Abstract

The pelvic support osteotomy is a double level femoral osteotomy with the objective of eliminating a Trendelenburg and short limb gait in young patients with severe hip joint destruction as a consequence of neonatal septic arthritis. The osteotomy has seen several changes and a brief historical overview is provided to set the evolution of the modifications of the procedure in context. We present an analysis of the preoperative assessment that will assist the surgeon to plan out the procedure. Specifically, we set out to answer the following questions: (a) Where should the first osteotomy be performed and what is the magnitude of valgus and extension correction desired at this level? (b) Where should the second osteotomy be performed and what is the magnitude of varus and derotation desired at this level?

Keywords: Fixators, external; Ilizarov technique; Bone lengthening

Introduction

The pelvic support osteotomy is a useful surgical procedure for the salvage of damaged hips of patients in whom arthrodesis or hip arthroplasty are not appropriate. It is a procedure that has much to offer the adolescent or young adult who has painful limping, restriction of hip motion and early onset fatigue to walking as a consequence of hip destruction from neonatal septic arthritis or persistent severe hip dysplasia or dislocation. The surgery is a double-level osteotomy of the femur: (a) the more proximal valgus-extension osteotomy is performed with the femur in maximum adduction and at a level where the femoral shaft is seen to abut the pelvis; (b) the second, more distal, osteotomy restores the orientation of the knee and ankle joint lines in the coronal plane and also provides a focus for femoral lengthening if warranted. The proximal osteotomy lateralises and distally displaces the greater trochanter and in so doing increases the action of the abductor muscles. To this is added the elimination of any further adduction between femur and pelvis which then prevents pelvic drop during the single stance phase of gait. A successful pelvic support osteotomy reduces limp through abolishing the Trendelenburg lurch, equalises limb length and, through the stability provided to the hemipelvis, facilitates a more energy-efficient gait.

Historical

The term ‘pelvic support’ is attributed to Lance who, in 1936, used it in reference to subtrochanteric osteotomies for the treatment of congenital dislocation of the hip [1]. Variations of the procedure had been described, several pre-dating 1936, in which a medial displacement of the anatomical axis of the femur in relation to the mechanical axis produced increased stability [2]. Milch contrasted the ideologies behind the variations; some believed the angulation from the valgus osteotomy and consequent alteration of anatomical axis in relation to mechanical produced the desired effect of stability, in comparison to the view that abutment of the upper end of the osteotomised shaft of femur against the pelvis was responsible. The techniques by Lorenz [3], Schanz [4] and Ilizarov [5] deserve special mention. The subtrochanteric osteotomy designed by Lorenz was a valgus osteotomy coupled to a medial and proximal displacement of the shaft of femur (Fig. 1). The almost vertical disposition of the femoral shaft ‘supported’ the pelvis from abutment. However, the prominence of the displaced femoral shaft was noted by several authors to produce limitation of movement owing to the very same impingement against the lateral wall of the pelvis. This improved when the prominence remodelled with time or was surgically removed—interestingly, when the abutment was reduced pelvic stability was not lost in all cases. In contrast, the Schanz osteotomy (Fig. 1) was performed by introducing a valgus, and sometimes extension, position to the distal femoral segment but without the proximal displacement of the Lorenz procedure. Whilst this increased pelvic stability, it shared the same effect of abutment from the apex of angulation against the lateral wall of the pelvis, especially when the patient attempted to bring the widely abducted leg parallel to the opposite side. Both techniques therefore induced a limitation of movement from abutment. Milch highlighted this conundrum by introducing the concept of a post-osteotomy angle (angle β in Fig. 1, which is distinct from the angle of abduction at the level of the osteotomy) and its relation to pelvic inclination (angle α in Fig. 1) at the lateral wall of the ischium (Fig. 1). When this angle, whether from Schanz or Lorenz type osteotomies, exceeded pelvic inclination, impingement occurred when the patient attempted to bring the leg into parallel with the contralateral side [2]. The loss of parallelism was in effect an ‘abduction contracture’ and meant some patients, when standing, had to compensate with eversion of the foot and with tilting of the pelvis (consequently producing a relative adduction of the contralateral hip). Whilst this had the desired effect of eliminating the Trendelenburg gait (in which the pelvis tilts in the opposite direction), some surgeons erroneously increased the abduction angle (and consequently the post-osteotomy angulation) to such an excessive degree that it became a disability. Worse still, when the procedure was performed for bilateral cases this made compensation by pelvic tilting impossible [2]. Milch recommended this post-osteotomy angle should lie between 210° and 240°. In so doing, it made the procedure technically demanding as an excessive abduction angle (and correspondingly large post-osteotomy angle) produced stability at the expense of comfortable parallelism of both legs with a level pelvis, whereas one that was insufficiently abducted preserved movement but lost stability.

Fig. 1.

Both Lorenz and Schanz osteotomies provide ‘pelvic support’. Milch described a post-osteotomy angle (β) which predicted abutment against the lateral wall of the pelvis when it exceeded the angle of pelvic inclination (α). When the difference was excessive, restriction of movement was significant and created a secondary disability

The pelvic support osteotomy as described by Ilizarov provided a solution through a second, more distal, osteotomy. The significance of this additional osteotomy was to enable a proximal valgus osteotomy large enough to eradicate any degree of adduction in the hip (and thereby eliminate the Trendelenburg gait) but, through the distal varus osteotomy, achieve parallelism of both legs. If lengthening was performed through the distal osteotomy site, as was advocated by Ilizarov, parallelism of the both limbs with a level pelvis on standing was accomplished.

Indications

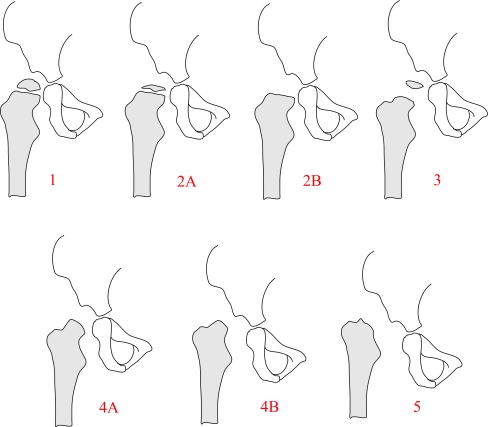

The sequelae for neonatal septic arthritis has been classified by Hunka et al. [6] (Fig. 2). Whilst the less severely affected varieties of types I to III are amenable to the more usual hip reconstruction procedures (either pelvic or femoral osteotomies or both), types IV and V, in which a greater part of the true hip is destroyed are, in effect, ‘pseudoarthroses’. A similar picture is seen in unsuccessfully treated or neglected cases of congenital dislocation of the hip and after a Girdlestone arthroplasty. In these scenarios the joint is unstable, allowing proximal migration of the femur on loading. This position weakens the action of the gluteal abductors through a shortening of the lever arm and produces the Trendelenburg gait [7]. The limp, although initially painless, becomes painful and walking tolerance decreases [7, 8] (Table 1).

Fig. 2.

Hunka described five types of sequelae from neonatal septic arthritis: 1 minimal or no femoral head changes; 2A femoral head deformity but physis intact; 2B femoral head deformity with physis closed; 3 femoral neck pseudoarthrosis; 4A complete destruction of femoral head but stable neck segment; 4B complete destruction of femoral head but unstable neck segment; 5 complete destruction of head and neck with dislocation

Table 1.

Indications for pelvic support osteotomy

| Indications | Detail description |

|---|---|

| Congenital hip dislocation | Neglected or unsuccessfully treated |

| Infantile and early childhood septic arthritis or osteomyelitis of the proximal femur | Hunka types 4 or 5 |

| Girdlestone resection arthroplasty due to failed previous reconstructive surgery or arthroplasty | Complete destruction of the head and neck to the intertrochanteric line |

| Traumatic hip dislocation with hip instability | If irretrievable by open reduction or total joint replacement |

| Femoral neck pseudarthrosis | If unsalvageable by classic techniques |

Proximal femoral migration also leads to an adduction contracture. Coupled to this is a posterior displacement of the femoral head; the centre of gravity of the body is then anterior to the femoral head and causes a ventral rotation of the pelvis, thereby increasing its anterior tilt. This, and the hip flexion contracture often seen in these patients, increase the compensatory lumbar lordosis and can be responsible for low back pain [6–8].

Alternative strategies

The problems arising from Hunka type IV or V hips are similar to those who have persistent dislocation of the hip, whether of congenital or traumatic aetiology. Surgery for an untreated congenital hip dislocation is difficult, especially when presentation is in the older child or adolescent. Most of the recommended reconstructive procedures designed to relocate the femoral head into an inadequate acetabulum and maintain coverage and containment do not address the issue of abductor insufficiency or of limb length discrepancy. Many authors report either unpredictable or poor results when attempts to relocate the hip are performed late, with hip stiffness being common.

The expectations of the patient population of today are for interventions to resolve lameness [9]. A recommendation for observation only is not readily accepted. Whilst arthrodesis remains a good solution for a degenerate, unstable, and painful joint, it is more likely to be used for smaller joints in the limb. An arthrodesis of the hip provides stability and complete pain relief but it has adverse effects on the lower back, contralateral hip and knee [10, 11]. Currently two appropriate treatment options for a deficient or unstable hip are total joint replacement or a pelvic support osteotomy [8, 9, 12].

Total joint replacement of a deficient hip is technically difficult with a significant complication rate of excessive shortening, sciatic or femoral nerve palsy, fracture of the femoral shaft, and early postoperative dislocation and aseptic loosening [12–14]. When correctly and successfully performed, it improves range of motion, gait symmetry and efficiency and provides excellent pain relief [12, 13]. However, even with current surgical techniques and prosthesis designs, a total hip replacement in young patients is still controversial [7, 15]. An active lifestyle can subject the joint replacement to high mechanical stresses rendering a likelihood of early implant loosening [8, 13, 14, 16]. Revision of a total hip arthroplasty in a patient with previous hip deficiency is often more difficult than a standard revision operation [12].

Relative contraindications

Rapid remodelling at the proximal femoral osteotomy site should be anticipated if the procedure is performed in young children (under the age of 12 years), with the loss of pelvic support occurring as early as 12 months after the procedure [17]. As such it is preferable to defer the procedure to after this age in order to avoid many repeat surgeries. Even when performed at the age of 12 years, a repeat procedure is likely to be needed at skeletal maturity. Accompanying the osteotomy remodelling potential is continued growth of the patient when treated at this age. This re-creates a leg length discrepancy by skeletal maturity, even if this was addressed at first surgery. Both loss of angulation at the osteotomy and a return of leg length discrepancy produce the limp again.

The procedure is also less suitable for older patients in who total hip replacements are a better alternative [7, 15]. Specific recommendations for a cut-off age are not possible at this time and much will depend on individual patient and surgeon circumstances, including resource allocations for health care.

Further contraindications are chronic paralytic hip dislocations (from neuromuscular disorders, e.g. cerebral palsy, myelomeningocele, poliomyelitis) in non-ambulating patients.

Planning from clinical assessment

A full assessment of the adolescent or young adult is mandatory and the answers to several important questions needed:

-

Is there an adduction contracture and what is the arc of abduction/adduction in the coronal plane? What is maximum adduction?

Some authors have described measuring this range by flexing the hip of the affected side over the unaffected. We recommend that contralateral hip be abducted over the edge of the examining couch (if this is possible) as this allows a better measure of adduction in the coronal plane. In the event of bilateral hip involvement and an inability to abduct the contralateral hip, a best estimate is then obtained by adducting and flexing one leg over the other.

A Trendelenburg gait arises from the patient thrusting the trunk over to the side of the weight-bearing limb in single stance in order to compensate for a pelvic obliquity that is produced from an unstable hip or hip abductor insufficiency. The pelvic obliquity in this case is equivalent to an adduction of that hip; this obliquity can be prevented by eradicating of any adduction at the hip in the single stance phase of gait. This is achieved through the proximal femoral osteotomy by placing the involved hip in maximum adduction. Therefore measuring maximum adduction is to provide a basis for the size of valgus osteotomy. It should be noted that many of these patients may have an adduction contracture as well. This needs to be added to the maximum range of adduction to arrive at an estimate of the valgus correction.

-

What is the direction and degree of rotation of the limb as it is maximally adducted?

This movement of the limb as it is maximally adducted as well as the foot progression angle as the patient walks are important to note. If there is a normal foot progression angle but the limb externally rotates as it is adducted, the osteotomy (either proximal or distal) will need to compensate by rotation in the opposite direction and to the same degree. This maintains the foot progression angle. Similarly if there is a pre-existing rotational contracture as seen in an abnormal foot progression angle, the size of this deformity will need to be included in the calculation of the amount of derotation required. We emphasize the importance of noting the rotation of the limb in adduction in the coronal plane—as such it is preferable the contralateral limb is abducted away when this measurement is made clinically.

-

Is there a fixed flexion deformity and what is the arc of flexion/extension in the sagittal plane?

Similarly in the sagittal plane a useful correction of a fixed flexion deformity of the hip can be accomplished at the proximal osteotomy site. As in the coronal plane, the arc (of flexion and extension) is important. This is often limited and may be less than 90°. The extension osteotomy will reposition this arc in the sagittal plane and whilst full correction of the fixed flexion deformity may, at first sight, be desirable in order to reduce the exaggerated lumbar lordosis, this may induce a penalty of difficulty with putting on shoes in the sitting position if the maximum range of flexion of the hip is reduced. A balance is needed and this best discussed with patients and their parents.

-

Is the contralateral hip normal?

The pelvic support osteotomy serves to eliminate adduction (and so the Trendelenburg sign), reduce the fixed flexion contracture, equalise limb lengths and allow for a level (horizontal) pelvis when standing, with parallelism of the lower limbs. If the contralateral hip is abnormal, much of what is expected on the treated side can be offset by restricted movements or contractures on the opposite side. Careful consideration of the impact of abnormalities of the opposite side will need to be included in the preoperative deliberations.

Planning from X-ray assessment

This requires three radiographs: an anteroposterior view of both lower limbs with the patient standing (preferably a parallel beam scanogram [18]), an anteroposterior view of the pelvis with the affected hip in maximum abduction and subsequently fully adducted (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Three radiographs needed for the assessment and planning for a pelvic support osteotomy: a a standing full length view of both lower limbs; b AP view of the pelvis with leg in full abduction to reveal an adduction contracture if present; c AP view of the pelvis with leg in full adduction

The parallel beam scanogram (or equivalent X-ray) serves to document the presence of any deformities of the femur and tibia in the coronal plane in addition to the hip pathology. It provides an estimate of limb length inequality but any fixed flexion deformity of the hip should herald caution on the interpretation of these length measurements.

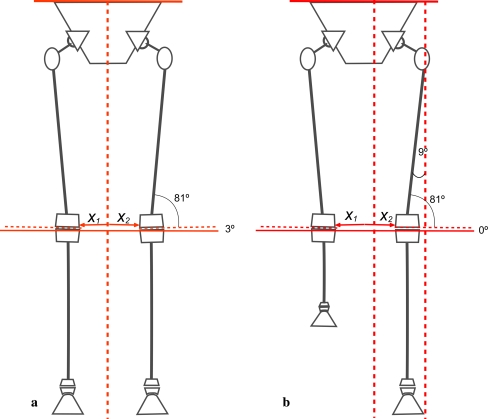

In standing (bipedal stance) the pelvis is level if both limbs are equal in length and contractures absent in any of the lower limb joints. With the feet at shoulder’s width, the knee joint subtends a slight valgus inclination to the horizontal (3°). Several changes occur in single stance of gait. The weight-bearing limb becomes slightly adducted to the vertical (about 3°); in so doing the knee joint inclination is horizontal and parallel to the ground (Fig. 4a) [19]. Bodyweight remains roughly in the midline and produces a moment that tends to drop the pelvis slightly on the unsupported side—this is countered by the action of the hip abductor muscles [20]. It is this position of the pelvis and of the weight-bearing limb in single stance that serves as a reference in planning for a pelvic support osteotomy. Therefore a horizontal lie to the pelvis with the knee and ankle joint inclinations parallel to it and to the ground are the reference positions. Through using the standard reference angles, the femoral shaft will be 9° to a vertical axis when the limb and pelvis are in this position (Fig. 4b).

Fig. 4.

Schematic representation of relationships between the pelvis, knee and femur in bipedal and single limb stance. a In bipedal stance with the feet at shoulder’s width, the knee joint is at slight valgus to the horizontal plane (3º). Both knees are equidistant to the midline vertical axis (x1 = x2). b In single stance, the knee and ankle joint of the weight-bearing limb are horizontal and parallel to the pelvic line. This is accomplished through a slight adduction at the hip. The femoral shaft subtends an angle of 9º to the midline vertical axis. The ground reaction force moves closer to the standing leg, x1 ≠ x2

The view of the pelvis with the hip maximally abducted allows a measurement of the adduction contracture, if present. The size of contracture needs to be added to the maximum amount of hip adduction to arrive at an estimate of the size valgus correction at the proximal osteotomy. The measurements can be made using the axis of the femoral shaft and a vertical axis of the pelvis (right angles to the horizontal axis) as references, noting that the neutral position of the femoral shaft is a varus inclination to the vertical axis of 9°. The size of the valgus correction at the proximal femoral osteotomy is therefore the sum of the adduction contracture and the amount of maximum adduction. Several authors have also recommended overcorrection at this osteotomy level, varying from 15° [14, 17, 21] to 25° [9]. The size of overcorrection is in anticipation of remodelling at the valgus osteotomy and some atrophy of the interposed soft tissue between femur and lateral wall of pelvis.

This method of calculating the size of valgus osteotomy is unlike previous descriptions. We have chosen not to use the single stance drop angle of the pelvis [22] as we find patients unable to balance well on the affected leg in single stance without use of additional support. This difficulty makes the method less reliable than that described above.

Translating the findings from clinical and X-ray planning

Proximal femoral osteotomy: level, degree and direction of osteotomy

Level of osteotomy

When the femoral shaft is fully adducted against the lateral wall of the pelvis, an AP X-ray of the pelvis gives a projection of abutment (as opposed to actual contact as we are dealing with two dimensions on X-ray) and this depicts the level of the proximal osteotomy. This level can vary depending on the resting position of the femur in relation to the pelvis: in undiagnosed hip dislocations, where there can be greater proximal migration of the femur, this may be located at a level coincident with the superior border of the obturator foramen; in other scenarios the level of proposed osteotomy lies coincident with part of the projection of the ischial tuberosity.

Amount of valgus

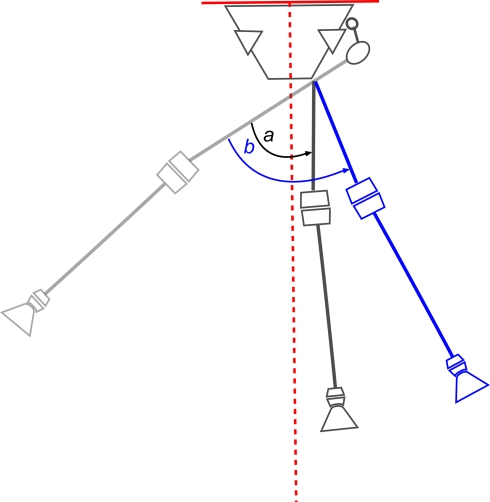

Slightly different recommendations have been made with regard to the amount of abduction performed at this osteotomy. Most authors have suggested an abduction angle that is either equal to the single stance pelvic drop angle or the measured range of adduction, plus an overcorrection factor of 15°–25°. We draw attention to two practical points in this regard: firstly it can be difficult to obtain a single stance pelvic drop angle without the patient requiring some form of additional support to achieve balance and, secondly, the measured range of adduction does not account for an adduction contracture that may commonly exist. We therefore recommend the angle of valgus correction to be estimated as the sum of the measured range of adduction plus the size of adduction contracture, if present. To this is added an amount of overcorrection. It is often quoted that an overcorrection offsets the loss of the valgus from remodelling at the osteotomy site. We would also like to point out that, irrespective of the size of overcorrection, much of this is cancelled if the second distal femoral osteotomy restores the position of knee joint inclination to parallel to the horizontal line of the pelvis. This can be explained as follows: any overcorrection at the proximal level leaves the patient with an ‘abduction contracture’, i.e. an inability to bring the leg parallel to the other in bipedal stance unless there is tilting of the pelvis (Fig. 5). If a varus correction is produced at the distal osteotomy, then the effect of this ‘abduction contracture’ is lost (and so will any overcorrection at the proximal osteotomy). Therefore maintaining a residual ‘abduction contracture’, which is what an overcorrection becomes, is a function of incomplete correction of the axis at the distal osteotomy. However we believe that an overcorrection factor should be added to the valgus correction at the proximal osteotomy because a failure to do so will leave the entire limb medialised and much closer to the midline than the contralateral side. In fact, an overcorrection of 9° will leave the shaft of the femur parallel to the vertical axis of the pelvis (Fig. 5). In view of this, we suggest that the overcorrection performed at the proximal osteotomy level should be greater than the 25° suggested by Choi et al. [9] to enable an abduction of the shaft of the femur away from the midline. An overcorrection of 30°–40° brings the post-osteotomy angle of Milch close to the recommended 240°.

Fig. 5.

Performing a valgus osteotomy equal in size to the maximum range of adduction plus any adduction contracture will bring the femoral shaft to its normal inclination of 9° to the vertical. Bringing the shaft to vertical therefore overcorrects by 9° (valgus correction a). This does not lateralise the shaft or knee joint sufficiently. Therefore an overcorrection in the region of 30° is preferable to allow a shift of the limb from the midline (valgus correction b). This overcorrection in effect produces an ‘abduction contracture’, i.e. in order to stand with both legs parallel, the patient has to tilt the pelvis

Amount of extension

The second component of the proximal femoral osteotomy is extension to overcome the effects of a fixed flexion contracture of the hip. A full correction of the fixed flexion deformity, without due consideration of the arc of hip flexion can be disadvantageous. If the arc is small, some consideration to the loss of maximum hip flexion is needed; whilst patients may benefit from a better standing posture (having reduced or eliminated their lumbar lordosis), they may complain from being unable to fasten on their shoes. Certainly a proportion of the fixed flexion contracture can be compensated for in the osteotomy and this usually amounts to 20°.

Amount of derotation

In the clinical assessment, some note of the torsional profile of the femur was made: both in terms of the foot progression angle when walking and the amount and direction of rotation when the femur was fully adducted against the lateral wall of the pelvis. The sum of the two clinical findings will need to be incorporated as a derotation osteotomy—this incorporation can be with either the proximal or distal femoral osteotomy.

Distal femoral osteotomy: level, degree and direction of osteotomy

Level of osteotomy

This second osteotomy is Ilizarov’s contribution to the pelvic support technique that addresses the excessive valgus of the proximal osteotomy and allows for derotation (if not done proximally) and lengthening as well (Fig. 6). Some authors have advocated the distal osteotomy be performed at the intersection of two lines: a vertical axis that is dropped from the horizontal line of the pelvis which traverses through the proximal osteotomy site and the mechanical axis of the tibia extrapolated proximally [14, 17, 22]. Using the method of the intersecting axes, the site of the distal osteotomy will vary depending on the amount of valgus overcorrection introduced; similarly, it will also vary if the position of the proximal osteotomy is in line with the medial edge of the ischial tuberosity as compared with its lateral edge. This imparts some variability to the final position of limb in reference to the midline of the body. If the osteotomy is performed too proximally it can medialise the entire limb and vice versa. Although a restoration of the mechanical axis is put forward as the reason to perform the second femoral osteotomy according to the intersection of axes above, it is assumed that the ‘centre of the joint’ of the new femoral—pelvic articulation is at the point of contact of the first osteotomy to the pelvis. We do not believe this to be true as, in the coronal plane, when the limb is abducted the axis of rotation lies further lateral to this point. Furthermore this axis of rotation is different in the sagittal plane and does not coincide with that in the coronal. This variation is a reflection that we no longer have a ‘joint’ in the normal meaning and a false articulation. With the standard definition of a mechanical axis, which is a line drawn from the centre of one joint to the centre of the next joint, we are unable to apply it in this setting satisfactorily.

Fig. 6.

The second osteotomy removes the ‘abduction contracture’ and allows both limbs to be parallel, with the knee, ankle and the pelvis horizontal. The treated side remains in maximum adduction at its articulation with the pelvis, and therefore prevents a Trendelenburg gait. Lengthening at the second osteotomy removes limb length inequality

We advocate the level of the distal osteotomy be placed such that after varus correction, the centre of the knee joint is the same distance from the midline of the body as compared with the contralateral side. This level can be determined using image manipulation software or using simple trigonometry (Fig. 7). In working out the level of the distal osteotomy, the following X-ray parameters are measured:

Distance of the centre of the contralateral knee to the midline axis of the body (from the standing AP film of both lower limbs)

Distance of the proposed proximal osteotomy site from the midline axis of the body (from the AP film of the pelvis with hip in maximum adduction)

Proposed overcorrection—we recommend adding 30° of extra valgus to the sum of the adduction range and measured adduction contracture. Nine degrees of this overcorrection will bring the femur parallel to the vertical axis, and the remaining 21° will take the femur away from the midline.

Fig. 7.

The level of the second osteotomy is to allow the limb to return to a near parallel alignment to the contralateral normal side but leave a small residual overcorrection of valgus. The position of this osteotomy can be worked out as part of the preoperative plan using the equation described in the text where y = (x1 − x2)/sine θ

The trigonometric solution to the level of the second osteotomy as measured along the femoral shaft distal to the first osteotomy is given by (Fig. 7):

|

|

where

- x1

distance to centre of knee from midline (on contralateral side)

- x2

distance to level of first osteotomy from midline

- y

distance along the shaft of the femur to second osteotomy

- θ

angle of overcorrection—9°

Amount of varus

It was described that, in single stance, the ankle and knee joint inclinations in the coronal plane should be horizontal and parallel to the pelvis. Therefore this osteotomy serves to bring the inclination of the knee joint parallel with that of the horizontal line of the pelvis. However doing this will effectively remove any degree of overcorrection that is intentioned in the surgical planning. To maintain some overcorrection, we suggest that the distal osteotomy is undercorrected (the knee joint line left in some valgus created by the proximal osteotomy); a convenient method is to leave the femoral shaft parallel to the vertical axis of the pelvis, thereby producing a valgus overcorrection of 9°–10°. This explains the trigonometric method above which aims to bring the femoral shaft parallel to the vertical midline axis, thereby leaving a valgus inclination at the knee of 9° which is equivalent to an ‘abduction contracture’ of the same amount.

Amount of derotation

This can be performed at the distal osteotomy instead of the proximal. The amount will depend of the findings of the clinical examination described earlier.

Amount of lengthening

The parallel beam scanogram provided an estimate of the length discrepancy between the limbs. The most reliable measure of this difference is performed after the pelvic support osteotomy is carried out. A new scanogram is needed and, together with a clinical estimate using blocks, the leg length discrepancy should be evaluated again. Lengthening is performed through the second osteotomy site in accordance with the principles laid down by Ilizarov. Over-lengthening is to be avoided as it is poorly tolerated in a hip that is already in full adduction.

Summary

Pelvic support osteotomies offer a significant improvement in posture, gait and walking tolerance to those adolescents and young adults who have hips destroyed by neonatal sepsis or through untreated congenital dislocations. The preoperative considerations involve a careful clinical and radiological assessment together with a discussion of alternative surgical solutions. Surgical planning is based on data obtained from clinical and X-ray assessment; both will provide the surgeon with answers to: (a) the level of the proximal osteotomy; (b) the amount of valgus, extension and derotation at the proximal osteotomy; (c) the level of the distal osteotomy, and (d) the amount of varus and lengthening at the distal osteotomy.

References

- 1.Lance PM. Osteotomies sous-trochanterienne dans le traitement des luxations congenitales inveterees de la hanche. Paris: Masson & Cie; 1936. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Milch H. The ‘pelvic support’ osteotomy. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1941;23(3):581–595. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lorenz A. Ueber die Behandlung der irreponiblen angeborenen Huftluxationen und der Schenkelhalspseudoarthrosen mittels Gabelung (Bifurkation des oberen Femurendes) Wien Klin Wchnschr. 1919;XXXII:997. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schanz A. Zur Behandlung der veralteten angeborenen Huftverrenkung. Munch Med Wchnschr. 1922;IXIX:930. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ilizarov GA, Samchukov ML. Reconstruction of the femur by the Ilizarov method in the treatment of arthrosis deformans of the hip joint. Ortop Travmatol Protez. 1988;6:10–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hunka L, et al. Classification and surgical management of the severe sequelae of septic hips in children. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1982;171:30–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schiltenwolf M, et al. Late results after subtrochanteric angulation osteotomy in young patients. J Pediatr Orthop B. 1996;5(4):259–267. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kocaoglu M, et al. The Ilizarov hip reconstruction osteotomy for hip dislocation: outcome after 4–7 years in 14 young patients. Acta Orthop Scand. 2002;73(4):432–438. doi: 10.1080/00016470216308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Choi IH, et al. Surgical treatment of the severe sequelae of infantile septic arthritis of the hip. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2005;434:102–109. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200505000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sponseller PD, McBeath AA, Perpich M. Hip arthrodesis in young patients. A long-term follow-up study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1984;66(6):853–859. doi: 10.2106/00004623-198466060-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Callaghan JJ, Brand RA, Pedersen DR. Hip arthrodesis. A long-term follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1985;67(9):1328–1335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.El-Mowafi H. Outcome of pelvic support osteotomy with the Ilizarov method in the treatment of the unstable hip joint. Acta Orthop Belg. 2005;71(6):686–691. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Paavilainen T, Hoikka V, Paavolainen P. Cementless total hip arthroplasty for congenitally dislocated or dysplastic hips. Technique for replacement with a straight femoral component. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1993;297:71–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Inan M, Bowen RJ. A pelvic support osteotomy and femoral lengthening with monolateral fixator. Clin Orthop. 2005;440:192–198. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000180602.00487.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aksoy MC, Musdal Y. Subtrochanteric valgus-extension osteotomy for neglected congenital dislocation of the hip in young adults. Acta Orthop Belg. 2000;66(2):181–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Berry DJ. Total hip arthroplasty in patients with proximal femoral deformity. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1999;369:262–272. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199912000-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rozbruch SR, et al. Ilizarov hip reconstruction for the late sequelae of infantile hip infection. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87(5):1007–1018. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.C.00713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saleh M, Milne A. Weight-bearing parallel-beam scanography for the measurement of leg length and joint alignment. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1994;76(1):156–157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Paley D. Normal lower limb alignment and joint orientation. In: Paley D, editor. Principles of deformity correction. Berlin: Springer; 2002. pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gage JR. Gait analysis in cerebral palsy, 1st edn. Clinics in developmental medicine, vol 121. London: Mac Keith Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Manzotti A, et al. Treatment of the late sequelae of septic arthritis of the hip. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2003;410:203–212. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000063782.32430.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Paley D. Hip joint considerations. In: Paley D, editor. Principles of deformity correction. Berlin: Springer; 2002. pp. 647–694. [Google Scholar]