Abstract

This study investigate the efficacy of pre-operative pain treatment for patients with hip fractures using fascia lliaca compartment block (FIB) technique performed by junior registrars (JR) as a supplement to conventional pain treatment. The FIB technique has routinely been used pre-operatively in the emergency department since 1 January 2004 for all patients with hip fractures. Over an 8-month period, 187 patients were treated. FIB was performed with 40 ml lidocaine and bubivacaine. A simple 5-step verbal pain score and maximal passive hip flexion was used as objective and subjective pain measurements. Effect of FIB was prospectively assessed on 70 patients: 2/3 females, mean age 80.7 (SD = 7.8), 36% in ASA-group III and IV (95% CI, 0.25–0.48). The median pain-free hip flexion pre-block was 15° (SD = 17) this improved to a median of 28° (SD = 21) 15 min post-block (P = 0.014) and 37° (SD = 26) 60 min post-block (P = 0.030). The median simple verbal pain score (0–4) pre-block was 2.2 (SD = 0.92). This decreased to a median of 1.5 (SD = 0.78) 15 min post-block (P < 0.001) and 1.3 (SD = 0.71) 60 min post-block (P = 0.021). No side-effects were observed. There was no correlation between the number of FIB previously performed by the attending registrar and the improved maximal hip flexion (ρ = 0.090, P = 0.50) or reduction in subjective pain score (ρ = 0.005, P = 0.971). FIB performed by JR is a feasible, efficient pre-operative supplement to conventional pain-treatment for patients with hip fractures. FIB is easy to perform, requires minimal introduction, no expensive equipment and is connected with a minimal risk approach.

Keywords: Fascia iliaca compartment block, Hip fracture, Pre-operative analgesia

Introduction

The incidence of hip fractures (HF) in Denmark is approximately 370 per 100.000 population per year equalling 14.000 HF a year. Apart from being a common fracture type, patients with HF occupy most beds in Danish hospitals [1] and are encumbered with high mortality. Patients with HF are generally characterized by advanced age and co-morbidity with epidemiological studies showing 30-day and 1-year mortality rates of 13.3 and 25%, respectively [2, 3]. Hip fractures are painful and appropriate pain relief is an important pre-operative objective. Conventional pain treatment (NSAIDs, paracetamol and IV morphine) has undesirable side-effects, many of those being particularly unwanted in HF patients with high co-morbidity. Morphine administration may cause respiratory depression, hypotension, dizziness, mental confusion, constipation, itching, urine retention and nausea. NSAIDs may cause gastrointestinal haemorrhagic and/or affect renal function. Fascia iliaca compartment block (FIB) is reported to effectively block nervi femoralis and nervi cutaneus femoris lateralis in 80–90% of patients when performed by specialists in anesthesiology or orthopedics (even without the use of a nerve-stimulator) and without causing major side effects [4–6]. However, these specialists are not always present in the emergency department of district hospitals and very often their attendance is substantially delayed due to other duties. The aim of the present study was to investigate the efficacy of FIB performed by junior registrars as a supplement to conventional pain treatment when a HF was suspected.

Methods and materials

The FIB technique (see below) is routinely used in the emergency department of Viborg District Hospital in Denmark since January 2004 for all patients with a clinical diagnosis of HF prior to transport to the X-ray department except in patients with a known bleeding diathesis, inguinal hernia or previous hypersensitivity to local anesthetics. The FIB is applied without using a nerve stimulator. Local analgesia is injected into the fascia iliaca compartment in the groin where nervi femoralis and nervi cutaneus femoris lateralis are located [7]. The duration of FIB is 8–10 h. If a delay to surgery exceeded the duration of the FIB, it was repeated or conventional analgesia prescribed (tablets or IV morphine).

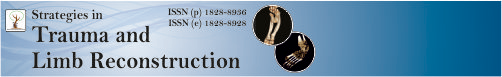

The procedure and technique of the FIB is described by Dalens et al. [6]. A line is drawn on the skin from pecten ossis pubis to spina iliaca anterior superior and divided in three equal parts. The puncture site is marked, 1–3 cm distal to the point where the middle and lateral third of this line meet. Arteria femoralis is identified medial to the intended puncture site (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Puncture site

Puncture site

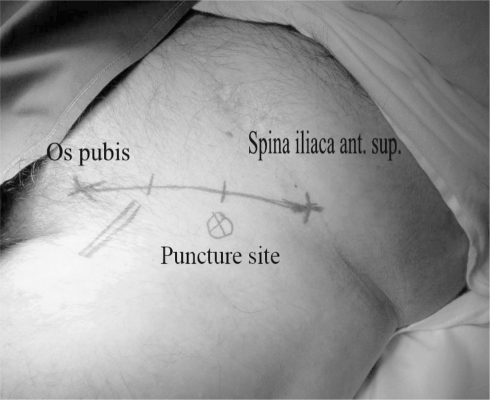

Identification of the correct compartment is based on two ‘gives’ followed by a loss of resistance; first ‘give’ felt is fascia lata and second is fascia iliaca. We use an “obtuse” needle (45° cut) to make it easier to feel the ‘give’ (see Fig. 2). The block is performed with 30 ml bupivacaine (2.5 mg/ml) and 10 ml lidocaine (2%). In patients weighing less than 50 kg the quantity is reduced by half.

Fig. 2.

Anatomy of fascia iliaca compartment. 1 fascia lata, 2 fascia iliaca, 3 N. femoralis, 4 N. cutaneus femoris lateralis, 5 V. og A. femoralis, 6 M. pectinale, 7 M. psoas

Anatomy of fascia iliaca compartment

During an 8 month period 187 patients were treated for hip fractures. Subjective and objective data on the effectiveness of the FIB were prospectively collected for 70 patients. Not all cases with the diagnosis of hip fracture were enrolled owing to the high levels of activity within the emergency department and the time constraints this activity produced. The 70 patients enrolled were comparable with the overall group with respect to age, gender, fracture type and ASA-classification.

Eighteen different junior registrars performed the block (previous numbers of FIB per junior registrar varied between none to more than 30). Patient characteristics were recorded (gender, age, weight, height, medication, type of fracture, ASA-classification, a new mobility score as described by Parker and the Hindsøe score). Fractures were classified as either intra-capsular or extra-capsular. The new mobility score (scale 0–9) described the patient’s mobility before fracture. The rehabilitation potential was considered satisfactory if the accumulated score was equal to or greater than five [8]. The Hindsøe score (scale 0–9) was used to assess cognition by screening the memory faculties of the patient (see Table 1). A score equal to or less than six was considered as indicative of impaired cognitive function [9].

Table 1.

Hindsøe score

| Mental score (every negative answer gives one point) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Can account for age | Yes | No |

| Can account for social security number | Yes | No |

| Can account for home address | Yes | No |

| Can account for phone number | Yes | No |

| Can account for own weight and height | Yes | No |

| Can account for date for hospitalisation | Yes | No |

| Can account for resound for hospitalisation | Yes | No |

| Can account for own medication | Yes | No |

| Can identify the interviewer after approximately 30 min | Yes | No |

| Total score (sum) | ||

Score 9–7: unaffected

Score 6–5: impaired cognitive function

Score 4–0: severe dementia

Hindsøe score

The effect of fascia iliaca block was assessed by subjective and objective means before and after applying the block. Subjective evaluation was measured through a semi-quantitative five-step simple verbal pain score (0 = no pain, 1 = mild pain, 2 = moderate pain, 3 = intense pain, 4 = worst imaginable pain). Objective changes were recorded from the range of comfortable passive hip flexion. Records were made immediately before the block was performed and 15 and 60 min thereafter. The number of previous FIB performed by the junior registrar was noted in each case. The amount of prescribed analgesia used before and after the block was also noted and the staff was instructed not to give morphine within 60 min after the block being introduced.

Statistics: non-parametric analysis was used. Wilcoxon’s signed rank sum test for paired data, Kruskal–Wallis test for non-paired data and Spearman’s correlation analysis for association between continuous variables. SPSS 10.0 statistics software was used. Differences were considered statistically significant at P < 0.05.

Patient characteristics

Seventy patients were enrolled over an 8-month period. Baseline characteristics of the patients are presented in Table 1. The mean age was 80.7 years (SD = 7.8). Two-thirds were female. The mean BMI was 23.15 (SD = 3.7); 22% had a BMI below 20 and 0% had a BMI above 35. The mean ASA grade was 2.27 (SD = 2.9), with 36% in group III and IV. The mobility score was less than five for 28% whereas 19% had a Hindsøe score of less than six. The distribution of intra- and extracapsular fractures was 46 and 54% respectively.

Subjective and objective pain measurements

Table 2 summarizes subjective and objective pain assessment before and after administering the fascia iliaca block. Pain was reduced markedly after administering the block as assessed both subjectively by the patient and objectively by the physician.

Table 2.

Patient characteristics (n = 70)

| Female | 67% | (95% CI, 0.55–0.78) |

| Mean age | 80.7 | (SD:7.8) |

| BMI <20 | 22% | (95% CI, 0.13–0.32) |

| BMI >35 | 0% | |

| New mobility score <5 | 28% | (95% CI, 0.18–0.41) |

| Hindsøe score <6 | 19% | (95% CI, 0.10–0.30) |

| ASA group III and IV | 36% | (95% CI, 0.25–0.48) |

| Intracapsular fractures | 46% | (95% CI, 0.34–0.58) |

| Extracapsular fractures | 54% | (95% CI, 0.42–0.66) |

| >5 kinds of medicine | 47% | (95% CI, 0.35–0.59) |

| Heart medication | 79% | (95% CI, 0.67–0.87) |

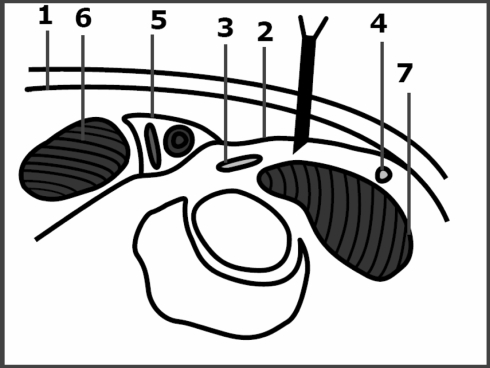

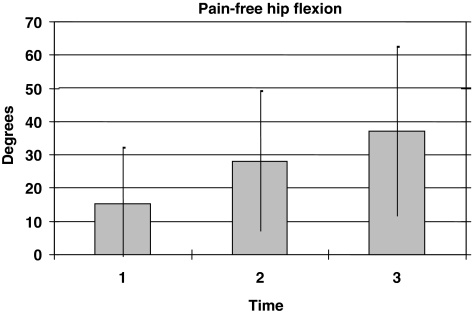

The median pre-block verbal pain score (0–4) was 2.2 (SD = 0.92), decreasing to a median of 1.5 (SD = 0.78) 15 min post-block (P < 0.001) and 1.3 (SD = 0.71) 60 min after the injection (P = 0.021, Fig. 3). Similarly the median pain-free hip flexion pre-block was 15° (SD = 17), improving to a mean of 28° (SD = 21) 15 min post-block (P = 0.014, Fig. 3) and 37° (SD = 26) 60 min after the injection (P = 0.030, Fig. 4). There was no significant difference in objective or subjective pain evaluation before the block when comparing patients with normal and impaired cognition (as assessed by the Hindsøe score).

Fig. 3.

Simple 5-step subjective verbal pain score before and after fascia iliaca compartment block application. 1, before block; 2, 15 min after block; 3, 60 min after block

Fig. 4.

Maximal pain-free hip flexion before and after fascia iliaca compartment block application. 1, before block; 2, 15 min after block; 3, 60 min after block

Correlation between improved maximal hip flexion after fascia iliaca compartment block (FIB) application and the number of FIB previously performed by the treating doctors

The administration of morphine prior to the FIB did not alter the efficacy of block. There was no correlation between the number of blocks previously performed by the attending registrar and the observed effect as evaluated by maximal hip flexion (ρ = 0.090, P = 0.50) and subjective pain score (ρ = 0.005, P = 0.971) (see Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Correlation between improved maximal hip flexion after fascia iliaca compartment block (FIB) application and the number of FIB previously performed. Scale for numbers of FIB previously performed by the treating doctors. 0, 0; 1, 1–4; 2, 5–9; 3, ≥10

Maximal pain-free hip flexion before and after FIB application

We used passive hip-flexion as a measurement for effectiveness of FIB. An increase in flexion of 10° or more was considered to be a sign of considerable pain relief. Using this threshold the block was shown to substantially relieve pain in 69.5% of cases (95% CI, 0.56–0.81).

No complication from the FIB was reported during the inclusion period. However review of case records for all 187 patients treated with the FIB during the study revealed that two patients transiently exhibited mild CNS symptoms thought to arise from bupivacaine intoxication. The patients did not suffer cardiovascular symptoms and both patients recovered within 1 h.

Discussion

An assessment of FIB as performed by junior registrars (and not specialists) has not been previously reported. This study demonstrates that FIB performed by junior medical doctors is a feasible and efficient supplement to systemic analgesia for patients with hip fractures.

After the introduction of FIB in 2004 in the emergency department of Viborg Hospital, the clinical observations and responses from all departments having pre-operative contact with patients with hip fractures have been positive. Patients have been easier to nurse and handle for pre-operatively procedures.

The FIB was first described in 1989 and performed earliest on children and later on adults. It was mainly used for post-operative pain relief (hip, femur and knee) but also in treatment of burns on the thigh or in pre-hospital treatment of femur fractures [13, 14]. In those studies patients with impaired cognitive functions were excluded. Furthermore all FIBs were performed by specialists. In this study 20% of included patients had impaired cognitive function as a comorbidity to the fracture. This proportion is comparable to other studies [1].

The limitations of this study include a selection bias that may have occurred through assessing the effect of the block in 70 out of 187 patients. However, no differences in age, gender, fracture types, ASA group, mobility and Hindsøe scores were noticed between enrolled and non-enrolled patients. In the statistical analysis the individual patient was his/her own control in recording pain before and after the FIB. Acute pain in the pre-operative phase and the inclusion of patients with impaired cognitive function creates practical difficulties for measuring the effectiveness of FIB in a traditional way using sensory and motor function assessments [12]. In an attempt to reduce information bias, we adopted a threshold of 10° of painless flexion as a measure of the effectiveness of the FIB.

Some previous studies have also attempted to evaluate the usefulness of the fascia iliaca block. In addition to a VAS score (visual analogue scale), Candal-Couto et al used passive hip-flexion and a ‘sitting-score’ as an objective measurement of FIB [10]. This made it possible to minimize information bias when including patients with impaired cognitive functions [5]. A simple verbal pain score was also used as a subjective pain measure. This score was used instead of the VAS score as patients with impaired cognitive function often are unable to understand the VAS scale.

The amount of conventional pain treatment used before and after the FIB was recorded. The staff was also instructed not to give morphine for the first 60 min after the FIB in order to prevent information bias and confounding.

The FIB technique is performed with minimal risk as the analgesic is injected at a safe distance from the arteria femoralis and the nervi femoralis [4–6]. It is important that the patient is able to respond during administration of the block as post-operative neuropathy has been observed with the FIB was performed on a patient in spinal anesthesia [11]. The FIB is safe if administered with repeated aspiration to ensure the local anesthetic is not injected directly into a blood vessel, the patient observed for a pain reaction to ensure analgesic is not injected directly into a nerve and close measurements of blood pressure and pulse are carried out after the procedure [3–5]. In addition to high safety profile of the FIB, it has also been shown to be an effective pain treatment [4–6].

This study showed no correlation between the recorded changes of passive hip flexion and the number of FIBs performed by the individual junior registrar. This observation suggests that the learning curve is relatively easy and that all junior registrars attached to the emergency department can perform the FIB after a short introduction. This feature of the FIB makes it a very practical and useful procedure in the emergency department as specialists seldom are available at all times in the emergency department of a district Hospital or their attendance may be delayed substantially due to other duties. It is possible to administer satisfactory pre-operative analgesia on patients with hip fractures earlier and safely by using the FIB. It is hoped, through this change of practice, the amount of conventional pain treatment (morphine and NSAID) and their attendant side effects can be reduced for this vulnerable group of patients (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Results—subjective and objective pain measurements

| N | Median | Standard deviation | Min. | Max. | Percentiles | P value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25th | 50th (median) | 75th | |||||||

| Subj. verbal pain-score | |||||||||

| Pre-block | 69 | 2.16 | 0.92 | 0 | 4 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 3.00 | |

| 15 min post FIB | 68 | 1.51 | 0.78 | 0 | 3 | 1.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 | P < 0,001 |

| 60 min post FIB | 63 | 1.32 | 0.71 | 0 | 3 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 2.00 | P = 0,021 |

| Obj. passive hip flexion | |||||||||

| Pre-block | 70 | 15.10 | 16.99 | 0 | 60 | 0.00 | 10.00 | 26.25 | |

| 15 min post FIB | 65 | 27.94 | 21.42 | 0 | 75 | 10.00 | 30.00 | 45.00 | P = 0,014 |

Conclusion

The fascia iliaca block is easy to perform and requires minimal introduction. There is no need for expensive equipment and is carried out with a low risk approach. This study has shown that the FIB performed by junior registrars is a feasible and efficient supplement to conventional pain treatment for patients with hip fractures before surgery. The efficacy of the block did not have a correlation to the number previously performed by the treating junior registrar and suggests the learning curve is relatively easy.

Conflict of interest statement

None.

References

- 1.Danish Orthopaedic Society; reference program concerning hip fracture—2006

- 2.Foss NB, Kehlet H. Mortality analysis in hip fracture patients: implications for design of future outcome trials. Br J Anaesth. 2005;94(1):24–29. doi: 10.1093/bja/aei010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heikkinen T, Parker M, Jalovaara P. Hip fractures in Finland and Great Britain—a comparison of patient characteristics and outcomes. Int Orthop. 2001;25(6):349–354. doi: 10.1007/s002640100272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morau D, Lopez S, Biboulet P, Bernard N, Amar J, Capdevila X. Comparison of continuous 3-in-1 and fascia iliaca compartment blocks for postoperative analgesia: feasibility, catheter migration, distribution of sensory block, and analgesic efficacy. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2003;28(4):309–314. doi: 10.1016/S1098-7339(03)00183-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Capdevila X, Biboulet P, Bouregba M, Barthelet Y, Rubenovitch J, d’Athis F. Comparison of the three-in-one and fascia iliaca compartment blocks in adults: clinical and radiographic analysis. Anesth Analg. 1998;86(5):1039–1044. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199805000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dalens B, Vanneuville G, Tanguy A. Comparison of the fascia iliaca compartment block with the 3-in-1 block in children. Anesth Analg. 1989;69(6):705–713. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zibigniew Koscielniak-Nielsen. perifere nerveblokader ved hjælp af elektronisk nervestimulation. 2006

- 8.Parker MJ, Palmer CR. A new mobility score for predicting mortality after hip fracture. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1993;75(5):797–798. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.75B5.8376443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hindsø K (1998) Prevention of hip fractures using external hip protectors. Risk factors for falls, hip fractures, and mortality; and evaluation of the consequences of fear of falling among older orthopaedic patients.A clinical, controlled, open intervention study including 1,684 patients, older than 74 years of age, followed for 1–2.5 years after admittance to one of two university hospitals in Copenhagen. Ph.d. Thesis, University of Copenhagen (Cited 2008 Feb 6). http//www.dadlnet.dk/dmb/dmb_phd/doc/Prevention_of_hip_fractures_Klaus_ Hindso.pdf

- 10.Candal-Couto JJ, McVie JL, Haslam N, Innes AR, Rushmer J. Pre-operative analgesia for patients with femoral neck fractures using a modified fascia iliaca block technique. Injury. 2005;36(4):505–510. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2004.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gros T, Bassoul B, Dareau S, Delire V, Roche B, Eledjam JJ. Postoperative neuropathy following fascia iliaca compartment blockade. Ann Fr Anesth Reanim. 2006;25(2):216–217. doi: 10.1016/j.annfar.2005.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jensen MP, Chen C, Brugger AM. Postsurgical pain outcome assessment. Pain. 2002;99(1–2):101–109. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(02)00063-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cuignet O, Mbuyamba J, Pirson J. The long-term analgesic efficacy of a single-shot fascia iliaca compartment block in burn patients undergoing skin-grafting procedures. J Burn Care Rehabil. 2005;26(5):409–415. doi: 10.1097/01.bcr.0000176885.63719.7e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lopez S, Gros T, Bernard N, Plasse C, Capdevila X. Fascia iliaca compartment block for femoral bone fractures in prehospital care. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2003;28(3):203–207. doi: 10.1053/rapm.2003.50134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]