Abstract

Selective inactivation of critical cysteine residues in human immunodeficiency virus type one (HIV-1) was observed after treatment with 4-vinylpyridine (4-VP), with and without the membrane-permeable metal chelator N,N,N′,N′-tetrakis(2-pyridylmethyl)-ethylenediamine (TPEN). Chromatographic analysis showed that cysteines contained within nucleocapsid zinc fingers, in the context of whole virus or purified protein, were essentially unreactive, but became reactive when a chelator was included. Virus treated with 4-VP showed only a modest decrease in infectivity; after TPEN addition, nearly complete inactivation of HIV-1 occurred. Similarly, quantitation of viral DNA products from 4-VP-treated virus infections showed no significant effects on reverse transcription, but did show a 14-fold reduction in proviruses; when TPEN was added, a 105-fold decrease in late reverse transcription products was observed and no proviruses were detected. Since 4-VP effectiveness was greatly enhanced by TPEN, this strongly suggests that modification of nucleocapsid zinc fingers is necessary and sufficient for HIV-1 inactivation by sulfhydryl reagents.

Keywords: HIV-1, Nucleocapsid, Zinc finger, Reverse transcription, Provirus, Sulfhydryl reagents

Introduction

Nucleocapsid (NC) proteins perform several essential functions in the human immunodeficiency virus type one (HIV-1) replication cycle. As part of the Gag polyprotein, NC recognizes and packages the viral genome during assembly of new virions (Vogt, 1997). Once it is cleaved from Gag by the viral protease, the small and highly basic NC protein acts as a nucleic acid chaperone during reverse transcription (reviewed in Levin et al., 2005; Rein et al., 1998) and integration (Buckman et al., 2003; Carteau et al., 1997, 1999; Poljak et al., 2003; Thomas et al., 2006; Thomas and Gorelick, in press), and also protects newly synthesized viral DNA (vDNA) from cellular nucleases (Buckman et al., 2003; Tanchou et al., 1998; Thomas et al., 2006).

NC is mostly unstructured when not bound to nucleic acids (Lee et al., 1998), but two features are notable. Clusters of basic residues and zinc finger motifs facilitate binding to nucleic acids both nonspecifically and to specific, high affinity sequences. The basic residues bind to the phosphodiester backbone of nucleic acids, and the zinc fingers allow NC to form highly specific interactions with nucleobases (De Guzman et al., 1998; Fisher et al., 1998, 2006). As the name implies, Zn2+ is at the core of retroviral NC zinc finger domains and forms a tetrahedral coordination complex (Bess et al., 1992; Chance et al., 1992; Summers et al., 1992) with cysteine and histidine residues in the characteristic, highly conserved pattern -C-X2-C-X4-H-X4-C- (CCHC; Berg, 1986; Covey, 1986; Henderson et al., 1981). Except for gammaretroviruses, which have a single zinc finger, all orthoretroviruses have two copies of this motif.

Retroviral NC zinc fingers are small, only fourteen residues in length, but crucial for viral replication. Zn2+ coordination is essential for maintaining the correct structure of these domains, and point mutations that eliminate Zn2+ binding result in noninfectious virus (Gorelick et al., 1988, 1990). Even mutations that preserve Zn2+ binding, such as cysteine to histidine, histidine to cysteine, or exchanging the positions of the zinc fingers can completely block viral replication (Buckman et al., 2003; Gorelick et al., 1993, 1999; Guo et al., 2002; Tanchou et al., 1998). Additionally, the two zinc fingers in HIV-1NC are not equivalent in either their role in viral replication or their chemical reactivity. The N-terminal zinc finger plays a more prominent role in replication (Gorelick et al., 1993, 1999). Experimental modification of cysteine residues in purified NC has provided evidence that the two zinc fingers also differ in chemical reactivity, the C-terminal zinc finger, and especially Cys49, being more available for reaction with electrophiles (Chertova et al., 1998; Hathout et al., 1996; Huang et al., 1998a; Maynard et al., 1998; Tummino et al., 1996).

NC cysteine residues, critical for maintaining the structure of the zinc finger domains, make attractive targets for chemical inactivation of HIV-1. Electrophilic molecules with sufficient redox potential (Topol et al., 2001) that are also capable of crossing the viral membrane will oxidize NC cysteines, thereby destroying the zinc finger structure and inactivating the virus (Rice et al., 1993, 1995). For example, 2,2′-dipyridyl disulfide (also known as Aldrithiol-2; AT-2) is used to chemically inactivate HIV-1 for experimental and vaccine research purposes in both animals and humans (Lifson et al., 2004; Lu et al., 2004b; Rossio et al., 1998). NC can similarly be modified by the sulfhydryl reagent N-ethylmaleimide (NEM), which alkylates the cysteine residues and consequently destroys the zinc finger structure of NC (Chertova et al., 1998; Morcock et al., 2005).

While perturbing cysteines within NC zinc fingers is sufficient for inactivating HIV-1, the necessity of modifying these residues is unclear. Reagents such as AT-2 and NEM can react with any viral protein that contains cysteine, not just NC, so the possibility exists that modification of these other proteins may contribute to the inactivation of HIV-1. A reagent that is un-reactive with the Zn2+-bound cysteines of NC would be useful for investigating both the importance of these residues and the importance of other cysteine-containing proteins to the chemical inactivation of HIV-1; we present evidence that the sulfhydryl reagent 4-vinylpyridine (4-VP) possesses this characteristic.

We show in experiments with purified proteins in vitro that 4-VP was essentially unreactive with Zn2+-bound NC but reacted readily with apo-NC. Intact HIV-1 particles were also treated with 4-VP, alone or in the presence of a membrane-permeable divalent metal ion chelator. The effects of these treatments on infectivity and early steps in viral replication were examined in reporter cell and quantitative PCR assays.

Alone, 4-VP reduced virus infectivity moderately (~10-fold), which could be correlated with a reduction in the number of vDNA integrations into the host genome. This correlation indicates that in addition to NC, free cysteine residues in other proteins may be needed for maximum integration efficiency. However, 4-VP in combination with a membrane-permeable chelator rendered integration undetectable. In addition, the synthesis of both early and late vDNA products was severely inhibited and HIV-1 titer was significantly affected. These results suggest that the cysteine residues of NC’s zinc fingers are the principal targets in sulfhydryl-mediated chemical inactivation of HIV-1.

Results

Virus infectivity

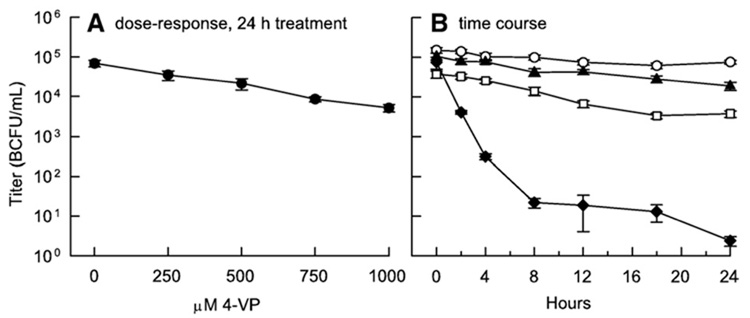

We performed experiments to determine the effect of drug treatment on virus infectivity. After treating HIV-1 with 4-VP or 4-VP+ N,N,N′,N′-tetrakis(2-pyridylmethyl)-ethylenediamine (TPEN; a membrane-permeable metal chelator), infectivity was measured using a β-galactosidase reporter cell assay. A dose–response experiment demonstrated that 4-VP treatment had a rather modest effect on infectivity. After 24 h of treatment with 1 mM 4-VP, the highest concentration used, viral titer decreased by only 1.1 orders of magnitude with respect to untreated virus (Fig. 1A); lower concentrations had progressively less of an effect.

Fig. 1.

Inactivation of HIV-1. Error bars represent the standard deviation of between two and seven samples for each point. After treatment, unreacted 4-VP and TPEN were neutralized with 4 mM GSH and 100 µM Zn2+, respectively. (A) Virus was treated with various concentrations of 4-VP for 24 h, then the infectious titers were determined from β-galactosidase expression of TZM-bl cells, as described in Materials and methods. Titers are reported as blue cell forming units per mL (BCFU/mL). (B) Effect of 4-VP on virus infectivity, with and without TPEN; virus inactivation was monitored over 24 h. HIV-1 was incubated with PBS (○), 50 µM TPEN (▲), 1 mM 4-VP (□), and 1 mM 4-VP+50 µM TPEN (◆), and viral titers were determined as above. For times 2 h and later, the differences between VP+TPEN and the other treatments are significant based on ANOVA and post hoc Tukey tests, with p<0.001. Medium only was used to determine background levels of blue cells, which were typically <1.6 blue cell forming units per mL (BCFU/mL).

Next, the importance of metal binding to the reactivity of viral proteins with sulfhydryl reagents in the context of intact virions was tested by treating HIV-1 with the metal chelator TPEN at 50 µM in combination with 1 mM 4-VP. TPEN has several properties which make it well suited for this purpose. Its affinity for Zn2+ (log K = 15.6; Anderegg et al., 1977) is greater than that of the HIV-1 NC zinc fingers (log K = 14.54 and 13.23 for the N- and C-terminal zinc fingers, respectively; Mély et al., 1996). Additionally, TPEN is membrane permeable and has low affinity for calcium and magnesium ions at physiological pH (Arslan et al., 1985). Samples of virus treated with the different combinations of drugs and relevant controls were collected over a 24 h period and assayed for infectivity as before (Fig. 1B). The infectivity of untreated virus decreased by 0.3 orders of magnitude over the 24 h period. Consistent with the dose–effect results (Fig. 1A), 1 mM 4-VP reduced infectivity by 1.3 orders of magnitude. TPEN alone reduced viral infectivity by 0.6 orders of magnitude (not significantly different from untreated virus), suggesting that viral proteins were able to reacquire Zn2+ removed by the chelator. However, when HIV-1 was exposed to both 1 mM 4-VP and 50 µM TPEN, viral infectivity was reduced by 4.5 orders of magnitude after 24 h (for time points 2 h and later, the difference was significant compared to all other treatments; p<0.001 based on ANOVA and post hoc Tukey tests; Fig. 1B). Reagent control treatments of virus [4 mM reduced glutathione (GSH; used to quench 4-VP), 100 µM Zn2+ (used to prevent TPEN cytotoxicity), 4 mM GSH+100 µM Zn2+, or 0.05% (v/v) ethanol (the solvent for TPEN)] did not cause any reduction in titer compared to untreated virus (data not shown). Individually, 4-VP and TPEN were poorly virucidal, but when the two reagents were used together, they effectively and significantly inactivated HIV-1, which supported the idea that the majority of the critical Cys residues are bound to Zn2+.

Reverse transcription

To determine how the 4-VP and 4-VP+TPEN treatments reduced infectivity, we examined the activity of reverse transcriptase (RT) from treated viruses, as well as reverse transcription in cells after infection with treated viruses. RT activity in viral lysates was measured with an exogenous template assay for RNA-dependent DNA polymerase activity (Gorelick et al., 1990, 1999). Treating HIV-1 for 18 h at 37 °C with 1 mM 4-VP and 50 µM TPEN, singly or combined, did not significantly reduce RT activity (Table 1). Virus treated with 4 mM GSH, 100 µM Zn2+, or 0.05% (v/v) ethanol also retained similar levels of exogenous template RT activity. Heat-inactivated virus had no detectable RT activity, as expected. Because drug treatment did not significantly reduce RT activity in the exogenous template assay, it is unlikely to be the principal target in virio. Therefore, we investigated the ability of treated viruses to reverse transcribe their genomes after infection of cells.

Table 1.

Viral DNA intermediates

| Treatment | RT activity a | CCR5 copy # (× 104) | Relative copy number | Relative efficiency | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R-U5 | R-5′UTR | Provirus | Reverse transcription b | Integration c | |||

| Untreated HIV-1 | 100±0.19 | 7.1±0.1 | 100±6 d | 100±4 e | 100±18 f | 100±7 g | 100±18 h |

| GSH | 104±0.17 | 6.4±0.7 | 137±7 | 115±17 | 87±15 | 84±13 | 76±17 |

| Zn2+ | 111±0.15 | 5.0±0.09 | 117±7 | 111±5 | 92±16 | 95±7 | 83±15 |

| Zn2++GSH | 115±0.21 | 8.0±1 | 100±12 | 82±3 | 78±10 | 82±10 | 95±12 |

| TPEN | 87±0.21 | 6.8±0.5 | 70±9 | 48±7 | 26±8 | 68±13 | 55±19 |

| 4-VP | 139±0.16 | 6.6±0.7 | 49±18 | 31±8 | 7±1 | 63±28 | 22±6 |

| TPEN+4-VP | 80±0.14 | 6.7±0.5 | 6.7±0.4 | 0.081±0.002 | – | 1.2±0.1 | – |

| IND116N | 46±0.21 | 9.0±2 | 39±2 | 25±3 | – | 65±8 | – |

| Ethanol | 102±0.16 | 6.5±0.7 | 90±9 | 67±8 | 43±11 | 75±11 | 64±18 |

| Heat inactivated i | 0 | 6.6±0.1 | 0.03±0.02 | 0.012±0.001 | – | – | – |

| Negative control j | 0 | 8.1±0.04 | – | – | – | – | – |

Exogenous template reverse transcriptase activity. 100%=(1.1±0.2)× 106 counts of TMP incorporated per minute. Samples were analyzed in triplicate.

Reverse transcription efficiency was defined as the ratio of R-5′UTR/R-U5 copy numbers and shown as a percentage of untreated HIV-1.

Integration efficiency was defined as the ratio of provirus/R-5′UTR copy numbers and shown as a percentage of untreated HIV-1.

100%=(8.3±0.4)× 105 copies per sample. Copy numbers were corrected for DNA recovery and RT activity.

100%=(3.7±0.1)× 105 copies per sample.

100%=(1.5±0.2)× 105 copies per sample. The limit of detection for the provirus assay is 100 copies (Thomas et al., 2006).

Actual efficiency was 0.45±0.02 (equivalent to R-5′UTR/ R-U5 copies).

Actual efficiency was 0.40±0.05 (equivalent to provirus/ R-5′UTR copies).

Virus was incubated at 68 °C for 20 min.

Mock transfections of HEK 293T cells with sheared salmon sperm DNA.

HIV-1 pseudotyped with vesicular stomatitis virus G (VSV-G) protein was treated for 18 h with 4-VP, with and without TPEN. The reagents were neutralized with GSH or Zn2+, as relevant, prior to application to cells. The treated virus preparations were used to infect human osteosarcoma (HOS) cells for 24 h. Specific vDNA products were quantitated using real-time PCR. The data were normalized for recovered total DNA using CCR5 copy numbers from the HOS cells (similar CCR5 levels among all of the samples also verified the absence of cytotoxicity associated with treatments; Table 1) and for input virus using RT activity, as described previously (Buckman et al., 2003; Thomas et al., 2006). Copy numbers relative to untreated virus are presented for minus-strand strong-stop DNA (R-U5), plus-strand transfer DNA (R-5′ UTR), and provirus (Alu-LTR); all are reported as percentages of untreated virus. In addition to the individual species detected, the efficiency of reverse transcription for a particular treatment, presented as the percent efficiency of untreated virus was calculated from the ratio of R-5′UTR to R-U5 copy numbers (indicates conversion of early to late vDNA products). Similarly, integration efficiency for a particular treatment, presented as the percent efficiency of untreated virus, was calculated from the ratio of provirus to R-5′UTR copy numbers (indicates conversion of late vDNA products to proviruses; Table 1).

Treating viruses with the combination of 4-VP+TPEN reduced vDNA synthesis significantly more than 4-VP alone. After treatment with 4-VP, HIV-1 synthesized vDNA with a modest (~40%) decrease in reverse transcription efficiency, while the efficiency of provirus formation was reduced ~80% (Table 1). Combining TPEN with 4-VP had a much greater effect on vDNA synthesis. Reverse transcription efficiency was reduced 99% and proviruses could not be detected, which is consistent with the loss of infectious titer following treatment with 4-VP+TPEN described above (Fig. 1B). Control virus treatments using Zn2+ and GSH synthesized vDNA in amounts similar to untreated virus in the HOS cell infections. HIV-1 treated with TPEN or ethanol showed only a small decrease in vDNA levels. Synthesis of vDNA by IND116N (an integration-negative mutant virus; Engelman et al., 1995) was reduced, in agreement with previous reports (Buckman et al., 2003; Thomas et al., 2006). Heat-inactivated HIV-1 showed negligible levels of vDNA signals, indicative of very low levels of contaminating plasmid present in the samples (<0.03% of the untreated samples). Despite the presence of active RT, the combination of 4-VP and TPEN severely inhibited the earliest steps of reverse transcription.

HPLC analysis

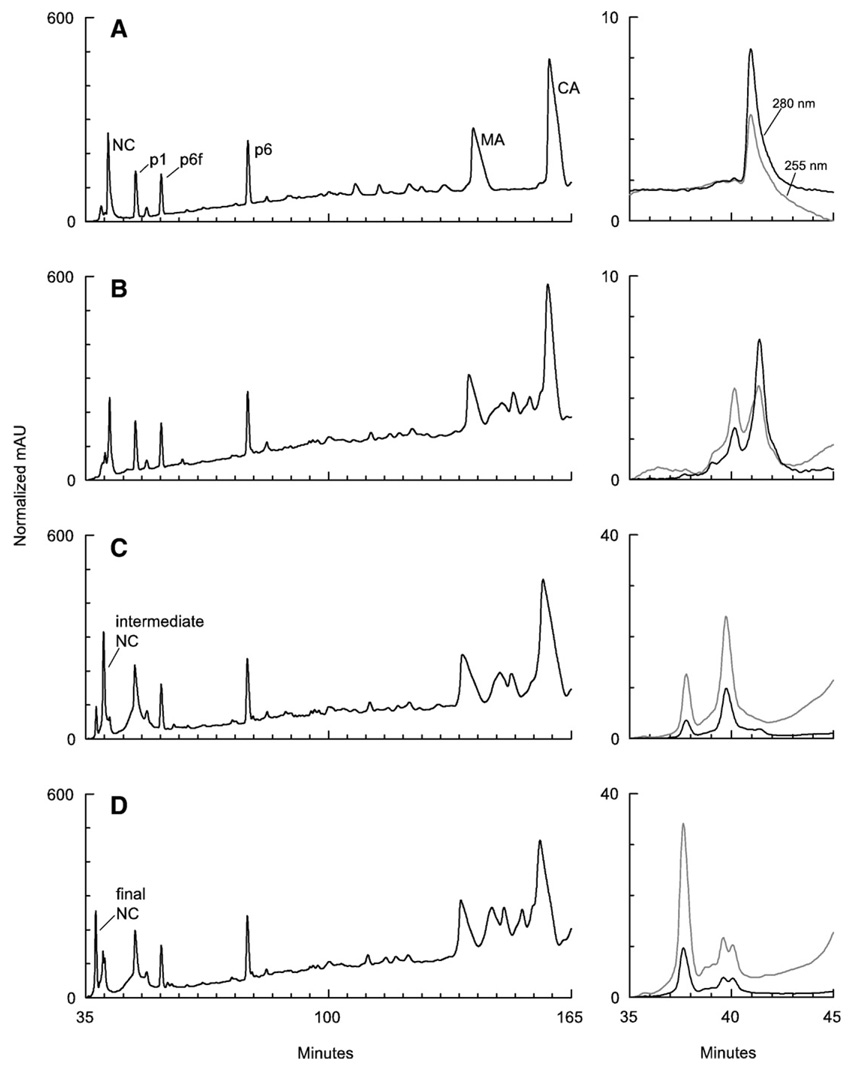

Although 4-VP inactivated HIV-1 to a limited extent, the reagent did have an effect on infectivity and integration of vDNA, indicating that proteins within the virus reacted with 4-VP; the effect was much greater when a metal chelator was included. To identify the principal viral proteins modified by 4-VP, HIV-1 from clarified pNL4-3 transfection supernatant was treated as follows. Virus was either untreated, treated for 18 h with 1 mM 4-VP only, or for 3 h or 18 h with 1 mM 4-VP+50 µM TPEN. Virus was then collected by ultracentrifugation, lysed and reduced, then analyzed with reverse phase microcapillary high-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC). Pyridylethylation could be identified by the appearance of a new peak eluting earlier than the parent protein peak and by an increase in the ratio of absorbance at 255–260 nm relative to 280 nm (because of ethylpyridine adding to tryptophan’s absorbance). Viral proteins p1 (also known as spacer peptide 2; SP2) and p6, which lack cysteine, were used as internal standards for peak alignments. Fig. 2A shows the elution pattern of Gag proteins from untreated virus, which had an NC A255/A280 ratio of 0.55; treatment with TPEN alone for 18 h was equivalent to untreated virus (data not shown).

Fig. 2.

HPLC analysis of HIV-1 treated with 4-VP, with and without TPEN. Absorbance at 206 nm is shown in panels on the left. Panels on the right show enlargements of 255 and 280 nm absorbance from the same sample, depicting the elution of NC and derivatives. Virus was (A) untreated, (B) treated with 1 mM 4-VP for 18 h, (C) 4-VP+50 µM TPEN for 3 h, or (D) 4-VP+TPEN for 18 h. HIV-1 treated for 18 h with TPEN alone was equivalent to untreated virus (data not shown). The data were normalized as described in Materials and methods.

NC did not react significantly in HIV-1 treated with 1 mM 4-VP (NC A255/A280=0.62; Fig. 2B). A shoulder did appear on the NC peak, but this may have been the result of 4-VP reacting with spontaneously oxidized NC, since A255/A280 increased to 1.82. Spontaneous oxidation of cysteine in the zinc finger domains of NC to disulfide or other species is common in purified virus (L. Henderson, unpublished observations). Such oxidation would decrease Zn2+ coordination, thus leaving the remaining free cysteines susceptible to 4-VP. Despite this, the bulk of NC was unmodified by 4-VP as judged by 255 and 280 nm absorbance and the peak’s elution position.

Likewise, neither MA nor CA in whole virus reacted appreciably with 4-VP (with or without TPEN). Separate experiments with purified proteins identified the elution positions of 4-VP-modified MA and CA, and confirmed that the 4-VPmodified forms could be separated from the unmodified proteins under our chromatographic conditions (data not shown). Both proteins were recovered in their unmodified state from treated virus in yields exceeding 85% of expected values. In addition, the absence of a peak at the elution position for modified MA indicates that this species is absent in the modified virus (Fig. 2). The elution position for modified CA is complicated by unknown, presumably cellular material, but the peak had low 255 nm absorbance indicating that it had not been pyridylethylated and therefore is likely irrelevant (data not shown). Taken together, these observations strongly support the conclusion that neither MA nor CA is modified by our treatments.

Combining TPEN with 4-VP dramatically increased the derivatization of NC. After 18 h, NC from virus treated with 4-VP alone had reacted fractionally as judged by its 255/280 nm absorbance ratio and its elution position (Fig. 2B). In contrast, after only 3 h of exposure to 1 mM 4-VP and 50 µM TPEN, unmodified NC had been replaced by two new peaks (Fig. 2C), corresponding to intermediate and final reaction products, whose increased absorbance at 255 nm (A255/A280=2.46 and 3.51, respectively) was characteristic of pyridylethylated protein. The intermediate product was more abundant at 3 h, but after 18 h of treatment the final product was predominant (Fig. 2D). In the latter case, two intermediate peaks (A255/A280=1.9 and 2.6) were observed in addition to the final product (A255/A280=3.4). Based on the results reported by Chertova et al., the intermediate product likely was NC modified on the C-terminal zinc finger, and the final product corresponded to protein modified on both zinc fingers (Chertova et al., 1998). 4-VP reacted with NC in whole virus only when Zn2+ was removed from the protein (e.g., via the addition of TPEN), exposing its cysteine residues.

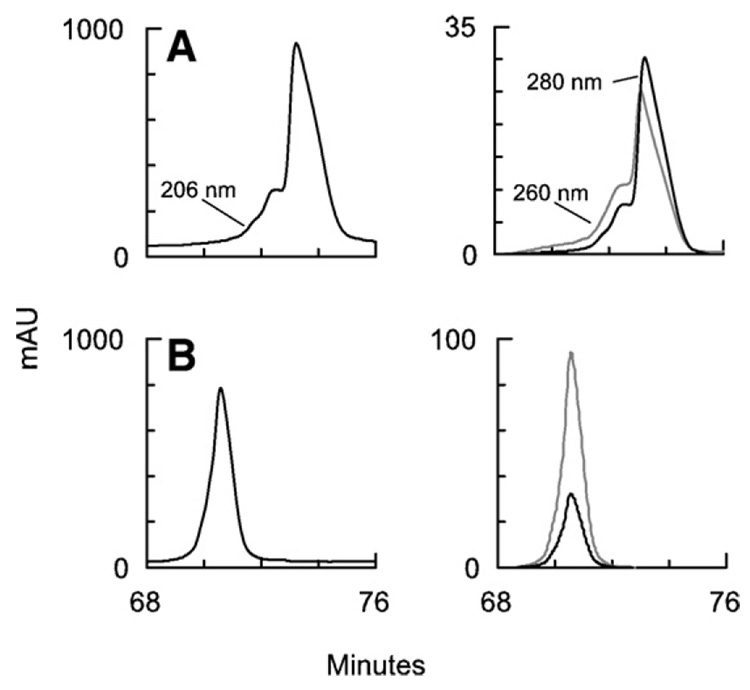

HPLC analysis of NC protein

To further elucidate the mechanism of NC modification, we examined purified recombinant HIV-1NL4-3 NC (p7 form) treated with 4-VP, with or without metal chelators. A solution of 7.7 µM NC (with 6 cysteines), 89 mM 4-VP, and 10 mM Tris buffer, pH 7.5, in a total volume of 20 µL was reacted at 25 °C for 195 min. and then injected onto an HPLC column. Despite the ~2000-fold excess of 4-VP over cysteine, no derivatized NC was detected (Fig. 3A); however, as with whole virus, a shoulder with increased A260 relative to A280 appeared, which may again stem from spontaneous oxidation of NC exposing cysteine during the reaction (see above). Next, a solution of 6.3 µM NC, 35 mM 4-VP, 5 mM EDTA (for removal of Zn2+), and 10 mM Tris buffer, pH 7.5, in a total volume 25 µL was reacted at 25 °C for 20 min. and injected onto an HPLC column. In the absence of coordinated Zn2+, NC reacted extensively and rapidly with 4-VP, eluting earlier from the HPLC column with increased absorbance at 260 nm relative to 280 nm (Fig. 3B). Unmodified NC was not observed after this treatment.

Fig. 3.

HPLC analysis of purified HIV-1 NC p7 protein after 4-VP treatment. Absorbance at 206 nm is shown on the left, 260 and 280 nm absorbance on the right. (A) HIV-1 NC p7 in 10 mM Tris buffer, pH 7.5, was treated with 4-VP only (~2000×[Cys]) for 195 min or (B) with 4-VP (~1000×[Cys])+EDTA for 20 min.

Separately, NC dissolved in HPLC lysis buffer plus 10 mM EDTA was treated with excess 4-VP to produce fully derivatized NC for comparison with treated virus. Protein purified by HPLC was collected for mass spectrometry. The expected mass for HIV-1 NC p7 containing six pyridylethyl-cysteine residues is 6981.4 Da, and the observed mass was 6987.3 Da (0.08% difference). While untreated NC had an A255/A280 ratio of 0.55 (see previous section), NC that was fully derivatized had an A255/A280 ratio of 3.58, similar to the absorbance ratios of 3.4 and 3.51 observed above for the final NC reaction products from whole virus treated with 4-VP and TPEN.

Discussion

Whole virus is efficiently inactivated by comparatively strong oxidizing reagents such as AT-2 or alkylating agents such as NEM, and it is presumed that the principal targets for modification are the Cys residues of the NC protein (Morcock et al., 2005; Rossio et al., 1998). However, there are a number of other proteins in HIV-1 virions that contain Cys, so the argument for NC being the principal target is based on indirect evidence. For instance, RT contains several cysteine residues, but exogenous template RT activity is essentially unaffected by AT-2, NEM, or, in the present case, 4-VP+TPEN (Table 1; above references) so RT does not appear to be a principal target. However, reverse transcription processes during infection show profound defects with these treatments (Morcock et al., 2005; Rossio et al., 1998; Table 1). In addition, experiments that compared the sensitivity of two divergent retroviruses, Moloney murine leukemia virus (MuLV) and human foamy virus (HFV), to the sulfhydryl reagent AT-2 showed that the infectious titer of MuLV (an orthoretrovirus containing NC zinc fingers) is reduced, but HFV (a spumare-trovirus lacking zinc fingers) is unaffected by the reagent (Rein et al., 1996). Taken together, these results suggest that the cysteines in NC, a protein that is central to reverse transcription processes through its chaperone function (Levin et al., 2005; Rein et al., 1998), are the principal targets for these sulfhydryl reagents.

The present study investigates the impact of a mildly reactive sulfhydryl reagent on HIV-1 infectivity, and thereby explores the requirement for modifying NC rather than other non-Zn2+-complexed Cys residues. Uniquely characteristic to this system, used alone, 4-VP was poorly effective at inactivating HIV-1 and alkylating NC unless a metal chelator was added. In infectivity assays, 4-VP reduced viral titer by one order of magnitude after 24 h of treatment (Fig. 1A). However, adding TPEN greatly increased the rate and extent of virus inactivation, reducing infectivity by 4.5 orders of magnitude within 8 h (Fig. 1B). In addition, HPLC analyses demonstrated that the NC protein was completely modified by 4-VP+chelator treatment (Fig. 2D and Fig. 3B). Significant differences in reverse transcription during infection were also observed between the 4-VP treatments, with and without the chelator (Table 1). Singly, 4-VP reduced vDNA synthesis only two-to three-fold while reducing integration 14-fold. In contrast, when the reagent was combined with TPEN, synthesis of minus-strand strong-stop DNA was reduced 15-fold, synthesis of plus-strand transfer DNA was reduced 1200-fold, and proviruses were undetectable (> 1500-fold reduction based on detection limits; Table 1). These results support the conclusion that NC cysteines are sufficient targets for virus inactivation by sulfhydryl reagents.

The difference between these two treatments can be explained by 4-VP’s selective reactivity with NC, based upon Zn2+ coordination in the zinc fingers. Chromatographic analysis showed that, in contrast to the sulfhydryl reagent NEM (Chertova et al., 1998; Morcock et al., 2005), 4-VP did not readily react with NC, in purified form or within virions, while the protein’s cysteine residues were coordinated by Zn2+ (Fig. 2B and Fig. 3A). NC in virions reacted rapidly and extensively only when HIV-1 was treated with 4-VP in the presence of TPEN, but none of the other major viral proteins detected in our HPLC assay showed increased reactivity after the combined treatment (Figs. 2C and D). Adding TPEN to HIV-1 would have removed coordinated Zn2+ from the NC zinc finger domains, allowing 4-VP to react with the newly exposed cysteines and unfold NC zinc fingers. Since NC acts as a nucleic acid chaperone during reverse transcription (Levin et al., 2005; Rein et al., 1998), unfolded zinc finger motifs could account for the observed defect in vDNA synthesis and the loss of infectivity seen after combination treatment.

The defect of reverse transcription, demonstrated by the significant decrease in minus-strand strong-stop DNA, could be caused by inhibition of primer annealing, defects in initiation, or incomplete elongation of vDNA. A defect in annealing of the tRNA primer can be discounted since (i) it would have certainly taken place prior to 4-VP treatment, and (ii) does not require NC zinc fingers (Hargittai et al., 2004) and would not be impaired by their unfolding. On the other hand, NC zinc fingers are important for the initiation and elongation of minus-strand strong-stop DNA synthesis (Huang et al., 1998b; Levin et al., 2005; Rong et al., 1998, 2001). This could account for the defect during initiation or elongation of minus-strand strong-stop DNA synthesis in reverse transcription after 4-VP+TPEN treatment. Of course, if reverse transcription does proceed, these defects would become compounded over the subsequent steps in reverse transcription and this is in fact observed in the more drastic reduction in late vDNA products (Table 1).

However, our results cannot exclude the possibility that proteins other than NC may have been modified by 4-VP. Although it is unlikely that RT is affected (see above), integrase (IN) has six cysteines distributed among its three structural domains: two cysteines in the HHCC zinc finger domain, three in the catalytic domain and one in the C-terminal domain (Engelman et al., 1995). Data presented here showed that 4-VP did not react with Zn2+-bound cysteines within NC, which (provided this holds true for other Zn2+-binding proteins) would preclude IN’s HHCC domain. In the case of the C-terminal cysteine, mutation of this residue to a serine did not impair replication (Bischerour et al., 2003). For the cysteines in the catalytic domain of IN, their modification may be involved in the integration defect observed (Table 1) and this also could account for the modest decrease in viral titer with 4-VP (Fig. 1B). When the cysteines in the catalytic domain are modified by NEM in vitro, IN binds poorly to vDNA (Ellison et al., 1995), although it should be noted that mutation of these cysteines does not affect in vitro enzymatic activity (Zhu et al., 2004).

Genetic studies have shown that mutating cysteines within the catalytic domain of IN can inhibit replication. When replacing the three cysteines in the catalytic domain of IN with serines, only mutation of the third cysteine (Cys130Ser) leads to noninfectious virus (Zhu et al., 2004). However, the phenotype of HIV-1 with Cys130Ser-IN differs from that observed with either the 4-VP or 4-VP+TPEN treatments. In particular, this mutation appears to completely block vDNA synthesis as no minus-strand strong-stop DNA could be detected, even 8 h after infection (Zhu et al., 2004). In contrast, our experiments detected low levels of minus-strand strong-stop at 24 h post-infection with either the 4-VP or 4-VP+TPEN treatments (50% or 6% of wild-type, respectively; Table 1). Interestingly, treatment of HIV-1 with sulfhydryl reagents that are more reactive than 4-VP [e.g. AT-2 (Rossio et al., 1998) or NEM (Morcock et al., 2005)] virtually eliminated minus-strand strong-stop DNA (<0.1% of wild-type), raising the possibility that, with the AT-2 and NEM treatments, derivatized IN may be a factor in defective vDNA synthesis. Another study showed that the Cys130Gly-IN mutant is also noninfectious because of defective vDNA synthesis (Lu et al., 2004a; Petit et al., 1999), but the Cys130Ala-IN mutant replicates at nearly wild-type levels (Lu et al., 2004a). Whether derivatization of IN cysteines would interfere with reverse transcription in the context of chemically inactivated HIV-1 is uncertain. Based on the results of 4-VP+TPEN treatment, chemical modification may not be as detrimental to reverse transcription as the above mentioned point mutations are. Although IN Cys130 clearly influences vDNA synthesis, none of the mutants produce a phenotype matching the inhibition of vDNA integration observed with our 4-VP treatments.

It should also be mentioned that disruption of the zinc finger domain of IN by mutagenesis results in viruses that show defects in reverse transcription after infection. The synthesis of early as well as late reverse transcripts were ~4% of wild-type virus, thus once reverse transcription started in these mutants, it went to completion (Masuda et al., 1995). This phenotype is in contrast to the 4-VP+TPEN results that were obtained in this chemical inactivation study where reverse transcription processivity (i.e. synthesis of late vDNA products) was severely affected.

AT-2 reacts readily with Zn2+-bound cysteines, cross-linking NC and other viral proteins via disulfide bond formation (Chertova et al., 2003; Rossio et al., 1998). This reagent destroys the structure of NC’s zinc fingers, but it is not possible to separate the effects of zinc finger unfolding from protein cross-linking. Using reagents with a different chemistry, covalent addition to cysteine sulfurs, allows better identification of a treatment’s mechanism. Experiments with such reagents, for example NEM (Morcock et al., 2005), 3-nitrosobenzamide (Rice et al., 1993), and 4-VP+TPEN (this study) show that cross-linking NC is not required for chemical inactivation of HIV-1. However, because of their potency, all three of these reagents can react with proteins other than NC. Conclusively identifying the protein(s) responsible for inactivation is therefore difficult. The results presented here showed that 4-VP, a milder reagent that is essentially unreactive with the Zn2+-bound cysteines of NC, was poorly effective unless combined with a Zn2+ chelator. This further supports the conclusion that Zn2+-bound cysteines are critical targets for sulfhydryl reagents and emphasizes the important role of NC zinc fingers in virus inactivation.

Our study focused on viral proteins, but cellular proteins may also be involved in this inactivation mechanism. Viral replication depends on interactions with many host cell proteins (Dvorin and Malim, 2003; Goff, 2007; Trkola, 2004), and HIV-1 virions contain numerous cellular proteins (Chertova et al., 2006; Ott, 2002, in press). Some of these proteins can be expected to react with sulfhydryl reagents, and their derivatization may affect replication by inhibiting enzymatic activities directly or by altering protein interaction surfaces among cellular or viral proteins. However, our HPLC analysis lacks sufficient sensitivity to investigate these less abundant proteins.

As a reagent used to derivatize cysteine for protein analysis, 4-VP is well characterized (Friedman, 2001; Friedman et al., 1970). Use of 4-VP to treat whole virus has not been reported previously, and this reagent’s ability to react selectively with cysteine thiols lacking coordinated Zn2+ may be useful for investigating the role of Zn2+ in protein function within intact virions, generally. In contrast to point mutations, 4-VP treatment allows the examination of virions that have assembled, budded and matured normally, permitting another method for the characterization of early infection events (Thomas and Gorelick, in press).

Materials and methods

Reagents

Chemicals were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO) unless stated otherwise. Stock solutions of 100 mM 4-VP were made in 100 mM HCl; 400 mM GSH was dissolved in Dulbecco’s phosphate buffered saline without Ca2+ or Mg2+ (PBS; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 400 mM NaOH (to neutralize GSH acidity); TPEN was dissolved at 100 mM in absolute ethanol then diluted to 10 mM with PBS. GSH and 4-VP stock solutions were made on the day of use.

Generation of virus stocks

HIV-1 was obtained by transfecting HEK 293T/ clone 17 cells (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA) in 75 cm2 culture flasks (Corning Life Sciences, Lowell, MA) with pNL4-3 (GenBank accession number: AF324493; Adachi et al., 1986) and TransIT293 reagent (Mirus Bio Corporation, Madison, WI) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and cultured overnight. The cells were grown in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 2 mM l-glutamine or 2 mM l-alanyl-l-glutamine, 100 U of penicillin and 100 µg of streptomycin per mL (Invitrogen), and 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Cambrex, Walkersville, MD, or Invitrogen). The next day, cells were rinsed twice with 5 mL of warmed medium then 15 mL of fresh medium was added, and the cells were cultured for 24 h. Culture fluid was clarified by centrifugation for 5 min at 1000 rpm (284 ×g) using a JS-4.2 rotor (Beckman Instruments, Fullerton, CA) and again for 10 min at 4000 rpm (3297 ×g). Virus stocks were used fresh for experiments in Fig. 1. Alternatively, clarified supernatant was layered over 10 mL of 20% (w/v) sucrose in PBS and concentrated by ultracentrifugation at 27,000 rpm (131,453 ×g) for 60 min in an SW28 rotor (Beckman Instruments). Pelleted material was resuspended in 300 µL PBS and centrifuged at 60,000 rpm (156,845 ×g) for 20 min in a TL-100.1 rotor (Beckman Instruments). Supernatant was removed and the virus-containing pellet was stored at −80 °C until HPLC analysis.

Infectivity assay

Viral infectivity was assayed with TZM-bl indicator cells, HeLa cells engineered to express CD4, CXCR4, CCR5 and, under control of HIV-1 LTR promoters, the β-galactosidase and luciferase genes (Derdeyn et al., 2000; Platt et al., 1998; Wei et al., 2002). Cells were grown in DMEM as described for the HEK 293T/ clone 17 cells above. TZM-bl cells were obtained through the NIH AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program, Division of AIDS, NIAID, NIH from Dr. John C. Kappes, Dr. Xiaoyun Wu and Tranzyme Inc. HIV-1 from fresh stocks (see above) was mixed with various concentrations of 4-VP, with or without 50 µM TPEN, and incubated at 37 °C. Samples were collected over a 24 h period of incubation as indicated. GSH at 4 mM was added to quench any unreacted 4-VP, and 100 µM zinc chloride or zinc acetate was added to samples containing TPEN to prevent cellular toxicity. Parallel control incubations of virus stocks with GSH, Zn2+, GSH+ Zn2+ or ethanol at the levels used with the 4-VP and TPEN experiments were also performed to monitor the effects of these reagents on infectivity.

Infectivity assays were performed by seeding white, flat-bottomed 96-well tissue culture-treated plates (Corning Life Sciences) with 1 × 104 cells per well in 100 µL of medium as indicated above. 24 h later, the virus samples, treated as indicated, were diluted three-fold serially over 11 dilutions in medium containing 2 µg/mL hexadimethrine bromide (polybrene; Sigma). Then the medium was removed from the wells and replaced with 100 µL of each dilution, including an undiluted sample, and the plates were incubated for 48 h at 37 °C in 5% CO2. The medium was removed and wells were filled with 150 µL of ice-cold fixative [PBS containing 2% (v/v) glutaraldehyde (Sigma) and 2% (v/v) formaldehyde (Sigma)] and incubated for 5 min. The fixative was removed and the wells filled with 150 µL of ice-cold PBS and allowed to incubate for an additional 5 min. The PBS rinse was then removed and replaced with 100 µL of developer [1.0 mg/mL X-gal (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside; Invitrogen), 7 mM potassium ferricyanide, 7 mM potassium ferrocyanide, and 4 mM MgCl2 in PBS] and the plates were incubated for 3 h at 37 °C. The developer was removed, the plates rinsed 2× with 200 µL PBS (at room temperature) per well, blotted to remove excess liquid, then 200 µL methanol per well was added and immediately discarded and blotted. Plates were allowed to air dry and blue cells in each well were counted using an automated ELISPOT plate reader (Zellnet Consulting, New York, NY). Wells containing medium only were used to determine background levels of blue cells, which were typically <1.6 blue cell forming units per mL (BCFU/mL).

Statistical analysis

Data from Fig. 1B was analyzed using single-factor analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by post hoc Tukey’s test for pairwise comparisons (Zar, 1999; Richardson and Overbaugh, 2005). These analyses were performed on the common (base 10) logarithms of the normalized titer. The probability (p) values obtained are those determined using the Tukey test; probability values less than 0.05 were considered significant.

Reverse transcription

Infection of HOS cells with VSV-G pseudotyped HIV-1 stocks obtained by transfection were performed as described previously (Julias et al., 2001). Briefly, HEK 293T cells were cotransfected by calcium phosphate precipitation with the proviral pNL4-3 Env− plasmid (Ott et al., 1999) and pHCMV-g (Burns et al., 1993), which expresses the VSV-G protein. To reduce contaminating plasmid DNA from the analysis of reverse transcription products, transfected cultures were washed extensively after transfection with PBS containing 1% calf serum as described in Buckman et al. (2003). Two days after transfection, pseudotyped virus was harvested from the culture medium, clarified by low speed centrifugation, passed through a 0.22 µm Millex-GS filter (Millipore, Billerica, MA) and polybrene was added to a final concentration of 2 µg/mL. Virus was then treated for 18 h at 37 °C as described in the Results section. Aliquots were taken from each treatment for exogenous template RT assays as described previously (Gorelick et al., 1990, 1999). HOS cells were then infected with the treated viruses, and 24 h post-infection, cells were harvested from plates and total cellular DNA was extracted using the DNA Blood Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). HOS cells were cultivated at 37 °C in 5% CO2 with the DMEM medium described above except that it contained 5% FBS and 5% calf serum instead of 10% FBS.

Quantitative PCR employed an ABI Prism 7700 sequence detection instrument (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) using the primers, probes, and PCR conditions described previously (Buckman et al., 2003; Thomas et al., 2006). The vDNA copy numbers were normalized for DNA recovery by measuring the copy number of the cellular CCR5 gene (Thomas et al., 2006) and for virus particles by exogenous template RT activity (see above). The completion of early and late steps in reverse transcription was determined by measuring copy numbers of minus-strand strong-stop (R-U5) and plus-strand transfer (R-5′UTR) DNA targets, respectively, after 24 h of infection of the HOS cells with VSV-G pseudotyped HIV-1 as described (Buckman et al., 2003). The formation of proviruses was measured with an Alu-LTR assay described by Butler et al. (2001), modified as described in Thomas et al. (2006).

HPLC

Whole virus lysates and wild-type recombinant NC, prepared as described in Carteau et al. (1999) or Wu et al. (1996) were analyzed by microcapillary high-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC). Pelleted virus from HIV-1 pNL4-3 transfections (described above) was dissolved in 60 µL HPLC lysis buffer [6.2 M guanidine–HCl (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL), 1 M NaCl and 2% (v/v) β-mercaptoethanol in 10 mM Tris buffer, pH 8.5] and reduced for 1 h at room temperature; 10 µL aliquots were stored at −80 °C until used. Reverse phase HPLC was performed at a flow rate of 10 µL/min in a 500 µm × 100 mm column packed with 10 µm Poros R2/H poly(styrene-divinyl-benzene) beads (Applied Biosystems) using a MicroPro pumping system (Eldex Laboratories, Napa, CA) with an Agilent 1100 diode-array detector (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). Absorbance was recorded at 206, 255, and 280 nm. Column temperature was maintained at 30 °C. Solvent A was 0.1% (v/v) trifluoroacetic acid and during whole viral lysate analysis, a gradient of increasing solvent B (0.1% (v/v) trifluoroacetic acid in 90% (v/v) acetonitrile) was added as follows: 5% B, 0–5 min; 5–12% B, 15 min; 12–37% B, 92 min; 37–50% B, 212 min; 50–66% B, 232 min; 66–100% B, 242 min; and 100% B, 253 min. For experiments with purified NC, the gradient of increasing solvent B in A was: 5–32% B, 60 min; 32% B, 5 min; 32–67% B, 5 min; and 67% B, 5 min. HPLC peaks corresponding to HIV-1NL4-3 p1 (SP2) and p6 Gag proteins, which lack cysteine (Henderson et al., 1988), were used as internal standards to compensate for variation in the amount of protein and gradient fluctuations caused by back-pressure variations between chromatographic runs. The data were normalized to equal time between p1 and p6 then aligned using a peak between these Gag proteins, p6f (Henderson et al., 1988; N-terminal fragment of p6, a.a. 1–36; analyzed with a Procise model 494 protein sequencer, Applied Biosystems). Peak height was normalized to p6f, and baseline was adjusted to a normalized scale. A255/A280 ratios were calculated from peak height above baseline.

Mass spectrometry

HPLC fractions from purified NC experiments were analyzed by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry using a Kratos Kompact Probe MALDI mass spectrometer (Kratos Analytical, Chestnut Ridge, NY) as described previously (Morcock et al., 2005). Bovine insulin (5734.6 Da) and ubiquitin (8565.9 Da) were used as molecular mass standards.

Acknowledgments

We thank Tracy Gagliardi, Laurie Queen, and Teresa Shatzer for technical assistance. We also wish to thank William Bosche for adaptation of the TZM-bl assay into a 96-well format. Parts of this study were performed by D.M. in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a M.S. degree from the Biomedical Science Program, Department of Biology, Hood College, Frederick, MD. This project has been funded in whole or in part with federal funds from the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, under contract N01-CO-12400. The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. Government.

References

- Adachi A, Gendelman HE, Koenig S, Folks T, Willey R, Rabson A, Martin MA. Production of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome-associated retrovirus in human and nonhuman cells transfected with an infectious molecular clone. J. Virol. 1986;59:284–291. doi: 10.1128/jvi.59.2.284-291.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderegg G, Hubmann E, Podder NG, Wenk F. Pyridinderivate als komplexbildner. XI. Die thermodynamik der metallkomplexbildung mit bis-, tris- und tetrakis[(2-pyridyl)methyl]-aminen. Helv. Chim. Acta. 1977;60:123–140. [Google Scholar]

- Arslan P, Di Virgilio F, Beltrame M, Tsien RY, Pozzan T. Cytosolic Ca2+ homeostasis in Ehrlich and Yoshida carcinomas. A new, membrane-permeant chelator of heavy metals reveals that these ascites tumor cell lines have normal cytosolic free Ca2+ J. Biol. Chem. 1985;260:2719–2727. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg JM. Potential metal-binding domains in nucleic acid binding proteins. Science. 1986;232:485–487. doi: 10.1126/science.2421409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bess JW, Jr, Powell PJ, Issaq HJ, Schumack L, Grimes MK, Henderson LE, Arthur LO. Tightly bound zinc in human immunodeficiency virus type 1, human T-cell leukemia virus type 1, and other retroviruses. J. Virol. 1992;66:840–847. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.2.840-847.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bischerour J, Leh H, Deprez E, Brochon JC, Mouscadet JF. Disulfide-linked integrase oligomers involving C280 residues are formed in vitro and in vivo but are not essential for human immunodeficiency virus replication. J. Virol. 2003;77:135–141. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.1.135-141.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckman JS, Bosche WJ, Gorelick RJ. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 nucleocapsid Zn2+ fingers are required for efficient reverse transcription, initial integration processes, and protection of newly synthesized viral DNA. J. Virol. 2003;77:1469–1480. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.2.1469-1480.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns JC, Friedmann T, Driever W, Burrascano M, Yee JK. Vesicular stomatitis virus G glycoprotein pseudotyped retroviral vectors: concentration to very high titer and efficient gene transfer into mammalian and nonmammalian cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1993;90:8033–8037. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.17.8033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler SL, Hansen MS, Bushman FD. A quantitative assay for HIV DNA integration in vivo. Nat. Med. 2001;7:631–634. doi: 10.1038/87979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carteau S, Batson SC, Poljak L, Mouscadet JF, de Rocquigny H, Darlix JL, Roques BP, Kas E, Auclair C. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 nucleocapsid protein specifically stimulates Mg2+-dependent DNA integration in vitro. J. Virol. 1997;71:6225–6229. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.8.6225-6229.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carteau S, Gorelick RJ, Bushman FD. Coupled integration of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 cDNA ends by purified integrase in vitro: stimulation by the viral nucleocapsid protein. J. Virol. 1999;73:6670–6679. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.8.6670-6679.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chance MR, Sagi I, Wirt MD, Frisbie SM, Scheuring E, Chen E, Bess JW, Jr, Henderson LE, Arthur LO, South TL, Perez-Alvarado G, Summers MF. Extended X-ray absorption fine structure studies of a retrovirus: equine infectious anemia virus cysteine arrays are coordinated to zinc. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1992;89:10041–10045. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.21.10041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chertova E, Chertov O, Coren LV, Roser JD, Trubey CM, Bess JW, Jr, Sowder RC, 2nd, Barsov E, Hood BL, Fisher RJ, Nagashima K, Conrads TP, Veenstra TD, Lifson JD, Ott DE. Proteomic and biochemical analysis of purified human immunodeficiency virus type 1 produced from infected monocyte-derived macrophages. J. Virol. 2006;80:9039–9052. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01013-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chertova E, Crise BJ, Morcock DR, Bess JW, Jr, Henderson LE, Lifson JD. Sites, mechanism of action and lack of reversibility of primate lentivirus inactivation by preferential covalent modification of virion internal proteins. Curr. Mol. Med. 2003;3:265–272. doi: 10.2174/1566524033479889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chertova EN, Kane BP, McGrath C, Johnson DG, Sowder RC, 2nd, Arthur LO, Henderson LE. Probing the topography of HIV-1 nucleocapsid protein with the alkylating agent N-ethylmaleimide. Biochemistry. 1998;37:17890–17897. doi: 10.1021/bi980907y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covey SN. Amino acid sequence homology in gag region of reverse transcribing elements and the coat protein gene of cauliflower mosaic virus. Nucleic Acids Res. 1986;14:623–633. doi: 10.1093/nar/14.2.623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Guzman RN, Wu ZR, Stalling CC, Pappalardo L, Borer PN, Summers MF. Structure of the HIV-1 nucleocapsid protein bound to the SL3 Y-RNA recognition element. Science. 1998;279:384–388. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5349.384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derdeyn CA, Decker JM, Sfakianos JN, Wu X, O’Brien WA, Ratner L, Kappes JC, Shaw GM, Hunter E. Sensitivity of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 to the fusion inhibitor T-20 is modulated by coreceptor specificity defined by the V3 loop of gp120. J. Virol. 2000;74:8358–8367. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.18.8358-8367.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dvorin JD, Malim MH. Intracellular trafficking of HIV-1 cores: journey to the center of the cell. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2003;281:179–208. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-19012-4_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellison V, Gerton J, Vincent KA, Brown PO. An essential interaction between distinct domains of HIV-1 integrase mediates assembly of the active multimer. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:3320–3326. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.7.3320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engelman A, Englund G, Orenstein JM, Martin MA, Craigie R. Multiple effects of mutations in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 integrase on viral replication. J. Virol. 1995;69:2729–2736. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.5.2729-2736.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher RJ, Fivash MJ, Stephen AG, Hagan NA, Shenoy SR, Medaglia MV, Smith LR, Worthy KM, Simpson JT, Shoemaker R, McNitt KL, Johnson DG, Hixson CV, Gorelick RJ, Fabris D, Henderson LE, Rein A. Complex interactions of HIV-1 nucleocapsid protein with oligonucleotides. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:472–484. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher RJ, Rein A, Fivash M, Urbaneja MA, Casas-Finet JR, Medaglia M, Henderson LE. Sequence-specific binding of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 nucleocapsid protein to short oligonucleotides. J. Virol. 1998;72:1902–1909. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.3.1902-1909.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman M. Application of the S-pyridylethylation reaction to the elucidation of the structures and functions of proteins. J. Protein Chem. 2001;20:431–453. doi: 10.1023/a:1012558530359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman M, Krull LH, Cavins JF. The chromatographic determination of cystine and cysteine residues in proteins as S-b-(4-pyridylethyl) cysteine. J. Biol. Chem. 1970;245:3868–3871. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goff SP. Host factors exploited by retroviruses. Nat. Rev., Microbiol. 2007;5:253–263. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorelick RJ, Chabot DJ, Rein A, Henderson LE, Arthur LO. The two zinc fingers in the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 nucleocapsid protein are not functionally equivalent. J. Virol. 1993;67:4027–4036. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.7.4027-4036.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorelick RJ, Gagliardi TD, Bosche WJ, Wiltrout TA, Coren LV, Chabot DJ, Lifson JD, Henderson LE, Arthur LO. Strict conservation of the retroviral nucleocapsid protein zinc finger is strongly influenced by its role in viral infection processes: characterization of HIV-1 particles containing mutant nucleocapsid zinc-coordinating sequences. Virology. 1999;256:92–104. doi: 10.1006/viro.1999.9629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorelick RJ, Henderson LE, Hanser JP, Rein A. Point mutants of Moloney murine leukemia virus that fail to package viral RNA: evidence for specific RNA recognition by a “zinc finger-like” protein sequence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1988;85:8420–8424. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.22.8420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorelick RJ, Nigida SM, Jr, Bess JW, Jr, Arthur LO, Henderson LE, Rein A. Noninfectious human immunodeficiency virus type 1 mutants deficient in genomic RNA. J. Virol. 1990;64:3207–3211. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.7.3207-3211.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo J, Wu T, Kane BF, Johnson DG, Henderson LE, Gorelick RJ, Levin JG. Subtle alterations of the native zinc finger structures have dramatic effects on the nucleic acid chaperone activity of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 nucleocapsid protein. J. Virol. 2002;76:4370–4378. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.9.4370-4378.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hargittai MR, Gorelick RJ, Rouzina I, Musier-Forsyth K. Mechanistic insights into the kinetics of HIV-1 nucleocapsid protein-facilitated tRNA annealing to the primer binding site. J. Mol. Biol. 2004;337:951–968. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.01.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hathout Y, Fabris D, Han MS, Sowder RC, II, Henderson LE, Fenselau C. Characterization of intermediates in the oxidation of zinc fingers in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 nucleocapsid protein p7. Drug Metab. Dispos. 1996;24:1395–1400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson LE, Copeland TD, Sowder RC, Schultz AM, Oroszlan S. Analysis of Proteins and Peptides Purified from Sucrose Gradient Banded HTLV-III, Human Retroviruses, Cancer and AIDS: Approaches to Prevention and Therapy. Alan R. Liss, Inc. 1988:135–147. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson LE, Copeland TD, Sowder RC, II, Smythers GW, Oroszlan S. Primary structure of the low molecular weight nucleic acid-binding proteins of murine leukemia viruses. J. Biol. Chem. 1981;256:8400–8406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang M, Maynard A, Turpin JA, Graham L, Janini GM, Covell DG, Rice WG. Anti-HIV agents that selectively target retroviral nucleocapsid protein zinc fingers without affecting cellular zinc finger proteins. J. Med. Chem. 1998a;41:1371–1381. doi: 10.1021/jm9708543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y, Khorchid A, Gabor J, Wang J, Li X, Darlix JL, Wainberg MA, Kleiman L. The role of nucleocapsid and U5 stem/A-rich loop sequences in tRNA3Lys genomic placement and initiation of reverse transcription in human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J. Virol. 1998b;72:3907–3915. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.5.3907-3915.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Julias JG, Ferris AL, Boyer PL, Hughes SH. Replication of phenotypically mixed human immunodeficiency virus type 1 virions containing catalytically active and catalytically inactive reverse transcriptase. J. Virol. 2001;75:6537–6546. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.14.6537-6546.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee BM, De Guzman RN, Turner BG, Tjandra N, Summers MF. Dynamical behavior of the HIV-1 nucleocapsid protein. J. Mol. Biol. 1998;279:633–649. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.1766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin JG, Guo J, Rouzina I, Musier-Forsyth K. Nucleic acid chaperone activity of HIV-1 nucleocapsid protein: critical role in reverse transcription and molecular mechanism. Prog. Nucleic Acid Res. Mol. Biol. 2005;80:217–286. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6603(05)80006-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lifson JD, Rossio JL, Piatak M, Jr, Bess J, Jr, Chertova E, Schneider DK, Coalter VJ, Poore B, Kiser RF, Imming RJ, Scarzello AJ, Henderson LE, Alvord WG, Hirsch VM, Benveniste RE, Arthur LO. Evaluation of the safety, immunogenicity, and protective efficacy of whole inactivated simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) vaccines with conformationally and functionally intact envelope glycoproteins. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrov. 2004;20:772–787. doi: 10.1089/0889222041524661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu R, Limon A, Devroe E, Silver PA, Cherepanov P, Engelman A. Class II integrase mutants with changes in putative nuclear localization signals are primarily blocked at a postnuclear entry step of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 replication. J. Virol. 2004a;78:12735–12746. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.23.12735-12746.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu W, Arraes LC, Ferreira WT, Andrieu JM. Therapeutic dendritic-cell vaccine for chronic HIV-1 infection. Nat. Med. 2004b;10:1359–1365. doi: 10.1038/nm1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masuda T, Planelles V, Krogstad P, Chen IS. Genetic analysis of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 integrase and the U3 att site: unusual phenotype of mutants in the zinc finger-like domain. J. Virol. 1995;69:6687–6696. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.11.6687-6696.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maynard AT, Huang M, Rice WG, Covell DG. Reactivity of the HIV-1 nucleocapsid protein p7 zinc finger domains from the perspective of density-functional theory. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1998;95:11578–11583. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.20.11578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mély Y, De Rocquigny H, Morellet N, Roques BP, Gérard D. Zinc binding to the HIV-1 nucleocapsid protein: a thermodynamic investigation by fluorescence spectroscopy. Biochemistry. 1996;35:5175–5182. doi: 10.1021/bi952587d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morcock DR, Thomas JA, Gagliardi TD, Gorelick RJ, Roser JD, Chertova EN, Bess JW, Jr, Ott DE, Sattentau QJ, Frank I, Pope M, Lifson JD, Henderson LE, Crise BJ. Elimination of retroviral infectivity by N-ethylmaleimide with preservation of functional envelope glycoproteins. J. Virol. 2005;79:1533–1542. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.3.1533-1542.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ott DE. Potential roles of cellular proteins in HIV-1. Rev. Med. Virol. 2002;12:359–374. doi: 10.1002/rmv.367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ott DE. Cellular proteins detected in HIV-1. Rev. Med. Virol. doi: 10.1002/rmv.570. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ott DE, Chertova EN, Busch LK, Coren LV, Gagliardi TD, Johnson DG. Mutational analysis of the hydrophobic tail of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 p6Gag protein produces a mutant that fails to package its envelope protein. J. Virol. 1999;73:19–28. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.1.19-28.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petit C, Schwartz O, Mammano F. Oligomerization within virions and subcellular localization of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 integrase. J. Virol. 1999;73:5079–5088. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.6.5079-5088.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Platt EJ, Wehrly K, Kuhmann SE, Chesebro B, Kabat D. Effects of CCR5 and CD4 cell surface concentrations on infections by macro-phagetropic isolates of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J. Virol. 1998;72:2855–2864. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.4.2855-2864.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poljak L, Batson SM, Ficheux D, Roques BP, Darlix JL, Kas E. Analysis of NCp7-dependent activation of HIV-1 cDNA integration and its conservation among retroviral nucleocapsid proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 2003;329:411–421. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00472-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rein A, Henderson LE, Levin JG. Nucleic-acid-chaperone activity of retroviral nucleocapsid proteins: significance for viral replication. Trends Biochem. Sci. 1998;23:297–301. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(98)01256-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rein A, Ott DE, Mirro J, Arthur LO, Rice W, Henderson LE. Inactivation of murine leukemia virus by compounds that react with the zinc finger in the viral nucleocapsid protein. J. Virol. 1996;70:4966–4972. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.8.4966-4972.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice WG, Schaeffer CA, Harten B, Villinger F, South TL, Summers MF, Henderson LE, Bess JW, Jr, Arthur LO, McDougal JS, Orloff SL, Mendeleyev J, Kun E. Inhibition of HIV-1 infectivity by zinc-ejecting aromatic C-nitroso compounds. Nature. 1993;361:473–475. doi: 10.1038/361473a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice WG, Supko JG, Malspeis L, Buckheit, Robert W, Clanton D, Bu M, Graham L, Schaeffer CA, Turpin JA, Domagala J, Gogliotti R, Bader JP, Halliday SM, Coren L, II, R.C.S., Arthur LO, Henderson LE. Inhibitors of HIV nucleocapsid protein zinc fingers as candidates for the treatment of AIDS. Science. 1995;270:1194–1197. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5239.1194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson BA, Overbaugh J. Basic statistical considerations in virological experiments. J. Virol. 2005;79:669–676. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.2.669-676.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rong L, Liang C, Hsu M, Guo X, Roques BP, Wainberg MA. HIV-1 nucleocapsid protein and the secondary structure of the binary complex formed between tRNALys.3 and viral RNA template play different roles during initiation of (−) strand DNA reverse transcription. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:47725–47732. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105124200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rong L, Liang C, Hsu M, Hsu M, Kleiman L, Petitjean P, de Rocquigny H, Roques BP, Wainberg MA. Roles of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 nucleocapsid protein in annealing and initiation versus elongation in reverse transcription of viral negative-strand strong-stop DNA. J.Virol. 1998;72:9353–9358. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.11.9353-9358.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossio JL, Esser MT, Suryanarayana K, Schneider DK, Bess JW, Jr, Vasquez GM, Wiltrout TA, Chertova E, Grimes MK, Sattentau Q, Arthur LO, Henderson LE, Lifson JD. Inactivation of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infectivity with preservation of conformational and functional integrity of virion surface proteins. J. Virol. 1998;72:7992–8001. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.10.7992-8001.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Summers MF, Henderson LE, Chance MR, Bess JW, Jr, South TL, Blake PR, Sagi I, Perez-Alvarado G, II, R.C.S., Hare D, Arthur LO. Nucleocapsid zinc fingers detected in retroviruses: EXAFS studies of intact viruses and the solution-state structure of the nucleocapsid protein from HIV-1. Protein Sci. 1992;1:563–574. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560010502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanchou V, Decimo D, Péchoux C, Lener D, Rogemond V, Berthoux L, Ottmann M, Darlix JL. Role of the N-terminal zinc finger of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 nucleocapsid protein in virus structure and replication. J. Virol. 1998;72:4442–4447. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.5.4442-4447.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas JA, Gagliardi TD, Alvord WG, Lubomirski M, Bosche WJ, Gorelick RJ. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 nucleocapsid zinc-finger mutations cause defects in reverse transcription and integration. Virology. 2006;353:41–51. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas JA, Gorelick RJ. Nucleocapsid protein function in early infection processes. Virus Res. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2007.12.006. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Topol IA, McGrath C, Chertova E, Dasenbrock C, Lacourse WR, Eissenstat MA, Burt SK, Henderson LE, Casas-Finet JR. Experimental determination and calculations of redox potential descriptors of compounds directed against retroviral zinc fingers: implications for rational drug design. Protein Sci. 2001;10:1434–1445. doi: 10.1110/ps.52601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trkola A. HIV–host interactions: vital to the virus and key to its inhibition. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2004;7:555–559. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2004.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tummino PJ, Scholten JD, Harvey PJ, Holler TP, Maloney L, Gogliotti R, Domagala J, Hupe D. The in vitro ejection of zinc from human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) type 1 nucleocapsid protein by disulfide benzamides with cellular anti-HIV activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1996;93:969–973. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.3.969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogt VM. Retroviral virions and genomes. In: Coffin JM, Hughes SH, Varmus HE, editors. “Retroviruses”. Plainview, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1997. pp. 27–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei X, Decker JM, Liu H, Zhang Z, Arani RB, Kilby JM, Saag MS, Wu X, Shaw GM, Kappes JC. Emergence of resistant human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in patients receiving fusion inhibitor (T-20) monotherapy. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2002;46:1896–1905. doi: 10.1128/AAC.46.6.1896-1905.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu W, Henderson LE, Copeland TD, Gorelick RJ, Bosche WJ, Rein A, Levin JG. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 nucleocapsid protein reduces reverse transcriptase pausing at a secondary structure near the murine leukemia virus polypurine tract. J. Virol. 1996;70:7132–7142. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.10.7132-7142.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zar JH. Biostatistical Analysis. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, Inc; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu K, Dobard C, Chow SA. Requirement for integrase during reverse transcription of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 and the effect of cysteine mutations of integrase on its interactions with reverse transcriptase. J. Virol. 2004;78:5045–5055. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.10.5045-5055.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]