Abstract

Postembryonic development in plants depends on the activity of the shoot apical meristem (SAM) and root apical meristem (RAM). In Arabidopsis thaliana, CLAVATA signaling negatively regulates the size of the stem cell population in the SAM by repressing WUSCHEL. In other plants, however, studies of factors involved in stem cell maintenance are insufficient. Here, we report that two proteins closely related to CLAVATA3, FLORAL ORGAN NUMBER2 (FON2) and FON2-LIKE CLE PROTEIN1 (FCP1/Os CLE402), have functionally diversified to regulate the different types of meristem in rice (Oryza sativa). Unlike FON2, which regulates the maintenance of flower and inflorescence meristems, FCP1 appears to regulate the maintenance of the vegetative SAM and RAM. Constitutive expression of FCP1 results in consumption of the SAM in the vegetative phase, and application of an FCP1 CLE peptide in vitro disturbs root development by misspecification of cell fates in the RAM. FON1, a putative receptor of FON2, is likely to be unnecessary for these FCP1 functions. Furthermore, we identify a key amino acid residue that discriminates between the actions of FCP1 and FON2. Our results suggest that, although the basic framework of meristem maintenance is conserved in the angiosperms, the functions of the individual factors have diversified during evolution.

INTRODUCTION

The body plan of plants after embryogenesis is governed by the function of shoot and root tip meristems that are generated in the embryo. Other meristems, such as axillary and branch meristems, cells of which are ultimately derived from apical meristems, also contribute to the plant architecture. Stem cells within each meristem are self-maintaining and produce founder cells for organ and tissue differentiation. The stem cells are maintained in a specialized cell environment, termed the stem cell niche, in both the shoot apical meristem (SAM) and the root apical meristem (RAM) (Stahl and Simon, 2005; Scheres, 2007). The identity of the stem cell is regulated by the signals that are originated from the organizing center in the SAM and the quiescent center in the RAM.

In Arabidopsis thaliana, the stem cell population in the SAM is maintained by a regulatory feedback loop comprising the WUSCHEL (WUS) and CLAVATA (CLV) genes (Brand et al., 2000; Schoof et al., 2000; Reddy and Meyerowitz, 2005; Müller et al., 2006). WUS, which is expressed in the organizing center, promotes stem cell identity in the cells overlaying its expression domain through an unknown mechanism (Mayer et al., 1998; Schoof et al., 2000). WUS encodes a transcription factor with a novel homeodomain, whereas the CLV genes encode proteins that constitute a signaling pathway (Clark et al., 1997; Mayer et al., 1998; Fletcher et al., 1999; Jeong et al., 1999). CLV signaling negatively regulates the size of the stem cell population by repressing WUS. CLV3 encodes a secreted protein with a conserved CLE domain (Fletcher et al., 1999). A peptide of 12 amino acids processed from the CLE domain is thought to be an active signaling molecule that functions as a putative ligand for a receptor complex composed of CLV1 and CLV2 (Kondo et al., 2006). The CLE peptide of CLV3 binds directly to the extracellular domain of CLV1 in vitro (Ogawa et al., 2008). Severe mutations in the CLV1 and CLV3 genes cause enlargement of the SAM and floral meristem (FM), resulting in a fasciated stem and an increase in the number of flowers and floral organs (Clark et al., 1993, 1995). Conversely, overexpression of CLV3 induces meristem termination, resulting in a failure of further development after the initiation of a few leaves (Brand et al., 2000; Müller et al., 2006). In vitro application of the CLV3 peptide induces consumption of meristems in the shoot (Kondo et al., 2006). Thus, CLV3 acts as a negative regulator of stem cell maintenance in the aerial meristems in both the vegetative and reproductive phases. Recently, it was shown that a receptor kinase, CORYNE, is also involved in perception of the CLV3 signal, independently of CLV1 (Müller et al., 2008).

Although organization of the stem cell niche differs in the SAM and RAM, factors involved in the regulation of stem cell maintenance are conserved in both meristems. For example, the gene WUSCHEL-RELATED HOMEOBOX5 (WOX5), which encodes a homeodomain transcription factor similar to WUS, non-cell-autonomously maintains stem cells in the RAM of Arabidopsis (Sarkar et al., 2007). Furthermore, overexpression of CLV3 results in inhibition of root elongation, and exogenous application of CLV3 peptides promotes consumption of the meristems in both the root and the shoot (Hobe et al., 2003; Fiers et al., 2005; Ito et al., 2006). CLE19 and CLE40 have the CLE domains similar to that of CLV3. Overexpression of these proteins, or in vitro application of their CLE peptides, induces defects similar to those induced by CLV3 or its CLE peptide (Casamitjana-Martinez et al., 2003; Hobe et al., 2003; Fiers et al., 2005).

Grasses such as rice (Oryza sativa) and maize (Zea mays) are considered model plants in the monocots, because genetic approaches are available and much information has been accumulated by genomic studies. Plant architecture and the morphologies of lateral organs are highly diversified in eudicots and monocots (Bommert et al., 2005b). It is of great interest to know whether developmental mechanisms are conserved in distantly related plants in the angiosperms or whether they have diversified during evolution. In flower organ specification, the ABC model, which has been proposed based on studies in eudicots such as Arabidopsis and Antirrhinum majus, is applicable to rice and maize (Bommert et al., 2005b; Kater et al., 2006; Yamaguchi and Hirano, 2006). However, two C-class MADS box genes, which were duplicated before the divergence of grasses, have functionally diversified to regulate meristem determinacy and stamen development in rice, whereas both functions are regulated by a single gene, AG, in Arabidopsis (Yanofsky et al., 1990; Yamaguchi et al., 2006). In addition, carpel specification is principally regulated by the YABBY gene DROOPING LEAF in rice, whereas C-class MADS box genes have a critical role in carpel specification in eudicots (Yanofsky et al., 1990; Yamaguchi et al., 2004). These studies suggest that, although the basic genetic networks that regulate floral organ specification are conserved in both Arabidopsis and rice, the functions of the individual genes have diversified in some cases during evolution.

In the genetic regulation of meristem maintenance, genes similar to those in Arabidopsis are involved in restricting the stem cell population in grasses. The FLORAL ORGAN NUMBER1 (FON1) gene in rice and the thick tassel dwarf1 gene in maize encode receptor kinases closely related to Arabidopsis CLV1, and the maize fasciated ear2 gene encodes a leucine-rich repeat (LRR) protein similar to CLV2 (Taguchi-Shiobara et al., 2001; Suzaki et al., 2004; Bommert et al., 2005a). Loss of function of these genes results in enlargement of the reproductive meristems, causing an increase in floral organ number in both rice and maize and fasciation of the inflorescences in maize. Rice FON2 encodes a CLE protein related to CLV3 (Suzaki et al., 2006). As in the fon1 mutant, the FM is enlarged in the fon2 mutant, resulting in an increase in floral organ number (Nagasawa et al., 1996; Suzaki et al., 2006). Although a mutant showing phenotypes similar to fon1 and fon2 was originally reported as fon4 (Chu et al., 2006), subsequent comparison of the isolated genes revealed that fon4 is an allele of the FON2 locus (Nagasawa et al., 1996; Suzaki et al., 2006). Overexpression of FON2 results in a decrease in the number of flowers and floral organs, suggesting a reduction in the size of the inflorescence meristem (IM) and the FM (Suzaki et al., 2006). Because no effects of FON2 overexpression are observed in fon1, FON2 is likely to act as a putative ligand for a receptor complex composed of FON1 in rice. These studies indicate that a pathway similar to the CLV signaling pathway in Arabidopsis is conserved in both rice and maize and negatively regulates stem cell maintenance in the grasses.

Unlike the clv mutants in Arabidopsis, even the severe fon1 and fon2 mutants show no abnormalities in the vegetative phase in rice (Nagasawa et al., 1996; Suzaki et al., 2004, 2006). Furthermore, overexpression of FON2 causes no phenotypic alteration in the vegetative phase (Suzaki et al., 2006). These results suggest that a signaling molecule other than FON2 may function in stem cell maintenance in the vegetative SAM in rice. Here, we show that FON2-LIKE CLE PROTEIN1 (FCP1), also known as Os CLE402 (Kinoshita et al., 2007), is expressed predominantly in the SAM, FM, and RAM and that constitutive expression of FCP1 and exogenous application of the FCP1 CLE peptide consume the SAM and the RAM, respectively, in the vegetative phase. These results suggest that FCP1 might be involved in the maintenance of the SAM and RAM. We also found that FON1 is not required for these FCP1 functions. This FCP1 function contrasts with the FON1-dependent function of FON2, which is responsible for maintaining reproductive meristems such as the FM and IM (Suzaki et al., 2006). Thus, FON2 and FCP1 may have functionally diversified to regulate the different types of meristems. We also report the identification of a key amino acid residue that differentiates the action of FCP1 and FON2.

RESULTS

FCP1 Is Expressed in the Meristems in the Shoot and Root Apex

To identify a signaling molecule responsible for meristem maintenance in the vegetative phase in rice, we initially focused on FCP1, which is closely related to FON2 and Arabidopsis CLV3 and has been temporarily called Os CLE402 (Kinoshita et al., 2007). The CLE domain of FCP1 is highly similar to that of FON2 (Figure 1A). In addition, the FCP1 gene has two introns, as does FON2 (Figure 1B), whereas many other rice CLE genes have no introns. We also focused on FCP2, also known as Os CLE50 (Chu et al., 2006), the CLE domain of which differed from that of FCP1 by only one amino acid (Figure 1A). RT-PCR analysis showed that FCP1 transcripts were expressed at high levels in all tissues that contained meristems but were expressed at much more lower levels in the leaf blade (Figure 1C). FCP2 showed a similar expression pattern, except in the inflorescence at the later stage, when the FM had been consumed by floral organs (Figure 1C).

Figure 1.

Structural Characteristics of FCP1 and Expression Patterns of FCP1 and FCP2.

(A) Alignment of amino acids in the putative active CLE peptide domain of related CLE proteins. Amino acid residues that differ from those in FCP1 are indicated in red.

(B) Schematic representation of FCP1 and FON2. Arrowheads indicate the positions of the introns. CLE, CLE domain; SP, signal peptide.

(C) RT-PCR–based expression analysis of FCP1 and FCP2. Similar results were obtained from two biological replicates. Lane 1, shoot apex; lane 2, leaf blade; lane 3, inflorescence at the stage of floral organ differentiation (3 to 8 mm in length); lane 4, inflorescence at the stage of floral organ development, including meiosis (3 to 5 cm in length); lane 5, root. Rice ACTIN1 was analyzed as a control.

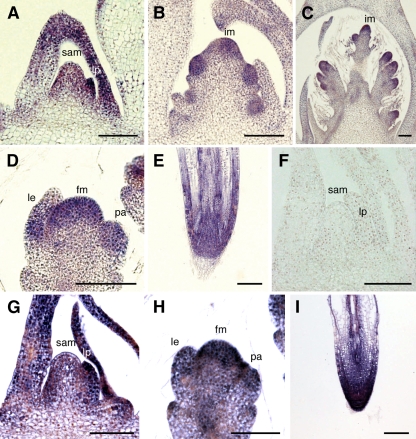

Next, we examined the spatial and temporal patterns of FCP1 expression by in situ hybridization. FCP1 was expressed in the SAM in the vegetative phase and in the IM and FM in the reproductive phase (Figures 2A to 2D). FCP1 transcripts were distributed throughout the meristem. In addition to the meristems, FCP1 transcripts were detected in the primordia of lateral organs, such as the leaf and the floral organs (Figures 2A and 2D). FCP1 was also expressed in the root tip, including the RAM (Figure 2E). Similarly, FCP2 was expressed in the SAM and the FM (Figures 2G and 2H) and in the root tip, including the RAM (Figure 2I). The spatial distribution of the FCP2 transcript was very similar to that of FCP1. Together with the high sequence similarity between the CLE domains of FCP1 and FCP2, these results suggest that FCP1 and FCP2 are functionally redundant.

Figure 2.

In Situ Localization of FCP1 and FCP2.

(A) In situ localization of FCP1 transcripts in the vegetative SAM.

(B) and (C) In situ localization of FCP1 transcripts in the IM.

(D) In situ localization of FCP1 transcripts in the FM.

(E) In situ localization of FCP1 transcripts in the root tip.

(F) In situ analysis using a sense probe of FCP1 in the SAM as a negative control.

(G) In situ localization of FCP2 transcripts in the vegetative SAM.

(H) In situ localization of FCP2 transcripts in the FM.

(I) In situ localization of FCP2 transcripts in the root tip.

An antisense probe was used except for (F). le, lemma; lp, leaf primordia; pa, palea. Bars = 100 μm.

To examine loss-of-function phenotypes of FCP1, we tried to repress the endogenous gene activity of FCP1 by RNA interference (RNAi). Although FCP1 transcripts were efficiently reduced by RNAi (see Supplemental Figure 1A online), the seedling phenotypes and meristem sizes of the RNAi lines were indistinguishable from those of the wild type (see Supplemental Figures 1B to 1D online). Then, we tried to regenerate transgenic plants carrying an RNAi construct that represses both FCP1 and FCP2. In spite of our efforts, calli carrying this construct failed to regenerate shoots, suggesting that the downregulation of both FCP1 and FCP2 may cause serious defects in cell differentiation.

Constitutive Expression of FCP1 Promotes Consumption of the Meristem in the Shoot

To elucidate the function of FCP1, we produced transgenic rice that constitutively expressed FCP1 under the control of the rice actin promoter. Although shoots were formed from calli in the regeneration medium, Actin:FCP1 plants ceased growth prematurely after forming two to three leaves and died at the subsequent seedling stage (Figures 3A and 3B). Close examination of the shoot apex showed that the meristem was dome-shaped, and the leaf primordia initiated in alternate phyllotaxy in the wild type (Figure 3E). In Actin:FCP1 plants, by contrast, the SAM was evidently reduced in size and flattened rather than dome-shaped, and no new leaf primordia were observed (Figure 3F). These phenotypes are similar to those observed in transgenic Arabidopsis overexpressing CLV3 (Brand et al., 2000; Müller et al., 2006). Therefore, it is probable that the SAM failed to maintain its stem cell population in the Actin:FCP1 plants. No root was formed in the Actin:FCP1 plants, suggesting that initiation of adventitious root was prevented (Figures 3A and 3B).

Figure 3.

Effects of Overexpression of FCP1, FON2, and Modified FON2.

(A), (B), and (E) to (K) Transformed wild-type plants.

(C) and (D) Transformed fon1-5 plants.

(A) to (D) Shoot phenotypes of plants transformed with Actin:FCP1.

(E) Vegetative SAM of a plant transformed with empty vector.

(F) Vegetative SAM of a plant transformed with Actin:FCP1.

(G) Shoot phenotype of a plant transformed with empty vector.

(H) Shoot phenotype of a plant transformed with Actin:FON2.

(I) Shoot of a plant expressing FON2/mCLE-2 showing a seedling-lethal phenotype.

(J) Shoot of a plant expressing FON2/mCLE-2 showing a seedling-survival phenotype.

(K) Shoot of a plant expressing FON2/mCLE-2-5-10 showing a seedling-lethal phenotype.

(L) Effects of amino acid substitutions in the modified FON2 peptide on the survival rate of transgenic plants. Numerals in the name of the construct indicate the positions of the substituted amino acid residues in the CLE domain, which are shown at right (see Supplemental Figure 2A online).

lp, leaf primordia. Bars = 5 mm in (A) to (D) and (G) to (K) and 100 μm in (E) and (F).

Next, we overexpressed FCP1 in the fon1-5 null mutant, in which FON1 has a nonsense mutation in the position corresponding to the second repeat of the LRR domain. The phenotypes resulting from Actin:FCP1 expression in fon1-5 were highly similar to those resulting from Actin:FCP1 expression in the wild type (Figures 3C and 3D), suggesting that FON1 is not required for FCP1 action. When FON2 was introduced into the wild type, the resulting Actin:FON2 plants showed no abnormalities in the shoot or root in the vegetative phase and were indistinguishable from transgenic rice transformed with vector only (Figures 3G and 3H). Taking these results together, it is probable that FCP1, unlike FON2, may be involved in stem cell maintenance in the vegetative SAM.

Identification of an Amino Acid That Differentiates between FCP1 and FON2 Function

Although FCP1 and FON2 are closely related, the vegetative meristems were reduced in size only when FCP1, and not FON2, was constitutively expressed. Therefore, we tried to identify the amino acids that differentiate between the action of FCP1 and FON2. There are three amino acid differences in the putative active CLE peptides of FCP1 and FON2 (Figure 1A). We introduced amino acid substitution(s) in the CLE domain of FON2 (see Supplemental Figure 2A online) and produced transgenic rice that constitutively expressed the modified FON2 proteins. The resulting transgenic rice showed two typical phenotypes, a normal and a seedling-lethal phenotype. These two distinctive phenotypes, produced by overexpressing FON2/mCLE-2, are shown in Figures 3I and 3J. The seedling-lethal phenotypes of transgenic rice carrying various modified FON2 constructs were similar to those of Actin:FCP1 plants (Figures 3A, 3B, and 3I to 3K).

The seedlings with normal phenotypes may have survived serious effects caused by the modified FON2 constructs. We evaluated the FCP1-like activity of the modified proteins by their effects on the survival rates of plants constitutively expressing the modified FON2 genes (Figure 3L). The CLE domain of FON2/mCLE-2-5-10 has the same amino acid sequence as that of FCP1, but elsewhere, FON2/mCLE-2-5-10 is identical in sequence to FON2. Transgenic rice expressing FON2/mCLE-2-5-10 showed a strongly reduced survival rate similar to that of plants expressing FCP1 (Figure 3L). This result suggests that amino acids in the CLE domain are responsible for FCP1 function and that the peptide in the modified CLE domain was processed into an active form from FON2/mCLE-2-5-10, as it is in the CLE domain from FCP1. Experiments with single amino acid substitutions revealed that the tenth amino acid, rather than the second or fifth, was most important for FCP1 function (Figure 3L). The importance of this amino acid was supported by a comparison of FON2/mCLE-2-10 (or FON2/mCLE-5-10) and FON2/mCLE-2-5. Importantly, the effect of FON2/mCLE-10 was comparable to that of FON2/mCLE-2-5-10. Taking these results together, we conclude that the tenth residue, Ile, discriminates FCP1 function from FON2 function, although the other two amino acids at the second and fifth positions have minor effects on this differentiation. These amino acids may be involved in specific interactions between FCP1 and its putative receptor.

In Vitro Application of the FCP1 CLE Peptide Inhibits Root Elongation

Actin:FCP1 plants failed to initiate roots, suggesting that FCP1 may function in meristem maintenance in the root. In Arabidopsis, exogenous application of synthetic CLE peptides in vitro induced consumption of the meristems in the shoot and root (Fiers et al., 2005; Ito et al., 2006; Kondo et al., 2006). To elucidate FCP1 function in root development in more detail, we first examined the effect of CLE peptides of FCP1 and FON2 on root elongation. An FCP1 CLE peptide strongly inhibited root elongation compared with a negative control peptide (FCP1-CLE [−R]) that lacked the first Arg (Figure 4A; see Supplemental Figure 2B online) (Kondo et al., 2006). By contrast, FON2 CLE had only a slight effect on root elongation. Experiments using modified FON2 CLE peptides indicated that the tenth residue, Ile, was most effective in inhibiting root elongation (Figure 4B; see Supplemental Figure 2B online). This result is consistent with the effect of modified FON2 on shoot phenotypes in transgenic analyses. Inhibition of root elongation by FCP1 CLE was also observed in fon1-5 (Figure 4C), confirming that FON1 is not required for FCP1 action. Shoot phenotypes were not affected by the CLE peptide of either FCP1 or FON2 under the conditions used here.

Figure 4.

Inhibitory Effects of in Vitro Application of CLE Peptides.

(A) Effects of FCP1 and FON2 CLE peptides on the elongation of wild-type roots.

(B) Effects of modified CLE peptides on the elongation of wild-type roots. Amino acid sequences in the CLE peptide used are shown in Supplemental Figure 2B online.

(C) Effects of FCP1 and FON2 CLE peptides on the elongation of fon1 roots.

(D) to (F) Phenotypes of roots mock-treated (D) or treated with 30 μM FCP1 (E) or FON2 (F) CLE peptide for 7 d.

(D′) and (E′) Magnified views of (D) and (E), respectively.

For (A) to (C), the length of the seminal root (n = 12) was measured at 7 d after peptide application. Bars = 100 μm.

Exogenous Application of the FCP1 CLE Peptide Disturbs Root Development by Misspecification of Cell Fate

Next, we examined the effect of the CLE peptide on root development. Root architecture was disturbed by exposure to FCP1 CLE for 7 d. Although the root tip inside the columella layer cells in the mock-treated root was round like that in normal wild-type roots (Figures 4D and 4D′), it became thinner and tapered after application of FCP1 CLE (Figures 4E and 4E′). The differentiated cell zone including root hairs was close to the tips (Figure 4E). These results suggest that the RAM fails to maintain meristematic activity.

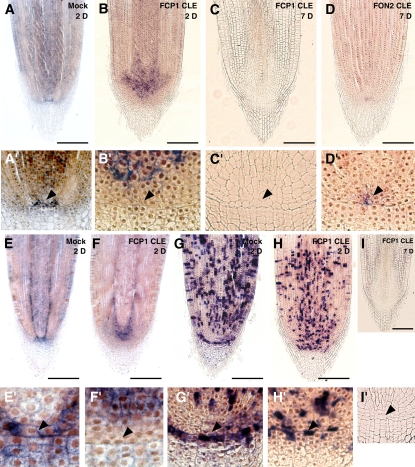

We then examined the in situ localization of markers of root development, such as QUIESCENT-CENTER-SPECIFIC HOMEOBOX (QHB), Os SCR, and HISTONE H4. QHB encodes a novel homeobox gene that is specifically expressed in the quiescent center (QC) of the rice RAM (Kamiya et al., 2003b) and is an ortholog of WOX5 in Arabidopsis (Sarkar et al., 2007). In situ localization analysis showed that QHB was expressed in a few cells in a putative QC region in the mock-treated root, as expected (Figures 5A and 5A′). By contrast, when the root was exposed to FCP1 CLE for 2 d, QHB expression was downregulated in the original region and its region of expression was greatly expanded upward (Figures 5B and 5B′). Furthermore, QHB expression was suppressed until 7 d after treatment (Figures 5C and 5C′).

Figure 5.

Spatial Expression Patterns of QHB, Os SCR, and HISTONE H4 in the RAM Treated with CLE Peptides.

(A) to (D) In situ localization of QHB transcripts in the RAM mock-treated or treated with the indicated CLE peptides.

(E) and (F) In situ localization of Os SCR transcripts in the RAM mock-treated (E) or treated with FCP1 CLE peptides (F).

(G) to (I) In situ localization of HISTONE H4 transcripts in the RAM mock-treated (G) or treated with FCP1 CLE peptides ([H] and [I]).

(A′) to (I′) Magnified views of (A) to (I), respectively.

Seedlings were treated with 30 μM peptide for 2 or 7 d. Arrowheads indicate the position of the QC region. Bars = 100 μm.

Os SCR is an ortholog of the Arabidopsis SCARECROW (SCR) gene that regulates radial patterning and QC specification in the root (Di Laurenzio et al., 1996; Kamiya et al., 2003a; Sabatini et al., 2003). As expected, Os SCR was expressed in the endodermal cell layer, the region surrounding the QC, and the QC itself in the mock-treated root (Figures 5E and 5E′). By contrast, expression patterns were disturbed after 2 d of exposure to FCP1 CLE; the region of expression of Os SCR was shifted upward and expanded to cells other than those of the endodermal layer (Figure 5F). Expression of Os SCR disappeared from the QC (Figure 5F′). The S-phase–specific maker HISTONE H4 was expressed in the meristematic zone in the mock-treated root (Figures 5G and 5G′); however, the number of cells expressing HISTONE H4 and its expression levels were reduced by 2 d of exposure to FCP1 CLE and were completely suppressed by 7 d of exposure (Figures 5H, 5H′, 5I, and 5I′). Notably, FCP1 CLE treatment induced the expression of HISTONE H4 in the QC (Figure 5H′), a region that did not show HISTONE H4 expression in the mock-treated root (Figure 5G′).

Thus, the spatial expression patterns of these markers suggest that cell fates in the RAM are misspecified by exogenous application of FCP1 CLE in vitro. The reduction in the number of cells expressing HISTONE H4 is consistent with the root phenotype that lacked a meristematic zone.

In contrast with FCP1 CLE, FON2 CLE had only a slight effect on the root phenotype (Figure 4F), and QHB was properly expressed in the QC even after 7 d of exposure to the FON2 CLE peptide (Figures 5D and 5D′). Taking these results together, it is likely that a signaling pathway involving FCP1, rather than FON2, is involved in stem cell maintenance in the RAM.

DISCUSSION

FCP1 Appears to Be Involved in Stem Cell Maintenance in the SAM in the Vegetative Phase

We have shown here that FCP1 may be involved in the maintenance of the SAM during the vegetative phase of development. FCP1 is expressed predominantly in the SAM, FM, and RAM, and constitutive expression of FCP1 induced consumption of the SAM in the vegetative phase. This FCP1 action was found in the null mutant fon1. Similarly, application of the FCP1 CLE peptide affected root development in the absence of FON1. Therefore, FCP1 may act through a putative receptor that is distinct from FON1. The tenth residue in the FCP1 CLE peptide, Ile, might be a main amino acid that discriminates the action of FCP1 from that of FON2. This conclusion was drawn from two independent experiments: the effects of overexpressing modified FON2 genes on shoot phenotypes in transgenic plants, and the effects of in vitro application of modified FON2 peptides on root elongation.

By contrast, constitutive expression of FON2 caused no abnormalities in the vegetative phenotypes. On the other hand, the fon2 mutation results in an enlargement of the FM and FON2 overexpression causes a reduction in the sizes of the FM and IM (Suzaki et al., 2006). Thus, FON2 is responsible for meristem maintenance in the reproductive phase but not in the vegetative phase. Taking these results together, there appears to be a differentiation of function between FCP1 and FON2, two CLE genes closely related to Arabidopsis CLV3, so that they regulate different types of the aerial meristems in rice.

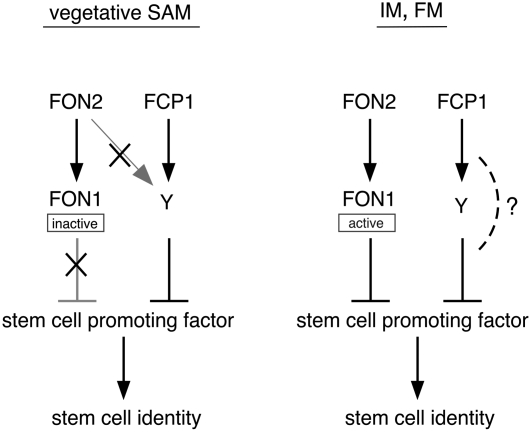

Previously, we proposed a model of meristem maintenance in rice based on the molecular genetic analysis of FON1 and FON2 (Suzaki et al., 2006). In that model, we proposed the existence of an alternative pathway to FON1–FON2 to explain the discrepancy between the effect of the fon2 mutation and that of FON2 overexpression. This alternative pathway is assumed to act redundantly to the FON pathway in the vegetative SAM and the IM. The results obtained here are consistent with the idea that FCP1 might be a signaling molecule in this alternative pathway (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Model of Meristem Maintenance in Rice.

This model proposes that rice has two CLV-like pathways that negatively regulate stem cell identity. FON2 and FCP1 may act as signaling molecules at their putative receptors, FON1 and Y (representing an unknown protein). The FON2–FON1 pathway is responsible for regulating the IM and FM, whereas the pathway including FCP1 may be involved in regulating the vegetative SAM. FON2 may not recognize the putative receptor Y, because no abnormalities in the vegetative SAM were induced by FON2 overexpression. Inactivity of FON1 in the vegetative SAM has been suggested by our previous work (Suzaki et al., 2006). The large Xs indicate that the gray pathway with this mark is not functional. The question mark indicates processes that are unclear at present and remain to be elucidated in the future. The stem cell–promoting factor corresponding to WUS in Arabidopsis has not been identified to date in rice.

Constitutive RNAi suppression of FCP1 led to no clear conclusion, possibly because of functional redundancy between the FCP1 and FCP2 genes. Furthermore, our attempts to produce transgenic plants expressing a constitutive RNAi construct designed to suppress both genes were not successful, because of unexpected serious defects in calli carrying the construct. To verify our inferences regarding the functions of these genes, loss-of-function analyses such as RNAi suppression using their own or inducible promoters may be required.

With regard to the in vitro application of the FON2 CLE peptide, there is an inconsistency between our results and those of Chu et al. (2006). Here, we show that exogenous application of FON2 peptides had no effect on the shoot phenotype. However, Chu et al. (2006) reported that in vitro application of the CLE peptide of FON4 (=FON2) results in termination of the SAM. (The mutations described as fon4 by Chu et al. [2006]have subsequently been shown to be in an allele of the FON2 locus [Suzaki et al., 2006].) This discrepancy may be due to indirect effects caused by the application of a high concentration of the CLE peptide in the experiment by Chu et al. (2006). In fact, application of FON2-CLE [−R], a putatively inactive form that lacks the first Arg essential for function of the CLE peptide (Ito et al., 2006), induced seedling-lethal phenotypes in both the wild type and the fon1 mutant when it was applied at a high concentration such as 50 μM (see Supplemental Figure 3 online). Therefore, careful interpretation should be given to the results of in vitro experiments performed at high concentrations.

FCP1 Seems to Be Involved in Meristem Maintenance in the Root

Constitutive expression of FCP1 inhibited the initiation of adventitious roots, and application of the FCP1 CLE peptide in vitro disturbed root development after germination. The resulting phenotypes, such as inhibition of root elongation and loss of the meristematic zone, are similar to those caused by overexpression of CLV3 and exogenous application of CLE peptides such as CLV3, CLE19, and CLE40 in Arabidopsis (Hobe et al., 2003; Fiers et al., 2005; Ito et al., 2006; Kondo et al., 2006). Levels of QHB and HISTONE H4 in the regions where they were expressed in mock-treated roots were first reduced and then completely inhibited by continued treatment with the FCP1 CLE peptide. Moreover, expression domains of QHB and Os SCR were expanded to a region proximal to the RAM, and HISTONE H4 expression was initiated in cells in the putative QC region that originally expressed QHB. These results suggest that treatment with the FCP1 CLE peptide causes cell fates in the RAM to be misspecified and the meristem ultimately to be consumed. Consumption of the meristem is also supported by the thinner and conical phenotype of the root tip. By contrast, normal expression of QHB after 7 d of exposure to the FON2 CLE peptide suggests that FON2 has a weak role in root development.

In Arabidopsis, WOX5, which is expressed in the QC, regulates stem cell identity in the RAM, similar to WUS in the organizing center of the SAM (Sarkar et al., 2007). CLV3 and related proteins seem to act as negative regulators to restrict the proliferation of stem cells not only in the SAM and but also in the RAM (Brand et al., 2000; Hobe et al., 2003; Fiers et al., 2005; Müller et al., 2006). In rice, it is likely that FCP1 may be involved in RAM maintenance, as discussed above. The WUS-type homeodomain transcription factor QHB, an ortholog of WOX5, is suggested to have a role in maintenance of the RAM in rice (Kamiya et al., 2003b). Taking these findings together, we consider that factors that regulate stem cell maintenance in the RAM might be conserved between Arabidopsis and rice.

Functional Conservation and Diversification of the CLE Genes Related to Rice FCP1 and Arabidopsis CLV3

Among the CLE genes in rice and Arabidopsis, only four—FON2, FCP1, CLV3, and CLE40—have introns and encode highly similar CLE domains, suggesting that these genes have evolved from a common ancestor and have acquired related functions (Fletcher et al., 1999; Hobe et al., 2003; Suzaki et al., 2006). Indeed, expression of CLE40 by the CLV3 promoter indicates that CLE40 can function in regulating maintenance in the SAM in place of CLV3 in Arabidopsis, although the low endogenous expression of CLE40 is insufficient to contribute to CLV signaling (Hobe et al., 2003). In rice, however, the functions of FON2 and FCP1 seem to have partially diversified, such that the contribution of each gene has been adapted to different types of aerial meristems (Figure 6). Thus, FCP1 may be involved in maintenance of the SAM in the vegetative phase, whereas FON2 may be required for maintenance of the IM and FM in the reproductive phase. In the root, FCP1, rather than FON2, may be predominantly involved in maintenance of the RAM. Thus, these four CLE genes may have partially conserved functions between rice and Arabidopsis, whereas functions of paralogous genes may have functionally diverged during the evolution of the two species. In rice, two C-class MADS box genes have functionally diversified to partially share the function of AG in Arabidopsis (Yamaguchi et al., 2006). Functional partition of FCP1 and FON2 in regulating meristem maintenance may be a similar consequence of the evolution of rice.

Unfortunately, we could not clarify whether FCP1 has a role in regulating the FM or IM, because RNAi suppression of FCP1 showed no phenotypic changes and overexpression of FCP1 induced a seedling-lethal phenotype. In our model (Figure 6), we propose that FON1 is inactive in the vegetative SAM, because no abnormalities in this phase were observed after FON2 overexpression (Suzaki et al., 2006). Given this assumption, we cannot rule out the possibility that FCP1 might recognize functional FON1 in the reproductive meristems. To test this possibility and/or to clarify whether FCP1 functions in these meristems, we should examine the effect of FCP1 on the FM and IM in fon1 using an inducible promoter to avoid seedling lethality caused by FCP1 overexpression. For further understanding of FCP1 function, its putative receptor needs to be identified. Furthermore, identification of the factors that promote stem cell identity and elucidation of the mechanisms involving cytokinin action may be required for a deeper understanding of both stem cell maintenance in the SAM and RAM in rice and the evolution of its mechanism in the angiosperms (Leibfried et al., 2005; Kurakawa et al., 2007).

METHODS

Plant Materials

The rice strains used in this study were Oryza sativa japonica; Taichung65 was used as a wild-type strain. To analyze the effect of the fon1 mutation, we used a newly identified null allele, fon1-5, which contains a nonsense mutation in the second repeat of the LRR domain.

Identification of FCP1 and FCP2

FCP1 was identified by searching the rice genomic sequence database by the BLAST program (Altschul et al., 1990) using the amino acid sequence of the FON2 CLE domain as a query. Then, FCP2 was identified using the FCP1 CLE domain as a query. We amplified cDNAs for FCP1 and FCP2 (see Supplemental Table 1 online for primers) from total RNA isolated from the shoot apex as described below. After sequencing of the RT-PCR products, we predicted the open reading frames for the two genes and the positions of introns for FCP1. FCP1 and FCP2 correspond to Os CLE402 and Os CLE50, respectively (Chu et al., 2006; Kinoshita et al., 2007).

RNA Isolation and RT-PCR Analysis

Total RNA was isolated from each plant tissue using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) and treated with DNase I (Invitrogen) to remove genomic DNA. The first strand of cDNA was synthesized from 1 μg of total RNA using SuperScript III RNaseH− reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen) and oligo(dT)20 primer. PCR was performed for 30 cycles at 98°C for 10 s, 58°C for 30 s, and 68°C for 30 s. PCR products were subjected to gel electrophoresis and detected by ethidium bromide staining.

In Situ Hybridization

The primers used for PCR amplifications are shown in Supplemental Table 1 online. To create the in situ hybridization probe for FCP1, a 463-bp fragment consisting of the entire coding region, the 5′ untranslated region (UTR; 38 bp), and the 3′ UTR (65 bp) was amplified by PCR. To create the probe for FCP2, a 636-bp fragment consisting of the entire coding region, the 5′ UTR (173 bp), and the 3′ UTR (88 bp) was amplified. The probe for QHB was created by PCR amplification of a 780-bp fragment consisting of the entire coding region, the 5′ UTR (72 bp), and the 3′ UTR (105 bp). The probe for Os SCR was created by amplification of a 740-bp fragment at the 3′ end of the coding region. The fragments were inserted into a T-vector by TA cloning (Novagen). The full-length rice HISTONE H4 cDNA clone was kindly provided by M. Matsuoka (Nagoya University). To generate antisense or sense probe, RNAs were transcribed with T7 or SP6 RNA polymerase from the above constructs as templates and were labeled with digoxigenin (Roche). The synthesized RNAs were partially hydrolyzed with alkaline solution (60 mM Na2CO3 and 40 mM NaHCO3, pH 10.2) at 60°C for 60 min. Preparation of sections and in situ hybridization were performed as described previously (Suzaki et al., 2004). Signals were observed with a light microscope (BX-50; Olympus).

Transformation of Rice

For constitutive expression of FCP1, the FCP1 cDNA was inserted into a XbaI site of the binary vector pAct-nos/Hm2, which contains a cassette of the rice actin promoter and the nos terminator (Sentoku et al., 2000). For constitutive expression of FON2, we used a previously described construct (Suzaki et al., 2006). To generate constructs of Actin:FON2 with a modified CLE domain, point mutations were introduced in the CLE domain of FON2 using the primers (see Supplemental Table 1 online) and the QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene). The modified FON2 cDNA was inserted into pAct-nos/Hm2.

For RNA silencing of FCP1 (FCP1-RNAi), part of the FCP1 cDNA containing almost the entire coding region was amplified using the primers listed in Supplemental Table 1 online and was cloned into the pENTR/D-TOPO vector (Invitrogen). The resulting vector was named pENTR-FCP1. To make RNAi constructs, a modified PANDA vector (PANDA-EG1) was used. The original PANDA vector was designed to insert simultaneously two copies of a DNA fragment in an inverted orientation by the LR recombination reaction (Miki and Shimamoto, 2004). In PANDA-EG1, the maize (Zea mays) ubiquitin1 promoter that was present in the original vector had been replaced by the rice actin promoter. To make FCP1-RNAi, the FCP1 cDNAs in pENTR-FCP1 were inserted in an inverted orientation into PANDA-EG1 by the LR recombination reaction (see Supplemental Figure 4A online).

To create an RNAi plasmid (FCP1:FCP2-RNAi) that would suppress the expression of both FCP1 and FCP2, part of the FCP2 cDNA containing almost the entire coding region was amplified using primers containing NotI sites (see Supplemental Table 1 online) and was cloned into the NotI site of pENTR-FCP1. A tandem sequence of the FCP1 and FCP2 cDNA was inserted in an inverted orientation into PANDA-EG1 by the LR recombination reaction (see Supplemental Figure 4B online).

The recombinant plasmids were introduced into Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain EHA101 and were transformed into rice as described previously (Hiei et al., 1994).

Histological Analysis

For observation of longitudinal sections of the shoot apex, samples were embedded in Technovit 7100 resin (Kulzer). Microtome sections (5 μm thick) were stained with 0.05% toluidine blue-O and observed with a light microscope (BX-50; Olympus). For observation of Nomarski images, the shoot apex and root tips were fixed with 4% (w/v) paraformaldehyde and 0.25% glutaraldehyde in 50 mM phosphate buffer for ∼16 h at 4°C and dehydrated in a graded ethanol series. After clearing in benzyl-benzoate-four-and-a-half fluid, the specimens were observed with a microscope equipped with Nomarski differential interference contrast optics.

Peptide Treatment in Vitro

CLE peptides were synthesized and purified to at least 95% using HPLC by Takara. Rice seeds were sterilized after husking and transferred into liquid Murashige and Skoog medium (pH 5.8) containing different concentrations of the peptides. To avoid loss of activity of the peptides, a high concentration of peptide solution (×1000) was carefully added to the sterilized medium after cooling to room temperature. Twelve seeds were treated with 10 mL of the medium containing peptide solution in a 100-mL conical flask with continuous shaking (100 rotations/min) at 28°C under 16-h-light/8-h-dark cycles.

Accession Numbers

Sequence data from this article can be found in the GenBank/EMBL/DDBJ data libraries under accession numbers AB354584 (FCP1), AB354585 (FCP2), and AB245090 (FON2).

Supplemental Data

The following materials are available in the online version of this article.

Supplemental Figure 1. Suppression of FCP1 Expression by RNAi.

Supplemental Figure 2. Amino Acid Sequences Corresponding to Putative Active Molecules in Rice CLE Proteins and Their Derivatives.

Supplemental Figure 3. Application of the FON2-CLE [−R] Peptide at a High Concentration Induces Seedling-Lethal Phenotypes.

Supplemental Figure 4. Constructs for RNAi of FCP1 (A) and of Both FCP1 and FCP2 (B).

Supplemental Table 1. Primers Used in This Work.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank T. Toriba and K. Ohsawa for technical assistance. This research was supported by the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry, and Fisheries of Japan (Rice Genome Project Grant IP-1005) and by the Program of Basic Research Activities for Innovative Biosciences.

The author responsible for distribution of materials integral to the findings presented in this article in accordance with the policy described in the Instructions for Authors (www.plantcell.org) is: Hiro-Yuki Hirano (hyhirano@biol.s.u-tokyo.ac.jp).

Online version contains Web-only data.

Open Access articles can be viewed online without a subscription.

References

- Altschul, S.F., Gish, W., Miller, W., Myers, E.W., and Lipman, D.J. (1990). Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215 403–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bommert, P., Lunde, C., Nardmann, J., Vollbrecht, E., Running, M., Jackson, D., Hake, S., and Werr, W. (2005. a). thick tassel dwarf1 encodes a putative maize ortholog of the Arabidopsis CLAVATA1 leucine-rich repeat receptor-like kinase. Development 132 1235–1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bommert, P., Satoh-Nagasawa, N., Jackson, D., and Hirano, H.-Y. (2005. b). Genetics and evolution of inflorescence and flower development in grasses. Plant Cell Physiol. 46 69–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brand, U., Fletcher, J.C., Hobe, M., Meyerowitz, E.M., and Simon, R. (2000). Dependence of stem cell fate in Arabidopsis on a feedback loop regulated by CLV3 activity. Science 289 617–619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casamitjana-Martinez, E., Hofhuis, H.F., Xu, J., Liu, C.-M., Heidstra, R., and Scheres, B. (2003). Root-specific CLE19 overexpression and the sol1/2 suppressors implicate a CLV-like pathway in the control of Arabidopsis root meristem maintenance. Curr. Biol. 13 1435–1441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu, H., Qian, Q., Liang, W., Yin, C., Tan, H., Yao, X., Yuan, Z., Yang, J., Huang, H., Luo, D., Ma, H., and Zhang, D. (2006). The FLORAL ORGAN NUMBER4 gene encoding a putative ortholog of Arabidopsis CLAVATA3 regulates apical meristem size in rice. Plant Physiol. 142 1039–1052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark, S.E., Running, M.P., and Meyerowitz, E.M. (1993). CLAVATA1, a regulator of meristem and flower development in Arabidopsis. Development 119 397–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark, S.E., Running, M.P., and Meyerowitz, E.M. (1995). CLAVATA3 is a specific regulator of shoot and floral meristem development affecting the same processes as CLAVATA1. Development 121 2057–2067. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, S.E., Williams, R.W., and Meyerowitz, E.M. (1997). The CLAVATA1 gene encodes a putative receptor kinase that controls shoot and floral meristem size in Arabidopsis. Cell 89 575–585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di-Laurenzio, L., Wysocka-Diller, J., Malamy, J.E., Pysh, L., Helariutta, Y., Freshour, G., Hahn, M.G., Feldmann, K.A., and Benfey, P.N. (1996). The SCARECROW gene regulates an asymmetric cell division that is essential for generating the radial organization of the Arabidopsis root. Cell 86 423–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiers, M., Golemiec, E., Xu, J., van der Geest, L., Heidstra, R., Stiekema, W., and Liu, C.-M. (2005). The 14-amino acid CLV3, CLE19, and CLE40 peptides trigger consumption of the root meristem in Arabidopsis through a CLAVATA2-dependent pathway. Plant Cell 17 2542–2553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher, J.C., Brand, U., Running, M.P., Simon, R., and Meyerowitz, E.M. (1999). Signaling of cell fate decisions by CLAVATA3 in Arabidopsis shoot meristems. Science 283 1911–1914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiei, Y., Ohta, S., Komari, T., and Kumashiro, T. (1994). Efficient transformation of rice (Oryza sativa L.) mediated by Agrobacterium and sequence analysis of the boundaries of the T-DNA. Plant J. 6 271–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobe, M., Müller, R., Grünewald, M., Brand, U., and Simon, R. (2003). Loss of CLE40, a protein functionally equivalent to the stem cell restricting signal CLV3, enhances root waving in Arabidopsis. Dev. Genes Evol. 213 371–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito, Y., Nakanomyo, I., Motose, H., Iwamoto, K., Sawa, S., Dohmae, N., and Fukuda, H. (2006). Dodeca-CLE peptides as suppressors of plant stem cell differentiation. Science 313 842–845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong, S., Trotochaud, A.E., and Clark, S.E. (1999). The Arabidopsis CLAVATA2 gene encodes a receptor-like protein required for the stability of the CLAVATA1 receptor-like kinase. Plant Cell 11 1925–1934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamiya, N., Itoh, J.I., Morikami, A., Nagato, Y., and Matsuoka, M. (2003. a). The SCARECROW gene's role in asymmetric cell divisions in rice plants. Plant J. 36 45–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamiya, N., Nagasaki, H., Morikami, A., Sato, Y., and Matsuoka, M. (2003. b). Isolation and characterization of a rice WUSCHEL-type homeobox gene that is specifically expressed in the central cells of a quiescent center in the root apical meristem. Plant J. 35 429–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kater, M.M., Dreni, L., and Colombo, L. (2006). Functional conservation of MADS-box factors controlling floral organ identity in rice and Arabidopsis. J. Exp. Bot. 57 3433–3444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinoshita, A., Nakamura, Y., Sasaki, E., Kyozuka, J., Fukuda, H., and Sawa, S. (2007). Gain-of-function phenotypes of chemically synthetic CLAVATA3/ESR-related (CLE) peptides in Arabidopsis thaliana and Oryza sativa. Plant Cell Physiol. 48 1821–1825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondo, T., Sawa, S., Kinoshita, A., Mizuno, S., Kakimoto, T., Fukuda, H., and Sakagami, Y. (2006). A plant peptide encoded by CLV3 identified by in situ MALDI-TOF MS analysis. Science 313 845–848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurakawa, T., Ueda, N., Maekawa, M., Kobayashi, K., Kojima, M., Nagato, Y., Sakakibara, H., and Kyozuka, J. (2007). Direct control of shoot meristem activity by a cytokinin-activating enzyme. Nature 445 652–655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leibfried, A., To, J.P.C., Busch, W., Stehling, S., Kehle, A., Demar, M., Kieber, J.J., and Lohmann, J.U. (2005). WUSCHEL controls meristem function by direct regulation of cytokinin-inducible response regulators. Nature 438 1172–1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer, K.F.X., Schoof, H., Haecker, A., Lenhard, M., Jürgens, G., and Laux, T. (1998). Role of WUSCHEL in regulating stem cell fate in the Arabidopsis shoot meristem. Cell 95 805–815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miki, D., and Shimamoto, K. (2004). Simple RNAi vectors for stable and transient suppression of gene function in rice. Plant Cell Physiol. 45 490–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller, R., Bleckmann, A., and Simon, R. (2008). The receptor kinase CORYNE of Arabidopsis transmits the stem cell-limiting signal CLAVATA3 independently of CLAVATA1. Plant Cell 20 934–946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller, R., Borghi, L., Kwiatkowska, D., Laufs, P., and Simon, R. (2006). Dynamic and compensatory responses of Arabidopsis shoot and floral meristems to CLV3 signaling. Plant Cell 18 1188–1198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagasawa, N., Miyoshi, M., Kitano, H., Satoh, H., and Nagato, Y. (1996). Mutations associated with floral organ number in rice. Planta 198 627–633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa, M., Shinohara, H., Sakagami, Y., and Matsubayashi, Y. (2008). Arabidopsis CLV3 peptide directly binds CLV1 ectodomain. Science 319 294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy, G.V., and Meyerowitz, E.M. (2005). Stem-cell homeostasis and growth dynamics can be uncoupled in the Arabidopsis shoot apex. Science 310 663–667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabatini, S., Heidstra, R., Wildwater, M., and Scheres, B. (2003). SCARECROW is involved in positioning the stem cell niche in the Arabidopsis root meristem. Genes Dev. 17 354–358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar, A.K., Luijten, M., Miyashima, S., Lenhard, M., Hashimoto, T., Nakajima, K., Scheres, B., Heidstra, R., and Laux, T. (2007). Conserved factors regulate signalling in Arabidopsis thaliana shoot and root stem cell organizers. Nature 446 811–814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheres, B. (2007). Stem-cell niches: Nursery rhymes across kingdoms. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 8 345–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoof, H., Lenhard, M., Haecker, A., Mayer, K.F.X., Jürgens, G., and Laux, T. (2000). The stem cell population of Arabidopsis shoot meristems is maintained by a regulatory loop between the CLAVATA and WUSCHEL genes. Cell 100 635–644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sentoku, N., Sato, Y., and Matsuoka, M. (2000). Overexpression of rice OSH genes induces ectopic shoots on leaf sheaths of transgenic rice plants. Dev. Biol. 220 358–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stahl, Y., and Simon, R. (2005). Plant stem cell niches. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 49 479–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzaki, T., Sato, M., Ashikari, M., Miyoshi, M., Nagato, Y., and Hirano, H.-Y. (2004). The gene FLORAL ORGAN NUMBER1 regulates floral meristem size in rice and encodes a leucine-rich repeat receptor kinase orthologous to Arabidopsis CLAVATA1. Development 131 5649–5657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzaki, T., Toriba, T., Fujimoto, M., Tsutsumi, N., Kitano, H., and Hirano, H.-Y. (2006). Conservation and diversification of meristem maintenance mechanism in Oryza sativa: Function of the FLORAL ORGAN NUMBER2 gene. Plant Cell Physiol. 47 1591–1602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taguchi-Shiobara, F., Yuan, Z., Hake, S., and Jackson, D. (2001). The fasciated ear2 gene encodes a leucine-rich repeat receptor-like protein that regulates shoot meristem proliferation in maize. Genes Dev. 15 2755–2766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi, T., and Hirano, H.Y. (2006). Function and diversification of MADS-box genes in rice. ScientificWorldJournal 6 1923–1932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi, T., Lee, Y.D., Miyao, A., Hirochika, H., An, G., and Hirano, H.-Y. (2006). Functional diversification of the two C-class genes, OSMADS3 and OSMADS58, in Oryza sativa. Plant Cell 18 15–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi, T., Nagasawa, N., Kawasaki, S., Matsuoka, M., Nagato, Y., and Hirano, H.-Y. (2004). The YABBY gene DROOPING LEAF regulates carpel specification and midrib development in Oryza sativa. Plant Cell 16 500–509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanofsky, M.F., Ma, H., Bowman, J.L., Drews, G.N., Feldmann, K.A., and Meyerowitz, E.M. (1990). The protein encoded by the Arabidopsis homeotic gene agamous resembles transcription factors. Nature 346 35–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.