Abstract

The deficits in Alzheimer disease (AD) stem at least partly from neurotoxic β-amyloid peptides generated from the amyloid precursor protein (APP). APP may also be cleaved intracellularly at Asp664 to yield a second neurotoxic peptide, C31. Previously, we showed that cleavage of APP at the C-terminus is required for the impairments seen in APP transgenic mice, by comparing elements of the disease in animals modeling AD, with (platelet-derived growth factor B-chain promoter-driven APP transgenic mice; PDAPP) versus without (PDAPP D664A) a functional Asp664 caspase cleavage site. However, the signaling mechanism(s) by which Asp664 contributes to these deficits remains to be elucidated. In this study, we identify a kinase protein, recently shown to bind APP at the C-terminus and to contribute to AD, whose activity is modified in PDAPP mice, but normalized in PDAPP D664A mice. Specifically, we observed a significant increase in nuclear p21-activated kinase (isoforms 1, 2, and or 3; PAK-1/2/3) activation in hippocampus of 3 month old PDAPP mice compared with non-transgenic littermates, an effect completely prevented in PDAPP D664A mice. In contrast, 13 month old PDAPP mice displayed a significant decrease in PAK-1/2/3 activity, which was once again absent in PDAPP D664A mice. Similarly, in hippocampus of early and severe AD subjects, there was a progressive and subcellular-specific reduction in active PAK-1/2/3 compared with normal controls. Interestingly, total PAK-1/2/3 protein was increased in early AD subjects, but declined in moderate AD and declined further, to significantly below that of control levels, in severe AD. These findings are compatible with previous suggestions that PAK may be involved in the pathophysiology of AD, and demonstrate that both early activation and late inactivation in the murine AD model require the cleavage of APP at Asp664.

Keywords: C31, familial Alzheimer disease, intracellular domain, signal transduction, transgenic mouse model, β-amyloid precursor protein

The cognitive deficits characteristic of Alzheimer disease (AD) are attributed to the loss of synapses, and ultimately neurons (Stephan et al. 2001). Toxic proteins that accrue in the AD brain are believed to precipitate this demise through diagnostic lesions such as senile plaques and neurofibrillary tangles (Hyman and Tanzi 1992). The main proteinaceous constituent of plaques is β-amyloid (Aβ), a peptide derived by cleavage of the amyloid precursor protein (APP) (Glabe 2001). The amyloid hypothesis maintains that extracellular Aβ accumulation instigates a series of events that culminates in a collection of impairments associated with AD (Lee et al. 2004). For example, APP transgenic mice with elevated brain levels of Aβ exhibit synapse loss, behavioral abnormalities, and synaptic transmission deficits well before plaque formation (Hsia et al. 1999; Mucke et al. 2000).

Despite the wealth of evidence indicating that AD-related defects are consequences of Aβ, little is known about the mechanistic pathways leading downstream of Aβ to damage. Several groups have previously demonstrated in cell culture the significance of the C-terminus of APP, including evidence that certain cleavage products from that region influence gene expression and cell survival (Cao and Sudhof 2001; Galvan et al. 2002; Kim et al. 2003). In particular, APP contains an intracytoplasmic caspase cleavage site - VEVD at codons 661-664 - and cleavage at Asp664 liberates a cytotoxic C-terminal peptide, C31 (Lu et al. 2000, 2003). Several findings suggest the functionality of this cleavage site in the genesis of AD pathology. For example, Aβ treatment enhances cleavage at Asp664 and an Asp664 mutation attenuates Aβ-induced cell death (Lu et al. 2000, 2003). Furthermore, cleavage of APP at Asp664 is amplified in brains of AD subjects (Zhao et al. 2003) and APP transgenic mice (Galvan et al. 2006). In support of these findings, our group recently showed that introducing an Asp664 mutation [Asp → Ala; aspartate to alanine mutation at position 664 of APP (D664A)] prevents the neuropathological and behavioral deficits in an Alzheimer transgenic model, platelet-derived growth factor B-chain promoter-driven APP transgenic mice (PDAPP) mice (Galvan et al. 2006).

However, the mechanism(s) by which this neuroprotective effect is achieved, and in particular the resulting effect(s) on APP-mediated signal transduction, have not been explored. Based on data regarding (i) the pathophysiological actions of APP and those of its proteolytic products (Chang and Suh 2005; Reddy 2006), (ii) the knowledge that APP is a transmembrane protein similar to a signaling receptor (Okamoto et al. 1995), and (iii) identification of binding proteins at the C-terminus of APP (Chang et al. 2003; Russo et al. 2005), Aβ production and subsequent intracytoplasmic cleavage of APP may initiate a signaling cascade that is dependent on the Asp664 cleavage site and underlies the Aβ-directed neurodegeneration.

Although relatively little is known about signaling pathways activated by the APP cytoplasmic domain, the p21-activated kinase (PAK) family (subdivided into group I that includes isoforms PAK-1, PAK-2, and PAK-3 and group II that includes PAK-4, PAK-5, and PAK-6) has recently been identified in the pathogenesis of AD. In neuron cultures, PAK-3 interacts within the C100 region of APP and mediates C31-induced apoptosis (McPhie et al. 2003). In addition, PAK-1 and PAK-3 loss has been suggested to contribute to the dendritic spine defects and cognitive deficits seen in brains of AD subjects and APP Swedish mice (Zhao et al. 2006). Furthermore, PAK-5 binds Par-1 and suppresses τ hyperphosphorylation in early Alzheimer neurodegeneration (Matenia et al. 2005).

The availability of Alzheimer model transgenic mice that are matched for their APP expression, Aβ production, and plaque number, but completely discordant with respect to AD-related sequelae such as synapse loss, electrophysiological abnormalities, and behavioral deficits (Galvan et al. 2006; Saganich et al. 2006), allows for the identification of underlying candidate signaling mechanisms. Therefore, in the present study, PAK-1/2/3 (isoforms 1, 2, and or 3) was examined in two transgenic mouse lines: (i) PDAPP mice and (ii) mice genetically matched except for a mutation at amino acid 664 in the intracytoplasmic domain of APP. We assessed the effect of the D664A mutation on PAK-1/2/3 activation and expression in PDAPP mice that model AD.

Materials and methods

Antibodies

The following antibodies were used for either immunohistochemistry (IHC) or western blotting (WB): rabbit polyclonal phosphorylation-specific PAK-1/2/3 (Ser141) (44-940G; IHC) and mouse monoclonal glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH; ZG003; WB) were obtained from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA, USA), rabbit polyclonal phosphorylation-specific PAK-1 (Thr423)/PAK-2 (Thr402) (2601; WB) and total PAK-1/2/3 (2604; WB) was acquired from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA, USA), and mouse monoclonal protein disulfide isomerase (PDI) (ab2792; IHC) was procured from Abcam (Cambridge, MA, USA). Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated donkey anti-mouse (WB) and anti-rabbit (WB) were from Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories (West Grove, PA, USA). Alexa Fluor488 donkey anti-rabbit (A-21206; IHC) and rabbit IgG were received from Invitrogen. Nuclei were visualized using DAPI (ProLong Gold antifade reagent with 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole, dihydrochloride (DAPI), P-36931; IHC) nuclear counterstain from Invitrogen.

Human autopsy material

Tissues were provided by the Harvard Brain Tissue Resource Center (McLean Hospital, Belmont, MA, USA), and research was conducted in compliance with policies and principles contained in the Federal Policy for the Protection of Human Subjects. Thirty-two postmortem human brains were used in this study. Eight came from individuals with a clinical diagnosis of early (Braak stage I and II), moderate (Braak stage III and IV), to severe (Braak stage V and VI) AD by histological analyses and 8 came from age-matched, normal controls. Ages at death ranged between 68 and 92 years, with a mean age of 78. Postmortem intervals ranged between 4.98 and 30.65 h, with a mean delay of 16.37 h. The gender, age at death, and postmortem interval were comparable in all groups. Blocks of hippocampus frozen in liquid nitrogen vapor or at -80°C were shipped along with formalin-fixed blocks. Subsequently, the formalin-fixed blocks of tissue were paraffin-embedded and sectioned for IHC, while frozen (non-formalin-fixed) blocks were homogenized to make lysates for WB.

Transgenic mouse lines

Mice over-expressing the human APP695 minigene carrying the Swedish (K670N, M671L) and Indiana (V717F) familial AD mutations downstream of the platelet-derived growth factor B-chain promoter have been previously described (PDAPP mice) (Hsia et al. 1999; Mucke et al. 2000). A G-to-C point mutation was introduced into the PDAPP mice that mutated Asp664 (APP695 numbering) to Ala (D664A; PDAPP D664A mice) (Galvan et al. 2006; Saganich et al. 2006). The construct in which the D664A mutation was introduced was identical to that used in the generation of PDAPP mice, and details of the creation of PDAPP D664A mice have been recently reported (Galvan et al. 2006; Saganich et al. 2006). PDAPP D664A mice produced from this construct were crossed onto the C57BL/6J background for 5-20 generations (B21 line) or created from the same construct directly into the C57BL/6J background (B254 line), and compared with PDAPP mice (J9 and J20 lines were generated and previously characterized, but for simplicity only the J20 line was used in this study) in the same genetic background. Transgenic lines were maintained by crosses with C57BL/6J breeders (Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, ME, USA). Aβ production and plaque deposition, synapse density, astrogliosis, dentate gyral volume, neuronal precursor proliferation, electrophysiology, and behavior of PDAPP(J20) and PDAPP D664A(B254, B21) transgenics when compared with non-transgenic littermates were previously analyzed and described (Galvan et al. 2006; Saganich et al. 2006). Three month old and 13 month old non-transgenic littermates culled from all transgenic lines and PDAPP(J20) and PDAPP D664A(B254, B21) transgenic mice were used in experiments (n ≥ 6 animals per group). The use of animals in this study was in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, and under a protocol approved by the Buck Institute’s Animal Care and Use Program Committee, which is accredited by AAALAC.

Immunohistochemistry

The acquisition and processing of human autopsy samples (n = 8) are described above. Mice (n ≥ 6/group) were perfused with 4% p-formaldehyde in 1× phosphate-buffered saline/Bouin’s solution after deep anesthesia with isoflurane. Brains were removed, post-immersed for 24 h in the same fixative, paraffin embedded, and then cut into 50-μm vibratome sections. Sections were deparaffinized in xylene (2 × 5 min), followed by incubations in 100% (2 × 2 min), 95% (2 × 2 min), 80% (4 min), and 70% (4 min) ethanol. Sections were then washed for 15 min in 1× Tris-buffered saline (TBS). For antigen retrieval, the slides were microwaved at 40% power for 5 min in 10 mmol/L citrate buffer (pH 6.0), allowed to cool for 20 min, and then transferred to 1× TBS for 10 min. Non-specific antigen binding was blocked for 1 h with 10% normal donkey serum/1× TBS, after which sections were incubated overnight at 4°C with phospho-specific rabbit anti-PAK-1/2/3 (Ser141) (1 : 50; 44-940G, Biosource, Camarillo, CA, USA) or rabbit IgG (1 : 500), and or PDI (1 : 100) or mouse IgG (1 : 500) in 1% bovine serum albumin/1× TBS, washed with 1× TBS (3 × 20 min), and then incubated for 1 h with Alexa Fluor488 donkey anti-rabbit (1 : 500) or Alexa Fluor555 donkey anti-mouse serum (1 : 250). Following washings, slides were quick-dried and coverslipped with ProLong Gold antifade reagent with DAPI. For antigen processing of human tissue, sections were brought down to 70% ethanol, incubated for 15 min in Sudan Black B (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA) solution, and then rinsed with double deionized water. Images (three fields per hippocampal region) were captured on a laser-scanning confocal microscope (CLSM; Nikon PCM-2000; Nikon Instruments, Melville, NY, USA) using a 40× objective and a 2× or 4× zoom. Phospho-PAK- or DAPI-immunoreactive cells were counted by processing CLSM images using Adobe Photoshop (Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA, USA), followed by image analysis using the software Spots module in Bitplane Imaris Suite (Bitplane, Zurich, Switzerland). Quantification of phospho-PAK-immunoreactive cells was expressed as a percentage ratio of the number of neurons with positive phospho-PAK staining versus the number of neurons with positive DAPI staining, pseudo-colored red in some images for contrast purposes.

Western blots

Dissected and frozen hippocampi from each human (n = 7) or mouse (n ≥ 6/group) brain sample, or mouse hemi-brains (n ≥ 10) were homogenized in ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline lysis buffer containing 0.05% Nonidet P-40, 0.25% sodium deoxycholate, 50 mmol/L Tris-HCl (pH 8.5), 100 nmol/L NaCl, 1 mmol/L EDTA (pH 8.0), Roche (Mannheim, Germany) complete mini cocktail protease inhibitor, and 2 mg/mL β-glycerol phosphate. Samples were then centrifuged at 16 000 g for 10 min at 4°C, and supernatant was assayed for total protein concentration using a bicinchoninic acid assay kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA). Samples of 40 or 100 μg of protein were added to reducing sample buffer and heated for 10 min at 70°C. Proteins were resolved using sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis with 4-12% or 8-16% Tris-glycine gels and transferred to polyvinyldifluoridine membranes (Schleicher and Schuell, Keene, NH, USA). Membranes were blocked for non-specific binding with 3% or 5% bovine serum albumin in TBS and 0.1% Tween-20. Primary phospho-PAK-1 (Thr423)/PAK-2 (Thr402) (1 : 250) or PAK-1/2/3 (1 : 1000) antibody was used in this same blocking buffer and incubated with membranes overnight at 4°C. After incubation with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies, immunoreactive proteins were detected by enhanced chemiluminescence (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ, USA) and exposed using Kodak Biomax MR film (Kodak Eastman, New Haven, CT, USA). To confirm uniform loading of proteins across conditions, immunoblots were stripped (15 min in 100 mmol/L glycine, pH 2.5, followed by 15 min in 2% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 0.7% 2β-mercaptoethanol, and 62.5 mmol/L Tris-HCl, pH 6.7, 60°C) and reprobed with GAPDH (1 : 1000) for 1 h at 20°C. Blots were quantified by band densitometry of scanned films using NIH Image 1.61 software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA). Phosphorylation of PAK was expressed as a percent ratio of phosphorylated to total proteins. Total PAK quantitations were expressed as a percentage of the ratio of PAK densitometric optical density to that of GAPDH.

Statistics

Pooled raw data from immunoreactive cell counts and band densitometry were statistically analyzed using one-way anvoa (GraphPad Prism software; San Diego, CA, USA), followed by between-group comparisons using the Newman-Keuls test. Statistical significance indicated in graphs reflects statistical analyses of the pooled raw data from all images. p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Mutation of APP caspase cleavage site Asp664 prevents increased phospho-PAK-1/2/3 immunoreactivity in young PDAPP mice

p21-Activated kinase-1 and PAK-3 have been implicated in the pathogenesis of AD (McPhie et al. 2003; Zhao et al. 2006) through the interaction of PAK-3 with the C-terminus of APP (McPhie et al. 2003). Here, we tested the hypothesis that PAK may be an APP-interacting signaling molecule that is active in Alzheimer model mice and regulated by cleavage of APP at Asp664 (or by a protein-protein interaction requiring Asp664). Three established APP lines were used: PDAPP(J20) mice (Hsia et al. 1999; Mucke et al. 2000) and PDAPP D664A(B254, B21) mice with the D664A mutation introduced into the same minigene (Galvan et al. 2006; Saganich et al. 2006). These mice have been previously characterized for Alzheimer-like neuropathology and behavior, whereas Aβ levels and plaque deposition were unaffected, synapse loss, astrogliosis, dentate gyral atrophy, increased neuronal precursor proliferation, and spatial and working memory deficits in PDAPP(J20) mice were prevented by the Asp664 mutation in PDAPP D664A mice.

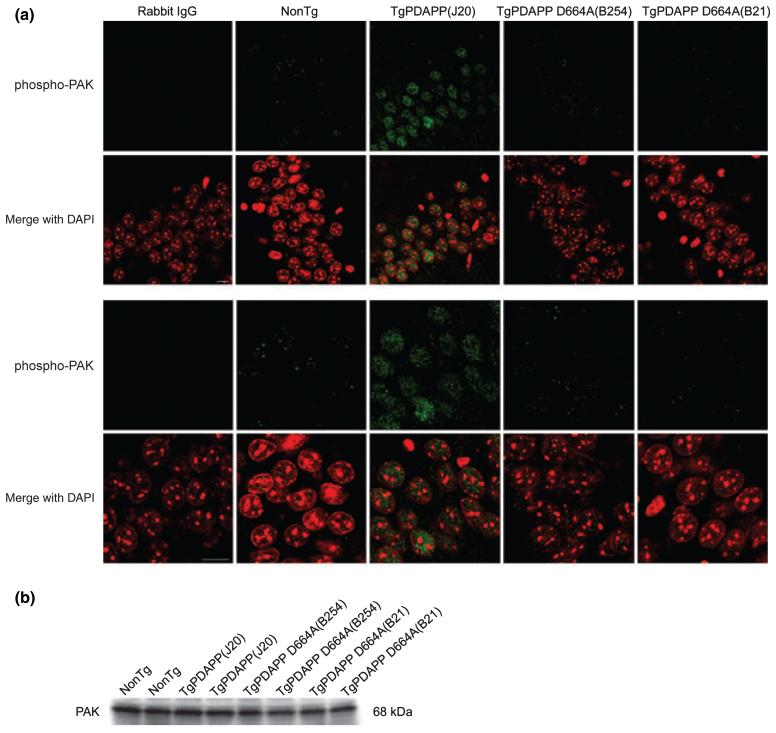

To determine whether PAK activity and expression are affected by over-expressing familial AD-human APP695, and whether this abnormality is reversed once cleavage at Asp664 is prevented, we performed immunohistochemical and immunoblotting studies for PAK-1/2/3 on brains of transgenic PDAPP(J20), PDAPP D664A, and their non-transgenic littermates (controls). In hippocampus of young (3 months) non-transgenic animals of either transgenic line, phospho-PAK immunoreactivity was observed in CA1 neurons (Fig. 1a) using an antibody [phospho-PAK-1/2/3 (Ser141)] that detects endogenous PAK-1, -2, and -3 only when phosphorylated at Ser144, Ser141, and Ser139, respectively (Chong et al. 2001). We chose this age for the initial studies because it is an age at which the Alzheimer model mice (J20) demonstrate behavioral abnormalities such as Y-maze deficits and neophobia, as well as dentate gyral atrophy and electrophysiological deficits, but it is prior to the appearance of senile plaques and hippocampal synaptic loss (Galvan et al. 2006; Saganich et al. 2006). Phospho-PAK-1/2/3 staining was uniformly distributed in and restricted to the nuclei of neurons, as visualized by co-staining with DAPI, consistent with the recently reported nuclear localization of PAK-1 and -3 (Singh et al. 2005; Zhao et al. 2006). PAK-1/2/3 phosphorylation was not evident in glial fibrillary acidic protein-positive astrocytes (data not shown), a finding compatible with that reported by Zhao et al. (2006). However, there was a substantial increase in phospho-PAK-1/2/3 nuclear labeling in PDAPP(J20) transgenic mice when compared with non-transgenic littermates, an effect that was completely prevented in both lines (B254 and B21) of PDAPP D664A mice (Fig. 1a). Immunoblotting with a different phospho-PAK antibody [phospho-PAK-1 (Thr423)/PAK-2 (Thr402)] that recognizes endogenous PAK-1, -2, and -3 only when phosphorylated at Thr423, Thr402, and Thr421, respectively (Zhan et al. 2003), revealed a similar increase in phospho-PAK-1/2/3 of PDAPP(J20) hemi-brains when compared with non-transgenic littermates and PDAPP D664A(B254) mice, which were comparable (Fig. 5a). Phosphorylation at the serine sites (144, 141, and 139) occurs in the kinase inhibitory domain and leads to increased activation of PAK-1/2/3 (Chong et al. 2001). Phosphorylation at the threonine sites (423, 402, and 421) is required to achieve full PAK-1/2/3 activity and maintains the kinase in a catalytically competent state (Zenke et al. 1999).

Fig. 1.

Increased PAK-1/2/3 activation in hippocampus of 3 months PDAPP mice is prevented in PDAPP D664A mice.(a) Hippocampal CA1 neurons of brain sections from non-transgenic (non-Tg) littermates, PDAPP [line J20, PDAPP(J20)] transgenics, and PDAPP mutated at Asp664 [line B254, PDAPP D664A(B254); line B21, PDAPP D664A(B21)] transgenics were immunostained with an antibody against phosphorylation-specific PAK-1/2/3 (Ser141) or rabbit IgG control, followed by Alexa Fluor488 anti-rabbit secondary (green). Nuclei were visualized with DAPI staining, pseudo-colored red. Representative images (n ≥ 6 animals per group) shown were captured on a laser-scanning confocal microscope using a 40× objective and a 2× (top panel) or 4× (bottom panel) zoom. Scale bar: 10 μm. (b) A total of 40 μg each of hippocampal extracts from non-Tg, PDAPP(J20), PDAPP D664A(B254), and PDAPP D664A(B21) brains was examined by western blot using total PAK-1/2/3 (61 kDa PAK-2, 68 kDa PAK-1/3) antibody. Immunoblot pictured is of representative experiments (n = 6 animals per group).

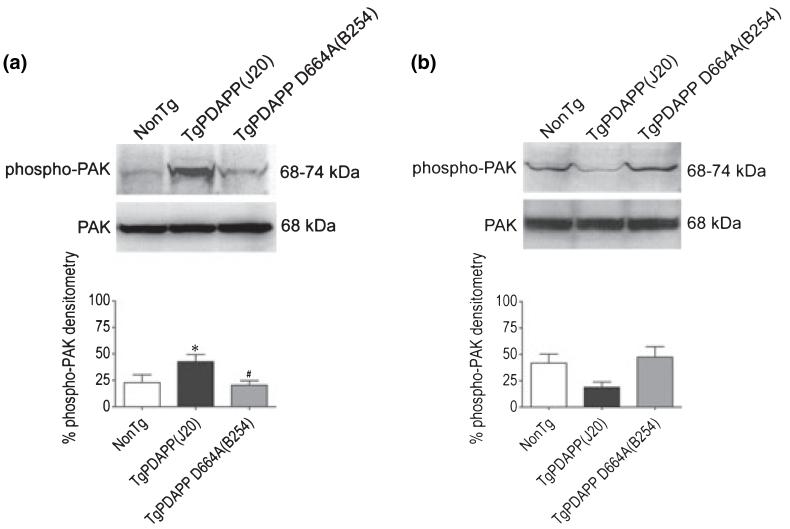

Fig. 5.

Abnormal PAK-1/2/3 activation at Thr423, Thr402, and Thr421 in brains of PDAPP mice is prevented in PDAPP D664A mice. Forty microgram each of protein extracts from (a) 3-month old and (b) 13-month old non-Tg, PDAPP(J20), and PDAPP D664A(B254) brains was examined by western blot using phospho-PAK-1 (Thr423)/PAK-2 (Thr402) (61-67 kDa phospho-PAK-2, 68-74 kDa phospho-PAK-1/3; top immunoblots) and total PAK-1/2/3 (61 kDa PAK-2, 68 kDa PAK-1/3; bottom immunoblots) antibodies. Top and middle panels show representative immunoblots and bottom panels show mean densitometry values (± SEM) for each group (3 months: F = 3.9; df 2,29; p = 0.0321; 13 months: F = 4.2; df 2,30; p = 0.0242) of combined immunoblots (n ≥ 10 animals per group). Phospho-PAK-1/2/3 densitometry is expressed graphically as a percentage of the ratio of phosphorylated to total proteins, with denotation of significance obtained from statistical analyses of pooled raw data. Between-group comparisons were analyzed using the Newman-Keuls test: *p < 0.05 relative to the non-Tg group, #p < 0.05 relative to the PDAPP(J20) group.

To determine whether the increase in active PAK was due to an effect on PAK phosphorylation in the absence of an effect on expression, we assessed hippocampal levels of total PAK-1/2/3 across transgenic and non-transgenic lines. Analysis of WB using a pan PAK-1/2/3 antibody revealed no differences in PAK levels in non-transgenic, PDAPP(J20), or PDAPP D664A(B254, B21) mice (Figs 1b and 5a), suggesting that the phosphorylation (and therefore, activation) of PAK was augmented without an alteration in overall PAK expression. The PAK-1/2/3-immunoreactive band was in the vicinity of 68 kDa, similar to what was found with phospho-PAK-1/2/3 (vicinity 68-74 kDa; Fig. 5). Thus, considering the molecular weights of PAK isoforms, it is most likely that the target PAK was PAK-1 and or -3, as a band for PAK-2 was not observed (61 kDa for PAK-2). The absence of any increase in phospho-PAK in PDAPP D664A(B254, B21) mice even in the presence of very high levels of Aβ1-42 such as in PDAPP D664A(B254) animals (Galvan et al. 2006) is consistent with the hypothesis that the increase in active PAK observed in transgenic PDAPP(J20) mice requires a functional Asp664 cleavage site at the C-terminus of APP (McPhie et al. 2003).

Increased phospho-PAK-1/2/3 immunoreactivity in hippocampal neurons of young PDAPP mice is absent in PDAPP D664A mice

p21-Activated kinase isoforms 1 and 3 have been shown to be differentially distributed in hippocampus (Allen et al. 1998; Ong et al. 2002). To reveal the subfield localization of phospho-PAK in hippocampus, and to determine whether the effect of the D664A mutation is subfield-specific, we quantified the number of phospho-PAK-immunoreactive neurons in 3-month old PDAPP(J20), PDAPP D664A(B254, B21), and non-transgenic control mice. Phospho-PAK-immunoreactive neurons in subfields CA1, CA2, CA3, and in the molecular layer of the dentate gyrus (MLDG) were counted using the Spots module in Bitplane Imaris Suite. As shown in Fig. 2a, the Spots module identified (indicated by a yellow spot over an immunoreactive cell) and summed phospho-PAK-immunoreactive neurons in a specified field. Not only was there greater phospho-PAK-1/2/3 immunoreactivity in each individual cell (Fig. 1a), but there was a significant increase in the total number of hippocampal neurons showing phospho-PAK immunoreactivity in PDAPP(J20) mice when compared with non-transgenic littermates [Hippocampus, non-Tg = 8.3 ± 0.8, TgPDAPP(J20) = 28.8 ± 2] (Fig. 2b). This increase in the number of phospho-PAK-immunoreactive neurons was prevented in PDAPP D664A(B654, B21) mice, in which counts were comparable (though non-significantly below) to those in the non-transgenic group [Hippocampus, TgPDAPP D664A(B254) 3.4 ± 0.7, TgPDAPP D664A(B21) = 5.0 ± 1.1] (Fig. 2b). Specifically, in each subfield of hippocampus [CA1, non-Tg = 11.2 ± 1.7, TgPDAPP(J20) = 31.7 ± 2.3; CA2, non-Tg = 9.6 ± 1.6, TgPDAPP(J20) = 32.0 ± 3.2; CA3, non-Tg = 8.9 ± 1.5, TgPDAPP(J20) = 35.7 ± 4.3; MLDG, non-Tg = 3.6 ± 0.8, TgPDAPP(J20) = 15.7 ± 3.9], there were significantly more phospho-PAK-1/2/3-immunoreactive neurons in PDAPP(J20) mice compared with non-transgenic littermates (20-25%). These increases were not present in PDAPP D664A(B254, B21) mice in any of the subfields [CA1, TgPDAPP D664A(B254) = 5.4 ± 1.9, TgPDAPP D664A(B21) = 8.0 ± 2.9; CA2, TgPDAPP D664A(B254) = 4.0 ± 1.4, TgPDAPP D664A(B21) = 6.7 ± 2.2; CA3, TgPDAPP D664A(B254) = 3.6 ± 1.6, TgPDAPP D664A(B21) = 4.9 ± 1.9; MLDG, TgPDAPP D664A(B254) = 0.7 ± 0.3, TgPDAPP D664A(B21) = 0.6 ± 0.6] (Fig. 2b). The MLDG showed the fewest phospho-PAK-immunoreactive cells across all lines - approximately 5% fewer than the average levels in all groups. Also, the MLDG showed the smallest increase in number of phospho-PAK-immunoreactive cells in transgenic PDAPP(J20) hippocampi (approximately 10% with respect to non-transgenic littermates). WB analyses using the phospho-PAK-1 (Thr423)/PAK-2 (Thr402) antibody confirmed the IHC data: there were significantly higher levels of PAK-1/2/3 phosphorylation in hemi-brains of PDAPP(J20) transgenics in comparison with non-transgenics, and this increase in phosphorylation was prevented in PDAPP D664A(B254) transgenics [non-Tg = 22.8 ± 7.5, TgPDAPP(J20) = 42.6 ± 6.8, TgPDAPP D664A(B254) = 20.3 ± 4.3] (Fig. 5a). Thus, both the levels of PAK activation and the number of neurons showing active PAK were greater in transgenic PDAPP mice. These effects were completely prevented in transgenic mice in which Asp664 was mutated.

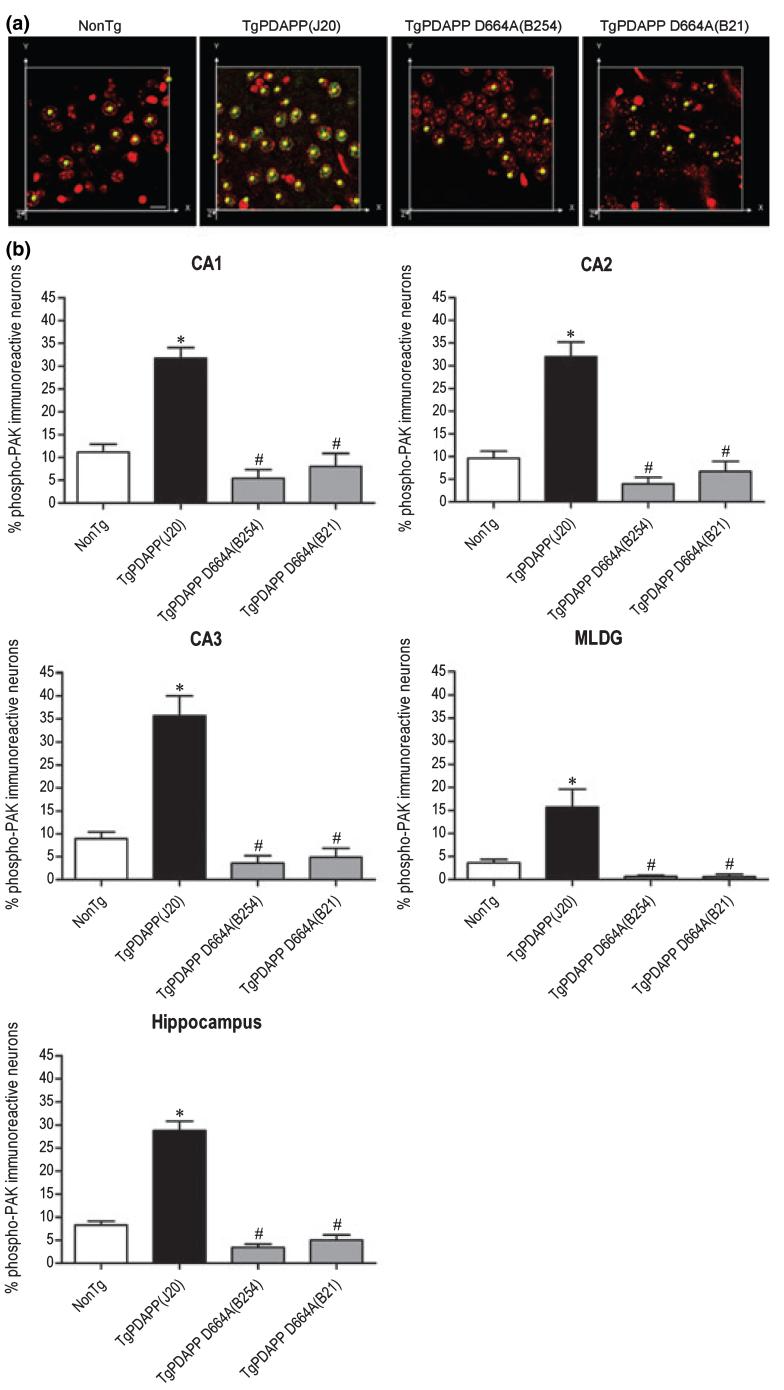

Fig. 2.

Quantitative analysis of PAK-1/2/3 activation in hippocampal subfields of 3-month old PDAPP and PDAPP D664A mice. Hippocampal neurons of brain sections from non-transgenic (non-Tg) littermates, PDAPP [line J20, PDAPP(J20)] transgenics, and PDAPP mutated at Asp664 [line B254, PDAPP D664A(B254); line B21, PDAPP D664A(B21)] transgenics were immunostained with an antibody against phosphorylation-specific PAK-1/2/3 (Ser141) or rabbit IgG control, followed by Alexa Fluor488 anti-rabbit secondary (green). Nuclei were visualized with DAPI staining, pseudo-colored red. Counts of phospho-PAK-1/2/3 or DAPI immunoreactive neurons in CA1, CA2, CA3, and the molecular layer of the dentate gyrus (MLDG) were obtained by processing laser-scanning confocal microscope images, followed by quantification using the software Spots module in Bitplane Imaris Suite. (a) Panel shows representative images (n ≥ 6 animals per group) of Spot counting of phospho-PAK-1/2/3 immunoreactive neurons. Magnification = 80×, scale bar: 10 μm. (b) Graphs show mean phospho-PAK-immunoreactive values (± SEM) for each group (CA1: F = 28.7; df 3,44; p < 0.0001; CA2: F = 33.3; df 3,44; p < 0.0001; CA3: F = 33.8; df 3,44; p < 0.0001; MLDG: F = 12.6; df 3,44; p < 0.0001; Hippocampus: F = 84.7; df 3,188; p < 0.0001) of combined images (n ≥ 6 animals per group). Phospho-PAK immunoreactivity is expressed graphically as a percentage ratio of the number of neurons with positive phospho-PAK-1/2/3 staining versus the number of neurons with positive DAPI staining, with denotations of significance obtained from statistical analyses of pooled raw data. Between-group comparisons were analyzed using the Newman-Keuls test: *p < 0.05 relative to the non-Tg group, #p < 0.05 relative to the PDAPP(J20) group.

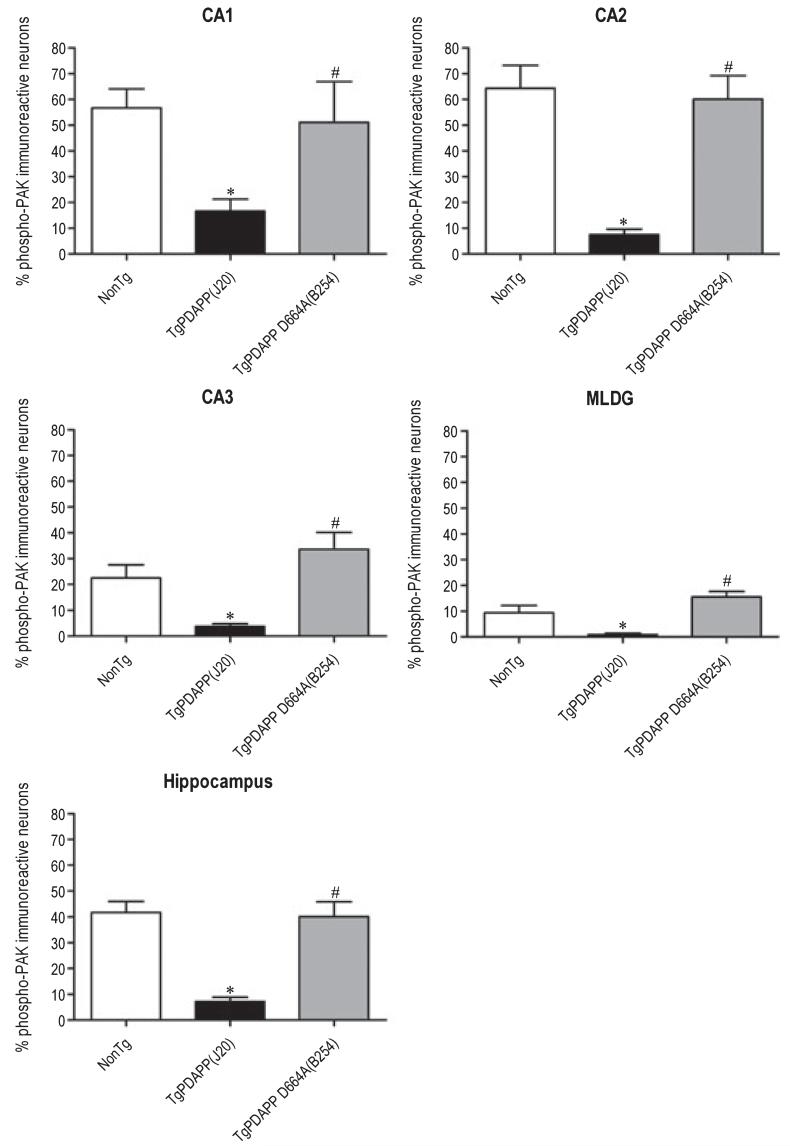

Phospho-PAK-1/2/3 deficits in mature PDAPP mice are restored to normal levels in PDAPP D664A mice

Next, we determined whether the increases in PAK phosphorylation observed in 3-month old transgenic PDAPP(J20) were present in older animals with advanced AD-like pathology such as senile plaques and gliosis (Galvan et al. 2006; Saganich et al. 2006), and whether the effect of the D664A mutation is lost with advancing pathology. We compared both the intensity of and the number of neurons with phospho-PAK labeling in mature (13 months) nontransgenic, PDAPP(J20), and PDAPP D664A(B254) mice. Interestingly, and in contrast to what was observed in 3-month old animals (Figs 1, 2 and 5a), older PDAPP(J20) mice displayed significantly reduced phospho-PAK-1/2/3 immunoreactivity (Fig. 3a) and number of phospho-PAK-immunoreactive neurons (Fig. 4) in comparison with non-transgenic littermates [Hippocampus, non-Tg = 41.7 ± 4.3, TgPDAPP(J20) = 7.2 ± 1.6]. However, just as was observed in 3 months transgenic mice (Figs 1, 2, and 5a), the Asp664 mutation in PDAPP D664A(B254) mice significantly prevented the changes observed in PDAPP mice [Hippocampus, TgPDAPP D664A(B254) = 40.1 ± 5.8] at 13 months (Fig. 4). These results were consistent across all subfields of hippocampus, and in fact, the D664A mutation led to phospho-PAK-1/2/3 levels in CA3 and the MLDG that were slightly greater, though non-significant, than those of non-transgenic mice [CA1, non-Tg = 56.7 ± 7.4, TgPDAPP(J20) = 16.7 ± 4.6, TgPDAPP D664A(B254) = 51.2 ± 15.8; CA2, non-Tg = 64.4 ± 8.9, TgPDAPP(J20) = 7.5 ± 2.1, TgPDAPP D664A(B254) = 60.1 ± 9.1; CA3, non-Tg = 22.5 ± 5.1, TgPDAPP(J20) = 3.7 ± 1.1, TgPDAPP D664A(B254) = 33.6 ± 6.5; MLDG, non-Tg = 9.4 ± 2.8, TgPDAPP(J20) = 1.0 ± 0.5, TgPDAPP D664A(B254) = 15.6 ± 2.1] (Fig. 4).

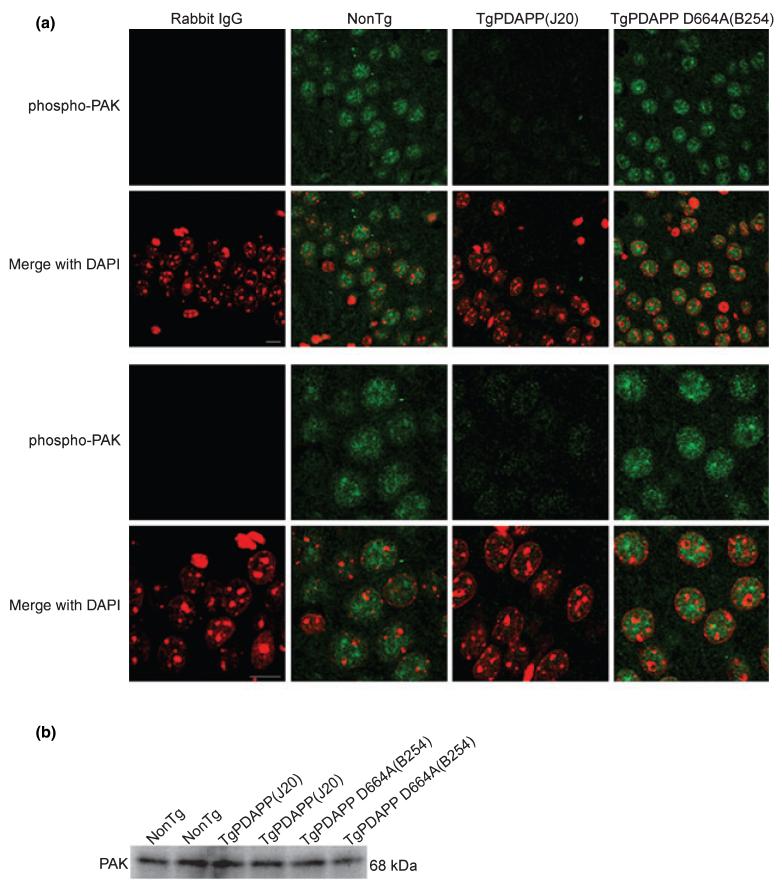

Fig. 3.

Decreased PAK-1/2/3 activation in hippocampus of 13-month old PDAPP mice is prevented in PDAPP D664A mice. (a) Hippocampal CA1 neurons of brain sections from non-transgenic (non-Tg) littermates, PDAPP [line J20, PDAPP(J20)] transgenics, and PDAPP mutated at Asp664 [line B254, PDAPP D664A(B254)] transgenics were immunostained with an antibody against phosphorylated PAK-1/2/3 (Ser141) or rabbit IgG control, followed by Alexa Fluor488 anti-rabbit secondary (green). Nuclei were visualized with DAPI staining, pseudo-colored red. Representative images (n ≥ 6 animals per group) were captured on a laser-scanning confocal microscope using a 40× objective and a 2× (top panel) or 4× (bottom panel) zoom. Scale bar: 10 μm. (a) 40 μg each of hippocampal extracts from non-Tg, PDAPP(J20), and PDAPP D664A(B254) brains was examined by western blot using total PAK-1/2/3 (61 kDa PAK-2 and 68 kDa PAK-1/3) antibody. Immunoblot pictured is of representative experiments (n = 6 animals per group).

Fig. 4.

Quantitative analysis of PAK-1/2/3 activation in hippocampal subfields of 13-month old PDAPP and PDAPP D664A mice. Hippocampal neurons of brain sections from non-transgenic (non-Tg) littermates, PDAPP [line J20, PDAPP(J20)] transgenics, and PDAPP mutated at Asp664 [line B254, PDAPP D664A(B254)] transgenics were immunostained with an antibody against phosphorylated PAK-1/2/3 (Ser141) or rabbit IgG control, followed by Alexa Fluor488 anti-rabbit secondary (green). Nuclei were visualized with DAPI staining, pseudo-colored red. Counts of phospho-PAK-1/2/3 or DAPI immunoreactive neurons in CA1, CA2, CA3, and the molecular layer of the dentate gyrus (MLDG) were obtained by processing laser-scanning confocal microscope images, followed by quantification using the software Spots module in Bitplane Imaris Suite. Graphs show mean phospho-PAK-immunoreactive values (± SEM) for each group (CA1: F = 5.3; df 2,33; p = 0.0101; CA2: F = 9.8; df 2,33; p = 0.0005; CA3: F = 4.8; df 2,33; p = 0.0146; MLDG: F = 8.0; df 2,33; p = 0.0022; Hippocampus: F = 16.2; df 2,132; p < 0.0001) of combined images (n ≥ 6 animals per group). Phospho-PAK immunoreactivity is expressed graphically as a percentage ratio of the number of neurons with positive phospho-PAK-1/2/3 staining versus the number of neurons with positive DAPI staining, with denotations of significance obtained from statistical analyses of pooled raw data. Between-group comparisons were analyzed using the Newman-Keuls test: *p < 0.05 relative to the non-Tg group, #p < 0.05 relative to the PDAPP(J20) group.

Immunoblotting with the phospho-PAK-1 (Thr423)/PAK-2 (Thr402) antibody revealed a similar deficit in phospho-PAK of PDAPP(J20) when compared with non-transgenic littermates and PDAPP D664A(B254) mice, which were comparable (Fig. 5b). That is, there were significantly reduced levels of PAK-1/2/3 phosphorylation in hemibrains of PDAPP(J20) transgenics in comparison with non-transgenics, and this decrease was prevented in PDAPP D664A(B254) transgenics [non-Tg = 41.8 ± 8.5, TgPDAPP(J20) = 18.9 ± 5, TgPDAPP D664A(B254) = 47.5 ± 10] (Fig. 5b). However, WB analysis showed that total PAK-1/2/3 levels were constant across transgenic lines and non-transgenic littermates at 13 months (Figs 3b and 5b). Thus, although strikingly different PAK activation patterns were observed in young (3 months) AD model mice - in which activated PAK was increased several fold - versus older (13 months) AD model mice - in which activated PAK was decreased - in both cases, the D664A mutation prevented the AD-associated changes.

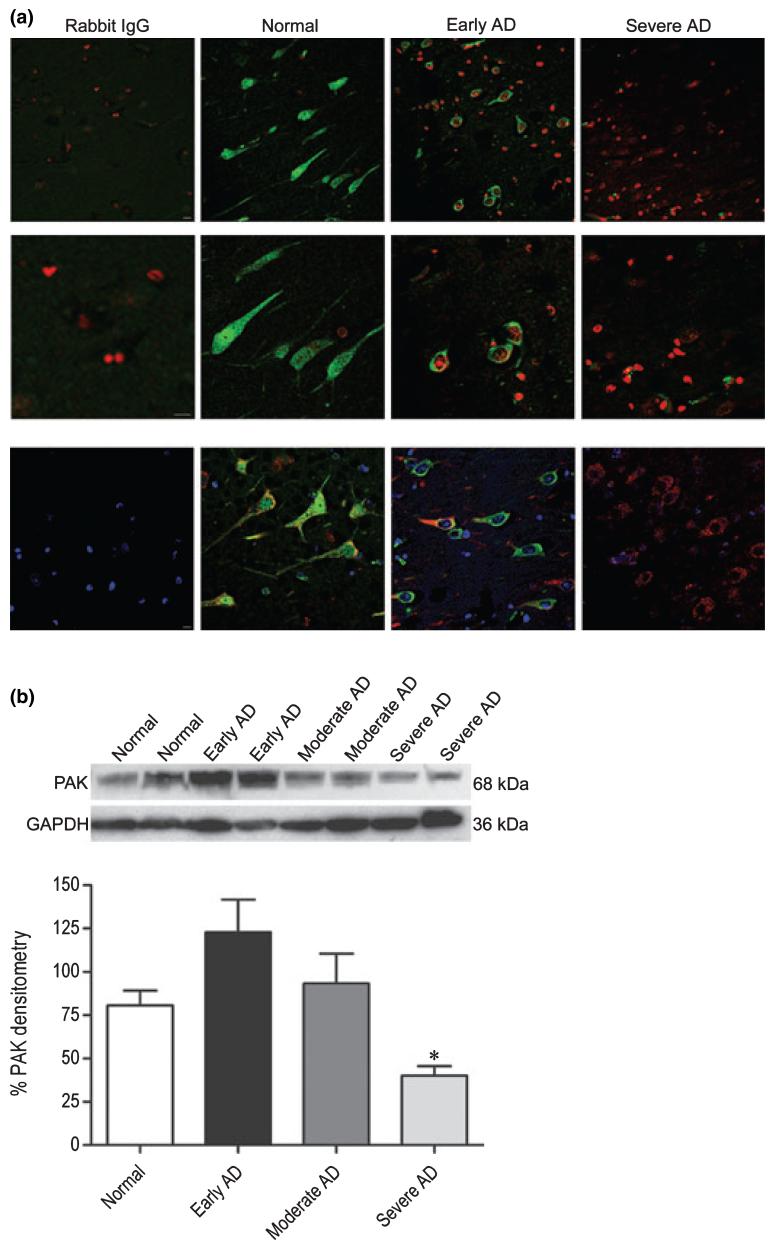

PAK-1/2/3 signaling in Alzheimer disease

Recent evidence from cell culture (McPhie et al. 2003), transgenic mice, and human tissue (Zhao et al. 2006), suggesting a role for PAK-1 and -3 in AD, prompted us to verify whether the PAK changes observed in PDAPP mice extrapolate to human AD. To do so, we performed immunohistochemical labeling for phospho-PAK on postmortem hippocampal sections of age-matched subjects satisfying one of the following neuropathological diagnoses: (i) neuropathologically normal (controls) (Braak stage 0-I, without evidence of other degenerative changes and lacking a clinical history of cognitive impairment), (ii) early AD changes (Braak stage I-II, in the absence of discrete neuropathology), (iii) moderate AD neuropathology (Braak stage III-IV), and (iv) severe AD (Braak stage V-VI with neuropathological diagnosis of AD, in the absence of other neuropathology). Consistent with our findings in 13 months transgenic PDAPP(J20) mice with advanced AD-like pathology (Figs 3, 4, and 5b), we observed a progressive and subcellular-specific decrease in phospho-PAK-1/2/3 immunoreactivity in AD subjects compared with controls (Fig. 6a), as was previously described in moderate Alzheimer cases (Zhao et al. 2006). However, we did not observe the ‘very early’ pattern of increased phospho-PAK that was displayed in the J20 mice at 3 months of age. Furthermore, unlike what was observed in mouse brains, in which phospho-PAK-1/2/3 was entirely nuclear (Figs 1 and 3), diffuse phospho-PAK staining was detected throughout cell bodies and projections of pyramidal neurons in non-diseased human brains, similar to what has been reported using PAK-1- and -3-specific antibodies (Ong et al. 2002; Zhao et al. 2006) (Fig. 6a). In early AD subjects, PAK-1/2/3 phosphorylation was absent in the nucleus and projections, but was present in the soma (Fig. 6a). In contrast, no phospho-PAK immunoreactivity was detected in severe AD cases (Fig. 6a).

Fig. 6.

Selective changes in PAK-1/2/3 activation and expression in the hippocampus of individuals with early, moderate, and severe Alzheimer disease (AD). (a) Brain tissues from age-matched normal (control), early AD, and severe AD subjects were obtained postmortem and immunostained with an antibody against phosphorylated PAK-1/2/3 (Ser141) or rabbit IgG control, followed by Alexa Fluor488 anti-rabbit secondary (green). Nuclei were visualized with DAPI staining, pseudo-colored red. Representative images (n = 8 human cases per group) of pyramidal hippocampal neurons were captured on a laser-scanning confocal microscope using a 40× objective and a 2× (top panel) or 4× (middle panel) zoom. Bottom panel show neurons stained with phospho-PAK-1/2/3 (green), PDI (or mouse IgG control; red), and DAPI (blue) at 40× objective and a 2× zoom. Scale bar: 10 μm. (b) A total of 100 μg each of human hippocampal extracts from normal, early AD, moderate AD, and severe AD pathology was examined by western blot using total PAK-1/2/3 (61 kDa PAK-2, 68 kDa PAK-1/3; top immunoblot) and GAPDH (36 kDa; bottom immunoblot) antibodies. Top and middle panels show representative immunoblots and the bottom panel shows mean densitometry values (± SEM) for each group (F = 6.3; df 3,24; p = 0.0027) of combined immunoblots (n = 7 human cases per group). PAK-1/2/3 densitometry is expressed graphically as a percentage of the ratio of PAK to GAPDH, with denotation of significance obtained from statistical analyses of pooled raw data. Between-group comparisons were analyzed using the Newman-Keuls test: *p < 0.05 relative to Normal cases.

To verify that the loss of phospho-PAK in severe AD subjects was not simply the result of cell death (Cotman and Su 1996; Zhu et al. 2006), we co-stained neurons with the endoplasmic reticulum marker PDI or calregulin along with phospho-PAK-1/2/3 antibodies. As shown in Fig. 6a, neurons in normal, early AD, and severe AD subjects showed a similar pattern of diffuse PDI (in cell bodies and projections of control and early AD cases, and restricted to the cytoplasm for severe AD cases) and calregulin (data not shown) staining, similar to that of phospho-PAK. Thus, even in the extant neurons (that expressed PDI, calregulin, or both), there was a marked reduction in phospho-PAK, arguing that the reduction observed in AD was unlikely to be due simply to neuronal loss. In addition, we determined the expression level of total PAK in hippocampal lysates from normal control subjects and subjects with AD using a pan-PAK (PAK-1/2/3) antibody. Surprisingly, although we found a continuing decline in phospho-PAK-1/2/3 levels with increasing pathology (Fig. 6a), total PAK increased by approximately 75% in early AD subjects versus controls, and then gradually decreased to approximately 30-35% less than control levels in severe AD (normal = 80.7 ± 8.4, early AD = 122.8 ± 18.8, moderate AD = 93.28 ± 17.2, and severe AD = 40.09 ± 5.5) (Fig. 6b). The reduction for phosphorylated PAK was larger than that of total PAK in severe AD cases, suggesting that the activity of PAK in AD patients was reduced beyond that indicated by the reduction in the PAK protein itself. Zhao et al. (2006) reported a similar decrease in total PAK-1 and -3 protein in moderate AD cases. The increase in PAK from normal to early AD subjects did not reach significance because of the large variability within the group. However, the decrease in PAK levels in severe AD with respect to the control group was statistically significant. In contrast, the abundance of a control protein, GAPDH, was unaltered across groups.

Discussion

Recent work suggests that cleavage of APP at Asp664 is a contributing mechanism of AD-related neuropathology and behavioral deficits in a transgenic mouse AD model (Galvan et al. 2006; Saganich et al. 2006). Herein, we report that a signaling kinase is abnormally activated in APP transgenic mice by a mechanism that is dependent on the presence of Asp664. Specifically, we evaluated two interrelated hypotheses: (i) C-terminal cleavage of APP mediates PAK abnormalities seen in AD and AD model mice and (ii) a mutation at Asp664 should prevent these abnormalities. Consistent with our hypotheses, we observed an increase in PAK-1/2/3 phosphorylation in young PDAPP mice, and this increase was completely prevented in PDAPP D664A animals, which carry an uncleavable (by caspases) Asp664 site. Furthermore, the decrease in PAK-1/2/3 phosphorylation in mature PDAPP mice with advanced Alzheimer-like pathology was maintained around non-transgenic levels in PDAPP D664A animals. Importantly, decreased PAK-1/2/3 phosphorylation was also observed in AD subjects. Taken together, the data suggest that the changes in PAK activity observed in AD are mediated by cleavage at Asp664 (or alternatively, by a protein-protein interaction or APP conformation that is prevented by the D664A mutation). As the PDAPP D664A mice develop senile plaques, but no AD-like sequelae, signal transduction events that are prevented by the D664A mutation represent candidate mediators of the Alzheimer phenotype. Although the current work does not prove that PAK abnormalities are required for the AD phenotype, it does provide further support for recent work that implicated PAK-1 and -3 as a potential contributor of AD-related pathophysiology (McPhie et al. 2003; Zhao et al. 2006).

The role of PAK in human disease is an emerging field, and recent evidence from several groups suggests that PAK-1, -3, and -5 regulate neuropathology (McPhie et al. 2003; Matenia et al. 2005) and cognitive health (Zhao et al. 2006) in various AD-related paradigms. For instance, Zhao et al. (2006) observed PAK-1 and -3 losses in hippocampus of 22-month old Tg2576 (Swedish) mice and in subjects with moderate AD. Notably, pharmacological inhibition of PAK in normal mice induced similar PAK-1/3 and AD-associated pathology. Likewise, we observed a comparable decrease in PAK-1/2/3 phosphorylation in both 13-month old PDAPP mice and in early to severe AD subjects, as well as a decrease in overall PAK-1/2/3 concentration in moderate to severe AD. Comparison of our observations in young mice and subjects with early AD pathology is difficult as Zhao et al. did not describe PAK-1 or -3 status at these time-points in the disease progression. Nonetheless, our finding that the PAK-1/2/3 changes in vivo are dependent on the C-terminal tail of APP (and specifically on Asp664) is compatible with their previous hypothesis based on the in vitro findings of McPhie et al. (2003). The finding that the early PAK-1/2/3 activation in transgenic AD model mice (at 3 months) was seen in neither the late course of the disease (13 months) nor in human AD - even in early human AD - raises the possibility that PAK activation may precede clinical diagnosis of AD, and thus may be present in mild cognitive impairment or even pre-mild cognitive impairment. Therefore, PAK-1/2/3 activation may turn out to represent a predictive, or very early, marker for AD.

How PAK activity influences the development of AD-like features in PDAPP mice cannot be ascertained from the experiments performed in this study. However, based on the abundant literature implicating the presence of PAK-1 and -3 in synapse formation and cognitive function (Chechlacz and Gleeson 2003; Zhao et al. 2006), one possibility is that PAK-1/2/3 defects contribute to spatial memory abnormalities as a result of pre-synaptic density loss seen at 8-12 months in PDAPP mice (Masliah and Rockenstein 2000; Galvan et al. 2006; Saganich et al. 2006). Alternatively, it is possible that increases in PAK-1/2/3 signaling are upstream of synaptic loss in PDAPP mice, as it was recently shown that transgenic mice in which PAK-1 activity is inhibited in the post-natal forebrain display larger synapses, increased long-term potentiation, and enhanced mean synaptic strength (Hayashi et al. 2004). Consistent with this hypothesis, we have observed enlarged pre-synaptic densities in brains of aged PDAPP D664A(B21) mice (our unpublished observations). Furthermore, in mouse and human non-diseased brains, Zhao et al. (2006) detected diffuse PAK-1 and -3 activation in the soma and proximal dendrites of neurons, but much stronger nuclear activity. In Tg2576 mice and AD subjects, PAK-1 and -3 were markedly less active throughout and paralleled synaptic cofilin and drebrin loss, as well as memory impairment (Zhao et al. 2006). These observations are consistent in pattern with the decreased levels of PAK-1/2/3 activity that we detected in AD brains. There may thus be a relationship between PAK-1/2/3 signaling deficits in projections of pyramidal neurons and the development of synaptic and cognitive degeneration in the PDAPP model (Hsia et al. 1999; Mucke et al. 2000; Galvan et al. 2006; Saganich et al. 2006).

Until recently, a focus of attention has been on the cytosolic localization and function of PAK-1 and -3 (Ong et al. 2002; Parrini et al. 2005). In this report, we noted that PAK-1/2/3 activation in AD model mice is restricted to the nuclei in hippocampal neurons. Our data agree with studies signifying the importance of nuclear PAK-2, one function of which is apoptosis (Jakobi et al. 2003; Koeppel et al. 2004). Given that our nuclear localization of PAK-1/2/3 is not correlated with significant evidence of apoptosis in human or mouse brains, however, it is not yet clear how nuclear PAK affects AD-like processes. In the nucleus, active PAK-6 and -1/2 can inhibit gene expression and nuclear translocation of such molecules as the androgen receptor (Yang et al. 2001; Schrantz et al. 2004) and nuclear factor of activated T cell (Yablonski et al. 1998; Fenard et al. 2005), respectively, both of which have been implicated in protection against neurodegeneration related to AD (Lehmann et al. 2004; Cano et al. 2005; Pike et al. 2006). Thus, the active PAK-1/2/3 increase in the nucleus of 3-month old PDAPP mice may render them more susceptible to the development of certain AD-associated indices. Conversely, the active PAK-1/2/3 decrease in the nucleus of 13-month old PDAPP mice might be in part because of the emergence of Aβ plaques, as Zhao et al. (2006) observed a similar active PAK-1 and -3 decrease along with intense peri-plaque labeling in Tg2576 mice (Zhao et al. 2006).

Interestingly, we observed different patterns of PAK-1/2/3 activation and expression between PDAPP mice and AD subjects, and between early and later pathology. Several factors may have influenced these patterns. First, the regulation of PAK abundance and activity in transgenic models of AD and in humans may not be similar for the following reasons: (i) staging of AD in the PDAPP mice does not necessarily correspond to staging of the disease in humans, as the appearance of plaques precedes symptoms in humans, but follows symptom onset in mice and (ii) some features of the human disease, such as overt cell loss and τ pathology, are not represented in the mice (Selznick et al. 1999; Dewachter et al. 2000; Gotz et al. 2004; McGowan et al. 2006). Second, the increase in PAK-1/2/3 expression observed in early AD subjects may be consistent with a recent study, which showed that higher PAK-5 levels increase its interaction with the microtubule protein microtubule affinity regulating kinase, causing τ hyperphosphorylation, as seen in early AD (Matenia et al. 2005). Also, depending on the function of PAK (e.g. protein-protein interactions or enzymatic activity) as the disease advances, its activity and expression may be oppositely regulated at two different levels (Oliveira and Drapier 2000; Prickaerts et al. 2006). Lastly, because housekeeping genes may change expression in transgenic models and postmortem tissues of neurodegenerative diseases (Saunders et al. 1997; Lowe et al. 2000; Silver et al. 2006), the level of GAPDH may not accurately reflect equal protein concentration and neuron number across groups; therefore, the changes in PAK might be because of changes in PAK protein expression or secondary protein loss as a result of cell death.

Which PAK isoform(s) (1, 2, and or 3) is involved in the processes observed cannot be determined from our experiments. Zhao et al. (2006) identified a role for PAK-1 and -3 in synapse function and learning, and McPhie et al. (2003) identified isoform-specific effects of PAK on apoptosis: PAK-1 was protective, PAK-2 was neutral, while PAK-3 was pro-apoptotic. As PAK-2 is not, to our knowledge, expressed in brain, and as PAK-1 and -3 are highly expressed in hippocampus (Ong et al. 2002), PAK-1 and or -3 are likely candidates to have a role in the effects observed in our study. Furthermore, the PAK-immunoreactive band ran at a relative molecular mass of approximately 68 kDa, suggestive of PAK-1 or -3, whereas a band at the appropriate relative molecular mass for PAK-2 was not present.

Asp664-dependent PAK-1/2/3 signaling may occur downstream of events initiated by Aβ or independently of Aβ effects (Lu et al. 2003). However, the plethora of data regarding Aβs role in AD favors the former conclusion (Solomon 2004; Gouras et al. 2005). In support of this idea, Zhao et al. (2006) observed increased PAK-1 and -3 activation by inhibiting Aβ in Tg2576 mice, suggesting that Aβ likely mediates, either directly or indirectly, the changes in PAK they observed. A previously proposed hypothesis suggests that many of the actions of Aβ are actually dependent on the interaction of Aβ with APP (Lorenzo et al. 2000; Scheuermann et al. 2001; Lu et al. 2003), precipitating downstream signal transduction events (Koo 2002; Peel et al. 2004; Zambrano et al. 2004; Matsuda et al. 2005), some of which may require cleavage at Asp664 and others of which may not. For example, Aβ-induced toxicity may be initiated by Aβ oligomerization of APP, recruitment of caspases to the C-terminal domain of APP, and cleavage of APP at Asp664 (Lu et al. 2003). It is an intriguing possibility that PAK-1/2/3 signaling may be modulated through an Aβ-APP interaction and that the effect on PAK requires Asp664, as PAK activation is normalized in PDAPP D664A mice. This finding supports earlier work from McPhie et al. (2001), who showed that APP-induced apoptosis depends on the interaction between PAK-3 and the C31 region and is independent of Aβ.

What are the PAK-regulated signaling molecules that may contribute, at least partly, to AD? PAK-1 may contribute to AD pathogenesis by increasing the activity of the estrogen receptor (Rayala et al. 2006a,b), whose activity lowers the risk of AD in post-menopausal women (Chae et al. 2001; Bhavnani 2003; Marin et al. 2003). However, PAK-1 activates mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) cascades such as those mediated by extracellular signal-related kinase (Jiang et al. 2000; Zhong et al. 2003; Qiao et al. 2004) and c-jun N-terminal kinase (Brown et al. 1996; Alahari 2003), which have been proposed to have a role in inducing τ pathology (Ferrer et al. 2001; Sze et al. 2004), Aβ-induced synaptic dysfunction (Savage et al. 2002; Hashimoto and Masliah 2003; Costello and Herron 2004; Xie 2004), and oxidative stress damage (de la Monte et al. 2000; Zhu et al. 2001; Marques et al. 2003). Likewise, PAK-1 may induce signaling from Notch (Vadlamudi et al. 2005), which has been shown to foster γ-secretase activity (Fischer et al. 2005; Wang et al. 2006a). Thus, PAK signaling may have several effects on AD indices at different stages of the disease.

Interestingly, PAK (PAK-1, -3, and -6) is associated with the apoptosis-regulating signal kinase-1/MAPK kinase/p38 MAPK cascade (Seko et al. 1997; Kaur et al. 2005; Wang et al. 2006b). For example, PAK-1 is an upstream activator of MAPK kinase-6 and of p38 MAPK (Dechert et al. 2001; Lee et al. 2001), which upon phosphorylation/activation may enhance glycogen synthase kinase (GSK)-3β activity (Maroni et al. 2003; Ma et al. 2004). This signal transduction MAPK pathway has been demonstrated to play a key role in AD pathogenesis through GSK-3β-mediated neurofibrillary tangles formation, amyloid deposition, and apoptosis (Dalrymple 2002; Peel et al. 2004; Balaraman et al. 2006). We are particularly interested in the PAK-1/3 to p38 MAPK to GSK-3β signaling pathway for the following reasons: It may have an important role in the AD-like phenotype as endogenous apoptosis-regulating signal kinase-1 is up-regulated in CA1 hippocampal neuron bodies and projections of PDAPP mice (Galvan V. and Bredesen D. E., unpublished data); and an increase in GSK-3β activity is present in brains of PDAPP, but not in PDAPP D664A mice (T-V. V. Nguyen and Bredesen D. E., unpublished data). Furthermore, it was shown that one pathway of C31-induced neurotoxicity is associated with the induction of GSK-3β expression (Kim et al. 2003), suggesting a potential relationship between Asp664-dependent PAK-1/2/3 activation and subsequent GSK-3β signaling.

Dysfunction of a cell signaling pathway mediated by APP may be at least one source of the neurodegeneration and consequent dementia in AD. In particular, cleavage of APP at Asp664 has been shown to promote AD-like deficits in a mouse model (Galvan et al. 2006). Recent research suggests that the loss of neurons and synapses and the cognitive problems observed in AD are related to deregulation of PAK-1 and -3 expression and enzymatic activity (McPhie et al. 2003; Zhao et al. 2006). Interestingly, PAK-3 is regulated by APP, behaving as a membrane receptor that mediates the transduction of extracellular signals into the cell via its C-terminus (McPhie et al. 2003). Cellular events are modulated by intracellular pathways that rely on controlled spatial and temporal localization of molecules such as PAK. Deviation in signaling components might trigger cellular dysfunction and contribute to the onset and or progression of disease. In this study, we determined that the PAK-1/2/3 abnormalities present in a transgenic mouse model of AD require APP signaling, and specifically an intact Asp664 site at the C-terminal, intracellular domain of APP. Uncovering the mechanism(s) by which this cleavage site contributes to AD may yield important insights into the signal transduction function of APP, the early processes that promote the disease, as well as the relationship between physiological plasticity and the pathologically altered plasticity in AD.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by grants from the NIH [NS33376 and NS45093 to DEB and AG10671 (ADRC, PI L. Thal)]. T-VVN was supported by NIH Training Grant (AG20495). We thank Molly Susag for administrative assistance.

Abbreviations used

- AD

Alzheimer disease

- APP

amyloid precursor protein

- Aβ

β-amyloid

- D664A

aspartate to alanine mutation at position 664 of APP

- DAPI

4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole, dihydrochloride

- GAPDH

glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- MAPK

mitogen-activated protein kinase

- GSK

glycogen synthase kinase

- MLDG

molecular layer of the dentate gyrus

- PAK

p21-activated kinase

- PDAPP

platelet-derived growth factor B-chain promoter-driven APP transgenic mice

- PDI

protein disulfide isomerase

- TBS

Tris-buffered saline

- WB

western blotting

References

- Alahari SK. Nischarin inhibits Rac induced migration and invasion of epithelial cells by affecting signaling cascades involving PAK. Exp. Cell Res. 2003;288:415–424. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4827(03)00233-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen KM, Gleeson JG, Bagrodia S, Partington MW, MacMillan JC, Cerione RA, Mulley JC, Walsh CA. PAK3 mutation in nonsyndromic X-linked mental retardation. Nat. Genet. 1998;20:25–30. doi: 10.1038/1675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balaraman Y, Limaye AR, Levey AI, Srinivasan S. Glycogen synthase kinase 3β and Alzheimer’s disease: pathophysiological and therapeutic significance. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2006;63:1226–1235. doi: 10.1007/s00018-005-5597-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhavnani BR. Estrogens and menopause: pharmacology of conjugated equine estrogens and their potential role in the prevention of neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2003;85:473–482. doi: 10.1016/s0960-0760(03)00220-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown JL, Stowers L, Baer M, Trejo J, Coughlin S, Chant J. Human Ste20 homologue hPAK1 links GTPases to the JNK MAP kinase pathway. Curr. Biol. 1996;6:598–605. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00546-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cano E, Canellada A, Minami T, Iglesias T, Redondo JM. Depolarization of neural cells induces transcription of the Down syndrome critical region 1 isoform 4 via a calcineurin/nuclear factor of activated T cells-dependent pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:29435–29443. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M506205200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao X, Sudhof TC. A transcriptionally [correction of transcriptively] active complex of APP with Fe65 and histone acetyltransferase Tip60. Science. 2001;293:115–120. doi: 10.1126/science.1058783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chae HS, Bach JH, Lee MW, et al. Estrogen attenuates cell death induced by carboxy-terminal fragment of amyloid precursor protein in PC12 through a receptor-dependent pathway. J. Neurosci. Res. 2001;65:403–407. doi: 10.1002/jnr.1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang KA, Suh YH. Pathophysiological roles of amyloidogenic carboxy-terminal fragments of the β-amyloid precursor protein in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 2005;97:461–471. doi: 10.1254/jphs.cr0050014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang Y, Tesco G, Jeong WJ, Lindsley L, Eckman EA, Eckman CB, Tanzi RE, Guenette SY. Generation of the β-amyloid peptide and the amyloid precursor protein C-terminal fragment gamma are potentiated by FE65L1. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:51100–51107. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309561200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chechlacz M, Gleeson J. Is mental retardation a defect of synapse structure and function? Pediatr. Neurol. 2003;29:11–17. doi: 10.1016/s0887-8994(03)00152-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chong C, Tan L, Lim L, Manser E. The mechanism of PAK activation. Autophosphorylation events in both regulatory and kinase domains control activity. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:17347–17353. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009316200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costello DA, Herron CE. The role of c-Jun N-terminal kinase in the Aβ-mediated impairment of LTP and regulation of synaptic transmission in the hippocampus. Neuropharmacology. 2004;46:655–662. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2003.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotman CW, Su JH. Mechanisms of neuronal death in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Pathol. 1996;6:493–506. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.1996.tb00878.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalrymple SA. p38 mitogen activated protein kinase as a therapeutic target for Alzheimer’s disease. J. Mol. Neurosci. 2002;19:295–299. doi: 10.1385/JMN:19:3:295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dechert MA, Holder JM, Gerthoffer WT. p21-activated kinase 1 participates in tracheal smooth muscle cell migration by signaling to p38 Mapk. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2001;281:C123–C132. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2001.281.1.C123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewachter I, van Dorpe J, Spittaels K, Tesseur I, Van Den Haute C, Moechars D, Van Leuven F. Modeling Alzheimer’s disease in transgenic mice: effect of age and of presenilin1 on amyloid biochemistry and pathology in APP/London mice. Exp. Gerontol. 2000;35:831–841. doi: 10.1016/s0531-5565(00)00149-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenard D, Yonemoto W, de Noronha C, Cavrois M, Williams SA, Greene WC. Nef is physically recruited into the immunological synapse and potentiates T cell activation early after TCR engagement. J. Immunol. 2005;175:6050–6057. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.9.6050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrer I, Blanco R, Carmona M, Puig B. Phosphorylated mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK/ERK-P), protein kinase of 38 kDa (p38-P), stress-activated protein kinase (SAPK/JNK-P), and calcium/calmodulin-dependent kinase II (CaM kinase II) are differentially expressed in tau deposits in neurons and glial cells in tauopathies. J. Neural Transm. 2001;108:1397–1415. doi: 10.1007/s007020100016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer DF, van Dijk R, Sluijs JA, Nair SM, Racchi M, Levelt CN, van Leeuwen FW, Hol EM. Activation of the Notch pathway in Down syndrome: cross-talk of Notch and APP. FASEB J. 2005;19:1451–1458. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-3395.com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galvan V, Chen S, Lu D, Logvinova A, Goldsmith P, Koo EH, Bredesen DE. Caspase cleavage of members of the amyloid precursor family of proteins. J. Neurochem. 2002;82:283–294. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.00970.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galvan V, Gorostiza OF, Banwait S, et al. Reversal of Alzheimer’s-like pathology and behavior in human APP transgenic mice by mutation of Asp664. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:7130–7135. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509695103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glabe CG. Intracellular mechanisms of amyloid accumulation and pathogenesis in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Mol. Neurosci. 2001;17:137–145. doi: 10.1385/JMN:17:2:137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotz J, Streffer JR, David D, Schild A, Hoerndli F, Pennanen L, Kurosinski P, Chen F. Transgenic animal models of Alzheimer’s disease and related disorders: histopathology, behavior and therapy. Mol. Psychiatry. 2004;9:664–683. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gouras GK, Almeida CG, Takahashi RH. Intraneuronal Aβ accumulation and origin of plaques in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol. Aging. 2005;26:1235–1244. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2005.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto M, Masliah E. Cycles of aberrant synaptic sprouting and neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s and dementia with Lewy bodies. Neurochem. Res. 2003;28:1743–1756. doi: 10.1023/a:1026073324672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi ML, Choi SY, Rao BS, Jung HY, Lee HK, Zhang D, Chattarji S, Kirkwood A, Tonegawa S. Altered cortical synaptic morphology and impaired memory consolidation in forebrain-specific dominant-negative PAK transgenic mice. Neuron. 2004;42:773–787. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsia AY, Masliah E, McConlogue L, Yu GQ, Tatsuno G, Hu K, Kholodenko D, Malenka RC, Nicoll RA, Mucke L. Plaque-independent disruption of neural circuits in Alzheimer’s disease mouse models. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:3228–3233. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.6.3228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyman BT, Tanzi R. Amyloid, dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. Curr. Opin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 1992;5:88–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakobi R, McCarthy CC, Koeppel MA, Stringer DK. Caspase-activated PAK-2 is regulated by subcellular targeting and proteasomal degradation. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:38675–38685. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306494200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang K, Zhong B, Gilvary DL, Corliss BC, Hong-Geller E, Wei S, Djeu JY. Pivotal role of phosphoinositide-3 kinase in regulation of cytotoxicity in natural killer cells. Nat. Immunol. 2000;1:419–425. doi: 10.1038/80859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaur R, Liu X, Gjoerup O, Zhang A, Yuan X, Balk SP, Schneider MC, Lu ML. Activation of p21-activated kinase 6 by MAP kinase kinase 6 and p38 MAP kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:3323–3330. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406701200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HS, Kim EM, Lee JP, et al. C-terminal fragments of amyloid precursor protein exert neurotoxicity by inducing glycogen synthase kinase-3β expression. FASEB J. 2003;17:1951–1953. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-0106fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koeppel MA, McCarthy CC, Moertl E, Jakobi R. Identification and characterization of PS-GAP as a novel regulator of caspase-activated PAK-2. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:53653–53664. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410530200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koo EH. The β-amyloid precursor protein (APP) and Alzheimer’s disease: does the tail wag the dog? Traffic. 2002;3:763–770. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2002.31101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SH, Eom M, Lee SJ, Kim S, Park HJ, Park D. BetaPix-enhanced p38 activation by Cdc42/Rac/PAK/MKK3/6-mediated pathway. Implication in the regulation of membrane ruffling. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:25066–25072. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M010892200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HG, Casadesus G, Zhu X, Joseph JA, Perry G, Smith MA. Perspectives on the amyloid-β cascade hypothesis. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2004;6:137–145. doi: 10.3233/jad-2004-6205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann DJ, Hogervorst E, Warden DR, Smith AD, Butler HT, Ragoussis J. The androgen receptor CAG repeat and serum testosterone in the risk of Alzheimer’s disease in men. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 2004;75:163–164. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzo A, Yuan M, Zhang Z, Paganetti PA, Sturchler-Pierrat C, Staufenbiel M, Mautino J, Vigo FS, Sommer B, Yankner BA. Amyloid β interacts with the amyloid precursor protein: a potential toxic mechanism in Alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Neurosci. 2000;3:460–464. doi: 10.1038/74833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe DA, Degens H, Chen KD, Alway SE. Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase varies with age in glycolytic muscles of rats. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2000;55:B160–B164. doi: 10.1093/gerona/55.3.b160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu DC, Rabizadeh S, Chandra S, Shayya RF, Ellerby LM, Ye X, Salvesen GS, Koo EH, Bredesen DE. A second cytotoxic proteolytic peptide derived from amyloid β-protein precursor. Nature Med. 2000;6:397–404. doi: 10.1038/74656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu DC, Soriano S, Bredesen DE, Koo EH. Caspase cleavage of the amyloid precursor protein modulates amyloid β-protein toxicity. J. Neurochem. 2003;87:733–741. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.02059.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma C, Wang J, Luo J. Activation of nuclear factor kappa B by diesel exhaust particles in mouse epidermal cells through phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt signaling pathway. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2004;67:1975–1983. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2004.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marin R, Guerra B, Hernandez-Jimenez JG, Kang XL, Fraser JD, Lopez FJ, Alonso R. Estradiol prevents amyloid-β peptide-induced cell death in a cholinergic cell line via modulation of a classical estrogen receptor. Neuroscience. 2003;121:917–926. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(03)00464-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maroni P, Bendinelli P, Tiberio L, Rovetta F, Piccoletti R, Schiaffonati L. In vivo heat-shock response in the brain: signalling pathway and transcription factor activation. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 2003;119:90–99. doi: 10.1016/j.molbrainres.2003.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marques CA, Keil U, Bonert A, Steiner BS, Haass C, Muller WE, Eckert A. Neurotoxic mechanisms caused by the Alzheimer’s disease-linked Swedish amyloid precursor protein mutation: oxidative stress, caspases, and the JNK pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:28294–28302. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212265200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masliah E, Rockenstein E. Genetically altered transgenic models of Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neural Transm. Suppl. 2000;59:175–183. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-6781-6_20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matenia D, Griesshaber B, Li XY, Thiessen A, Johne C, Jiao J, Mandelkow E, Mandelkow EM. PAK5 kinase is an inhibitor of MARK/Par-1, which leads to stable microtubules and dynamic actin. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2005;16:4410–4422. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-01-0081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda S, Giliberto L, Matsuda Y, Davies P, McGowan E, Pickford F, Ghiso J, Frangione B, D’Adamio L. The familial dementia BRI2 gene binds the Alzheimer gene amyloid-β precursor protein and inhibits amyloid-β production. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:28912–28916. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C500217200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGowan E, Eriksen J, Hutton M. A decade of modeling Alzheimer’s disease in transgenic mice. Trends Genet. 2006;22:281–289. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2006.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McPhie DL, Golde T, Eckman CB, Yager D, Brant JB, Neve RL. β-Secretase cleavage of the amyloid precursor protein mediates neuronal apoptosis caused by familial Alzheimer’s disease mutations. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 2001;97:103–113. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(01)00294-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McPhie DL, Coopersmith R, Hines-Peralta A, Chen Y, Ivins KJ, Manly SP, Kozlowski MR, Neve KA, Neve RL. DNA synthesis and neuronal apoptosis caused by familial Alzheimer disease mutants of the amyloid precursor protein are mediated by the p21 activated kinase PAK3. J. Neurosci. 2003;23:6914–6927. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-17-06914.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de la Monte SM, Ganju N, Feroz N, Luong T, Banerjee K, Cannon J, Wands JR. Oxygen free radical injury is sufficient to cause some Alzheimer-type molecular abnormalities in human CNS neuronal cells. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2000;2:261–281. doi: 10.3233/jad-2000-23-406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mucke L, Masliah E, Yu GQ, Mallory M, Rockenstein EM, Tatsuno G, Hu K, Kholodenko D, Johnson-Wood K, McConlogue L. High-level neuronal expression of Aβ 1-42 in wild-type human amyloid protein precursor transgenic mice: synaptotoxicity without plaque formation. J. Neurosci. 2000;20:4050–4058. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-11-04050.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto T, Takeda S, Murayama Y, Ogata E, Nishimoto I. Ligand-dependent G protein coupling function of amyloid transmembrane precursor. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:4205–4208. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.9.4205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira L, Drapier JC. Down-regulation of iron regulatory protein 1 gene expression by nitric oxide. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:6550–6555. doi: 10.1073/pnas.120571797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong WY, Wang XS, Manser E. Differential distribution of α and β isoforms of p21-activated kinase in the monkey cerebral neocortex and hippocampus. Exp. Brain Res. 2002;144:189–199. doi: 10.1007/s00221-002-1016-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parrini MC, Matsuda M, de Gunzburg J. Spatiotemporal regulation of the Pak1 kinase. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2005;33:646–648. doi: 10.1042/BST0330646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peel AL, Sorscher N, Kim JY, Galvan V, Chen S, Bredesen DE. Tau phosphorylation in Alzheimer’s disease: potential involvement of an APP-MAP kinase complex. Neuromolecular Med. 2004;5:205–218. doi: 10.1385/NMM:5:3:205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pike CJ, Rosario ER, Nguyen TV. Androgens, aging, and Alzheimer’s disease. Endocrine. 2006;29:233–241. doi: 10.1385/ENDO:29:2:233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prickaerts J, Moechars D, Cryns K, Lenaerts I, van Craenendonck H, Goris I, Daneels G, Bouwknecht JA, Steckler T. Transgenic mice overexpressing glycogen synthase kinase 3β: a putative model of hyperactivity and mania. J. Neurosci. 2006;26:9022–9029. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5216-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiao M, Shapiro P, Kumar R, Passaniti A. Insulin-like growth factor-1 regulates endogenous RUNX2 activity in endothelial cells through a phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/ERK-dependent and Akt-independent signaling pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:42709–42718. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404480200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rayala SK, Molli PR, Kumar R. Nuclear p21-activated kinase 1 in breast cancer packs off tamoxifen sensitivity. Cancer Res. 2006a;66:5985–5988. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rayala SK, Talukder AH, Balasenthil S, Tharakan R, Barnes CJ, Wang RA, Aldaz M, Khan S, Kumar R. P21-activated kinase 1 regulation of estrogen receptor-α activation involves serine 305 activation linked with serine 118 phosphorylation. Cancer Res. 2006b;66:1694–1701. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy PH. Amyloid precursor protein-mediated free radicals and oxidative damage: implications for the development and progression of Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neurochem. 2006;96:1–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03530.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russo C, Venezia V, Repetto E, Nizzari M, Violani E, Carlo P, Schettini G. The amyloid precursor protein and its network of interacting proteins: physiological and pathological implications. Brain Res. Brain Res. Rev. 2005;48:257–264. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2004.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saganich MJ, Schroeder BE, Galvan V, Bredesen DE, Koo EH, Heinemann SF. Deficits in synaptic transmission and learning in amyloid precursor protein (APP) transgenic mice require C-terminal cleavage of APP. J. Neurosci. 2006;26:13428–13436. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4180-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders PA, Chalecka-Franaszek E, Chuang DM. Subcellular distribution of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase in cerebellar granule cells undergoing cytosine arabinoside-induced apoptosis. J. Neurochem. 1997;69:1820–1828. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1997.69051820.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savage MJ, Lin YG, Ciallella JR, Flood DG, Scott RW. Activation of c-Jun N-terminal kinase and p38 in an Alzheimer’s disease model is associated with amyloid deposition. J. Neurosci. 2002;22:3376–3385. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-09-03376.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheuermann S, Hambsch B, Hesse L, Stumm J, Schmidt C, Beher D, Bayer TA, Beyreuther K, Multhaup G. Homodimerization of amyloid precursor protein and its implication in the amyloidogenic pathway of Alzheimer’s disease. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:33923–33929. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105410200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrantz N, da Silva Correia J, Fowler B, Ge Q, Sun Z, Bokoch GM. Mechanism of p21-activated kinase 6-mediated inhibition of androgen receptor signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:1922–1931. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311145200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seko Y, Takahashi N, Tobe K, Kadowaki T, Yazaki Y. Hypoxia and hypoxia/reoxygenation activate p65PAK, p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), and stress-activated protein kinase (SAPK) in cultured rat cardiac myocytes. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1997;239:840–844. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.7570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selznick LA, Holtzman DM, Han BH, Gokden M, Srinivasan AN, Johnson EMJ, Roth KA. In situ immunodetection of neuronal caspase-3 activation in Alzheimer disease. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 1999;58:1020–1026. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199909000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silver N, Best S, Jiang J, Thein SL. Selection of house-keeping genes for gene expression studies in human reticulocytes using real-time PCR. BMC Mol. Biol. 2006;7:33–42. doi: 10.1186/1471-2199-7-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh RR, Song C, Yang Z, Kumar R. Nuclear localization and chromatin targets of p21-activated kinase 1. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:18130–18137. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412607200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon B. Alzheimer’s disease and immunotherapy. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 2004;1:149–163. doi: 10.2174/1567205043332126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephan A, Laroche S, Davis S. Generation of aggregated β-amyloid in the rat hippocampus impairs synaptic transmission and plasticity and causes memory deficits. J. Neurosci. 2001;21:5703–5714. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-15-05703.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sze CI, Su M, Pugazhenthi S, Jambal P, Hsu LJ, Heath J, Schultz L, Chang NS. Down-regulation of WW domain-containing oxidoreductase induces Tau phosphorylation in vitro. A potential role in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:30498–30506. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401399200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vadlamudi RK, Manavathi B, Singh RR, Nguyen D, Li F, Kumar R. An essential role of Pak1 phosphorylation of SHARP in Notch signaling. Oncogene. 2005;24:4591–4596. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang R, Zhang YW, Zhang X, Liu R, Zhang X, Hong S, Xia K, Xia J, Zhang Z, Xu H. Transcriptional regulation of APH-1A and increased gamma-secretase cleavage of APP and Notch by HIF-1 and hypoxia. FASEB J. 2006a;20:1275–1277. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-5839fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang RA, Zhang H, Balasenthil S, Medina D, Kumar R. PAK1 hyperactivation is sufficient for mammary gland tumor formation. Oncogene. 2006b;25:2931–2936. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie CW. Calcium-regulated signaling pathways: role in amyloid β-induced synaptic dysfunction. Neuromolecular Med. 2004;6:53–64. doi: 10.1385/NMM:6:1:053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yablonski D, Kane LP, Qian D, Weiss A. A Nck-Pak1 signaling module is required for T-cell receptor-mediated activation of NFAT, but not of JNK. EMBO J. 1998;17:5647–5657. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.19.5647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang F, Li X, Sharma M, Zarnegar M, Lim B, Sun Z. Androgen receptor specifically interacts with a novel p21-activated kinase, PAK6. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:15345–15353. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M010311200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zambrano N, Gianni D, Bruni P, Passaro F, Telese F, Russo T. Fe65 is not involved in the platelet-derived growth factor-induced processing of Alzheimer’s amyloid precursor protein, which activates its caspase-directed cleavage. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:16161–16169. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311027200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zenke FT, King CC, Bohl BP, Bokoch GM. Identification of a central phosphorylation site in p21-activated kinase regulating autoinhibition and kinase activity. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:32565–32573. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.46.32565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhan Q, Ge Q, Ohira T, VanDyke T, Badwey JA. p21-activated kinase 2 in neutrophils can be regulated by phosphorylation at multiple sites and by a variety of protein phosphatases. J. Immunol. 2003;171:3785–3793. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.7.3785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao M, Su J, Head E, Cotman CW. Accumulation of caspase cleaved amyloid precursor protein represents an early neurodegenerative event in aging and in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol. Dis. 2003;14:391–403. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2003.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao L, Ma QL, Calon F, et al. Role of p21-activated kinase pathway defects in the cognitive deficits of Alzheimer disease. Nat. Neurosci. 2006;9:234–242. doi: 10.1038/nn1630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong B, Jiang K, Gilvary DL, Epling-Burnette PK, Ritchey C, Liu J, Jackson RJ, Hong-Geller E, Wei S. Human neutrophils utilize a Rac/Cdc42-dependent MAPK pathway to direct intracellular granule mobilization toward ingested microbial pathogens. Blood. 2003;101:3240–3248. doi: 10.1182/blood-2001-12-0180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu X, Castellani RJ, Takeda A, Nunomura A, Atwood CS, Perry G, Smith MA. Differential activation of neuronal ERK, JNK/SAPK and p38 in Alzheimer disease: the ‘two hit’ hypothesis. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2001;123:39–46. doi: 10.1016/s0047-6374(01)00342-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu X, Raina AK, Perry G, Smith MA. Apoptosis in Alzheimer disease: a mathematical improbability. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 2006;3:393–396. doi: 10.2174/156720506778249470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]