Abstract

Adolescence is often thought of as a period during which the quality of parent–child interactions can be relatively stressed and conflictual. There are individual differences in this regard, however, with only a modest percent of youths experiencing extremely conflictual relationships with their parents. Nonetheless, there is relatively little empirical research on factors in childhood or adolescence that predict individual differences in the quality of parent–adolescent interactions when dealing with potentially conflictual issues. Understanding such individual differences is critical because the quality of both parenting and the parent–adolescent relationship is predictive of a range of developmental outcomes for adolescents.

The goals of the research were to examine dispositional and parenting predictors of the quality of parents’ and their adolescent children’s emotional displays (anger, positive emotion) and verbalizations (negative or positive) when dealing with conflictual issues, and if prediction over time supported continuity versus discontinuity in the factors related to such conflict. We hypothesized that adolescents’ and parents’ conflict behaviors would be predicted by both childhood and concurrent parenting and child dispositions (and related problem behaviors) and that we would find evidence of both parent- and child-driven pathways.

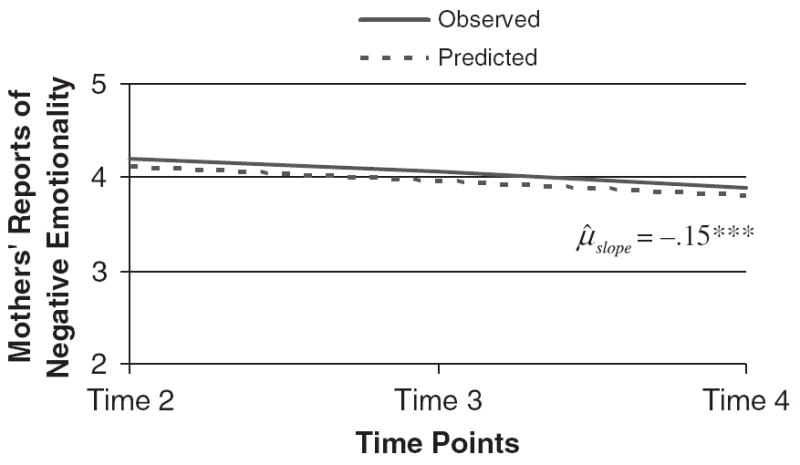

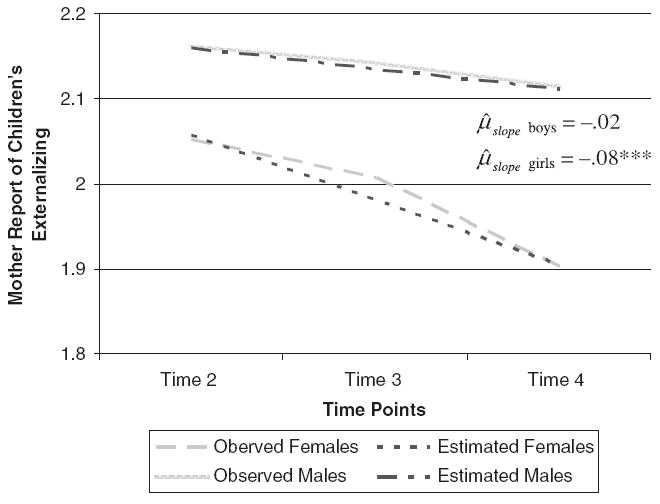

Mothers and adolescents (N = 126, M age = 13 years) participated in a discussion of conflictual issues. A multimethod, multireporter (mother, teacher, and sometimes adolescent reports) longitudinal approach (over 4 years) was used to assess adolescents’ dispositional characteristics (control/regulation, resiliency, and negative emotionality), youths’ externalizing problems, and parenting variables (warmth, positive expressivity, discussion of emotion, positive and negative family expressivity). Higher quality conflict reactions (i.e., less negative and/or more positive) were related to both concurrent and antecedent measures of children’s dispositional characteristics and externalizing problems, with findings for control/regulation and negative emotionality being much more consistent for daughters than sons. Higher quality conflict reactions were also related to higher quality parenting in the past, positive rather than negative parent–child interactions during a contemporaneous nonconflictual task, and reported intensity of conflict in the past month. In growth curves, conflict quality was primarily predicted by the intercept (i.e., initial levels) of dispositional measures and parenting, although maintenance or less decrement in positive parenting, greater decline in child externalizing problems, and a greater increase in control/regulation over time predicted more desirable conflict reactions. In structural equation models in which an aspect of parenting and a child dispositional variable were used to predict conflict reactions, there was continuity of both type of predictors, parenting was a unique predictor of mothers’ (but not adolescents’) conflict reactions (and sometimes mediated the relations of child dispositions to conflict reactions), and child dispositions uniquely predicted adolescents’ reactions and sometimes mothers’ conflict reactions. The findings suggest that parent–adolescent conflict may be influenced by both child characteristics and quality of prior and concurrent parenting, and that in this pattern of relations, child effects are more evident than parent effects.

I. INTRODUCTION AND CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK

Adolescence, although no longer thought of as necessarily a period of “storm and stress” (Arnett, 1999), remains a period of heightened negative emotionality both in terms of individuals’ experience and in interactions with others, particularly with parents (Larson & Lampman-Petraitis, 1989). Simultaneous with these increases in negativity are decreases in the closeness felt between parents and youths (Collins & Steinberg, 2006; McGue, Elkins, Walden, & Iacono, 2005; Smetana, Campione-Barr, & Metzger, 2006). Thus, adolescence continues to be thought of as a period during which the quality of parent–child interactions can be relatively stressed and conflictual. There are individual differences in this regard, however, with only approximately 5–15% of youths experiencing extremely conflictual relationships with their parents (Collins & Laursen, 2004; Smetana et al., 2006). Nonetheless, there is relatively little empirical research on factors in childhood or adolescence that predict individual differences in the quality of parent–adolescent interactions when dealing with potentially conflictual issues. Understanding such individual differences is critical because the quality of both parenting and the parent–adolescent relationship is predictive of a range of developmental outcomes for adolescents (see Collins & Steinberg, 2006).

The purpose of the research in this monograph was to examine child and parenting variables related to individual differences in the verbal and nonverbal emotional reactions of youths and their parents when discussing topics of disagreement. Briefly stated, our general hypothesis in this research was that individual differences in the intensity of mother–child conflict-related interactions in adolescence stem from childhood, as well as concurrent, quality of parenting and child dispositions. Thus, the quality of concurrent and longitudinal relations of emotion-related parenting, concurrent and prior youths’ temperament/personality, and recently occurring conflict were examined as correlates and predictors of parents’ and youths’ conflict reactions. (Note that here and throughout we use the terms “predict” and “predictors” to refer to relations across time, and not to imply causality.) Figure 1 provides a schematic for our conceptual framework in which prior levels of dispositional variables and quality of parenting (which affect one another over time), as well as change in these variables, are expected to predict subsequent parent–adolescent conflict reactions. In particular, we examined several issues: (1) the relation of quality of mothers’ and youths’ conflict reactions to children’s concurrent and previously assessed dispositional characteristics (i.e., regulation/control, negative emotionality, and personality resiliency) and externalizing problems, and whether the quality of conflict reactions was predicted from the initial levels 4 years prior and patterns of change in children’s dispositional characteristics; (2) the relation of quality of conflict reactions to quality of concurrent and prior parenting (i.e., parental positive affect and warmth), as well as recent parent–adolescent conflict, and whether the quality of conflict reactions was predicted from the initial levels and patterns of change in parenting; (3) the degree to which quality of both mothers’ and youths’ conflict reactions were uniquely predicted by child dispositional variables versus parenting quality; and (4) if parenting mediated the relations of child dispositions to the quality of conflict reactions or vice versa (i.e., if child dispositional variables mediated the relations of parenting to conflict reactions) over time. The latter issue concerns the degree to which the process tends to be child-driven or parent-driven across time, or both. We hypothesized that adolescents’ and parents’ conflict behaviors would be predicted by both childhood and concurrent parenting and child dispositions (and related problem behaviors) and that we would find evidence of both parent- and child-driven pathways. Longitudinal data from three assessments, each 2 years apart, were the bases of the analyses.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model.

In the introduction of this monograph, we first discuss general findings on parent–adolescent conflict and the relation of individual differences in the quality of such conflict to adolescent outcomes. This review is to establish the importance of the topic and to provide a background for the study. Next we discuss theoretical approaches for conceptualizing patterns of change from childhood to adolescence that affected our conceptual framework and predictions. Then we turn to issues that are more directly related to specific questions in this monograph, including the prediction of the quality of parent–child interactions from both parenting and children’s dispositional characteristics. As part of this discussion, the dispositional characteristics of children assessed in this study—control/regulation, personality resiliency, and negative emotionality—are defined and placed in a conceptual context; moreover, data on the continuity of such behavior from childhood into adolescence are briefly reviewed. Next, moderation of parent–adolescent conflict and related constructs by sex of the adolescent is examined. Finally, the present study and our hypotheses are outlined.

PARENT–ADOLESCENT CONFLICT: WHAT IS KNOWN AND WHY IS IT IMPORTANT?

As noted by Smetana et al. (2006) and Steinberg and Silk (2002), the nature and quality of adolescents’ relationships with their parents—including conflict and harmony—are among the most researched topics in the adolescent literature. Although there are plentiful data indicating that adolescence usually is not nearly as tumultuous as its reputation (Arnett, 1999), adolescence is perceived by parents as a challenging stage of child-rearing. Bickering and squabbling over everyday issues such as chores and responsibilities, household rules, school, autonomy, privileges, and standards of behavior are commonplace for parents and their adolescents, especially during early adolescence (Collins & Laursen, 2004; Laursen, 1995; Smetana, 1996). In contrast, frequent, high-intensity conflict is not normative during adolescence (Arnett, 1999; Steinberg & Silk, 2002). Nonetheless, although parents and youths tend to view their relationships with one another as supportive (Richardson, Galambos, Schulenberg, & Petersen, 1984), they report less frequent expressions of positive emotion and more frequent negative emotion in early to mid-adolescence than during the preadolescent period (Collins & Steinberg, 2006; Larson, Richards, Moneta, Holmbeck, & Duckett, 1996).

Using meta-analytic procedures, Laursen, Coy, and Collins (1998) examined changes in frequency and intensity of parent–child conflict as youths move into and through adolescence. They found that although the number of conflicts between parents and youths may actually decline across adolescence, there appears to be a mild increase in the negative-affective intensity of parent–child conflicts from early to mid-adolescence (also see Smetana et al., 2006). Additional analyses indicated that the small increase in conflict-related negative affect between early and mid-adolescence was reliably demonstrated only in the father–son dyad or for youths’, rather than parents’, reports of affect. Studies since the 1998 meta-analysis suggest that the increase in adolescents’ negative affect toward parents from early to mid adolescence during potentially conflictual discussions can be substantial (Kim, Conger, Lorenz, & Elder, 2001) and that disagreements, anger, and tension with parents increase from age 11 to 14, especially for girls (McGue et al., 2005), whereas positive parental affect declines substantially (Loeber et al., 2000).

Perhaps because adolescents’ relationships with their mothers tend to be closer than those with their fathers (Richardson et al., 1984), conflict between mothers and adolescents, especially mother–daughter conflict, tends to be more intense than conflict between fathers and adolescents (Laursen & Collins, 1994; Montemayor, Eberly, & Flannery, 1993; Steinberg & Silk, 2002; compare with Robin, Koepke, & Moye, 1990). McGue et al. (2005) found that girls, in comparison with boys, reported more positive relations (including less hostile, conflictual interactions) with parents at age 11, but that this difference evaporated by age 14; thus, it is possible that reports of greater conflict for parents and daughters are partly due to the more dramatic decline in the quality of their relationship from late childhood into adolescence. However, this pattern of gender differences has not always been found and was not evident in the Laursen et al. (1998) meta-analysis.

QUALITY OF THE PARENT–ADOLESCENT CONFLICTS AND ADOLESCENTS’ SOCIOEMOTIONAL OUTCOMES

An important question for those wishing to study parent–adolescent conflict reactions is whether the degree of support, derogation, or hostility in parent–adolescent discussions when problem solving, decision making, or discussing potentially conflictual issues is related to important developmental outcomes for youth. The limited data suggest that the answer is yes, but depending on the intensity of the negativity or the quality of the ongoing relationship. High levels of parent–child conflict and negativity often have been linked to negative outcomes for youths (Forehand, Long, Brody, & Fauber, 1986; Kim et al., 2001; also see Ramos, Guerin, Gottfried, Bathurt, & Oliver, 2005), particularly when they occur within the context of contentious and hostile interchanges (Laursen & Collins, 1994; Kim et al., 2001; Steinberg & Silk, 2002). However, relations of conflict and parental negativity with negative developmental outcomes or behaviors generally are modest or nonsignificant when adolescents perceive their parents as supportive (Barrera & Stice, 1998; Galambos, Sears, Almeida, & Kolaric, 1995). In fact, it has been argued that moderate levels of parent–adolescent conflict that occur within a relationship characterized by harmony and cohesion may be associated with better adjustment than either no conflict or frequent conflict (Adams & Laursen, 2001; Cooper, 1988; Smetana et al., 2006). Moreover, the quality of the interactions during conflict interactions may be critical. As summarized by Steinberg and Silk (2002), “it may be the affective intensity of the conflict, rather than its frequency or content, that distinguishes adaptive from maladaptive parent–adolescent conflict” (p. 123).

For example, parental mutuality and relatedness during discussions that involve decision making and/or potential conflict—including behaviors that indicate support for, involvement with, and respect or validation of the other—have been positively associated with adolescents’ identity exploration, ego development (which reflects adolescents’ characteristic ways of imposing meaning upon their experiences and their relationships; Allen, Hauser, Bell, & O’Connor, 1994), and self-esteem (Allen, Hauser, Bell, & O’Connor, 1994; Grotevant & Cooper, 1985), as have adolescents’ autonomy-relatedness communications toward their parents (i.e., behavior that involves negotiating differences in opinion, interest and attention to another’s thoughts and feelings, independence of thought, and interest in, involvement in, and validation of another person’s thoughts and feelings; Allen, Hauser, Bell, & O’Connor, 1994). Supportive rather than hostile parent–adolescent interactions during problem solving or potentially contentious discussions likely foster a sense of connection between adolescents and their parents, and connection with significant adults is believed to promote positive identity development (Grotevant, 1998).

Allen also found that individual differences in autonomy-promoting and relatedness communications were associated with youths’ problem behaviors. Both parents’ and youths’ autonomy-relatedness communications when youths were age 14 (but generally not at age 16)—including expressing and discussing reasons behind disagreements, confidence in stating one’s positions, validation and agreement with another’s position, and attending to the other person’s statements—were negatively related to youths’ depressive mood at age 16 and externalizing symptoms at age 17. Adolescent-to-father and mother-to-adolescent inhibition of relatedness scores were positively related to youths’ depressed affect at age 16. In contrast, youths’ hostile and cutting off behaviors toward their mothers at age 16 predicted higher levels of externalizing problems at that age (Allen, Hauser, Eickholt, Bell, & O’Connor, 1994). Youths who were hostile toward their parent also tended to be low in autonomous relatedness in parent–adolescent discussions (Allen, Hauser, O’Connor, Bell, & Eickholt, 1996), whereas parental undermining of autonomy was linked to youths’ concurrent hostility toward their parents and hostility with peers nearly a decade later (Allen, Hauser, O’Connor, & Bell, 2002).

In brief, Allen found associations of both autonomy-promoting behavior and relatedness or hostility during family discussions with a variety of developmental outcomes. Autonomy-promoting or autonomy-inhibiting verbalizations cannot be considered equivalent to hostile parent–adolescent communications, and in Allen’s research the overt expression of hostility has not been as consistently (or uniquely; Allen et al., 1996) related to youths’ prosocial behavior or psychosocial development as have autonomy-relatedness communications.

Consistent with the findings of Allen, Hauser, Eickholt et al. (1994), Henggeler, Hanson, Borduin, Watson, and Brunk (1985) found adolescent sons’ and mothers’ supportive statements during a joint decision-making task were significantly lower for dyads in which the adolescent was a felon. Conversely, observed adolescent aggressive communications, maternal defensive communications, and reports of conflict and observed conflict tended to be higher for nonviolent felons than for control youths, whereas violent felons appeared to have low levels of all types of communication with their mothers. Adolescents’ reports of attacking versus compromising during disagreements with parents also have been positively related to concurrent reports of youths’ misconduct, depression, and distress, whereas adolescents’ reports of avoiding talking during disagreements have been positively related to youths’ concurrent depression (youth-reported) and distress (parent- and youth-reported, combined; Rubenstein & Feldman, 1993). Moreover, consistent with other research demonstrating relations between the frequency of adolescent-reported conflict with parents and concurrent externalizing problems (e.g., Barrera, Chassin, & Rogosch, 1993), Burt, McGue, Krueger, and Iacono (2005) found that a composite measure of child-reported parent–child conflict at age 11 (including frequency and intensity of conflict) predicted youths’ self-reported externalizing behavior problems 3 years later, and vice versa. In this genetically informed twin study, reported conflict predicted youths’ externalizing problems through genetic, common environmental, and unique environmental factors. Thus, the results suggested that parent–child conflict partially resulted from parents’ responses to their child’s heritable externalizing problem behavior, while simultaneously contributing to their child’s externalizing problem via environmental mechanisms. Once genetic effects were statistically controlled, parenting (as perceived by adolescents) continued to exert an environmentally mediated influence (both family-wide and child-specific) on youths’ externalizing behavior.

In summary, initial research suggests that high levels of positive affect and support, and low frequency of intense conflict and/or low levels of hostility in parent–adolescent discussions/conflict are related to higher quality socioemotional functioning in adolescents. Thus, it is important to study factors that predict individual differences in both adolescents’ and parents’ affect communications when discussing potentially conflictual issues.

CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORKS

There are several global conceptual models that seem to be particularly relevant to a discussion of normative change in parent–offspring conflict and prediction of individual differences in the quality of parent–adolescent conflict-related reactions from variables in childhood. However, relevant theories tend to differ in their emphasis on mean-level and differential continuity (e.g., De Fruyt et al., 2006). Mean-level continuity or stability refers to the extent to which the mean level of a variable is stable over time. Differential continuity refers to the degree to which relative rank–order differences among people remain invariant over time.

Especially in past decades, a quite common conceptual model has been that many aspects of adolescents’ biological and social functioning change fairly abruptly in adolescence. This perspective was partly derived from Hall’s (1904) now historic assertion that adolescence is a time of tumultuous change and stress, and partly from psychoanalytic theorists’ ideas regarding hormonal changes at puberty, resurrected oedipal feelings and conflicts (Freud, 1921/1955; see Collins & Laursen, 2004), and changes in adolescence due to ego identity development and striving for autonomy (Blos, 1979; Erikson, 1950, 1968). More recently, some researchers have viewed transitions such as adolescence as turning points that provide opportunities for the emergence of new behaviors, the discontinuation of behaviors, the alteration of behaviors, or the re-patterning of behaviors, all in response to the contextual demands brought forth by the transition points (Graber & Brooks-Gunn, 1996). Alternatively, or in addition, the changes in adolescence may be viewed as due to either relatively abrupt biological changes (e.g., puberty) that affect the social context (see Laursen et al., 1998) or changes in youths’ cognitive maturity and in social expectancies (Collins & Laursen, 2004). In addition, some theorists view adolescence as a time of transition and change for parents, who are starting to deal with limitations in their physical capacities, changes in their appearance, and often reductions in life opportunities at the same time as their children are on the threshold of life with seemingly endless choices and on the cusp of sexual and physical maturation (Silverberg & Steinberg, 1987; Steinberg & Silk, 2002; Steinberg & Steinberg, 1994).

Theorists who emphasize relatively abrupt changes in adolescence seem to focus more on mean-level stability (or the lack thereof) than differential stability because they often are interested in normative change rather than individual differences in patterns of change. They also tend to de-emphasize factors that provide continuity in functioning, and individual differences in this continuity, from childhood into adolescence. Thus, our thinking tends to be based more on models that focus primarily on differential stability.

Social Relationships Perspectives

Models of differential stability differ in the degree to which they view stability as due to stability in the quality of relationships or in characteristics of the parent or child, or in a combination of the two. One set of conceptual models focusing on the quality of relationships has been labeled as social relationships perspectives. In general, a social relationships perspective assumes that there is considerable stability in the quality of parent–child relationships and, hence, in the quality of their interactions, even as the child moves into adolescence (Collins & Laursen, 2004). Thus, youths with secure attachments and with warm, supportive relationships with their parents in childhood are expected to maintain those relations, at least to a moderate degree. In contrast, increased conflict and general deterioration of the relationship are more likely when the parent–child relationship was of poor quality in childhood, as youths express their growing dissatisfaction with how they are treated (Collins & Laursen, 2004). Consequently, from a social relationships perspective, it is likely that the degree of conflict in adolescence is related to parental supportive parenting in childhood, as well as with youths’ negativity/positivity toward, and attachment with, parents in childhood. A social relationships perspective also suggests that there is some differential stability in the general quality of the parent–child relationship, that individual differences in mean level changes from childhood to adolescence are related to earlier quality of the relationship, and that the quality of the relationship in adolescence can be predicted from a range of relationship variables assessed in childhood.

Although limited in number, findings from longitudinal research provide some support for social relationships perspectives (Collins & Laursen, 2004; Conger & Ge, 1999; Kim et al. 2001; Loeber et al., 2000). For example, researchers have found some evidence of differential stability in parental punitiveness (Eisenberg et al., 1999), aversive discipline (Vuchinich, Bank, & Patterson, 1992), positive and negative expression of emotion in the home across childhood and into early (Eisenberg et al., 2005) and mid-adolescence (Michalik et al., 2007), and in parent–adolescent conflict discussions across adolescence (Conger & Ge, 1999; Kim et al., 2001; McGue et al., 2005). Similarly, youths’ negative affect toward parents in conflict situations tends to be correlated across time (Kim et al., 2001).

There are a variety of mechanisms that could account for the differential stability of the quality of parent–child relationships, including as reflected in the quality of parent–adolescent emotional communications during potentially conflictual discussions. As already mentioned, warm supportive relationships are likely to foster a pattern of interactions in a dyad that perpetuate positive-affective communication between parent and child. Moreover, when parents are warm and sensitive with their children, their children are likely to develop secure attachments (Thompson, 2006). Children with secure attachments tend to develop working models of relationships that are positive and constructive and these models are expected to influence the quality of their relationships and emotion communication in the future (e.g., Kochanska, Aksan, & Carlson, 2005). However, the stability of attachment status over time is modest, and children tend to maintain a secure attachment primarily when the family is not overly stressed and the parent remains sensitive to the child’s needs (Thompson, 2006). Nonetheless, adolescents’ security of attachment has been positively related to observed parent–child relatedness (validating statements, displays of engagement, and empathy with the other party and their statements) when discussing a past disagreement, as well as youths’ perceptions of maternal supportiveness (Allen et al., 2003).

In adolescence and early adulthood, security of attachment (Kobak & Sceery, 1988; Mikulincer & Shaver, 2005) and parental positivity versus negativity (e.g., Eisenberg et al., 2005) have been linked to adolescents’ regulation, which would be expected to affect the quality of youths’ emotional experience and expressivity, as well as problem behaviors that involve affect regulation (e.g., externalizing and internalizing problems; Allen, Moore, Kuperminc, & Bell, 1998). Thus, the associations of relationship quality during childhood with adolescents’ later behavior with their parents, as well as parents’ reactions to their adolescents, may be partly mediated through aspects of children’s socioemotional functioning (e.g., self-regulation, proneness to negative emotion; Eisenberg, Cumberland, & Spinrad, 1998). Other mechanisms by which supportive parents may foster children’s positive expressivity are discussed shortly.

Perspectives Emphasizing Stability of Dispositional Characteristics

Whereas a social relationships perspective highlights continuity in development due to the stability of quality of relationships, the accentuation principle proposed by Elder and Caspi (1990) emphasizes continuity from childhood to adolescence due to the stability of personality and related behaviors (and could also explain mean levels of change for individuals with specific dispositions). According to Elder and Caspi (1990), adaptive responses are shaped by the requirements of new situations, but also vary based on the social and psychological resources individuals bring to new situations. They describe the accentuation principle as referring to “the increase in emphasis or salience of these already prominent characteristics during social transitions in the life course” (p. 294). Specifically, this perspective focuses on how pre-existing psychological dispositions are accentuated during times of stress and transition (such as the transition into adolescence) and foster differential continuity rather than discontinuity. The accentuation argument is that during times of challenge (such as transitions), people assimilate new experiences into their already existing behavior and coping repertoire (also see Block, 1982). Thus, for example, Elder et al. (Elder, Caspi, & Van Nguyen, 1986) found that already existing tendencies such as irritability or the tendency to explode when angered became more extreme during times of economic hardship.

Similarly, Caspi et al. (Caspi, Elder, & Bem, 1987, 1988) differentiated cumulative continuity and interactional continuity; these mechanisms are logically linked with the accentuation principle. Cumulative continuity refers to a person’s dispositionally guided selection and construction of environments; the argument is that a person’s dispositional characteristics can lead him or her to select or construct environments that reinforce and sustain those dispositions. For example, well-regulated people may select situations that provide sufficient structure or lack of distracting stimuli and thereby enhance their ability to focus attention and act in regulated ways. Caspi et al. (1987, 1988) suggested that cumulative continuity is responsible for many of the enduring individual differences across the life course.

In contrast, interactional continuity refers to continuity resulting from the reciprocal, dynamic transaction between a person and the environment. It reflects the continuing cycle of a person acting, the environment reacting, and the person reacting back. Caspi et al. argued that this general process can foster continuity through behavioral and cognitive mechanisms. They cited as examples Patterson’s (1982) research demonstrating how family interactions can sustain a destructive and aversive patterns of behavior in children, and Dodge’s work (see Dodge, Coie, & Lynam, 2006) on the tendency of aggressive children to expect others to be hostile, which leads to behavior that elicits hostility from others and sustains their own aggression. In their own work, Caspi et al. (1987, 1988) traced continuities into adulthood in the consequences of shy or ill-tempered children’s behavior and argued that these continuities were due to both the progressive accumulation of their own consequences (cumulative continuity) and the tendency to evoke maintaining responses from others during social interactions (interactional continuity). Thus, both types of continuity are grounded in dispositional continuity, although interactional continuity is due partly to the influence of social interactions. However, the notion of interactional continuity, more than a social relationships view of continuity, emphasizes how the individual’s characteristics and related behaviors elicit a pattern of social interactions that reinforces an existing pattern of functioning.

Evidence for the Stability of Temperament/Personality

Perspectives emphasizing the role of dispositional characteristics in continuity assume that there is considerable stability in aspects of personality and behavior. In fact, there is substantial differential stability in temperament and personality across childhood (e.g., De Fruyt et al., 2006; Murphy, Eisenberg, Fabes, Shepard, & Guthrie, 1999; Rothbart & Bates, 2006) and into early adolescence (De Fruyt et al., 2006; Raffaelli, Crockett, & Shen, 2005) and adulthood (Caspi et al., 1987, 1988). In a meta-analysis, Roberts and DelVecchio (2000) found that the estimated population correlation for personality from age 12 to 17.9 years was .43 (when controlling for the time interval of studies). In studies of children’s temperament before the age of 12, differential consistency was .47 (when controlling for the time interval of studies) for temperamental task persistence, .46 for negative emotionality, .51 for approach, .52 for adaptability, .49 for rhythmicity, and .35 for threshold (also see McCrae et al., 2002).

There also appears to be mean-level stability in some dispositional characteristics (i.e., personality) in adolescence and change in mean level for others; findings likely differ somewhat depending on the time frame over which stability is examined. McCrae et al. (2002) found that conscientiousness, social vitality, agreeableness, and openness were stable between ages 10 and 18, whereas emotional stability and social dominance increased across this age span. De Fruyt et al. (2006) found a small decrease in the mean level of emotional instability in early adolescence (ages 10–11 and 12–13), as well as a small increase in conscientiousness. Murphy et al. (1999) found that a decline in negative emotionality and an increase in some measures of regulation from the late preschool years to age 10–12. Using growth curves to examine change from preschool age to adolescence, Wong et al. (2006) found behavioral control (equivalent to Block and Block’s [1980] construct of ego control) increased with age and those with lower control in early childhood showed greater improvement over time. These findings suggest that self-regulation (which is linked to conscientiousness; Caspi & Shiner, 2006) and emotionality (as reflected in emotional instability) may change some in mean levels in adolescence, even though these characteristics generally show differential stability across time.

Heredity and Stability in Dispositional Characteristics and Parent–Adolescent Conflict

If, consistent with the accentuation principle, there is differential stability in personality, heredity is likely to account for some of this stability. There is considerable heritability in aspects of temperament/personality such as anger/frustration and self-regulation (e.g., Goldsmith, Buss, & Lemery, 1997; Yamagata et al., 2005), and genetic factors appear to contribute to the stability in self-regulation and emotionality over time in adolescence (De Fruyt et al., 2006). Unshared environmental factors also were found by De Fruyt et al. (2006) to contribute to this continuity, whereas shared environmental factors did not.

Moreover, genetic factors may contribute to the nature and stability of parent–adolescent conflict. In a recent study, for example, McGue et al. (2005) found that heredity accounted for more of the variance in adolescent-reported parent–child conflict at age 14 than at age 11, and that genetic effects were highly overlapping for the two ages. However, as might be expected, there were individual differences in the strength of the estimates for heritable (and environmental) effects (e.g., between girls and boys). Such findings suggest that there is considerable continuity in reported parent–adolescent conflict across early adolescence due to heredity, and that differences in characteristics with a partly heritable basis (e.g., temperament/personality) might be one factor underlying both across-time stability in parent–adolescent conflict and individual differences in the quantity and/or quality of this conflict.

Summary of the Conceptual Models

In summary, some conceptual models emphasize stability from childhood into adolescence in behavior and/or psychological functioning whereas others propose that there is relatively dramatic change. Models pertaining to abrupt change tend to focus more (but not exclusively) on mean-level, normative stability versus instability, whereas models of continuity tend to be applied mostly to the examination of differential stability. Although sometimes less explicit in this regard, the various conceptual approaches also differ in their emphasis on the degree to which individual differences in relationships or personal characteristics are likely to predict quality of parent–child conflict-related reactions in adolescence.

Our focus on factors that predict individual differences in the quality of mothers’ and adolescents’ conflict reactions seems to be most compatible with models that emphasize differential stability. Based on a social relationships perspective, one is likely to hypothesize that the quality of parents’ behaviors with their children during the first decade of life predicts the quality of parent–child interactions during adolescence. Such a finding also would not be inconsistent with the accentuation model if one assumes that children’s personalities evoke predictable kinds of responses from people in their environment (interactional continuity; Caspi et al., 1988). Based on the accentuation principle, one is most likely to hypothesize that children’s dispositional, temperamentally based characteristics during childhood predict both their own affective reactions and their parents’ reactions to them during potentially conflictual discussions in adolescence; this is because children’s personalities exhibit considerable differential stability over time and likely evoke reactions from their parents over time (e.g., Brody & Ge, 2001; Eisenberg et al., 1999). Nonetheless, such a pattern of findings would not undermine a social relationships perspective if one assumes that part of the differential stability in children’s dispositions is due to the consistency of parents’ behaviors over time and the quality of the parent–child relationships. Neither social relationships approaches nor an accentuation perspective has strong implications regarding normative mean-level stability in children’s dispositional characteristics or in parenting behaviors over time, although as already noted, they lend themselves to hypotheses regarding prediction from individual differences in patterns of change in mean level of parenting or children’s dispositional characteristics.

Although null findings are not conclusive or compelling, a lack of a relation between childhood parenting behaviors and the quality of parent–child interactions in adolescence would be inconsistent with a social relationships perspective, whereas a lack of a relation between children’s dispositional characteristics and the quality of parent–child interactions in adolescence would not support an accentuation model or a model emphasizing continuity due to genetic contributions to temperament/personality or parenting. Although the accentuation model focuses on times of stress, the underlying assumption is one of personality continuity. Moreover, if childhood measures of youths’ dispositional characteristics and of parenting behaviors did not predict the quality of conflict-related interactions during adolescence, but concurrent adolescent indices of these constructs did, then the data would support a more discontinuous model in which contemporaneous variables, rather than prior parenting or child dispositions are important potential causal factors. In the present study, we hypothesized that adolescents’ and parents’ conflict behaviors would be predicted by both childhood and concurrent parenting and child dispositions (and related problem behaviors), a pattern that would be consistent with social relationships and accentuation models.

PREDICTION OF THE QUALITY OF PARENT–CHILD INTERACTION FROM PARENTING: EMPIRICAL FINDINGS

As previously discussed, based on a social relationships perspective, an obvious candidate for the prediction of individual differences in parents’ and adolescents’ conflict reactions is parental socialization-relevant variables. According to a social relationships perspective, a poor quality parent–child relationship, based in part on hostile, nonsupportive, or otherwise inadequate parenting, is likely to exhibit continuity across childhood and to contribute to later conflicted interactions and relationships. Research on relations of youths’ and parents’ conflict reactions to parenting disciplinary/teaching practices, parents’ affect in the home and/or with their children, and the quality of the parent–child relationship is now reviewed.

Youths’ Reactions to Their Parents

Prior research suggests that parental behavior is likely to predict the quality of youths’ affective reactions and emotion-related behavior in interactions with parents. This pattern of association likely begins in early childhood; parents’ insensitive, hostile, and negative responses to young children tend to be related to children’s anger during family interactions (Conger, Neppl, Kim, & Scarmella, 2003; Snyder, Stoolmiller, Wilson, & Yamamoto, 2003). Conversely, when mothers express positive affect with their preschool children, their children are likely to respond in a positive manner (Kochanska, 1997).

In studies of adolescents, the quality of parenting or the parent–child relationship also has been associated with conflict-related behaviors. For example, Capaldi, Forgatch, and Crosby (1994) found that 8th-grade sons’ hostility during the discussion of conflictual issues was negatively related to a high-quality parent–son relationship (as well as perceptions of adequate problem solving), whereas sons’ humor was positively related. Capaldi et al. (1994) did not, however, examine the prediction of conflict reactions from parent behaviors assessed at an earlier time. Rubenstein and Feldman (1993) found that adolescents’ reports of attacking their parents during a disagreement (e.g., expressing anger, sarcasm, or throwing something) were related to their earlier reports of parental rejection (but not family supportiveness), whereas family supportiveness (assessed with ratings and observations) was related to adolescents’ reports of trying to compromise with parents and low avoidance of talking or holding in feelings during disagreements. Similarly, Allen et al. (2003) found that a dyadic measure of mother–adolescent relatedness during the discussion of conflictual issues was positively related to youths’ concurrent reports of mothers’ supportiveness outside the conflict context. In addition, Yau and Smetana (1996) found that low parental warmth was related to more conflict between Chinese adolescents and their parents (also see Smetana, 1996; contrast with Campione-Barr & Smetana, 2004, and Smetana, Metzger, & Campione-Barr, 2004).

In one of the few longitudinal studies on this issue, Kim et al. (2001) found that both parents’ and adolescents’ initial levels of negative emotion toward one another predicted the rates of growth and change in their expressed negative affect. Thus, parents’ emotion predicted adolescents’ emotion with their parents over time, but this relation was reciprocal. In addition, Overbeek, Stattin, Vermulst, Ha, and Engels (2007) found that a positive parent–child relationship in childhood predicted reported parent–child conflict in adolescence. In contrast, in a study of African American families, Campione-Barr and Smetana (2004) did not find the degree of support when discussing a conflictual issue predicted parent- or adolescent-reported conflict intensity approximately 2 years later. Thus, in general, there seems to be a relation between the quality of affect expressed during conflicts or the amount of parent–child conflict and measures of quality of parenting, although relatively few of the findings are based on longitudinal data and the findings are sometimes inconsistent.

Findings of relations between the quality of the parent–child relationship and parent–child conflict-relevant behavior are congruent with the relations found between high parental expression of negative or positive emotion in the family and children’s expression of analogous emotion (with the association apparently increasing with age for negative parental expressivity; Halberstadt, Crisp, & Eaton, 1999). Also relevant is the finding that harsh parent-reported reactions to children’s expression of negative emotion were related to high levels of children’s externalizing emotions such as hostility (Eisenberg et al., 1999). In addition to hereditary factors that produce similarity between parents’ and children’s dispositional emotionality, it is likely that children model their parents’ emotional expressivity and reactions to others’ emotions.

Possible mediators of the relation between quality of parenting and children’s affectivity in the family and with parents (including during conflict) include children’s emotion understanding, negative emotionality, and emotion regulation. Supportive parents, and parents who tend to have positive relationships with their children, tend to take the time to teach children about emotions (including linking them to the child’s own experience) and to elaborate on emotions in discussions (Eisenberg, Losoya, et al., 2001; Farrar, Fasig, & Welch-Ross, 1997; Laible, 2004b; Laible & Thompson, 2000; Reese, 2002; Thompson, 2006). Thus, it is not surprising that warm, supportive parenting has been associated with children’s understanding of others’ emotions (Denham, 1998; Laible & Thompson, 1998; Ontai & Thompson, 2002; Thompson, 2006), as well as with children’s self-regulation (Brody & Ge, 2001; Eisenberg, Gershoff, et al., 2001; Eisenberg et al., 2005), both of which predict children’s emotional and social competence (Eisenberg, Gershoff, et al., 2001; Halberstadt et al., 1999; McDowell & Parke, 2005; see Parke & Buriel, 2006). Similarly, mothers’ mitigation and resolution of conflicts with young children—modes of positive parenting—predict children’s emotion understanding and prosocial behavior (Laible & Thompson, 2002). Moreover, there is mounting evidence, albeit mostly from studies of young children, that parents’ discussion of emotion in the family or with the child is associated with children’s subsequent understanding of emotion (Laible, 2004a, b; Thompson, 2006) and children’s self-regulation (Gottman, Katz, & Hooven, 1997).

Despite strong conceptual reasons to expect parents’ concurrent and prior parenting behaviors to be related to adolescents’ emotional reactions during the discussion of conflictual issues, there are few longitudinal studies in which the quality of parent–child affective exchanges has been predicted from parenting behaviors years earlier. In addition, with a few exceptions (e.g., Capaldi et al., 1994; Conger & Ge, 1999; Kim et al., 2001; Vuchinich, Angelelli, & Gatherum, 1996), parents’ and youths’ positive emotional reactions during conflicts have not been examined in relation to either concurrent or prior parenting behaviors. Based on the existing theory and on empirical findings (mostly from studies of younger children), it is reasonable to expect parents’ supportive reactions and attempts to help their children to understand emotion, and perhaps increases (and less of a decline) in supportive parenting, to be associated with youths’ regulated and relatively nonhostile responses to parents when discussing a conflictual issue.

Parents’ Reactions to Their Adolescents

It is logical to expect measures of parents’ prior parenting behaviors to predict not only their children’s conflict reactions, but also their own reactions to their adolescent. As already noted, parents’ expressivity and hostility versus warmth with their children tend to be somewhat stable overtime (Conger & Ge, 1999; Eisenberg et al., 1999), likely due to the influence of both parental heredity, prior learning, and the stability of children’s characteristics and behaviors (see McGue et al., 2005). Indeed, negative or hostile parenting predicts the likelihood of similar parenting over time, whereas positive parenting predicts the continuity and growth of this type of parenting (Kim et al., 2001; McGue et al., 2005).

This continuity in hostile/punitive versus supportive parenting is likely to impact the quality of parents’ relationships with their children and, hence, their behavior in conflictual contexts with their adolescent offspring. Some of the researchers already cited found that the quality of the parent–child relationship was associated with the parents’ reactions during conflicts or with the degree to which conflict was intense (e.g., Allen et al., 2003; Smetana, 1996), which in turn would be expected to affect the ongoing parent–child relationship. Intensity of mother–child conflict also has been negatively related to mothers’ sense of well-being (Silverberg & Steinberg, 1987); consequently, parent–child conflict may reduce mothers’ psychological resources and undermine the quality of their parenting. Punitive and hostile parental behaviors are likely to foster a cycle of hostility and anger between parent and child (Brody & Ge, 2001; Conger & Ge, 1999; Eisenberg et al., 1999; Kim et al., 2001), undercutting feelings of attachment and trust. For example, Capaldi et al. (1994) found that mothers’ and fathers’ hostility when discussing high-conflict family issues were negatively related to a composite index of quality of the parent–adolescent son relationship, whereas humor and/or affection was positively related.

A hostile and eroding parent–child relationship is likely to affect the future quality of parenting—including parents’ conflict reactions—for multiple reasons. Children are less likely to comply (Kochanska & Aksan, 1995) or to attend to (Hoffman, 2000) the expectations of hostile, negative parents, which would be expected to exacerbate parents’ hostility and tendencies to react in a controlling and hostile or punitive manner. Moreover, interactions between parents and youths that are low in warmth/support and are coercive are associated with difficulties in family members’ problem solving (Vuchinich et al., 1996; also see Kobak, Cole, Ferenz-Gillies, & Fleming, 1993), which in turn predict high levels of parent–adolescent disagreement (Rueter & Conger, 1995a) and adolescents’ problem behavior (Coughlin & Vuchinich, 1996; Robin et al., 1990; Vuchinich, Wood, & Vuchinich, 1994; also see Dubow, Tisak, Causey, Hryshko, & Reid, 1991). The quality of the parent–child relationship and interactions has been linked to youths’ adjustment (Rueter & Conger, 1998; Soenens, Vansteenkiste, Luyckx, & Goossens, 2006; Vuchinich et al., 1992; see Collins & Steinberg, 2006), and it is likely that problems in children’s adjustment further evoke negative parenting and increases in parental hostility during conflict interactions (Patterson, 1982; see Dodge et al., 2006).

Thus, there likely is an escalating cycle of negative parenting that is linked to deteriorating parent–child relationships, problems in family problem solving, and associated problems in adolescents’ adjustment. However, with the exception of the work of Conger or Vuchinich and their colleagues, there are few studies examining parenting behavior as a longitudinal predictor of parental (or adolescent) negativity during conflicts, and to our knowledge, none has examined quality of parenting before the children were age 11 or 12. As noted by Conger and Ge (1999), there is a need to study relations between parenting in childhood and parents’ and youths’ hostility and warmth with one another in adolescence.

DISPOSITIONAL CORRELATES OF PARENT–ADOLESCENT CONFLICT REACTIONS

In accordance with theories predicting that consistency in personality partly accounts for later social behavior during developmental transitions (e.g., Block, 1982), we expected that adolescents’ personality/temperamental characteristics in childhood and in adolescence to predict both their own and their mothers’ conflict reactions. In this study, we examined relations of adolescents’ and their parents’ conflict reactions with youths’ self-control/regulation, personality resiliency, and negative emotionality. We label such characteristics “dispositional” in the recognition that they can be considered aspects of temperament and/or personality (Caspi & Shiner, 2006; Rothbart & Bates, 2006). In addition, we examined the relation of conflict reactions to children’s externalizing behaviors, which themselves have been empirically associated with dispositional negative emotionality and lack of regulation (see Dodge et al., 2006; Eisenberg, Fabes, Guthrie, & Reiser, 2000; Eisenberg, Cumberland et al., 2001).

Dispositional Regulation, Control, Resiliency, and Negative Emotionality: The Constructs

Regulatory and control processes, as well as the predisposition to experience negative emotions, are viewed as having a temperamental basis and as part of personality (Caspi & Shiner, 2006; Rothbart & Bates, 2006). Rothbart and Bates (2006) defined temperament as “constitutionally based individual difference in reactivity and self-regulation, in the domains of affect, activity, and attention. … By the term constitutional, we refer to the biological bases of temperament, influenced over time by heredity, maturation, and experience” (p. 100). In contemporary writings, distinctions between temperament and personality are breaking down, with temperament being viewed as relatively narrow, lower levels traits that contribute to personality, and personality as “including a wider range of individual differences in feeling, thinking, and behavior than in temperament” (Caspi & Shiner, 2006, p. 303). Although some researchers explicitly discuss temperament in late childhood or adolescence (e.g., Capaldi & Rothbart, 1992; Shiner, 1998), many researchers examining dispositional proclivities in adolescence label them as personality or simply focus on the specific characteristics or behaviors without labeling them as temperament or personality (see Caspi & Shiner, 2006).

In Rothbart’s model (Rothbart & Bates, 2006), temperament is viewed as involving two major domains, reactivity and self-regulation. According to Rothbart and Bates, reactivity “refers to responsiveness to change in the external and internal environment. Reactivity includes a broad range of reactions (e.g., the emotions of fear, cardiac reactivity) and more general tendencies (e.g., negative emotionality) ….” (p. 100). Reactivity also includes action tendencies such as freezing, attack, and/or inhibition associated with emotion. Rothbart’s construct of effortful control, which is intimately involved in self-regulation, is defined as “the efficiency of executive attention—including the ability to inhibit a dominant response and/or to activate a subdominant response, to plan, and to detect errors” (Rothbart & Bates, 2006, p. 129). It includes the abilities to willfully modulate (e.g., focus, shift) attention as needed (i.e., attention shifting and focusing), as well as the abilities to willfully inhibit and activate behavior when needed, even if the individual prefers not to do so (i.e., labeled inhibitory and activational control, respectively). Individual differences in effortful control are moderately stable across childhood and into adolescence (e.g., Eisenberg et al., 2005; Murphy et al., 1999).

Block and Block discussed a construct related to effortful control—ego control—which is defined as the “threshold or operating characteristic of an individual with regard to the expression or containment of impulses, feelings, and desires” (1980, p. 43). Ego undercontrol involves insufficient modulation of impulses, the inability to delay gratification, immediate and direct expression of motivations and affect, and vulnerability to environmental distractors. Conversely, ego overcontrol refers to the containment of impulses, delay of gratification, inhibition of actions and affect, and insulation from environmental distractors. Many measures of ego control likely include elements of both reactivity (e.g., inhibition; Derryberry & Rothbart, 1997) and effortful control (Eisenberg & Morris, 2002; Derryberry & Rothbart, 1997). Regardless, measures of ego control typically tap over- versus undercontrol of behavior and tend to be moderately to substantially related with effortful control (e.g., Eisenberg et al., 2004). Like effortful control, measures of ego control (including impulsive undercontrol) exhibit correlational consistency across time (Block & Block, 2006; Murphy et al., 1999; Valiente et al., 2003).

Personality resiliency, another construct assessed in this study, is what Block and Block (1980) labeled as ego resiliency: “the dynamic capacity of an individual to modify his/her modal level of ego-control, in either direction, as a function of the demand characteristics of the environmental context” (p. 48). According to Block and Block (1980), high resilience involves resourceful adaptation to changing circumstances and flexible use of problem-solving strategies; low resilience involves little adaptive flexibility, an inability to respond to changing circumstances, the tendency to perseverate or become disorganized when dealing with change or stress, and difficulty recouping after traumatic experiences.

Ego resiliency (henceforth labeled resiliency for brevity and to avoid reference to psychodynamic terminology) is generally viewed as an aspect of personality (Block & Block, 1980) with a temperamental basis (Derryberry & Rothbart, 1997; Eisenberg et al., 2004). Effortful control tends to be positively related to resiliency (Eisenberg, Spinrad, & Morris, 2002; Spinrad et al., 2006), which is not surprising because children high in effortful control would be expected to have the ability to modulate their attention and behavior in a flexible manner. The relation of resiliency to ego control may be quadratic, such that moderate levels of ego control are most highly linked to resiliency (Eisenberg, Guthrie, et al., 1997; Wong et al., 2006). In structural equation models (SEMs), resiliency and effortful control are separate latent constructs (e.g., Eisenberg et al., 2004; Eisenberg, Valiente et al., 2003). Evidence of differential stability of resilience is modest and considerably weaker than that for effortful control and ego control in childhood (e.g., Eisenberg et al., 2004) and into early adolescence (Eisenberg, Valiente, et al., 2003). Using a somewhat more broadly operationalized measure of ego resiliency than Eisenberg, Block and Block (2006) found that it exhibited differential stability from preschool age until age 23 for boys. For girls, there was stability from age 7 to 11, and from 11 through adolescence. In a recent study, mean levels of resiliency did not change with age from preschool to adolescence (Wong et al., 2006).

Individual differences in negative emotionality, like effortful control, are clearly a part of temperament and personality, have a biological basis, and are relatively consistent across childhood and into early adolescence (e.g., Caspi, Henry, McGee, Moffitt, & Silva, 1995; Caspi & Silva, 1995; Lerner, Hertzog, Hooker, Hassibi, & Thomas, 1988; Murphy et al., 1999; Plomin & Stocker, 1989). However, relatively few investigators have examined the relation of dispositional negative emotionality in childhood to negative emotions expressed with parents in adolescence. Rather, the focus in the adolescent research has often been on mean-level change in children’s experience or expression of negative emotionality as the child moves into adolescence (e.g., Larson & Lampman-Petraitis, 1989) or on negative emotion exhibited with family members in adolescence (e.g., Larson et al., 1996).

Relations of Youths’ and Parents’ Conflict Reactions to Children’s Concurrent and Prior Dispositional Characteristics

Adolescents who are unregulated and prone to experience negative emotions—especially intense ones such as anger—would be expected to lose control and express relatively high levels of hostility in conflict-related interactions with their parents. This is because they are likely to have a relatively low threshold in regard to hostility/anger and more difficulty appropriately modulating the experience and expression of such negative emotions when they do occur. Clearly, unregulated children and those prone to negative emotions exhibit less socially competent behavior than their more regulated peers and are prone to behavioral problems (see Eisenberg et al. 2000, and Eisenberg & Fabes, 2006, for reviews). In addition, children’s effortful regulation has been associated with relatively constructive coping with real-life negative emotion (Eisenberg, Fabes, Nyman, Bernzweig, & Pinuelas, 1994). Similarly, almost by definition, resilient youths, in comparison to less resilient youths, would be expected to modulate aversive bouts of negative emotion and to more readily maintain (or recover) positive emotion. As has been found for effortful control, resiliency has been associated with both low levels of problem behaviors (especially internalizing problem behaviors) and high social competence (e.g., Block & Block, 1980; Block & Kremen, 1996; Eisenberg et al., 2000, 2004; Huey & Weisz, 1997; Wong et al., 2006; also see Asendorpf & van Aken, 1999; Hart, Atkins, & Fegley, 2003; Robins, John, Caspi, Moffitt, & Stouthamer-Loeber, 1996).

Given the differential stability of dispositional constructs such as control/regulation, resiliency, and negative emotionality across time, it is reasonable to expect their levels in childhood, and change in level over time, to predict adolescents’ hostile and positive conflict reactions (especially the former) with their parents. Furthermore, concurrent levels of dispositional control/regulation and negative emotionality logically should be especially related to adolescents’ conflict discussion reactions.

It is also logical to expect parents to react to youths’ temperamentally based characteristics, such that they are likely to be more hostile and less positive and supportive with children who are unregulated, prone to negative emotion, and low in resilience. Eisenberg et al. (1999) found a negative relation between children’s level of effortful control and parents’ subsequent reported punitive reactions to their children’s expression of negative emotion. Similarly, Brody and Ge (2001) found that early adolescents’ self-regulation predicted their parents’ nurturant-responsive parenting a year later. Because externalizing problem behaviors are substantially associated with temperamental/personality characteristics (Caspi & Shiner, 2006; Dodge et al., 2006; Miller & Lynam, 2001), parents’ conflict reactions may partly be a response to the problem behaviors associated with children’s dispositional characteristics (Burt et al., 2005; also see Stice & Barrera, 1995).

Empirical research dealing explicitly with the relation of youths’ temperamentally based characteristics to adolescents’ and their parents’ conflict-related reactions is sparse. In one of the few relevant studies, Rubenstein and Feldman (1993) asked adolescent males to report the degree to which they used attack (e.g., yelling, using sarcasm, saying or doing something to hurt their feelings), compromise (e.g., trying to reason, listen, or understand the parent, trying to work out a compromise), or avoidant (e.g., avoiding talking, holding feelings inside) strategies when they disagreed with a parent about something important to them. Boys’ reported use of attack strategies was related to their self-reported proneness to distress (anxiety, depression, low self-esteem, low emotional well-being) and low levels of restraint (suppression of aggression and anger, consideration of others, impulsive control, and responsibility). In addition, youth-reported avoidance during parent–child conflicts was related to high distress 4 years earlier, whereas the use of compromise was related to high restraint 4 years before. Thus, Rubenstein and Feldman found longitudinal support for the hypothesis that adolescents’ temperament/personality was related to their reactions to parents during conflict. However, their measure of restraint tapped sociomoral and nonaggressive behavior associated with self-regulation (responsibility, suppression of aggression, consideration of others) more than self-regulation per se or its temperamental bases (e.g., effortful control). In addition, the data for youths’ personality and conflict reactions were both self-reported and, thus, associations between the two might partly reflect reporter biases.

Other researchers have examined the relations of youths’ temperament to frequency of reported parent–child conflict (rather than conflict reactions). Galambos and Turner (1999) found that low adolescent temperamental adaptability (a construct conceptually related to resiliency) was associated with high adolescent-reported conflict (frequency and intensity combined) with parents, especially if fathers were also low in adaptability. Adolescents’ activity level was positively related to mothers’ reports of conflict if mothers were low in adaptability. Galambos and Turner reported some additional complex relations between youths’ and parents’ temperament and reported parent–adolescent conflict, but the results varied considerably with the reporter of conflict and sex of the child. In a somewhat similar study, Kawaguchi, Welsh, Powers, and Rostosky (1998) found that 14–18-year-old boys’ self-reported difficult temperament and relatively negative mood were positively related to the level of conflict (but not support) they perceived with their mothers, but not with their fathers. Girls’ self-reported difficult temperament was associated with less support from fathers, but temperament was not related to girls’ reports of conflict with parents.

Numerous other investigators have examined relations of children’s temperament to the quality of the parent–child relationship, but have not focused explicitly on conflict. For example, Windle (1991) found adolescents with a difficult temperament perceived lower levels of parent support. Feldman, Rubenstein, and Rubin (1988) reported that sixth graders’ self-reported restraint was related to their reports of better communication with their mother and family cohesion (i.e., emotional bonding among family members). Stoneman, Brody, and Burke (1989) found that parents’ ratings of their 7–9-year-old daughters’ (but not sons’) challenging temperament (active, prone to negative emotion, short attention span, and difficult to distract) were related to mothers’ and fathers’ reports of a less positive family emotional climate and lower affection in the family. In numerous other studies, some already cited (e.g., Gottman et al., 1997; Valiente et al., 2006), parents’ expression of emotion in the home or in response to children’s emotions and/or parental discussion of emotion have been associated with children’s temperamentally based regulation.

Although children’s and adolescents’ temperamentally based displays of emotion may affect the quality of their interactions with their parents (Cook, Kenny, & Goldstein, 1991), some data indicate that parenting practices or beliefs and parent–child closeness may also predict change in children’s temperament (Belsky, Fish, & Isabella, 1991; Bezirganian & Cohen, 1992; Eisenberg et al., 1999; Kiang, Moreno, & Robinson, 2004). And parenting, including parenting behavior during conflicts, may also predict youths’ dispositions over time, which in turn might affect the quality of subsequent parent–child conflict reactions. Consistent with this view, Best, Hauser, and Allen (1997) found that parental encouragement of youths’ autonomy/relatedness (e.g., expressing and discussing reasons for disagreements, validation of the other’s position, attention to other’s speech) when asked to resolve a dilemma and when discussing disagreements was positively related to youths’ ego resiliency in early adulthood. Thus, children’s dispositions and parenting may mutually affect one another over time, and in combination affect the quality of parent–adolescent reactions when dealing with conflicts. The nature of the relation between children’s dispositions and parenting likely depends on the facet of temperament and other variables (see Paulussen-Hoogeboom, Stams, Hermanns, & Peetsma, 2007).

SEX DIFFERENCES IN CONFLICT-RELATED REACTIONS

There are both conceptual and empirical reasons to believe that there are some sex differences in the intensity, frequency, and correlates of parents’ and adolescents’ conflict-related reactions. For example, numerous theorists have talked about the need for adolescents to develop a sense of autonomy from their parents (Allen et al., 1996; Grotevant, 1998), which could sometimes lead to conflict between adolescents and their parents. This process may be especially true and normative for daughters, who, compared with sons, tend to have relatively intense relationships with their mothers (Steinberg, 1987) and who, from a psychodynamic perspective, have been viewed as especially involved in the process of differentiating themselves from their mothers (Blos, 1979; Josselson, 1980; Graber & Brooks-Gunn, 1999).

In fact, there is fairly consistent evidence that adolescent daughters are more likely than sons to report conflicts with their mothers (Laursen, 1995; Smetana, 1989), although this has not always been found (Kawaguchi et al., 1998). Laursen (2005) reported that adolescent females reported not only more disagreements than sons with mothers but also more negative affect in disagreements with both mothers and fathers. Moreover, Conger and Ge (1999) found that adolescent girls showed greater hostility toward parents than did adolescent boys. McGue et al. (2005) did not find a higher level of conflict with parents reported by adolescent daughters than sons; however, daughters’ reports of conflict increased more than sons’ between age 11 and 14 years. This pattern of increasing conflict may create the perception that daughters and parents engage in more conflicts during adolescence than do sons.

Perhaps there are also more occasions for prolonged parent–daughter conflict in adolescence. In a study of parent–adolescent discussion of differences of opinion (Hauser et al., 1987), daughters spoke more frequently than sons, which may provide more opportunities for conflict and angry or hostile exchanges between parent and adolescent. However, these same investigators reported relatively few sex differences in youths’ reactions to their parents during a variety of family discussion tasks. One reason that sons may report or exhibit less conflict-related anger is that their conflicts with parents are more often left unresolved (Smetana, Yau, & Hanson, 1991), perhaps due to sons’ avoidance. Another is that the likelihood of girls taking their parents’ conventional perspective on conflict issues declines as they move from preadolescence into adolescence, whereas the trajectory is stable for sons (Smetana, 1989).

Although one might expect parent–adolescent interactions when dealing with disagreements/problem solving to differ for sons and daughters, the data pertaining to this issue are mixed. Flannery, Montemayor, Eberly, and Torquati (1993) found that sons, compared with daughters, expressed more neutral and less positive affect in positive and conflictual (combined) interactions with parents. Vuchinich et al. (1996) found less positive behavior during problem solving in families with young adolescent daughters in comparison with sons, although there was no difference in the quality of problem solving. In contrast, Galambos and Almeida (1992) found little evidence of sex of adolescent effects in regard to parent- or adolescent-reported level of conflict. In other studies, the sample sizes were so small that sex differences were either not examined or not found, perhaps due to lack of power (e.g., Allen et al., 1996).

Even if there were no mean sex differences in the level of conflict or intensity of affect during conflict, the predictors or correlates of affective reactions during conflicts may differ for adolescent sons and daughters or their parents. For example, Galambos et al. (1995) found positive relations of reported parent–child conflict with youths’ problem behavior for both sexes, but an association between conflict and having deviant peers was found only for male adolescents.

Galambos and Turner (1999) also found sex differences in the association between adolescents’ temperament and conflict in parent–adolescent relationships. Daughters who were relatively low in adaptable temperament were more likely to perceive conflict with parents, especially if their fathers were also low in adaptable temperament. Mothers’ perceptions of conflict with sons were highest when sons were low in activity and the mothers were low in adaptability (Galambos & Turner, 1999; also see Kawaguchi et al., 1998). Such complex interactions suggest that youths’ sex may moderate some relations of parenting or child temperament/personality to parents’ or children’s affective conflict reactions.

In summary, it appears that there may be some sex differences in parent–adolescent conflict reactions. However, it is unclear if youths’ dispositional characteristics would be expected to relate to conflict reactions more strongly for one sex or the other; in relevant studies, findings have been complex or mixed (e.g., Galambos & Turner, 1999; Kawaguchi et al., 1998). Similarly, there are no strong conceptual or empirical reasons to expect socialization-relevant behaviors to relate differently to boys’ and girls’ conflict reactions, although some parenting behaviors such as parental expression of emotion seem to predict emotion-related outcomes (e.g., empathy-related responding) for daughters more often than sons (Eisenberg et al., 1991, 1992). If adolescent daughters’ relationships with their primary caregivers (usually mothers) are more intense than those of sons and were closer in childhood (McGue et al., 2005), one might expect parents’ socialization-relevant behaviors, both concurrent and in the past, to be more strongly and consistently related to daughters’ than to sons’ reactions to parents during conflicts. Alternatively, if relations with daughters change more than those with sons in terms of intensity in early adolescence (as some have argued; e.g., Steinberg & Hill, 1978; see McGue et al., 2005), relations between parent–daughter conflict reactions and parents’ socialization-relevant behavior might be relatively strong only for concurrent measures of the latter. Because of the lack of strong compelling theory or empirical data, the direction of any sex differences in the correlates of parents’ and adolescents’ conflict reactions was difficult to predict.

THE PRESENT STUDY

Building upon the previously reviewed literature, the purpose of the present study was to examine predictors and correlates of adolescents’ and mothers’ verbal and nonverbal emotional reactions to one another when discussing conflictual issues. In particular, we were interested in two types of predictors/correlates: youths’ dispositional characteristics (control/regulation, resiliency, and negative emotionality) or related behaviors (externalizing problems) and parents’ socialization-related behaviors (e.g., warmth, discussion of emotion, affect expressed in the home and when with the child; henceforth labeled as parenting or socialization variables for brevity). These two types of variables were assessed concurrently and/or approximately 2 and 4 years earlier. In addition, we were interested in whether proximal variables such as the intensity of conflicts in the recent past, the adolescents’ negative affect and regulation when alone shortly before the conflict interaction, and the affective quality of mother–adolescent interaction shortly before the conflict discussion were related to conflict reactions, as well as whether the quality of conflict reactions predicted parents’ and youths’ satisfaction with their discussion.

Our sample was from a longitudinal study that had been assessed several times in childhood (2 years apart), as well as once in adolescence. Data from the second, third, and fourth assessments were used in this paper; data from the first assessment were not included because we did not collect parenting variables or some of the dispositional variables at the first assessment. At the fourth assessment, adolescents and mothers were observed in the laboratory when they were asked to discuss issues that had been topics of conflict between them. Nonverbal and verbal reactions, positive and negative, were coded for both mothers and adolescents. Children’s control/regulation, negative emotionality, and resiliency were reported by parents and teachers in childhood and adolescence and some observational data (on negative emotionality and regulation) were obtained during adolescence. Parenting behaviors were assessed with both parents’ reports of positive and negative expressivity in the family and observations of parent–child interactions (once at each assessment, in addition to the conflict interaction). Parents and adolescents also reported on recent conflict in the home and evaluated the quality of the conflict discussion when it was concluded. Data on variables such as age, as well as past and concurrent levels of adolescents’ externalizing problems, were also obtained. Externalizing problems do not clearly index dispositional characteristics or parenting but likely reflect the influence of both (Caspi & Shiner, 2006; Dodge et al., 2006).

Our major hypotheses concerned the relations of the adolescents’ dispositional characteristics and the parenting variables to both mothers’ and adolescents’ conflict reactions. Because we hypothesized that both constitutionally based characteristics of youths and their home environments are related to the quality of mother–adolescent relationships and interactions, and based on the notion that social relationships are somewhat stable from childhood into adolescence, we expected childhood assessments of both types of variables to predict mothers’ and adolescents’ reactions during the conflict discussion. However, because both youths’ dispositions and parenting change somewhat as children age and in response to contextual factors, we expect these associations to be relatively modest. In addition, we expected concurrent measures of youths’ dispositional characteristics and parenting to be relatively consistently related to the quality of conflict interactions because of their proximity in time and their relevance to contemporaneous mother–adolescent conflict.