Summary

Objectives

To investigate tobacco use practices, beliefs and attitude among medical students in Syria.

Methods

This is a cross-sectional study among a random sample of 570 medical students (1st and 5th year) registered at Damascus Faculty of Medicine, 2006–07. We used a self-administered questionnaire inquiring about demographic information, smoking behaviour (cigarette, waterpipe), family and peer smoking, attitudes and beliefs about smoking and future role in advising patients to quit smoking.

Results

The overall prevalence of tobacco use was 10.9% for cigarette (15.8% men, 3.3% women), 23.5% for waterpipe (30.3% men, 13.4% women), and 7.3% for both (10.1% men, 3.1% women). Both smoking methods were more popular among 5th year students (15.4% and 27%) compared to their younger counterparts (6.6% and 19.7%). Regular smoking patterns predominated for cigarettes (62%), while occasional use patterns predominated for waterpipe (83%). More than two thirds of students (69%) think they may not or have difficulty addressing smoking in their future patients.

Conclusion

The level of tobacco use among Syrian medical students is alarming and point at the rapidly changing patterns towards waterpipe use, especially among female students. Medical schools should work harder to tackle this phenomenon and address it more efficiently in their curricula.

Keywords: Cigarette smoking, waterpipe smoking, medical students, prevalence, Syria

INTRODUCTION

Tobacco use is the leading preventable cause of death worldwide, and according to the latest estimates, more than 80% of the 8.3 million tobacco-attributable deaths in 2030 will occur in low-middle-income countries [1]. These shocking predictions highlight the need for developing nations to examine patterns and determinants of tobacco use, understand local tobacco use methods, develop effective cessation interventions, and train their own tobacco control scientists [2].

In many developing countries, including Syria, physicians represent an important asset in the fight against tobacco, owing to their respectability in the society as a credible source of health information [3]. Studies have shown repeatedly the positive role of physicians in influencing patients’ tobacco use, assisting in their smoking cessation efforts, and influencing national tobacco control policies [4–6]. This positive role is obviously hindered by physicians’ own tobacco use practices, which place their messages at conflict with their behaviour [7]. In Syria, cigarette smoking has reached 41% and 11% of men and women physicians, respectively, a testament of the seriousness of this problem [3].

Since tobacco use practices and beliefs about tobacco are formed early in life, it becomes interesting to look at the development of tobacco use among medical students, and how their education may have influenced their beliefs and practices. Evidence suggest that tobacco use remain widespread among medical student despite their better knowledge of involved risks [8, 9]. Obviously, this situation represents a missed opportunity and point at the inadequacy of tobacco control teaching in medical curricula. The recent emergence of waterpipe use in Syria and other Arab countries, and its associated claims of reduced harm represent a new threat for tobacco control efforts in this region. Today, boys and girls in the Arab world are increasingly using waterpipes, which they view as fashionable [10–12].

A recent study of tobacco use practices among university students in Syria showed worrisome trends with 23% of students smoking cigarettes and 15% of them smoking waterpipe [13]. Still there has been no study to document tobacco use practices, beliefs and attitude among medical students in this country. The importance of this knowledge to guide medical schools in Syria and the region about the adequacy of their tobacco control training and curricula was the main reason behind the conduction of this study.

METHODS

This cross-sectional study was carried out during 2006–07 among students at Damascus University School of Medicine, which is Syria’s largest medical school established more than 100 years ago in the capital, Damascus.

Study Design

The study cohort consisted of medical students in their 1st & 5th year registered at Damascus Faculty of Medicine, year 2006–2007. We thought that the 4 year interval between 1st and 5th years will give us information about the smoking trajectory at different ages and levels of medical knowledge among the study’s target group. We aimed to recruit about half of the students registered in these years totalling 1173 to have sufficient numbers for sex and smoking method-based comparisons. Accordingly, 612 students (364 men, 248 women: 320 1st-year, 292 5th-year) were randomly selected from the university register and were invited to participate in the survey. Students were approached during the clinical training sessions for 5th year students and the lab sessions for 1st year students. Among those 570 (93.1% response rate, M:F 340:230; 1st:5th Year 303:267) students agreed to participate and provided adequate responses for the analysis. An anonymous self-administered questionnaire was used after verbal informed consent according to the Review Committee of Damascus School of Medicine approved protocol.

Questionnaire

The questionnaire was developed in Arabic from relevant instruments used for the assessment of tobacco use including the Global Health Professionals Survey (GHPS), and the Global Youth Tobacco Survey (GYTS), in addition to previous questionnaires used in Syria for the assessment of waterpipe smoking [12, 14–16].

The questionnaire inquired about demographic details of participants, their smoking behaviour (cigarette, waterpipe), family and peer smoking, attitudes and beliefs about smoking and quitting, students’ role as future physicians in advising their patients to quit smoking, and finally students’ position about banning smoking in public places. Smokers in addition, were asked about their first smoking attempt, tobacco consumption (cigarettes per day, waterpipes per week), and their preferred cigarette brand.

Definitions

Smoking status was established in accordance to the WHO criteria for cigarette smoking and the criteria set by Maziak et al. for waterpipe smoking [16, 17]: smokers were subjects who, at the time of the survey, smoked either regularly (≥1 cigarette/day or ≥1 waterpipe/week) or occasionally (<1 cigarette a day or <1 waterpipe/week). Nonsmokers included subjects who, at the time of the survey, did not smoke. Those were categorized further into ex-smokers, who were formerly smokers but currently did not smoke, and never-smokers, who never smoked at all.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 13 software (SPSS; Chicago, IL). Continuous variables were presented as mean. Dichotomous variables were compared using the χ2 test, and continuous variables using the t-test (table 1). Univariate regression analysis was performed separately for cigarette and waterpipe to assess correlates of smoking among students. Variables showing association in the univariate analysis at p < 0.2 level were entered in 2 multivariate logistic regression models for cigarettes and waterpipe, separately. Adjusted odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) were reported for correlates of the outcome variable (current smoker, non-smoker). Tests were considered significant when the two-sided p value was < 0.05.

Table 1.

Patterns of use of tobacco among medical students in Damascus according to year of study at university (1st versus 5th)

| Tobacco Smoking % | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1st year n1=274 | 5th year n5=259 | Total N=533 | |

| Age (yrs): µ(SD) | 18.3(0.7) | 23.0 (0.9) | 20.5 (2.5) |

| Smoking Status | |||

| Cigarette Smokers | |||

| Occasional | 3.3 | 5.0 | 4.1 |

| Regular | 3.3 | 10.4* | 6.8 |

| Waterpipe Smokers | |||

| Occasional | 17.2 | 22.5 | 19.7 |

| Regular | 2.5 | 5.0 | 3.8 |

| Smokers of both cigarette & waterpipe | 5.1 | 9.8 | 7.3 |

| First smoking attempt | |||

| First cigarette | (n1=17) | (n5=40) | (n=57) |

| ≤9 yrs | 17.7 | 7.5 | 10.5 |

| 10–15 yrs | 17.7 | 7.5 | 10.5 |

| 16–18 yrs | 58.8 | 40.0 | 45.6 |

| ≥19 yrs | 5.6 | 45.0* | 33.4 |

| First waterpipe | (n1=53) | (n5=71) | (n=124) |

| ≤9 yrs | 7.6 | 0.0 | 3.2 |

| 10–15 yrs | 28.3 | 15.5 | 21.0 |

| 16–18 yrs | 60.4 | 29.6* | 42.7 |

| ≥19 yrs | 3.8 | 53.4* | 33.1 |

| Tobacco consumption by regular smokers µ(SD) | |||

| Cigarettes/day | 12.11(6.77) | 11.11(7.80) | 11.86(7.45) |

| Waterpipes/week | 3.7(3.0) | 5.4(5.6) | 4.8(4.8) |

p<0.05 for comparisons across year of study (1st versus 5th)

RESULTS

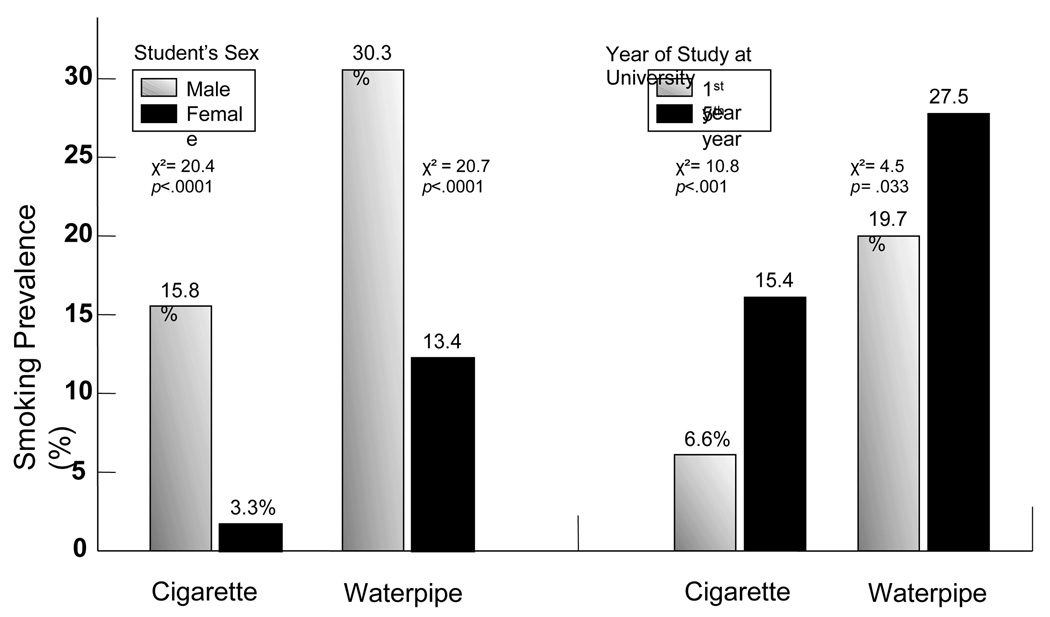

Of the 570 participants aged on average 20.5 (2.5) years, the overall prevalence of tobacco smoking was 10.9% for cigarette (15.8% men, 3.3% women), 23.5% for waterpipe (30.3% men, 13.4% women), and 7.3% for both (10.1% men, 3.1% women). The total prevalence of any type of smoking was 27.1% (36.0% men, 13.6% women). Cigarette smoking status among medical students differed substantially by sex, with current smoking being reported by 15.8% of men and 3.3% of women (χ2=20.4, p< .0001) (figure 1). Waterpipe use, was more popular among students but still higher in men (30.3%) compared to women students (13.4%) (χ2=20.7, p< .0001) (figure 1). Both smoking methods (cigarette & waterpipe) were more popular among 5th year students (15.4% and 27%) compared to their younger 1st year students (6.6% and 19.7%) (p<.001, p<.05 for cigarettes and waterpipe, respectively) (figure 1). Table 1 provides a detailed description of the study population according to their smoking status and year of study (1st versus 5th). Cigarette smoking was mostly a daily practice among smokers, while waterpipe smoking was mainly an occasional practice (Table 1). Analysis across all age groups showed that both ‘age of first cigarette’ and ‘age of first waterpipe’ were significantly different between students in their 1st and 5th year of study (X2=51.9, p<.0001; X2=57.8, p<.0001, respectively).

Figure 1.

Smoking prevalence according to sex and year at university stratified by method of smoking

Potential correlates of tobacco use among respondents were assessed in table 2. These include sex, age, year of study (1st versus 5th), use of other forms of tobacco (Table 2). In the multivariate logistic regression analysis, there same correlates were shown to be predictors of cigarette smoking, while only sex and use of other form of tobacco were predictors of waterpipe use (Table 3).

Table 2.

Correlates of smoking among medical students in Damascus, Syria

| Cigarette | Waterpipe | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Smokers %(n) | Nonsmokers %(n) | OR | 95% CI | Smokers %(n) | Nonsmokers %(n) | OR | 95% CI | |

| sex (men) | 5.44 | 2.42–12.23 | 2.82 | 1.78–4.46 | ||||

| Men | 15.8(51) | 84.2(272) | 30.3(97) | 69.7(223) | ||||

| Women | 3.3(7) | 96.7(203) | 13.4(29) | 86.6(188) | ||||

| Year at university (5th Year vs. 1st) | 2.60 | 1.45–4.66 | 1.55 | 1.03–2.31 | ||||

| 1st Year | 6.6(18) | 93.4(256) | 19.7(55) | 80.3(224) | ||||

| 5th Year | 15.4(40) | 84.6(219) | 27.5(71) | 72.5(187) | ||||

| Parent(s) smoker | 38.6(22) | 40.2(191) | 0.88 | 0.49–1.54 | 19.5(23) | 17.3(66) | 1.16 | 0.68–1.96 |

| Sibling(s) smoker | 22.8(13) | 24.6(110) | 0.91 | 0.47–1.75 | 29.8(36) | 31.0(119) | 0.94 | 0.60–1.47 |

| Close friend(s) smoker | 52.3(23) | 45.6(188) | 1.31 | 0.70–2.43 | 62.6(67) | 64.2(228) | 0.93 | 0.60–1.46 |

| Smoking other forms of tobacco | 73.2(41) | 17.9(81) | 12.52 | 6.61–23.70 | 33.6(41) | 3.9(15) | 12.52 | 6.61–23.71 |

| Age µ(SD) | 21.5(2.3) | 20.4(2.5) | 1.21* | 1.07–1.35 | 21.0(2.5) | 20.4(2.5) | 1.10 | 1.02–1.19 |

increment of 1 year in age

Table 3.

Multivariate logistic regression analysis for predictors of tobacco use among medical students in Damascus, Syria

| OR* | 95% CI | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||

| Waterpipe smoker | 10.10 | 5.24 | 19.47 | |

| Sex (men) | 3.99 | 1.68 | 9.50 | |

| Year (5th)* | 2.75 | 1.42 | 5.33 | |

| Age (yrs) | 1.21 | 1.06 | 1.39 | |

| Cigarette Smoker | 10.34 | 5.40 | 19.78 | |

| Sex (men) | 2.36 | 1.43 | 3.91 | |

because of multi-colinearity, year at university and age were entered in the models separately.

As for students’ attitudes and beliefs regarding smoking, more than 90% of the respondents supported banning of smoking in public places with no difference between smokers and nonsmokers (Table 4). Another interesting finding was the clear difference in attitude towards male and female smokers, as almost half the respondents think that male smokers look less attractive, compared to 80% who think that female smokers look less attractive (table 4). Another interesting point is that about three quarters of the respondents considered waterpipe to be more harmful than cigarettes with no significant difference between smokers and nonsmokers of either type (Table 4). Smokers’ attitude towards quitting showed that about half of students thought that quitting cigarettes or waterpipe will be difficult with no difference according to smoking status. Generally, cigarette smokers in our population favoured foreign brands (61%), while only 7% favoured local brands, and 32% had no preference.

Table 4.

Beliefs & attitudes towards tobacco use among medical students in Damascus, Syria

| Cigarette | Waterpipe | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Smokers %(n) | Nonsmokers %(n) | Smokers %(n) | Nonsmokers %(n) | |

| Q1: Should smoking be banned in public places? “Yes” | 94.8(55) | 90.5(420) | 91.7(111) | 91.1(368) |

| Q2: Will you advise patients in the future to quit smoking? | ||||

| Yes, in a total objective way | 42.9(24) | 30.6(141) | 34.2(41) | 30.3(122) |

| Sometimes, but it will not be easy | 42.9(24) | 51.0 (235) | 49.1(59) | 51.2(206) |

| No, I will not | 14.2(8) | 18.4 (85) | 16.7(20) | 18.5(74) |

| Q3: Do you think quitting smoking is difficult? | 50.9(29) | 53.8(238) | 56.7(68) | 52.9(202) |

| Q4 Do you think smoking cigarettes is religiously unacceptable? | 52.7(29) | 55.4(253) | N/A | N/A |

| Q5: Do you think smoking waterpipe is religiously unacceptable? | N/A | N/A | 67.3(74) | 62.9(234) |

| Q6: Do you think a male smoker looks: | ||||

| More attractive | 1.8(1) | 7.8(36) | 5.8(7) | 8.7(35) |

| Less attractive | 56.1(32) | 51.0(235) | 52.1(63) | 51.4(206) |

| The same | 42.1(24) | 41.2(190) | 42.1(51) | 39.9(160) |

| Q7: Do you think a female smoker looks: | ||||

| More attractive | 1 (1.7) | 6.3(29) | 5.7(7) | 6.5(26) |

| Less attractive | 52 (89.7) | 78.6(361)* | 85.2(104) | 79.2(316)* |

| The same | 5 (8.6) | 15.1(69)* | 9.1(11) | 14.3(57)* |

| Q8: Which do you consider more harmful, cigarette or waterpipe? | ||||

| No difference | 2.2(1) | 17.1(73) | 13.2(14) | 17.3(64) |

| Waterpipe is worse | 84.8(39) | 74.2(317) | 76.4(81) | 74.3(274) |

| Cigarette is worse | 13.0(6) | 7.5(32) | 9.4(10) | 7.6(28) |

| Waterpipe is not harmful | 0.0 (0) | 1.2(5) | 1.0(1) | 0.8(3) |

p < 0.05 for comparisons across smoking status for each tobacco use method

DISCUSSION

This study about the smoking habits of medical students in one of the major universities in Syria presents unique data about this key population for future health promotion in this country. It shows widespread smoking among medical students affecting about third of them in different forms. As noted before in Syria and other Arab societies, the gender-related pattern in tobacco use was evident in this study, with men more likely to smoke cigarettes as well as waterpipes. Likewise, the previously noted predominance of intermittent use pattern of waterpipe compared to the more regular use pattern of cigarettes [18] was observed in this study. This is likely due to the social nature of waterpipe use and the accessibility, time and setting differences between the two tobacco use methods [18].

Still, the predominance of waterpipe use among our study’s population was an unexpected finding, since previous studies of tobacco use among university students in Syria showed a predominance of cigarettes smoking [13]. We are not sure whether this phenomenon represents a unique feature to this health-educated group or is a reflection of the rapidly changing dynamics of the smoking epidemic among youth in Syria and other Arab societies. We favour the second explanation, since more students in our study said that they think waterpipe is more harmful than cigarettes, and their belief was not affected by their waterpipe or cigarette smoking behaviour. In addition, the age-tobacco use dynamics differed between the two tobacco use methods, and between waterpipe users in different grades showing an ever-changing picture and an increasing uptake of waterpipes. This is likely reflection of an epidemic in progress, whereby stable age-tobacco use patterns have not been reached yet.

The men-women ratio of cigarette smoking and waterpipe smoking among this group is also interesting. So while cigarette smoking was more than five times as common among male students compared to female students - a pattern compatible with the unfavourable perception of women smoking in the Syrian and Arab societies [19] - the men-women ratio for waterpipe use was a little more than two. This shows that a more tolerant attitude toward women waterpipe smoking can be one of the factors fuelling the spread of this tobacco use method among women in Arabic and traditional societies [18]. This argument is supported by data from neighbouring Lebanon and other Arab countries showing increasingly less sex-based gradient in waterpipe use compared to cigarettes [20–22]. It is likely that since waterpipe has a long standing association with the Orient and the Middle East, it is perceived by the local populations as more conforming to the local traditions, and thus more acceptable to be used by women than the “Western” cigarettes [18]. Another evidence in support of this argument is the huge difference between cigarette and waterpipe smoking observed among female students in our study, whereby waterpipe use was about four times as common as cigarette smoking amongst them. This is likely to reflect a changing dynamics among youths in Syria, as our previous study among university students was not able to show this sex-tobacco use method preference pattern [13].

Generally, cigarette smoking proportions among our medical students (10.9%) were lower than those reported among medical students of neighbouring countries; 29% in Saudi Arabia [23], 14.4% in Pakistan [24] and 18.5% in Iran [25]. This, however, should be cautiously interpreted as these studies were computed at different times in an area where smoking rates may be rapidly changing. Besides, medical students smoking habit (10.9%) was below the level found among university students in Syria (18.6%)[13]. This may look as an indicator of a more pro-health attitude among medical students. As we mentioned earlier however, what argues against this explanation are the high proportions of waterpipe use among medical students despite their belief that waterpipe is more harmful than cigarettes. These observations point at the possibility of waterpipe smoking spreading rapidly among educated youths in Syria, and in many cases replacing cigarette smoking among them, as smoking both methods was not common.

A particularly discouraging finding is that more than two thirds of students believe that they will either not discus quitting tobacco use with their future patients or it will be hard for them to do so. This attitude did not differ much across the smoking trajectory of students, which points at a major inadequacy of addressing this issue during medical school education.

Unfortunately, there is no current policy adopted by Syrian medical schools to tackle the surge of tobacco consumption among students. Although by the end of their medical training students have a reasonably good knowledge of the association between smoking and different diseases, there is still a steady increase in smoking proportions among students as progressing through their medical course. This finding is, indeed, alarming and shows failure of the medical school curriculum to invoke health conscious behaviours and attitudes among future physicians and health educators.

The medical school should consider providing greater education about the myths and hazards of tobacco consumption and introducing a course of smoking-cessation counselling skills into the curriculum. This preventative anti-smoking measures must be implemented from the first year of medical education. Otherwise, an entrenched smoking culture may remain among the student demographic and thus jeopardise their future role as physicians responsible for tobacco control programmes.

Another key component is to make the medical school buildings, including dormitories and cafeterias, smoke-free. This policy protects nonsmokers from passive smoke exposure. It also limits the visibility and accessibility of tobacco products and may discourage initiation, help keeping occasional smokers from becoming regular users and boost the success of smokers who are trying to quit [26]. Secondly, there need to be a stronger focus on positive youth development during the transition from youth into adulthood [27]. This issue could be incorporated into medical education to help students as they progress through their course and mature from undergraduate students into young doctors.

On a national level, policy makers should also be alerted to the tobacco in general and the new merge of waterpipe in specific which is so far escaping current regulations and restrictions imposed on cigarettes, such as the ban on advertisement and the inclusion of health warnings on tobacco products.

CONCLUSIONS

Despite the limitations of cross sectional surveys and self-report, the current study provides pioneer information about the smoking practices and beliefs among this important group for the future of public health in Syria. It shows widespread smoking especially among men, and a rapidly changing pattern towards waterpipe use, especially among female students. It also points at the failure of the medical education to invoke healthy behaviours and attitudes towards the number 1 cause of ill health and mortality worldwide. Future studies should look more into the tobacco use practices and beliefs of faculty, curriculum components addressing smoking, smoking policies within the university, and how these factors reflect on to the practices and attitudes of student. The widespread waterpipe use among students despite their awareness of its detrimental aspects should be a whistleblower to health authorities in Syria and the Arab world about this eminent epidemic.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

We would like to thank the participating investigators: Mohamad Kheir Hasoun, Lubna Kharseh, Rawan Qatramiz, Hisham Jaber, Waseem Alfahel, Belal Firwana, Ahmad Al-moujahed and Osama Altayar for their help in collecting the data and building the spreadsheets. We would also like to acknowledge Dr. Lilian Dayrani for her valuable feedback on the questionnaire format. Dr. Maziak and the Syrian Centre for Tobacco Studies are supported by NIDA grant (R01 DA024876-01).

REFERENCES

- 1.Mathers CD, Loncar D. Projection of global mortality and burden of disease from 2002 to 2030. PLoS Med. 2006;3(11):e442. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maziak W, Arora M, Reddy KS, Mao Z. On the gains of seeding tobacco research in developing countries. Tob Control. 2006;15(Suppl 1):i3–i4. doi: 10.1136/tc.2005.014464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maziak W, Mzayek F, Asfar T, Hassig SE. Smoking among physicians in Syria: Do as I say, not as I do! Ann Saudi Med. 1999;19(3):253–256. doi: 10.5144/0256-4947.1999.253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davis RM. When doctors smoke. Tob Control. 1993;2(3):187–188. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gilpin EA, Pierce JP, Johnson M, Bal D. Physician advice to quit smoking: results from the 1990 California Tobacco Survey. J Gen Intern Med. 1993;8(10):549–553. doi: 10.1007/BF02599637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Paul CL, Sanson-Fisher RW. Experts' agreement on the relative effectiveness of 29 smoking reduction strategies. Prev Med. 1996;25(5):517–526. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1996.0085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kawakami M, Nakamura S, Fumimoto H, Takizawa J, Baba M. Relation between smoking status of physicians and their enthusiasm to offer smoking cessation advice. Intern Med. 1997;36(3):162–165. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.36.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Flaherty JA, Richman JA. Substance use and addiction among medical students, residents, and physicians. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 1993;16(1):189–197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Richmond R. Teaching medical students about tobacco. Thorax. 1999;54(1):70–78. doi: 10.1136/thx.54.1.70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tamim H, Terro A, Kassem H, Ghazi A, Khamis TA, Hay MM, Musharrafieh U. Tobacco use by university students, Lebanon, 2001. Addiction. 2003;98(7):933–939. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2003.00413.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Varsano S, Ganz I, Eldor N, Garenkin M. Water-pipe tobacco smoking among school children in Israel: frequencies, habits and attitudes. Harefuah. 2003;142(11):736–741. 807. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maziak W, Fouad MF, Asfar T, Hammal F, Bachir EM, Rastam S, Eissenberg T, Ward KD. Prevalence and characteristics of narghile smoking among university students in Syria. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2004;8(7):882–889. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maziak W, Hammal F, Rastam S, Asfar T, Eissenberg T, Bachir ME, Fouad MF, Ward KD. Characteristics of cigarette smoking and quitting among university students in Syria. Prev Med. 2004;39(2):330–336. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. [accessed 23rd Aug 2006.];The Global Youth Tobacco Survey (GYTS), Tobacco Free Initiative (TFI) Online http://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/Global/GYTS/questionnaire.htm.

- 15. [accessed 23rd Aug 2006];The Global Health Professional Survey (GHPS), Tobacco Free Initiative (TFI) Online: http://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/Global/GHPS/questions.htm.

- 16.Maziak W, Ward KD, Afifi Soweid RA, Eissenberg T. Standardizing questionnaire items for the assessment of waterpipe tobacco use in epidemiological studies. Public Health. 2005;119(5):400–404. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2004.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.WHO. Geneva: WHO; Guidelines for controlling and monitoring the tobacco epidemic. 1998

- 18.Maziak W, Eissenberg T, Ward KD. Patterns of waterpipe use and dependence: implication for intervention development. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2005;80(1):173–179. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2004.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maziak W. Smoking in Syria: profile of a developing Arab country. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2002;6(3):183–191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maziak W, Ward KD, Eissenberg T. Interventions for waterpipe smoking cessation. Coch Database Syst Rev. 2007;(4):CD005549. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005549.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tamim H, Al-Sahab B, Akkary G, Ghanem M, Tamim N, El Roueiheb Z, Kanj M, Afifi R. Cigarette and nargileh smoking practices among school students in Beirut, Lebanon. Am J Health Behav. 2007;31(1):56–63. doi: 10.5555/ajhb.2007.31.1.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Warren CW, Jones NR, Eriksen MP, Asma S Global Tobacco Surveillance System (GTSS) collaborative group. Patterns of global tobacco use in young people and implications for future chronic disease burden in adults. Lancet. 2006;367(9512):749–753. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68192-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hashim TJ. Smoking habits of students in College of Applied Medical Science, Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med J. 2000;21(1):76–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Khan FM, Husain SJ, Laeeq A, Awais A, Hussain SF, Khan JA. Smoking prevalence, knowledge and attitudes among medical students in Karachi, Pakistan. East Mediterr Health J. 2005;11(5–6):952–958. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ahmadi J, Khalili H, Jooybar R, Namazi N, Aghaei PM. Cigarette smoking among Iranian medical students, resident physicians and attending physicians. Eur J Med Res. 2001;6(9):406–408. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fichtenberg CM, Glantz SA. Effect of smoke-free workplaces on smoking behaviour: systematic review. BMJ. 2002;325(7357):188. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7357.188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.WHO. Geneva: World Health Organisation; What in the World Works? International Consultation on Tobacco and Youth: Final Conference Report. 2000