Abstract

Lupoid leishmaniasis is a unique form of cutaneous leishmaniasis characterized by unusual clinical features and a chronic relapsing course, mostly caused by infection with Leishmania tropica. In this clinical form, 1-2 yr after healing of the acute lesion, new papules and nodules appear at the margin of the remaining scar. Herein, we describe a case of this clinical form that was resistant to 2 courses of treatments: systemic glucantime and then a combination therapy with allopurinol and systemic glucantime. However, marked improvement was seen after a combination therapy with topical trichloroacetic acid solution (50%) and systemic glucantime, and there were no signs of recurrence after 1 yr of follow-up.

Keywords: Leishmanis tropica, cutaneous leishmaniasis, trichloroacetic acid

INTRODUCTION

Leishmaniasis currently threatens 350 million people in 88 countries around the world. Up to 90% of cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL) cases occur in Afghanistan, Brazil, Iran, Peru, Saudi Arabia, and Syria. Lesions can be very disfiguring, particularly on the face, which may have long-term psychological and social consequences [1]. Lupoid leishmaniasis is a clinical form that was described in 1923 [2], and it is a chronic condition that typically follows acute cutaneous leishmaniasis infection. One to 2 yr after healing of the acute lesion, new papules and nodules will appear at the margin of the remaining scar [3]. The papules have a glaucomatous appearance and are often scaly. Most reported cases were associated with old world strains of leishmaniasis rather than new world strains, and Leishmania tropica was the responsible agent in their majority [3]. The incidence of lupoid leishmaniasis reported in previous studies ranges from 0.5-6.2% [4,5].

Lupoid CL is prevalent in the endemic area of leishmaniasis, particularly in the Middle East and Afghanistan [4]. Histological features of this condition include well-organized epithelioid granuloma surrounded by lymphocytes, the absence of amastigotes, and frequent negative cultures for leishmaniasis [5]. However, the leishmanin test is usually positive [6]. Herein, we describe a case of lupoid leishmaniasis that was resistant to systemic glucantime yet responded to a combination therapy with glucantime and topical application of trichloroacetic acid (TCA) solution.

CASE REPORT

A 19-yr-old Afghan man presented with a large atrophic scar on the nose, and there were some red infiltrative nodules at the margin of the lesion present for the last 3 yr (Fig. 1). At the beginning of the disease (3 yr ago), a direct smear was taken from the lesion and was positive for leishman bodies. The patient had been treated for CL with glucantime. The lesion improved, but it recurred after 1 yr. At the time of our visit, the patient's direct smear was negative for leishman bodies, and a histological examination indicated epidermal hyperplasia, severe infiltration of lymphoid plasma cells and epithelioid granuloma without caseous necrosis or leishman bodies, but the leishmanin test (Pasteur Institute, Tehran, Iran) was positive. The patient was treated with 2 courses of systemic glucantime (Aventis, Paris, France) at 20 mg/kg/day intramuscularly (IM) for 20 days and with a combination therapy of systemic glucantime (IM) at 20 mg/kg/day for 20 days plus allopurinol (Hakim, Tehran, Iran) at 20 mg/kg/day for 20 days, but relapse occurred after cessation of the treatment. We treated the patient with a combination therapy of topical TCA and systemic glucantime. After cleansing with alcohol, TCA (Merck, Berlin, Germany) (50% wt/vol) [7] was applied to the lesion using a cotton swab, and after frosting, the lesion was covered with vaseline (Fig. 2). There was no need to wash off any TCA from the lesion. TCA was applied once weekly for 3 wk. In addition, the patient was treated with systemic glucantime at 20 mg/kg/day for 20 days. The responses to the treatment were good, and the marginal nodules disappeared (Fig. 3). The patient was followed-up for 1 yr and showed no signs of recurrence.

Fig. 1.

Large atrophic scar (arrow) on the nose with red infiltrative nodules at the margin.

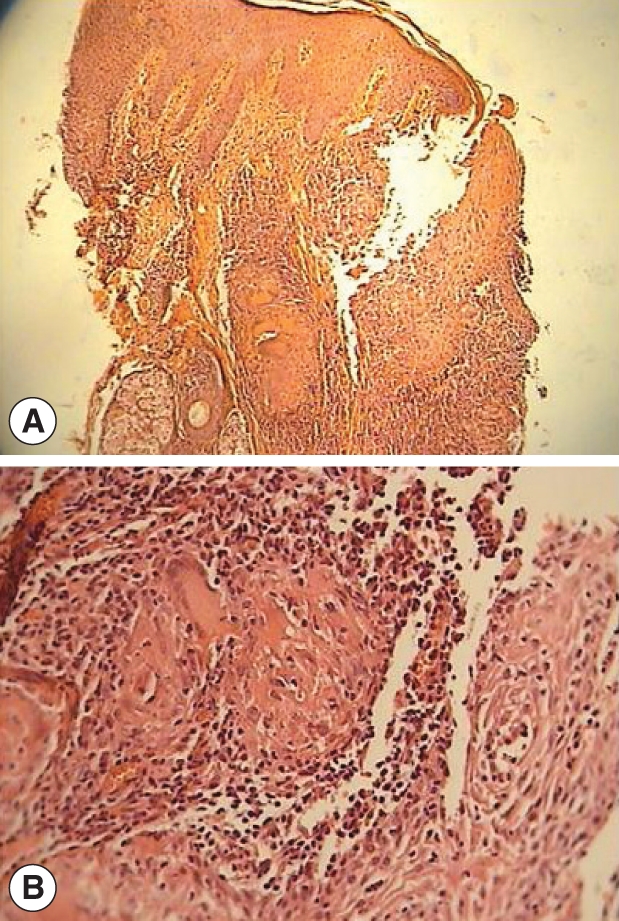

Fig. 2.

Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia of epidermis with small tuberculoid granuloma and mild to moderate mononuclear cell infiltrates (A ×40; B ×100).

Fig. 3.

Frosting the lesion after application of 50% TCA solution.

DISCUSSION

Clinically and histologically, lupoid leishmaniasis is similar to lupus vulgaris, which is the most important differential diagnostic consideration [8]. Differential diagnosis is difficult and may depend on detection of Leishmania amastigotes in the histological sections, growth of promastigotes in cultures, or identification of amastigotes by other techniques. This chronic condition typically follows acute CL, and in the majority of cases, Leishmania tropica is the causative agent [9].

There is no standard treatment for this condition, and multiple treatments have been reported with varying degrees of success [10]. Treatment options include intraregional pentavalent antimony [11], a combination therapy with intramuscular injection of meglumine antimoniate (MA) and allopurinol [12], local injection of amphothericin B [13], levamisole [14], dapsone [15], cryotherapy [16], and triple therapy with paromomycin, cryotherapy, and intralesional meglumine antimoniate [5].

In a previous study that was done in Isfahan, the efficacy of topical TCA (50%) in the treatment of CL was evaluated, and the response to the treatment was the same as the intraregional meglumine antimoniate [17]. TCA peeling has been used for the treatment of several skin lesions, including actinic degeneration and acne scarring. Its efficacy could be due to epidermal regeneration as well as to the regeneration of new collagen in the dermis.

Our patient, who was resistant to 2 courses of treatment with systemic glucantime and a combination therapy with glucantime and allopurinol showed marked improvement after a combination therapy with topical TCA (50%) and systemic glucantime. Additionally, there was no recurrence after 1 yr of follow-up. The good efficacy of TCA in the treatment of the above condition could be due, in part, to enhancing macrophage activity in addition to epidermal and collagen regeneration. We suggest that, in a randomized clinical trial, the efficacy of this combination treatment would be evaluated against systemic glucantime for the treatment of lupoid CL.

Fig. 4.

The patients after 1 yr of follow-up showing complete healing of the lesion.

References

- 1.Jones J, Bowling J, Watson J, Vega-Lopez F, White J, Higgins E. Old world cutaneous leishmaniasis infection in children: a case series. Arch Dis Child. 2005;90:530–531. doi: 10.1136/adc.2004.057968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Christopherson JB. Lupoid leishmaniasis; a leishmaniasis of the skin resembling lupus vulgaris; hitherto unclassified. Br J Dermatol. 1923;35:123–131. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Asilian A, Iraji F, Hedaiti HR, Siadat AH, Enshaieh S. Carbon dioxide laser for the treatment of lupoid cutaneous leishmaniasis (LCL): a case series of 24 patients. Dermatol Online J. 2006;12:3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gurel MS, Ulukanligil M, Ozbilge H. Cutaneous leishmaniasis in Sanliurfa: epidemiologic and clinical features of the last four years (1997-2000) Int J Dermatol. 2002;41:32–37. doi: 10.1046/j.0011-9059.2001.01396.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nilfrousihzadeh MA, Jaffray F, Reiszadeh MR, Ansari N. The therapeutic effect of combined cryotherapy, paramomycin, and intralesional meglumine antimoniate in treating lupoid leishmaniasis and chronic leishmaniasis. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:989–991. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2006.02748.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ardehali S, Sodeiphy M, Haghighi P, Rezai H, Vollum D. Studies on chronic (lupoid) leishmaniasis. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1980;74:439–445. doi: 10.1080/00034983.1980.11687365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bridenstine JB, Dolezal JF. Standarizating chemical peel solusion formulations to avoid mishaps. Great fluctuation in actual concentrations of trichloroacetic acid. J Dermatol surg Oncol. 1994;20:813–816. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.1994.tb03710.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Herrmann A, Wohlrab J, Sudeck H, Burchard GD, Marsch WC. Chronic lupoid leishmaniasis: a rare differential diagnosis in Germany for erythematous infiltrative facial plaques. Hautarzt. 2007;58:256–260. doi: 10.1007/s00105-006-1129-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Richard B, Odom WD, Berger TG. Parasitic infections, stings, and bites. In: Odom RB, James WD, Berger TG, editors. Andrew's Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 9th ed. Philadelphia, USA: W. B. Saunders Co; 2000. p. 528. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Babajev KB, Babajev OG, Korepanov VI. Treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis using a carbon dioxide laser. Bull WHO. 1991;69:103–106. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Azadeh B, Samad A, Ardehali S. Histological spectrum of cutaneous leishmaniasis due to Leishmania tropica. Trans Roy Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1985;79:631–636. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(85)90174-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Momeni AZ, Aminjavaheri M. Treatment of recurrent cutaneous leishmaniasis. Int J Dermatol. 1995;34:129–133. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1995.tb03598.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ganor S. The treatment of leishmaniasis recidivans with local injections of amphotericin B. Dermatol Int. 1967;6:141–143. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1967.tb05251.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Butler PG. Levamisole and immune response phenomena in cutaneous leishmaniasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1982;6:1070–1077. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(82)70092-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dogra J, Lal BB, Misra SN. Dapsone in the treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis. Int J Dermatol. 1986;25:398–400. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1986.tb03435.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bassiouny A. Cryosurgery in cutaneous leishmaniasis. Br J Dermatol. 1983;109:617–619. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1983.tb07689.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nilforoushzadeh MA, Jaffary F, Reiszadeh MR. Comparative effect of topical trichloroacetic acid and intralesional meglumine antimonate in the treatment of acute cutaneous leishmaniosis. Int J Pharmacol. 2006;2:633–636. [Google Scholar]