Abstract

Excitation–contraction (E–C) coupling is the mechanism that connects the electrical excitation with cardiomyocyte contraction. Embryonic cardiomyocytes are not only capable of generating action potential (AP)-induced Ca2+ signals and contractions (E–C coupling), but they also can induce spontaneous pacemaking activity. The spontaneous activity originates from spontaneous Ca2+ releases from the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR), which trigger APs via the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger (NCX). In the AP-driven mode, an external stimulus triggers an AP and activates voltage-activated Ca2+ intrusion to the cell. These complex and unique features of the embryonic cardiomyocyte pacemaking and E–C coupling have never been assessed with mathematical modeling. Here, we suggest a novel mathematical model explaining how both of these mechanisms can coexist in the same embryonic cardiomyocytes. In addition to experimentally characterized ion currents, the model includes novel heterogeneous cytosolic Ca2+ dynamics and oscillatory SR Ca2+ handling. The model reproduces faithfully the experimentally observed fundamental features of both E–C coupling and pacemaking. We further validate our model by simulating the effect of genetic modifications on the hyperpolarization-activated current, NCX, and the SR Ca2+ buffer protein calreticulin. In these simulations, the model produces a similar functional alteration to that observed previously in the genetically engineered mice, and thus provides mechanistic explanations for the cardiac phenotypes of these animals. In general, this study presents the first model explaining the underlying cellular mechanism for the origin and the regulation of the heartbeat in early embryonic cardiomyocytes.

INTRODUCTION

In this issue (see p. 397), we presented experimental characterization and central functional components of the excitation–contraction (E–C) coupling and pacemaking of embryonic (E9-E11) mouse ventricular cardiomyocytes (Rapila et al., 2008). According to the experiments, these cells are capable of maintaining their activity alone by producing spontaneous cytosolic calcium oscillations upon repetitive calcium releases from the SR as suggested earlier (Sasse et al., 2007). The same cells are also capable of producing action potential (AP)-induced calcium influx and subsequent CICR from the SR upon electrical stimulation. In the developing heart, the APs triggered could conduct from cell to cell, thereby synchronizing the electrical activity and contraction of adjacent cells. In addition to this, we identified the mechanisms behind the spontaneous activity of the SR release. We showed that these calcium oscillations require functional ryanodine receptors (RyRs), inositol-3-phosphate receptors (IP3Rs), and SR Ca2+ ATPase (SERCA) (Rapila et al., 2008). Further, we showed that the frequency of the spontaneous oscillations depends on the calcium leak through the IP3Rs, which provides a mechanism for the regulation of the heart rate of the embryonic heart. Collectively, the detailed experimental characterization of the individual features of E–C coupling and pacemaking in E9-E11 myocytes introduces a view of a rather complicated array of cellular functions. Therefore, to further analyze how these different mechanisms operate in parallel, we built a mathematical model into which we incorporated the experimentally characterized components of calcium signaling and excitability of these cells. Mathematical modeling has been widely used as a tool in explaining and studying E–C coupling in adult cardiomyocytes (Luo and Rudy, 1994; Dokos et al., 1996; Jafri et al., 1998; Pandit et al., 2001; Bondarenko et al., 2004). However, based on our results, the differences between embryonic and adult cardiomyocytes are so dramatic that novel approaches are required to model the embryonic cardiomyocyte E–C coupling and pacemaking. In embryonic cardiomyocytes, the cytosolic Ca2+ signals are more heterogeneous than in adult cardiomyocytes (Rapila et al., 2008). Therefore, instead of the common pool approach used in the adult myocyte models (Luo and Rudy, 1994; Dokos et al., 1996; Jafri et al., 1998; Pandit et al., 2001; Bondarenko et al., 2004), a more detailed description of the cytosolic Ca2+ dynamics was required. In addition, the SRs in adult models (Luo and Rudy, 1994; Dokos et al., 1996; Jafri et al., 1998; Pandit et al., 2001; Bondarenko et al., 2004) produce only calcium-triggered, nonspontaneous Ca2+ releases. Spontaneous SR and ER Ca2+ oscillations, such as those triggering the activity of the embryonic cardiomyocytes, have been described and modeled in a variety of other cell types (Deyoung and Keizer, 1992; Keizer and Levine, 1996; Sneyd et al., 2003), but not in cardiomyocytes. Therefore, to model the E9-E11 cardiomyocyte E–C coupling and pacemaking, this type of SR dynamics had to be introduced to the model.

Here, we present a model of E–C coupling and pacemaking in E9-E11 mouse ventricular cardiomyocytes with the novel features described above. For developing the model, we also characterized the major ion currents in the sarcolemmal (SL) membrane of E9-E11 cardiomyocytes. The model is constructed based on this electrophysiological data and data from our accompanying paper (Rapila et al., 2008). We use the model to study if the identified SL ion currents and the SR components (IP3R, RyR, and SERCA) are sufficient to explain the function of E9-E11 cardiomyocytes. With the model we show the following: (1) IP3R, RyR, and SERCA, with obligatory roles for all, can produce spontaneous cytosolic Ca2+ oscillations at the rate of ∼0.2–1.1 Hz; and (2) the identified SL ion currents together compose an excitable membrane that (a) produces APs when cytosolic Ca2+ oscillates spontaneously, (b) produces APs and CICRs when exposed to external electrical excitation, and (c) is quiescent without either of these stimuli. We further simulate the model with modified hyperpolarization-activated current (If), Na+/Ca2+ exchanger (NCX), and SR Ca2+ buffer calreticulin amounts and show that our simulations are in line with previous experimental studies with corresponding transgenic animals (Mesaeli et al., 1999; Wakimoto et al., 2000; Nakamura et al., 2001; Stieber et al., 2003). These simulations validate our model further and also provide the underlying mechanism for the observed E–C coupling and pacemaking alterations in these transgenic animals.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Electrophysiological Recordings

The cell isolation and culturing and the electrophysiological recordings were performed as described in this issue in Rapila et al. (2008). The used solutions and recording methods are summarized in Table S1, which is available at http://www.jgp.org/cgi/content/full/jgp.200809961/DC1. Ion currents were measured at +25°C. The membrane currents were scaled by dividing them with the measured cell membrane capacitance.

Mathematical Model of the Embryonic Ventricular Myocyte

A mathematical model of the E9-E11 embryonic mouse ventricular myocyte was developed and simulated. The model describes the function of SR and SL ion channels, membrane voltage dynamics, and cytosolic Ca2+, Na+ and K+, and SR Ca2+ concentration dynamics. A fundamental feature of the model is that in addition to a time coordinate, the cytosolic Ca2+ concentration is also modeled as a function of a spatial coordinate. All parameters of the components and the environmental parameters of the model were fitted to our own experimental data and experimental conditions (in this and in Rapila et al. [2008]) whenever possible and necessary. Complete model equations are shown in the Supplemental text, which is available at http://www.jgp.org/cgi/content/full/jgp.200809961/DC1.

Structure of the Model.

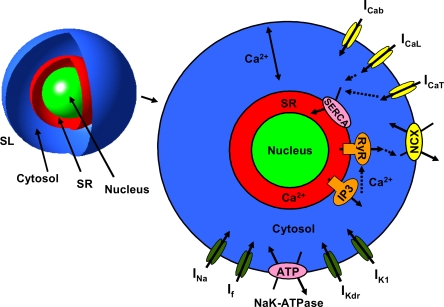

As shown in Fig. 1, the cell and the intracellular structures were assumed to have spherical shapes. The nucleus is located in the center of the cell and the SR on the surface of the nucleus, and the cytosol is the space between the SL and SR. The dimensions of the structure were estimated from our confocal and light microscope images and from patch-clamp data by calculating the membrane area and rcell from the membrane capacitance (Table S2, available at http://www.jgp.org/cgi/content/full/jgp.200809961/DC1).

Figure 1.

A schematic diagram of the mathematical model of the mouse early embryonic (E9-E11) cardiomyocyte. The SL components are background Ca2+ current (ICab), ICaL, ICaT, NCX, IK1, IKDR, NaK-ATPase, If, and INa. The SR components are Ca2+ pump (SERCA), RyR, and IP3R. Ca2+ diffuses radially in the cytosol and is buffered to troponin and calmodulin in cytosol and to calreticulin in the SR. The model also includes dynamic cytosol Na+ and K+ concentrations. The compartments are not in scale.

Ca2+ Diffusion and Buffering in Cytosol.

The spatial differences of the Ca2+ concentration within the cytosol were modeled using Fick's law of diffusion. For the calcium diffusion coefficient DCa of the model, we used the value previously reported for calcium in water, 0.79 μm2/ms (Cussler, 1997) (Table S5, available at http://www.jgp.org/cgi/content/full/jgp.200809961/DC1). With this DCa value, the model reproduced well the delay in Ca2+ signal between cytosol areas below the SR and SL, which was experimentally defined by Rapila et al. (2008) (28.5 ± 4.9 ms; n = 12). Due to the shape of the model cell, the diffusion is modeled using spherical coordinates and by assuming radial symmetry. The cytosolic Ca2+ buffering of troponin C and calmodulin is modeled as described previously (Luo and Rudy, 1994). The free and buffered Ca2+ concentrations are calculated for all radii values between boundaries. Embryonic myocytes have a lower Ca2+ binding capacity than adult myocytes, which is mostly caused by a lower troponin C concentration (Creazzo et al., 2004). Based on this, we reduced the amount of troponin C to 30% and calmodulin to 75% of the original values.

SL Ion Channels.

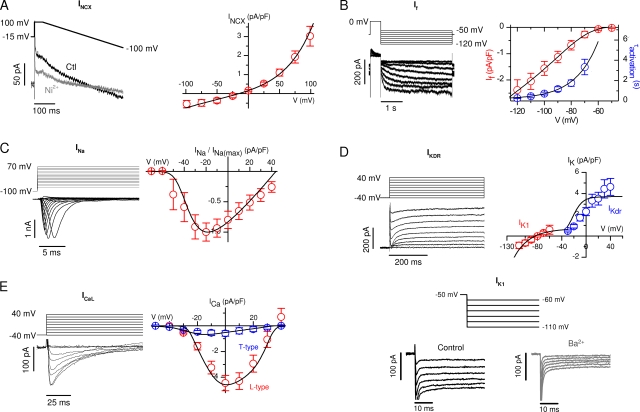

The models of the NCX (Luo and Rudy, 1994), If (Pandit et al., 2001), fast Na+ current (INa) (Bondarenko et al., 2004), slowly activated delayed rectifier K+ current (IKDR) (Dokos et al., 1996), time-independent background K+ current (IK1) (Dokos et al., 1996), L-type Ca2+ current (ICaL) (Bondarenko et al., 2004), and T-type Ca2+ current (ICaT) (Dokos et al., 1996) were fitted to our whole cell voltage-clamp data (Fig. 2). The fitted conductances were scaled from T = 25°C (in Fig. 2) to T = 34°C with Q10 = 1.35 (Hart, 1983; Hille, 2001), except Q10-NCX = 1.6 (Debetto et al., 1990; Puglisi et al., 1996; Shannon et al., 2004) and Q10-ICaL = 1.8 (Puglisi et al., 1999; Shannon et al., 2004). The If time constant was scaled with Q10 = 3 (Hart, 1983; Hille, 2001). As described previously, the fitting of the INa was based partly on the AP upstroke properties (Bondarenko et al., 2004). The background Ca2+ current is modeled as a linear ohmic current and fitted to obtain a physiologically correct diastolic [Ca2+] (∼0.1–0.2 μM). The model of the NaK-ATPase (Luo and Rudy, 1994) was fitted to maintain physiologically correct intracellular Na+ and K+ concentrations (∼14 and ∼140 mM, respectively). The ion currents change the cytosolic [Ca2+] below the SL and the cytosolic common pool [Na+] and [K+].

Figure 2.

The current–voltage relations of the ion currents in the E9-E11 mouse cardiomyocytes and in the mathematical model. (A) INCX, (B) If (the activation time constant is also shown), (C) INa, (D) IK1 and IKDR, and (E) T- and L-type calcium channels (top right panel). In each case, red or blue symbols denote the experimentally defined features of the ion currents that were adopted into the model (black solid lines). The representative recordings are shown in the left column of each panel.

SR.

SR is modeled as a common pool compartment for Ca2+ ions. In the SR the Ca2+ is buffered with calreticulin using a similar buffering model as in the cytosol. Ca2+ ions move from the SR to the cytosol via RyR and IP3R and from the cytosol to SR via SERCA. The models of these channels and the Ca2+ flux via these channels interact with the cytosolic [Ca2+] below the SR ([Ca2+]subSR). The function of RyR is modeled using a previously published model (Keizer and Levine, 1996). The function of IP3R is modeled using a model that takes the [IP3] as an input parameter and computes the IP3R Ca2+ flux based on the open (O) and active (A) states of the receptor (Sneyd and Dufour, 2002). The results presented here were simulated using [IP3] = 0.075 μM unless stated otherwise. The model of SERCA (Jafri et al., 1998) is used with half-maximal activation by [Ca2+]subSR set to 0.25 μM (Frank et al., 2000).

The values for calreticulin concentration, amounts of SR ion channels, and [IP3] were fitted to give a physiologically relevant [Ca2+] transient amplitude, a fractional release comparable to our measurements, and spontaneous Ca2+ oscillation frequencies that are comparable to the experimentally observed range of oscillation frequencies (0.1–1.3 Hz; Rapila et al. [2008]).

Simulation Methods.

The model consists of 31 ordinary differential equations combined with one partial differential equation. The model was simulated in the Matlab 6.5 (The Mathworks) environment using a self-written solver algorithm for combined partial and ordinary differential equation systems based on the forward Euler method (Korhonen and Tavi, 2008). We used a spatial step size of Δr = 0.1 μm and time step sizes of Δt = 1–0.00001 ms to obtain solutions with a relative error of <0.1% at each integration step. The simulations shown here were started from the steady-state initial conditions. The steady-state conditions were obtained by simulating the model until the intracellular ion concentrations were stable. The electrical stimulation of the model cell was simulated by applying a stimulus current of −80 pA/pF (−120 pA/pF in Fig. 5) for 0.5 ms. In some simulations, the models of individual ion channels were driven with a voltage-clamp protocol. The effect of caffeine was simulated by setting the diffusion rate of RyR Ca2+ flux to a large constant value (see Supplemental text). The SERCA Ca2+ flux was set to zero, as the Ca2+ is extruded almost completely with SL mechanisms when caffeine is applied to cardiomyocytes (Bers, 2001). The effect of IP3-AM seen in experiments was simulated by increasing the [IP3] slowly (10−3 μM/s) as the de-esterification of IP3-AM to IP3 in cytosol is not instant.

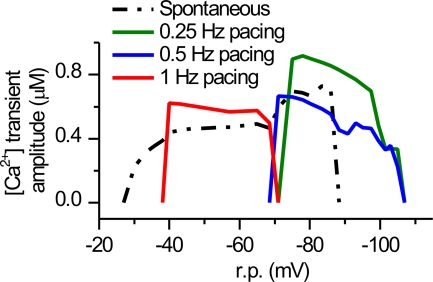

Figure 5.

The resting potential windows favoring spontaneous Ca2+ activity and Ca2+ activity generated by electrical pacing. A constant current from 4 to −2.5 pA/pF with 0.25 pA/pF intervals was applied to the model cell to adjust the r.p. of the model cell to values between −107 and −27 mV. At each r.p. value, the spontaneous and paced (0.25, 0.5, and 1 Hz) cytosolic Ca2+ activity was observed for 10 s after 40 s of stabilization of the model. The figure shows the average amplitudes spontaneously evoked and electrically stimulated cytosolic [Ca2+] transients at given frequency.

Data Analysis

Data analysis was made using the Clampfit 9.2 (MDS Analytical Technologies), Origin 7.5 (OriginLab Corporation), and Matlab 6.5 (The Mathworks) software. Clampfit's leak resistance subtraction and software filters were used when necessary.

Matlab's (The Mathworks) “nlinfit” function for nonlinear least-squares data fitting by the Gauss-Newton method was used to fit the model components to experimental data. Results are expressed as mean ± SEM.

Online Supplemental Material

The online supplemental material includes a table for the used solutions and recording methods in electrophysiological recordings (Table S1), the parameters of the model (Tables S2–S5), complete model equations (Supplemental text), a figure of the simulated effects of RyR, IP3R, and SERCA blocks (Fig. S1), and an animation of the simulated spontaneous activity (Video 1). The online supplemental material is available at http://www.jgp.org/cgi/content/full/jgp.200809961/DC1.

RESULTS

Electrophysiological Characterization of the Mouse E9-E11 Ventricular Myocytes

We identified seven major ion current types from E9-E11 mouse ventricular cardiomyocytes (Fig. 2). The INCX measured as the Ni2+-sensitive current had a density of −0.55 ± 0.19 pA/pF (n = 7) at −100 mV. The theoretical reversal potential for INCX in the recording solution (3ENa–2ECa = −15 mV) (Despa et al., 2003) agrees with the reversal potential in our experimental I-V relation for INCX (∼−12 mV, Fig. 2 A). As described previously (Yasui et al., 2001), we found an If current, which activates slowly (τ ∼0.3–3 s) upon hyperpolarization of the cell membrane. The threshold for the activation of If was ∼−70 mV (Fig. 2 B). The recorded INa current had a similar I-V relation shape, as described previously (Doevendans et al., 2000) (Fig. 2 C), and had a large peak current of −92.1 ± 13.8 pA/pF at −20 mV (n = 11). We identified two types of repolarizing K+ currents: an IKDR and an IK1 (Fig. 2 D). The IKDR is active at Vm above −30 mV, and it corresponds to the early repolarization of the AP. The IK1 operates at smaller Vm values and contributes to the late repolarization of the AP and to the resting potential (r.p.). Both L- and T-type voltage–activated Ca2+ channels are present in embryonic mouse cardiomyocytes (Seisenberger et al., 2000; Cribbs et al., 2001). We recorded the ICaL with a peak amplitude of −4.5 ± 0.6 pA/pF (n = 11) and ICaT with a peak amplitude of −0.59 ± 0.21 pA/pF (n = 5) (Fig. 2 E). We included all of these seven types of ion channels in the model with similar voltage-dependent behavior as recorded in our experiments (Fig. 2). In addition to these currents, the NaK-ATPase and background Ca2+ leak were included in the SL membrane (Fig. 1).

Simulation of the Pacemaking and E–C Coupling of an E9-E11 Cardiomyocyte

In Rapila et al. (2008) in this issue, we showed that the spontaneous Ca2+ signals in E9-E11 cardiomyocytes require both IP3R and RyR at the SR. We suggested that the Ca2+ leak via IP3R increases the cytosolic Ca2+ and triggers the Ca2+ release from RyR. In 48–72-h cultured early embryonic cardiomyocytes (Sasse et al., 2007) and in stem cell–derived differentiating cardiomyocytes (Mery et al., 2005), IP3Rs are able to produce [Ca2+]i oscillations alone. These kind of oscillations have been modeled before, and they require either biphasic (activation/inactivation) calcium-dependent modulation of IP3R (Atri et al., 1993) or oscillation of cytosolic [IP3] (Politi et al., 2006). Sensitivity to [IP3] is common to all IP3R isoforms (Ramos-Franco et al., 1998; Hagar and Ehrlich, 2000), whereas calcium-dependent inactivation is characteristic to IP3R–type 1 only (Hagar et al., 1998; Ramos-Franco et al., 1998). In our experiments (Rapila et al., 2008), IP3R activation alone did not produce spontaneous Ca2+ oscillations. Activation of IP3Rs produced only an [IP3]-dependent constant Ca2+ leak. Consequently, IP3Rs have no Ca2+-dependent inactivation with increasing [Ca2+]i. Because these calcium activation features are characteristic of the type 2 IP3R (Ramos-Franco et al., 1998), the predominant IP3R isoform in ventricular myocytes (Perez et al., 1997), we implemented a model of the type 2 IP3R (Sneyd and Dufour, 2002) to the SR of our mathematical model. Together with modeled RyRs (Keizer and Levine, 1996) and IP3Rs in the simulation of our model with no external stimulus, the model produces spontaneous activity that is initiated by a slowly increasing Ca2+ leak via IP3R from SR to cytosol (Fig. 3, A and B, and Video 1, which is available at http://www.jgp.org/cgi/content/full/jgp.200809961/DC1). When a certain threshold in cytosolic [Ca2+] near the SR is crossed, the RyRs are triggered and a large Ca2+ release occurs from the SR to the cytosol. Altogether, the simulated RyR and IP3R channels have quite different dynamic features; RyRs produce rapid transient openings, whereas the IP3R open probability changes slowly and remains almost constant in the time scale of the pacemaking cycle (Fig. 3 B and Video 1).

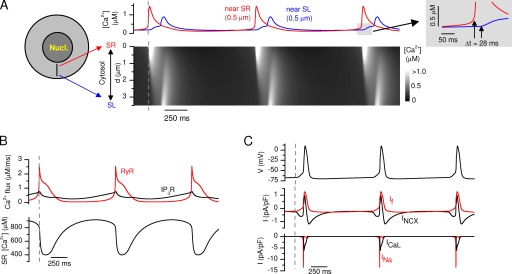

Figure 3.

Simulated cardiomyocyte spontaneous activity. (A) Near-SR and near-SL Ca2+ concentrations (top panel) from the simulated cytosolic calcium distribution (bottom panel). (B) The corresponding calcium fluxes through RyRs and IP3Rs and the SR Ca2+ concentration. (C) The corresponding APs accompanied by central ion currents: If with INCX and ICaL with INa.

The SR Ca2+ release and NCX have been shown to play a role in embryonic pacemaking (Sasse et al., 2007) and adult pacemaker cells (Bogdanov et al., 2001; Vinogradova et al., 2005). In our accompanying paper in this issue, we showed that the spontaneously released Ca2+ diffuses in the cytosol from SR to SL, where it triggers an AP (Rapila et al., 2008). The triggering of the AP was shown to depend on the INCX. E9-E11 cardiomyocytes have a relatively long diffusion distance from SR to SL, which is implemented into the model. Long distance results in a time delay between the near-SR and near-SL Ca2+ increment during simulated spontaneous SR Ca2+ release and cytosolic Ca2+ diffusion (Fig. 3 A and Video 1). The increment of the near-SL Ca2+ activates a depolarizing INCX current when NCX extrudes Ca2+ (Fig. 3 C and Video 1). The Vm depolarizes slowly until the threshold for INa activation is crossed and the AP is initiated. The activated INa causes rapid depolarization of the cell membrane and subsequently also activates the voltage-activated Ca2+ channels, ICaL and ICaT (Fig. 3 C and Video 1).

Even though the E9-E11 cardiomyocytes are capable of producing their cytosolic Ca2+ transients and subsequent APs spontaneously, the activity can also be synchronized with an external stimulus (Rapila et al., 2008). The cells can thus maintain their activity alone but also synchronize their activity with other cells to form coordinated contraction. In line with the experiments, the simulations showed that the pacemaking and E–C coupling mode can coexist in the same cell. We simulated the effect of an external electrical excitation during spontaneous activity of the model cell. The membrane voltage and intracellular Ca2+ oscillations were synchronized to the frequency of the stimulus, and the intracellular Ca2+ gradients were reversed compared with the spontaneous activity (Fig. 4 A). During external pacing, the Ca2+ increases first at the SL side when AP-activated Ca2+ intrudes to the cytosol (Fig. 4 A). This Ca2+ diffuses through the cytosol to the sub-SR region and activates CICR via RyR. The overlay of the INCX during spontaneous and externally evoked activity reveals a depolarizing “hump” in the INCX curve that activates the AP during spontaneous Ca2+ oscillations, but which is naturally not present in the INCX curve during external pacing (Fig. 4 B).

Figure 4.

Calcium fluxes during spontaneous and stimulated activity. (A) Simulated spontaneous APs followed by simulated electrically evoked APs (bottom) with corresponding near-SR and near-SL calcium signals (top). (B) The difference in the INCX during spontaneous and electrically evoked activity. Arrows show the prominent inward current during spontaneous activity, which is absent during electrically evoked APs. (C) The net Ca2+ fluxes from the SR to cytosol (top) and from the extracellular space to cytosol (bottom). The left column shows the fluxes during spontaneous activity, and the right column shows them during the electrically evoked activity. The integrals of the positive and negative phases are indicated with arrows. The concentrations are in the volume of the cytosol.

The difference between spontaneous and paced activity can also be seen from the net SL and SR fluxes (Fig. 4 C). This naturally results from the fact that during the spontaneous activity, the Ca2+ is first released from the SR side, whereas during the paced activity the Ca2+ release occurs first at the SL side. The released amounts of Ca2+ from both sides of the cytosol are taken up during relaxation. This produces net integrals of zero for the SR and SL Ca2+ fluxes over one cycle of activity, and thus the Ca2+ homeostasis is maintained in the model (Fig. 4 C). During spontaneous activity, the net SL Ca2+ flux extrudes 1.1 μM of Ca2+ when NCX triggers the AP. The voltage-activated Ca2+ channels ICaL along with the minor contribution of ICaT, ICab, and INCX reverse mode (Ca2+ intrusion mode) together provide sufficient Ca2+ intrusion, compensating for the Ca2+ extrusion by NCX during activation of the AP. This compensation prevents the depletion of SR Ca2+ and cessation of the spontaneous activity in E9-E11 cardiomyocytes as we described in Rapila et al. (2008).

Simulations with our model produce [Ca2+]i, [Na+]i, and [K+]i values that are physiologically coherent (Table I) (Bers, 2001), and the r.p. and AP amplitude values are also comparable to experimental data (Table I) (Rapila et al., 2008). In the experiments, we also estimated the fractional Ca2+ release by comparing the amplitude of the twitch Ca2+ transient, which equals the sum of calcium fluxes from the SR and the SL to cytosol, to the amplitude of the caffeine-induced Ca2+ transient, which represents the whole SR Ca2+ content. By comparing the twitch Ca2+ transient to the caffeine-induced transient, it was calculated that during a spontaneous calcium transient, the SR and SL sources produce Ca2+ intrusion, which is 56.5 ± 0.5% compared with the total SR Ca2+ content (Rapila et al., 2008). The corresponding simulated value for Ca2+ intrusion from SL and SR sources versus SR Ca2+ content during activation of spontaneous twitch is 70% (Table I and Fig. 4 C).

TABLE I.

Parameters of the Simulation Results

| Simulated parameter | Spontaneous | Pacing |

|---|---|---|

| [Na+]i diastolic (mM) | 13.5 | 13.8 |

| [K+]i diastolic (mM) | 142.4 | 142.2 |

| r.p. mean (mV) | −68.5 | −68.3 |

| AP amplitude (mV) | 78.7 | 82.9 |

| [Ca2+]i diastolic (μM) | ||

| Near SL (0.5 μm) | 0.17 | 0.19 |

| Near SR (0.5 μm) | 0.12 | 0.10 |

| Ca2+ transient amplitude (μM) | ||

| Near SL (0.5 μm) | 0.73 | 0.46 |

| Near SR (0.5 μm) | 1.4 | 1.6 |

| SR Ca2+ content in cytosol volume (μM) |

19.3 | 16.9 |

It has been reported that embryonic cardiomyocytes have a smaller cytosolic Ca2+ buffering capacity per cytosol volume than adult cardiomyocytes (Creazzo et al., 2004). Taking this into account in the model, smaller Ca2+ cycling per cytosol volume between the cytosol and Ca2+ sources (SR and the extracellular space) is required to produce contraction and relaxation. In the embryonic cardiomyocyte, the amount of cycled Ca2+ (i.e., the net Ca2+ release to cytosol) during a spontaneous twitch in cytosol volume is 9.6 − 1.1 + 5.0 = 13.5 μM (Fig. 4 C), which is 35% of that in the adult mouse ventricular myocyte (39 ± 3 μM) (Maier et al., 2003). Furthermore, the diastolic SR Ca2+ content in cytosol volume in the spontaneously beating embryonic cardiomyocyte is 19.3 μM (Table I), which is ∼14% of that in the adult mouse ventricular myocyte (142 ± 9 μM) (Maier et al., 2003). To make a reasonable comparison, the Ca2+ concentrations above are in the cytosol volume of the corresponding cell type to normalize the effect of different cell size between adult and embryonic cardiomyocytes.

The mode for spontaneous Ca2+ oscillations and the mode for AP-induced Ca2+ transients can be separated on the basis of their resting potential boundaries. We simulated the spontaneous and externally paced activity of the model cell while adjusting the membrane voltage with constant current injection. We found that spontaneous calcium release can operate at relatively depolarized membrane potentials between −88 to −27 mV, whereas AP-induced CICR is recruited between −107 to −38 mV (Fig. 5). The spontaneous activity cannot operate at r.p. values below −88 mV because hyperpolarization increases Ca2+ extrusion via NCX and thereby depletes the SR Ca2+ content. On the other hand, the externally triggered AP-driven mode cannot operate at r.p. values above −38 mV because depolarization inactivates the voltage-activated Ca2+ channels in the SL. Below −70 mV, 1 Hz pacing is not possible because longer diastole is required to refill the SR due to the higher Ca2+ extrusion via NCX. On the other hand, above −70 mV the cell cannot be synchronized to pacing frequencies 0.25 and 0.5 Hz because the frequency of the spontaneous activity is higher. This is in line with our suggestion (Rapila et al., 2008) that the activity in tissue is synchronized to the cell with the highest frequency.

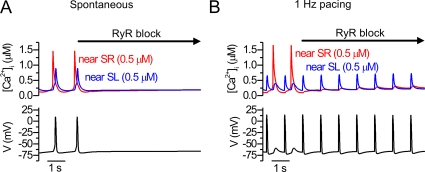

The spontaneous Ca2+ and Vm activities of the E9-E11 mouse cardiomyocytes rely on the cytosolic Ca2+ oscillations originating from the SR (Rapila et al., 2008). Similarly in our model, the inhibition of RyR stopped the spontaneous Ca2+ oscillations and APs (Fig. 6 A). Also in line with experimental results (Rapila et al., 2008), the model cell without functional RyRs was still able to produce SL-originated Ca2+ signals and APs with external pacing (Fig. 6 B). The amplitude of these Ca2+ signals was reduced when the RyRs were inhibited in simulation and experiments (Rapila et al., 2008) to 42.3 versus 32.5 ± 2.3% (average cytosolic Ca2+ transient), respectively, as no CICR occurred. Just like in the experiments (Rapila et al., 2008), the block of either SERCA or IP3R both stopped the spontaneous activity while the electrical excitability was maintained (Fig. S1, available at http://www.jgp.org/cgi/content/full/jgp.200809961/DC1). Based on these simulations, the ion current types and densities recorded from E9-E11 myocytes (Fig. 2) are incapable of producing Vm oscillations without an intracellular Ca2+ stimulus or external electrical excitation. For spontaneous Ca2+ oscillations, all three SR Ca2+ handling components are required. Without SERCA the SR Ca2+ stores are depleted, without RyRs the IP3Rs cannot produce transient Ca2+ signals, and without IP3Rs the RyRs are not activated without a sufficient cytosolic Ca2+ trigger.

Figure 6.

Simulated effect of RyR block. The near-SL and near-SR cytosolic [Ca2+] and APs are shown from simulations of (A) spontaneous and (B) electrically excited activity. The RyR block was applied after three control E–C coupling cycles.

To further validate the function of the SR and the dynamics of RyRs and IP3Rs, we simulated the cytosolic Ca2+ under pharmacological stimulation of these receptors as in our experiments (Rapila et al., 2008). In the presence of IP3R block, the simulated effect of caffeine, which rapidly opens the RyRs, produces a rapidly activating large Ca2+ transient (Fig. 7 A). The amplitudes of the sub-SR and sub-SL caffeine-induced Ca2+ transients are ∼1.5-fold compared with normal spontaneous Ca2+ transients. In contrast to this, the simulated effect of the applied IP3-AM stimulating the IP3R with RyR block produces only an increasing Ca2+ leak via IP3R, which slowly increases the diastolic [Ca2+]i (Fig. 7 B). Both of these simulations are in line with our experiments (Rapila et al., 2008) and with our previous conclusions that the RyR is the only possible route for transient Ca2+ release in these cells, but the IP3R plays a role as a stimulator of RyR.

Figure 7.

Simulated stimulation of RyR and IP3R. (A) The combined effect of caffeine (see Materials and methods) and IP3R block was simulated during simulation of spontaneous activity. (B) The combined effect of IP3-AM increasing the [IP3] slowly (see Materials and methods) and RyR block was simulated during simulation of spontaneous activity. For A and B, the near-SL and near-SR cytosolic [Ca2+] are shown. (C) The steady-state spontaneous AP frequency versus [IP3] (circles) with a sigmoidal fit to the data (solid line). When increasing [IP3] to values of 0.08 μM and above, arrhythmias were observed increasingly. (D) The experimentally recorded distribution of the frequencies of the spontaneous activity in E9-E11 mouse cardiomyocytes (n = 94). The raw data are from Rapila et al. (2008).

To support our conclusion that IP3R Ca2+ leak stimulates RyR openings, we showed that stimulation of IP3Rs with IP3-AM increases the frequency of spontaneous activity (Rapila et al., 2008). This same regulatory mechanism is reproduced in our model (Fig. 7 C). In the simulations, the oscillation frequency showed sigmoidal dependence on the [IP3]. The possible oscillation frequencies achieved with [IP3] regulation in the model cell were in the range of ∼0.2 to 1.1 Hz. In the experiments (Rapila et al., 2008), the frequencies of the spontaneous activities (global cytosolic Ca2+ transients and APs) were all within the range of 0.1 to 1.3 Hz (Fig. 7 D). This supports the idea that the dynamics and the structure of SR in the model are comparable to those in real E9-E11 cardiomyocytes. Modeling also supports the conclusions drawn from the experiments and demonstrates that in theory [IP3] could act as a major regulator of the embryonic heart beat frequency.

Model Predictions of the Embryonic Pacemaking and E–C Coupling Defects

During the early embryonic cardiac development, genetic disruption of the ion channel proteins regulating excitability (Stieber et al., 2003) or calcium influx (Weissgerber et al., 2006) as well as proteins involved in cardiomyocyte calcium handling (Takeshima et al., 1998; Wakimoto et al., 2000) lead to drastic changes in calcium signaling and heart rate, with a consequent increase in embryonic lethality. We have shown (Figs. 3, 4, 6, and 7) that our model reproduces faithfully the normal features of the Ca2+ signaling and excitability of E9-E11 myocytes. For further validation of our mathematical model, we tested if our model reproduces and explains the functions of the cardiomyocytes from genetically engineered mouse models previously reported to have compromised embryonic E–C coupling and/or pacemaking.

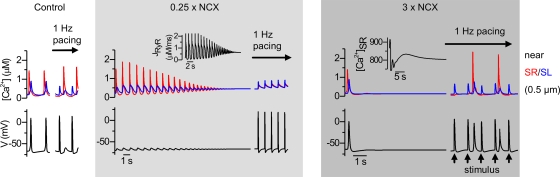

The hyperpolarization-activated cardiac “pacemaker” current If is encoded by three genes, HCN1, HCN2, and HCN4 (Yasui et al., 2001). It has been suggested that If is responsible for generating the spontaneous activity in embryonic ventricular cardiomyocytes (Yasui et al., 2001) as well as in specialized pacemaker cells (Stieber et al., 2003). Genetic ablation of the HCN4 reduces If in E10.5 mouse cardiomyocytes by ∼75%, with concomitant slowing of the heart rate by ∼35%, leading to embryonic lethality without structural anomalies between E9.5 to 11.5 (Stieber et al., 2003). In the model, reduction of the If from its the normal, measured density slows down the frequency of the spontaneous Ca2+ signals and APs, in line with the results from HCN4−/− cardiomyocytes (Stieber et al., 2003) (Fig. 8, A and B). On the other hand, up to twice an increase of If has very little effect on the spontaneous rate of the individual myocyte, although it suppresses the amplitude of the APs (Fig. 8, A and B). Our experiments (Fig. 2 B) (Rapila et al., 2008) and modeling (Figs. 6 and 8 A) indicate that neither If current density nor the voltage activation range (∼−70 mV threshold) of embryonic If is sufficient for initiating spontaneous Vm oscillations and APs at the resting potential (−57.2 ± 0.9 mV) (Rapila et al., 2008) of E9-E11 myocytes. However, the current density affects the excitability of the membrane by two additional mechanisms (Fig. 8, B and C), which might contribute to the phenotype of HCN4−/− mice hearts. First, If current is partly carried by Na+ ions; therefore, the If current density will effect the cytosolic [Na+] and consequently modulate the NCX current, which will be augmented at lower If densities (lower [Na+]i) and suppressed at higher If densities (higher [Na+]i) (Fig. 8 B). Second, because If is one of the depolarizing currents in embryonic myocytes, reduction of the current density will affect the excitability and the resting potential of the membrane (Fig. 8 C). Even though our experiments and modeling do not suggest a central role for If in developing E9-E11 ventricular myocytes, these results do not rule out the possibility that when the true pacemaker cells develop, the If current would have a central role in regulating the embryonic heartbeat. Interestingly, it has been suggested that also in fully developed pacemaker cells this SR-originated activity could contribute to the spontaneous activity (Bogdanov et al., 2001).

Figure 8.

The simulated effect of genetic modification of the If. (A) Simulated effects of ablation (0.25×) and overexpression (2×) of If. The near-SL and near-SR cytosolic [Ca2+] and APs are shown during spontaneous activity, which is followed by an application of SR Ca2+ flux block and 1-Hz electrical excitation. (B) Relative changes in [Na+]i and spontaneous beating frequency by altered If expression. Insert shows the INCX with different If expression levels (0.25×, 1×, and 2×). (C) 3-D plot of the effect of varying If current density on the excitability and AP amplitude at different resting potentials.

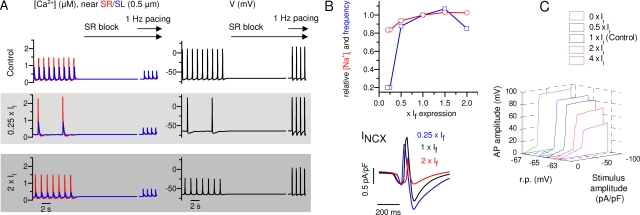

According to our experiments (Rapila et al., 2008), the NCX has a crucial role in embryonic cardiomyocytes in linking the spontaneous calcium activity with the membrane voltage. Therefore, it is not a surprise that ablation of the cardiac NCX isoform NCX1 results in embryonic lethality before E10, severe cardiomyocyte malformations, and lack of spontaneous heartbeats (Wakimoto et al., 2000). In line with the function of E9.5 NCX1−/− in mouse cardiac myocytes, our model predicts that lack of NCX activity prevents triggering of the AP and decreases the spontaneous activity due to cytosolic calcium accumulation, incapacitating the calcium release. Although mouse embryos with targeted inactivation of NCX1 lack spontaneous heartbeats, cardiomyocytes isolated from NCX1-null embryos are still excitable and generate Ca2+ signals when electrically stimulated (Koushik et al., 2001). In line with this, model cells with reduced NCX current density generate cytosolic Ca2+ transients when stimulated, but during pacing calcium accumulates in the cytosol because of the reduced calcium extrusion capacity (Fig. 9). On the other hand, overexpression of NCX also inhibits spontaneous activity by depleting the calcium stores, but additionally leads to a hyperexcitable membrane and arrhythmias during external pacing (Fig. 9).

Figure 9.

Effects of varying INCX density on the simulated calcium signals and membrane voltage of embryonic cardiomyocytes. Decreased INCX (0.25× control) causes cytosolic calcium accumulation and stops the spontaneous activity (middle) by altering calcium flux through RyRs (JRyR, insert). Upon simulated external electrical stimulation, the model produces cytosolic calcium transients and APs, where calcium transients rely on calcium flux through voltage-activated calcium channels. Increased INCX (3× control) enhances calcium extrusion, depleting the SR calcium stores (insert), thus stopping the spontaneous activity. The model cell retains its excitability, but due to lower [Ca2+]i levels facing RyRs, calcium influx can only induce sporadic SR calcium releases, thus causing irregular activity (right panels).

One of the few genetic models highlighting the role of the intracellular calcium stores during cardiac development is the mouse model lacking calreticulin (Mesaeli et al., 1999), a ubiquitous SR Ca2+ buffer expressed in cardiac myocytes during embryonic development. Ablation of the calreticulin gene is lethal before E18 due to severe cardiac malformation and impaired function (Mesaeli et al., 1999). In our model, the simulated reduction of calreticulin reduces the SR Ca2+ buffering and release, eventually stopping the spontaneous activity (Fig. 10 A). Overexpression of calreticulin has been reported to cause lower heart rate during embryonic development and cardiac failure and sudden cardiac death during postnatal development (Nakamura et al., 2001). In our model, the simulated overexpression results similarly in a reduced frequency of the spontaneous calcium releases with increases in released and SR Ca2+ (Fig. 10 A). These experimental findings (Mesaeli et al., 1999; Nakamura et al., 2001) and our simulations predict that the relationship between the amount of calreticulin and the spontaneous beating rate is a bell-shaped curve (Fig. 10 B). With both reduced and increased calreticulin content, membrane excitability and voltage-activated calcium influx are retained. However, with calreticulin overexpression, CICR is enhanced due to increased SR calcium content and release, which leads to arrhythmic spontaneous calcium releases and APs between stimulated APs.

Figure 10.

Effects of varying calreticulin Ca2+ buffer in SR on the simulated calcium signals and membrane voltage of embryonic cardiomyocytes. (A) Ablation of SR calreticulin content inhibits the spontaneous activity and reduces the stimulated calcium signals (middle row), whereas increased calreticulin content (1.5× control) lowers the frequency but increases the amplitude of both spontaneous and stimulated calcium signals. During stimulated APs, spontaneous calcium releases ensue due to overly large SR calcium content. (B) Effect of SR calreticulin content on the relative spontaneous frequency (f/fcontrol, Hz) of APs in the model cell.

DISCUSSION

Here, we present a mathematical model of E–C coupling and pacemaking of E9-E11 mouse ventricular cardiomyocytes. The model explains how these two separate modes for producing Ca2+ signals, the spontaneous activity originating from the SR triggering APs via NCX and the externally initiated AP-driven activity triggering CICR, coexist in individual cardiomyocytes. In addition to normal myocyte function, our mathematical model elucidates the E–C coupling and underlying mechanisms of the phenotypes of genetically engineered embryonic mouse models. Based on this validation, our mathematical model is the first comprehensive description of how the embryonic heartbeats are generated and regulated in E9-E11 cardiomyocytes.

Limitations of the Model

The delay from SR Ca2+ release to AP upstroke is larger in our model than in the experiments (Rapila et al., 2008). This is due to the approximation of the shape of the model cell to a sphere with radial symmetry. The dimensions of real cells are more similar to a flat ellipsoid. Consequently, there is variability in the diffusion distance between SL and SR and in the diffusion restriction in different parts of the cell. The local Ca2+ concentrations and consequently INCX are thus larger in parts of real cells, resulting in faster activation of the AP than in our model. In a more realistic ellipsoid-shaped model cell, the description of the diffusion would require three coordinates. The [Ca2+] would have spatial differences in directions parallel to the SL and SR surfaces, and the function of Ca2+ transporting ion channels would need to be calculated separately in all points of the SL and SR surface grid. This would increase the computational cost exponentially and severely limit the practical usability of the model. Our model is capable of explaining the embryonic E–C coupling and pacemaking mechanisms and underlying mechanisms of several genetically engineered embryonic mice. The spherical shape is thus a fair compromise between computational efficiency and the validity of our model.

The Simulated Ca2+ Oscillations in E9-E11 Cardiomyocytes

The spontaneous Ca2+ oscillations between cytosol and SR/ER have been modeled previously in other cell types than cardiac myocytes (Deyoung and Keizer, 1992; Keizer and Levine, 1996; Sneyd et al., 2003). The models have included the Ca2+-ATPase pump and IP3R (Deyoung and Keizer, 1992) or RyR (Keizer and Levine, 1996) or both of these receptors (Sneyd et al., 2003), as Ca2+ routes between the SR/ER and cytosol. These models produce cytosolic Ca2+ oscillations at the rate of ∼0.1–0.01 Hz (Deyoung and Keizer, 1992; Keizer and Levine, 1996; Sneyd et al., 2003), whereas the spontaneous Ca2+ oscillations in the E9-E11 cardiomyocytes had a frequency of ∼0.1–1.3 Hz (Rapila et al., 2008). Here, we showed with modeling that this rapid oscillation (∼1 Hz) can also be theoretically produced by the combined activity of RyRs, IP3Rs, and SERCA (Fig. 3). The basis of this activity is the [IP3]-dependent IP3R Ca2+ leak, which triggers the large Ca2+ releases via RyR (Figs. 3 and 7) and thereby increases the endogenously low spontaneous opening rate of RyRs (Keizer and Levine, 1996). Thus, as in the experiments (Rapila et al., 2008), the magnitude of the IP3R Ca2+ leak regulates the frequency of the Ca2+ oscillations and APs triggered by this oscillation.

In line with our experiments (Rapila et al., 2008), the RyR, IP3R, and SERCA all play obligatory roles in producing oscillations (Fig. 6 and Fig. S1). However, as long as all of these components are present to some extent, the oscillation seems to be robust, as it was maintained even with ± 25% change in the amount of RyR, IP3R, or SERCA (unpublished data). The cardiac myocytes undergo dramatic changes during development; therefore, the SR-originated oscillation might be a stable backup that guarantees the cell's capability to maintain its activity in these varying conditions.

Electrophysiology of the E9-E11 Cardiomyocytes

Here, we presented the first complete characterization of membrane ion currents in E9-E11 mouse ventricular cardiomyocytes (Fig. 2). Based on our simulations and experiments (Rapila et al., 2008), the NCX is the most crucial ion current regulating the activity of the embryonic cardiomyocytes. In E9-E11 cardiomyocytes, the INCX triggers membrane depolarization during spontaneous activity and regulates the r.p. and intracellular [Ca2+] (Table I and Figs. 3 and 4). These multiple roles of INCX explain the severe dysfunctions in the simulated E–C coupling and pacemaking with altered amounts of functional NCX (Fig. 9) and the embryonic lethality of the embryos lacking NCX1 (Wakimoto et al., 2000).

It has been suggested that If generates the spontaneous activity in embryonic cardiomyocytes (Stieber et al., 2003). Although we found a significant amount of If from E9-E11 myocytes, results in this and our accompanying paper in this issue suggest that the If does not initiate the spontaneous activity in E9-E11 cardiomyocytes. The pharmacological inhibition of the If in the experiments (Rapila et al., 2008) and the simulated overexpression and down-regulation of the If did not stop the rhythmic Ca2+ activity triggering the contraction and APs via NCX. The If in E9-E11 cardiomyocytes shows a significant active current only at membrane voltages lower than r.p. (Fig. 2 B); thus, even a doubled amount of current in E9-E11 myocytes cannot generate spontaneous APs (Fig. 8 A). Similarly to If, we found a small amount of functional T-type Ca2+ channel current in E9-E11 cardiomyocytes (Fig. 2). The specific method to measure T-type current would have been recording it as an Ni2+-sensitive current (Furukawa et al., 1992). However, the T-type current was separated sufficiently from the L-type current based on voltage clamps from different holding potentials as described previously (Niwa et al., 2004).

According to model simulations, the modes for spontaneous Ca2+ oscillations and AP-induced Ca2+ transients can be separated on the basis of their resting potential boundaries (Fig. 5). We found that spontaneous calcium release can operate effectively at relatively depolarized membrane potentials, whereas AP-induced CICR is favored when the membrane potential is more hyperpolarized. This difference between the excitation modes in respect to their r.p. boundaries may represent the order of recruitment of these modes during development because the cardiomyocyte resting potential hyperpolarizes during the progress of fetal development (Reppel et al., 2007). During cell migration in early development the cells are isolated from others (Buckingham et al., 2005), and even with depolarized r.p., their spontaneous activity guarantees that their activity is maintained. Later during development, the cells with more negative r.p. values form a stable tissue wherein the phenotype is shaped toward that of nonspontaneously active adult ventricular cardiomyocytes, which form coordinated contraction induced by an external stimulus (Kamino, 1991). Also, it is energetically cheaper not to provide the AP-driven mode until it is required for efficient and more coordinated contraction because based on our simulations, maintaining a hyperpolarized r.p. requires larger NaK-ATPase activity and therefore induces a higher ATP consumption rate (unpublished data).

Regulation of the Embryonic E–C Coupling and Heartbeat

The physical structure of E9-E11 cells sets boundary conditions for the E–C coupling and pacemaking. The lack of T tubules in E9-E11 myocytes results in loose coupling between SR and SL ion channels and other components. This limits the possible heartbeat frequency because a certain time is required for Ca2+ diffusion between SR and SL. Furthermore, any alterations in the shape and the size of the cytosol affect the dynamics of the cytosolic Ca2+ signals, further modulating the heartbeat frequency. Due to the lack of T tubules and loose spatial coupling between ICaL and RyR, a relatively large SL Ca2+ intrusion is required for a strong enough Ca2+ signal to diffuse through the cytosol and initiate CICR from SR. In the adult mouse ventricular myocyte, with tight ICaL and RyR coupling, only ∼10% of total cytosolic Ca2+ intrusion originates from SL and ∼90% from SR during CICR (Maier et al., 2003). Our simulations suggest that during AP-induced CICR, ∼42% of cytosolic Ca2+ intrusion occurs from the SL and ∼58% from the SR (Fig. 4 C). In addition, our results suggest that a strong SR function is essential for spontaneous activity in embryonic cardiomyocytes as well as for synchronizing the contractile activity via the AP-driven mode.

On the basis of our results, several contributing mechanisms for the regulation of the beating rate of the embryonic hearts can be suggested. In general, because the spontaneous activity originates solely from the single cell and it is not controlled by any outside triggering mechanism, several parameters within the cell may affect the rate of activity. A dynamic regulation in the time scale of seconds could be addressed via regulation of the activity of IP3Rs, RyRs, and SERCA. One example of the direct modulation would be the [IP3], which was shown here to strongly regulate the cardiomyocyte beating frequency (Fig. 7). The upper boundary of the [IP3]-dependent beating frequency is limited because the increment of [IP3] also depletes the SR Ca2+ required for spontaneous releases. Subsequently, the relationship between cardiomyocyte beating frequency and [IP3] is a bell-shaped curve. The activity of SERCA could modulate heart rate because altering the refilling velocity of the SR alters the kinetics of the relaxation phase of the Ca2+ oscillation as well as Ca2+ leak through IP3Rs. Based on this, it is possible in theory that the dynamic regulatory mechanisms directly or indirectly affecting SERCA function, such as the β-adrenergic pathway, will regulate heart rate by modulating the SR Ca2+ uptake. In a slower time scale, the heartbeat could be obviously regulated by altering the expression levels of RyR, IP3R, and SERCA as well as calreticulin (Fig. 10 B). The SL ion channels also affect the heart rate. They may contribute directly, such as ICaL and INCX, or indirectly, such as the If (Fig. 8), to the kinetics of Ca2+ fluxes at the SL and furthermore to the SR Ca2+ content and dynamics.

Here, we have presented a characterization and a mathematical model of E–C coupling and pacemaking in early embryonic (E9-E11) mouse ventricular cardiomyocytes. To develop the model, we presented novel approaches in cardiomyocyte modeling. The model includes an implementation of a noncommon pool cytosol and oscillatory SR dynamics incorporated with SL ion current dynamics as characterized in our experiments. The model explains the underlying mechanisms behind the functional dualism of these cells (Rapila et al., 2008). The model reproduces the SR-driven spontaneous activity and the AP-driven externally evoked activity. The model also elucidates the mechanisms behind the altered E–C coupling and pacemaking in genetically modified embryos. The current understanding of the embryonic cardiomyocyte E–C coupling and pacemaking is shaped by the suggestions of the underlying mechanisms based on experimental results, which so far have been controversial. This study shows by mathematical modeling how several of the suggested mechanisms can operate in parallel to control the initiation and regulation of the embryonic heartbeat.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank SL. Hänninen for valuable comments on the manuscript and A. Rautio for technical assistance.

This study was supported by the Finnish Heart Research Foundation, Academy of Finland, and Sigrid Juselius Foundation.

Olaf S. Andersen served as editor.

Abbreviations used in this paper: AP, action potential; E–C, excitation–contraction; ICaL, L-type Ca2+ current; ICaT, T-type Ca2+ current; If, hyperpolarization-activated current; IK1, time-independent background K+ current; IKDR, slowly activated delayed rectifier K+ current; INa, fast Na+ current; IP3R, inositol-3-phosphate receptor; NCX, Na+/Ca2+ exchanger; r.p., resting potential; RyR, ryanodine receptor; SERCA, SR Ca2+ ATPase; SL, sarcolemmal.

References

- Atri, A., J. Amundson, D. Clapham, and J. Sneyd. 1993. A single-pool model for intracellular calcium oscillations and waves in the Xenopus laevis oocyte. Biophys. J. 65:1727–1739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bers, D.M. 2001. Excitation-Contraction Coupling and Cardiac Contractile Force. Kluwer, Dordrecht, London. 427 pp.

- Bogdanov, K.Y., T.M. Vinogradova, and E.G. Lakatta. 2001. Sinoatrial nodal cell ryanodine receptor and Na+-Ca2+ exchanger: molecular partners in pacemaker regulation. Circ. Res. 88:1254–1258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bondarenko, V.E., G.P. Szigeti, G.C.L. Bett, S.J. Kim, and R.L. Rasmusson. 2004. Computer model of action potential of mouse ventricular myocytes. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 287:H1378–H1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckingham, M., S. Meilhac, and S. Zaffran. 2005. Building the mammalian heart from two sources of myocardial cells. Nat. Rev. Genet. 6:826–835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creazzo, T.L., J. Burch, and R.E. Godt. 2004. Calcium buffering and excitation-contraction coupling in developing avian myocardium. Biophys. J. 86:966–977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cribbs, L.L., B.L. Martin, E.A. Schroder, B.B. Keller, B.P. Delisle, and J. Satin. 2001. Identification of the T-type calcium channel (Ca(V)3.1d) in developing mouse heart. Circ. Res. 88:403–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cussler, E.L. 1997. Diffusion: Mass Transfer in Fluid Systems. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. 580 pp.

- Debetto, P., F. Cusinato, and S. Luciani. 1990. Temperature-dependence of Na+/Ca2+ exchange activity in beef-heart sarcolemmal vesicles and proteoliposomes. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 278:205–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Despa, S., F. Brette, C.H. Orchard, and D.M. Bers. 2003. Na/Ca exchange and Na/K-ATPase function are equally concentrated in transverse tubules of rat ventricular myocytes. Biophys. J. 85:3388–3396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deyoung, G.W., and J. Keizer. 1992. A single-pool inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate-receptor-based model for agonist-stimulated oscillations in Ca2+ concentration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 89:9895–9899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doevendans, P.A., S.W. Kubalak, R.H. An, K.D. Becker, K.R. Chien, and R.S. Kass. 2000. Differentiation of cardiomyocytes in floating embryoid bodies is comparable to fetal cardiomyocytes. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 32:839–851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dokos, S., B. Celler, and N. Lovell. 1996. Ion currents underlying sinoatrial node pacemaker activity: a new single cell mathematical model. J. Theor. Biol. 181:245–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank, K., C. Tilgmann, T.R. Shannon, D.M. Bers, and E.G. Kranias. 2000. Regulatory role of phospholamban in the efficiency of cardiac sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ transport. Biochemistry (Mosc.). 39:14176–14182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furukawa, T., H. Ito, J. Nitta, M. Tsujino, S. Adachi, M. Hiroe, F. Marumo, T. Sawanobori, and M. Hiraoka. 1992. Endothelin-1 enhances calcium entry through T-type calcium channels in cultured neonatal rat ventricular myocytes. Circ. Res. 71:1242–1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagar, R.E., and B.E. Ehrlich. 2000. Regulation of the type III InsP(3) receptor by InsP(3) and ATP. Biophys. J. 79:271–278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagar, R.E., A.D. Burgstahler, M.H. Nathanson, and B.E. Ehrlich. 1998. Type III InsP3 receptor channel stays open in the presence of increased calcium. Nature. 396:81–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart, G. 1983. The kinetics and temperature dependence of the pace-maker current if in sheep Purkinje fibres. J. Physiol. 337:401–416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hille, B. 2001. Ion Channels of Excitable Membranes. Sinauer Associates, Sunderland, MA. 818 pp.

- Jafri, M.S., J.J. Rice, and R.L. Winslow. 1998. Cardiac Ca2+ dynamics: the roles of ryanodine receptor adaptation and sarcoplasmic reticulum load. Biophys. J. 74:1149–1168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamino, K. 1991. Optical approaches to ontogeny of electrical-activity and related functional-organization during early heart development. Physiol. Rev. 71:53–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keizer, J., and L. Levine. 1996. Ryanodine receptor adaptation and Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release-dependent Ca2+ oscillations. Biophys. J. 71:3477–3487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korhonen, T., and P. Tavi. 2008. Automatic time-step adaptation of the forward Euler method in simulation of models of ion channels and excitable cells and tissue. Simul. Model. Pract. Theory. 16:639–644. [Google Scholar]

- Koushik, S.V., J. Wang, R. Rogers, D. Moskophidis, N.A. Lambert, T.L. Creazzo, and S.J. Conway. 2001. Targeted inactivation of the sodium-calcium exchanger (Ncx1) results in the lack of a heartbeat and abnormal myofibrillar organization. FASEB J. 15:1209–1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo, C.H., and Y. Rudy. 1994. A dynamic-model of the cardiac ventricular action-potential. 1. Simulations of ionic currents and concentration changes. Circ. Res. 74:1071–1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maier, L.S., T. Zhang, L. Chen, J. DeSantiago, J.H. Brown, and D.M. Bers. 2003. Transgenic CaMKII delta(C) overexpression uniquely alters cardiac myocyte Ca2+ handling: reduced SR Ca2+ load and activated SR Ca2+ release. Circ. Res. 92:904–911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mery, A., F. Aimond, C. Menard, K. Mikoshiba, M. Michalak, and M. Puceat. 2005. Initiation of embryonic cardiac pacemaker activity by inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate-dependent calcium signaling. Mol. Biol. Cell. 16:2414–2423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesaeli, N., K. Nakamura, E. Zvaritch, P. Dickie, E. Dziak, K.H. Krause, M. Opas, D.H. MacLennan, and M. Michalak. 1999. Calreticulin is essential for cardiac development. J. Cell Biol. 144:857–868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura, K., M. Robertson, G. Liu, P. Dickie, K. Nakamura, J.Q. Guo, H.J. Duff, M. Opas, K. Kavanagh, and M. Michalak. 2001. Complete heart block and sudden death in mice overexpressing calreticulin. J. Clin. Invest. 107:1245–1253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niwa, N., K. Yasui, T. Opthof, H. Takemura, A. Shimizu, M. Horiba, J.K. Lee, H. Honjo, K. Kamiya, and I. Kodama. 2004. Ca(v)3.2 subunit underlies the functional T-type Ca2+ channel in murine hearts during the embryonic period. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 286:H2257–H2263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandit, S.V., R.B. Clark, W.R. Giles, and S.S. Demir. 2001. A mathematical model of action potential heterogeneity in adult rat left ventricular myocytes. Biophys. J. 81:3029–3051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez, P.J., J. Ramos-Franco, M. Fill, and G.A. Mignery. 1997. Identification and functional reconstitution of the type 2 inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor from ventricular cardiac myocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 272:23961–23969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Politi, A., L.D. Gaspers, A.P. Thomas, and T. Hofer. 2006. Models of IP3 and Ca2+ oscillations: frequency encoding and identification of underlying feedbacks. Biophys. J. 90:3120–3133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puglisi, J.L., R. Bassani, J.W.M. Bassani, J.N. Amin, and D.M. Bers. 1996. Temperature and relative contributions of Ca transport systems in cardiac myocyte relaxation. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 39:H1772–H1778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puglisi, J.L., W.L. Yuan, J.W.M. Bassani, and D.M. Bers. 1999. Ca2+ influx through Ca2+ channels in rabbit ventricular myocytes during action potential clamp: influence of temperature. Circ. Res. 85:E7–E16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos-Franco, J., M. Fill, and G.A. Mignery. 1998. Isoform-specific function of single inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor channels. Biophys. J. 75:834–839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapila, R., T. Korhonen, and P. Tavi. 2008. Excitation–contraction coupling of the mouse embryonic cardiomyocyte. J. Gen. Physiol. 132:397–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reppel, M., P. Sasse, D. Malan, F. Nguemo, H. Reuter, W. Bloch, J. Hescheler, and B.K. Fleischmann. 2007. Functional expression of the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger in the embryonic mouse heart. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 42:121–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasse, P., J. Zhang, L. Cleemann, M. Morad, J. Hescheler, and B.K. Fleischmann. 2007. Intracellular Ca2+ oscillations, a potential pacemaking mechanism in early embryonic heart cells. J. Gen. Physiol. 130:133–144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seisenberger, C., V. Specht, A. Welling, J. Platzer, A. Pfeifer, S. Kuhbandner, J. Striessnig, N. Klugbauer, R. Feil, and F. Hofmann. 2000. Functional embryonic cardiomyocytes after disruption of the L-type alpha(1C) (Ca(v)1.2) calcium channel gene in the mouse. J. Biol. Chem. 275:39193–39199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shannon, T.R., F. Wang, J. Puglisi, C. Weber, and D.M. Bers. 2004. A mathematical treatment of integrated Ca dynamics within the ventricular myocyte. Biophys. J. 87:3351–3371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sneyd, J., and J.F. Dufour. 2002. A dynamic model of the type-2 inositol trisphosphate receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 99:2398–2403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sneyd, J., K. Tsaneva-Atanasova, J.I.E. Bruce, S.V. Straub, D.R. Giovannucci, and D.I. Yule. 2003. A model of calcium waves in pancreatic and parotid acinar cells. Biophys. J. 85:1392–1405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stieber, J., S. Herrmann, S. Feil, J. Loster, R. Feil, M. Biel, F. Hofmann, and A. Ludwig. 2003. The hyperpolarization-activated channel HCN4 is required for the generation of pacemaker action potentials in the embryonic heart. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 100:15235–15240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeshima, H., S. Komazaki, K. Hirose, M. Nishi, T. Noda, and M. Lino. 1998. Embryonic lethality and abnormal cardiac myocytes in mice lacking ryanodine receptor type 2. EMBO J. 17:3309–3316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakimoto, K., K. Kobayashi, M. Kuro-o, A. Yao, T. Iwamoto, N. Yanaka, S. Kita, A. Nishida, S. Azuma, Y. Toyoda, et al. 2000. Targeted disruption of Na+/Ca2+ exchanger gene leads to cardiomyocyte apoptosis and defects in heartbeat. J. Biol. Chem. 275:36991–36998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissgerber, P., B. Held, W. Bloch, L. Kaestner, K.R. Chien, B.K. Fleischmann, P. Lipp, V. Flockerzi, and M. Freichel. 2006. Reduced cardiac L-type Ca2+ current in Ca-v beta(−/−)(2) embryos impairs cardiac development and contraction with secondary defects in vascular maturation. Circ. Res. 99:749–757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinogradova, T.M., V.A. Maltsev, K.Y. Bogdanov, A.E. Lyashkov, and E.G. Lakatta. 2005. Rhythmic Ca2+ oscillations drive sinoatrial nodal cell pacemaker function to make the heart tick. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 1047:138–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasui, K., W. Liu, T. Opthof, K. Kada, J.K. Lee, K. Kamiya, and I. Kodama. 2001. I(f) current and spontaneous activity in mouse embryonic ventricular myocytes. Circ. Res. 88:536–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.