If there were a prize for the most inappropriate analytical technique in dementia research, “last observation carried forward” would be the runaway winner. As a society, we have spent millions of dollars on drug research in the hope of improving the care of the estimated 24.3 million people who have dementia worldwide. Researchers, patients and families have dedicated countless hours to carrying out trials to test the efficacy of drugs to treat dementia. We then take this invaluable data and, in accordance with US Food and Drug Administration regulation, subject it to last observation carried forward, a form of analysis that introduces bias.

What is “last observation carried forward”?

Drug trials are designed to follow patients over time to determine the effect of the study drug. Participants often drop out before study completion. If these dropouts are not included in analyses, randomized trials can generate false results. Consequently, intention-to-treat analysis — the inclusion of all participants in the analysis according to the group determined at randomization — has become the standard for controlled trials. As part of this analysis, methods are used to estimate the missing data for patients who have dropped out.1

One such method is “last observation carried forward.” This technique replaces a participant's missing values after dropout with the last available measurement and assumes that the participant's responses (e.g., outcome measures) would have been stable from the point of dropout to trial completion, rather than declining or improving further. It also assumes that missing values are “missing completely at random” (i.e., that the probability of dropout is not related to variables such as disease severity, symptoms, group assignment or drug side effects).2–4

Inappropriate use in drug trials in dementia research

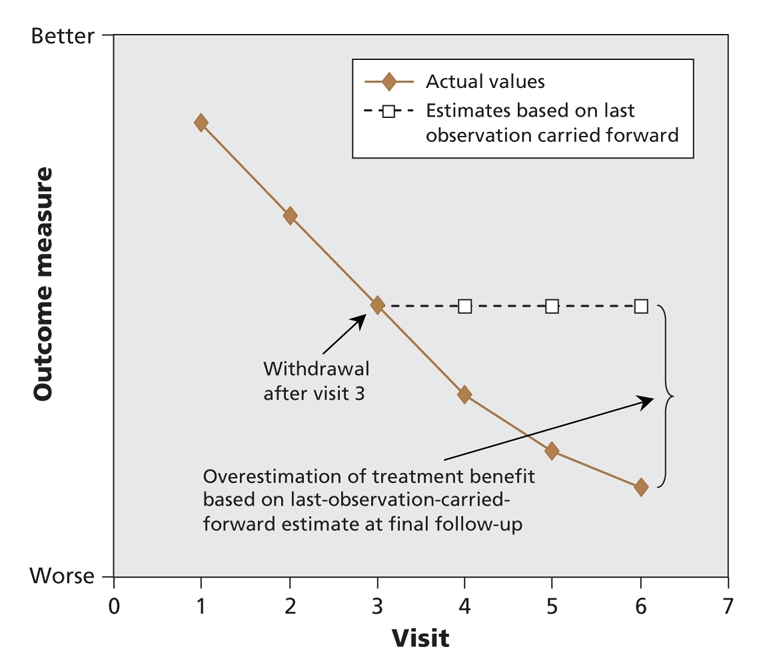

Several researchers5–11 and a committee of the European Agency for the Evaluation of Medicinal Products, the European Union counterpart of the US Food and Drug Administration,12 have raised concerns regarding the use of the last observation carried forward in dementia research. Because disease progression, a defining feature of dementia, is commonly demonstrated in graphs of outcome measures in reports of drug trials in dementia research, the primary assumption for the use of last observation carried forward (i.e., a halting of progression after dropout) is clearly violated. Last observation carried forward ignores whether the participant's condition was improving or deteriorating at the time of dropout but instead freezes outcomes at the value observed before dropout (i.e., last observation) thereby inappropriately stopping decline in outcome measures and artificially stabilizing disease in dropouts (Figure 1).13 If there are more dropouts in the treatment group than in the control group, such an approach to analysis will bias results in favour of the study drug, since a greater proportion of patients in the treatment group will have their decline artificially stabilized at an earlier stage of disease.

Figure 1: Potential impact of last-observation-carried-forward analysis in longitudinal randomized controlled trials in chronic progressive diseases.

The argument that results of analyses using last observation carried forward are correct because they are supported by the results of observed case analysis, completer analysis, fully evaluable population analysis, or treated per protocol analysis is questionable, if not completely false. These techniques exclude participants with missing data from the analysis and are therefore not intention-to-treat analyses. Many, if not all, of these analyses will be biased in the same direction as last observation carried forward and do not represent valid confirmatory analyses.

Other forms of intention-to-treat analysis would not cost anything to perform and are readily available in standard statistical programs. These can be as simple as using the rate of decline noted in the control group and applying it to all dropouts. The study on mild cognitive impairment by Petersen and colleagues14 is a model for future research, because the authors used sensitivity analyses of various intention-to-treat approaches.

How serious is this problem?

Last observation carried forward is the technique most commonly used in intention-to-treat analyses in trials of dementia drugs. The studies using this technique frequently show higher dropout rates in the treatment group than in the control group (a factor that will bias results in favour of the treatment) and rarely verify results with other intention-to-treat analyses. Consequently, although there is a preponderance of evidence suggesting dementia drugs have some degree of effect in some patients, we do not know their true effectiveness. Without confirmatory intention-to-treat sensitivity analyses, the worst-case scenario of false-positive trial results cannot be confidently excluded. Guidelines, such as those of the Canadian Consensus Conference on the Diagnosis and Treatment of Dementia, are forced to base their recommendations on a body of research that likely includes exaggerated or potentially false results. At the end of the day, the burden of proof rests with investigators to show that results based on last observation carried forward are not biased by verifying them with alternate intention-to-treat analyses. Only a minority of investigators do so.

These concerns seem particularly relevant to trials of cholinesterase inhibitors. In these trials, dropout rates are often higher in treatment groups than in control groups. Also, the assumption that missing values are “missing completely at random” is unlikely given the frequently reported gastrointestinal side effects of the cholinesterase inhibitors.

Memantine appears to have fewer side effects than cholinesterase inhibitors. Consequently, the number of dropouts in memantine treatment groups is often similar to or less than the number in placebo groups. Since the bias from last observation carried forward favours more toxic therapies (i.e., ones that result in higher dropout rates in treatment groups than in placebo groups), it is possible that last observation carried forward results in bias against memantine while favouring cholinesterase inhibitors.15

What is the source of this problem?

Discussions with researchers conducting trials of drugs for the treatment of dementia have repeatedly highlighted 2 reasons why last observation carried forward continues to be the main form of intention-to-treat analysis in dementia research. The first is lack of standards for the analysis of chronic progressive diseases in methodological guidelines such as CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials). The second is the US Food and Drug Administration's acceptance of the last-observation-carried-forward method for analysis.

A call to action

It is impossible to quantify the effect of last observation carried forward on the entire field of dementia research. To do so would require access to the raw data of all studies of dementia drugs done to date, most of which are not in the public domain. It would be naive to expect each and every pharmaceutical company that owns these proprietary data to openly share them with researchers whose reanalysis might demonstrate less effectiveness. Verification of results of individual studies is a start, but it will not resolve concerns for the entire body of research.

Given the improbability of being able to reanalyze results from all previous trials, it is more useful to focus on improving the accuracy and validity of future research. The current state of affairs represents an opportunity for the leader in Canadian research into dementia, the Consortium of Canadian Centres for Clinical Cognitive Research (C5R [www.C5R.ca]), to once again lead dementia research by promoting forums to discuss and recommend better analytical techniques.

This may be the proverbial tip of the iceberg. Scientists in other areas of research into treatments for other chronic progressive disorders (e.g., osteoporosis, Parkinson disease, stroke, multiple sclerosis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, congestive heart failure, diabetes mellitus, chronic renal insufficiency, AIDS) should review the use of last observation carried forward in these highly prevalent conditions.

Given the potentially enormous scope of this problem, the CONSORT group (www.consort-statement.org) should consider incorporating additional guidelines regarding appropriate analytical techniques for studies of medications used to treat chronic progressive disorders. Journal editors, funding agencies, ethics review boards and drug formulary committees would then be able to request that such CONSORT recommendations be followed in future studies of drugs for the treatment of dementia and other chronic progressive disorders.

The last-observation-carried-forward method provides no benefits, yet it creates unnecessary risk of generating biased or even false conclusions. The time has come for all levels of the research community to encourage licensing agencies (e.g., Health Canada, the US Food and Drug Administration and the European Agency for the Evaluation of Medicinal Products) to review the appropriateness of analyses using this method for research into drug therapies for dementia and other chronic progressive conditions and to adjust their drug-licensing standards accordingly. The patients and families that we care for and those that have made these trials possible should expect no less of us.

Key points.

The use of last observation carried forward in analyses can introduce bias that may exaggerate the effectiveness of drugs.

Last observation carried forward likely favours more toxic drugs such as cholinesterase inhibitors over less toxic drugs such as memantine.

Dementia trials may have biased or even false-positive results if the study drug is not well tolerated in the treatment group.

The CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) group should consider adding guidelines to its statement regarding the use of last observation carried forward in research on chronic progressive diseases such as dementia.

Drug-licensing agencies should decide whether to continue to accept the use of observation carried forward in research on chronic progressive diseases such as dementia.

Footnotes

Contributors: All of the authors were involved in the preparation of this manuscript and approved the final version submitted for publication.

Competing interests: None declared.

Correspondence to: Dr. Frank J. Molnar, Director of Research, University of Ottawa Division of Geriatric Medicine, The Ottawa Hospital, Civic Campus, 1053 Carling Ave., Ottawa ON K1Y 4E9; fax 613 761-5334; fmolnar@ottawahospital.on.ca

REFERENCES

- 1.Unnebrink K, Windeler J. Intention-to-treat: methods for dealing with missing values in clinical trials of progressively deteriorating diseases. Stat Med 2001;20:3931-46. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Gadbury GL, Coffey CS, Allison DB. Modern statistical methods for handling missing repeated measurements in obesity trial data: beyond LOCF. Obes Rev 2003;4:175-84. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Mallinckrodt CH, Clark WS, Carroll RJ, et al. Assessing response profiles from incomplete longitudinal clinical trial data under regulatory considerations. J Biopharm Stat 2003;13:179-90. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Mallinckrodt CH, Clark WS, David SR. Accounting for dropout bias using mixed-effects models. J Biopharm Stat 2001;11:9-21. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Aisen PS, Davis KL, Berg JD, et al. A randomized controlled trial of prednisone in Alzheimer's disease. Neurology 2000;54:588-92. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Hills R, Gray R, Stowe R. Drop-out bias undermines findings of improved functionality with cholinesterase inhibitors. Neurobiol Aging 2002;23(Suppl 1):S89.

- 7.Lanctôt KL, Herrmann N, Yau KK et al. Efficacy and safety of cholinesterase inhibitors in Alzheimer's disease: a meta-analysis. CMAJ 2003;169:557–64. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Aisen PS, Schafer KA, Grundman M, et al. Effects of refocoxib or naproxen vs. placebo on Alzheimer disease progression: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2003;289:2819-26. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Kaduszkiewicz H, Zimmermann T, Beck-Bornholdt H-P, et al. Cholinesterase inhibitors for patients with Alzheimer's disease: systematic review of randomised clinical trials. BMJ 2005;331:321-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Bullock R, Touchon J, Bergman H, et al. Rivastigmine and donepezil treatment in moderate to moderately-severe Alzheimer's disease over a 2-year period. Curr Med Res Opin 2005;21:1317-27. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Hogan DB. Donepezil for severe Alzheimer's disease. Lancet 2006;367:1031-2. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Committee for Proprietary Medicinal Products. Points to consider on missing data. London (UK): European Agency for the Evaluation of Medicinal Products; 2001. Available: www.emea.europa.eu/pdfs/human/ewp/177699EN.pdf (accessed 2008 July 24).

- 13.Streiner DL. The case of the missing data: methods of dealing with dropouts and other research vagaries. Can J Psychiatry 2002;47:68-75. [PubMed]

- 14.Petersen RC, Thomas RG, Grundman M, et al. Vitamin E and donepezil for the treatment of mild cognitive impairment. N Engl J Med 2005;352:2379-88. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Tariot PN, Farlow MR, Grossberg GT, et al. Memantine treatment in patients with moderate to severe Alzheimer disease already receiving donepezil: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2004;291:317-24. [DOI] [PubMed]