Abstract

Monitoring gaze shifts is important for social interactions. The direction of gaze can reveal intentions and help to predict future actions. Here we examined whether behavioural and neural responses to gaze shifts were modulated by the social context of the gaze shift in two linked experiments. Two faces were presented, one gazing directly at the subject (the ‘social’ face) and one with averted gaze (the ’unsocial’ face). One face then made a gaze shift that was either towards a visible target (’correct’) or towards another location in space (’incorrect’). Both behavioural and neural responses to gaze shifts were modulated by the social context and the goal directedness of the gaze shift. Reaction times were significantly faster in response to ’correct’ and ‘social’ compared with ’incorrect’ and ’unsocial’ gaze shifts, respectively. Using functional magnetic resonance imaging, we found significantly greater activation in the parieto-frontal attentional network, and in some parts of the posterior superior temporal sulcus, in response to ‘incorrect’ and ’unsocial’ compared with ’incorrect’ and ‘social’ gaze shifts, respectively. Conversely, we found greater activation in the medial prefrontal cortex and precuneus in response to ’correct’ and ‘social’ compared with ’incorrect’ and ’unsocial’ gaze shifts. This activity may reflect the experience of joint attention associated with these gaze shifts.

Keywords: fMRI, gaze, social, attention

INTRODUCTION

Gaze is an important social stimulus that indicates the direction of attention of an individual. This information is particularly important for social interactions as the direction of attention of other individuals can reveal their intentions and future actions. Humans are extremely sensitive to the direction of gaze of other people (Gibson and Pick, 1963) and automatically direct spatial attention in the direction of gaze (Driver et al., 1999; Langton and Bruce, 1999). Such sensitivity to gaze direction (Hood et al., 1998) is thought to be critical to the development of theory of mind (Baron-Cohen, 1995).

Gaze perception activates a parieto-frontal network of regions, plus the occipito-temporal cortex, including the superior temporal sulcus (STS) (Grosbras et al., 2005). This parieto-frontal network is also activated by execution of eye movements and by shifts of spatial attention (Nobre et al., 1997; Corbetta et al., 1998; Kato et al., 2001; Grosbras et al., 2005), suggesting that attentional and oculomotor processes are closely related at the neuronal level (Corbetta et al., 1998). Indeed, the premotor theory of attention proposes that covert shifts of attention represent planned eye movements that are not executed (Rizzolatti et al., 1987). Activation of common areas by eye movements and gaze perception might therefore indicate the existence of an oculomotor ‘mirror system’, which could account for automatic reorienting of spatial attention in response to gaze (Driver et al., 1999; Langton and Bruce, 1999; Grosbras et al., 2005).

The human STS is also activated by gaze perception (Puce et al., 1998; Wicker et al., 1998; Hoffman and Haxby, 2000; Hooker et al., 2003; Pelphrey et al., 2003; Grosbras et al., 2005). Activity in the STS is prolonged by a perceived mismatch between a gaze shift and its supposed target, if the gaze shift occurs in the presence of a visible target (Pelphrey et al., 2003) and the same is true of hand actions (Pelphrey et al., 2004a). This suggests that the STS is sensitive to the goal directedness or intentionality of actions, and is involved in monitoring and predicting the actions of others (Pelphrey et al., 2003; Ramnani and Miall, 2004; Saxe, 2006).

Here we sought to examine whether the neural response to gaze shifts was modulated by the social context of the gaze shift. In everyday life, it is intuitively apparent that whether an individual is socially interacting with us (or not) will affect the significance of their gaze direction and thus the importance of determining their direction of gaze. We therefore modified an established gaze perception paradigm (Pelphrey et al., 2003) to include a social context, and studied behavioural responses and brain activity in two linked behavioural and functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) experiments.

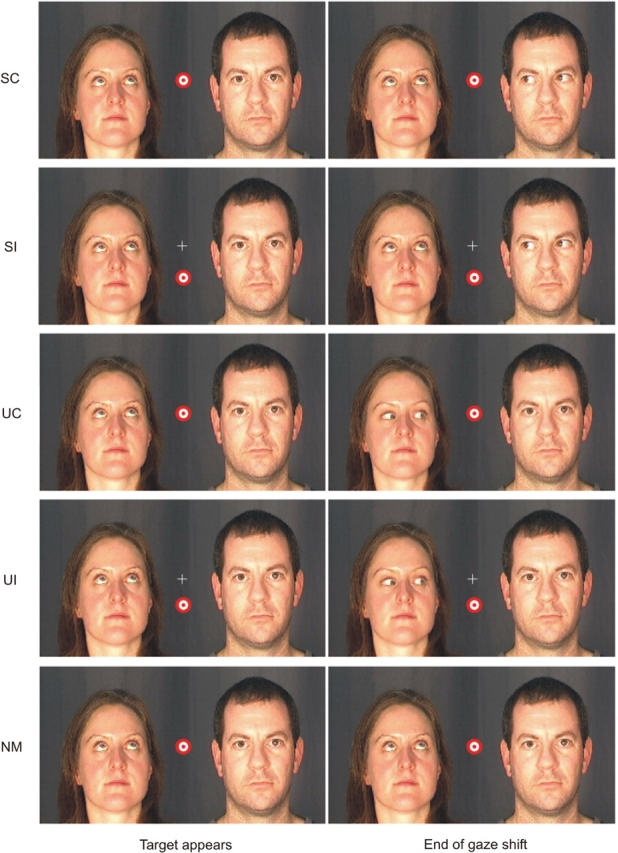

On each experimental trial, two faces were always presented on screen either side of central fixation; but only one was socially relevant (Figure 1). This was achieved by ensuring that at the start of each trial, one face gazed directly at the subject (the ‘social’ face) while the other's gaze was averted (the ‘unsocial’ face). Direct gaze is a more salient and engaging stimulus than averted gaze (Gibson and Pick, 1963; Von Grunau and Anston, 1995) and can signal, amongst other types of social interaction, the intention to communicate (Kampe et al., 2003). A target then appeared on screen (Pelphrey et al., 2003) between the two faces, and one of the faces made a gaze shift. This gaze shift could be either towards the target, which we termed a ‘correct’ gaze shift, or towards another location in space which we termed an ‘incorrect’ gaze shift. The gaze shift could be made by either the ‘social’ or the ‘unsocial’ face, so we could thus manipulate the social context in which a gaze shift occurred while controlling for the presence of direct and averted gaze per se. Two factors were thus modulated independently in a factorial design: the social context of the gaze shift, and the goal directedness of that gaze shift. To ensure that our results could not be due to differences in eye movements between conditions, subjects were instructed to fixate centrally throughout and their eye movements were monitored with long-range eye tracking.

Fig. 1.

The five experimental conditions.

We hypothesised that the neural response to gaze shifts would be modulated by the feeling of involvement in a social interaction and the perceived communicative intention of the gaze shift. Such a feeling of personal involvement in a social interaction, mediated by direct vs averted gaze, has previously been shown to modulated activity in the medial prefrontal cortex (MPFC) (Schilbach et al., 2006). In addition to seeing increased activation in the STS to ‘incorrect’ compared with ‘correct’ gaze shifts (Pelphrey et al., 2003), we hypothesised that the communicative intent attributed to the ‘social’ face would give rise to the expectation that this face would make a gaze shift, leading to greater STS activation, when this prediction is violated by the ‘unsocial’ face making the gaze shift, if, as has been proposed, the STS is indeed involved in predicting actions (Ramnani and Miall, 2004) and shows greater activation when these predictions are violated (Pelphrey et al., 2003). We also expected to see increased activation in the parieto-frontal attentional network in response to the ‘incorrect’ and ‘unsocial’ conditions compared with the ‘correct’ and ‘social’ conditions, respectively, due to an additional shifting of the subject's attention from the target (which initially attracts the subject's attention) to another location by the gaze shift in the ‘incorrect’ but not the ‘correct’ condition, and from the ‘social’ face (whose direct gaze initially engages the subject) to the ‘unsocial’ face by the eye movement in the ‘unsocial’ but not the ‘social’ condition. We also hypothesised that the salience of the social face might lead to enhancement of the effects of goal directedness (i.e. ‘correct’ vs ‘incorrect’ gaze shifts) on the response to gaze shifts, due to greater attention being paid to the gaze shifts made by the social face.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Behavioural experiment

Prior to scanning, we conducted a behavioural experiment to verify that the face with direct gaze was indeed more engaging than the face with averted gaze, and to see whether the subject's spatial attention was attracted to the target prior to being shifted in the direction of gaze.

Subjects

Ten normal volunteers (five male and five female, age 18–41 years, mean = 27.1, s.d. = 8.2) gave written informed consent to participate in the study, which was approved by the Institute of Neurology and National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery Joint Ethics Committee.

Stimuli and paradigm

Visual stimuli were presented on a computer screen, using Cogent (http://www.vislab.ucl.ac.uk/Cogent/). Stimuli consisted of video clips of two people, one male and one female, presented side by side, from the neck upwards. One of the faces, the ‘social’ face, looked directly towards the subject, and the other face, the ‘unsocial’ face had its gaze averted. The faces appeared on screen at the start of each trial, and after 1.5 s, a target, consisting of a red and white flickering bull's eye, appeared at one of three possible locations between the two faces, within each character's field of view; at eye level above eye level and below eye level. 500ms after target appearance, one of the faces shifted their gaze towards the target, a ‘correct’ gaze shift, or towards one of the two other locations at which the target could have but did not appear, an ‘incorrect’ gaze shift.

The experiment thus consisted of four conditions (Figure 1):

SC: ‘Social’ face makes a ‘correct’ gaze shift to target and

SI: ‘Social’ face makes an ‘incorrect’ gaze shift to empty location,

UC: ‘Unsocial’ face makes a ‘correct’ gaze shift to target and

UI: ‘Unsocial’ face makes an ‘incorrect’ gaze shift to empty location.

The gaze shifts lasted 100ms; the eyes then remained in their final positions, and the target remained on screen until the end of the trial. The size of the gaze shift made by the face was the same for each condition, and consisted of a 71° shift in the direction of gaze of the face, either from the centre to the side for the ‘social’ face or between different locations around the face for the ‘unsocial’ face. A small white fixation cross was presented in the centre of the screen (at eye level between the two faces) throughout the experiment, and subjects were instructed to fixate this cross.

Subjects were instructed to indicate whether the face which made the gaze shift looked at the target or not by pressing a button. They were told to respond as quickly as possible and reaction times were recorded. The next trial began 1 s after the subject pressed the button.

Each trial type was presented 48 times, with a total of 192 trials being presented to each subject, and trial order was randomised.

Statistical analysis

The mean of the reaction times was calculated for each condition for each subject, and a repeated measures ANOVA was used to examine the effects of sociability of the face making the gaze shift (‘social’ face vs ‘unsocial’ face), and direction of the gaze shift (‘correct’ vs ‘incorrect’ gaze shifts) on reaction times.

fMRI experiment

Subjects

Twelve normal volunteers (four male and eight female, age 18–40 years, mean = 24.73, s.d. = 6.42) gave written informed consent to participate in the study, which was approved by the Institute of Neurology and National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery Joint Ethics Committee.

Stimuli and paradigm

Visual stimuli were presented on a screen viewed by a mirror mounted on the head coil, using Cogent (http://www.vislab.ucl.ac.uk/Cogent/). The same stimuli were used as in the behavioural experiment (see above), plus an additional baseline condition in which neither face made a gaze shift (NM) (Figure 1).

As in the behavioural study, the gaze shifts lasted 100 ms. The eyes then remained in their final positions, and the target remained on screen until the end of the trial 2 s later. Trials were separated by a 4 s interval during which a blank screen was presented. A small white fixation cross was presented in the centre of the screen (at eye level between the two faces) throughout the experiment and subjects were instructed to fixate this cross. Subjects were instructed to indicate whether the face which made the gaze shift looked at the target or not, or whether there had been no gaze shift, by pressing a button. They were instructed to wait until the appearance of the blank screen at the end of the trial before answering the question.

Each trial type was presented 48 times, with a total of 240 trials being presented to each subject, and trial order was randomised.

Functional imaging

A 3T Siemens ALLEGRA system (Siemens, Erlangen) was used to acquire gradient-echo echo-planar T2*-weighted images with blood oxygenation level dependent (BOLD) contrast. Each volume consisted of forty 3mm axial slices with in-plane resolution of 3 × 3 mm positioned to cover the whole brain with a TR of 2.6 s. Imaging was performed in one scanning run of 780 volumes. In each scanning run, six image volumes preceding presentation of the experimental conditions were discarded to allow for T1 equilibration effects. Eye movements were monitored continually during scanning using an ASL Eye-Tracking System (Applied Science Laboratories, Bedford) with remote optics (Model 504, sampling rate = 60 Hz) that was custom-adapted for use in the scanner. Finally, a T1-weighted anatomical image was acquired from each subject.

Statistical analysis of fMRI data

Data were analysed using Statistical Parametric Mapping software (SPM2; Wellcome Department of Imaging Neuroscience, www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm). The initial six volumes were discarded, and subsequent image volumes then realigned (Friston et al., 1995), spatially normalised (Ashburner and Friston, 1999) to the standard space defined by the Montreal Neurological Institute template (Mazziotta et al., 1995) and smoothed with a Gaussian kernel of 6 mm full-width half maximum. Voxels activated during the experiment were identified using a general linear model that included the five experimental conditions. The gaze shifts were modelled as events with duration 120 ms, and the no gaze shift condition was modelled as an event with 120 ms duration at the time a gaze shift would normally have occurred. High-pass filtering removed low-frequency drifts in signal, and global changes were removed by proportional scaling. Each component of the model served as a regressor in a multiple regression analysis. The resulting parameter estimates for each regressor at each voxel were then entered into a second level analysis where subject served as a random effect in a within-subjects ANOVA. The main effects and interactions between conditions were then specified by appropriately weighted linear contrasts and determined using the t-statistic on a voxel-by-voxel basis.

Statistical analysis of eye-movement data

Eye-movement data were analysed using custom-made Matlab scripts to ensure that subjects maintained fixation and that there were no differences in eye movements between conditions. The total length of scan path was compared across conditions. We also compared the mean distance between the eye position at each time point and the average eye position (a measure of fixation) across conditions.

We also compared average eye position during each trial for different target locations, for the different locations (left or right side of the screen) of the ‘social’ face, whether or not it made the gaze shift, for the different locations (left or right side of the screen) of the face making the gaze shift, whether it was the ‘social’ or ‘unsocial’ face, and for the different end positions of the gaze shift.

RESULTS

Behavioural experiment

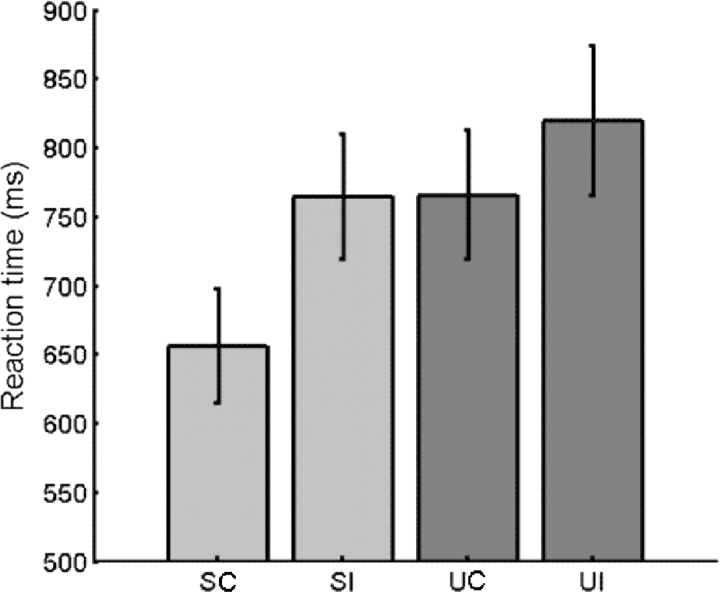

Reaction times were significantly faster (F(1,9) = 44.0, P < 0.000) when the gaze shifts were made by the ‘social’ face (mean RT = 710 ms) rather than the ‘unsocial’ face (mean RT = 793 ms). In addition, reaction times were significantly faster (F(1,9) = 18.1, P = 0.002) for ‘correct’ gaze shifts (mean RT = 711 ms) compared with ‘incorrect’ gaze shifts (mean RT = 792 ms; Figure 2). There appeared to be an interaction between direction of gaze shift (‘correct’ vs ‘incorrect’) and face making the gaze shift (‘social’ vs ‘unsocial’), such that the effect of direction on reaction time is greater for the ‘social’ face than for the ‘unsocial’ face, and this interaction trended towards significance (F(1,9) = 4.08, P = 0.074).

Fig. 2.

Mean reaction times for detecting whether a gaze shift was made to the target or not.

Functional imaging experiment

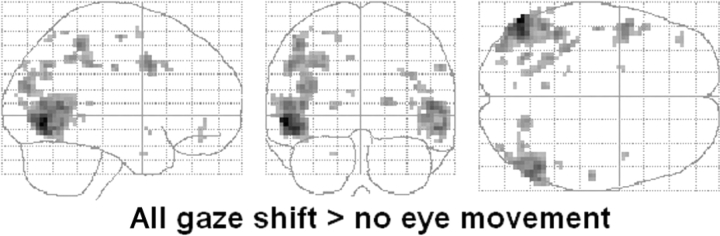

All types of gaze shift minus no movement control

The main effect of observing gaze shifts, i.e. all conditions with a gaze shift − no eye movement condition [thresholded at P < 0.05 FDR (false discovery rate)-corrected], revealed bilateral activation in a large region of the occipito-temporal cortex from the posterior horizontal segment of the STS to the inferior occipital sulcus (Figure 3). Several clusters in the parietal cortex, mostly located around the intra-parietal sulcus (IPS), were also activated bilaterally. Observing gaze shifts also activated a large region in the left frontal cortex in the precentral gyrus and middle frontal gyrus, around the junction of the inferior precentral sulcus and the inferior frontal sulcus, and a cluster in the left orbital gyrus. The left parahippocampal gyrus was also activated, as was a cluster in the right lateral fissure.

Fig. 3.

Brain activity associated with gaze shifts.

’Incorrect’ gaze shift minus ’correct’ gaze shift

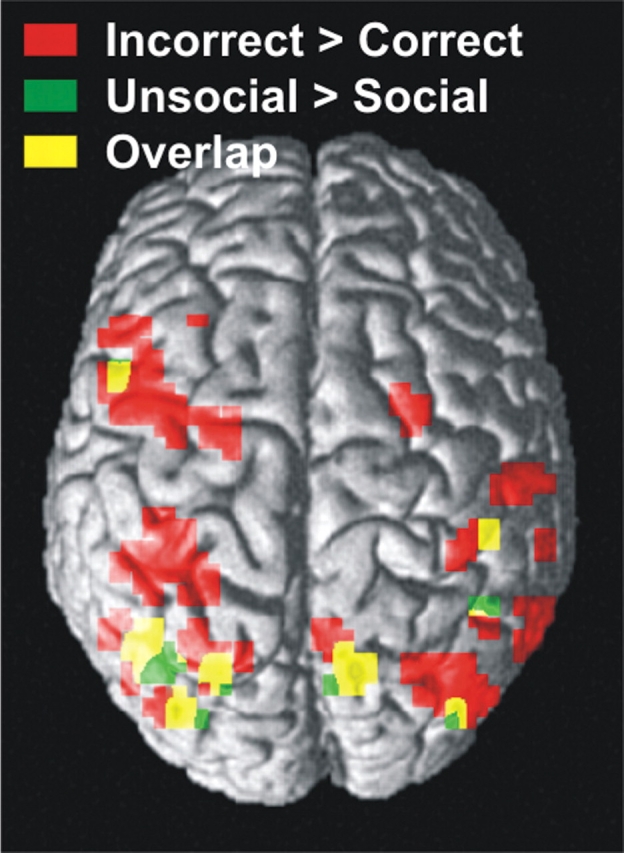

Conditions where the person made an ‘incorrect’ gaze shift, i.e. shifted their gaze but not to the target location, were compared with conditions where the person made the ‘correct’ gaze shift, i.e. shifted their gaze towards the target, at P < 0.001 uncorrected (Figure 4). This revealed areas in the parietal and frontal cortices that showed greater activation to the perception of ‘incorrect’ gaze shift than to ‘correct’ gaze shifts.

Fig. 4.

Brain activity associated with incorrect and unsocial gaze shifts.

We had hypothesised that regions activated by gaze shifts would show greater activation to ‘incorrect’ gaze shifts compared with ‘correct’ gaze shifts. Therefore we examined the contrast ‘incorrect − correct’ at a threshold of P < 0.05 uncorrected, masked by ‘gaze shift − no movement’ at a threshold of P < 0.01 uncorrected (Table 1a). This revealed the regions that respond to gaze shift that also showed a greater response to ‘incorrect’ gaze shifts. These areas included a network of regions in the parietal and frontal cortices. Parietal regions revealed were mostly located around the IPS bilaterally, and the main frontal area was a large cluster around the left precentral gyrus and the middle frontal gyrus. Areas in the occipito-temporal lobe also showed greater activation to ‘incorrect’ gaze shifts. These included an area around the anterior part of lateral occipital sulcus, the superior part of the middle occipital gyrus and parts of the posterior horizontal segment of the STS. (See Table 1a for full details of activated loci.)

Table 1.

Regions activated by incorrect gaze shifts and gaze shifts made by the unsocial face

| x | y | z | Z | P (uncorr.) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (a) Incorrect > correct (P < 0.05 uncorr.) masked by GS > NM (P = 0.01 uncorr.) | |||||

| TPS/SPG/IPS | 12 | −69 | 54 | 3.81 | 0.001 |

| TPS/SPG/IPS | −18 | −69 | 51 | 1.93 | 0.027 |

| IPS/supramarginal/angular gyrus | −33 | −45 | 39 | 3.5 | 0.001 |

| Supramarginal gyrus/IPS | 48 | −33 | 48 | 3.07 | 0.001 |

| Posterior lateral fissure | −48 | −42 | 27 | 2.9 | 0.002 |

| IPS | −24 | −69 | 33 | 3.47 | 0.001 |

| pSTSh/angular gyrus/superior MOG | 39 | −75 | 33 | 3.25 | 0.001 |

| pSTSh (and MOG) | −39 | −81 | 30 | 2.43 | 0.008 |

| PSTSh | 48 | −60 | 9 | 2.14 | 0.016 |

| STG | 63 | −39 | 18 | 2.78 | 0.003 |

| LOS | −48 | −66 | 0 | 2.68 | 0.004 |

| LOS | 60 | −63 | −6 | 2.51 | 0.006 |

| Postcentral gyrus/inferior postcentral sulcus | 51 | −21 | 36 | 2.72 | 0.003 |

| Precentral gyrus/IPCS/MFG/IFS | −39 | 0 | 39 | 2.96 | 0.002 |

| MFG/inferior frontal sulcus | −45 | 21 | 33 | 2.75 | 0.003 |

| MFG | −36 | −6 | 66 | 2.52 | 0.006 |

| Superior precentral sulcus | −45 | 3 | 54 | 2.14 | 0.016 |

| Superior frontal sulcus | 27 | −3 | 51 | 2.72 | 0.003 |

| Superior frontal sulcus | −21 | −6 | 54 | 2.36 | 0.009 |

| Superior frontal gyrus | −24 | −9 | 75 | 2.26 | 0.012 |

| Short insular gyri | −33 | 21 | 0 | 2.17 | 0.015 |

| (b) Unsocial > social (P < 0.05 uncorr.) masked by GS > NM (P = 0.01 uncorr.) | |||||

| TPS/SPG/IPS | 12 | −69 | 54 | 2.96 | 0.002 |

| IPS | −24 | −72 | 36 | 2.43 | 0.007 |

| Supramarginal gyrus | 48 | −33 | 48 | 2.4 | 0.008 |

| Angular gyrus | −36 | −81 | 33 | 1.95 | 0.026 |

| pSTSh | −42 | −69 | 15 | 1.97 | 0.025 |

| Sulcus lunatus/MOG/pSTSh | −36 | −81 | 18 | 2.69 | 0.004 |

| MOG (between pSTSh and LOS) | 39 | −81 | 24 | 2.31 | 0.01 |

| Inferior MOG/LOS | −42 | −69 | −3 | 2.91 | 0.002 |

| LOS | 48 | −54 | −3 | 2.57 | 0.005 |

| Inferior precentral sulcus | −54 | 9 | 27 | 2.55 | 0.005 |

| Anterior thalamic nucleus | −9 | −3 | 6 | 2.32 | 0.01 |

| (c) Unsocial > social (P < 0.05 uncorr.) masked by incorrect > correct (P = 0.01 uncorr.) | |||||

| TPS/SPG/IPS | 12 | −69 | 54 | 2.96 | 0.002 |

| IPS | −24 | −72 | 36 | 2.43 | 0.007 |

| Supramarginal gyrus | 51 | −33 | 48 | 2.45 | 0.007 |

| MFG | 45 | 15 | 45 | 2.63 | 0.004 |

| Inferior MFG | 48 | 33 | 30 | 2.2 | 0.014 |

| IFS | −42 | 21 | 27 | 2.05 | 0.02 |

| LOS | −45 | −66 | −3 | 2.11 | 0.017 |

GS, gaze shift; NM, no movement; MOG, middle occipital gyrus; LOS, lateral occipital sulcus; MTG, middle temporal gyrus; STG, superior temporal gyrus; pSTSh, horizontal segment of posterior superior temporal sulcus; IPS, intra-parietal sulcus; SPG, superior parietal gyrus; TPS, traverse parietal sulcus; MFG, middle frontal gyrus; SFG, superior frontal gyrus; IFS, inferior frontal sulcus; IPCS, inferior precentral sulcus.

Gaze shifts made by the ’unsocial’ face minus gaze shifts made by the ‘social’ face

Conditions where the gaze shift was made by the ‘social’ face were compared with conditions where the gaze shift was made by the ‘unsocial’ face (Figure 4). The contrast ‘unsocial − social’ (P < 0.05 uncorrected), masked by ‘gaze shift − no eye movement’ (P < 0.01 uncorrected), revealed regions activated by gaze shifts that showed greater activation to gaze shifts made by the ‘unsocial’ face than to gaze shifts made by the ‘social’ face (Table 1b). These areas included the several clusters in the superior parietal cortex bilaterally, and the left posterior horizontal STS. The lateral occipital sulcus, and the middle occipital gyrus, and the left inferior precentral sulcus areas also showed this pattern of activation, as did the left anterior thalamic nucleus. (See Table 1b for full details of activated loci.)

Areas activated by ’incorrect’ gaze shifts and gaze shifts made by the ’unsocial’ face

We examined whether the regions that show a significant response to ‘incorrect’ vs ‘correct’ gaze shifts were also activated more strongly when gaze shifts were made by the ‘unsocial’ than the ‘social’ face (Figure 4). The contrast ‘unsocial − social’ (P < 0.05) masked by ‘incorrect − correct’ (P < 0.01) revealed areas in the parietal, occipital and frontal cortices that show greater activation to ‘incorrect’ vs ‘correct’ gaze shifts, that also show a greater response to gaze shifts made by the ‘unsocial’ compared with the ‘social’ face. The parietal areas showing this pattern of activation included the right superior parietal gyrus, the right junction of the traverse- and intra-parietal sulci, the right supramarginal gyrus and the left IPS. In the occipital lobe, the region around the left lateral occipital sulcus was revealed by this contrast. In the frontal cortex, the areas showing this pattern of activation included the right middle frontal gyrus and the left inferior frontal sulcus. (See Table 1c for full details of activated loci.)

’Correct’ gaze shifts minus ’incorrect’ gaze shifts

The contrast of ‘correct’ and ‘incorrect’ gaze shifts (P < 0.001 uncorrected) revealed regions that showed greater activation to ‘correct’ gaze shifts than ‘incorrect’ gaze shifts, largely in the medial frontal cortex. These areas include the cingulate gyrus bilaterally, the medial superior frontal gyrus bilaterally, the left posterior orbital gyrus, the right fronto-polar gyrus, the left medial orbital gyrus and olfactory sulcus, and the gyrus rectus bilaterally. The left middle temporal gyrus and the right fusiform gyrus also showed greater activation for ‘correct’ compared with ‘incorrect’ gaze shifts. (See Table 2a for full details of activated loci.)

Table 2.

Regions activated by correct gaze shifts and gaze shifts made by the social face

| x | y | z | Z | P (uncorr.) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (a) Incorrect > correct (P < 0.001 uncorr.) | |||||

| Cingulate gyrus | 9 | 30 | −12 | 4.17 | 0.001 |

| Cingulate gyrus | −6 | 33 | −9 | 3.59 | 0.001 |

| Medial superior frontal gyrus | −6 | 63 | 21 | 4.05 | 0.001 |

| Superior frontal gyrus | 15 | 48 | 21 | 3.41 | 0.001 |

| Posterior orbital gyrus | −30 | 36 | −12 | 3.7 | 0.001 |

| Medial orbital gyrus/olfactory sulcus | −12 | 45 | −15 | 3.49 | 0.001 |

| Frontopolar gyri | 3 | 60 | 0 | 3.49 | 0.001 |

| Gyrus rectus | −3 | 42 | −21 | 3.42 | 0.001 |

| Circular insular sulcus | −33 | −15 | 27 | 3.31 | 0.001 |

| MTG | −66 | −24 | −6 | 4.34 | 0.001 |

| Middle occipital gyrus | 42 | −87 | 0 | 3.7 | 0.001 |

| Fusiform gyrus | 36 | −69 | −12 | 3.34 | 0.001 |

| Fornix | 6 | −21 | 18 | 3.54 | 0.001 |

| Splenium | −9 | −33 | 15 | 3.8 | 0.001 |

| (b) Social > unsocial (P < 0.05 uncorr.) masked by GS > NM (P = 0.01 uncorr.) | |||||

| Calcarine sulcus | −18 | −63 | 3 | 3.74 | 0.001 |

| Parahippocampal gyrus/hippocampus | 30 | −36 | −3 | 2.8 | 0.003 |

| Lateral orbital gyrus | −39 | 42 | −15 | 2.67 | 0.004 |

| Lateral orbital gyrus/orbital sulcus | 33 | 39 | −9 | 2.17 | 0.015 |

| MTG | −57 | −42 | −6 | 2.63 | 0.004 |

| MTG | 51 | −42 | 0 | 2.36 | 0.009 |

| MOG | −48 | −81 | 3 | 2.37 | 0.009 |

| MOG | 48 | −75 | 0 | 1.99 | 0.023 |

| Inferior MOG | −48 | −81 | −6 | 2.22 | 0.013 |

| LOS/inferior MOG | 48 | −72 | −9 | 2.41 | 0.008 |

| LOS | 39 | −69 | 6 | 2.4 | 0.008 |

| Superior frontal gyrus | −12 | −9 | 78 | 2.28 | 0.011 |

| Superior frontal gyrus | 15 | −24 | 78 | 2.27 | 0.012 |

| Superior precentral sulcus | −45 | 12 | 45 | 2.21 | 0.014 |

| Superior temporal gyrus/next to STS | 66 | −33 | 6 | 1.92 | 0.027 |

| Angular gyrus between pSTSh and IPS | 33 | −69 | 27 | 1.75 | 0.04 |

| (c) Social > unsocial (P < 0.05 uncorr.) masked by correct > incorrect (P = 0.01 uncorr.) | |||||

| Medial precuneus/cingulate gyrus | 0 | −51 | 30 | 2.97 | 0.001 |

| Medial precuneus | 3 | −60 | 18 | 2.21 | 0.013 |

| Supraorbital sulcus/SFG/cingulate sulcus | −3 | 48 | −3 | 2.96 | 0.002 |

| SFG | 9 | 54 | 24 | 2.75 | 0.003 |

| SFG/frontopolar gyri | −6 | 63 | 9 | 2.29 | 0.011 |

| SFG | −12 | 39 | 45 | 2.27 | 0.012 |

| Gyrus rectus | 0 | 30 | −30 | 2.39 | 0.009 |

| Gyrus rectus | 0 | 48 | −24 | 2.09 | 0.018 |

| H-shaped orbital sulcus | −27 | 33 | −9 | 2.3 | 0.011 |

| Inferior temporal gyrus/sulcus | 45 | 0 | −33 | 2.58 | 0.005 |

| MTG | −66 | −21 | −9 | 2.05 | 0.02 |

| Anterior MTG | −60 | −3 | −18 | 2.16 | 0.015 |

| Lingual gyrus | −3 | −84 | −3 | 2.19 | 0.014 |

| Intra/traverse occipital sulcus | −27 | −87 | 3 | 1.94 | 0.026 |

GS, gaze shift; NM, no movement.

’Social’ gaze shifts minus ’unsocial’ gaze shifts

The contrast ‘social − unsocial’ (P < 0.05), masked by ‘gaze shift − no eye movement’ (P < 0.05), revealed regions that are activated by gaze shifts that show a greater response to gaze shifts made by the ‘social’ face, than to gaze shifts made by the ‘unsocial’ face, mainly in the frontal and occipital cortices. The frontal regions included the superior frontal gyrus bilaterally, the lateral orbital gyrus bilaterally and the left superior precentral sulcus, while the occipital areas included the left calcarine sulcus, the middle occipital gyrus and lateral occipital sulcus bilaterally. Parts of the temporal lobe also showed this pattern of activation including the middle temporal gyrus bilaterally, and a cluster in right superior temporal gyrus/sulcus. The right hippocampus/parahippocampal gyrus also showed greater bilateral activation to gaze shifts made by the ‘social’ face. The only parietal region showing this pattern of activation was a cluster in the angular gyrus. (See Table 2b for full details of activated loci.)

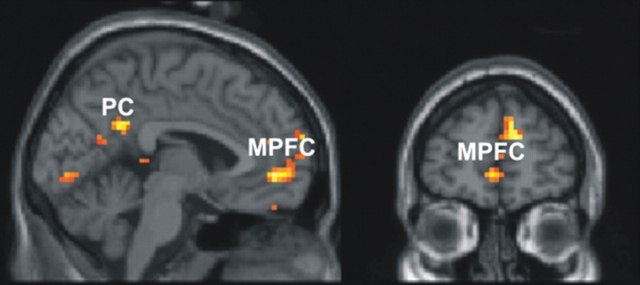

Areas activated by ‘correct’ gaze shifts and gaze shifts made by the ‘social’ face

We examined whether the regions that showed a greater response to the ‘correct’ than to ‘incorrect’ gaze shifts were also activated more strongly when gaze shifts were made by the ‘social’ than the ‘unsocial’ face (Figure 5). The contrast ‘social − unsocial’ (P < 0.05) masked by ‘correct − incorrect’ (P < 0.01) revealed areas that showed this pattern of activation. Several clusters in the MPFC showed this pattern of activation. (See Table 2c for full details of activated loci.) The medial precuneus, close to the posterior cingulate gyrus and parieto-occipital fissure also showed this pattern of activation, as did two clusters in the left middle temporal gyrus, a cluster in the traverse-occipital sulcus and a cluster in the right inferior temporal gyrus/sulcus.

Fig. 5.

Brain activity associated with correct and social gaze shifts.

Interactions

We hypothesised that the effects of goal directedness (i.e. ‘correct’ vs ‘incorrect’ gaze shifts) on the response to gaze shifts might be greater for gaze shifts made by the ‘social’ face than for those made by the ‘unsocial’ face due to the greater salience of the social face. Therefore, we looked for areas showing an interaction between the direction of the gaze shift and the face making the gaze shift within the regions showing an effect of the goal directedness of the gaze shift, such that this effect was greater for the social face.

Areas showing a greater effect of ’incorrect − correct’ for social faces

Areas showing a greater increase in response to ‘incorrect’ compared with ‘correct’ gaze shifts for ‘social’ than for ‘unsocial’ faces were revealed by masking the interaction contrast ‘(SI − SC)–(UI − UC)’ (P < 0.05 uncorrected) with ‘incorrect − correct’ (P < 0.01 uncorrected). A few small clusters showing this pattern of activation were found located in the right superior parietal gyrus where the intra- and traverse-parietal sulci meet, the supramarginal gyrus bilaterally, the right inferior frontal sulcus and the right precentral gyrus, all of which are part of the fronto-parietal attentional network.

Areas showing a greater effect of ’correct − incorrect’ for social faces

Areas showing a greater increase in response to ‘correct’ compared with ‘incorrect’ gaze shifts for ‘social’ than for ‘unsocial’ faces were revealed by masking the interaction contrast ‘(SC − SI)–(UC − UI)’ (P < 0.05) with ‘correct − incorrect’ (P < 0.01). One region located around the right middle frontal gyrus and superior frontal sulcus showed this pattern of activation.

Eye movement data analysis

There were no significant differences between experimental conditions on length of scan path, mean distance between the eye position at each time point and the average eye position. Subject's therefore fixated equally well in all conditions. There was no effect of target location, of the location of the ‘social’ face, nor of the position of the face making the gaze shift on average eye position. There was also no effect of gaze shift end position on eye position. Differences in eye movements between conditions therefore cannot account for our results.

DISCUSSION

Behavioural experiment

As hypothesised, we found a significant effect of both the direction of the gaze shift and the sociability of face making the shift on reaction times (Figure 2). Faster reaction times in the ‘correct’ condition suggest that the appearance of the target acted as an exogenous cue that directs attention covertly towards the target location. Consequently subjects were able to detect gaze shift towards this location more quickly and accurately than gaze shifts towards another location. Faster reaction times in the ‘social’ condition suggest that subjects’ attention was covertly attracted to the ‘social’ face, thus enabling faster detection of the direction of gaze shifts made by the ‘social’ face. This supports our hypothesis that subjects would be engaged more by the ‘social’ face than the ‘unsocial’ face, and the notion that direct gaze is a strongly engaging social stimulus (Von Grunau and Anston, 1995).

Functional imaging experiment

Observation of gaze shifts activated large regions of the temporo-occipital cortex, from the posterior horizontal segment of the STS to the inferior occipital sulcus, plus several bilateral clusters in the parietal cortex, mostly located around the IPS (see ‘Results’ and Figure 3). Observing gaze shifts also activated a large region in the left frontal cortex in the precentral gyrus and middle frontal gyrus, around the junction of the inferior precentral sulcus and the inferior frontal sulcus and a cluster in the left orbital gyrus. Thus, the regions activated by gaze shift in our study included the parieto-frontal network of regions that is activated by shifts of spatial attention (Nobre et al., 1997; Corbetta et al., 1998; Kato et al., 2001; Grosbras et al., 2005) and by making eye movements (Grosbras et al., 2005). The posterior STS was also activated by gaze perception in our study. Activation of these regions by gaze shifts is consistent with the results of several other studies of gaze perception including a meta analysis of eight other studies (Puce et al., 1998; Wicker et al., 1998; Hoffman and Haxby, 2000; Hooker et al., 2003; Pelphrey et al., 2003; Pelphrey et al., 2004b; Grosbras et al., 2005). Thus, our findings are consistent with the notion that gaze perception involves the face responsive region in the STS and the spatial attention network in the parietal and frontal cortices (Haxby et al., 2002).

Activation of the occipito-temporal lobe, including the middle temporal gyrus, is most likely a simple response to the motion (of the eyes) in the gaze-shift condition, as our baseline lacked any such motion. This region of activation is consistent with the location of area V5/MT, which responds to visual motion (Zeki et al., 1991).

We sought to examine whether the neural response to gaze shifts was modulated by two factors: the social context of the gaze shift (i.e. whether it was made by the socially engaging face or by the ‘unsocial’ face) and the goal directedness of the gaze shift (i.e. whether it was towards the target or not). We identified two different networks that were modulated by these factors in different ways: first, a parieto-frontal network involved in gaze perception, eye movements and shifts of attention described above; second, a network consisting of a set of medial prefrontal regions and a region in the posterior parietal/cingulate cortex. We were also specifically interested in examining modulation of gaze-perception-related activity in the STS, as the STS has already been shown to respond to the perceived intentionality of actions (Pelphrey et al., 2004a), and to have a greater response to gaze shifts when these are not made towards a visible target (Pelphrey et al., 2003).

Parieto-frontal attention network

Activity in a network of parietal and frontal regions, mainly located around the IPS and the precentral gyrus and sulcus, was greater in response to ‘incorrect’ gaze shifts than to gaze shifts that correctly acquired the target (‘correct’ gaze shifts) (P < 0.05 uncorrected masked by ‘gaze shift − no eye movement’ at P < 0.01). This is consistent with Pelphrey et al. (2003) where a greater response was found in the IPS to ‘incorrect’ vs ‘correct’ gaze shifts. A similar network of fronto-parietal regions also showed greater activation for gaze shifts made by the unsocial compared with the ‘social’ face (P < 0.05 uncorrected masked by ‘gaze shift − no eye movement’ at P < 0.01). Many studies have shown that this fronto-parietal network is involved in shifting spatial attention (Nobre et al., 1997; Corbetta et al., 1998; Kato et al., 2001; Grosbras et al., 2005) (Figure 3).

It therefore appears that the spatial attention network showed a greater response to ‘incorrect’ gaze shifts and greater activation to gaze shifts when they were made by the ‘unsocial’ face (though to a lesser extent than for ‘incorrect’ gaze shifts) (Figure 4). The difference in activation seen in this attentional network between the different conditions can simply be accounted for by the number of shifts of attention that occur in each condition.

In both ‘correct’ and ‘incorrect’ conditions, the subject's covert attention was exogenously shifted to the target location by the appearance of the target (see behavioural results). Gaze automatically induces reflexive shifts in spatial attention in the direction of gaze, thus the gaze shift that follows the appearance of the target will automatically shift the subject's attention in the direction of gaze shift (Driver et al., 1999; Langton and Bruce, 1999). In the ‘correct’ condition, the gaze shift directs the subject's attention towards the target location, but ‘incorrect’ gaze shifts direct attention away from the target. Thus, the ‘incorrect’ condition involves a second reallocation of attention, which could account for the increased activity seen in the spatial attention network.

Some parts of the parieto-frontal attentional network also showed an interaction between the effects of gaze-shift direction and the face making the gaze shift, such that the increase in activity seen during ‘incorrect’ compared with ‘correct’ gaze shifts is greater when the gaze shifts are made by the ‘social’ face. The social face is an extremely salient stimulus, thus it is likely that gaze shifts made by the social face attract the subject's attention more strongly that gaze shifts made by the unsocial face, leading to a stronger reallocation of attention from the target location in the direction of the gaze shift, in the social condition, and thus a greater increase in activation in these attentional areas.

The increased activation to gaze shifts made by the ‘unsocial’ face compared with the ‘social’ face, that we observed, may also be accounted for by a difference in the number of shifts of attention occurring in the two conditions. The direct gaze of the ‘social’ face is a very salient stimulus and attracts attention (Von Grunau and Anston, 1995), regardless of which face makes the gaze shift (as demonstrated by our behavioural data). The subject's attention is then attracted by the gaze shift. In the ‘unsocial’ condition, this involves a shift of attention from the ‘social’ to the ‘unsocial’ face, but when the ‘social’ face makes the gaze shift, this additional attentional shift does not occur as attention is already on the ‘social’ face. Reallocation of attention from the ‘social’ to the ‘unsocial’ face could account for the increased activity seen in areas involved in spatial attention in response to gaze shifts, made by the ‘unsocial’ face.

Medial prefrontal cortex

It has been proposed that the MPFC is involved in representing shared attention and goals, and more specifically ‘triadic relations between Me, You, and This’, i.e. the subject, a second person and an object (Saxe, 2006). The only relevant neuroimaging study to date found that joint attention is associated with activity in the MPFC (Williams et al., 2005). Activation of a medial prefrontal network by ‘correct’ (compared with ‘incorrect’) gaze shifts in our experiment is consistent with this region's involvement in joint attention, because during the ‘correct’ conditions the attention of both the subject and the face stimulus were directed towards the target, so the subject experiences joint attention with the face. This joint attention is covert as the subjects maintained fixation and did not move their eyes towards the target. In contrast, in the ‘incorrect’ condition the subject's attention was attracted to the target but then the face stimuli shifted their eyes, and by implication their attention, to a different location. Thus, in this situation, the subject did not experience joint attention, so activity in the MPFC might not be expected.

Similar regions were activated by ‘correct’, compared with ‘incorrect’, gaze shifts and by gaze shifts made by the ‘social’ vs the ‘unsocial’ face. These included areas in the MPFC and also a cluster in the medial precuneus (Figure 5). Like the MPFC, the medial precuneus was also activated by joint attention in the experiment described above (Williams et al., 2005). Thus it appears that the network of areas involved in joint attention were activated when the face made ‘correct’ gaze shifts and also when gaze shifts were made by the ‘social’ face.

Such modulation of prefrontal activity by the sociability of the face is consistent with a previous experiment where virtual characters on a screen looked at the subject or at an imaginary other, and made socially relevant, for example a smile, or arbitrary facial movements (Schilbach et al., 2006). The facial movements made by the character looking at the subject, the equivalent to the ‘social’ face in our experiment, elicited greater activation in the anterior dorsal MPFC than movements made by the face with averted gaze, equivalent to our ‘unsocial’ face. Thus activation in the MPFC appears to reflect the feeling of personal involvement.

Direct gaze is a very salient and engaging social stimulus (Von Grunau and Anston, 1995) and it indicates that you are the object of another's attention. Direct or mutual gaze is a case of joint attention involving just the two individuals (dyadic attention), and often signals the intention to communicate, leading to triadic joint attention (Saxe, 2006). Thus, perhaps the direct gaze of the ‘social’ face in our experiment makes the gaze shifts made by that face feel like intentional communicative gestures (Kampe et al., 2003), enhancing the feeling of joint attention, whereas when the ‘unsocial’ face makes a gaze shift, there is no apparent intention to communicate. Perhaps the greater activity in the MPFC for gaze shifts made by the ‘social’ face reflects this perception of the gaze shift as an intentional communicative gesture.

Superior temporal sulcus

Bilateral regions of the posterior horizontal segment of the STS and adjacent middle occipital gyrus showed a greater response to ‘incorrect’ compared with ‘correct’ gaze shifts (P < 0.05 uncorrected masked by ‘gaze shift − no eye movement’ at P < 0.01). This is consistent with the results of Pelphrey et al. (2003), who found that activity in the STS lasted significantly longer for gaze shifts towards empty locations in space than for gaze shifts towards a target. The posterior STS is involved in predicting the actions of others (Ramnani and Miall, 2004) and Pelphrey and colleagues propose that prolonged activation of the STS observed for ‘incorrect’ gaze shifts reflects violation of the observer's prediction (Pelphrey et al., 2003). The observer predicts that the face will look towards the target when it appears, and when this occurs, their expectations are met. However, when the face shifts its gaze to another location, the observer's prediction is violated, leading to increased STS activity, perhaps due to reformulation of the observer's expectations about the other's behaviour, or due to the prediction of second gaze shift from the empty location to the target (Pelphrey et al., 2003). This effect appears to be less strong in our experiment than for Pelphrey and colleagues (2003), perhaps because the maximum distance between the target and the end point of an ‘incorrect’ gaze shift was 90° in our study, whereas in Pelphrey's experiment the target and the end point of an ‘incorrect’ gaze shift could be as much as 180° apart. A greater discrepancy between the target and the gaze shift could cause even greater activation in the STS.

The left posterior horizontal segment of the STS and the bilateral middle occipital gyrus, just below the STS, also showed greater activation to gaze shifts made by the ‘social’ face vs the ‘unsocial’ face. As with the increased activity for ‘incorrect’ gaze shifts, this increase in activity for the ‘unsocial’ face can be explained in terms of expectation violation. Eye contact can signal the intention to communicate (Kampe et al., 2003; Saxe, 2006) and as such the observer might expect the face looking at them to indicate the presence of the target by looking at it, more than they expect the ‘unsocial’ face to do so. When the ‘social’ face makes the eye movement, this expectation is met, but when the ‘unsocial’ face makes the gaze shift, the expectation is violated leading to increased activity in the STS as new predictions are generated.

SUMMARY

We have demonstrated that both behavioural and neural responses to gaze shifts are modulated by the social context and the goal directedness of that gaze shift. Reaction times were significantly faster in response to ‘correct’ and ‘social’ compared with ‘incorrect’ and ‘unsocial’ gaze shifts, respectively. We found significantly greater activation in the parieto-frontal attentional network, and in some parts of the posterior STS, in response to ‘incorrect’ and ‘unsocial’ compared with ‘incorrect’ and ‘social’ gaze shifts, respectively. We suggest that this activity occurred because ‘incorrect’ and ‘unsocial’ gaze shifts are unexpected and induce additional shifts of attention. Conversely, we found greater activation in the MPFC and precuneus in response to ‘correct’ and ‘social’ compared with ‘incorrect’ and ‘unsocial’ gaze shifts, respectively. We suggest that this activity reflects the experience of joint attention elicited by ‘correct’ and ‘social’ gaze shifts. By having both the ‘social’ and the ‘unsocial’ faces on screen at all times, we were able to control for the presence of direct and averted gaze, and specifically examine the effects of social context on the response to gaze shifts. We would expect to see the same effects of social context on gaze processing if only one face was presented, on top of effects due simply to the presence of direct or averted gaze; but this remains an empirical question for future study.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the Wellcome Trust.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

REFERENCES

- Ashburner J, Friston KJ. Nonlinear spatial normalization using basis functions. Human Brain Mapping. 1999;7:254–66. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0193(1999)7:4<254::AID-HBM4>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron-Cohen S. Mindblindness: an Essay on Autism and Theory of Mind. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Corbetta M, Akbudak E, Conturo TE, et al. A common network of functional areas for attention and eye movements. Neuron. 1998;21:761–73. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80593-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driver J, Davis G, Ricciardelli P, Kidd P, Maxwell E, Baron-Cohen S. Gaze perception triggers reflexive visuospatial orienting. Visual Cognition. 1999;6:509–40. [Google Scholar]

- Friston KJ, Ashburner J, Frith CD, Heather JD, Frackowiak RS. Spatial registration and normalisation of images. Human Brain Mapping. 1995;3:165–89. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson JJ, Pick A. Perception of another person's looking behavior. The American Journal of Psychology. 1963;76:386–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grosbras MH, Laird AR, Paus T. Cortical regions involved in eye movements, shifts of attention, and gaze perception. Human Brain Mapping. 2005;25:140–54. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haxby JV, Hoffman EA, Gobbini MI. Human neural systems for face recognition and social communication. Biological Psychiatry. 2002;51:59–67. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01330-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman EA, Haxby JV. Distinct representations of eye gaze and identity in the distributed human neural system for face perception. Nature Neuroscience. 2000;3:80–4. doi: 10.1038/71152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hood BM, Willen JD, Driver J. Adult's eyes trigger shifts of visual attention in human infants. Psychological Science. 1998;9:131–4. [Google Scholar]

- Hooker CI, Paller KA, Gitelman DR, Parrish TB, Mesulam MM, Reber PJ. Brain networks for analyzing eye gaze. Brain Research Cognitive Brain Research. 2003;17:406–18. doi: 10.1016/s0926-6410(03)00143-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kampe KK, Frith CD, Frith U. “Hey John”: signals conveying communicative intention toward the self activate brain regions associated with “mentalizing,” regardless of modality. Journal of Neuroscience. 2003;23:5258–63. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-12-05258.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato C, Matsuo K, Matsuzawa M, Moriya T, Glover GH, Nakai T. Activation during endogenous orienting of visual attention using symbolic pointers in the human parietal and frontal cortices: a functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Neuroscience Letters. 2001;314:5–8. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(01)02207-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langton SR, Bruce V. Reflexive visual orienting in response to the social attention of others. Visual Cognition. 1999;6:541–67. [Google Scholar]

- Mazziotta JC, Toga AW, Evans A, Fox P, Lancaster J. A probabilistic atlas of the human brain: theory and rationale for its development. The International Consortium for Brain Mapping (ICBM) Neuroimage. 1995;2:89–101. doi: 10.1006/nimg.1995.1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nobre AC, Sebestyen GN, Gitelman DR, Mesulam MM, Frackowiak RS, Frith CD. Functional localization of the system for visuospatial attention using positron emission tomography. Brain. 1997;120(Pt 3):515–33. doi: 10.1093/brain/120.3.515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelphrey KA, Morris JP, McCarthy G. Grasping the intentions of others: the perceived intentionality of an action influences activity in the superior temporal sulcus during social perception. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2004a;16:1706–16. doi: 10.1162/0898929042947900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelphrey KA, Singerman JD, Allison T, McCarthy G. Brain activation evoked by perception of gaze shifts: the influence of context. Neuropsychologia. 2003;41:156–70. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3932(02)00146-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelphrey KA, Viola RJ, McCarthy G. When strangers pass: processing of mutual and averted social gaze in the superior temporal sulcus. Psychological Science. 2004b;15:598–603. doi: 10.1111/j.0956-7976.2004.00726.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puce A, Allison T, Bentin S, Gore JC, McCarthy G. Temporal cortex activation in humans viewing eye and mouth movements. Journal of Neuroscience. 1998;18:2188–99. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-06-02188.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramnani N, Miall RC. A system in the human brain for predicting the actions of others. Nature Neuroscience. 2004;7:85–90. doi: 10.1038/nn1168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizzolatti G, Riggio L, Dascola I, Umilta C. Reorienting attention across the horizontal and vertical meridians: evidence in favor of a premotor theory of attention. Neuropsychologia. 1987;25:31–40. doi: 10.1016/0028-3932(87)90041-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxe R. Uniquely human social cognition. Current Opinion in Neurobiology. 2006;16:235–9. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2006.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schilbach L, Wohlschlaeger AM, Kraemer NC, et al. Being with virtual others: neural correlates of social interaction. Neuropsychologia. 2006;44:718–30. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2005.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Von Grunau M, Anston C. The detection of gaze direction: a stare-in-the-crowd effect. Perception. 1995;24:1297–313. doi: 10.1068/p241297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wicker B, Michel F, Henaff MA, Decety J. Brain regions involved in the perception of gaze: a PET study. Neuroimage. 1998;8:221–7. doi: 10.1006/nimg.1998.0357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams JH, Waiter GD, Perra O, Perrett DI, Whiten A. An fMRI study of joint attention experience. Neuroimage. 2005;25:133–40. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.10.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeki S, Watson JD, Lueck CJ, Friston KJ, Kennard C, Frackowiak RS. A direct demonstration of functional specialization in human visual cortex. The Journal of Neuroscience. 1991;11:641–9. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-03-00641.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]