Abstract

The distal ulna represents the fixed point around which the radius and the hand acts in daily living. The significance of distal ulnar fractures is often not appreciated and often results in inadequate treatment in comparison to its larger counterpart; the radius. There is little guidance in the current literature as how to manage these fractures and their associated injuries. This paper aims to critically review the current literature and combine it with treatment suggestions based on the experience of the authors to help guide investigation and management of these often complex injuries.

Keywords: Ulnar fractures, Adult, Injuries, Fracture fixation

Introduction

The distal ulna represents the fixed point around which the radius and the hand acts in daily living. The significance of distal ulnar fractures is often not appreciated and often results in inadequate treatment in comparison to its larger counterpart; the radius. There is little guidance in the current literature as how to manage these fractures and their associated injuries. This paper aims to critically review the current literature and combine it with treatment suggestions based on the experience of the authors to help guide investigation and management of these often complex injuries.

Background

We searched The Cochrane Library up to February 2008 and did not find any specific reviews regarding distal ulnar fractures. We also searched Dialog Datastar: Medline, Embase, AMED, Pubmed, Trip Database and Sumsearch. We found no articles regarding the treatment of distal ulnar fractures that had randomization or control groups (Table 1). All articles with reference to distal ulnar fractures and all abstracts were read by the first author. Any articles involving fractures in children were excluded. Papers in languages other than English were excluded. This left us with 20 non-anatomical articles and 6 case reports to analyze for the review (Table 1).

Table 1.

Types of clinical articles on distal ulnar fractures referenced in this review

| All distal ulnar fractures | Papers (n) | Patients (n) |

|---|---|---|

| Randomized or controlled trials | 0 | 0 |

| Prospective studies | 5a | 579a |

| Retrospective studies | 15 | 2,428 |

| Case reports | 6 | 8 |

| Ulnar styloid fractures | ||

| Prospective | 5a | 579a |

| Retrospective | 11 | 2,374 |

| Case reports | 2 | 3 |

| Simple ulnar head fractures | ||

| Retrospective | 1 | 3 |

| Case reports | 3 | 4 |

| Ulnar neck or distal shaft fractures | ||

| Retrospective | 3 | 36 |

| Comminuted ulnar head fractures | ||

| Retrospective | 1 | 15 |

| Case reports | 1 | 1 |

aAll prospective studies have dealt with ulnar styloid problems

Combined distal radius and distal ulna fractures

Most distal ulna fractures occur with a distal radius fracture. On the whole the clinical outcome following such an injury will be determined by the type and severity of the distal radius fracture. Consideration of the treatment of the distal ulna fracture should be given after the fracture to the radius has been dealt with. As a general rule if a radius fracture has been managed in such a way to allow early mobilisation then an attempt should be made to manage the distal ulna fracture in such a way as to allow early mobilisation. In the majority of cases the distal ulna can be treated as if it were in isolation once the management of the radial fracture has been completed/considered.

Acute ulnar styloid fractures

Anatomy

The management of acute ulnar styloid fractures is based on the long-term effect that they may have on the stability of the distal radioulnar (DRU) joint. The relationship of the ulnar styloid to the stabilizing ligaments determines whether a specific fracture type is likely to result in DRU joint instability.

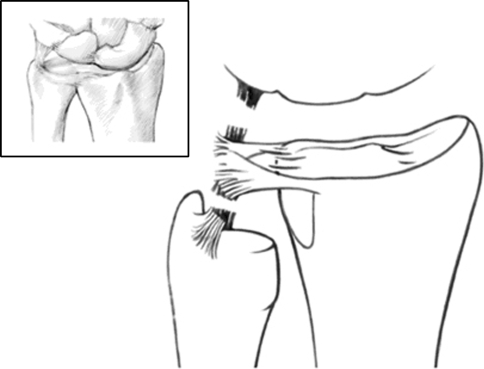

The static stability of the DRU-joint is achieved by the bony congruity between the sigmoid notch of the radius and the ulnar head and the ligaments which hold the joint together [1–3] (Fig. 1). The ulno-radial ligament represents the transverse, peripheral part of the Triangular Fibro-Cartilage Complex (TFCC) [1–8]. The ligaments run from the fovea of the ulnar head and the base of the ulnar styloid to the dorsal and palmar edges of the sigmoid notch on the distal radius [4–7, 9] (Fig. 1). The ulno-radial ligament is the major stabiliser of DRU-joint in the dorso/palmar direction [6, 10].

Fig. 1.

The relationship of the TFCC to the ulnar carpal ligaments

Accepted understandings

We found 5 prospective and 11 retrospective articles as well as two case reports that dealt with ulnar styloid fractures (Table 1). Ulnar styloid fractures seldom occur alone. More than 40% (range 21–61%) of distal radius fractures have an associated ulnar styloid fracture [11–17] (This increases to 86% if the radial fracture is intra-articular [18]). If the ulnar styloid fracture is associated with a distal radius fracture, the ulnar styloid fracture will reduce with reduction of the distal radius in many cases [19] (Fig. 2). In such circumstances they can be treated with an above elbow cast for 6 weeks [20]. Obviously, exact restoration of the radius fracture around the sigmoid notch is of paramount importance for DRU-joint stability [21]. In a retrospective study of 71 ulnar styloid fractures in 130 patients with distal radial fractures, the wrists had significantly greater instability of the DRU-joint if the ulnar styloid fracture was >2 mm displaced initially [11] (Fig. 3). This was even more obvious if the fracture was at the base of the ulnar styloid [11] as there was likely to have been an associated detachment of the ulno-radial ligament (Fig. 1). This is important as 41% of all ulnar styloid fractures occur at its base [11] and contribute to a poorer outcome because of their effect on DRU-joint instability [22]. Fixation of ulnar styloid base fractures with a single wire has been shown to restore DRU-joint stability in a small case series (n = 6) [10]. Fractures through the tip of the styloid are likely to be stable [20] (Fig. 4) and do not require fixation as the ulno-radial ligament remains attached to the ulnar head at the base of the styloid.

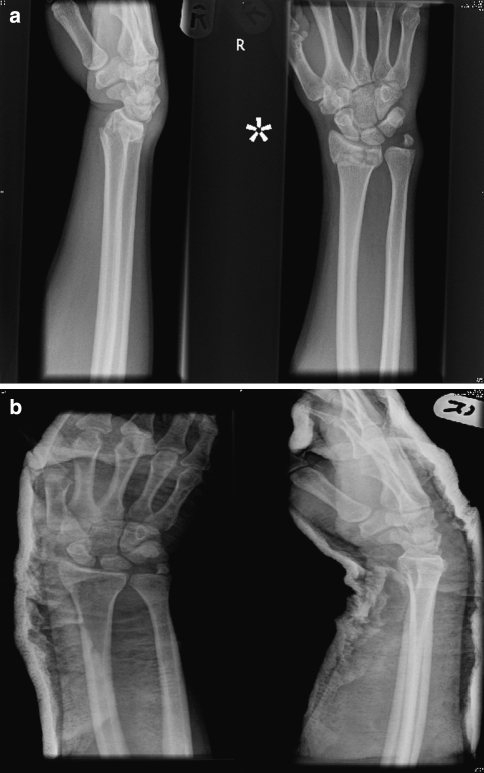

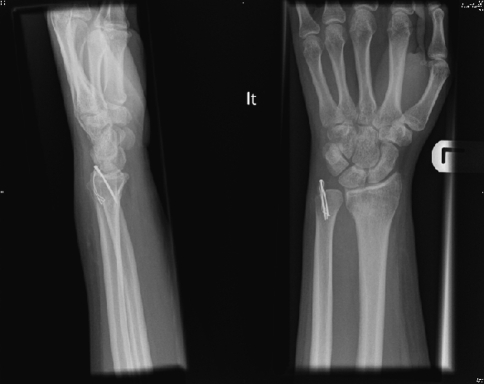

Fig. 2.

A 2-mm displaced ulnar styloid fracture that is reduced with reduction if the distal radius

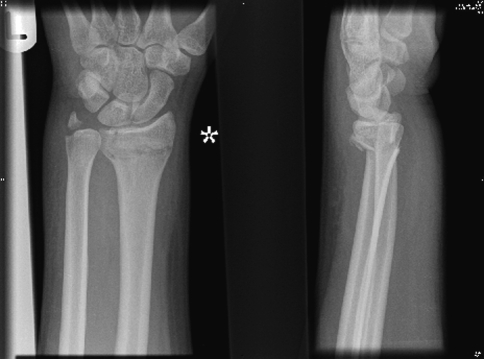

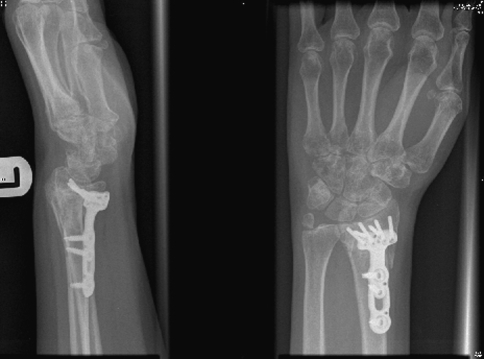

Fig. 3.

An ulnar styloid base fracture with more than 2-mm initial displacement

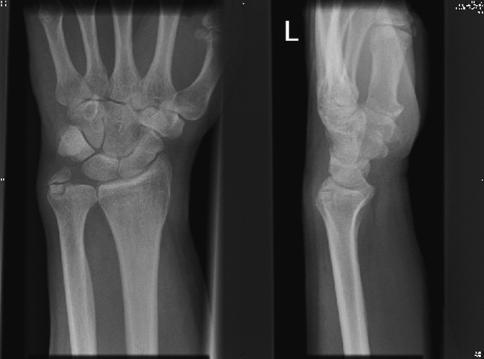

Fig. 4.

A fracture of the tip of the ulnar styloid with a stable DRU joint

Controversies

There is contradictory information regarding the importance of ulnar styloid fractures. Some claim that distal radial fractures with an associated ulnar styloid fracture have been shown to have an increased DRU-joint instability than distal radius fractures without an ulnar styloid fracture [11]. Others have found no difference when comparing the overall functional results with or without an ulnar styloid fracture [23, 24]. There are two possible reasons for this: 1. The ulnar styloid fracture may be distal to the true stabilising insertion at the fovea and does not affect the stabilizing properties of the ulno-radial ligament. 2. It is possible to have a destabilizing tear of the ulno-radial ligament in the absence of ulnar styloid fractures [25]. This may explain why late instability has been found without ulnar styloid fractures or non-unions [26]. To complicate matters further Triangular Fibro-Cartilage complex (TFCC) injuries have been found when there is no ulnar styloid fracture [12, 25] and these do not necessarily translate to instability of the DRU-joint.

Treatment of acute ulnar styloid fractures

We emphasize that ulnar styloid fractures have to be assessed not solely as a bony fracture, but as a possible destabilizing injury to the ulno-radial ligament. Based on the published literature to date acute ulnar styloid fractures can be managed in the following ways.

-

Ulnar styloid fracture irrespective of DRU joint instability

Ulnar styloid fractures at its base with initial displacement more than 2 mm should be treated with open reduction and internal fixation [11, 20]. In our view the decision to fix the ulnar styloid is increasingly justified if the ulnar styloid is displaced in a radial direction (detaching the ulno-radial ligament) than in axial, distal direction (detaching the ulno-triquetral collateral ligament). The fixation can be done with a single K-wire [10, 22], tension band wiring [20] (Fig. 5), a wire loop/suture [22] or screw fixation [27].

-

Instability of the DRU joint irrespective of the ulnar styloid fracture

Whether or not there is an associated distal radial fracture, it is important to assess DRU-joint stability in order to decide whether the styloid needs reattaching or not [10, 19, 20]. If the DRU-joint is unstable then either re-attach the ulnar styloid (which has the ulno-radial ligament attached to it) or the ligament alone. Direct repair or reattachment of the ulno-radial ligament to the fovea of the ulnar head is required if the ulnar styloid fragment is too small or if DRU-joint instability is present without an ulnar fracture.

-

Immobilisation without fixation

If the ulnar styloid fracture is undisplaced or reduces with reduction of the distal radius, as happens in most cases [19], patients can be treated with an above elbow cast for 6 weeks [20].

Fig. 5.

Tension band wire fixation of an ulnar styloid fracture

Symptomatic ulnar styloid fracture nonunion

Accepted understandings

The incidence of ulnar styloid fracture nonunion is between 26% [15] and 63% [14]. Of these only around 14% of patients have ulnar sided wrist pain [17]. There are a number of reasons why a non-united ulnar styloid fracture can become symptomatic: It can be responsible for a non-functioning ulno-radial ligament (peripheral TFCC detachment) [27] (Fig. 6), cause impingement of the overlying ECU tendon [28], abut on the carpus [27, 29] (Fig. 7) or be an irritative loose body [27] (Fig. 8). A constant physical finding in these patients is an ulnar sided wrist pain worse with wrist use and loading in rotation, combined with tenderness over the ulnar styloid [27]. Patients with ulnar styloid fractures at the base that malunite in a displaced position or go on to nonunion may develop DRU-joint instability. Tsukazaki et al. [30] identified that most patients with DRU-joint instability had a nonunion of an ulnar styloid fracture (13 out of 17).

Fig. 6.

Unstable DRU joint after an ulnar styloid base fracture nonunion

Fig. 7.

Abutment of ulnar styloid nonunion on the carpus

Fig. 8.

Ulnar styloid nonunion acting as an irritative loose body

Controversies

Functional outcome scores for patients with nonunion of an ulnar styloid fracture are no worse than those that have united [14]. It has also been found that ulnar styloid nonunion is not associated with DRU-joint instability [25]. This is most likely explained by the fact that the nonunions have not been assessed to represent a destabilizing ligament injury but only a bony nonunion. Given the anatomy there ought to be a difference between a nonunion at the base as opposed to a more distal nonunion. However, we have not found any scientific support for this assumption in the articles we have reviewed.

Treatment of symptomatic ulnar styloid nonunions

Treatment of an ulnar styloid nonunion should be considered if patients are symptomatic and/or have DRU-joint instability [27]. The ulnar styloid nonunion should be treated as a bony nonunion and be reattached to the ulnar head if the fragment is large [27], [28] (Fig. 9). If the fragment is small, it should be shelled out and the ulno-radial ligament should be reattached directly to the fovea of the ulnar head [27]. Patients treated in this way have been reported to have good to excellent results [27, 28]. If there is no DRU-joint instability the ulnar styloid can be shelled out without any associated ligament procedure [21, 27, 31]. This can relieve localised pain without causing instability [31]. It is then important to re-test the stability of the DRU-joint.

Fig. 9.

Reattachment of a large ulnar styloid fracture nonunion with associated DRU joint instability

Ulnar head fractures (2 part)

Accepted understandings

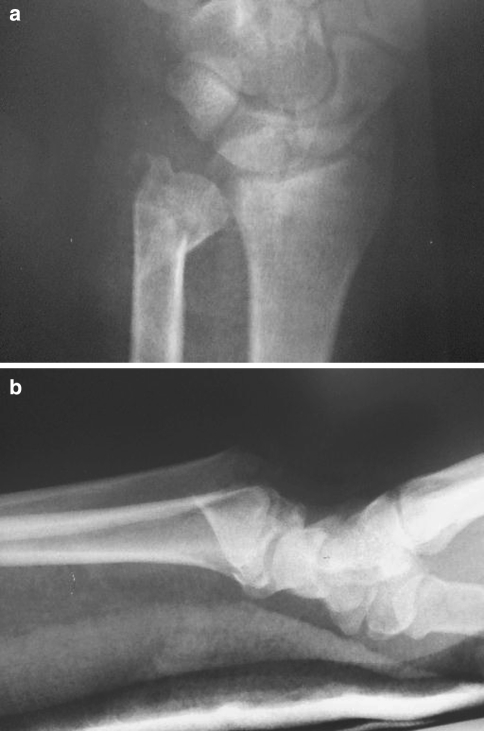

There are only some case reports in the literature [32–35] to scientifically advice us what to do with ulnar head fractures (Table 1). Intra articular fractures of the ulnar head are often associated with fractures of the radius. They can also occur in isolation [32–34]. For treatment purposes they can be classed as two types. 1. Head fracture alone, or 2. Head fracture with involvement of extra-articular parts of the distal ulna (including the styloid) (Fig. 10).

Fig. 10.

Ulnar head fracture

Head fracture alone

Fractures that are displaced with an intra articular step or that are unstable are treated with open reduction and internal fixation with buried headless compression screws [32, 34] or Kirschner wires [33] or with internal locked plates [35]. Immobilisation after fixation depends on the stability of the fracture and its fixation. Excellent results have been reported in the sparse literature using these methods [32–35].

Head fracture with extra articular component

There are only three reported cases of ulnar head fractures with an extra-articular component found in our search [33, 35]. In one case the articular component was treated with a buried headless compression screw and the ulnar styloid fracture with tension band wires [33]. Two cases were treated with an internal locked plate [35]. Post-operative immobilisation was similar to fractures of the head alone and an excellent result was achieved in these cases.

Controversies

The literature on ulnar head fractures is sparse with only case reports for review [32–35] (Table 1). As they are most often associated with distal radius fractures the pattern of the distal radius fracture will have a strong influence on the overall functional outcome [30]. If the radius fracture is intra-articular involving the DRU-joint the functional outcome may already be determined irrespective of the treatment of the ulnar head fracture. However, a stable anatomical fixation of the ulnar head fracture along with stable fixation of the distal radius (if associated) may allow earlier movement and achieve an overall improvement in the functional outcome.

Treatment of ulnar head fractures

We cannot recommend operative fixation in all cases based on the current literature. It will, however, depend on the fracture pattern, displacement and stability and whether the physician can or would like to mobilise the patient early. We do recommend a Computer Tomography (CT) scan of the fracture to assess fragment sizes, displacement and suitability for primary fixation.

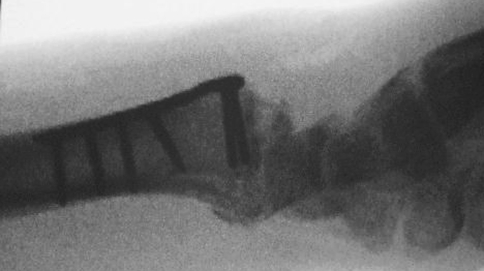

In general, the method of fixation would depend on the fracture pattern. An intra articular fracture is best treated with a buried headless screw. If the extra-articular component extends towards the neck of the distal ulna a fixed angle device such as a condylar blade plate (Fig. 11) or an internal locking plate [35] is recommended. Tension band wiring is recommended if the extra articular component involves the ulnar styloid.

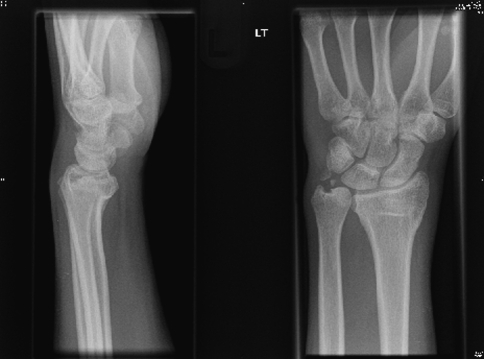

Fig. 11.

Blade plate fixation of intra-articular ulnar head fracture extending into the ulnar neck with other extra articular fragments

Distal ulnar neck or distal shaft fractures

We define distal ulnar neck or distal shaft fractures to be those that occur within 5 cm of the distal dome of the ulnar head.

Accepted understandings

Not many scientific conclusions can be made from the few reports that deal with distal ulnar neck of shaft fractures (Table 1). Many of the patients with distal ulnar fractures in association with distal radial fractures realign and are considered to be stable once the radius is reduced [36]. Displaced or comminuted distal ulnar neck or shaft fractures can disrupt the DRU-joint [37] and thus may affect the functional outcome with regards to movement and pain in this joint.

Controversies

In our experience, most distal neck or shaft fractures are associated with a distal radius fracture unless there is a direct injury to the ulna. The ulnar fractures that do not reduce when the distal radius is reduced often tend to be very distal. It is therefore difficult to improve reduction by closed means. It is also difficult to immobilise unstable fractures with cast treatment alone as it is very difficult to effect a three point fixation, even in an above elbow cast.

Treatment of distal neck or distal shaft fractures

Isolated stable fractures, caused by a direct injury, or those that are stable once the radius has been reduced can then be treated with immobilisation in an above elbow cast [36]. Irreducible or unstable fractures require open reduction and internal fixation [36, 37]. This can be achieved using either a blade plate [36], tension band wiring supplemented by intra-fragmentary screws [37] or an internal locking plate [25]. These methods have been shown to be successful in a small number of retrospective case series.

Comminuted intra-articular distal ulnar fractures

Accepted understandings

Comminuted distal ulnar fractures have only been mentioned in the literature in a case report (n = 1) [38] and a retrospective study on 15 patients [39] (Table 1). Such a fracture is likely to give a poor outcome. In the case report a primary ulnar head prosthesis was used [38]. Postoperatively movement was started early and an excellent final range of movement was achieved [38]. Seitz and Raikin reviewed 15 consecutive distal radius fractures with comminuted head fragments where the ulna had been managed with head resection and soft tissue interposition [39]. At an average of 5.8 years follow up patients had gained 85% of wrist movement and 88.6% of average grip strength compared with the contralateral wrist.

Controversies

The interpretation of outcome will always be difficult as the vast majority will have an associated complex distal radius fracture. With regard to the comminuted distal ulnar fracture the surgeon has two possible options.

The first option is to restore and maintain the overall alignment of the ulna and DRU-joint. This could be done with manipulation and above elbow cast immobilisation alone or alternatively by surgical means with temporary wiring or external fixation. A salvage procedure could then be considered at a later date depending on the outcome. The potential problems with this management are wrist stiffness and reduced forearm rotation that may not be corrected with a late salvage procedure.

The second option would be to consider a salvage procedure acutely using a primary distal ulnar head replacement as described above [38] or ulnar head resection and soft tissue interposition [39].

Treatment of comminuted distal ulnar fractures

The indications for using a salvage procedure as a first option are very limited. There is nothing in the literature to suggest that excising or replacing the ulnar head acutely has a benefit over waiting to assess the final result. We therefore recommend an initial approach of restoring and maintaining the overall alignment of the ulna and DRU-joint with the later option of a salvage procedure depending on the final result.

Conclusion

The importance of the ulnar side of the wrist is being considered more carefully as more and more surgeons realize that in order to improve the outcome after distal forearm fractures, the ulnar side needs more attention. There is little scientific support to guide the management of distal ulnar fractures (Table 1). This probably reflects the historic view of the ulna being the smaller bone in the distal forearm and consequently being incorrectly ignored in comparison to the overwhelming literature regarding its larger counterpart; the radius. We strongly believe that the distal ulna always should be treated far more aggressively than we historically seem to have done in order to restore the fixed point that the hand needs in most daily activities. Without the help of strong guidelines in our extensive search (Table 1) we hope that the accepted understandings described in conjunction with our personal experiences will shed some light on how to best address, assess, investigate and treat the important distal ulnar styloid, head, neck and shaft fractures.

References

- 1.Hagert CG (1996) Current concepts of the functional anatomy of the distal radioulnar joint, including the ulnocarpal junction. In: Büchler U, Dunitz M (eds) Wrist instability, pp 15–21

- 2.Garcia-Elias M. Soft-tissue anatomy and relationships about the distal ulnar. Hand Clin. 1998;14(2):165–176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bowers W (1999) The distal radioulnar joint. In: Green D (ed) Operative hand surgery. Churchill Livingstone, New York, vol 1, pp 986–1032

- 4.af Ekenstam F, Hagert CG. The distal radioulnar joint. The influence of geometry and ligament on simulated Colles’ fracture. An experimental study. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg. 1985;19(1):27–31. doi: 10.3109/02844318509052862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.af Ekenstam F, Hagert CG. Anatomical studies on the geometry and stability of the distal radioulnar joint. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg. 1985;19(1):17–25. doi: 10.3109/02844318509052861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Palmer AK, Werner FW. The triangular fibrocartilage complex of the wrist. Anatomy and function. J Hand Surg. 1981;6A(2):153–162. doi: 10.1016/s0363-5023(81)80170-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Palmer AK. Triangular fibrocartilage complex lesions: a classification. J Hand Surg. 1989;14A(4):594–606. doi: 10.1016/0363-5023(89)90174-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hagert CG. Stabilization of the distal radioulnar joint. In: Vastamäki V, editor. Current trends in hand surgery. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 1995. pp. 197–200. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chidgey LK, Dell PC, Bittar ES, Spanier SS. Histologic anatomy of the triangular fibrocartilage. J Hand Surg. 1991;16A(6):1084–1100. doi: 10.1016/s0363-5023(10)80073-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shaw JA, Bruno A, Paul EM. Ulnar styloid fixation in the treatment of posttraumatic instability of the radioulnar joint: a biomechanical study with clinical correlation. J Hand Surg. 1990;15A(5):712–720. doi: 10.1016/0363-5023(90)90142-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.May MM, Lawton JN, Blazar PE. Ulnar styloid fractures associated with distal radius fractures: Incidence and implications for distal radioulnar joint instability. J Hand Surg. 2002;27A(6):965–971. doi: 10.1053/jhsu.2002.36525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Geissler WB, Freeland AE, Savoie FH, McIntyre LW, Whipple TL. Intracarpal soft-tissue lesions associated with an intra-articular fracture of the distal end of the radius. J Bone Joint Surg. 1996;78A(3):357–365. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199603000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oskarsson GV, Aaser P, Hjall A. Do we understand the predictive value of the ulnar styloid affection in Colles fractures. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 1997;116(6–7):341–344. doi: 10.1007/BF00433986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Catalano LW, 3rd, Cole JR, Gelberman RH, Evanoff BA, Gilula LA, Borrelli J., Jr Displaced intra-articular fractures of the distal aspect of the radius. Long-term results in young adults after open reduction and internal fixation. J Bone Joint Surg. 1997;79A(9):1290–1302. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199709000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bacorn RW, Kurtzke JF. Colles’ fracture: a study of two thousand cases from the New York State Workmans compensation board. J Bone Joint Surg. 1953;35A(3):643–658. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Frykman G. Fractures of the distal radius including sequelae-shoulder-hand-finger syndrome, disturbance in the distal radioulnar joint and impairment of nerve function: a clinical and experimental study. Acta Orthop Scand. 1967;Suppl 108:3+. doi: 10.3109/ort.1967.38.suppl-108.01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reeves B. Excision of the ulnar styloid fragment after Colles’ fracture. Int Surg. 1966;45(1):46–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Knirk JL, Jupiter JB. Intra-articular fractures of the distal end of the radius in young adults. J Bone Joint Surg. 1986;68A(5):647–659. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Buterbaugh GA, Palmer AK. Fractures and dislocations of the distal radioulnar joint. Hand Clin. 1988;4(3):361–375. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Geissler WB, Fernandez DL, Lamey DM. Distal radioulnar joint injuries associated with fractures of the distal radius. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1996;327:135–146. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199606000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Adams BD. Distal radioulnar joint instability. In: Green PD, Pederson CW, Hotchkiss RN, Wolfe SW, editors. Greens operative hand surgery. 5th. Amsterdam: Elsevier, Churchill Livingstone; 2005. p. 621. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mikic ZD. Treatment of acute injuries of the triangular fibrocartilage complex associated with distal radioulnar joint instability. J Hand Surg. 1995;20A(2):319–323. doi: 10.1016/S0363-5023(05)80033-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Roysam GS. The distal radioulnar joint in colles’ fractures. J Bone Joint Surg. 1993;75B(1):58–60. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.75B1.8421035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stewart HD, Innes AR, Burke FD. Factors affecting the outcome of Colles’ fracture: an anatomical and functional study. Injury. 1985;16(5):289–295. doi: 10.1016/0020-1383(85)90126-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lindau T, Arner M, Hagberg L. Intraarticular lesions in distal fractures of the radius in young adults. A descriptive arthroscopic study in 50 patients. J Hand Surg. 1997;22B(5):638–643. doi: 10.1016/s0266-7681(97)80364-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lindau T, Adlercreutz C, Aspenberg P. Peripheral tears of the triangular fibrocartilage complex cause distal radioulnar instability after distal radius fractures. J Hand Surg. 2000;25A(3):464–468. doi: 10.1053/jhsu.2000.6467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hauck RM, Skahen J, 3rd, Palmer AK. Classification and treatment of ulnar styloid nonunion. J Hand Surg. 1996;21A(3):418–422. doi: 10.1016/S0363-5023(96)80355-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kiyono Y, Nakatsuchi Y, Saitoh S. Ulnar-styloid nonunion and partial rupture of extensor carpi ulnaris tendon: two case reports and review of the literature. J Orthop Trauma. 2002;16(9):674–677. doi: 10.1097/00005131-200210000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xarchas KC, Yfandithis P, Kazakos K. Malunion of the ulnar styloid as a cause of ulnar wrist pain. Clin Anat. 2004;17:418–422. doi: 10.1002/ca.10235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tsukazaki T, Iwasaki K. Ulnar wrist pain after colles’ fracture. Acta Orthop Scand. 1993;64(4):462–464. doi: 10.3109/17453679308993668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Burgess RC, Watson KH. Hypertrophic ulnar styloid nonunions. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1988;228:215–217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jakab E, Ganos DL, Gagnon S. Isolated intra-articular fractures of the ulnar head. J Orthop Trauma. 1993;7(3):290–292. doi: 10.1097/00005131-199306000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tamura Y, Inoue G. Dislocation of the distal radioulnar joint associated with an intraarticular fracture of the ulnar head: report of two cases. J Orthop Trauma. 1998;12(1):68–70. doi: 10.1097/00005131-199801000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Solan MC, Rees R, Molloy S, Proctor MT. Internal fixation after intra-articular fracture of the distal ulnar. J Bone Joint Surg. 2003;85B(2):279–280. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.85B2.13459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dennison DG. Open reduction and internal locked fixation of unstable distal ulna fractures with concomitant distal radius fracture. J Hand Surg. 2007;32A(6):801–805. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2007.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ring D, McCarty LP, Campbell D, Jupiter JB. Condylar blade plate fixation of unstable fractures of the distal ulnar associated with fractures of the distal radius. J Hand Surg. 2004;29A(1):103–109. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2003.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kang HJ, Shim DJ, Yong SW, Yang GH, Hahn SB, Kang ES. Operative treatment for isolated distal ulnar shaft fracture. Yonsei Med J. 2002;43(5):631–636. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2002.43.5.631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Grechenig W, Peicha G, Fellinger M. Primary ulnar head prosthesis for the treatment of an irreparable ulnar head fracture dislocation. J Hand Surg. 2001;26B(3):269–271. doi: 10.1054/jhsb.2000.0548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Seitz WH, Jr, Raikin SM. Resection of comminuted ulna head fragments with soft tissue reconstruction when associated with distal radius fractures. Tech Hand Up Extrem Surg. 2007;11(4):224–230. doi: 10.1097/BTH.0b013e31805752f8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]