Abstract

mRNA polyadenylation is an essential step for the maturation of almost all eukaryotic mRNAs, and is tightly coupled with termination of transcription in defining the 3′-end of genes. Large numbers of human and mouse genes harbor alternative polyadenylation sites [poly(A) sites] that lead to mRNA variants containing different 3′-untranslated regions (UTRs) and/or encoding distinct protein sequences. Here, we examined the conservation and divergence of different types of alternative poly(A) sites across human, mouse, rat and chicken. We found that the 3′-most poly(A) sites tend to be more conserved than upstream ones, whereas poly(A) sites located upstream of the 3′-most exon, also termed intronic poly(A) sites, tend to be much less conserved. Genes with longer evolutionary history are more likely to have alternative polyadenylation, suggesting gain of poly(A) sites through evolution. We also found that nonconserved poly(A) sites are associated with transposable elements (TEs) to a much greater extent than conserved ones, albeit less frequently utilized. Different classes of TEs have different characteristics in their association with poly(A) sites via exaptation of TE sequences into polyadenylation elements. Our results establish a conservation pattern for alternative poly(A) sites in several vertebrate species, and indicate that the 3′-end of genes can be dynamically modified by TEs through evolution.

INTRODUCTION

mRNA polyadenylation is an essential step for the maturation of almost all eukaryotic mRNAs (1), and is tightly coupled with termination of transcription (2) and other steps of pre-mRNA processing (3,4). It involves an endonucleolytic cleavage at a polyadenylation site [poly(A) site], followed by polymerization of an adenosine tail at the 3′-end of the cleaved RNA (5). Poly(A) tails are critical for virtually every aspect of mRNA metabolism, including mRNA transport, translation and mRNA stability (6–8). Malfunction of polyadenylation has been implicated in several human diseases (9,10).

The genomic sequence surrounding a poly(A) site is referred to as the poly(A) site region. Most cis-elements involved in polyadenylation are located in the −100 to +100 nt region, with poly(A) site set at position 0 (11). Signals located in the −40 to +40 nt region are usually essential for polyadenylation, and can be considered as core elements, whereas signals located between 41 and 100 nt in upstream or downstream regions have been implicated in the modulation of polyadenylation, and can be considered as auxiliary elements (11). The nucleotide composition of human poly(A) site regions is generally T-rich, with an A-rich sequence located right before poly(A) site (12,13). A hexamer AATAAA or ATTAAA or a close variant, usually referred to as the polyadenylation signal (PAS), is typically located in the −40 to −1 nt region (13,14). T-rich element and TGTG element and its variants are typically located in the +1 to +40 nt region (11). In addition, TGTA, TATA, G-rich and C-rich elements in various upstream or downstream regions have been implicated in regulation of polyadenylation by experimental and/or bioinformatic studies (11,15,16). Phylogenetic analyses have indicated that the cis-element structure of poly(A) site is essentially conserved across amniotes, from human to chicken, but divergent in lower vertebrates, such as fish (17, Lee,J.Y. and Tian,B., unpublished data).

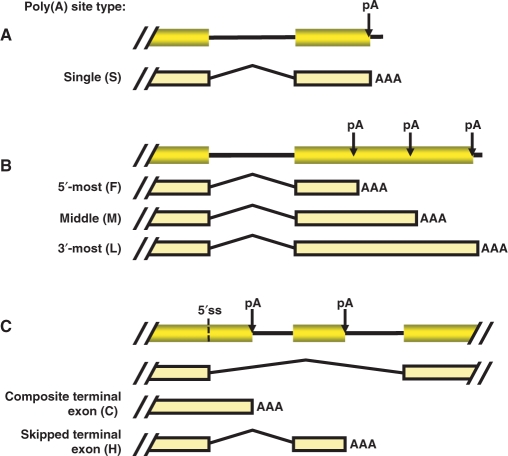

Over half of all human genes have multiple poly(A) sites (13,18), leading to alternative gene products and contributing to the complexity of the mRNA pool in human cells. Multiple poly(A) sites can be located downstream of the stop codon in the 3′-most exon (Figure 1), leading to transcripts with variable 3′-untranslated regions (UTRs), or in internal exons, leading to transcripts with variable protein products and 3′-UTRs. The latter case is also referred to as intronic polyadenylation, as poly(A) site usage is competed against by splicing (19). The selection of alternative poly(A) sites has been shown to be related to biological factors, such as development stage and cell condition, for a number of genes (20–24). Both the level of polyadenylation factors and tissue-specific usage of cis-elements have been implicated in alternative polyadenylation in different tissues (21,25,26).

Figure 1.

Schematic of alternative polyadenylation and different types of poly(A) site. Poly(A) sites are classified and named according to their location in a gene. The one letter code for each type is shown in parenthesis. (A) Single poly(A) sites (S). (B) Sites located in the 3′-most exon are classified into 5′-most site (F), middle site (M) and 3′-most site (L). (C) Sites located upstream of the 3′-most exon are considered intronic, and named composite terminal exon site (C), and skipped or hidden terminal exon sites (H), based on the gene splicing pattern. pA, poly(A) site; 5′ ss, 5′ splice site; AAA, poly(A) tail.

Transposable elements (TEs) account for at least 45% of the human genome, and play important roles in shaping the genome structure through evolution (27,28). TEs can also regulate gene expression (29,30), by providing cis-elements at promoter regions (31), giving rise to new exons (32–34) or modulating transcription (35–37). Major TE classes in the human genome are DNA transposons (DNAs), long interspersed elements (LINEs), long terminal repeat retrotransposons (LTRs) and short interspersed elements (SINEs). Each class has a number of families and subfamilies with distinct structures and consensus sequences, and are active in transposition in different periods of evolution in different species (38). While most TEs in the human genome have lost transposition activity, some are still active, including the L1 family of LINE, Alu family of SINE and SVA element (39), leading to genetic variation and causing diseases (40,41). Both L1 and Alu have also been implicated in creating poly(A) sites for certain genes (42,43).

Here, by using whole genome alignments of several amniotes, including human, mouse, rat and chicken, we set out to systematically address (i) the general trend of conservation for poly(A) sites at different locations of a gene and (ii) the roles which different classes of TEs play in the evolution of poly(A) sites.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Data sets

We used poly(A) sites from the PolyA_DB 2 database (44). These poly(A) sites were mapped by aligning poly(A/T)-tailed cDNA/ESTs with genome sequences using BLAT (45) and in-house Perl scripts (46). Briefly, the UniGene database was used to group cDNA/ESTs into genes, NCBI RefSeq and UCSC Known Gene sequences were used to identify the intron/exon structure of a gene. Adjacent poly(A) sites (<24 nt from one another) were clustered together. Poly(A) sites were classified according to their locations in the gene. The RepeatMasker program (version 3.1.8) and the RepBase database (version October 2006) were used to identify TEs in poly(A) site regions with default settings.

Mapping of orthologous poly(A) sites

To identify orthologous poly(A) sites between two species, we used pair-wise genome alignment files downloaded from the UCSC Genome Bioinformatics Site. We required reciprocal best matches for a pair of orthologous poly(A) sites according to the distance from one site to the other in the genome alignment, and that the two sites are located within a 24 nt window as depicted in Supplementary Figure 1A. We found that changing the window size did not lead to significant change of the number of mapped orthologous sites (Supplementary Figure 1B), suggesting robustness of this method. In addition, almost none of the mapped orthologous poly(A) sites belonged to genes that were in different NCBI HomoloGene orthologous groups (data not shown), suggesting high accuracy.

RESULTS

Conservation patterns of poly(A) sites in human, mouse, rat and chicken

Alternative polyadenylation is a widespread mechanism for genes to produce transcript variants (13,47). Poly(A) sites can be classified into different types based on their locations in a gene (Figure 1). For simplicity, we also use one letter code to refer to a type in this study. A poly(A) site located in a 3′-most exon that contains only one poly(A) site is named single or constitutive site (S type); poly(A) sites located in 3′-most exons containing multiple poly(A) sites are named F type (the first or 5′-most), L type (the last, or 3′-most) or M type (middle ones between F and L). In addition, poly(A) sites located upstream of 3′-most exons are considered as intronic sites, which include composite terminal exon sites (C) and skipped or hidden terminal exon sites (H).

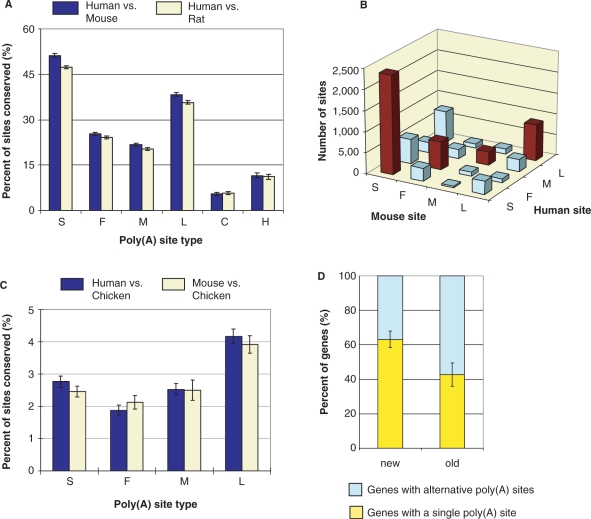

To understand how poly(A) sites have evolved, we mapped orthologous poly(A) sites using human, mouse, rat and chicken poly(A) sites and pair-wise genome alignments between these organisms (see Materials and Methods and Supplementary Figure 1 for detail). We focused on these aminotes because there are a large number of poly(A/T)-tailed cDNA/ESTs available for mapping poly(A) sites in their genomes and previous bioinformatic studies have indicated that the cis-element structure of poly(A) site is essentially the same across aminotes (17, Lee,J.Y. and Tian,B., unpublished data). Of 37 591 human sites, 11 255 (30%) were found to be conserved in mouse, 10 526 (28%) in rat and 922 (2%) in chicken. As shown in Figure 2A, human versus mouse and human versus rat conservation patterns are largely identical. The S type sites are the most conserved among all types, the L type sites are significantly more conserved than F or M type sites and intronic sites are the least conserved ones (Figure 2A). Of the intronic sites, H type sites are more conserved than C type sites. For conserved sites in 3′-most exons, conservation of poly(A) site type is statistically significant (P = 2.2 × 10−16, Chi-squared test, Figure 2B), despite that some human sites are mapped to a different type than their mouse orthologs and vice versa. The same conclusions can be drawn from analyses of mouse versus human and mouse versus rat sites (Supplementary Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Conservation of human poly(A) sites in mouse, rat and chicken. (A) Percent of human poly(A) sites of different types that are conserved in mouse and rat. P-values (Chi-squared test) for difference in conservation between F and L types are 3.52 × 10−67 for human versus mouse, and 3.72 × 10−56 for human versus rat. Error bars are standard deviation. (B) Conservation of poly(A) site type between human and mouse orthologous poly(A) sites (P < 2.2 × 10−16, Chi-squared test). (C) Percent of human and mouse poly(A) sites conserved in chicken. P-values (Chi-squared test) for difference in conservation between F and L types are 1.34 × 10−16 for human versus chicken and 4.39 × 10−7 for mouse versus chicken. (D) Percent of genes with alternative poly(A) sites for genes with orthologs in chicken (named ‘old’, 8140 in total) and genes without orthologs in chicken (named ‘new’, 4284 in total). P-value (Chi-squared test) for the difference is 8.39 × 10−145.

The fact that L type sites are more conserved than F or M type sites indicates that downstream poly(A) sites are better preserved in evolution and gain or loss of poly(A) sites are more likely to take place in upstream poly(A) sites. To further explore this with a broader evolutionary perspective, we carried out human versus chicken and mouse versus chicken poly(A) site comparisons. As shown in Figure 2C, both comparisons had the same conservation pattern. Interestingly, the difference between L and F is more conspicuous than those from comparisons of mammals, suggesting that conservation of 3′-most poly(A) sites are more discernable in genes with longer evolutionary history. Furthermore, human and mouse S type sites are relatively less conserved in chicken than in mammals, suggesting that longer evolution may bring about more poly(A) sites. To explore this hypothesis, we divided human genes into two groups, ones with orthologs in chicken (named ‘old’ genes) and ones without (named ‘new’ genes), and examined the frequency of alternative polyadenylation in each group. As shown in Figure 2D, a significantly higher proportion of old genes have alternative poly(A) sites than new genes (P = 8.39 × 10−145, Chi-squared test), indicating that genes, in general, gain poly(A) sites through evolution.

TEs and poly(A) sites

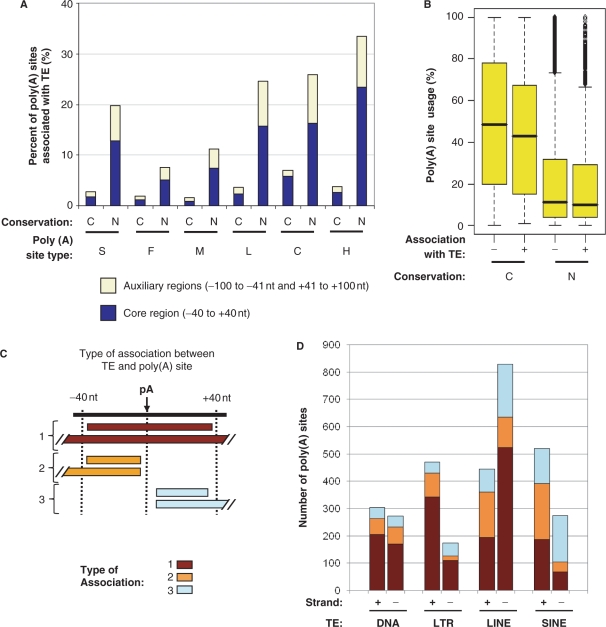

A large number of human poly(A) sites are not conserved in mouse, a sizable fraction of which is due to lack of genome alignments (data not shown). Since TEs have been implicated in giving rise to new exon sequences in evolution, we wanted to know how TEs might be responsible for species-specific poly(A) sites. Using the RepeatMasker program and the RepBase database, we examined poly(A) sites that are associated with four classes of TEs, i.e. DNAs, LINEs, LTRs and SINEs. A TE can contain a poly(A) site or contribute cis-elements to a poly(A) site. For the latter case, we required the distance between a poly(A) site and a TE to be within 40 nt, as essential cis-elements involved in polyadenylation are typically located in the −40 to +40 nt core region (11). In sum, 3188 human poly(A) sites from 2565 genes, corresponding to ∼8% of all poly(A) sites and ∼16% of all genes surveyed, were found to be associated with TEs. As shown in Figure 3A, we found that human poly(A) sites that are not conserved in mouse are associated with TEs to a much greater extent than those conserved ones. In fact, ∼94% of TE-associated sites are nonconserved in mouse. Conversely, ∼5% of mouse poly(A) sites from ∼7% of genes surveyed are associated with TEs, of which ∼93% are not conserved in human (data not shown). This result indicates that TEs can significantly contribute to creation or modulation of poly(A) sites in evolution, and are responsible for species-specific poly(A) sites.

Figure 3.

Poly(A) sites and TEs. (A) Percent of human poly(A) sites associated with TEs for different types of conserved and nonconserved sites. Both TEs overlapping with poly(A) site regions in the auxiliary regions (−100 to −41nt and +41 to +100 nt) and core region are shown. (B) Usage of different types of poly(A) sites. Percent of poly(A) site usage is based on the number of supporting ESTs for a poly(A) site compared with the number of ESTs for all poly(A) sites of the same gene. (C) Schematic of three types of association between TE and poly(A) site. The top horizontal line represents a poly(A) site region with the arrow pointing to a poly(A) site. TEs are represented by horizontal bars. Three types of placement of a TE in a poly(A) site region are shown. In type 1, a TE contains a poly(A) site and adjacent upstream and downstream regions; in types 2 and 3, only the upstream or downstream region of a poly(A) site is contained in a TE. The type number is indicated in the graph. (D) Number of poly(A) sites associated with four classes of TEs. The three types of association and TE strand are indicated.

As shown in Figure 3A, nonconserved intronic poly(A) sites are associated with TEs more frequently than nonconserved sites in 3′-most exons, with the H type sites being associated with TEs to the greatest extent. Interestingly, nonconserved S and L type sites are associated with TEs more frequently than F and M type sites. Since these sites are the 3′-most sites for genes, this finding indicates that TEs can play a significant role in defining the 3′-end boundary of a gene. Similar trends can be discerned for poly(A) sites overlapping with TEs in the −100 to −41nt and +41 to +100nt auxiliary regions (Figure 3A), which generally contain regulatory elements for polyadenylation. Some conserved poly(A) sites are also associated with TEs, indicating selection for their function through evolution.

To understand how TE-associated poly(A) sites are utilized, we examined the usage of different types of poly(A) sites using the number of EST sequences supporting for poly(A) site. While this method is not considered quantitative enough for assessing the usage of individual poly(A) sites, it can reveal the general usage trend for a set of sites (21). As shown in Figure 3B, nonconserved sites are much less frequently used than conserved sites for both poly(A) sites associated with TEs and those not. TE-associated poly(A) sites appear to be slightly less frequently used than other sites in both conserved and nonconserved groups. Since conserved TE-associated poly(A) sites have longer evolutionary histories than nonconserved ones, this result suggests that TEs are gradually fixed in evolution for their role in polyadenylation, presumably undergoing optimization of polyadenylation activity by mutation.

For the four major classes of TEs in the human genome, the number of TEs-associated with poly(A) sites follows the order LINE > SINE > LTR > DNA (Table 1), which approximately correlates with their occurrence in the human genome (27). We further examined three types of association based on the location of TE in poly(A) site region, including the whole −40 to +40nt core region, the −40 to −1nt core upstream region and the +1 to +40nt core downstream region, as illustrated in Figure 3C. As shown in Figure 3D, different TE classes are associated with poly(A) sites differently. While most DNAs and LTRs tend to contain whole poly(A) site region, a large fraction of LINEs and SINEs are located either upstream or downstream of poly(A) sites, suggesting contribution of cis-elements, with SINEs being more conspicuous for this trend. In addition, strong strand biases can be discerned for LTRs, LINEs and SINEs.

Table 1.

Human poly(A) sites are associated with different classes of TEs

| TE class | No. of TE families | No. of TE subfamilies | No. of poly(A) sites | Top families | No. of conserved poly(A) sites | No. of nonconserved poly(A) sites |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DNA | 11 | 116 | 572 | MER1_type | 31 | 272 |

| MER2_type | 4 | 141 | ||||

| LTR | 6 | 215 | 639 | MaLR | 12 | 280 |

| ERV1 | 3 | 216 | ||||

| ERVL | 11 | 77 | ||||

| ERVK | 0 | 33 | ||||

| LINE | 4 | 88 | 1257 | L1 | 30 | 827 |

| L2 | 50 | 302 | ||||

| SINE | 3 | 28 | 783 | MIR | 37 | 407 |

| Alu | 0 | 338 |

Conservation is based on the human and mouse comparison. Top families are those accounting for >5% of poly(A) sites that are associated with a TE class.

Poly(A) sites in terminal regions of DNAs and LTRs can be adopted by human genes

We found that poly(A) sites associated with DNAs and LTRs are primarily located in terminal regions of these elements, namely the terminal inverted repeats (TIRs) in DNAs and terminal LTR sequences in LTRs. However, as shown in Figure 3D, while the plus and minus strands of TIR are associated with poly(A) sites with similar frequencies, a strong bias to the plus strand of LTR can be discerned. This result is consistent with PAS occurrence and poly(A) site prediction by polyA_SVM (48) and polyadq (49) for TIR and LTR sequences, as shown in Supplementary Figure 3A–D, in which top DNA and LTR families and subfamilies with respect to poly(A) site association are analyzed (MER33 subfamily of MER1_type and Tigger 1 subfamily of MER2_type for DNA and MLT1C subfamily of MaLR and MER21C subfamily of ERV1 for LTR). Thus, poly(A) sites in human genes that are associated with DNAs and LTRs are generally endogenous poly(A) sites in these TE elements that have been adopted through evolution.

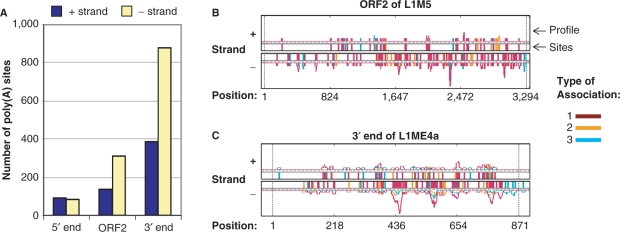

A large number of poly(A) sites are derived from both strands of L1

The L1 family of LINE accounts for ∼17% of the human genome, the highest among all TE families and has been active for the last ∼170 million years (MYR) (50). Not surprisingly, L1 is associated with poly(A) sites with the highest frequency among all TE families. Many internal poly(A) sites of L1 have been reported, which has been implicated in the modulation of its retrotransposition activity (42). A full-length L1 is composed of 5′-UTR, ORF1, ORF2 and 3′-UTR. However, L1 sequences in the human genome are often truncated at the 5′-end due to inefficient reverse transcription during retrotransposition (51). Consistently, the number of poly(A) sites associated with these sequences follows the order: 3′-end (3′-UTR) > ORF2 > 5′-end (5′-UTR + ORF1) (Figure 4A). As shown for the examples of top L1 subfamilies, ORF2 of L1M5 and 3′-end region of L1ME4a, poly(A) sites in ORF2 and 3′-end region are diffusely distributed (Figure 4B and C), except for several ‘hot spots’ on the minus strand of the 3′-end region. Interestingly, while ORF2 and 3′-end region contain much more AATAA/ATTAAA and other PAS hexamers on the plus strand than the minus strand (Supplementary Figure 3E and F), presumably due to their A-rich content, more poly(A) sites are associated with minus strands than plus strands, with a ratio of 2 : 1 (Figure 4A). This bias is in good agreement with previous reports that indicated preferential placement of L1 sequences in antisense orientation of host genes with a ratio of ∼2 (52). We further analyzed ORF2 and 3′-end sequences by PolyA_SVM, which uses 15 cis-elements surrounding poly(A) site for prediction (48). We found that more poly(A) sites can actually be predicted on the minus strand than on the plus strand (7 versus 3) for ORF2, and same number of sites for the 3′-end region (Supplementary Figure 3E and F). Thus, other cis-elements may exist on the minus strand that lead to higher occurrence of poly(A) sites than the plus strand, despite fewer PAS hexamers. Further experimental analysis is needed to confirm this hypothesis. In addition, several regions of L1 do not contain PAS or predicted poly(A) sites, but are associated with poly(A) sites with high frequency, suggesting that they may contain favorable sequences that can give rise to cis-elements for polyadenylation through mutations.

Figure 4.

Poly(A) sites and L1. (A) Number of poly(A) sites associated with plus and minus strands of three L1 regions, i.e. 5′-end, ORF2 and 3′-end. (B) Distribution of poly(A) sites in ORF2 of L1M5 subfamily. The poly(A) sites are indicated by vertical bars and also shown in a profile, which is essentially a smoothed histogram of poly(A) site occurrence. The profile is smoothed by a 11 nt window, i.e. value of a position is the average of 11nt surrounding the position. Three association types (illustrated in Figure 3C) are represented by different colors, as indicated in the graph. The poly(A) site position for type 1 is actual poly(A) site location, whereas the position for types 2 or 3 is location of the closest nucleotide in TE to its associated poly(A) site. Additional 40 nt are added to both 5′- and 3′-ends to illustrate poly(A) sites located upstream or downstream of TE. Vertical dotted lines are the start and end of TE. (C) Distribution of poly(A) sites in 3′-end of L1ME4a subfamily.

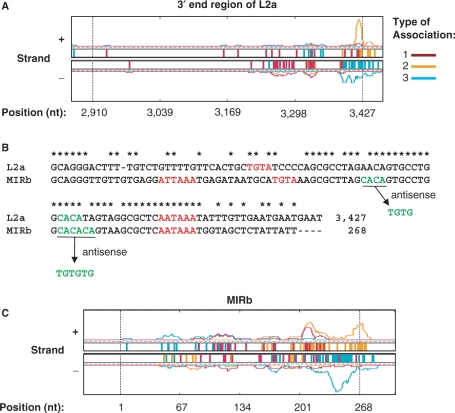

The homologous 3′-end regions of L2 and MIR contain cis-elements for polyadenylation

L2 is the second top LINE associated with poly(A) sites. Most associated poly(A) sites are located within or near its 3′-end region, as shown for L2a, the top subfamily of L2 (Figure 5A). Interestingly, the last 50 nt region of its plus strand tends to be located upstream of poly(A) site, whereas the minus strand of this region tends to be located downstream of poly(A) site (Figure 5A). Consistent with this observation, this region contains an AATAAA PAS and a TGTA element on the plus strand and a TGTG element on the minus strand (Figure 5B). Since the 3′-end region of L2 is highly homologous to the 3′-end region of Mammalian-wide interspersed repeat (MIR), a tRNA-derived SINE that is thought to be active ∼130 MYR ago, in the same period as L2 (53,54), it is not surprising to see that MIR has a similar trend for poly(A) site association (Figure 5C). For example, MIRb, the top MIR subfamily, contains both ATTAAA and AATAAA PAS and a TGTA element on the plus strand and two TGTG elements on the minus strand (Figure 5B). Thus, MIR and L2 can bring either upstream or downstream cis-elements for polyadenylation to the genome, and give rise to new poly(A) sites. Notably, consistent with their evolutionary history, MIR and L2 together account for about half of the conserved TE-associated poly(A) sites, indicating their significant contribution to poly(A) site evolution in mammals.

Figure 5.

Poly(A) sites and L2 and MIR. (A) Distribution of poly(A) sites in the 3′-end region of L2a subfamily of L2. (B) Alignment of the 3′-end region of L2a with MIRb. AATAAA, ATTAAA, TGTA are shown in green. Identical nucleotides are indicated by asterisks. (C) Distribution of poly(A) sites in MIRb subfamily of MIR. See the legend of Figure 4B for description of (A) and (C).

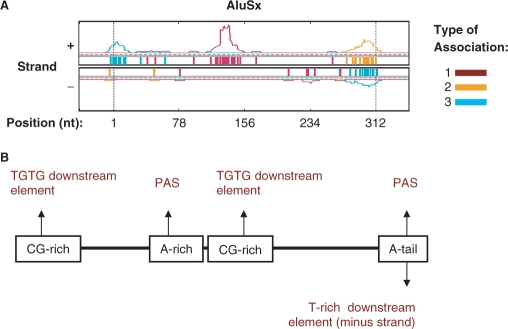

Four modes of poly(A) site association for Alu

Alu has the highest copy number in the human genome among all TE families, and is the second top SINE associated with poly(A) sites, after MIR. Alu sequences are derived from 7SL RNA elements, and are composed of two related monomers separated by a middle A-rich region. An Alu sequence has a RNA polymerase III promoter located at the 5′-end, and a poly(A) sequence at the 3′-end that is required for retrotransposition (55). For the top subfamily, AluSx, four hot spots can be discerned (Figure 6A). The 5′-end region of AluSx tends to be located downstream of poly(A) sites. This region is rich in CG. Further examination of poly(A) sites associated with this region indicated that this region tends to give rise to TG elements via transition of C to T. Interestingly, CG dinucleotides in Alu were found to have about 10 times higher mutation rate than other dinucleotides in the sequence (56,57). Thus, despite that the consensus sequence of the 5′-end region does not have apparent cis-elements for polyadenylation, it has propensity to mutate to poly(A) site downstream elements. A second hot spot is located in the middle region of the plus strand. This region contains the middle A-rich sequence followed by a CG-rich sequence that is highly similar to the 5′-end region described above. Further examination indicated that the middle A-rich sequence tends to mutate to PAS and the CG-rich sequence tends to mutate to TG elements. Consistent with these findings, poly(A) sites associated with this region are completely encoded by Alu sequences. The third and fourth hot spots correspond to the plus strand and minus strand of the 3′-end poly(A) tail sequence, respectively. Not surprisingly, this poly(A) tail sequence can give rise to upstream PAS hexamers when in the sense orientation, or downstream T-rich elements when in the antisense orientation. Thus, despite lack of cis-elements for polyadenylation in its consensus, Alu sequences provide favorable breeding ground for new poly(A) sites by four mechanisms through mutations, as illustrated in Figure 6B. Its contribution to the 3′-end definition of human genes can be highly significant due to its widespread nature in the human genome.

Figure 6.

Poly(A) sites and Alu. (A) Distribution of poly(A) sites in AluSx subfamily of Alu. See the legend of Figure 4B for description of the graph. (B) Schematic of mechanisms by which different regions of Alu give rise to cis-elements for polyadenylation.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we used whole genome alignments to identify conserved poly(A) sites across species. The high sensitivity and selectivity of this approach are supported by the results that using different window sizes for mapping orthologous sites only made minor differences, and the mapping result was in good agreement with the gene ortholog information based on coding sequences. We found that single poly(A) sites are much more conserved than alternative poly(A) sites, which agrees with what was reported by Ara et al. (58). However, our finding that the 3′-most poly(A) sites are more conserved than upstream ones is inconsistent with what was reported by Ara et al. in which poly(A) sites distal to the stop codon were found to be less conserved than those proximal ones. This can be partly attributable to differences in mapping conserved sites. While both methods use a window for finding conserved poly(A) sites (30 nt in their case, and 24 in our case), Ara et al. additionally required that PAS to be perfectly aligned. This can make conserved poly(A) sites proximal to the stop codon more easily detected, as sequence conservation in the 3′-UTR is generally better in the 5′-region than in the 3′-region. This bias can be further exacerbated by the fact that PAS are located in an AT-rich low complexity region, for which sequence alignment tools may not perform well in aligning short fragments, for example, PAS hexamers. By contrast, our method is not bound by this restriction, and does not have the bias to 5′-poly(A) sites. As such, for comparable numbers of poly(A) sites, Ara et al. found ∼13% but we found ∼30% are conserved between human and mouse. In addition, Ara et al. divided alternative poly(A) sites into proximal and distal groups, which correspond to F+M and L+M types, respectively, in this study. Thus, the discrepancy between our results and theirs can also be caused by M type poly(A) sites, which is less conserved than F or L.

Previous studies have implicated a number of TEs in bringing poly(A) sites to endogenous genes (42,43). Our comprehensive analysis in this study establishes poly(A) site association patterns for four classes of TEs. Three modes of TE-mediated poly(A) site creation were detected: (i) some poly(A) sites are encoded by TEs and utilized by endogenous genes, such as poly(A) sites in the TIR region of DNAs, the LTR region of LTRs and various regions of L1; (ii) some poly(A) sites were created by combining cis-elements from TEs with those in the genome, such as the 3′-end regions of L2 and MIR and (iii) some poly(A) sites were derived from TE regions that have high propensity to give rise to poly(A) sites by mutations, such as the 5′-end, middle and 3′-end regions of Alu. The diverse pathways to create poly(A) site suggests that the 3′-end of genes can be dynamically modified in evolution. Conceivably, this can have a significant impact on the evolution of 3′-UTRs and their cis-elements. On this note, TEs in 3′-UTRs have been linked to microRNA target sites and AU-rich elements (59,60), and have been involved in regulation of RNA localization via RNA editing (61).

TEs are associated with nonconserved poly(A) sites more frequently than with conserved ones, indicating that they play important roles in setting lineage specific polyadenylation patterns. However, it is notable that only those TEs that have sufficient degree of similarity to their consensus sequences can be examined in this study, and ancient TEs, which have diverged beyond recognition by current computational methods, are not detected. In this regard, the fact that all TE classes analyzed in this study have some level of association with poly(A) sites makes it plausible that many conserved poly(A) sites are also associated with TEs, but their sequence divergence has made them not recognizable by the RepeatMasker program. Given the widespread nature of TEs and their extensive roles in shaping the genomes through evolution, it is conceivable that TEs have played a significant role in poly(A) site evolution and defining the 3′-end of genes.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary Data are available at NAR Online.

FUNDING

National Institutes of Health (R01 GM084089 to B.T.). Funding for open access charge: R01 GM084089.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

We thank Michael Tsai for technical help at early stage of this project.

REFERENCES

- 1.Edmonds M. A history of poly A sequences: from formation to factors to function. Prog. Nucleic Acid Res. Mol. Biol. 2002;71:285–389. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6603(02)71046-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Buratowski S. Connections between mRNA 3′ end processing and transcription termination. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2005;17:257–261. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2005.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Proudfoot NJ, Furger A, Dye MJ. Integrating mRNA processing with transcription. Cell. 2002;108:501–512. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00617-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bentley DL. Rules of engagement: co-transcriptional recruitment of pre-mRNA processing factors. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2005;17:251–256. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2005.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Colgan DF, Manley JL. Mechanism and regulation of mRNA polyadenylation. Genes Dev. 1997;11:2755–2766. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.21.2755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jacobson A, Peltz SW. Interrelationships of the pathways of mRNA decay and translation in eukaryotic cells. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1996;65:693–739. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.65.070196.003401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sachs AB, Sarnow P, Hentze MW. Starting at the beginning, middle and end: translation initiation in eukaryotes. Cell. 1997;89:831–838. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80268-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wickens M, Anderson P, Jackson RJ. Life and death in the cytoplasm: messages from the 3′ end. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 1997;7:220–232. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(97)80132-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen JM, Ferec C, Cooper DN. A systematic analysis of disease-associated variants in the 3′ regulatory regions of human protein-coding genes I: general principles and overview. Hum. Genet. 2006;120:1–21. doi: 10.1007/s00439-006-0180-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Danckwardt S, Hentze MW, Kulozik AE. 3′ end mRNA processing: molecular mechanisms and implications for health and disease. EMBO J. 2008;27:482–498. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hu J, Lutz CS, Wilusz J, Tian B. Bioinformatic identification of candidate cis-regulatory elements involved in human mRNA polyadenylation. RNA. 2005;11:1485–1493. doi: 10.1261/rna.2107305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Legendre M, Gautheret D. Sequence determinants in human polyadenylation site selection. BMC Genomics. 2003;4:7. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-4-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tian B, Hu J, Zhang H, Lutz CS. A large-scale analysis of mRNA polyadenylation of human and mouse genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:201–212. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Beaudoing E, Freier S, Wyatt JR, Claverie JM, Gautheret D. Patterns of variant polyadenylation signal usage in human genes. Genome Res. 2000;10:1001–1010. doi: 10.1101/gr.10.7.1001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gilmartin GM. Eukaryotic mRNA 3′ processing: a common means to different ends. Genes Dev. 2005;19:2517–2521. doi: 10.1101/gad.1378105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhao J, Hyman L, Moore C. Formation of mRNA 3′ ends in eukaryotes: mechanism, regulation and interrelationships with other steps in mRNA synthesis. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 1999;63:405–445. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.63.2.405-445.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Salisbury J, Hutchison KW, Graber JH. A multispecies comparison of the metazoan 3′-processing downstream elements and the CstF-64 RNA recognition motif. BMC Genomics. 2006;7:55. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-7-55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yan J, Marr TG. Computational analysis of 3′-ends of ESTs shows four classes of alternative polyadenylation in human, mouse and rat. Genome Res. 2005;15:369–375. doi: 10.1101/gr.3109605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tian B, Pan Z, Lee JY. Widespread mRNA polyadenylation events in introns indicate dynamic interplay between polyadenylation and splicing. Genome Res. 2007;17:156–165. doi: 10.1101/gr.5532707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Peterson ML. Mechanisms controlling production of membrane and secreted immunoglobulin during B cell development. Immunol Res. 2007;37:33–46. doi: 10.1007/BF02686094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang H, Lee JY, Tian B. Biased alternative polyadenylation in human tissues. Genome Biol. 2005;6:R100. doi: 10.1186/gb-2005-6-12-r100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhu H, Zhou HL, Hasman RA, Lou H. Hu proteins regulate polyadenylation by blocking sites containing U-rich sequences. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:2203–2210. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609349200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hall-Pogar T, Zhang H, Tian B, Lutz CS. Alternative polyadenylation of cyclooxygenase-2. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:2565–2579. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Phillips C, Jung S, Gunderson SI. Regulation of nuclear poly(A) addition controls the expression of immunoglobulin M secretory mRNA. EMBO J. 2001;20:6443–6452. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.22.6443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Edwalds-Gilbert G, Veraldi KL, Milcarek C. Alternative poly(A) site selection in complex transcription units: means to an end? Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:2547–2561. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.13.2547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McMahon KW, Hirsch BA, MacDonald CC. Differences in polyadenylation site choice between somatic and male germ cells. BMC Mol. Biol. 2006;7:35. doi: 10.1186/1471-2199-7-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lander ES, Linton LM, Birren B, Nusbaum C, Zody MC, Baldwin J, Devon K, Dewar K, Doyle M, FitzHugh W, et al. Initial sequencing and analysis of the human genome. Nature. 2001;409:860–921. doi: 10.1038/35057062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smit AF. Interspersed repeats and other mementos of transposable elements in mammalian genomes. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 1999;9:657–663. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(99)00031-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Medstrand P, van de Lagemaat LN, Dunn CA, Landry JR, Svenback D, Mager DL. Impact of transposable elements on the evolution of mammalian gene regulation. Cytogenet. Genome. Res. 2005;110:342–352. doi: 10.1159/000084966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.van de Lagemaat LN, Landry J.-R, Mager DL, Medstrand P. Transposable elements in mammals promote regulatory variation and diversification of genes with specialized functions. Trends Genet. 2003;19:530–536. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2003.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang T, Zeng J, Lowe CB, Sellers RG, Salama SR, Yang M, Burgess SM, Brachmann RK, Haussler D. Species-specific endogenous retroviruses shape the transcriptional network of the human tumor suppressor protein p53. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:18613–18618. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703637104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang XH, Chasin LA. Comparison of multiple vertebrate genomes reveals the birth and evolution of human exons. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:13427–13432. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603042103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sorek R. The birth of new exons: mechanisms and evolutionary consequences. RNA. 2007;13:1603–1608. doi: 10.1261/rna.682507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sela N, Mersch B, Gal-Mark N, Lev-Maor G, Hotz-Wagenblatt A, Ast G. Comparative analysis of transposed element insertion within human and mouse genomes reveals Alu's unique role in shaping the human transcriptome. Genome Biol. 2007;8:R127. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-6-r127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sironi M, Menozzi G, Comi GP, Cereda M, Cagliani R, Bresolin N, Pozzoli U. Gene function and expression level influence the insertion/fixation dynamics of distinct transposon families in mammalian introns. Genome Biol. 2006;7:R120. doi: 10.1186/gb-2006-7-12-r120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mariner PD, Walters RD, Espinoza CA, Drullinger LF, Wagner SD, Kugel JF, Goodrich JA. Human Alu RNA is a modular transacting repressor of mRNA transcription during heat shock. Mol. Cell. 2008;29:499–509. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Han JS, Szak ST, Boeke JD. Transcriptional disruption by the L1 retrotransposon and implications for mammalian transcriptomes. Nature. 2004;429:268–274. doi: 10.1038/nature02536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wicker T, Sabot F, Hua-Van A, Bennetzen JL, Capy P, Chalhoub B, Flavell A, Leroy P, Morgante M, Panaud O, et al. A unified classification system for eukaryotic transposable elements. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2007;8:973–982. doi: 10.1038/nrg2165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mills RE, Bennett EA, Iskow RC, Devine SE. Which transposable elements are active in the human genome? Trends Genet. 2007;23:183–191. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2007.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bennett EA, Coleman LE, Tsui C, Pittard WS, Devine SE. Natural genetic variation caused by transposable elements in humans. Genetics. 2004;168:933–951. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.031757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Belancio VP, Hedges DJ, Deininger P. Mammalian non-LTR retrotransposons: for better or worse, in sickness and in health. Genome Res. 2008;18:343–358. doi: 10.1101/gr.5558208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Perepelitsa-Belancio V, Deininger P. RNA truncation by premature polyadenylation attenuates human mobile element activity. Nat Genet. 2003;35:363–366. doi: 10.1038/ng1269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Roy-Engel AM, El-Sawy M, Farooq L, Odom GL, Perepelitsa-Belancio V, Bruch H, Oyeniran OO, Deininger PL. Human retroelements may introduce intragenic polyadenylation signals. Cytogenet. Genome Res. 2005;110:365–371. doi: 10.1159/000084968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lee JY, Yeh I, Park JY, Tian B. PolyA_DB 2: mRNA polyadenylation sites in vertebrate genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:D165–168. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kent WJ. BLAT—the BLAST-like alignment tool. Genome Res. 2002;12:656–664. doi: 10.1101/gr.229202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lee JY, Park JY, Tian B. Identification of mRNA polyadenylation sites in genomes using cDNA sequences, expressed sequence tags and trace. Methods Mol. Biol. 2008;419:23–37. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-033-1_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Beaudoing E, Gautheret D. Identification of alternate polyadenylation sites and analysis of their tissue distribution using EST data. Genome Res. 2001;11:1520–1526. doi: 10.1101/gr.190501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cheng Y, Miura RM, Tian B. Prediction of mRNA polyadenylation sites by support vector machine. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:2320–2325. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tabaska JE, Zhang MQ. Detection of polyadenylation signals in human DNA sequences. Gene. 1999;231:77–86. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(99)00104-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Khan H, Smit A, Boissinot S. Molecular evolution and tempo of amplification of human LINE-1 retrotransposons since the origin of primates. Genome Res. 2006;16:78–87. doi: 10.1101/gr.4001406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Babushok DV, Kazazian H.H., Jr Progress in understanding the biology of the human mutagen LINE-1. Hum Mutat. 2007;28:527–539. doi: 10.1002/humu.20486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Szak ST, Pickeral OK, Makalowski W, Boguski MS, Landsman D, Boeke JD. Molecular archeology of L1 insertions in the human genome. Genome Biol. 2002;3 doi: 10.1186/gb-2002-3-10-research0052. research0052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Giorgio Matassi DL, Giorgio Bernardi Distribution of the mammalian-wideinterspersed repeats (MIRs) in the isochores of the human genome. FEBS J. 1998;439:63–65. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)01338-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Smit AF, Riggs AD. MIRs are classic, tRNA-derived SINEs that amplified before the mammalian radiation. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:98–102. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.1.98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dewannieux M, Heidmann T. Role of poly(A) tail length in Alu retrotransposition. Genomics. 2005;86:378–381. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2005.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Labuda D, Striker G. Sequence conservation in Alu evolution. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989;17:2477–2491. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.7.2477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Batzer MA, Kilroy GE, Richard PE, Shaikh TH, Desselle TD, Hoppens CL, Deininger PL. Structure and variability of recently inserted Alu family members. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:6793–6798. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.23.6793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ara T, Lopez F, Ritchie W, Benech P, Gautheret D. Conservation of alternative polyadenylation patterns in mammalian genes. BMC Genomics. 2006;7:189. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-7-189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Smalheiser NR, Torvik VI. Mammalian microRNAs derived from genomic repeats. Trends Genet. 2005;21:322–326. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2005.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.An HJ, Lee D, Lee KH, Bhak J. The association of Alu repeats with the generation of potential AU-rich elements (ARE) at 3′ untranslated regions. BMC Genomics. 2004;5:97. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-5-97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chen LL, DeCerbo JN, Carmichael GG. Alu element-mediated gene silencing. EMBO J. 2008;27:1694–1705. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.