Abstract

Systemic hormones are key regulators of postnatal mammary gland development and play an important role in the etiology and treatment of breast cancer. Mammary ductal morphogenesis is controlled by circulating hormones, and these same hormones are also critical mediators of mammary stem cell fate decisions. Recent studies have helped further our understanding of the origin, specification, and fate of mammary stem cells during postnatal development. Here we review recent studies on the involvement of hormone receptors and several transcription factors in mammary stem/progenitor cell differentiation and lineage commitment.

BREAST CANCER is a genetically and clinically heterogeneous disease that may result from the malignant transformation of mammary stem and/or progenitor cells (1). Most of the recent success leading to a decrease in breast cancer mortality is thought to be the result of targeted therapy of hormone-dependent, estrogen receptor (ER)α-positive breast cancers (2,3), which account for the majority of breast cancers. In ERα-negative breast cancers and those that are resistant to targeted therapy, prognosis declines and patient survival is dramatically decreased. Therefore, it will be crucial to identify the cell of origin in different breast cancer subtypes and to understand the influence of hormonal stimulation on these cells to devise new treatments for all breast cancers.

Mammary gland development is a tightly coordinated series of events that is driven by both systemic hormones and local growth factors (reviewed in Refs. 4 and 5). At each stage of development, the epithelial and stromal compartments respond to different signals that control a balance between proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis. For example, numerous studies primarily using mouse models have revealed that estrogen is a critical requirement for ductal elongation during puberty, whereas progesterone and prolactin signaling are crucial during pregnancy and lactation (reviewed in Refs. 6 and 7). Likewise, different signals are required for the specification and cell fate determination of mammary stem and progenitor cells during lineage commitment throughout development. In addition to systemic hormones and local growth factors, an important role for cytokines in mammary cell fate and lineage determination has also been established and recently reviewed (8). In this review, we discuss recent studies in both human and mouse, focusing on the latter, that have helped define how systemic hormones/endocrine factors regulate stem cell fate and lineage commitment during mammary gland development. In addition, we review recent literature that has established a critical role for various transcription factors in epithelial cell lineage commitment during different stages of postnatal development.

Hormonal Cues during Ductal Morphogenesis

The adult virgin mammary gland is comprised of two major types of epithelium, luminal and basal, which together form a ductal network embedded within the stroma. The luminal cells line the ducts as a single layer of epithelia, and the basal component consists of myoepithelial cells that are in direct contact with the adjacent stroma. At the onset of puberty, circulating ovarian and pituitary hormones such as estrogens, progestins and GH, initiate and drive ductal morphogenesis.

Unlike embryogenesis, postnatal mammary gland development relies on proper spatial patterning of steroid hormone receptors. Approximately 25–30% of the ductal luminal cells are ERα/progesterone receptor (PR)-positive that exhibit a nonuniform pattern of expression. This nonuniform expression pattern is shared by the prolactin receptor (PrlR), and it has been suggested that ERα, PR and PrlR are colocalized to the same cells (9). Importantly, the proliferating cells in the mature gland are steroid receptor negative and are regulated by ER/PR-positive cells by a paracrine mechanism (10,11). Disruption of hormone receptor patterning results in the inability to respond properly to systemic hormones, leading to a block in lobuloalveolar development during pregnancy (12). It should be noted that luminal epithelial cells in the mature mammary gland exhibit two distinct morphologies (13): tall, columnar-like and round, cuboidal-like. The former are nonproliferating, steroid receptor-negative cells, whereas the latter either express ERα/PR or are proliferating. Although the functional significance of these luminal cell types remains unclear, it is evident that the precise patterning of steroid and prolactin receptors in the normal mammary gland is required to elicit the appropriate paracrine response to local growth factors.

Mouse Mammary Stem Cells and ER

The existence of adult mammary stem cells was established nearly 50 yr ago when DeOme et al. (14) observed that tissue fragments of epithelium isolated from several different regions of the mammary gland were able to reconstitute the entire mammary ductal tree upon transplantation. Later, serial transplantation experiments by Charles Daniel and colleagues (15) demonstrated that stem cells exist throughout the life span of the mouse. Further studies by Smith and Medina (16) suggested that mammary stem cells were present in all portions of the ductal mammary tree at all developmental stages. However, in both mouse and human, studies have been hindered by the inability to identify definitive and exclusive stem/progenitor cell markers.

Despite these obstacles, considerable progress has recently been made in the field of mammary gland stem cell biology. In 2006, two complementary studies demonstrated that a single cell from either the CD24+ (heat-stable antigen)/CD29hi (β1-integrin) (17) or CD24+/CD49fhi (α6-integrin) (18) epithelial population isolated from an adult virgin mouse could generate a functional mammary gland when transplanted into the cleared fat pad of recipient mice. Further analysis of the CD24+CD29hi cells revealed that this was a basal population of cells that was ERα-negative (19). Limiting dilution transplantation experiments by Smalley and co-workers (20) illustrated that CD24lo ERα-negative basal cells displayed the highest stem cell activity (as defined by mammary repopulating units), whereas ERα-positive luminal cells exhibited very little stem cell activity.

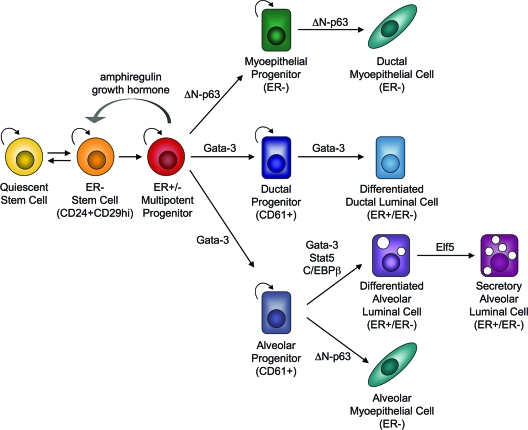

Conversely, Booth and Smith (21) suggested that long-lived, slow-dividing, label-retaining ERα-positive cells comprise a stem/progenitor cell population that can directly respond to hormones. The relationship of these cells characterized in situ to the CD24lo cells identified by fluorescence-activated cell sorting remains to be established. Using an elegant genetic chimeric approach, Brisken and co-workers (22) transplanted cells derived from ERα knockout mice to demonstrate that estrogen facilitates epithelial proliferation and morphogenesis by a paracrine mechanism. The results of their study suggested that nonproliferating ERα-positive cells are required to stimulate the proliferation of neighboring stem/progenitor cells during ductal outgrowth. These results raise an important question: how then can a single ERα-negative stem cell give rise to a fully functional mammary gland upon transplantation? Wicha and colleagues (23) hypothesized that ERα-negative stem cells can give rise to undifferentiated steroid receptor-positive cells, which subsequently proliferate in response to estrogen and secrete paracrine factors that regulate adjacent ERα-negative cells. Likewise, we proposed that a basal ERα-negative stem cell may divide asymmetrically once to give rise to a luminal ERα-positive progenitor cell (24). This undifferentiated cell would then secrete paracrine factors in response to estrogen stimulation to feedback on ERα-negative stem cells and induce their proliferation. Additionally, these same paracrine factors may induce the proliferation and/or differentiation of adjacent ERα-negative and ERα-positive progenitor cells (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Regulation of mammary stem cells by hormones, growth factors, and transcription factors during lineage commitment. ER-negative stem cells undergo asymmetric division to give rise to undifferentiated, ER-positive progenitor cells, which in response to estrogens, secrete paracrine factors that regulate ER-negative stem cells. These multipotent progenitor cells may also differentiate into basal-restricted (green) or luminal-restricted progenitors (dark blue), and alveolar-restricted lineages (gray) (36,37). As a result of estrogen stimulation during ductal morphogenesis, Gata-3 may specify luminal cell fate, whereas ΔN-p63 is important for basal cell lineages. During pregnancy, prolactin-mediated Gata-3 may contribute to alveolar cell development, and Elf5 establishes the secretory alveolar lineage.

Lineage Commitment during Puberty and Pregnancy

These and other studies provide evidence for a hierarchical model in which all types of epithelial cells in the mammary gland, including ductal luminal, alveolar luminal, and myoepithelial originate from a common multipotent stem cell. Although several such models have been proposed, the precise genetic mechanisms that regulate stem/progenitor differentiation and lineage commitment during mammary gland development remain ill defined. A series of recent publications, however, have helped elucidate a critical role for several different transcription factors in mammary lineage specification.

The Gata family of zinc-finger transcription factors plays fundamental roles in cell fate determination in multiple systems, including kidney, skin, nervous system, and the immune system. The Werb (25) and Visvader (26) laboratories have recently demonstrated that Gata-3 is essential for mammary gland development. Conditional deletion of Gata-3 using mouse mammary tumor virus-Cre resulted in the failure of terminal end bud formation and consequently, a significant reduction in ductal outgrowth. Notably, this phenotype is reminiscent of that observed in ERα-null mammary glands, and ERα expression was reduced in the Gata-3 null glands. Gata-3 was shown to bind directly to the promoter of the forkhead transcription factor FOXA1, which has been suggested to be essential for estrogen signaling in the mammary gland and required for binding of ERα to chromatin (27). Using breast cancer cell lines, Myles Brown and colleagues (28) demonstrated that Gata-3 is required for estrogen-mediated cell growth. Furthermore, ERα was shown to directly stimulate Gata-3 transcription, suggesting a positive cross-regulatory feedback loop between these two factors. Whether this feedback loop exists in the normal mammary gland remains to be established. Collectively, these studies indicate that Gata-3 is part of a unique transcriptional feedback network that may control important cell fate decisions in response to estrogen during ductal morphogenesis.

In addition to regulating ductal branching and elongation, Gata-3 plays a key role in mammary luminal cell differentiation. Gata-3 expression is profoundly decreased in PrlR and PR knockout mice, which also display failed alveolar development and lactogenesis (29,30). Several conditional deletion strategies have been employed to ablate Gata-3 at different stages of pregnancy. Acute loss of Gata-3 by a doxycycline-inducible whey acidic protein (WAP)-rtTA-Cre line led to the expansion of undifferentiated luminal cells (25). Similarly, WAP-Cre driven Gata-3 deficiency resulted in a block in alveolar differentiation and failed lactogenesis (26). Fluorescence-activated cell sorting analysis of a luminal progenitor population (CD29loCD24+CD61+) in Gata-3-null glands revealed that the proportion of CD61+ (β3-integrin) cells was significantly increased in the absence of Gata-3. Retroviral reintroduction of Gata-3 into this unique stem cell-enriched population promoted maturation along the alveolar luminal lineage, because β-casein and WAP transcripts were induced even in the absence of lactogenic hormones (26). Collectively, these data indicate that loss of Gata-3 blocks luminal progenitor cell differentiation and that Gata-3 promotes the differentiation of lineage-restricted progenitor cells.

Impaired alveolar differentiation is a phenotype shared by several other knockout models, including Stat5, Id2, CCAAT/enhancer binding protein β, and Elf5. Elf5 is an Ets transcription factor and member of the PrlR signaling pathway that was recently shown to play a key role in alveolar cell fate specification (31). Like Gata-3, Elf5 levels are drastically reduced in PrlR-null mammary glands, suggesting that it is an important mediator of alveolar differentiation (32). Elf5-deficient mice are embryonic lethal due to placentation defects, but Elf5 heterozygotes display defective lobuloalveolar development and reduced milk secretion during pregnancy. Harris et al. (33) demonstrated that retroviral re-expression of Elf5 in PrlR-null mammary epithelial cells (MECs) followed by transplantation rescued alveolar morphogenesis, compensating for the loss of PrlR signaling. Ormandy and colleagues (31) demonstrated that forced overexpression of Elf5 using a doxycyclin-inducible model resulted in disrupted ductal morphogenesis and precocious alveolar differentiation and milk secretion in virgin mice. Analysis of luminal progenitor cells (CD29loCD24+CD61+) in transplanted glands revealed that there was a significant accumulation of this population in Elf5-null MECs during pregnancy compared with wild type, a result that was shared by midpregnant Elf+/− mice. The authors concluded that Elf5 deficiency causes a block in CD29loCD24+CD61+ luminal cell differentiation, and that Elf5 specifies secretory alveolar cell fate from this progenitor cell population. Although Gata-3 and Elf5-null mammary glands display similar phenotypes, Gata-3 appears to regulate luminal cell specification, whereas Elf5 is required to establish the secretory alveolar lineage during pregnancy. Whether Gata-3 and Elf5 cooperate in luminal progenitor cells to regulate alveolar differentiation remains to be determined.

Steroid Hormones in Human Mammary Stem Cells

Although the molecular mechanisms of hormonal regulation of mouse mammary stem/progenitor cells are just beginning to be unraveled, the interactions between endocrine factors and human stem cells remain largely unexplored. While numerous putative stem and progenitor cell markers have been proposed, the effects of estrogen on these populations, for example, have yet to be determined. Dontu and colleagues (1) recently reported that increased aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH)-1 activity is associated with increased stem cell properties in human MECs (HMECs). Limiting dilution transplantation into humanized cleared fat pads of NOD/SCID (nonobese diabetic/severe combined immunodeficient) mice showed that only ALDEFLUOR-positive HMECs, indicative of high ALDH1 activity, could generate ductal outgrowth. Likewise, ALDEFLUOR-positive breast cancer cells were enriched in tumor-initiating ability when xenografted at limiting dilution. Finally, ALDH1 activity was associated with poor clinical outcome when a panel of 577 breast cancers was examined. In summary, these data demonstrate that in both normal and cancer human mammary epithelial cells, ALDH1 activity marks a population that displays increased stem cell activity (1).

What then is the relationship between ERα and ALDH1 activity in human mammary stem cells? In a recent study by Wicha and colleagues (34), the breast cancer susceptibility gene BRCA1, which has well-established roles in DNA repair and chromosome stability, was shown to be a mediator of mammary cell fate specification. Deletion of BRCA1 in primary HMECs resulted in the expansion of stem cell populations defined by ALDH1 activity. Additionally, ERα-positive cells were decreased in BRCA1-null HMECs in vitro, and transplantation of these cells produced outgrowths that uniformly expressed ALDH1 but lacked ERα expression. These results suggest that BRCA1 plays a role in the differentiation of ALDH1-positive/ER-negative stem/progenitor cells into ER-positive luminal epithelial cells. Wicha and colleagues (34) proposed that loss of BRCA1 causes impaired luminal epithelial cell differentiation and results in an accumulation of ALDH1-positive/ER-negative stem cells. These studies suggest that loss of BRCA1 function may cause a block in epithelial cell differentiation and the expansion of undifferentiated, ER-negative stem cells.

Conclusions

Although considerable progress has been made in the characterization of mammary stem cells, the molecular and genetic mechanisms that regulate their self-renewal, maintenance, differentiation and survival remain poorly understood. Here we summarized various reports that suggest that endocrine factors and steroid hormones have significant roles in cell fate specification, although elucidation of these mechanisms has only just begun. In response to hormonal stimulation during different stages of development, luminal progenitor cells may commit to either a ductal or alveolar fate. A model for a hierarchy of stem/progenitor cell differentiation and lineage commitment is presented in Fig. 1.

Estrogen signaling is fundamental to normal mammary gland development and plays a central role in promoting the proliferation of neoplastic breast epithelium. ERα is one of the most important prognostic factors of breast cancer and its expression can dictate clinical outcome. However, the precise role(s) of ERα in normal and cancer stem cells remains controversial. Several important questions remain unanswered: In the mouse, how can a single ER-negative stem cell give rise to a functional mammary gland when ductal outgrowth and epithelial cell proliferation require ERα? Is there a population of quiescent mammary stem cells and what is the local microenvironment or “niche” for these cells? Recent studies have suggested that the ΔN-p63 isoform may be involved in commitment of the basal mammary epithelial cell lineage (35), but the mechanisms that regulate the expression of this isoform remain to be established. What are the local factors that regulate basal and luminal epithelial cell commitment and are these regulated by systemic hormones? Answering these questions will be essential to devising new therapeutic strategies that target tumor-initiating cells in both hormone-responsive and hormone-negative breast cancers.

Footnotes

Studies in our laboratory are supported by National Institutes of Health Grant CA030195-22 (to J.M.R.), and Heather LaMarca is the recipient of an American Cancer Society Tricam Industries Postdoctoral Breast Cancer Fellowship (PF-06-252-01-MGO).

First Published Online June 12, 2008

Abbreviations: ALDH, Aldehyde dehydrogenase; ER, estrogen receptor; HMECs, human MECs; MECs, mammary epithelial cells; PR, progesterone receptor; PrlR, prolactin receptor; WAP, whey acidic protein.

References

- Ginestier C, Hur MH, Charafe-Jauffret E, Monville F, Dutcher J, Brown M, Jacquemier J, Viens P, Kleer CG, Liu S, Schott A, Hayes D, Birnbaum D, Wicha MS, Dontu G 2007 ALDH1 is a marker of normal and malignant human mammary stem cells and a predictor of poor clinical outcome. Cell Stem Cell 1:555–567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2005 Effects of chemotherapy and hormonal therapy for early breast cancer on recurrence and 15-year survival: an overview of the randomised trials. Lancet 365:1687–1717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peto R, Boreham J, Clarke M, Davies C, Beral V 2000 UK and USA breast cancer deaths down 25% in year 2000 at ages 20–69 years. Lancet 355:1822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hennighausen L, Robinson GW 2001 Signaling pathways in mammary gland development. Dev Cell 1:467–475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oakes SR, Hilton HN, Ormandy CJ 2006 The alveolar switch: coordinating the proliferative cues and cell fate decisions that drive the formation of lobuloalveoli from ductal epithelium. Breast Cancer Res 8:207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brisken C 2002 Hormonal control of alveolar development and its implications for breast carcinogenesis. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia 7:39–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sternlicht MD, Kouros-Mehr H, Lu P, Werb Z 2006 Hormonal and local control of mammary branching morphogenesis. Differentiation 74:365–381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson CJ, Khaled WT 2008 Mammary development in the embryo and adult: a journey of morphogenesis and commitment. Development 135:995–1003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hovey RC, Trott JF, Ginsburg E, Goldhar A, Sasaki MM, Fountain SJ, Sundararajan K, Vonderhaar BK 2001 Transcriptional and spatiotemporal regulation of prolactin receptor mRNA and cooperativity with progesterone receptor function during ductal branch growth in the mammary gland. Dev Dyn 222:192–205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke RB, Howell A, Potten CS, Anderson E 1997 Dissociation between steroid receptor expression and cell proliferation in the human breast. Cancer Res 57:4987–4991 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seagroves TN, Lydon JP, Hovey RC, Vonderhaar BK, Rosen JM 2000 C/EBPβ (CCAAT/enhancer binding protein) controls cell fate determination during mammary gland development. Mol Endocrinol 14:359–368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimm SL, Seagroves TN, Kabotyanski EB, Hovey RC, Vonderhaar BK, Lydon JP, Miyoshi K, Hennighausen L, Ormandy CJ, Lee AV, Stull MA, Wood TL, Rosen JM 2002 Disruption of steroid and prolactin receptor patterning in the mammary gland correlates with a block in lobuloalveolar development. Mol Endocrinol 16:2675–2691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ismail PM, Li J, DeMayo FJ, O'Malley BW, Lydon JP 2002 A novel LacZ reporter mouse reveals complex regulation of the progesterone receptor promoter during mammary gland development. Mol Endocrinol 16:2475–2489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeOme KB, Faulkin Jr LJ, Bern HA, Blair PB 1959 Development of mammary tumors from hyperplastic alveolar nodules transplanted into gland-free mammary fat pads of female C3H mice. Cancer Res 19:515–520 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young LJ, Medina D, DeOme KB, Daniel CW 1971 The influence of host and tissue age on life span and growth rate of serially transplanted mouse mammary gland. Exp Gerontol 6:49–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith GH, Medina D 1988 A morphologically distinct candidate for an epithelial stem cell in mouse mammary gland. J Cell Sci 90(Pt 1):173–183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shackleton M, Vaillant F, Simpson KJ, Stingl J, Smyth GK, Asselin-Labat ML, Wu L, Lindeman GJ, Visvader JE 2006 Generation of a functional mammary gland from a single stem cell. Nature 439:84–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stingl J, Eirew P, Ricketson I, Shackleton M, Vaillant F, Choi D, Li HI, Eaves CJ 2006 Purification and unique properties of mammary epithelial stem cells. Nature 439:993–997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asselin-Labat ML, Shackleton M, Stingl J, Vaillant F, Forrest NC, Eaves CJ, Visvader JE, Lindeman GJ 2006 Steroid hormone receptor status of mouse mammary stem cells. J Natl Cancer Inst 98:1011–1014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sleeman KE, Kendrick H, Robertson D, Isacke CM, Ashworth A, Smalley MJ 2007 Dissociation of estrogen receptor expression and in vivo stem cell activity in the mammary gland. J Cell Biol 176:19–26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booth BW, Smith GH 2006 Estrogen receptor-α and progesterone receptor are expressed in label-retaining mammary epithelial cells that divide asymmetrically and retain their template DNA strands. Breast Cancer Res 8:R49 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallepell S, Krust A, Chambon P, Brisken C 2006 Paracrine signaling through the epithelial estrogen receptor α is required for proliferation and morphogenesis in the mammary gland. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103:2196–2201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dontu G, El-Ashry D, Wicha MS 2004 Breast cancer, stem/progenitor cells and the estrogen receptor. Trends Endocrinol Metab 15:193–197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaMarca HL, Rosen JM 2007 Estrogen regulation of mammary gland development and breast cancer: amphiregulin takes center stage. Breast Cancer Res 9:304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kouros-Mehr H, Slorach EM, Sternlicht MD, Werb Z 2006 GATA-3 maintains the differentiation of the luminal cell fate in the mammary gland. Cell 127:1041–1055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asselin-Labat ML, Sutherland KD, Barker H, Thomas R, Shackleton M, Forrest NC, Hartley L, Robb L, Grosveld FG, van der Wees J, Lindeman GJ, Visvader JE 2007 Gata-3 is an essential regulator of mammary-gland morphogenesis and luminal-cell differentiation. Nat Cell Biol 9:201–209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll JS, Liu XS, Brodsky AS, Li W, Meyer CA, Szary AJ, Eeckhoute J, Shao W, Hestermann EV, Geistlinger TR, Fox EA, Silver PA, Brown M 2005 Chromosome-wide mapping of estrogen receptor binding reveals long-range regulation requiring the forkhead protein FoxA1. Cell 122:33–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eeckhoute J, Keeton EK, Lupien M, Krum SA, Carroll JS, Brown M 2007 Positive cross-regulatory loop ties GATA-3 to estrogen receptor α expression in breast cancer. Cancer Res 67:6477–6483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ormandy CJ, Camus A, Barra J, Damotte D, Lucas B, Buteau H, Edery M, Brousse N, Babinet C, Binart N, Kelly PA 1997 Null mutation of the prolactin receptor gene produces multiple reproductive defects in the mouse. Genes Dev 11:167–178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ormandy CJ, Naylor M, Harris J, Robertson F, Horseman ND, Lindeman GJ, Visvader J, Kelly PA 2003 Investigation of the transcriptional changes underlying functional defects in the mammary glands of prolactin receptor knockout mice. Recent Prog Horm Res 58:297–323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oakes SR, Naylor MJ, Asselin-Labat ML, Blazek KD, Gardiner-Garden M, Hilton HN, Kazlauskas M, Pritchard MA, Chodosh LA, Pfeffer PL, Lindeman GJ, Visvader JE, Ormandy CJ 2008 The Ets transcription factor Elf5 specifies mammary alveolar cell fate. Genes Dev 22:581–586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J, Chehab R, Tkalcevic J, Naylor MJ, Harris J, Wilson TJ, Tsao S, Tellis I, Zavarsek S, Xu D, Lapinskas EJ, Visvader J, Lindeman GJ, Thomas R, Ormandy CJ, Hertzog PJ, Kola I, Pritchard MA 2005 Elf5 is essential for early embryogenesis and mammary gland development during pregnancy and lactation. EMBO J 24:635–644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris J, Stanford PM, Sutherland K, Oakes SR, Naylor MJ, Robertson FG, Blazek KD, Kazlauskas M, Hilton HN, Wittlin S, Alexander WS, Lindeman GJ, Visvader JE, Ormandy CJ 2006 Socs2 and elf5 mediate prolactin-induced mammary gland development. Mol Endocrinol 20:1177–1187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S, Ginestier C, Charafe-Jauffret E, Foco H, Kleer CG, Merajver SD, Dontu G, Wicha MS 2008 BRCA1 regulates human mammary stem/progenitor cell fate. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105:1680–1685 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li N, Singh S, Cherukuri P, Li H, Yuan Z, Ellisen LW, Wang B, Robbins D, Direnzo J 2008 Reciprocal intraepithelial interactions between TP63 and hedgehog signaling regulate quiescence and activation of progenitor elaboration by mammary stem cells. Stem Cells 26:1253–1264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booth BW, Boulanger CA, Smith GH 2007 Alveolar progenitor cells develop in mouse mammary glands independent of pregnancy and lactation. J Cell Physiol 212:729–736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner KU, Boulanger CA, Henry MD, Sgagias M, Hennighausen L, Smith GH 2002 An adjunct mammary epithelial cell population in parous females: its role in functional adaptation and tissue renewal. Development 129: 1377–1386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]