Abstract

Pelvic discontinuity is a complex entity with a high surgical complication rate and no standardized treatment to date. Revision hip arthroplasty in cases of massive bone loss remains a difficult and unsolved problem. The goal of the surgeon is to preserve limb function by restoring bone stock and the biomechanics of the hip. In cases of severe acetabular bone loss, biologic fixation is often inadequate, requiring extensive bone grafting and reconstructive cages. Reconstructive cages are the most commonly used devices and are designed to bridge bone defects, protect the bone graft, and reestablish the rotation center of the hip. A major limitation of current cages is that they do not allow for biologic fixation. We review the options for treating patients with massive bone loss and pelvic discontinuity and discuss therapeutic options and the clinical and radiological criteria for success.

Keywords: reconstructive cages, massive bone loss, revision hip arthroplasty, pelvic discontinuity

Introduction

Reports on the treatment of massive acetabular bone loss and pelvic discontinuity are rare [1, 2], and there is no consensus on the best therapeutic option. Bone defects involving less than 50% of the acetabulum are considered mild-to-moderate. Defects involving more than 50% are defined as massive.

Biologic fixation in hip revision cases with moderate osseous pelvic defects requires sufficient contact between bone and the acetabular cup, thus allowing for primary stability and bone ingrowth. A 50% contact between a porous cup and native bone is considered the lower limit for reliable reconstruction using these devices. Less extensive surface contacts with native bone can be accepted if there is good support with the rim or the dome of the acetabulum. Successful surgical treatment options for moderate acetabular defects include superior placement of the acetabular component [3, 4], the use of jumbo cups [5], oblong cups [6, 7], and structural allografts.

Massive bone loss is a more complex entity, especially in the presence of distorted acetabular geometry, pelvic discontinuity, or severely damaged or deficient acetabular columns.

Osteolysis, aggressive acetabular reaming, or stress fractures of the acetabulum can lead to pelvic discontinuity in patients who undergo hip arthroplasty. In a report from the Mayo Clinic [2], pelvic discontinuity was present in 0.9% of all hip revisions. Female sex, rheumatoid arthritis, previous pelvic radiation, and massive bone loss were considered predisposing factors. These defects are currently indications for antiprotrusio rings, reconstruction cages [8, 9], or custom cages.

Reconstruction cages provide the basis for bone repair. They allow grafting and bone augmentation, bridge areas of bone loss, and give support to the cup liner. They also distribute forces over a large surface area, thereby reducing the risk of implant migration.

Different designs are available, but basic characteristics are common to most of them. Unfortunately, cages have a high complication rate because of the nature of the procedure and the extent of bone loss. The most common complication from the current generation of rings and cages is the medium- to long-term loss of fixation [10]. New designs, custom components, and modular, porous metal augments try to minimize these mechanical and biological failures. Follow-up of these novel designs is limited, but some reports offer encouraging early results [11-13]. The treatment of pelvic discontinuity has traditionally been affected by complications and technical difficulties.

A review of the literature on pelvic discontinuity reveals several major problems:

The wide spectrum of acetabular bone loss classifications.

The varied surgical instrumentation and devices available.

Scarce and small report series and no randomized prospective studies.

The lack of consensus on the best type of graft to be used (some favoring a stronger initial construction using structural allografts whereas others prefer morselized bone graft in the hope of a more rapid and predictable incorporation of the graft).

The high rate of surgical complications and mechanical failures.

Specific clinical success and radiological interpretation criteria have yet to be defined for this complex entity.

Clinical and radiological evaluation of massive acetabular defects and pelvic discontinuity

Preoperative evaluation

Pelvic discontinuity can be defined as a loss of bone in both the anterior and posterior columns of the acetabulum that disrupts the continuity of the superior and inferior parts of the pelvis (Figs. 1 and 2). It can be identified in preoperative radiographs as a visible fracture line or bone defect that includes both columns of the acetabulum or as a medial shift or rotation of the inferior hemipelvis in relation to the superior hemipelvis that can be viewed as an interruption of the continuity of the Köhler line or asymmetry of the obturator foramen in the absence of previous abnormalities on standard anteroposterior pelvic radiographs [2]. In other cases, the interpreter of the radiograph underestimates the extent of an osteolytic lesion [14], and pelvic discontinuity is not evidenced until the entire acetabulum has been exposed surgically (Figs. 3, 4, 5, and 6).

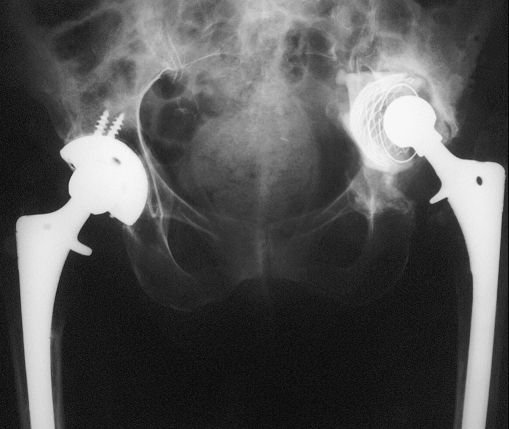

Fig. 1.

Acetabular protrusio. Mild elevation of the hip center

Fig. 2.

Acetabular protrusio and marked proximal migration 4 months later

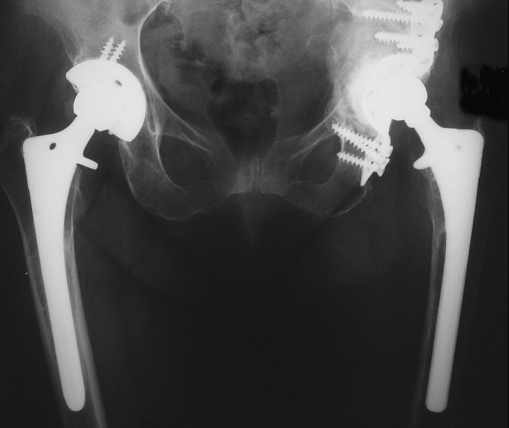

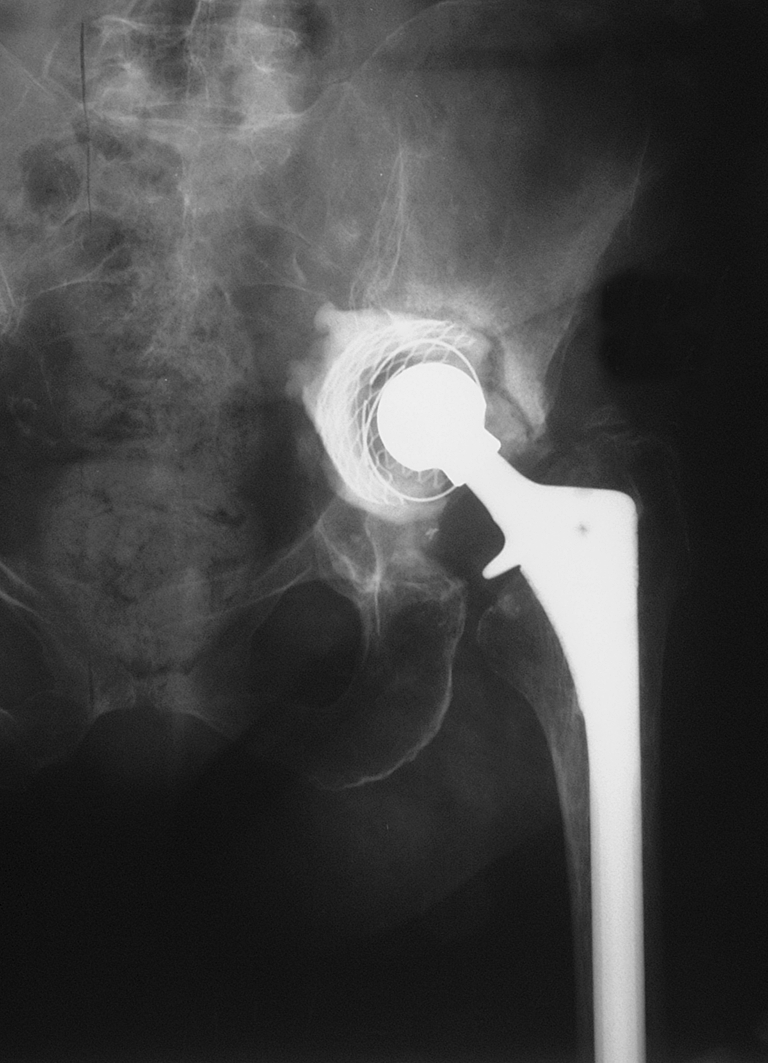

Fig. 3.

X-ray 1 1/2 year postop. Bone graft is incorporated; no signs of mechanical failure

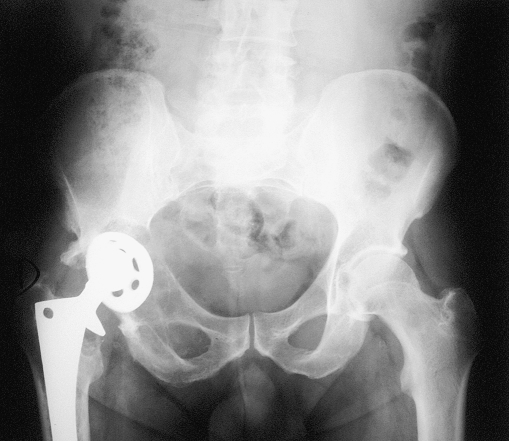

Fig. 4.

Massive osteolysis

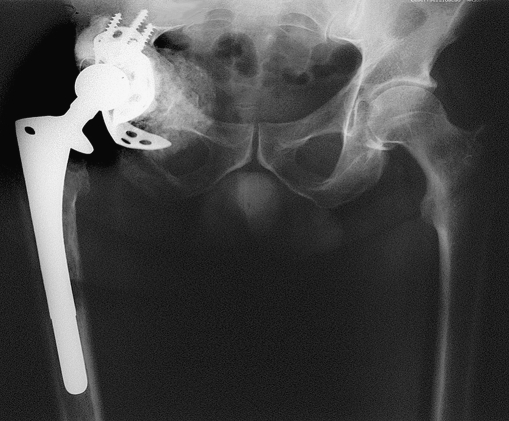

Fig. 5.

After debridement, there was no integrity of the columns

Fig. 6.

Post-op control with a vertical cage partially corrected with the position of the liner

In addition to the difficulty in identifying and interpreting these lesions, the different classification systems used pose a significant problem [1, 15, 16]. Prognosis and treatment options vary in the presence of mild, moderate, or severe bone loss and with undiagnosed stress or intraoperative iatrogenic fractures leading to a pelvic dissociation [17]. Classification systems have limited prognostic value, leaving surgeons with the responsibility of tailoring treatment according to intraoperative findings [9, 18]. An iatrogenic fracture or bone loss, stress fracture, or misdiagnosed pelvic discontinuity may lead to the early failure of an initially well-planned acetabular reconstruction [12, 17].

The most frequently used radiological classifications for acetabular defects are those defined by D’Antonio (AAOS) [15], Paprosky [18], and Gross [19]. The Paprosky classification quantifies the extent of bone loss to guide clinical decision making, but it does not specifically include a pelvic discontinuity category.

The AAOS and Gross classifications are more descriptive of the type and location of the bone loss and have been modified to quantify the extent of bone loss. These two classifications include a category for pelvic discontinuity.

Berry [2] subclassified the AAOS type IV defects into three categories: type IVa (pelvic discontinuity with cavitary or moderate segmental bone loss), type IVb (severe segmental loss or combined segmental and massive cavitary bone loss), and type IVc (previously irradiated bone with or without cavitary or segmental bone loss) [2, 20].

Possible solutions for this problem may be to always use Berry’s classification when describing a pelvic dissociation or simply subclassify Paprosky’s classification defects into those with or without pelvic discontinuity (for example, type III A or type III B with or without discontinuity). Few reports compare treatment options and results for the different subcategories of pelvic discontinuities, thus making it even more difficult to agree on a treatment protocol for each of these acetabular defects.

Postoperative evaluation

Gill [8] classified the incorporation or resorption of the graft and mechanical failure in cases with massive acetabular defects into three types:

Possible loosening or type I: nonprogressive radiolucent line and no involvement of the screws.

Probable loosening or type II: progressive radiolucent medial and superior line.

Definitive loosening or type III: broken screws, migration greater than 5 mm, and complete progressive radiolucent medial and superior line through the screws. Significant migration is defined by Gill as being greater than 3 mm. Other authors considered a relevant migration as the rotation of the acetabular shell by 5° or more [13, 21].

In patients with pelvic discontinuity, Berry [2] considers the discontinuity to be:

Definitively healed if bridging callus or trabecular bone is visible throughout the site of the discontinuity.

Possibly healed if there are no indirect signs of nonunion, such as failure of the construction.

Unhealed if it is still visible or if there are signs of failure of the implant.

Clinically, the result is considered satisfactory if the patient is able to walk independently without significant pain, the construction is possibly or definitively healed according to the radiographs, and the acetabulum does not require further surgery.

Because of the complexity of treatment, some authors distinguish between reoperation (nonrelated prosthetic replacement complications) and revision of the reconstruction (because of mechanical failure of the implant or graft) [22].

Surgical treatment options

Pelvic discontinuity or dissociation is a very specific problem within the field of hip revision arthroplasty procedures. However, few studies address this entity and most authors report a miscellany of acetabular defects (including some cases of pelvic discontinuity) and present different solutions and techniques, thus making comparison almost impossible (reported series are summarized in Table 1).

Table 1.

Review of the literature

| Series | No. discontinuities/total of the series | Type of reconstruction | Supplementary reconstruction | Healed | Follow-up | Harris/if other specified | Complications | Specifications of the graft | Failures |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sporer and Paprosky [41] | 13 cases | Trabecular metal cage in distraction | No | 12 | 2.6 years | 41 preop to 87 postop | 1 infection | 1 case | |

| Springer et al. [27] | 7 late stress fracture 8 months post-op, 5 operated | Trabecular metal cup+cancellous allograft+BDM | 4 cases supplementary plating, 1 case cup cage, no cup revision | 6 | 18 months | – | 2 plate breakage | Cancellous allograft+B. Demineralized matrix | 1 case |

| Mahoney and Garvin [26] | 1 | Late stress fracture | Double plating | 1 | 27 months | – | Failure 2 reoperations | Autogenous iliac crest | 2 reoperations healed |

| Ko et al. [33] | 2 | Intraoperative fracture | Burch–Schneider+morselized cancellous allograft | 2 | 24 and 32 months | 91 and 94 points | No | Not specified | 0 |

| Peters et al. [13] | (15/63) | Modular cage. Porous coating | Morselized cancellous allograft and autograft, 5 hips bulk structural allograft | NSPD | 29 months | 70–80 points; 39 average improvement, only 10% were pain free | 13% reoperation rate, unsolved dislocations | Fem. heads and distal femur | 8% mechanical failures, NSPD |

| Holt and Dennis [11] | (3/26) | Custom triflanged cage | 1 out of 3 PD additional plating, morselized allograft | 1/3 | 54 months | 39 preop to 78, NSPD | 2 failures, ischial disengagement and screw loosening | 2 failures before 18 months | |

| Lietman and Bhawnani [32] | 11 | Partial pelvic cup cage | Morselized allograft, demineralized bone matrix. Cement in tumors | 5 months | – | 1 nerve palsy, 1 infection-suppression therapy | 0 | ||

| Christie et al. [38] | (39/78) | Custom triflange cage | No. Morselized allograft | 37 | 53 months | From 33 preop to 82 postop, not specified for PD | 22%, 17% dislocations, 5% nerve injuries | 5.5%, ischial screws loosening | |

| Berry et al. [2] | 27 | 13 BS, 7 posterior plate, 7 double plating | 7 structural grafts without cage, 2 more with cage | 20 | 3 years | 60% satisfactory result. Own criteria | 4 recurrent dislocation, 1 infection | Fresh-frozen allograft, autograft | 4 failures (allografts without cages) |

| Kerboull et al. [31] | (12/60) | Kerboull cage | Femoral head bulk allografts | 12 | 10 years | Merle d’Aubigné 17 (11 preop), NSPD | No migrations, all grafts consolidated, late resorptions | Sterilely harvested and fresh-frozen | One case recaged 6 years postop |

| Stiehl et al. [20] | (10/17), 9 type IVb and 1 type IVc | No cage, 8 double plating | Structural allograft, 7 pelvic acetabular transplants, 3 femoral heads | 8 | 7 years, 3 deaths | 70 | 3 Girdlestone, infection, 3 dislocation, 1 sciatic palsy | 60%, 6 out of 10 rerevised | |

| Jasty [5] | (1/19) | Jumbo cup | Morselized allograft | 0 | ¿?, 10 years the entire series | Not reported | Aseptic loosening and non union of the graft | Fresh-frozen | Failure |

| Harris [3] | (2 out of 46) | Porous cup, high hip center | Morselized allograft | 2 | 10 years | Not reported | Not detailed | No | |

| Gerber 2003 | (2 out of 61) | Ganz ring | Morselized and bulk allograft | 0 | 13 and 30 months | Not reported | 1 Girdlestone, 1 BS cage. Not detailed | ¿? | Failure, 1 Girdlestone, 1 BS cage |

| Koster et al. [7] | (4 out of 104) | LOR cup | Morselized autograft and allograft | ¿2? | 3.6 years | 51 preop to 82 postop. NSPD | 1 aseptic loosening | 2 migrations | |

| Böstrom et al. [36] | 6 out of 31 | Contour cage plus morselized allograft | Two cases an additional plate | 3 | 30 months | 80 points, NSPD | 50% failures | Fresh-frozen, freeze-dried, and Grafton | Mechanical failures |

| Goodman et al. [10] and Gross and Goodman [43] | 10 out of 61 | Antiprotrusio cage (4 BS, 1 CC), no plating | Corticocancellous structural allograft | 8 | 3.3 years | Not reported | Dislocations, 1 Girdlestone for infected type IVc defect | Fresh-frozen and irradiated | 50% failures, loosening or broken flanges 3 |

| Eggli et al. [24] | 7 | Ganz ring, 3 anterior plating, 4 anterior and posterior plating | Morselized auto and allograft | 7 | 8 years | 33 preop to 73 postop, Merle d’Aubigné from 7.5 to 13.2 | 1 cup loosening after 12 months, 1 loose screw removed | Autogenous iliac crest+morselized allograft? | 1 partial ischial nerve palsy, 1 recurrent dislocation |

| Winter et al. [46] | 4 out of 38 | Burch–Schneider | Morselized allograft, femoral heads | 4 | 7.3 years | 82.6 | No | Fresh-frozen | No |

| Paprosky et al. [37] | 16 | Cages+11 plates+7 structural allografts | 7 structural allografts+plate, 6 cancellous–plating | 5 years | Merle from 3.7 to 6.8 postop for pain and walking | 1 sepsis, 4 nerve palsies, 1 dislocation | 4 revisions, 3+loose, 1 resection | ||

| Van Haaren et al. [54] | 6 | Meshes impaction grafting | Fresh-frozen allograft | 1 | 7 years | Not reported | Not specified | Fresh-frozen | Most early failures |

Second column, in parentheses, the number of patients with pelvic discontinuity included in series with massive acetabular bone loss (for example, 2 out of 61). Grafton (demineralized cortical bone and glycerol; Osteotech, Schrewsbury, NJ, USA).

The principles of treatment of pelvic dissociation are as follows [12, 23]:

Identification of the problem.

Adequate restoration of bone loss.

Mechanical stabilization of pelvic discontinuity.

Placement of a stable acetabular component and reconstitution of hip biomechanics.

Proposed solutions depend on the remaining bone stock and range from reconstruction with plates, grafts, and uncemented cups to massive structural allografts, cemented cups, and custom, modular, or standard cages with particulate or structural grafts.

Plating Plating may be limited to certain type IVa defects, to supplementing reconstruction with cages [2, 20, 24] in massive defects, or to late stress fractures in the presence of a well-fixed cup.

Stiehl et al. [20] combined the use of structural allografts and plating in ten cases with dissociation. In seven cases, a cemented cup was inserted in the allograft and in three cases, an uncemented cup was inserted. At 7 years, the survival of the reconstructions was 50% and the complication rate 60%. In the Mayo Clinic series [2], this treatment was successful in four type IVa cases and failed in the four type IVb cases.

Isolated plating can also be considered as one-stage or two-stage reconstruction surgery in which the fracture is stabilized before the acetabulum is revised [25, 26].

Springer et al. [27] have reported seven cases of pelvic discontinuity that were diagnosed several months after hip revision arthroplasty performed with tantalum cups. Rerevision surgery revealed the cups to be well-fixed in spite of the discontinuity, and supplementary fixation of the posterior column with a plate plus bone grafting was performed. Only four out of the seven cases healed.

Massive structural grafts These offer the theoretical advantages of restoration of bone stock and the rotation center of the hip, although they are now less commonly used for the treatment of acetabular bone loss because of a lack of universal availability, technical difficulties, and late biologic failures [28]. Some reports consider this technique excellent, especially in cases with defects affecting less than 50% of the acetabulum. These show a medium- to long-term success rate of 90% [9, 29]. However, when more than 50% of the cup is in direct contact with the graft, a higher failure rate is observed—45% at 7 years in the series of Garbuz et al. [9, 23] or 60% in the series of Sporer et al. [30]—thus making the use of a supporting ring in addition to the structural graft a more desirable option. The cage protects the structural allograft by providing pelvic stability and spanning the defect and by offloading the allograft until bone integration occurs. In spite of the theoretical advantages of structural allografts, the authors restricted normal weight bearing on the affected hip from 3 to 6 months [1, 10]. Very few groups have medium- or long-term experience with this type of reconstruction [1, 10, 31].

Noncustom reconstruction rings These are the most frequently used devices in cases with major periacetabular bone loss. Reconstruction rings are large metallic cages that gain purchase via multiple screws and flanges in the ilium and ischium [2, 24, 32]. Advantages are their relative affordable cost, availability, the possibility of restoring the hip rotation center, the mechanical support for the liner, and the protection they provide for the graft by transferring some of the load to distant remaining periacetabular bone. These reconstruction rings also have an inherent plate function in the case of iatrogenic fracture [33], massive bone loss, or pelvic discontinuity. A more important role is the protection the cage offers for the incorporation of the bone graft, which facilitates restoration of bone stock. Unfortunately, standard metallic cages lack a porous coating for bone ingrowth and their malleable flanges predispose the implant to failure. Their shapes and sizes are predetermined, which may sometimes prevent intimate contact with the remaining bone. The cages are made of thin, malleable metal so that the flanges can be bent and twisted during surgery to maximize contact with the remaining bone, but this flexibility precludes the application of coatings that allow biologic fixation, thus contributing to potential fatigue failure of the flanges and screws. Reports in the literature are neither numerous nor uniform and many do not provide functional results. They use different classifications and show a failure rate of between 0% and 25% in the medium-term because of ring migration or rupture, acetabular component loosening, or dislocation [13, 34, 35]. Implant failure and loss of fixation are the most common complications of currently available cages, as they are probably not rigid enough to act as plates in cases of massive bone loss, and fail unless the graft incorporates and protects the cage [32]. Neither the addition of a posterior plate, modifications in the design of these cages, nor use of bulk allografts seem to reduce complications, thus revealing that mechanical stability is only part of the problem [36, 37].

Custom triflanged cages These add to the advantages of “off the shelf” reconstruction cages the possibility of biologic fixation, better accommodation to the host bone defect, greater rigidity of the construct, and a greater variety of liners, thus increasing the likelihood of achieving better stability. These devices incorporate porous coating for bony ingrowth with potential long-term fixation through osseointegration. The disadvantages of these cages are their high cost, limited availability, impossibility of modifying the device during surgery, and the absence of long-term reports [11]. An additional disadvantage is that most bone loss is filled with metal instead of being restored with bone graft. The series of Christie et al. [38] is the largest in the literature and has the best results in terms of mechanical failure, although they report a complication rate of 25% and a reoperation rate of 8% because of dislocation. Other series with custom devices report a mechanical failure rate of 25% in the short-term, indicating that a more rigid device may not be the answer [39].

Cages with modular porous metal augments These allow both mechanical support for an uncemented hemispheric cup and bone ingrowth to improve long-term component fixation [12, 13]. Different defects can be addressed with these devices, which optimize contact with native bone. Some incorporate a variety of acetabular liner options, including a tripolar or constrained liner if additional hip stability is required.

With the use of new materials such as porous tantalum, a smaller contact surface with the host bone may be required and this may facilitate bone ingrowth, thus diminishing the need for bulk allografts and their associated complications [12]. This trabecular metal may be considered a better option for biological fixation because of its high volumetric porosity (70% to 80%) compared with chromium cobalt and titanium porous surfaces (30% to 50%), low modulus of elasticity (such as in subchondral bone) that allows for more physiologic load transfer, and high frictional characteristics (40% to 75% greater than standard porous coatings). These properties make it osteoconductive. It is biocompatible, has an excellent corrosion–erosion resistance, and theoretically causes less periprosthetic stress shielding. It can bear physiologic loads whereas bone ingrowth occurs within the trabeculae at higher percentages than other coatings. It can be used as a bulk implant, void filler, or porous coating. All these properties may reduce the limit of intimate contact between native bone and implant necessary to achieve biologic fixation to below 50%, which is the assumed threshold with conventional coatings [40].

Two theoretical disadvantages of modular metal cages are the interface of the augments to the hemispherical cup (potential for fretting or mechanical failure) and the limited bone stock restoration, as most of the defect is filled with the augments. An additional disadvantage may be the need for extremely difficult revision surgery.

Sporer and Paprosky [41] report 13 cases of pelvic discontinuity treated with a trabecular metal cage fitted with the pelvic dissociation in distraction when the defect is considered to be chronic and the potential for healing minimal. In 12 out of the 13 patients, the reconstruction was stable at 2.6 years. No additional plate fixation was used in these reconstructions. In spite of encouraging early results, there are no long-term reports with this technique. Hanssen and Lewallen recently described a new use of trabecular cups by which the tantalum cup bridges the acetabular defect and an antiprotrusio cage is placed over it spanning the pelvic discontinuity [42]. The same principle applies, i.e., the cage protects the bone ingrowth over the trabecular cup and later the bone protects the cage. The limit for protecting the trabecular cup with an antiprotrusio cage is when the contact surface with native bone is less than 50% [43].

Surgical complications and mechanical failures

None of the previously mentioned devices completely solve the three major problems in cases of pelvic discontinuity associated with massive bone loss: the high rate of complications, failure of the implant in the short- and long-term, and restoration of bone stock, which is intimately related to implant failure.

Despite several approaches and different devices, there remains a high incidence of complications (25–80%) [10, 24, 38], and some authors make the distinction between reoperation (caused by any complication) and revision (because of failure of the construction) [22]. The most frequent complications are those associated with any revision arthroplasty surgery, such as dislocation, nerve injury, and infection.

Dislocation is the most prevalent complication with rates ranging from 15% to 30%, leading some authors to routinely use constrained liners [9], whereas others propose using them in selected patients, such as those with severe abductor insufficiency because of nerve injury or extensive soft tissue scarring and damage, a deficient proximal femur, nonunion of the greater trochanter, or history of recurrent dislocation [21, 38]. It is not advisable to use them routinely, however, because this increases tensile stresses on the cage and, subsequently, in the graft and remaining native bone [10]. In the case of a greatly distorted anatomy, the need to replace bone stock can force restoration of the rotation center of the hip to a suboptimal position, which is usually proximal and lateral, leaving a leg-length discrepancy undercorrected. Sometimes the cage or polyethylene may be placed in a position that is too vertical or retroverted because of the extensive bone loss in the superior acetabulum or posterior column.

Extensive dissection of the proximal ilium can damage the superior gluteal nerve, leading to Trendelenburg gait. Ischial dissection may injure the sciatic nerve, and for this reason, some authors prefer not to place the inferior flange atop the ischium. However, slotting the cage into the ischium may diminish the resistance of the construct to mechanical traction or construct compression [8, 10]. In cases with severe ischial osteolysis, biologic cement can be introduced to improve the purchase gained by screws or an inferior flange on the ischium. The utility of slotting the flange as opposed to using screws remains unresolved.

The primary cause of sciatic nerve damage remains unclear and may result from a combination of factors, including extensive soft tissue dissection, inappropriate use of retractors, excessive lengthening of the limb [44], or thermal injury from cement polymerization.

Loss of fixation or implant failure This is the most specific and common complication of the current generation of acetabular rings. A balance between restoring massive bone loss with bone graft and achieving perfect contact between the cage and the native bone is crucial. Most pelvic cage failures are clearly visible on radiographs within the first year and a half of implantation. The typical pattern of failure is loosening of the ischial screws or disengagement of the ischial flange. This reflects the inability of the remaining bone to heal and support the mechanical loads required of it. Neither supplementary plating nor a bulk structural allograft allow for immediate weight bearing.

Most authors protect their constructs for 3 to 6 months, so the efforts of the surgeon must be directed toward achieving bone ingrowth and consolidation in the short-term in the hope that this will protect the cage from early mechanical failure. The weak link in all of these constructs is the bone graft in the early postoperative period and the metal shell later on [45]. Particulate bone grafts may have biological advantages over structural allografts and these have early mechanical advantages over morselized allografts. Radiography and histopathology show that remodeling of the morselized allograft is reliable provided that healing is adequately protected by the implant during the initial stages. If we consider pelvic dissociation a transacetabular pseudoarthrosis, the goal of the reconstruction procedure should be to provide for graft incorporation whereas achieving a sufficiently rigid fixation.

In an attempt to achieve a more rigid fixation, some authors favor the use of custom devices, but these are expensive and have limited availability. Some reports with these devices reveal a surprisingly high rate of success [38], whereas others show a mechanical failure rate of 25% [11, 39, 32]. Authors who use conventional cages and protect the hip from weight bearing have reported successful results for both massive defects and pelvic discontinuities [46].

Improved and faster graft healing would be of substantial clinical benefit in providing earlier biological and mechanical stability to the construct [44]. Trabecular metal cages could provide a more favorable environment for the remodeling of the graft, and these benefits should shorten the time of incorporation and protected weight bearing. The role of ceramics such as calcium phosphate or tricalcium phosphate, bone morphogenetic proteins, and growth factors that are intended to accelerate graft healing has yet to be demonstrated [47–50].

Restoration of bone stock

This is the main long-term goal for these patients. The biology of bone graft material in revision hip arthroplasty is not completely understood, and most studies of graft incorporation are based on radiographic data alone without histological support. Incorporation probably occurs later than suggested by radiographic guidelines. These findings may partially explain the short- to medium-term rates of mechanical failure (up to 35%) [17, 21, 48]. In most cases, however, no implant migration was observed.

Retrieved histologic samples show that massive cortical and corticocancellous structural grafts incorporate slowly, irregularly, and incompletely. The so-called radiographic signs of incorporation must not be fully interpreted as osseointegration. The incorporation process is confined to the outer few millimeters, leaving the more centrally located core permanently necrotic. This may lead to graft fracture and cage failure in the medium-term. Specific indications regarding the use of bulk structural allografts in acetabular revision remain elusive and controversial [51], although fresh-frozen and irradiated structural allograft constructs may offer better results than freeze-dried allografts. Cortical bone sterilized by gamma irradiation may have reduced biomechanical properties and bending and torsion strength, whereas cancellous bone seems to be less affected by sterilization. More important is the fact that allograft construct failures may occur more frequently because of late resorptions and implant allograft fixation failure than because of nonunion of the allograft [10, 31]. The mechanical strength of structural allografts is probably the main reason to use them in difficult reconstructions in an attempt to avoid early mechanical failures.

The biological advantages of particulate grafts, whether allograft or autograft, over structural grafts are well-documented [52, 53]. Impacted morselized cancellous allografts permit rapid vascular invasion and may, therefore, enable a faster, more uniform, and complete incorporation without mechanical weakening. Essential factors that influence the incorporation process are the stability of the graft, the amount of contact between host and graft, the stress patterns within the graft, and the vascularity of the host bed.

Fresh-frozen cancellous bone grafts are the most widely used and are well-documented, whereas experience with radiated bone or freeze-dried bone is limited. Reports with impaction grafting techniques for pelvic discontinuities are scarce but share a high failure rate [54]. The revascularization, incorporation, and remodeling of the morselized bone graft may have additional benefits, as it increases the contact surface between the implant and the bone, which decreases the forces on the implant and thus diminishes its tendency to fail [35]. Some reports indicate that the use of an acetabular reconstruction cage with morselized allograft is as reliable as a bulk allograft, but bone incorporation is more predictable [48].

Major disadvantages of preserved (frozen or freeze-dried) allografts are the absence of viable osteogenic cells and decreased osteoinductive factors. During the process of preservation by freezing, the antigenicity of the allograft is reduced, resulting in decreased host immune response and increasing potential graft incorporation. However, cells with osteogenic activity are destroyed [48]. It remains to be determined whether these disadvantages could be avoided by combinations of the grafts with bioactive proteins, stem cells, or new materials.

Conclusions

Treating a pelvic discontinuity involves the difficulty of simultaneously addressing a pelvic fracture and a hip revision arthroplasty in the setting of massive bone loss.

The treatment of pelvic discontinuities associated with failed total hip arthroplasty remains controversial, although some basic guidelines can be extracted from the literature.

In the presence of osteoporotic bone, massive bone loss, rheumatoid conditions, or irradiated bone, a pelvic dissociation must always be suspected when facing a revision arthroplasty.

A pelvic bone defect can be adequately staged using the AAOS and Gross classifications, supplemented with Berry’s subclassification for pelvic dissociations, as Paprosky’s very descriptive classification does not include specific staging for pelvic discontinuity.

Because of the complexity of this entity, in reviewing these patients, one should distinguish between reoperation resulting from any complication derived from surgery and revision because of failure of the reconstruction for both the implants and the grafts.

Healing of the discontinuity and restoration of bone stock remain the most important issues. To date, there is insufficient published data to establish clear guidelines on the best type of implant or allograft to be used.

Although antiprotrusio cages are the most commonly used implants, supplementing these with reconstruction plates and structural allografts has not improved results, indicating that the limiting factor may be biological rather than mechanical. Current generations of cages share the major problem of not providing biological fixation, which leads to failure in the medium- to long-term. Modifications in cage design, combinations of grafts, or associated fixation devices have not proven able to reduce complications or failures.

Trabecular metal cages may provide better biological fixation and a more favorable environment for bone grafting remodeling by reducing the use of structural grafts or custom implants and resolving different types of defects. If these goals can be partially or completely achieved, long-term stability of the construct, although as yet unknown, seems possible.

The mechanical strength of bulk structural allografts is probably the main reason for using them in difficult reconstructions. This is to avoid early mechanical failures, although specific indications regarding their use remain controversial, and failures have not been eliminated, even with the use of antiprotrusio cages and supplementary plating [36, 37].

New approaches to enhance biological incorporation of cages with osteoconductive materials (porous surfaces, tantalum, ceramics, calcium phosphate cement composites) and osteoinductive factors (recombinant bone morphogenetic proteins, demineralized bone matrices) combined with different types of grafts and bioactive factors (stem cells, platelet concentrates) are necessary to accelerate healing of bone deficiencies, prevent early implant mobilizations and subsidences, minimize complications, and improve long-term survival of the construct.

Acknowledgements

The authors sincerely thank Mr. Thomas O’Boyle and the Foundation for Biomedical Investigation of “Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón” for editorial assistance.

Abbreviations

- BS

Burch–Schneider cage

- CC

contour cup cage

- NSPD

not specified for pelvic discontinuity

Footnotes

Level of evidence. Level V. Expert Opinion.

Contributor Information

M. Villanueva, Email: mvillanuevam@yahoo.com.

A. Rios-Luna, Email: antonioriosluna@yahoo.es.

J. Pereiro De Lamo, Email: javier_pereiro@yahoo.com.

H. Fahandez-Saddi, Email: homidfsd@hotmail.com.

M. P.G. Böstrom, Email: bostromm@hss.edu.

References

- 1.O’Rourke MR, Paprosky WG, Rosemberg AG (2004) Use of structural allografts in acetabular revision surgery. Clin Orthop 420:113–121 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Berry DJ, Lewallen DG, Hanssen AD et al (1999) Pelvic discontinuity in revision total hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am 81:1692–1702 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Harris WH (1998) Reconstruction at a high hip center in acetabular revision surgery using a cementless acetabular component. Orthopedics 21:991–992 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Tanzer M (1998) Role and results of the high hip center. Orthop Clin North Am 29:241–247 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Jasty M (1998) Jumbo cups and morselized graft. Orthop Clin North Am 29:249–254 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.De Boer DK, Christie MJ (1998) Reconstruction of the deficient acetabulum with an oblong prosthesis: three to seven year results. J Arthroplasty 13:674–680 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Koster G, Willert HG, Kohler HP et al (1998) An oblong revision cup for large acetabular defects: design rationale and two to seven year follow up. J Arthroplasty 13:559–569 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Gill TJ, Sledge JB, Mueller ME (1998) The Burch–Schneider anti-protrusio cage in revision hip arthroplasty. Indications, principles and long-term results. J Bone Joint Surg Br 80:946–953 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Garbuz D, Mosri E, Mohammed N et al (1996) Classification and reconstruction in revision acetabular arthroplasty with bone stock deficiency. Clin Orthop 324:98–107 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Goodman S, Sastamoinen H, Shasha N et al (2004) Complications of ilio-ischial reconstructions rings in revision total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 19:436–446 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Holt GE, Dennis DA (2004) Use of custom triflanged acetabular components in revision total hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop 429:209–214 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Nehme A, Lewallen DG, Hanssen AD (2004) Modular porous metal augments for treatment of severe acetabular bone loss during revision hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop 429:201–208 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Peters CL, Miller M, Erickson J et al (2004) Acetabular revision with a modular anti-protrusio acetabular component. J Arthroplasty 19:67–72 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Chiang PP, Burke DW, Freiberg AA et al (2003) Osteolysis of the pelvis. Evaluation and treatment. Clin Orthop 417:164–174 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.D’Antonio JA, Capello WN, Borden LS et al (1989) Classification and management of acetabular abnormalities in total hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop 243:126–137 [PubMed]

- 16.Saleh KJ, Holtzman J, Gafni A et al (2001) Development, test reliability and validation of a classification for revision hip arthroplasty. J Orthop Res 19:50–56 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Saleh KJ, Jaroszynski G, Woodgate I et al (2000) Revision total hip arthroplasty with the use of structural acetabular allograft and reconstruction ring. A case series with a 10 year average follow-up. J Arthroplasty 15:951–958 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Paprosky WG, Perona PG, Lawrence JM (1994) Acetabular defect classification and surgical reconstruction in revision arthroplasty: a 6-year follow up evaluation. J Arthroplasty 9:33–44 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Gross AE (1999) Revision arthroplasty of the acetabulum with restoration of bone stock. Clin Orthop S369:198–207 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Stiehl JB, Saluja R, Diener T (2000) Reconstruction of major column defects and pelvic discontinuity in revision total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 15:849–857 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Udomkiat P, Dorr LD, Won YY et al (2001) Technical factors for success with metal ring acetabular reconstruction. J Arthroplasty 16:961–969 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Wachtl S, Jung M, Jakob R et al (2000) The Burch–Schneider antiprotrusio cage in acetabular revision surgery. A mean follow-up of 12 years. J Arthroplasty 15:959–963 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Gross AE, Goodman S (2004) The current role of structural grafts and cages in revision arthroplasty of the hip. Clin Orthop 429:193–200 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Eggli S, Muller C, Ganz R (2002) Revision surgery in pelvic discontinuity. An analysis of seven patients. Clin Orthop 398:136–145 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Murphy SB (2005) Management of acetabular bone stock deficiency. J Arthroplasty 20(S2):85–90 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Mahoney CR, Garvin KL (2002) Periprosthetic acetabular stress fracture causing pelvis discontinuity. Orthopedics 25:83–85 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Springer BD, Berry DJ, Cabanela ME et al (2005) Early postoperative transverse pelvis fracture: a new complication related to revision arthroplasty with an uncemented cup. J Bone Joint Surg Am 87:2626–2632 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Scott MS, O’Rourke M, Chong P et al (2005) The use of structural distal femoral allografts for acetabular reconstruction. J Bone Joint Surg Am 87:760–765 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Shinar AA, Harris WH (1997) Bulk structural autogenous grafts and allografts for reconstruction of the acetabulum in total hip arthroplasty. Sixteen year average follow up. J Bone Joint Surg Am 79:159–168 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Sporer S, O’Rourke M, Paprosky W (2005) The treatment of pelvic discontinuity during acetabular revision. J Arthroplasty 20:79–84 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Kerboull M, Hamadouche M, Kerboull L (2000) The Kerboull acetabular reinforcement device in major acetabular reconstructions. Clin Orthop 378:155–168 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Lietman SA, Bhawnani K (2001) The partial pelvic replacement cup in severe acetabular defects. Orthopedics 24:1131–1135 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Ko PS, Chan WF, Wong MK et al (2004) Fixation using acetabular reconstruction cage and cancellous allografts for intraoperative acetabular fractures associated with cementless acetabular component insertion. J Arthroplasty 19:643–646 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Berry DJ (2004) Antiprotrusio cages for acetabular revision. Clin Orthop 420:106–112 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Shatzker J, Wong M (1999) Acetabular revision. The role of rings and cages. Clin Orthop 369:187–197 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Böstrom MP, Lehman AP, Buly RL, Lyman S et al (2006) Acetabular revision with the contour antiprotrusio cage, 2- to 5-year followup. Clin Orthop 453:188–194 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.Paprosky W, Sporer S, O’Rourke M (2006) The treatment of pelvic discontinuity with acetabular cages. Clin Orthop 453:183–187 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 38.Christie MJ, Barrington SA, Brinson MF et al (2001) Bridging massive acetabular defects with the triflanged cup: 2 to 9 years result. Clin Orthop 393:216–227 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 39.Joshi AB, Lee J, Christensen C (2002) Results for a custom acetabular component for acetabular deficiency. J Arthroplasty 17:643–648 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 40.Levine B, Della Valle C, Jacobs J (2006) Applications of porous tantalum in total hip arthroplasty. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 14:646–665 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 41.Sporer SM, Paprosky WG (2006) Acetabular revision using a trabecular metal acetabular component for severe acetabular bone loss associated with a pelvic discontinuity. J Arthroplasty 21:87–90 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 42.Hanssen AD, Lewallen DG (2004) Acetabular cages. A ladder across a melting pond. Orthopedics 27:830–32 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 43.Gross AE, Goodman SB (2005) Rebuilding the skeleton. The intraoperative use of trabecular metal in revision total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 20:91–93 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44.Nercessian OA (1999) Intraoperative complications. In: Steinberg ME, Garino JP (eds) Revision hip arthroplasty. Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins, Philadelphia, pp 443–456

- 45.Dennis DA (2003) Management of massive acetabular defects in revision total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 18:121–125 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 46.Winter E, Piert M, Volkmann R et al (2001) Allogeneic cancellous bone graft and a Bursch–Schneider ring for acetabular reconstruction in revision hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg 83A:862–867 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 47.Cook SD, Barrack RL, Shimmin A et al (2001) The use of osteogenic protein-1 in reconstructive surgery of the hip. J Arthroplasty 16:88–94 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 48.Gamradt SC, Lieberman JR (2003) Bone graft for revision hip arthroplasty. Biology and future applications. Clin Orthop 417:183–194 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 49.Speirs AD, Oxland TR, Masri BA et al (2005) Calcium phosphate cement composite in revision hip arthroplasty. Biomaterials 26:7310–7318 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 50.Kärrholm J, Hourigan P, Timperley J et al (2006) Mixing bone graft with OP-1 does not improve cup or stem fixation in revision surgery of the hip. 5-year follow-up of 10 acetabular and 11 femoral study cases and 40 control cases. Acta Orthop Scan 77:39–48 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 51.McDonald SJ, Mehin R. (2005) Acetabular revision: structural grafts. Advanced reconstruction. Hip. In Lieberman JR and Berry DJ (Ed) AAOS, pp 335–342

- 52.Slooff TJ, Gardeniers JW, Schreurs BW et al (1999) Acetabular bone grafting: impacted cancellous allografts. In: Steinberg ME, Garino JP (eds) Revision hip arthroplasty. Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins, Philadelphia, pp 249–261

- 53.Schreurs BW, Slooff TJ, Gardeniers JW et al (2001) Acetabular reconstruction with bone impaction grafting and a cemented cup. Clin Orthop 393:202–215 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 54.Van Haaren EH, Heyligers IC, Alexander FG, Wuisman PI (2007) High rate of failure of impaction grafting in large acetabular defects. J Bone Joint Surg Br 89(3):296–300 [DOI] [PubMed]