensis lacks phosphate groups, and its LPS contains only one Kdo residue (Fig. 1B) (4), orthologs of the nine E. coli enzymes that synthesize E. coli Kdo2-lipid A (Fig. 1A) (3) are present in F. tularensis (see, on the World Wide Web, artedi.ebc.uu.se/Projects/Francisella/). We therefore searched for lipid A 1- and 4′-phosphatase activities that might account for the F. tularensis structure. F. novicida U112, an environmental isolate related to F. tularensis, was used to prepare membranes. Kdo2-[4′-32P]lipid IVA (Fig. 1D) was initially employed as the probe substrate. As shown in Fig. 2, lanes 2–5, F. novicida membranes catalyzed the rapid release of the 4′-phosphate group from Kdo2-[4′-32P]lipid IVA, as judged by the formation of 32Pi. In addition, a more rapidly migrating lipid was formed (Fig. 2, lanes 2–5). This material was tentatively identified as 1-dephospho-Kdo2-[4′-32P]lipid IVA, given its migration with a standard generated by membranes of E. coli Novablue expressing the R. leguminosarum 1-phosphatase, LpxE (Fig. 2, lanes 6 and 7). Neither the 1- nor the 4′-phosphatase activities were present in membranes of E. coli harboring the vector control (Fig. 3A, lane 6).

Fig. 2. Detection of lipid A 1-phosphatase and 4′-phosphatase activities in F. novicida U112 membranes.

Membranes (0.5 mg/ml) of F. novicida U112 (lanes 2–5) or E. coli Novablue/pLpxE (10), which expresses the 1-phosphatase of R. leguminosarum (lanes 6 and 7), were assayed for the indicated times at 30 °C with 5 μMKdo2-[4′-32P]lipid IVA (20,000 cpm/nmol) as the substrate (structure in Fig. 1D). The products were separated by TLC in the solvent chloroform, pyridine, 88% formic acid/water (30:70:16:10, v/v/v/v) and were detected with a PhosphorImager. The RF of the 1-dephospho-Kdo2-[4′-32P]lipid IVA was confirmed by comparison with the product generated with the previously characterized LpxE 1-phosphatase of R. leguminosarum, expressed in E. coli Novablue (lanes 6 and 7).

Fig. 3. Lipid A 1-phosphatase and Kdo trimming activities in membranes of F. novicida.

A, membranes of different strains were assayed for 1-phosphatase activity with substrate Kdo2-[4′-32P]lipid A as the substrate. Lane 1, no enzyme; lane 2, F. novicida U112; lane 3, XW1/pXYW-1; lane 4, XL1-Blue/pACYC184; lane 5, Novablue/pET28b-FnLpxE; lane 6, Novablue/pET28b. The reaction was performed at 30 °C for 30 min with 0.2 mg/ml membranes. The TLC solvent was CHCl3/methanol/acetic acid/water (25:25:4:4, v/v/v/v). B, the lag in the formation of 1-dephospho-Kdo lipid A by F. novicida membranes demonstrates that the Kdo-trimming enzyme prefers a substrate lacking the 1-phosphate group. The 1-dephospho-Kdo lipid A was identified by mass spectrometry based on its [M − H]− at m/z 1938.9 and by its conversion to 1-dephospho-Kdo2 lipid A in the presence of E. coli KdtA (65).

An Alternative Assay for the 1-Phosphatase and Evidence for a Kdo Trimming Activity

Robust 1-phosphatase activity was detected after 30 min at 30 °C with only 0.2 mg/ml F. novicida membranes when hexa-acylated Kdo2-[4′-32P]lipid A (Fig. 1C) was used as the substrate (Fig. 3A, lane 2 versus lanes 4 and 6). An additional product, migrating more rapidly than 1-dephospho-Kdo2-[4′-32P]lipid A (Fig. 3A, lane 2), was also observed. This material was identified as the single Kdo residue containing 1-dephospho-Kdo-[4′-32P]lipid A by mass spectrometry and enzymatic treatments, as described in the legend to Fig. 3. Its appearance was dependent upon the formation of 1-dephospho-Kdo2-[4′-32P]lipid A (Fig. 3B), suggesting that the Kdo-trimming enzyme of F. novicida prefers a substrate lacking the 1-phosphate group.

The 4′-phosphatase is greatly suppressed when hexa-acylated Kdo2-[4′-32P]lipid A (Fig. 1C) is employed (Fig. 3A, lane 2, versus Fig. 2, lanes 2–5). The 4′-phosphatase appears to be selective for lipid A molecules containing four or five fatty acyl chains. Accordingly, only hexa-acylated Kdo2-[4′-32P]lipid A was used in subsequent assays of the 1-phosphatase, since interference by the 4′-phosphatase was eliminated.

Selection for the F. novicida 1-Phosphatase Gene Based on Low Level Polymyxin Resistance

A genomic DNA library of F. novicida U112 was constructed in E. coli XL1-Blue. The library was grown on LB plates containing 30 μg/ml chloramphenicol and 1 μg/ml polymyxin. Wild-type E. coli growth is inhibited by 1 μg/ml polymyxin, causing several logs of cell killing. Removal of the 1-phosphate group reduces the net negative charge of lipid A (10), decreasing its affinity for polymyxin. Therefore, a clone expressing the F. novicida 1-phosphatase might be somewhat resistant to polymyxin. Membranes of strain XW-1, a transformant of E. coli XL1-Blue harboring plasmid pXYW-1, which was selected as polymyxin-resistant at 1 μg/ml, showed strong lipid A 1-phosphatase activity (Fig. 3A, lane 3). The 1-phosphatase was absent in the vector control (Fig. 3A, lane 4), as in all strains of wild-type E. coli.

The 2.5-kb F. novicida DNA insert in plasmid pXYW-1 was sequenced and found to contain a 717-bp open reading frame homologous to members of the lipid phosphate phosphatase superfamily (25). This gene was amplified by PCR, ligated into the expression vector pET28b, and transformed into E. coli Novablue cells. Membranes from Novablue/pET28b-FnLpxE were prepared and assayed with Kdo2-[4′-32P]lipid A for 1-phosphatase activity. Massive expression of 1-phosphatase activity was observed in membranes of Novablue/pET28b-Fn-LpxE (Fig. 3A, lane 5) but not in the vector control Novablue/pET28b (Fig. 3A, lane 6). The Kdo trimming activity present in F. novicida membranes (Fig. 3A, lane 2) was not present with the recombinant lipid A 1-phosphatase expressed in E. coli (Fig. 3A, lanes 3 and 5), indicating that it is probably catalyzed by a different enzyme.

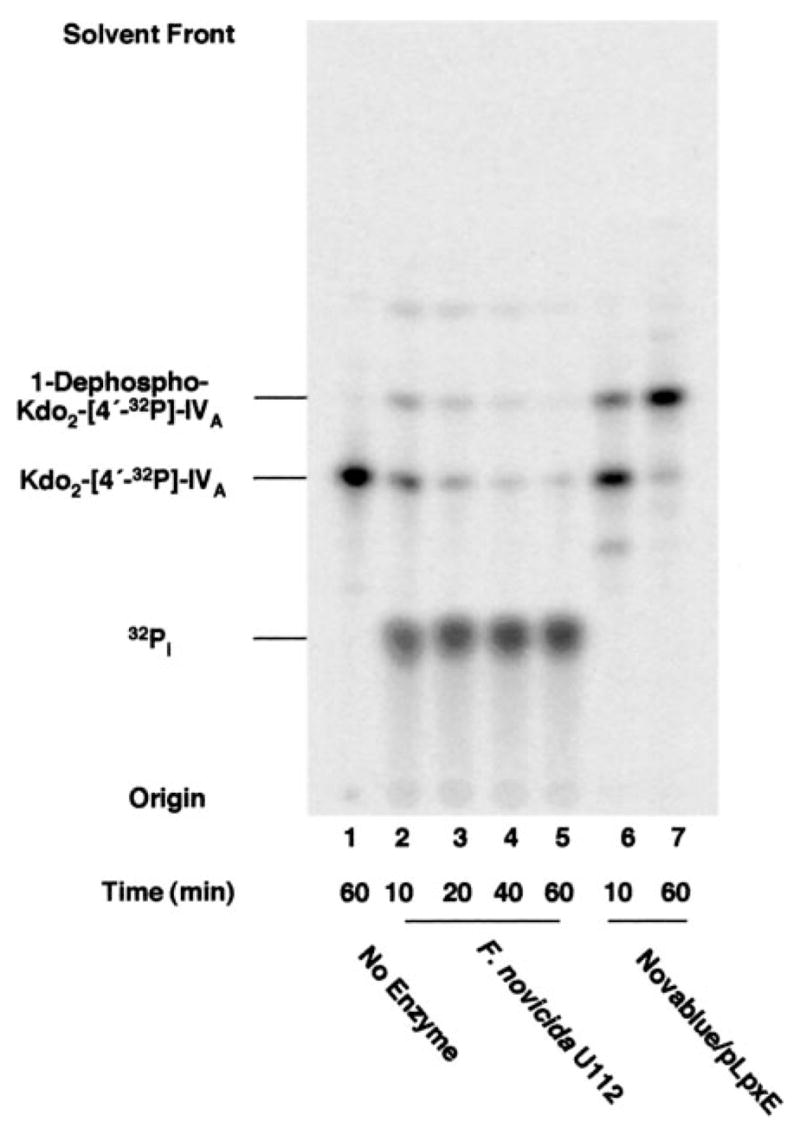

The gene encoding the F. novicida 1-phosphatase was designated FnlpxE. The FnLpxE protein (Fig. 4) consists of 239 amino acid residues and is related to LpxE of R. leguminosarum with an E value of ~6 × 10−20 in a two-sequence comparison without low complexity filtering (10). Both LpxEs possess six putative transmembrane helices and the conserved lipid phosphatase motifs KX6RP--------PSGH--------SRX5HX3D (25), which are predicted to face the outer surface of the inner membrane in both proteins (38). The FnLpxE 1-phosphatase sequence has been deposited under GenBank™ accession number AY713119.

Fig. 4. Alignment of LpxE sequences from F. novicida and R. leguminosarum.

The conserved residues are in boldface type. The predicted FnLpxE protein contains all three motifs of the lipid phosphatase superfamily (25), which are underlined. The proteins are 44% identical and 57% similar over 122 residues with one gap. The E value in a two-sequence comparison is 6 × 10–20. The F. novicida and F. tularensis proteins (not shown) are 98% identical over 239 amino acid residues.

Optimizing the Expression of FnlpxE in E. coli

The formation of 1-dephosphorylated lipid A was linear with respect to time and protein concentration in all membrane preparations. However, the specific activity of the 1-phosphatase under optimized conditions was orders of magnitude higher in F. novicida membranes (27.4 nmol/min/mg) than in R. leguminosarum membranes (0.014 nmol/min/mg) (10). Recombinant Francisella LpxE was likewise more active than recombinant Rhizobium LpxE. When FnLpxE was expressed behind the T7 promoter on pET28b-FnLpxE in E. coli Novablue (Fig. 3A, lane5), the 1-phosphatase specific activity in membranes was 6.4 nmol/min/mg. Production of active FnLpxE in E. coli was improved further when the FnlpxE gene was expressed behind the lac promoter on pWSK29 (39). The 1-phosphatase specific activity of XL1-Blue/pWSK29-FnLpxE membranes was 62.3 nmol/min/mg. The true specific activities of the two phosphatases will have to be reevaluated with homogeneous enzyme preparations.

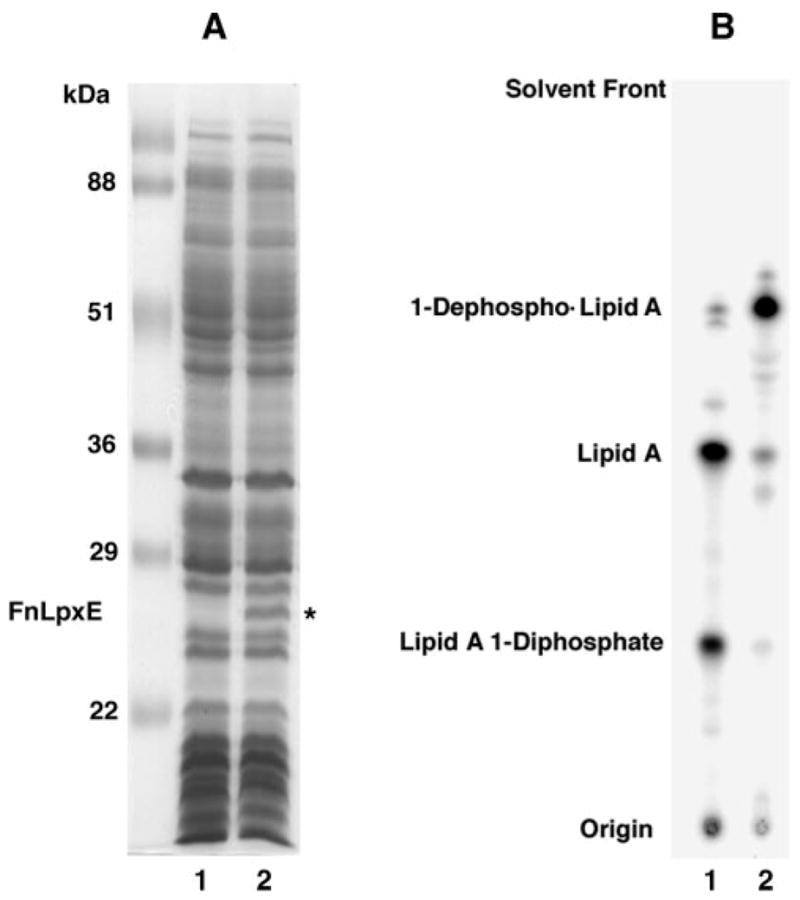

Membrane proteins from XL1-Blue/pWSK29-FnLpxE were separated by SDS-PAGE, followed by staining with Coomassie Blue (Fig. 5A). When compared with vector control, an additional protein was observed at 27.5 kDa, the size expected for FnLpxE. To determine whether FnLpxE functions to dephosphorylate lipid A at its 1-position when expressed in living cells of E. coli, strains XL1-Blue/pWSK29 and XL1-Blue/pWSK29-FnLpxE were labeled for several generations with 32Pi. The 32P-labeled lipid A species were isolated and separated by TLC. Lipid A and its 1-diphosphate derivative (Fig. 1A) were recovered from the vector XL1-Blue/pWSK29 (Fig. 5B, lane 1), whereas a major new lipid A species accumulated in XL1-Blue/pWSK29-FnLpxE (Fig. 5B, lane 2). The rapid migration of this substance is consistent with 1-dephosphorylation of lipid A in wild-type E. coli cells expressing recombinant FnLpxE. The levels of both lipid A and its diphosphate derivative (Fig. 1A) are greatly reduced (Fig. 5B, lane 2). The transfer of pWSK29-FnLpxE into Salmonella typhimurium also resulted in extensive 1-dephosphorylation of endogenous lipid A (data not shown).

Fig. 5. Lipid A 1-dephosphorylation in E. coli XL1-Blue expressing FnLpxE.

A, SDS-PAGE analysis of 25-μg protein samples of the indicated membranes: XL1-Blue/pWSK29 (lane 1); XL1-Blue/pWSK29-FnLpxE (lane 2). The molecular mass of FnLpxE is about 27.5 kDa. B, cells expressing FnLpxE dephosphorylate over 90% of their endogenous lipid A, as judged by steady state 32P-labeling and TLC of the lipid A species in the solvent CHCl3, pyridine, 88% formic acid/water (50:50:16:5, v/v/v/v). Lipids were detected with a PhosphorImager. Lane 1, XL1-Blue/pWSK29; lane 2, XL1-Blue/pWSK29-FnLpxE.

Mass Spectrometry of LPS from Heptose-deficient E. coli Expressing FnLpxE

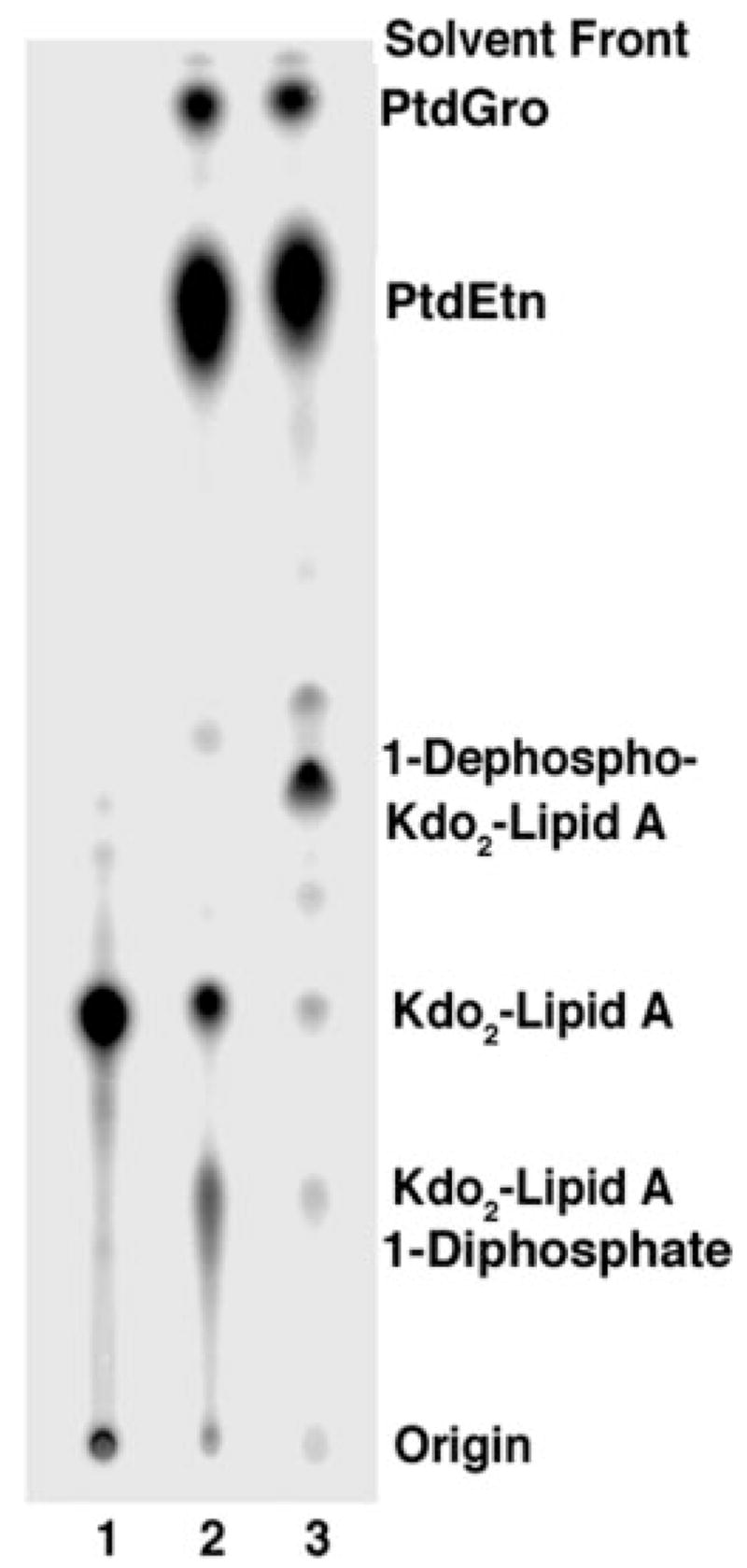

To show conclusively that FnLpxE is functional and absolutely specific for the 1-position of lipid A in living cells of E. coli, the 1-phosphatase-expressing pWSK29-FnLpxE plasmid was transformed into E. coli WBB06 (35), a heptose-deficient mutant with a deletion spanning the waaC and waaF genes. When grown in the absence of calcium ions, WBB06 synthesizes a truncated LPS consisting mainly of Kdo2-lipid A and some of the 1-diphosphate variant (Fig. 1A) (30). However, it cannot add any additional core sugars. WBB06/pWSK29-FnLpxE and the vector control strain WBB06/pWSK29 were grown in parallel for several generations in the presence of 32Pi. LPS and phospholipids were extracted directly with chloroform/methanol without the need for a hydrolysis step, resolved by TLC, and detected with a PhosphorImager. Both Kdo2-lipid A and the Kdo2-lipid A 1-diphosphate (Fig. 1A) were present in WBB06/pWSK29 (Fig. 6, lane 2) (30). The levels of both compounds were greatly reduced in WBB06/pWSK29-FnLpxE (Fig. 6, lane 3) and replaced by a more rapidly migrating substance, presumed to be 1-dephospho-Kdo2-lipid A (Fig. 6, lane 3). Phosphatidylglycerol and phosphatidylethanolamine were present at normal levels (Fig. 6, lanes 2 and 3), suggesting that FnLpxE does not hydrolyze phospholipid precursors, such as phosphatidic acid (40), which would inhibit phospholipid synthesis. The selectivity of FnLpxE for lipid A was confirmed independently by demonstrating that it does not catalyze significant phosphatidic acid or phosphatidylglycerophosphate dephosphorylation in vitro compared with vector controls (data not shown). Furthermore, it does not dephosphorylate the 4′-position of tetra-acylated lipid A precursors.

Fig. 6. Lipid A 1-dephosphorylation by FnLpxE in a heptose-deficient mutant.

The lipids were labeled uniformly with 32 and Pi extracted with a Bligh-Dyer mixture. The crude 32P-labeled lipids were separated by TLC in chloroform/methanol/acetic acid/water (25:15:4:4, v/v/v/v) and detected with a PhosphorImager. Lane 1, a Kdo2-[4′-32P]lipid A standard; lane 2, lipids from WBB06; lane 3, lipids from WBB06/pWSK29-FnLpxE.

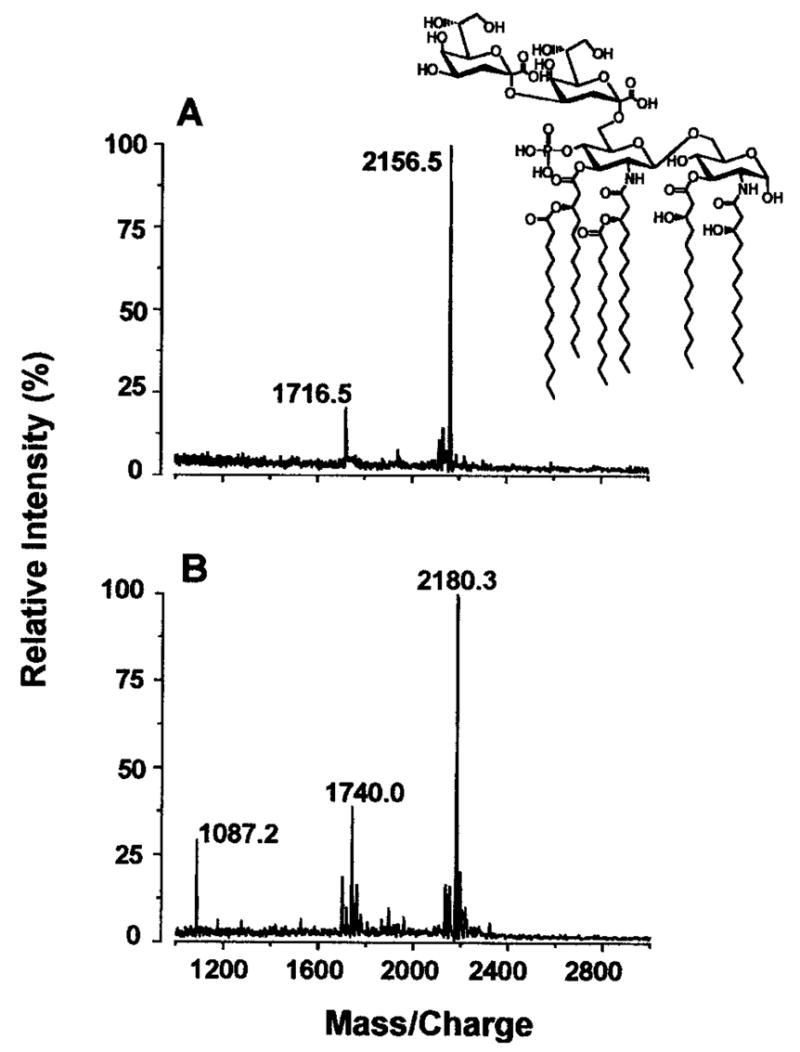

The presumed 1-dephospho-Kdo2-lipid A in WBB06/pWSK29-FnLpxE was isolated in 1-mg amounts and analyzed by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry. The negative mode (Fig. 7A) demonstrates a major peak at m/z 2156.5, which is consistent with [M − H]− for 1-dephospho-Kdo2-lipid A (Fig. 7A, structure inset). The peak at m/z 1716.5 probably arises by loss of the Kdo disaccharide, which is labile under these conditions. In the positive mode (Fig. 7B), the peak at m/z 2180.3 is interpreted as [M + Na]+ for 1-dephospho-Kdo2-lipid A, whereas the peak at m/z 1740.0 arises by loss of the Kdo disaccharide. The peak at m/z 1087.2 is the B1+ ion (41) arising from the distal glucosamine unit, which is the same as the B1 ion seen in the positive ion spectrum of Kdo2-lipid A or lipid A. This finding demonstrates unequivocally that the distal glucosamine unit is intact in the novel LPS derivative that accumulates in WBB06/pWSK29-FnLpxE. FnLpxE dephosphorylates only the 1-position of lipid A in vivo and not the 4′-position. Additional validation for the structure shown in Fig. 7A was obtained by examining the 31P and 1H NMR spectra (42) of the 1-dephospho-Kdo2-lipid A obtained from WBB06/pWSK29-Fn-LpxE (data not shown).

Fig. 7. MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry of purified 1-dephos-pho-Kdo2-lipid A.

The spectra were acquired in the negative mode (A) and the positive mode (B ). The molecular weight of 1-dephospho-Kdo2-lipid A is 2157.4.

FnLpxE-catalyzed 1-Dephosphorylation of Lipid A Is MsbA-dependent

FnLpxE is predicted to have six transmembrane helices with its conserved lipid phosphatase motifs facing the periplasmic surface of the inner membrane (38). Because Kdo2-lipid A is synthesized on the cytosolic face of the inner membrane, it would need to be flipped to the periplasmic surface to be 1-dephosphorylated. MsbA is an essential ABC transporter and LPS flippase in E. coli (19). Therefore, blocking MsbA in living cells might prevent 1-dephosphorylation of newly synthesized lipid A. We previously demonstrated that a temperature-sensitive point mutation in msbA can lead to rapid cessation of phospholipid and lipid A export (19). Since there is no cessation of phospholipid and lipid A biosynthesis when MsbA is inactivated, newly made lipids accumulate in the inner membrane (19), presumably on its inner surface. MsbA is a homodimer that is closely related to the mammalian Mdr proteins (43, 44).

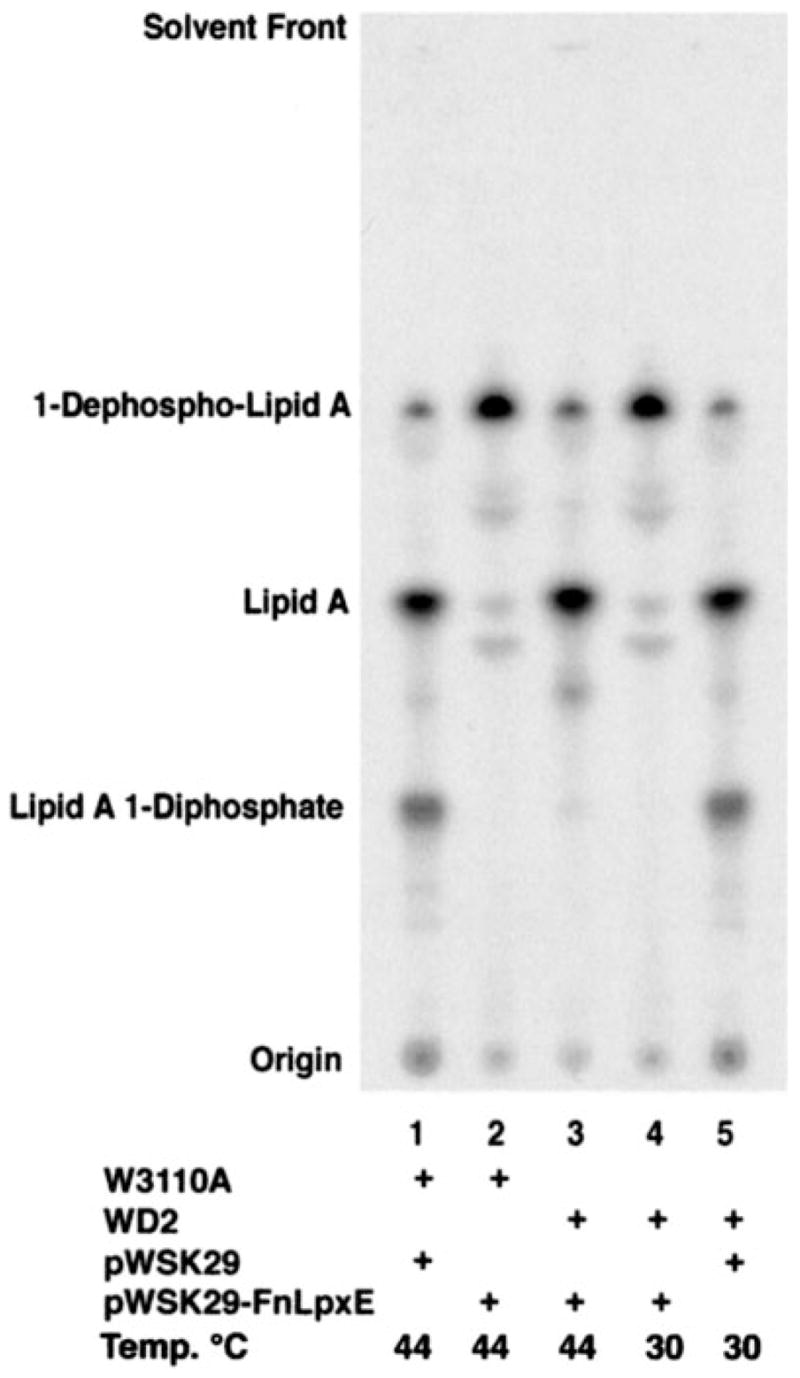

Accordingly, pWSK29-FnLpxE was transformed into WD2, a temperature-sensitive E. coli mutant with an A270T substitution in the fifth transmembrane helix of MsbA (19). MsbA is inactivated in WD2 by shifting the cells from 30 to 44 °C for 30 min during midlog phase (19). To study the effects of MsbA inactivation on the function of the 1-phosphatase in vivo, W3110A/pWSK29, W3110A/pWSK29-FnLpxE, WD2/pWSK29-FnLpxE, and WD2/pWSK29 were grown at 30 °C until A600 reached 0.6–0.8. After 30 min at 44 °C, the cells were labeled with 4 μCi/ml 32Pi for 20 min. The 32P-labeled lipid A species were extracted after hydrolysis at pH 4.5 to cleave off the Kdo and core sugars (36, 37) and then separated by TLC. At 44 °C, the control strain W3110A/pWSK29 synthesized the normal E. coli lipid A and its 1-diphosphate derivative (Fig. 8, lane 1), whereas W3110A/pWSK29-FnLpxE synthesized mainly the 1-dephosphorylated species (Fig. 8, lane 2). The same results were obtained at 30 °C (not shown). When MsbA was inactivated at 44 °C in WD2/pWSK29-FnLpxE, newly synthesized lipid A was not 1-dephosphorylated (Fig. 8, lane 3), demonstrating that FnLpxE is MsbA-dependent and confirming the periplasmic orientation of the 1-phosphatase active site.

Fig. 8. Lipid A 1-dephosphorylation by FnLpxE is MsbA-dependent.

FnLpxE expressed in the temperature-sensitive MsbA mutant WD2 (19) cannot dephosphorylate newly synthesized lipid A when MsbA is inactivated at 44 °C for 30 min. Lane 1, W3110A/pWSK29, 44 °C; lane 2, W3110A/pWSK29-FnLpxE, 44 °C; lane 3, WD2/pWSK29-FnLpxE, 44 °C; lane 4, WD2/pWSK29-FnLpxE, 30 °C; lane 5, WD2/pWSK29, 30 °C. The TLC of the lipid A species was carried out with the solvent CHCl3, pyridine, 88% formic acid/water (50:50:16:5, v/v/v/v). The small amount of 1-dephosphorylated lipid A present in lanes 1, 3, and 5 is not present in living cells. It is an artifact that arises due to the partial loss of the anomeric phosphate during pH 4.5 hydrolysis at 100 °C of LPS, which releases the lipid A from LPS by cleaving the Kdo-lipid A linkage.

At the permissive temperature of 30 °C, lipid A was 1-dephosphorylated by FnLpxE in WD2 (Fig. 8, lane 4), as in W3110A/pWSK29-FnLpxE. When the vector control strain WD2/pWSK29 was grown at 30 °C, both lipid A and the 1-diphosphate variant were present in normal amounts (Fig. 8, lane 5), as in W3110A/pWSK29. However, the lipid A 1-diphosphate did not accumulate together with lipid A in WD2/pWSK29-FnLpxE when MsbA was inactivated at 44 °C (Fig. 8, lane 3). This is consistent with previous data demonstrating that the lipid A 1-diphosphate species is produced in the periplasm or outer membrane (45). When MsbA is functioning properly, FnlpxE may prevent the formation of the lipid A 1-diphosphate by competing for newly synthesized lipid A molecules that appear on the periplasmic side of the inner membrane. Alternatively, FnLpxE might dephosphorylate the lipid A 1-diphosphate directly.

DISCUSSION

The biosynthesis of the lipid A and core domains of LPS in Gram-negative bacteria begins in the cytoplasm and on the inner surface of the inner membrane (2, 3). Additional enzymes located on the outer surface of the inner membrane and in the outer membrane complete the assembly of LPS. For example, when the O-antigen is present, it is attached to the LPS-core on the outer surface of the inner membrane (2, 3, 46). In the outer membrane, PagP (47, 48), which is induced by growth at low divalent cation concentrations (49, 50), adds a seventh acyl chain to lipid A in a transacylation reaction that requires a phospholipid as the donor substrate (47, 51). The present study demonstrates for the first time that lipid A 1-dephosphorylation, when it occurs, takes place on the outer surface of the inner membrane.

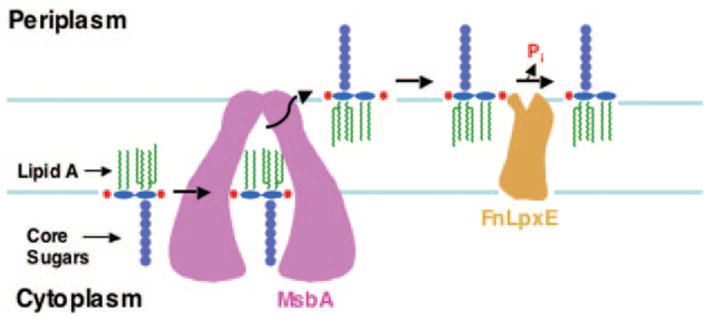

We previously reported that MsbA, an essential ABC transporter related to mammalian Mdr proteins (52), is required for the export of nascent LPS and phospholipids to the outer membrane in E. coli (19, 45). In addition, MsbA is a “flippase” that is necessary for the rapid translocation of newly synthesized LPS across the inner membrane (53). We have now demonstrated that recombinant FnLpxE, an enzyme that selectively dephosphorylates lipid A at the 1-position (Figs. 3 and 5), requires a functional MsbA protein for activity in living E. coli cells (Fig. 8). In contrast, the nine intracellular enzymes that assemble Kdo2-lipid A are MsbA-independent (Fig. 8, lane 3). The active site of FnLpxE is predicted to face the periplasmic side of the inner membrane (38). The fact that FnLpxE requires MsbA in vivo (but not under in vitro assay conditions) provides compelling evidence to support the proposed topography of the 1-phosphatase active site (Fig. 9).

Fig. 9. Proposed model for 1-dephosphorylation of lipid A in the inner membrane of Gram-negative bacteria.

The lipid A and core portions of LPS are synthesized on the inner surface of the inner membrane (3). MsbA, an essential ABC transporter, exports the nascent LPS to the outer surface of the inner membrane (19, 43), where FnLpxE 1-dephosphorylates the lipid A portion of the molecule.

FnLpxE may facilitate the development of novel in vitro LPS flip-flop assays in oriented membrane vesicles, because water is the only co-substrate required. Previously reported periplasmic modifications of lipid A (53), such as the addition of phosphoethanolamine and aminoarabinose groups in polymyxin-resistant mutants, require lipid donor co-substrates (phosphatidylethanolamine and undecaprenyl-phosphate-L-4-aminoarabinose, respectively) (54–56). These substances would also have to be transported across the inner membrane to be available as substrates for periplasmic lipid A modification, complicating the interpretations of in vitro assays.

The LpxE orthologs of F. novicida and R. leguminosarum share sequence homology with each other, primarily in their lipid phosphate phosphatase motifs (Fig. 4). They are both members of the large superfamily of lipid phosphate phosphatases (25), the true substrates of which cannot be predicted without biochemical studies, such as those shown in Figs. 3 and 5. Site-directed mutagenesis has confirmed the absolute requirement of these active site motifs for 1-phosphatase activity.2 Functional FnLpxE is more readily expressed in E. coli and has a much higher apparent specific activity in washed membranes than the previously reported R. leguminosarum LpxE (10). The true specific activities of these phosphatases will have to be determined with homogeneous preparations. In addition, an as yet uncharacterized inhibitor of R. leguminosarum LpxE interferes with its full expression in E. coli membranes prior to solubilization and purification.2 Consequently, the kinds of experiments shown in Figs. 6–8 were not practical with the previously available LpxE ortholog.

The biological activities of the lipid A component of LPS are thought to involve the binding of the negatively charged phosphates groups to cationic amino acid side chains on LPS-binding proteins and receptors (13, 57, 58). Lipid A lacking phosphate groups might help bacteria evade the innate immune system, since they would not be recognized by TLR-4. Furthermore, dephosphorylated lipid A would be expected to have much lower affinity for polymyxin and other cationic antimicrobial peptides (59), conferring resistance to such substances in some organisms (10). This phenomenon allowed us to isolate the FnlpxE gene directly by heterologous expression in E. coli. The dephosphorylated lipid A species found in R. leguminosarum or R. etli (5, 6) similarly might help bacteroids evade the innate immune responses of plants during symbiosis inside root cells. However, the plant can still defend itself against Gram-negative pathogens, which contain phosphorylated lipid A molecules. It will be of interest to isolate and characterize Franciscella and Rhizobium mutants lacking the lipid A phosphatases to assess the effects on intracellular growth, symbiosis, and cationic antimicrobial peptide resistance.

The so-called “monophosphoryl” lipid A preparations (60, 61), which are used as adjuvants (15, 17), retain the immuno-stimulatory properties of lipid A with significantly reduced toxicity. They apparently still signal through TLR-4 but with altered kinetics and cytokine profiles (15). Current methods for preparing monophosphoryl lipid A from natural LPS involve acid hydrolysis at 100 °C (60, 61). This treatment not only removes the 1-phosphate substituent of lipid A but also cleaves the labile Kdo-lipid A linkage (60, 61). Recombinant FnLpxE specifically removes the phosphate from the 1-position of lipid A without disturbing the Kdo residues. As demonstrated in Fig. 7, large amounts of highly purified 1-dephospho-Kdo2-lipid A can be obtained from E. coli expressing FnLpxE. This material, which was not previously available, may prove useful as a novel adjuvant. Synthetic lipid A analogues with a Kdo disaccharide have not been reported, since the Kdo moieties are difficult to incorporate by chemical methods (62).

FnlpxE can also be used to reengineer lipid A structure in living Gram-negative bacteria, such as E. coli (Figs. 6–8) or S. typhimurium (not shown). The effects of controlled 1-dephosphorylation on inflammation and pathogenesis should provide new insights into the interactions of lipid A and LPS with the innate immune system. It will be especially interesting to examine the utility of Salmonella constructs expressing FnLpxE as live oral vaccine candidates (63), possibly in conjunction with other mutations that attenuate virulence (64).

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Francis Nano (University of Victoria, Canada) for providing F. novicida U112. We thank Drs. Mike Reynolds and Middleton Boon Hinckley for providing the Kdo2-[4′-32P]lipid A.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grants R37-GM-51796 (to C. R. H. Raetz) and GM-54882 (to R. J. C.).

The abbreviations used are: LPS, lipopolysaccharide; Kdo, 3-deoxy D-manno-octulosonic acid; MALDI-TOF, matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight.

M. J. Karbarz and C. R. H. Raetz, manuscript in preparation.

The nucleotide sequence(s) reported in this paper has been submitted to the GenBank™/EBI Data Bank with accession number(s) AY713119.

References

- 1.Sjostedt A. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2003;6:66–71. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5274(03)00002-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Raetz CRH. Annu Rev Biochem. 1990;59:129–170. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.59.070190.001021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Raetz CRH, Whitfield C. Annu Rev Biochem. 2002;71:635–700. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.71.110601.135414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vinogradov E, Perry MB, Conlan JW. Eur J Biochem. 2002;269:6112–6118. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2002.03321.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Que NLS, Lin S, Cotter RJ, Raetz CRH. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:28006–28016. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004008200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Que NLS, Ribeiro AA, Raetz CRH. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:28017–28027. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004009200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bhat UR, Forsberg LS, Carlson RW. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:14402–14410. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Price NJP, Jeyaretnam B, Carlson RW, Kadrmas JL, Raetz CRH, Brozek KA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:7352–7356. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.16.7352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brozek KA, Kadrmas JL, Raetz CRH. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:32112–32118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Karbarz MJ, Kalb SR, Cotter RJ, Raetz CRH. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:39269–39279. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305830200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Poltorak A, He X, Smirnova I, Liu MY, Huffel CV, Du X, Birdwell D, Alejos E, Silva M, Galanos C, Freudenberg M, Ricciardi-Castagnoli P, Layton B, Beutler B. Science. 1998;282:2085–2088. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5396.2085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoshino K, Takeuchi O, Kawai T, Sanjo H, Ogawa T, Takeda Y, Takeda K, Akira S. J Immunol. 1999;162:3749–3752. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rietschel ET, Kirikae T, Schade FU, Mamat U, Schmidt G, Loppnow H, Ulmer AJ, Zähringer U, Seydel U, Di Padova F, Schreier M, Brade H. FASEB J. 1994;8:217–225. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.8.2.8119492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Loppnow H, Brade H, Dürrbaum I, Dinarello CA, Kusumoto S, Rietschel ET, Flad HD. J Immunol. 1989;142:3229–3238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Persing DH, Coler RN, Lacy MJ, Johnson DA, Baldridge JR, Hershberg RM, Reed SG. Trends Microbiol. 2002;10:S32–S37. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(02)02426-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sasaki S, Tsuji T, Hamajima K, Fukushima J, Ishii N, Kaneko T, Xin KQ, Mohri H, Aoki I, Okubo T, Nishioka K, Okuda K. Infect Immun. 1997;65:3520–3528. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.9.3520-3528.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baldridge JR, Crane RT. Methods. 1999;19:103–107. doi: 10.1006/meth.1999.0834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kieffer TL, Cowley S, Nano FE, Elkins KL. Microbes Infect. 2003;5:397–403. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(03)00052-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Doerrler WT, Reedy MC, Raetz CRH. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:11461–11464. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C100091200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smith PK, Krohn RI, Hermanson GT, Mallia AK, Gartner FH, Provenzano MD, Fujimoto EK, Goeke NM, Olson BJ, Klenk DC. Anal Biochem. 1985;150:76–85. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(85)90442-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ausubel FM, Brent R, Kingston RE, Moore DD, Seidman JG, Smith JA, Struhl K, editors. Current Protocols in Molecular Biology. John Wiley & Sons, Inc; New York: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. 2. Cold Spring Harbor; Cold Spring Harbor, NY: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wheeler DL, Church DM, Federhen S, Lash AE, Madden TL, Pontius JU, Schuler GD, Schriml LM, Sequeira E, Tatusova TA, Wagner L. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:28–33. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schaffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman DJ. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stukey J, Carman GM. Protein Sci. 1997;6:469–472. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560060226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Clementz T, Bednarski JJ, Raetz CRH. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:12095–12102. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.20.12095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Clementz T, Zhou Z, Raetz CRH. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:10353–10360. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.16.10353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Basu SS, York JD, Raetz CRH. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:11139–11149. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.16.11139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Garrett TA, Kadrmas JL, Raetz CRH. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:21855–21864. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.35.21855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kanipes MI, Lin S, Cotter RJ, Raetz CRH. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:1156–1163. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009019200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Doerrler WT, Raetz CRH. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:36697–36705. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205857200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Raetz CRH, Kennedy EP. J Biol Chem. 1973;248:1098–1105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Raetz CRH, Purcell S, Meyer MV, Qureshi N, Takayama K. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:16080–16088. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bligh EG, Dyer JJ. Can J Biochem Physiol. 1959;37:911–917. doi: 10.1139/o59-099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brabetz W, Muller-Loennies S, Holst O, Brade H. Eur J Biochem. 1997;247:716–724. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.00716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhou Z, Lin S, Cotter RJ, Raetz CRH. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:18503–18514. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.26.18503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhou Z, Ribeiro AA, Lin S, Cotter RJ, Miller SI, Raetz CRH. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:43111–43121. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106960200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Krogh A, Larsson B, von Heijne G, Sonnhammer ELL. J Mol Biol. 2001;305:567–580. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang RF, Kushner SR. Gene (Amst) 1991;100:195–199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Raetz CRH, Dowhan W. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:1235–1238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Costello CE, Vath JE. Methods Enzymol. 1990;193:738–768. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(90)93448-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ribeiro AA, Zhou Z, Raetz CRH. Magn Res Chem. 1999;37:620–630. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chang G, Roth CB. Science. 2001;293:1793–1800. doi: 10.1126/science.293.5536.1793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chang G. J Mol Biol. 2003;330:419–430. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhou Z, White KA, Polissi A, Georgopoulos C, Raetz CRH. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:12466–12475. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.20.12466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mulford CA, Osborn MJ. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1983;80:1159–1163. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.5.1159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bishop RE, Gibbons HS, Guina T, Trent MS, Miller SI, Raetz CRH. EMBO J. 2000;19:5071–5080. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdd507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hwang PM, Choy WY, Lo EI, Chen L, Forman-Kay JD, Raetz CRH, Prive GG, Bishop RE, Kay LE. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:13560–13565. doi: 10.1073/pnas.212344499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Guo L, Lim KB, Gunn JS, Bainbridge B, Darveau RP, Hackett M, Miller SI. Science. 1997;276:250–253. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5310.250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Guo L, Lim KB, Poduje CM, Daniel M, Gunn JS, Hackett M, Miller SI. Cell. 1998;95:189–198. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81750-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Brozek KA, Bulawa CE, Raetz CRH. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:5170–5179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Karow M, Georgopoulos C. Mol Microbiol. 1993;7:69–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01098.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Doerrler WT, Gibbons HS, Raetz CRH. J Biol Chem. 2004 August 10; doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408106200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Trent MS, Raetz CRH. J Endotoxin Res. 2002;8:158. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Trent MS, Ribeiro AA, Lin S, Cotter RJ, Raetz CRH. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:43122–43131. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106961200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Trent MS, Ribeiro AA, Doerrler WT, Lin S, Cotter RJ, Raetz CRH. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:43132–43144. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106962200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gangloff M, Gay NJ. Trends Biochem Sci. 2004;29:294–300. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2004.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Saitoh S, Akashi S, Yamada T, Tanimura N, Kobayashi M, Konno K, Matsumoto F, Fukase K, Kusumoto S, Nagai Y, Kusumoto Y, Kosugi A, Miyake K. Int Immunol. 2004;16:961–969. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxh097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nikaido H, Vaara M. Microbiol Rev. 1985;49:1–32. doi: 10.1128/mr.49.1.1-32.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Qureshi N, Takayama K, Ribi E. J Biol Chem. 1982;257:11808–11815. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Qureshi N, Mascagni P, Ribi E, Takayama K. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:5271–5278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yoshizaki H, Fukuda N, Sato K, Oikawa M, Fukase K, Suda Y, Kusumoto S. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2001;40:1475–1480. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20010417)40:8<1475::AID-ANIE1475>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kang HY, Srinivasan J, Curtiss R., III Infect Immun. 2002;70:1739–1749. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.4.1739-1749.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Low KB, Ittensohn M, Le T, Platt J, Sodi S, Amoss M, Ash O, Carmichael E, Chakraborty A, Fischer J, Lin SL, Luo X, Miller SI, Zheng L, King I, Pawelek JM, Bermudes D. Nat Biotechnol. 1999;17:37–41. doi: 10.1038/5205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Belunis CJ, Raetz CRH. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:9988–9997. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]