Abstract

Background

We sought to determine the lifetime prevalence of traumatic brain injury and its association with current health conditions in a representative sample of homeless people in Toronto, Ontario.

Methods

We surveyed 601 men and 303 women at homeless shelters and meal programs in 2004–2005 (response rate 76%). We defined traumatic brain injury as any self-reported head injury that left the person dazed, confused, disoriented or unconscious. Injuries resulting in unconsciousness lasting 30 minutes or longer were defined as moderate or severe. We assessed mental health, alcohol and drug problems in the past 30 days using the Addiction Severity Index. Physical and mental health status was assessed using the SF-12 health survey. We examined associations between traumatic brain injury and health conditions.

Results

The lifetime prevalence among homeless participants was 53% for any traumatic brain injury and 12% for moderate or severe traumatic brain injury. For 70% of respondents, their first traumatic brain injury occurred before the onset of homelessness. After adjustment for demographic characteristics and lifetime duration of homelessness, a history of moderate or severe traumatic brain injury was associated with significantly increased likelihood of seizures (odds ratio [OR] 3.2, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.8 to 5.6), mental health problems (OR 2.5, 95% CI 1.5 to 4.1), drug problems (OR 1.6, 95% CI 1.1 to 2.5), poorer physical health status (–8.3 points, 95% CI –11.1 to –5.5) and poorer mental health status (–6.0 points, 95% CI –8.3 to –3.7).

Interpretation

Prior traumatic brain injury is very common among homeless people and is associated with poorer health.

Traumatic brain injury is caused by “a blow or jolt to the head or a penetrating head injury that disrupts the normal function of the brain” and most commonly results from falls, motor vehicle traffic crashes and assaults.1 Traumatic brain injury is a leading cause of permanent disability in North America.1 Traumatic brain injury may be common in the homeless population.2 Exposure to physical abuse during childhood, which could result in traumatic brain injury, is a known risk factor for homelessness as an adult.3 Substance abuse increases the risk of homelessness4 and the risk of traumatic brain injury.5 Homeless people experience high rates of injury of all types and are frequently victims of assault.6,7 Finally, traumatic brain injury could be a factor contributing to the 3%–8% prevalence of cognitive dysfunction among homeless adults.8,9

Providing health care for homeless patients can be challenging for various reasons, including difficult behavioural patterns. These behaviours may be related in part to unrecognized sequelae of traumatic brain injury and may include cognitive impairment, attention deficits, disinhibition, impulsivity and emotional lability.1 Appropriate support services may be able to minimize the adverse impact of these behaviours.

Two previous studies have reported the prevalence of traumatic brain injury among homeless people in London, England, and Milwaukee, Wisconsin. These studies were limited by small sample sizes, recruitment at a single shelter and a lack of data from women.10,11 We conducted this study to determine the lifetime prevalence of traumatic brain injury in a representative sample of homeless men and women across an entire city, and to identify the temporal relation between traumatic brain injury and the onset of homelessness. We also sought to characterize the association between a history of traumatic brain injury and current health problems in this population. Our primary hypothesis was that a history of traumatic brain injury would be associated with poor current health.

Methods

Study design and population

We used a cross-sectional survey design. We recruited a representative sample of homeless people in Toronto, Ontario, where about 5000 people are homeless each night and about 29 000 people use shelters each year.12,13 We defined homelessness as living within the last 7 days at a shelter, public place, vehicle, abandoned building or someone else's home, and not having a home of one's own. Based on a pilot study, we determined that about 90% of homeless people in Toronto slept at shelters, and that 10% did not use shelters but did use meal programs.14 We therefore recruited 90% of our study participants at shelters and 10% at meal programs.

We contacted every homeless shelter in Toronto and obtained permission to enrol participants at 50 (89%) of 56 shelters (20 shelters for men, 12 for women, 6 for men and women, and 12 for youths aged 16–25 years). The number of beds at each shelter ranged between 20 and 406. Recruitment at meal programs took place at 18 sites selected at random from 62 meal programs in Toronto that served homeless people. Because the goal of recruiting at meal programs was to enrol homeless people who did not use shelters, we excluded people at meal programs who had used a shelter within the last 7 days.

We recruited participants over 12 consecutive months in 2004–2005. We stratified enrollment to achieve a 2:1 ratio of men to women. The number of participants recruited at each site was proportionate to the number of homeless people served monthly. We selected participants at random from bed lists or meal lines using a random number generator and assessed their eligibility. We excluded people who did not meet our definition of homelessness, who were unable to communicate in English and who were unable to give informed consent. We also excluded homeless shelter users who were encountered at meal programs and those who did not have a valid Ontario health insurance number, which was required to track health care use after the recruitment interview.

Previous studies have shown that homeless parents with dependent children differ substantially from homeless people without children. Homeless parents have lower rates of mental illness and substance abuse and are more likely than those without children to have become homeless for purely economic reasons.15,16 Because of these differences, this report does not include homeless parents with dependent children who were screened or enrolled in the study.

Each participant provided written informed consent and received $15 for completing the survey. This study was approved by the research ethics board at St. Michael's Hospital.

Survey instrument

Research team members administered the survey to each participant by a face-to-face interview conducted immediately after recruitment at shelters and meal programs. We obtained information on demographic characteristics and health conditions. We collected data on ethnic background because previous studies have reported racial disparities in rates of traumatic brain injury.1 Participants self-identified their ethnic background from categories adapted from the Statistics Canada Ethnic Diversity Survey.17 The most commonly selected categories were white, black and First Nations. All other categories were classified as “other.”

Mental health problems, alcohol problems and drug problems in the last 30 days were assessed using the Addiction Severity Index.18,19 The Addiction Severity Index has been validated with homeless people and has been used in numerous studies, including a nationwide survey of homeless people in the United States.20–23 Problems were dichotomized as present or absent by use of cut-off scores established for homeless populations.24 We classified participants as having mental health problems if their mental health score on the Addiction Severity Index was ≥ 0.25. They were classified as having alcohol problems if their alcohol score was ≥ 0.17 and were classified as having drug problems if their drug score was ≥ 0.10.24 We used the SF-12 health survey, a health status instrument that has been validated in homeless populations,25 to generate scores for the physical and mental component subscales.26 These scores range continuously from 0 to 100 (best), standardized to a mean of 50 and standard deviation of 10 in the general population in the United States.26

We determined a history of traumatic brain injury using questions from a study of prison inmates.27 Lifetime prevalence of traumatic brain injury was determined using the question “Have you ever had an injury to the head which knocked you out or at least left you dazed, confused or disoriented?” Participants were asked how many such injuries they had over their lifetime. For the first injury and up to 2 subsequent injuries, we obtained the date or age at injury, whether the injury resulted in unconsciousness, and the duration of unconsciousness. We used the age at which the participant first experienced homelessness to determine the temporal relation between the first traumatic brain injury and the onset of homelessness. A mild traumatic brain injury was defined as a head injury that left the person dazed, confused, or disoriented, but resulted in no unconsciousness or unconsciousness for less than 30 minutes. A moderate or severe traumatic brain injury was defined as a head injury that resulted in unconsciousness for more than 30 minutes. These definitions are consistent with standardized consensus criteria.28

Statistical analyses

We compared the characteristics of people with and without a history of traumatic brain injury using χ2 and t tests. We developed regression models to determine if a history of traumatic brain injury was associated with health conditions and health status indicators, after adjustment for sex, age, ethnic background, place of birth, education and lifetime years of homelessness. We used generalized estimating equations to account for possible clustering of the sample within shelters or meal programs. History of traumatic brain injury was entered into models as a categorical variable representing the severity of the worst traumatic brain injury ever experienced (none, mild or unknown, or moderate or severe). In our secondary analyses, both severity of the worst traumatic brain injury and the lifetime number of traumatic brain injuries were entered into models. We assessed independent variables for multicolinearity before the analyses, and no problems were detected. Analyses were conducted with unweighted data.

Results

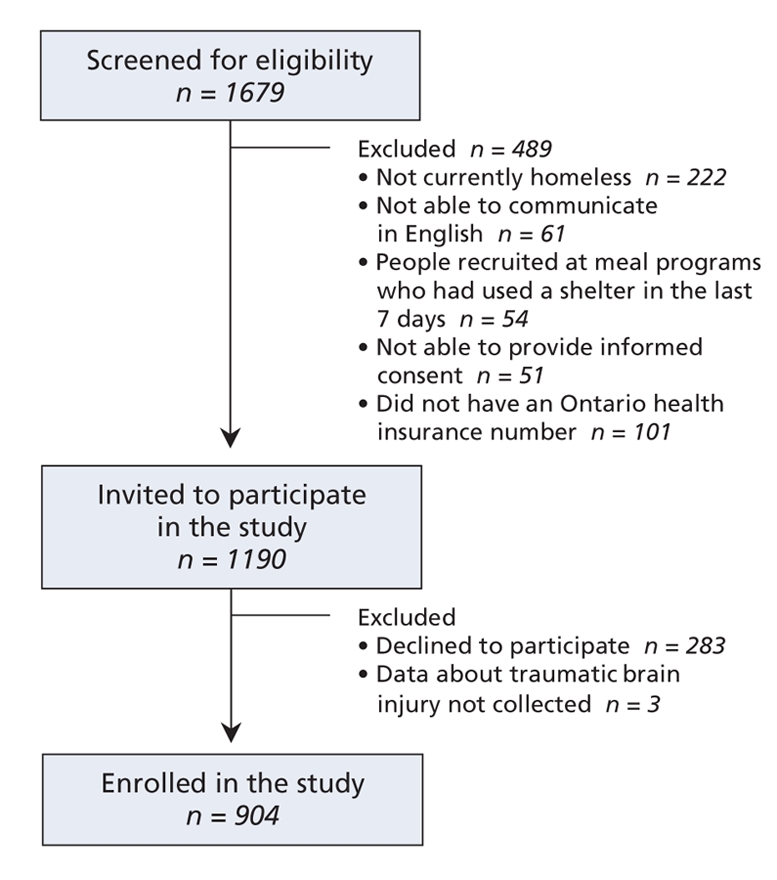

Of 1679 people screened at homeless shelters and meal programs, we included 904 people in our study (Figure 1). In total, 489 (29%) were ineligible for inclusion: 222 (13%) did not meet our definition of homelessness, 61 (4%) were unable to communicate in English, 54 (3%) were homeless shelter users encountered at meal programs, and 51 (3%) were unable to give informed consent. Because this study was part of a larger study of the utilization of health care by homeless people, we excluded 101 people (6%) because they did not have an Ontario health insurance number. Most of these 101 people were refugees, refugee claimants or had recently migrated to Ontario. Of 1190 eligible people, 283 declined to participate. We enrolled 907 (76% of eligible people) in the study. We obtained information about traumatic brain injury for 904 participants. Characteristics of study participants are shown in Table 1.

Figure 1: Flow diagram of participant recruitment.

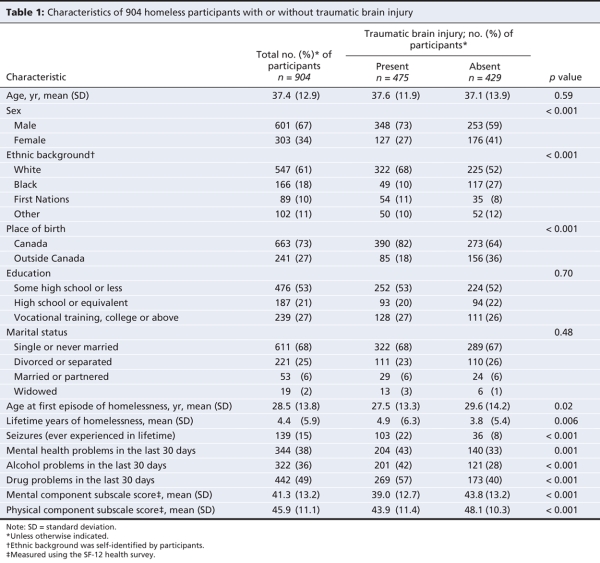

Table 1

The lifetime prevalence of traumatic brain injury was 53%. The prevalence was significantly higher among men (58%) than among women (42%, p < 0.001). Those with a history of traumatic brain injury were more likely to be male, white and born in Canada; to have become homeless for the first time at a younger age; and to have experienced more years of homelessness over their lifetime. Compared to those without a history of traumatic brain injury, participants with a history of traumatic brain injury had a significantly higher lifetime prevalence of seizures (8% v. 22%, p < 0.001); higher prevalence of mental health problems (33% v. 43%, p = 0.001), alcohol problems (28% v. 42%, p < 0.001) and drug problems (40% v. 57%, p < 0.001). They also had poorer mental health (mean score 43.8 v. 39.0, p < 0.001) and physical health (mean score 48.1 v. 43.9, p < 0.001) as measured by the SF-12 health survey (Table 1).

The mean age at first traumatic brain injury was 17.8 years. Although 40% of participants with traumatic brain injuries reported only 1 such injury, 21% reported 2 injuries, 12% reported 3 injuries, 7% reported 4 injuries, and 20% reported 5 or more injuries. The severity of the worst traumatic brain injury was mild for 66% of participants, moderate or severe for 23% and unknown for 11%. In all analyses involving traumatic brain injury severity, we grouped injuries of unknown severity with mild injuries. Analyses in which injuries of unknown severity were considered to be a separate category gave essentially identical results.

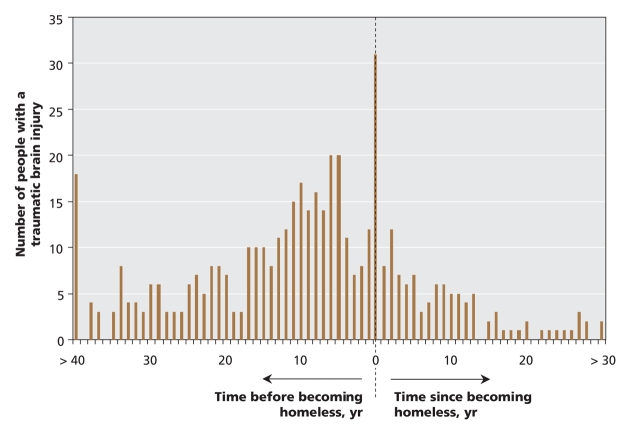

The temporal relation between the first traumatic brain injury and the first episode of homelessness is shown in Figure 2. For 70% of participants, the first traumatic brain injury occurred before the onset of homelessness. The injury occurred in the same year as the onset of homelessness for 7% of participants, and after the onset of homelessness for 22%. We could not determine the relation between the first traumatic brain injury and the first episode of homelessness for 2% of participants.

Figure 2: Homeless participants (n = 461) who experienced a traumatic brain injury before or after becoming homeless.

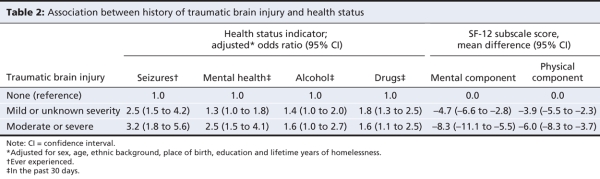

When we considered the influence of sex, age, ethnic background, place of birth, education and lifetime years of homelessness, a history of traumatic brain injury was significantly associated with seizures, mental health and drug problems, and poorer physical and mental health status (Table 2). In additional models that included both the severity of the worst traumatic brain injury and the total lifetime number of traumatic brain injuries as covariables, a higher number of traumatic brain injuries was associated with significantly increased odds of seizures and mental health, alcohol and drug problems.

Table 2

Interpretation

We found a high prevalence of traumatic brain injury in a representative sample of homeless people. A history of traumatic brain injury was more common among homeless men (58%) than among homeless women (42%). These rates are 5 or more times greater than the 8.5% lifetime prevalence rate of traumatic brain injury in the general population in the United States29 and are within the range reported in studies of traumatic brain injury among prison inmates.27,30,31

Only 2 previous studies have reported the prevalence of traumatic brain injury among homeless people. In a study of 80 consecutive entrants to a men's shelter in London, England, 46% of entrants had a lifetime history of head injury severe enough to cause unconsciousness.10 A study of 90 homeless men at a shelter in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, found that 80% of participants had possible cognitive impairment and 48% had a history of traumatic brain injury involving loss of consciousness.11 In both studies, the sample size was small, and participants were recruited at a single shelter rather than at a broad range of shelters across an entire city. In addition, homeless women and homeless people who did not use shelters were excluded.

Data from the United States have demonstrated higher rates of traumatic brain injury among African-Americans.1 In contrast, our study found a significantly lower prevalence of traumatic brain injury among homeless people who were black (30%) compared with those who were white (59%). This difference is possibly explained by the fact that traumatic brain injury was much less common among immigrants than among people born in Canada. In our study, 69% of participants who were black were immigrants to Canada.

Among homeless people, the first experience of traumatic brain injury often occurred at a young age and usually occurred before the person's first episode of homelessness. This finding suggests that, in some cases, traumatic brain injury may be a causal factor that contributes to the onset of homelessness, possibly though cognitive or behavioural sequelae of traumatic brain injury. Future research could explore this hypothesis.

History of traumatic brain injury was strongly associated with many adverse health outcomes among homeless people, including seizures, mental health problems, drug problems, and poorer physical and mental health status. A history of moderate or severe traumatic brain injury had particularly strong associations with both the presence of mental health problems within the past 30 days (OR 2.5, 95% CI 1.5–4.1) and poorer mental health status (–8.3 points on the SF-12 mental component subscale [10 points equals 1 standard deviation in the general population]). Our cross-sectional study was unable to ascertain the causal pathways responsible for these associations. Although the cognitive sequelae of traumatic brain injury may increase the risk of subsequent mental health and drug problems, it is equally plausible that pre-existing mental health, alcohol and drug problems increase the risk of experiencing traumatic brain injury.32 Likewise, homelessness could be both a contributing cause and a consequence of traumatic brain injury. Clarification of these issues would require data from a prospective longitudinal study of people with traumatic brain injury.

Strengths and limitations

Our study has a number of important strengths. We enrolled a large representative sample of both homeless men and women in a major North American city, including both those who used and those who did not use shelters. We used rigorous methods to select participants randomly at each site. We achieved a high response rate, and successfully recruited 76% of eligible people. History of traumatic brain injury was assessed using a series of questions from a previously validated survey of prison inmates.27

Certain limitations of this study should be noted. We did not enroll a control group of nonhomeless people. Our findings may not reflect rates of traumatic brain injury among homeless parents with dependent children or homeless persons who do not use shelters or meal programs. The requirement that study participants have an Ontario health insurance number resulted primarily in the exclusion of refugees and refugee claimants, whose history of traumatic brain injury may be different from that of other homeless people. We did not collect information about the mechanism or circumstances of traumatic brain injury. Prevalence and severity of traumatic brain injury as well as age at the time of traumatic brain injury were self-reported by participants and are subject to recall errors. Confirmation of these self-reports through the review of health records was beyond the scope of our study. Recently, the Traumatic Brain Injury Questionnaire has been described as a promising interview-based instrument to assess the history of traumatic brain injury in incarcerated adults.33 Future studies including homeless people should consider using this instrument. Finally, participants did not undergo formal testing for neuropsychological dysfunction that may have resulted from brain injuries.

Conclusion

Our study's findings underscore the need for clinicians to routinely ask patients who are homeless about a history of traumatic brain injury. Given the apparent dose–response relation between injury severity and current health, clinicians should assess injury severity based on information such as self-reported duration of unconsciousness, admission to hospital after the injury, collateral history and medical records. For people with a history of traumatic brain injury, brief neuropsychological screening can provide valuable information on cognitive function. People with moderate or severe cognitive impairment may be eligible for disability benefits. Referral to rehabilitaton and other appropriate community services should be considered, as recent studies have shown that rehabilitation interventions improve community integration and other outcomes among people with traumatic brain injury.34 Moreover, appropriate living environments are fundamental to community integration and are particularly important for people with more severe injuries.35 Treatment of concurrent alcohol or substance abuse should also be considered.

Future research should expand these findings by using medical records to confirm self-reported traumatic brain injury among homeless people and by correlating a history of traumatic brain injury with objectively assessed cognitive function. Cohort studies would be helpful to clarify the causal pathways that account for the high prevalence of traumatic brain injury among homeless people. Finally, research should examine the possible benefits of appropriate supportive living environments for homeless people with moderate cognitive dysfunction due to traumatic brain injury.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Stephen Hwang is the recipient of a New Investigator Award from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Donald Redelmeier is supported by the Canada Research Chair in Medical Decision Sciences.

Footnotes

Une version française de ce résumé est disponible à l'adresse www.cmaj.ca/cgi/content/full/179/8/779/DC1

Funding: This project was supported by operating grants from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (1 R01 HS014129–01) and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (MOP-62736). It was also supported by an Interdisciplinary Capacity Enhancement grant on Homelessness, Housing and Health from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (HOA-80066). The project was also supported by a grant from the Ontario Neurotrauma Foundation and the Toronto Rehabilitation Institute Foundation. The Centre for Research on Inner City Health, the Toronto Rehabilitation Institute and the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences gratefully acknowledge the support of the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care.

This article has been peer reviewed.

Contributors: All of the authors contributed to the study concept and design. Stephen Hwang and Shirley Chiu acquired the data. Stephen Hwang, Shirley Chiu and Alex Kiss performed the statistical analyses. Angela Colantonio, Donald Redelmeier and Wendy Levinson contributed to the analysies. They, along with Stephen Hwang, Shirley Chiu and Alex Kiss, interpreted the data. Stephen Hwang and Shirley Chiu drafted the manuscript, and all of the authors critically revised it for important intellectual content and approved the final version submitted for publication.

We thank Marko Katic, Department of Research Design and Biostatistics, Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre, for expert programming and analyses. We are grateful for collaboration with the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences. The views expressed in this publication are the views of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care or any of the other above-named organizations.

Competing interests: None declared.

Correspondence to: Dr. Stephen W. Hwang, Centre for Research on Inner City Health, St. Michael's Hospital, 30 Bond St., Toronto ON M5B 1W8; fax 416 864-5485; hwangs@smh.toronto.on.ca

REFERENCES

- 1.National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. What is traumatic brain injury? Atlanta (GA): The Centre for Disease Control; 2008. Available: www.cdc.gov/ncipc/tbi/TBI.htm (accessed 2008 Aug 27).

- 2.Waldmann CA. Traumatic brain injury (TBI). In: O'Connell JJ, editor. The health of homeless persons: a manual of communicable disease and common problems in shelters and on the streets. Boston (MA): Boston Health Care for the Homeless Program and the National Health Care for the Homeless Council; 2004. p. 237-41.

- 3.Herman DB, Susser ES, Struening EL, et al. Adverse childhood experiences: Are they risk factors for adult homelessness? Am J Public Health 1997;87:249-55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Susser E, Moore R, Link B. Risk factors for homelessness. Epidemiol Rev 1993;15:546-56. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Corrigan JD. Substance abuse as a mediating factor in outcome from traumatic brain injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1995;76:302-9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Zakrison TL, Hamel PA, Hwang SW. Homeless people's trust and interactions with police and paramedics. J Urban Health 2004;81:596-605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Kushel MB, Evans JL, Perry S, et al. No door to lock: victimization among homeless and marginally housed persons. Arch Intern Med 2003;163:2492-9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Spence S, Stevens R, Parks R. Cognitive dysfunction in homeless adults: a systematic review. J R Soc Med 2004;97:375-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Kass F, Silver JM. Neuropsychiatry and the homeless. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 1990;2:15-9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Bremner AJ, Duke PJ, Nelson HE, et al. Cognitive function and duration of rooflessness in entrants to a hostel for homeless men. Br J Psychol 1996;169:434-9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Solliday-McRoy C, Campbell TC, Melchert TP, et al. Neuropsychological functioning of homeless men. J Nerv Ment Dis 2004;192:471-8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.City of Toronto. The Toronto report card on housing and homelessness 2003. Toronto (ON): The City; 2003. Available: www.toronto.ca/homelessness/pdf/reportcard2003.pdf (accessed 2008 Aug 27).

- 13.Brown P. 2006 Street needs assessment: results and findings, Toronto (ON): Shelter, Support and Housing Administration, The City of Toronto; 2006. Available: www.toronto.ca/housing/pdf/streetneedsassessment.pdf (accessed 2008 Aug 27).

- 14.Hwang SW, Chiu S, Kiss A, et al. Use of meal programs and shelters by homeless people in Toronto. J Urban Health 2005;82(Suppl 2):ii46.

- 15.Robertson MJ, Winkleby MA. Mental health problems of homeless women and differences across subgroups. Annu Rev Public Health 1996;17:311-36. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Shinn M, Weitzman BC, Stojanovic D, et al. Predictors of homelessness among families in New York City: from shelter request to housing stability. Am J Public Health 1998;88:1651-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Housing, Family and Social Statistics Division. Ethnic diversity survey questionnaire. Ottawa (ON): Statistics Canada; 2002. Available: www.statcan.ca/english/sdds/instrument/4508_Q1_V1_E.pdf (accessed 2008 Aug 27).

- 18.McGahan PL, Griffith JA, Parente R, et al. Addiction Severity Index: composite scores manual. Philadelphia (PA): The University of Pennsylvania, Veterans Administration Centre for Studies of Addiction; 1986. Available: www.tresearch.org/resources/compscores/CompositeManual.pdf (accessed 2008 Aug 27).

- 19.McLellan AT, Kushner H, Metzger D, et al. The fifth edition of the Addiction Severity Index. J Subst Abuse Treat 1992;9:199-213. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Zanis DA, McLellan AT, Canaan RA, et al. Reliability and validity of the Addiction Severity Index with a homeless sample. J Subst Abuse Treat 1994;11:541-8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Joyner LM, Wright JD, Devine JA. Reliability and validity of the Addiction Severity Index among homeless substance misusers. Subst Use Misuse 1996;31:729-51. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Drake RE, McHugo GJ, Biesanz JC. The test-retest reliability of standardized instruments among homeless persons with substance use disorders. J Stud Alcohol 1995;56:161-7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Burt M, Aron LY, Lee E. Helping America's homeless. Washington (DC): The Urban Institute Press; 2001.

- 24.Burt MR, Aron LY, Douglas T. Homelessness: programs and the people they serve. Findings of the National Survey of Homeless Assistance Providers and Clients. Washington (DC): United States Interagency Council on the Homelessness; 1999.

- 25.Larson CO. Use of the SF-12 Instrument for measuring the health of homeless persons. Health Serv Res 2002;37:733-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Ware JE, Kosinski M, Keller SD. SF-12: How to score the SF-12 physical and mental health summary scales. 2nd ed. Boston (MA): The Health Institute, New England Medical Center; 1995.

- 27.Slaughter B, Fann JR, Ehde D. Traumatic brain injury in a county jail population: prevalence, neuropsychological functioning and psychiatric disorders. Brain Inj 2003;17:731-41. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Kay T, Harrrington DE, Adams R et al. Definition of mild traumatic brain injury. J Head Trauma Rehabil 1993;8:86-7.

- 29.Silver JM, Kramer R, Greenwald S, et al. The association between head injuries and psychiatric disorders: findings from the New Haven NIMH Epidemiologic Catchment Area Study. Brain Inj 2001;15:935-45. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Schofield PW, Butler TB, Hollis SJ, et al. Traumatic brain injury among Australian prisoners: rates, recurrence and sequelae. Brain Inj 2006;20:499-506. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Morrell RF, Merbitz CT, Jain S, et al. Traumatic brain injury in prisoners. J Offend Rehabil 1998;27:1-8.

- 32.Parry-Jones BL, Vaugh FL, Cox VM. Traumatic brain injury and substance misuse. A systematic review of prevalence and outcomes research (1994-2004). Neuropsychol Rehabil 2006;16:537-60. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Diamond PM, Harzke AJ, Magaletta PR, et al. Screening for traumatic brain injury in an offender sample: a first look at the reliability and validity of the Traumatic Brain Injury Questionnaire. J Head Trauma Rehabil 2007;22:330-8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Gordon WA, Zafonte R, Cicerone K, et al. Traumatic brain injury rehabilitation: state of the science. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2006;85:343-82. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Kelly G, Winkler D. Long-term accommodation and support for people with higher levels of challenging behaviour. Brain Impair 2007;8:262-75.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.