Abstract

Connexin26 (Cx26) and Cx30 are predominant isoforms of gap junction channels in the cochlea and play a critical role in hearing. In this study, the cellular distributions of Cx26 and Cx30 in the cochlear sensory epithelium of guinea pigs were examined by immunofluorescent staining and confocal microscopy in whole mounts of the cochlear sensory epithelium and dissociated cell preparations. The expression of Cx26 and Cx30 demonstrated a longitudinal gradient distribution in the epithelium and was reduced threefold from the cochlear apex to base. The reduction was more pronounced in the Deiters cells and pillar cells than in the Hensen cells. Cx26 was expressed in all types of supporting cells, but little Cx30 labeling was seen in the Hensen cells. Cx26 expression in the Hensen cells was concentrated mainly in the second and third rows, forming a distinct band along the sensory epithelium at its outer region. In the dissociated Deiters cells and pillar cells, Cx30 showed dense labeling at the cell bodies and processes in the reticular lamina. Cx26 labeling largely overlapped that of Cx30 in these regions. Cx26 and Cx30 were also coexpressed in the gap junctional plaques between Claudius cells. Neither Cx26 nor Cx30 labeling was seen in the hair cells and spiral ganglion neurons. These observations demonstrate that Cx26 and Cx30 have a longitudinal gradient distribution and distinct cellular expression in the auditory sensory epithelium. This further supports our previous reports that Cx26 and Cx30 can solely and concertedly perform different functions in the cochlea.

Indexing terms: gap junction, cochlear supporting cells, reticular lamina, spiral ganglion, inner ear, nonsyndromic hearing loss

The connexin gene family encodes gap junction channels in mammals. So far, more than 20 connexin genes and their corresponding isoforms have been identified (Willecke et al., 2002). Each connexin shows tissue- or cell-specific expression, and most organs and tissues express more than one connexin (for reviews see Harris, 2001; Evans and Martin, 2002; Willecke et al., 2002). Connexin gap junctions perform electronic and metabolic communications between cells and play important roles in many aspects of cellular and physiological functions. In particular, gap junctions are known to play a critical role in hearing function. Connexin mutations can cause hearing loss and account for 70 – 80% of nonsyndromic hearing loss in children (Kelsell et al., 1997; Denoyelle et al., 1997; Grifa et al., 1999).

The mammalian cochlea is the auditory organ and contains sensory hair cells and nonsensory supporting cells. Gap junctional coupling is extensive in the cochlea (for reviews see Kikuchi et al., 2000; Zhao et al., 2006). In early histological studies, electron microscopy and dye injection demonstrated that intercellular communications existed in the organ of Corti (Jahnke, 1975; Gulley and Reese, 1976; Iurato et al., 1976, 1977; Hama and Saito, 1977; Santos-Sacchi and Dallos, 1983; Santos-Sacchi, 1987; Zwislocki et al., 1992). Kikuchi et al. (1995), using of anti-Cx26 serum and immunohistochemical staining, found that Cx26 was extensively expressed in the cochlea. Two sets of gap junctional networks were identified: the epithelial gap junctional network between the cochlear supporting cells in the auditory sensory epithelium and the connective tissue gap junctional network between the connective tissue cells in the cochlear lateral wall. However, the hair cells showed no Cx26 expression.

By using immunofluorescent staining and Western blot, Cx30 has also been identified as a predominant isoform expressed in the cochlea (Lautermann et al., 1998, 1999). Cx30 is a relatively newly identified member of the connexin gene family and is highly homogenous to Cx26. Seventy-seven percent of the Cx30 amino acid sequences are identical to those of Cx26 (Dahl et al., 1996; Nagy et al., 1997). Most old anti-Cx26 antibodies have been found to cross-react with Cx30. It has been reported that Cx30 is coexpressed with Cx26 in the cochlea (Lautermann et al., 1998, 1999; Forge et al., 2003; Sun et al., 2005). However, the cellular distribution of Cx30 in the cochlea has not been completely described.

Gap junctions in the cochlear sensory epithelium play a crucial role in hearing function. Targeted ablation of Cx26 in the cochlear sensory epithelium can result in hearing loss (Cohen-Salmon et al., 2002). Patch clamp recording has revealed that gap junctional coupling between cochlear supporting cells is composed of multiple homotypic and nonhomotypic (heterotypic/heteromeric) channel configurations with various types of voltage gating and permeability (Zhao and Santos-Sacchi, 2000; Zhao, 2000, 2005a), which can play different roles in hearing function (Zhao, 2003b, 2005a,b). However, the function of gap junctional coupling in the cochlea and the mechanism underlying connexin mutation-induced hearing loss remain largely undetermined.

The gap junctional function relies on cell connexin expression. The epithelial gap junctional network between cochlear supporting cells in the auditory sensory epithelium is a multiple-cell system, including pillar cells, Deiters cells, Hensen cells, and Claudius cells. In this study, the cellular and subcellular distributions of Cx26 and Cx30 expression in the cochlear sensory epithelium have been investigated via double-immunofluorescent staining and confocal microscopy in whole-mount preparation and single dissociated cell preparation. The data reveal that Cx26 and Cx30 have longitudinally gradient distributions in the cochlear sensory epithelium and also have distinct cellular expressions. This further supports our previous report (Zhao, 2005a) that Cx26 and Cx30 play different roles in the intercellular communication in the cochlea. A preliminary report of this work has been presented in abstract form (Zhao, 2003a).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animal preparation and cochlear tissue isolation

In total 19 adult Hartley guinea pigs (250 – 450 g) were used; 10 of them were used in whole-mount preparations and nine in dissociated cell staining. As previously reported (Yu et al., 2006), animals were anesthetized with pentobarbital and decapitated. The temporal bone was then removed. The otic capsule was dissected in a standard extracellular solution (142 NaCl, 5.37 KCl, 1.47 MgCl2, 2 CaCl2, 10 HEPES in mM, 300 mOsm, pH 7.2) to expose the organ of Corti. After the tectorial membrane and stria vascularis were removed, the sensory epithelium (organ of Corti) was picked away with a sharpened needle. The dissected sensory epithelium was collected for staining. In the dissociated cell preparation, the isolated sensory epithelium was further incubated in the standard extracellular solution with trypsin (1 mg/ml) and shaken for 5–15 minutes. Then, the dissociated cells were transferred to a dish for staining. The procedures followed were approved by the University of Kentucky’s Animal Care and Use Committee and conformed to the NIH guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals.

Double-immunofluorescent staining for Cx26 and Cx30

The dissociated sensory epithelia or cochlear cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 minutes. After being washed with 0.1 M PBS three times, the dissociated cells were incubated in a blocking solution (10% goat serum and 1% BSA in PBS) with 0.1% Triton X-100 for 20 minutes. Then, the epithelia or cells were incubated with monoclonal mouse anti-Cx26 and polyclonal rabbit anti-Cx30 antibodies (1:400; catalog No. 33–5800 and 71–2200, respectively; Zymed Laboratories, South San Francisco, CA) in the blocking solution at 4°C overnight. After being washed with 0.1 M PBS three times, the epithelia and cells were reacted to a mixture of the second antibodies, which were Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG and Alexa Fluor 568-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (1: 500; catalog No. A11029 and A11036, respectively; Molecular Probesm, Eugene, OR), in the blocking solution at room temperature for 1 hour. After completely washing out the second antibodies with 0.1 M PBS, staining was observed under a confocal laser scanning microscope.

The commercial antibody to Cx26 used in this experiment was an IgG2a-kappa isotype (immunogen: a 13-amino-acid synthetic peptide derived from the C-terminus of the mouse Cx26 protein), purified from mouse ascites by protein A chromatography. The anti-Cx30 antibody was raised against a synthetic peptide derived from the unique C-terminus of the mouse Cx30 protein. This antibody was epitope affinity-purified from rabbit antiserum. These two antibodies had no cross-reaction with each other and stained a single band of ~26.5 kD and 30 kD, respectively, molecular weight on Western blotting (Zymed manufacturer’s technical information). These antibodies have been used in many recent studies (see, e.g., Forge et al., 2003; Sun et al., 2005), and also no staining was seen when they were used to stain tissues from knockout mice (Cohen-Salmon et al., 2002; Teubner et al., 2003). In addition, we used hair cells that have no connexin expression as an internal control, and no labeling was detected in the hair cells (see Figs. 2D, 9F,G). We also omitted the primary antibody in the experiment. No immunofluorescence was observed.

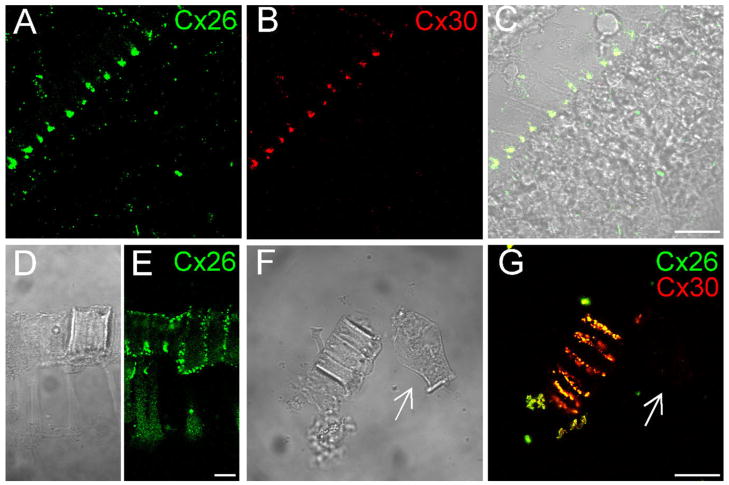

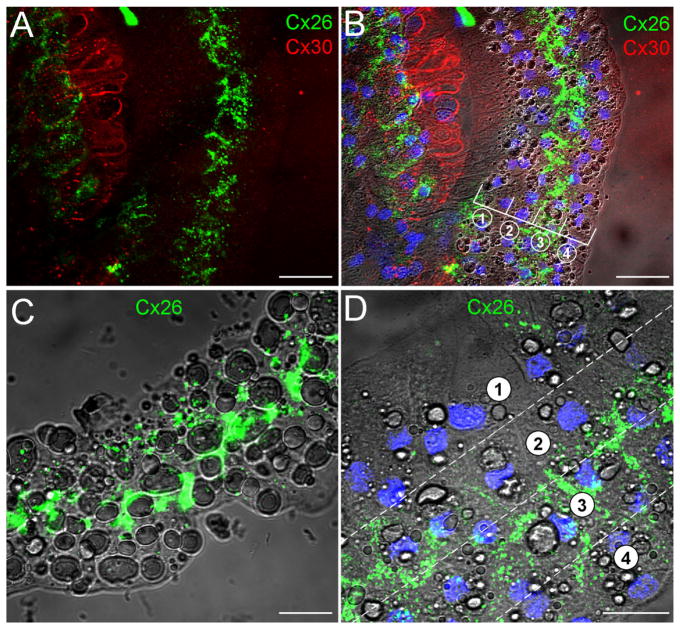

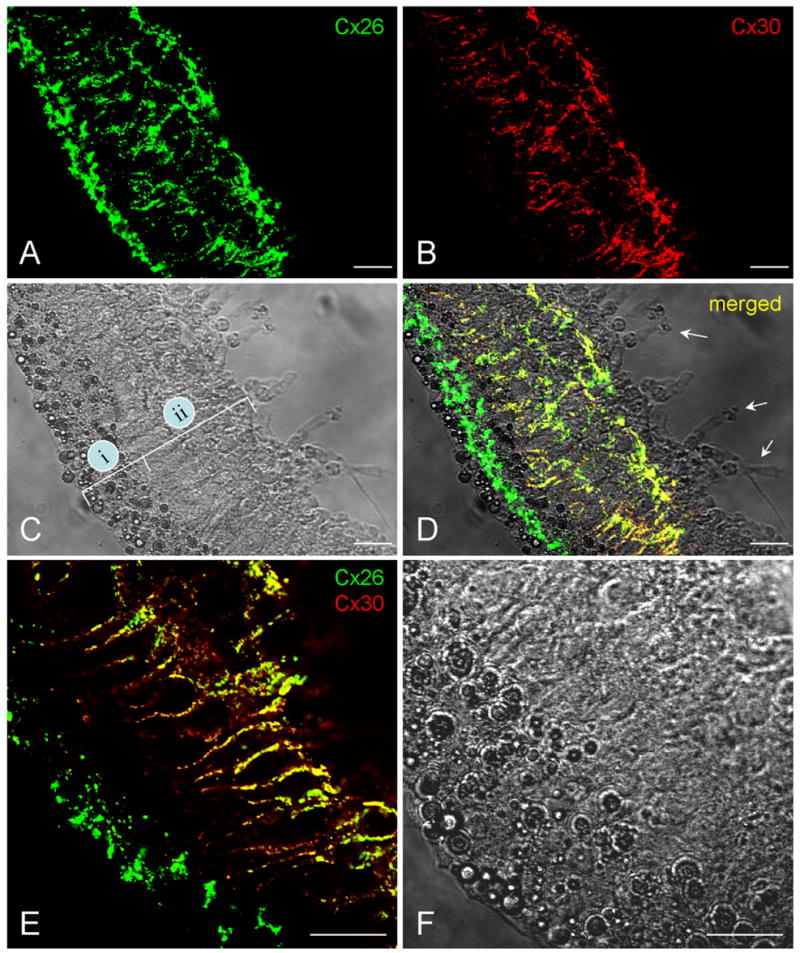

Fig. 2.

Double-immunofluorescent staining of the cochlear sensory epithelium for Cx26 and Cx30 in whole-mount preparation. Green and red represent immunofluorescent staining for Cx26 and Cx30, respectively. A,B: The confocal images of immunofluorescent staining for Cx26 and Cx30. C: Nomarski image. Lines indicate the outer epithelial region (i) and inner epithelial region (ii). D: Merged image of immunofluorescent staining with Nomarski image. Arrows indicate outer hair cells that have no immunofluorescent labeling. E,F: High-magnification images of the epithelium stained for Cx26 and Cx30. F is a Nomarski image in the same field. Scale bars = 25 μm in A–D; 20 μm in E,F.

Fig. 9.

Connexin expression in the reticular lamina. A–C: Confocal images scanned on the apical surface of the reticular lamina. D,E: Cx26 expression in a piece of the dissociated reticular lamina. The reticular lamina shows a thick layer composed of the process heads of pillar cells and Deiters cells. Cx26 labeling is distributed on the outer and inner surfaces of the layer and along the junction lines between the process heads. F,G: Double-immunofluorescent staining for Cx26 and Cx30 in a piece of the dissociated reticular lamina. Arrows indicate an outer hair cell that has no fluorescence labeling in the same field. Scale bars = 20 μm in C,G (apply to A–C,F,G); 10 in E (applies to D,E).

Cellular nucleus staining

In some cases, the cell nuclei were visualized by staining with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, D1306; Molecular Probes). The stock solution of DAPI (5 mg/ml) was made with deionized water. After the reaction to the second antibodies, the epithelia or cells were incubated with a 1:50 dilution of DAPI stock solution for 15 minutes at room temperature (23°C).

Confocal laser scanning microscopy

The stained epithelia or cells were observed under a Leica confocal microscope (Leica TCS SP2) equipped with a ×40 (N/A 1.25) or a ×100 (N/A 1.4) apochromatic oil objective. The argon (488 nm) laser and krypton (568 nm) lasers with 500 –530 nm and 600 – 665 nm emission filters were used for visualization of Alexa Fluor 488 and 568, respectively. DAPI staining was observed under a multiphoton laser with a 388 – 478 nm emission filter. Machine cross-talking was checked by the standard fluorescent slides and turning on/off of one laser in dual-laser excitation. No cross-talk was observed. The fact that distinct Cx26 and Cx30 labeling patterns were seen in the same field (see Figs. 2–5, 7, 9) also indicated the absence of cross-talk in our observations.

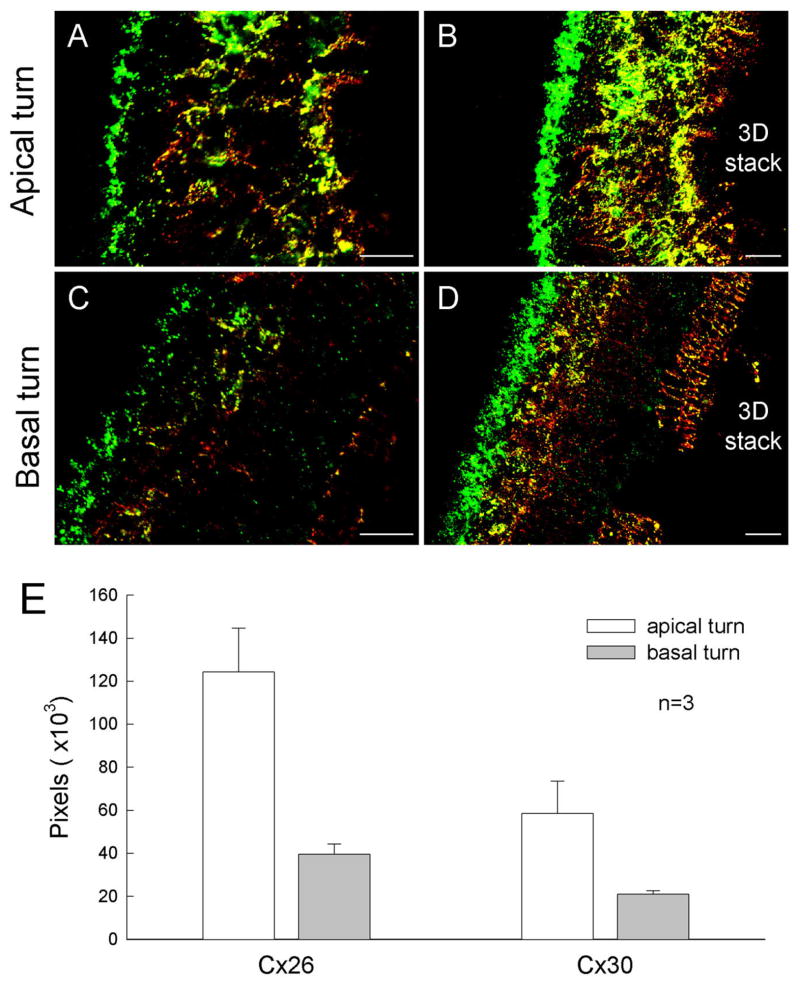

Fig. 5.

Different expressions of Cx26 and Cx30 in the epithelia from the apical and basal turns. A: High-magnification image of immunofluorescent staining of the epithelium from the apical turn. B: Low-magnification image stacked from all scanning sections along the Z-axis. C,D: Single confocal section and 3D-stack immunofluorescent image of the epithelium from the basal turn. E: Quantitative analysis of Cx26 and Cx30 expressions in the apical and basal turns. The epithelia were isolated from the apical and basal turns in the same cochlea and stained at the same time. The pixels of positive staining for Cx26 and Cx30 were separately counted. Data from three animals were averaged. Error bars represent SE. Scale bars = 10 μm in A,C; 25 μm in B,D.

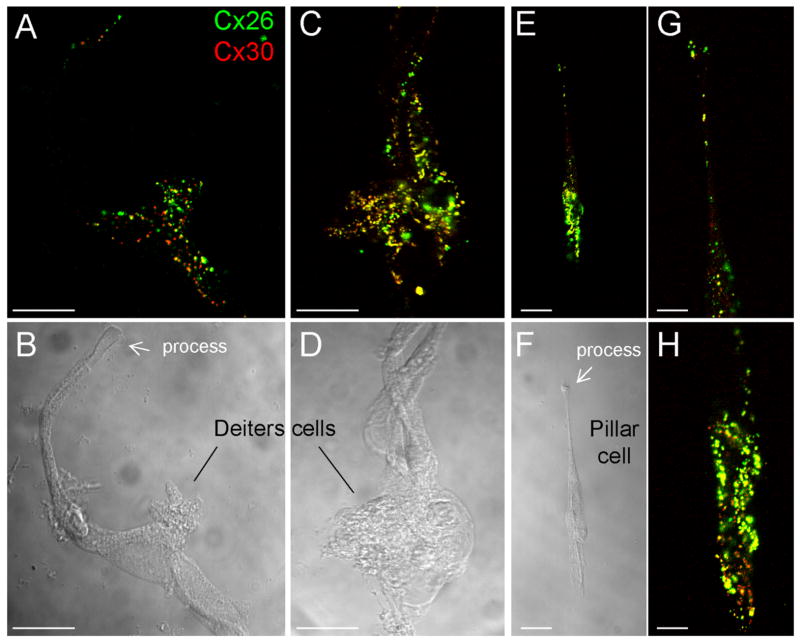

Fig. 7.

A–H: Double-immunofluorescent staining of Deiters cells and a pillar cell for Cx26 and Cx30 in dissociated cell preparation. G and H are high-magnification images of E. Scale bar = 20 μm in A–D; 25μm in E,F; 10 μm in G,H.

Quantitative analysis and image presentation

All images were saved in the TIFF format. Images were assembled in Photoshop (Adobe Systems, Mountain View, CA) for presentation. For quantitative analysis of connexin expression in the cochlear sensory epithelium, serial sections of the confocal image were taken from the apical surface to the basal bottom of the epithelium along the Z-axis. The pixels of Cx26 and Cx30 labeling in 100-μm long epithelium were calculated in each section and then summed. The staining intensities of Cx26 and Cx30 were also measured by use of the “plot profile” function in ImageJ (NIH, Bethesda, MD; Yu et al., 2006). Data were plotted in SigmaPlot (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

RESULTS

Expressions of Cx26 and Cx30 in the cochlear sensory epithelium in whole-mount preparation

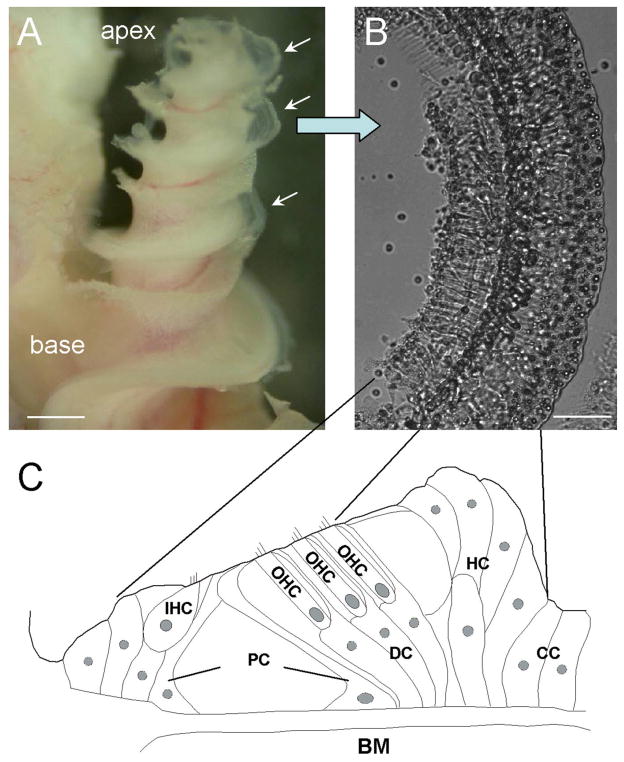

The organ of Corti is a highly organized auditory organ. Auditory sensory hair cells and nonsensory supporting cells are arranged in a specific order in the auditory sensory epithelium (Fig. 1). From the inner to the outer side, inner hair cells, pillar cells, outer hair cells, Deiters cells, Hensen cells, and Claudius cells are sequentially located on the basilar membrane (Fig. 1C). Claudius cells were usually detached from the epithelium during the dissection and were not visible in the isolated epithelium (Fig. 1B). Hensen cells are located at the outer region of the epithelium and are characterized by bright lipid bubbles in their cytoplasm. Deiters cells, outer hair cells, outer and inner pillar cells, and inner hair cells are located in the inner region of the epithelium. In the guinea pig cochlea, there are four rows of Hensen cells, three rows of Deiters cells, one row of outer pillar cells, and one row of inner pillar cells (Fig. 1C).

Fig. 1.

Structure of the cochlea and the organ of Corti. A: Micrograph of the guinea pig cochlea after removal of the bone and stria vascularis. The auditory sensory epithelium is visible and is indicated by arrows. B: The isolated sensory epithelium. C: Diagram of the organ of Corti in a cross-section of the epithelium. IHC, inner hair cell; OHC, outer hair cell; PC, pillar cell; DC, Deiters cell; HC, Hensen cell; CC, Claudius cell; BM, basilar membrane. Scale bars = 0.5 mm in A; 100 μm in B.

Double-immunofluorescent staining of the epithelium for Cx26 and Cx30 in whole-mount preparation showed that Cx26 was expressed at both inner and outer regions of the cochlear sensory epithelium (Fig. 2A–D). At the outer epithelial region, Cx26 labeling was intense and appeared as a distinct band along the epithelium (Fig. 2A,D). The intense labeling band appeared between the second and third rows of Hensen cells (Fig. 3). Cx30 staining at this region was weak and almost undetectable. However, Cx30 labeling at the inner epithelial region was intense (Fig. 2B,D). In high-magnification images, intense staining of Cx30 could be seen in the Deiters cell and pillar cell area (Fig. 2E,F). Cx26 labeling in this inner epithelial region largely overlapped with Cx30. However, outer hair cells (indicated by arrows in Fig. 2D), known as having no connexin expression, had no fluorescent labeling. This negative labeling served as a good internal control for the specificity of connexin staining.

Fig. 3.

Connexin expression in the Hensen cells at the outer epithelial region. A: Immunofluorescent image of double staining of the epithelium for Cx26 and Cx30. B: Superimposed image of fluorescent staining with Nomarski image. Blue represents cell nuclei stained by DAPI. Lines and circled numbers indicate four rows of Hensen cells. C,D: High-magnification images in the Hensen cell region. Cx26 labeling is located mainly at the second and third rows of Hensen cells. Scale bars = 40 μm in A–C; 20 μm in D.

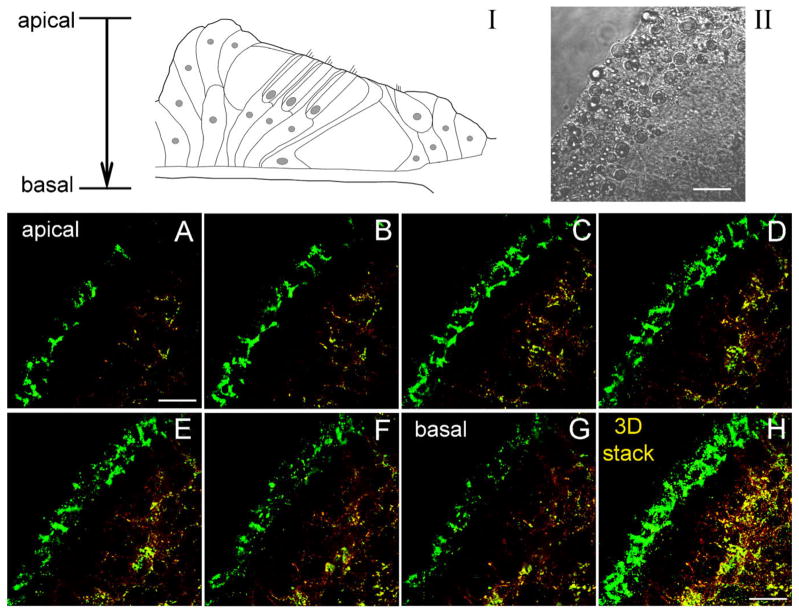

To examine connexin expression in the epithelium along the Z-depth axis, serial confocal sections were scanned from its apical surface down to the basal bottom (Fig. 4). Both Cx26 and Cx30 labeling can been seen at the inner epithelial region in all sections. The labeling was strong and dense in the sections at the middle level corresponding to the Deiters cell and pillar cell bodies (Fig. 4C–F). The stack image (Fig. 4H) also showed the intensive labeling of Cx26 and Cx30 at the inner epithelial region but only Cx26 labeling at the outer epithelial region.

Fig. 4.

Immunofluorescent staining for Cx26 and Cx30 in the cochlear sensory epithelium along the Z-axis. Serial confocal sections were scanned by a 2.2-μm step from the apical epithelial surface down to its basal bottom (I). Green and red colors represent Cx26 and Cx30 staining, respectively. II is a Nomarski image. Scale bars = 10 μm in I,II; 10 μm in A,H (apply to A–H).

Gradient distributions of Cx26 and Cx30 in the cochlear sensory epithelium

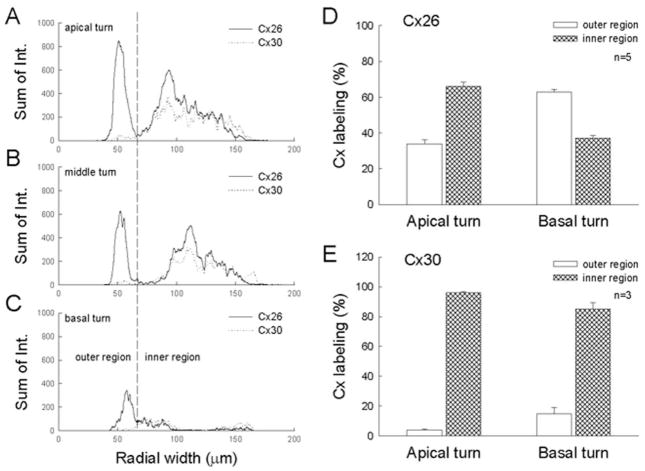

Cx26 and Cx30 expressions showed a gradient reduction along the longitudinal direction of the epithelium. Figure 5 shows Cx26 and Cx30 staining of the sensory epithelia in the apical and basal turns isolated from the same cochlea. The intensity of both Cx26 and Cx30 staining was weaker in the basal turn than in the apical turn. The puncta of Cx26 and Cx30 labeling in the basal turn also appeared sparse (Fig. 5A–D). Quantitative analysis showed that Cx26 labeling in the apical and basal turns was 124.3 ± 20.4 × 103 and 39.6 ± 4.8 × 103 pixels, respectively; Cx30 labeling was 58.5 ± 15.0 × 103 and 21.1 ± 1.6 × 103 pixels. Expressions of both Cx26 and Cx30 in the basal turn were reduced by about threefold (Fig. 5E).

The reduction in expressions of Cx26 and Cx30 was more pronounced at the inner epithelial region than at the outer epithelial region (Fig. 6). The relative distribution of Cx26 in the apical turn at the inner and outer epithelial regions was 66.17% ± 5.85% and 33.83% ± 2.39% (n = 5), respectively. This distribution became opposite and changed to 37.1% ± 1.32% and 62.9% ± 1.37% (n = 3) in the basal turn (Fig. 6D). The Cx26 distribution at the inner epithelial region was reduced from 66.17% ± 5.85% to 37.1% ± 1.32%, or about twofold. The ratios of Cx30 distribution at the inner and outer epithelial regions in the apical and basal turns were similar and were not apparently changed (Fig. 6E). The majority of Cx30 expression was still in the inner epithelial region.

Fig. 6.

Comparison of Cx26 and Cx30 expressions at the inner and outer epithelial regions in the apical and basal turns. A–C: Intensities of Cx26 and Cx30 staining were measured along the radial direction of the epithelia from the apical, middle, and basal turns in the same cochlea. The epithelium was serially scanned along the Z-axis, and the intensities of staining for Cx26 and Cx30 were separately measured in each section, then summed. D,E: Percentages of Cx26 and Cx30 distributions at the inner and outer epithelial regions in the apical and basal turns. Error bars represent SE.

Subcellular distributions of Cx26 and Cx30 in the cochlear cells

The cellular and subcellular distribution of connexin expression in the cochlear cells was further investigated in the dissociated cell preparation (Figs. 7–9). In the dissociated Deiters cells, dense labeling of Cx26 and Cx30 was found at the cell body and cup area, on the base of which the outer hair cell sits in vivo (Fig. 7A–D). Cx26 labeling largely overlapped with Cx30 labeling in these regions (Fig. 7A,C). Puncta of Cx26 and Cx30 labeling were also visible in the apical processes of the Deiters cells (Fig. 7A). Connexin expression in the pillar cell was similar to that in the Deiters cells. Both Cx26 and Cx30 were expressed in the pillar cell, which had dense labeling of its process and cell body (Fig. 7E–H). Cx26 labeling also largely overlapped with Cx30 expression.

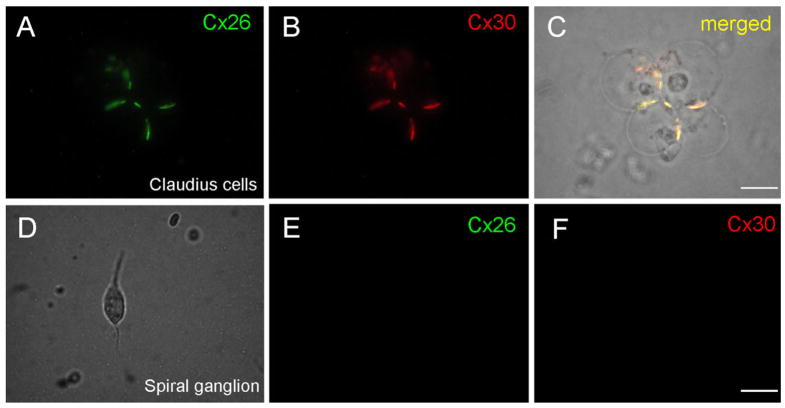

In the Claudius cells, strong Cx26 and Cx30 double-labeling was located on the junctional membrane between cells and formed large gap junctional plaques (Fig. 8A–C). However, there was no Cx26 or Cx30 labeling in the spiral ganglion neuron (Fig. 8D–F) or in the dissociated outer hair cell (indicated by arrow in Fig. 9F,G).

Fig. 8.

A–C: Double-immunofluorescent staining of Claudius cells for Cx26 and Cx30. C is a merged image showing coexpression of Cx26 and Cx30 in the same gap junctional plaques between cells. D–F: Immunofluorescent images of a spiral ganglion cell staining for Cx26 and Cx30. There is no fluorescent labeling in the cochlear spiral ganglion neuron. Scale bars = 15 μm in C,F (apply to A–F).

Gap junctional coupling in the reticular lamina

The reticular lamina is composed of the apical processes of pillar cells and Deiters cells and the cuticular plate of outer hair cells. Double-immunofluorescent staining showed that Cx26 and Cx30 were coexpressed in the reticular lamina (Fig. 9). Coexpression of Cx26 and Cx30 regularly appeared at the junctions between the processes of Deiters cells and pillar cells on the apical surface of the reticular lamina (Fig. 9A–C). In the dissociated reticular lamina (Fig. 9D–G), the puncta of Cx26 and Cx30 labeling were distributed along the junctional lines between the process heads within the lamina (Fig. 9E,G).

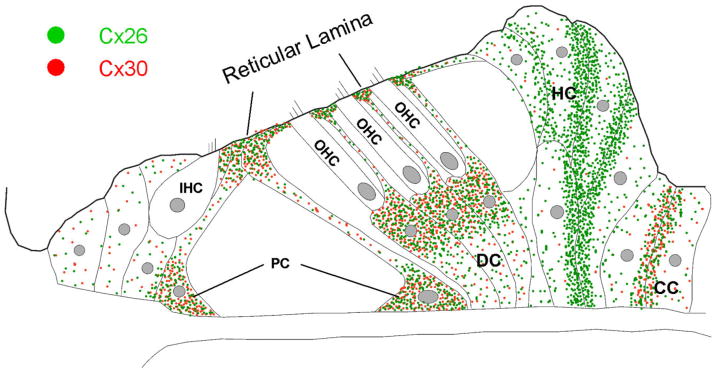

Figure 10 shows a schematic diagram of the cellular distribution of Cx26 and Cx30 expression in the cochlear sensory epithelium. Cx26 and Cx30 were coexpressed in pillar cells, Deiters cells, and Claudius cells. Both Cx26 and Cx30 had high expression at the cell bodies of pillar cells and Deiters cells near the hair cell area, at their processes in the reticular lamina, and between the Claudius cells. In these regions, Cx26 and Cx30 distributions largely overlapped in the same puncta or gap junctional plaques. Cx26 was also predominantly expressed between the second and the third rows of Hensen cells at the outer epithelial region, where Cx30 expression was low and almost undetectable. Neither Cx26 nor Cx30 labeling was found in the hair cells and spiral ganglion neurons. Cx26 and Cx30 showed distinct distributions in the cochlear sensory epithelium.

Fig. 10.

Schematic diagram of the cellular and subcellular distributions of Cx26 and Cx30 in the cochlear sensory epithelium. Green and red spots represent Cx26 and Cx30 expression, respectively. IHC, inner hair cell; OHC, outer hair cell; PC, pillar cell; DC, Deiters cell; HC, Hensen cell; CC, Claudius cell.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we found that Cx26 and Cx30 had gradient expression in the cochlear sensory epithelium in the longitudinal direction. Cx26 and Cx30 expression were reduced by threefold from the cochlear apex to base (Figs. 5, 6). The sensory epithelium in the basal turn is responsible for high-frequency hearing. Clinically, it has been found that Cx26 mutations cause a range of phenotypes from mild to profound hearing loss and that loss of hearing in the high-frequency range is a characteristic feature of the audiograms of affected patients (Wilcox et al., 2000). In the mice with ablation of Cx26 in the sensory epithelium, hearing loss is also more pronounced in the high-frequency range than in the low- and middle-frequency ranges (Cohen-Salmon et al., 2002). The gap junction in the basal turn appears more fragile than that in the apical turn and is easily impaired. Low expressions of connexins can induce gap junctional function in the basal region being susceptible and vulnerable to impairment. Low connexin expression may also make more apparent a reduction in the gap junctional function in the basal turn.

We also found that Cx26 and Cx30 had cell-specific expressions and distinct distributions in the cochlear sensory epithelium. Cx26 had dominant expression in the Hensen cell region (Figs. 2–5), whereas Cx30 had high expression in the Deiters cells and pillar cells (Figs. 2, 4, 5), especially at the cell bodies near the outer hair cell basal pole (Figs. 4, 7). It has been reported that Cx26 and Cx30 play different roles in the cochlea (Zhao, 2003b, 2005a). Gap junctions in the cochlea have different permeabilities and demonstrate significant charge selectivity; Cx26 is primarily responsible for anionic permeation (Zhao, 2005a). In vitro, Cx30 homotypic channels show a permeability preference for cations and are impermeable to the negatively charged dye trace Lucifer yellow (Manthey et al., 2001; Beltramello et al., 2003). One of the hypothesized gap junctional functions in the cochlea is to remove potassium ions released by the hair cell and nerve endings near the hair cell basal area to avoid the potassium accumulation (Santos-Sacchi, 1991; Kikuchi et al., 1995, 2000; Spicer and Schulte, 1998; Zhao, 2005b). Dense distribution of Cx30 in the inner epithelial region near the inner and outer hair cells (Fig. 7) facilitates the transfer of K+ ions to perform this proposed gap junctional function in the cochlea.

Cx26 labeling was shown to be largely overlapping with Cx30 expression at the bodies of Deiters cells and pillar cells and between Claudius cells (Figs. 4, 7, 8). In previous patch clamp recording studies, we found that Cx26 and Cx30 can form heterotypic and/or heteromeric channels with asymmetric voltage gating between cochlear supporting cells (Zhao and Santos-Sacchi, 2000; Zhao, 2003b). This asymmetric voltage gating can induce directional transjunction transport (Zhao, 2000). Coassembling of Cx26 and Cx30 into the homomeric connexons (hemichannels) has also been demonstrated by immunoprecipitation (Forge et al., 2003; Sun et al., 2005). Moreover, it has been found that some deafness-associated Cx26 mutants (e.g., mutations of V84L, V95M, and E114G) can form functional homotypic gap junctional channels, but not heterotypic channels, between transfectants (Choung et al., 2002; Thonnissen et al., 2002; Bruzzone et al., 2003; Wang et al., 2003), indicating that heterotypic or heteromeric channels could play important roles in hearing function.

Cx26 and Cx30 were also highly expressed at the processes of Deiters cells and pillar cells in the reticular lamina (Figs. 7, 9). The reticular lamina is formed by the apical processes of inner and outer pillar cells and the phalangeal processes of Deiters cells joining with the cuticular plates of hair cells by tight and adherens junctions (Leonova and Raphael, 1997). In vivo, the reticular lamina acts as an ionic barrier to separate the low-K+ perilymph from the high-K+ endolymph and maintains normal electrochemical gradients in the organ of Corti. Disruption of the integrity of the reticular lamina can result in endolymph K+ leaking into the perilymph and consequently cause serious ototoxicity and hearing loss (Duvall and Rhodes, 1967; Konishi and Kelsey, 1973; Marcus et al., 1981). In the Cx26-deficient mice, cochlear hair cells and supporting cells start to degenerate after the onset of hearing; this has been thought to result from potassium ototoxicity caused by loss of integrity of the reticular lamina (Cohen-Salmon et al., 2002). Our finding that Cx26 and Cx30 had high expression in the reticular lamina (Figs. 7, 9) supports this concept and also implies that gap junctional coupling may play a critical role in maintaining the integrity of the reticular lamina.

In this experiment, we found that Cx26 and Cx30 had no expression in spiral ganglion neurons (Fig. 8D–F). This is consistent with the idea that the pathology underlying Cx26 and Cx30 mutation-induced hearing loss occurs mainly in the cochlea. Connexin mutations are associated with a high incidence of hearing loss (Kelsell et al., 1997; Denoyelle et al., 1997; Grifa et al., 1999). In patients with connexin mutations, auditory function tests demonstrate a reduced or absent distortion product of otoacoustic emission (DPOAE; Engel-Yeger et al., 2002, 2003). Local cochlear application of gap junctional blockers also causes a large reduction in DPOAE in the gerbil (Spiess et al., 2002). The DPOAE arises from the active cochlear mechanics, contributed mainly by outer hair cell electromotility in mammals (Liberman et al., 2002; Cheatham et al., 2004). However, there is neither connexin expression nor gap junctional coupling in the auditory sensory hair cells (Fig. 9F,G; see also Kikuchi et al., 1995; Lautermann et al., 1998; Forge et al., 1999; Zhao and Santos-Sacchi, 1999; Zhao, 2000). We recently found that, under physiological conditions, connexin hemichannels in the cochlear supporting cells can open to release ATP to regulate outer hair cell electromotility (Zhao et al., 2005). This reveals a connexin-mediated intercellular signaling pathway between cochlear supporting cells and hair cells to control hearing function. In this experiment, Cx26 and Cx30 were visibly expressed on the epithelial surface (Figs. 4, 9), implying that connexins could function as hemichannels on the surface of the epithelium. This finding provides further evidence of a connexin-mediated intercellular signaling pathway in the cochlea.

Acknowledgments

National Institute of Deafness and Other Communication Disorders; Grant number: DC 05989.

We thank Mary G. Engle for technical support in confocal microscopy.

LITERATURE CITED

- Beltramello M, Bicego M, Piazza V, Ciubotaru CD, Mammano F, D’Andrea P. Permeability and gating properties of human connexins 26 and 30 expressed in HeLa cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;305:1024–1033. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(03)00868-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruzzone R, Veronesi V, Gomes D, Bicego M, Duval N, Marlin S, Petit C, D’Andrea P, White TW. Loss-of-function and residual channel activity of connexin26 mutations associated with nonsyndromic deafness. FEBS Lett. 2003;533:79–88. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)03755-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheatham MA, Huynh KH, Gao J, Zuo J, Dallos P. Cochlear function in Prestin knockout mice. J Physiol. 2004;560:821– 830. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.069559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choung YH, Moon SK, Park HJ. Functional study of GJB2 in hereditary hearing loss. Laryngoscope. 2002;112:1667–1671. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200209000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen-Salmon M, Ott T, Michel V, Hardelin JP, Perfettini I, Eybalin M, Wu T, Marcus DC, Wangemann P, Willecke K, Petit C. Targeted ablation of connexin26 in the inner ear epithelial gap junction network causes hearing impairment and cell death. Curr Biol. 2002;12:1106–1111. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00904-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahl E, Manthey D, Chen Y, Schwarz HJ, Chang YS, Lalley PA, Nicholson BJ, Willecke K. Molecular cloning and functional expression of mouse connexin-30, a gap junction gene highly expressed in adult brain and skin. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:17903–17910. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.30.17903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denoyelle F, Weil D, Maw MA, Wilcox SA, Lench NJ, Allen-Powell DR, Osborn AH, Dahl HH, Middleton A, Houseman MJ, Dode C, Marlin S, Boulila-ElGaied A, Grati M, Ayadi H, BenArab S, Bitoun P, Lina-Granade G, Godet J, Mustapha M, Loiselet J, El-Zir E, Aubois A, Joannard A, Petit C, et al. Prelingual deafness: high prevalence of a 30delG mutation in the connexin 26 gene. Hum Mol Genet. 1997;6:2173–2177. doi: 10.1093/hmg/6.12.2173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duvall AJ, 3rd, Rhodes VT. Ultrastructure of the organ of Corti following intermixing of cochlear fluids. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1967;76:688–708. doi: 10.1177/000348946707600312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel-Yeger B, Zaaroura S, Zlotogora J, Shalev S, Hujeirat Y, Carrasquillo M, Barges S, Pratt H. The effects of a connexin 26 mutation—35delG— on otoacoustic emissions and brainstem evoked potentials: homozygotes and carriers. Hear Res. 2002;163:93–100. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(01)00386-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel-Yeger B, Zaaroura S, Zlotogora J, Shalev S, Hujeirat Y, Carrasquillo M, Saleh B, Pratt H. Otoacoustic emissions and brainstem evoked potentials in compound carriers of connexin 26 mutations. Hear Res. 2003;175:140–151. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(02)00719-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans WH, Martin PE. Gap junctions: structure and function [review] Mol Membrane Biol. 2002;19:121–136. doi: 10.1080/09687680210139839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forge A, Becker D, Casalotti S, Edwards J, Evans WH, Lench N, Souter M. Gap junctions and connexin expression in the inner ear. Novartis Found Symp. 1999;219:134–150. 151–163. doi: 10.1002/9780470515587.ch9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forge A, Becker D, Casalotti S, Edwards J, Marziano N, Nevill G. Gap junctions in the inner ear: comparison of distribution patterns in different vertebrates and assessement of connexin composition in mammals. J Comp Neurol. 2003;467:207–231. doi: 10.1002/cne.10916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grifa A, Wagner CA, D’Ambrosio L, Melchionda S, Bernardi F, Lopez-Bigas N, Rabionet R, Arbones M, Monica MD, Estivill X, Zelante L, Lang F, Gasparini P. Mutations in GJB6 cause nonsyndromic autosomal dominant deafness at DFNA3 locus. Nat Genet. 1999;23:16–18. doi: 10.1038/12612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulley RL, Reese TS. Intercellular junctions in the reticular lamina of the organ of Corti. J Neurocytol. 1976;5:479–507. doi: 10.1007/BF01181652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hama K, Saito K. Gap junctions between the supporting cells in some acoustico-vestibular receptors. J Neurocytol. 1977;6:1–12. doi: 10.1007/BF01175410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris AL. Emerging issues of connexin channels: biophysics fills the gap. Q Rev Biophys. 2001;34:325– 472. doi: 10.1017/s0033583501003705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iurato S, Franke K, Luciano L, Wermbter G, Pannese E, Reale E. Intercellular junctions in the organ of Corti as revealed by freeze fracturing. Acta Otolaryngol. 1976;82:57– 69. doi: 10.3109/00016487609120863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iurato S, Franke KD, Luciano L, Wermbter G, Pannese F, Reale E. The junctional complexes among the cells of the organ of Corti as revealed by freeze-fracturing. Adv Otorhinolaryngol. 1977;22:76–80. doi: 10.1159/000399490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahnke K. The fine structure of freeze-fractured intercellular junctions in the guinea pig inner ear. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl. 1975;336:1– 40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelsell DP, Dunlop J, Stevens HP, Lench NJ, Liang JN, Parry G, Mueller RF, Leigh IM. Connexin 26 mutations in hereditary nonsyndromic sensorineural deafness. Nature. 1997;387:80–83. doi: 10.1038/387080a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kikuchi T, Kimura RS, Paul DL, Adams JC. Gap junctions in the rat cochlea: immunohistochemical and ultrastructural analysis. Anat Embryol. 1995;191:101–118. doi: 10.1007/BF00186783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kikuchi T, Kimura RS, Paul DL, Takasaka T, Adams JC. Gap junction systems in the mammalian cochlea. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2000;32:163–166. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(99)00076-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konishi T, Kelsey E. Effect of potassium deficiency on cochlear potentials and cation contents of the endolymph. Acta Otolaryngol. 1973;76:410–418. doi: 10.3109/00016487309121529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lautermann J, ten Cate WJ, Altenhoff P, Grummer R, Traub O, Frank H, Jahnke K, Winterhager E. Expression of the gap-junction connexins 26 and 30 in the rat cochlea. Cell Tissue Res. 1998;294:415– 420. doi: 10.1007/s004410051192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lautermann J, Frank HG, Jahnke K, Traub O, Winterhager E. Developmental expression patterns of connexin26 and -30 in the rat cochlea. Dev Genet. 1999;25:306–311. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-6408(1999)25:4<306::AID-DVG4>3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonova EV, Raphael Y. Organization of cell junctions and cytoskeleton in the reticular lamina in normal and ototoxically damaged organ of Corti. Hear Res. 1997;113:14–28. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(97)00130-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liberman MC, Gao J, He DZ, Wu X, Jia S, Zuo J. Prestin is required for electromotility of the outer hair cell and for the cochlear amplifier. Nature. 2002;419:300–304. doi: 10.1038/nature01059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manthey D, Banach K, Desplantez T, Lee CG, Kozak CA, Traub O, Weingart R, Willecke K. Intracellular domains of mouse connexin26 and -30 affect diffusional and electrical properties of gap junction channels. J Membrane Biol. 2001;18:137–148. doi: 10.1007/s00232-001-0017-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcus DC, Marcus NY, Thalmann R. Changes in cation contents of stria vascularis with ouabain and potassium-free perfusion. Hear Res. 1981;4:149–160. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(81)90002-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagy JI, Ochalski PA, Li J, Hertzberg EL. Evidence for the co-localization of another connexin with connexin-43 at astrocytic gap junctions in rat brain. Neuroscience. 1997;78:533–548. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(96)00584-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos-Sacchi J. Cell coupling differs in the in vitro and in vivo organ of Corti. Hear Res. 1987;25:227–232. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(87)90094-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos-Sacchi J. Isolated supporting cells from the organ of Corti: some whole cell electrical characteristics and estimates of gap junctional conductance. Hear Res. 1991;52:89–98. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(91)90190-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos-Sacchi J, Dallos P. Intercellular communication in the supporting cells of the organ of Corti. Hear Res. 1983;9:317–326. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(83)90034-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spicer SS, Schulte BA. Evidence for a medial K+ recycling pathway from inner hair cells. Hear Res. 1998;118:1–12. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(98)00006-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiess AC, Lang H, Schulte BA, Spicer SS, Schmiedt RA. Effects of gap junction uncoupling in the gerbil cochlea. Laryngoscope. 2002;112:1635–1641. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200209000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun J, Ahmad S, Chen S, Tang W, Zhang Y, Chen P, Lin X. Cochlear gap junctions coassembled from Cx26 and 30 show faster intercellular Ca2+ signaling than homomeric counterparts. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2005;288:C613– 623. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00341.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teubner B, Michel V, Pesch J, Lautermann J, Cohen-Salmon M, Sohl G, Jahnke K, Winterhager E, Herberhold C, Hardelin JP, Petit C, Willecke K. Connexin30 (Gjb6)-deficiency causes severe hearing impairment and lack of endocochlear potential. Hum Mol Genet. 2003;12:13–21. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thonnissen E, Rabionet R, Arbones ML, Estivill X, Willecke K, Ott T. Human connexin26 (GJB2) deafness mutations affect the function of gap junction channels at different levels of protein expression. Hum Genet. 2002;111:190–197. doi: 10.1007/s00439-002-0750-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang HL, Chang WT, Li AH, Yeh TH, Wu CY, Chen MS, Huang PC. Functional analysis of connexin-26 mutants associated with hereditary recessive deafness. J Neurochem. 2003;84:735–742. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01555.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilcox SA, Saunders K, Osborn AH, Arnold A, Wunderlich J, Kelly T, Collins V, Wilcox LJ, McKinlay Gardner RJ, Kamarinos M, Cone- Wesson B, Williamson R, Dahl HH. High frequency hearing loss correlated with mutations in the GJB2 gene. Hum Genet. 2000;106:399–405. doi: 10.1007/s004390000273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willecke K, Eiberger J, Degen J, Eckardt D, Romualdi A, Guldenagel M, Deutsch U, Sohl G. Structural and functional diversity of connexin genes in the mouse and human genome. Biol Chem. 2002;383:725–737. doi: 10.1515/BC.2002.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu N, Zhu ML, Zhao HB. Prestin is expressed on the whole outer hair cell basolateral surface. Brain Res. 2006;1095:51–58. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao HB. Directional rectification of gap junctional voltage gating between Deiters cells in the inner ear of guinea pig. Neurosci Lett. 2000;296:105–108. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(00)01626-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao HB. Hemichannel activities in native cochlear supporting cells. The 47th Biophysical Society Annual Meeting; San Antonio, Texas. March 1–5; 2003a. [ http://www.biophysic.org] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao HB. Biophysical properties and functional analysis of inner ear gap junctions for deafness mechanisms of nonsyndromic hearing loss. Proceedings of the 9th International Meeting on Gap Junctions, University of Cambridge; Cambridge, United Kingdom. August 23–28.2003b. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao HB. Connexin26 is responsible for anionic molecule permeability in the cochlea for intercellular signalling and metabolic communications. Eur J Neurosci. 2005a;21:1859–1868. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04031.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao HB. What is the function of Connexin26 in the cochlea? Potassium recycling or intercellular signaling and nutrient/energy supplies?. Proceedings of the 5th Interantional Symposium: Meniere’s Disease and Inner Ear Homeostasis Disorders; Los Angeles, CA. April 2–5; 2005b. pp. 254–255. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao HB, Santos-Sacchi J. Auditory collusion and a coupled couple of outer hair cells. Nature. 1999;399:359–362. doi: 10.1038/20686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao HB, Santos-Sacchi J. Voltage gating of gap junctions in cochlear supporting cells: evidence for nonhomotypic channels. J Membrane Biol. 2000;175:17–24. doi: 10.1007/s002320001051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao HB, Yu N, Fleming CR. Gap junctional hemichannel-mediated ATP release and hearing controls in the inner ear. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:18724–18729. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506481102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao HB, Kikuchi T, Ngezahayo A, White TW. Gap junctions and cochlear homeostasis. J Membrane Biol. 2006;209:177–186. doi: 10.1007/s00232-005-0832-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zwislocki JJ, Slepecky NB, Cefaratti LK, Smith RL. Ionic coupling among cells in the organ of Corti. Hear Res. 1992;57:175–194. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(92)90150-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]