Abstract

Background

Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) encodes genetically diverse K1 alleles which have unique geographic distributions. Little is known about K1 genetic diversity in Zimbabwe where acquired immunodeficiecney syndrome-associated KS (AIDS-KS) is epidemic.

Objective

Evaluate K1 diversity in Zimbabwe and compare Zimbabwean K1 diversity to other areas in Africa.

Study Design

K1 nucleotide sequence was determined for AIDS-KS cases in Zimbabwe. K1 references sequences were obtained from Genbank.

Results

Among 65 Zimbabwean AIDS-KS cases, 26 (40%) were K1 subtype A and 39 (60%) were subtype B. Zimbabwean subtype A sequences grouped only with African intratype A5 variants. Zimbabwean subtype B sequences grouped with multiple intratype African variants: 26 B1 (26%), four B3 (6%) and nine highly divergent B4 (14%). Zimbabwean subtype B had a lower synonymous to nonsynonymous mutation ratio (median 0.59 versus 0.66; P=0.008) and greater distance to the most recent common ancestor (median 0.03 versus 0.009; P<0.001) compared to subtype A. Within the B subgroup, the distribution of intratype B variants differed in Zimbabwe and Uganda (P=0.004).

Conclusions

Greater positive selection and genetic diversity in K1 subtype B compared to subtype A5 exist in Zimbabwe. However, there were no significant associations between K1 subtype and the clinical or demographic characteristics of AIDS-KS cases.

Keywords: Kaposi’s sarcoma, KSHV, K1, human herpesvirus 8, phylogenetics

INTRODUCTION

The K1 gene of Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) codes a transmembrane protein that activates cell-signaling pathways (Lagunoff et al., 1999; Tomlinson and Damania, 2004) and induces expression of angiogenic and invasion factors (Wang et al., 2004). There is substantial K1 genetic diversity in circulating KSHV strains (Biggar et al., 2000; Cook et al., 1999; Meng et al., 1999; Zong et al., 1999). Among KSHV subtypes A, B, C, D and E, there is a 15–30% amino acid difference overall and a 30–60% amino acid difference within two K1 variable regions, VR1 and VR2 (Nicholas et al., 1998; Zong et al., 1999; Biggar et al., 2000). The high rate of nonsynonymous to synonymous substitution in K1 suggests that K1 is undergoing positive biological selection and could be an important virulence factor and/or target of the host immune system (Cook et al., 1999; Hayward, 1999; McGeoch and Davidson, 1999).

KS is currently the most frequent cancer in many African populations and accounts for 48% and 40% of all cancers in men in Uganda and Zimbabwe, respectively (Wabinga et al., 1993; Chokunonga et al 1999). Zimbabweans with AIDS-KS typically have advanced HIV-1 disease, KSHV viremia, high tumor burdens, and short survival (Campbell et al., 2003; Olweny et al., 2005). Much of what is known about K1 diversity in African populations comes from studies of persons with KS in East and Central Africa (Zong et al., 1999; Zong et al., 2002; Lacoste et al., 2000). Little is known about KSHV genetic diversity in Zimbabwe. The present study evaluated the hypothesis that significant K1 genetic diversity exists among persons with AIDS-KS in Zimbabwe and that the distribution of K1 genotypes in Zimbabwe is similar to other areas of Africa.

METHODS

Study population

AIDS-KS cases were recruited from the Parirenyatwa Hospital KS Clinic, Harare, Zimbabwe. The characteristics of the participants have been described previously (Campbell et al., 2003). Informed consent was obtained after the nature and possible consequences of study participation was fully explained. Only subjects born within Zimbabwe were included in the present study. Cities of birth were classified as urban (population > 10,000) or rural (population < 10,000 according to the 2002 population census (http://www.gazetteer.de). KS clinical stage was determined at study entry on the basis of clinical data by the following criteria (Krigel et al., 1983).

KSHV ORF K1 amplification and cloning

DNA from plasma and/or peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PMBCs) was available for 171 Zimbabwean AIDS-KS patients. KSHV ORF K1 was amplified from PBMC or plasma DNA by nested PCR, as described elsewhere (Zong et al., 1999). Two positive control reactions, containing 1 or 100 copies of K1 DNA were included in each PCR. PCR-amplified DNA was directly analyzed by automated nucleotide sequence analysis. For one subject, molecular clones were generated and analyzed. PCR product was not obtained from 106 subjects because of insufficient DNA.

DNA sequencing and phylogenetic analysis of KSHV ORF K1

Nucleotide sequences were obtained for VR1 and VR2 with both forward and reverse primers, manually edited with Sequencher 4.0.5 (Gene Codes), aligned with ClustalW in Bioedit 5.0 (http://www.mbio.ncsu.edu/BioEdit/bioedit.html), and translated with Bioedit 5.0. Inferred phylogenetic trees were constructed by neighbor-joining /UPGMA analysis by DNAdist or Protdist in Bioedit. Bootstrap analyses were performed by Seqboot in Phylip 3.6 (http://evolution.genetics.washington.edu/phylip.html). Bootstrap values greater than or equal to 80% were considered significant. Inferred trees were depicted with Treeview 1.5 (http://taxonomy.zoology.gla.ac.uk/rod/rod.html). Synonymous and non-synonymous rates were calculated by SNAP (http://www.hiv.lanl.gov/content/hivdb/ mainpage.html).

K1 sequences from 57 isolates, representing the three major KSHV subtypes (A, B, and C) and the countries of Uganda, Zambia, Tanzania, South Africa, Gambia, Zaire and the United States, were incorporated into phylogenetic trees as references. RKS1, RKS2, RKS3, RKS4 and RKS5 were provided by Dr. Gary S. Hayward. Other reference sequences were obtained from Genbank (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Genbank/index.html). Only K1 sequences that contained at least 90 percent of VR1-VR2 region were included.

Statistical Methods

Between group characteristics were compared with Mann-Whitney tests for continuous variables and Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables using SysStat (Systat Software, Inc., Richmond, CA) and SigmaStat (Systat Software, Inc., Richmond, CA). Analyses were not corrected for multiple comparisons.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers

New nucleotide sequences were deposited in GenBank using the National Center for Biotechnology Information (Bethesda, MD) Sequin v. 5.26 submission tool under accession numbers DQ309700 – DQ309725 (A5), DQ309726 – DQ309762 (B1), and DQ309696 – DQ309699 (B2).

RESULTS

Identification of a novel K1 subtype B4

K1 sequences from 50 Zimbabwean men and 15 Zimbabwean women with AIDS-KS were analyzed. Median age and CD4+ lymphocytes were 34 years (range, 18–66 years) and 160 mm−3 (range 2–724 mm−3), respectively. Sixty-three subjects were Shona-speaking Africans from the northeastern two thirds of Zimbabwe. Two subjects were Ndebele-speaking Africans from the southwestern portion of Zimbabwe.

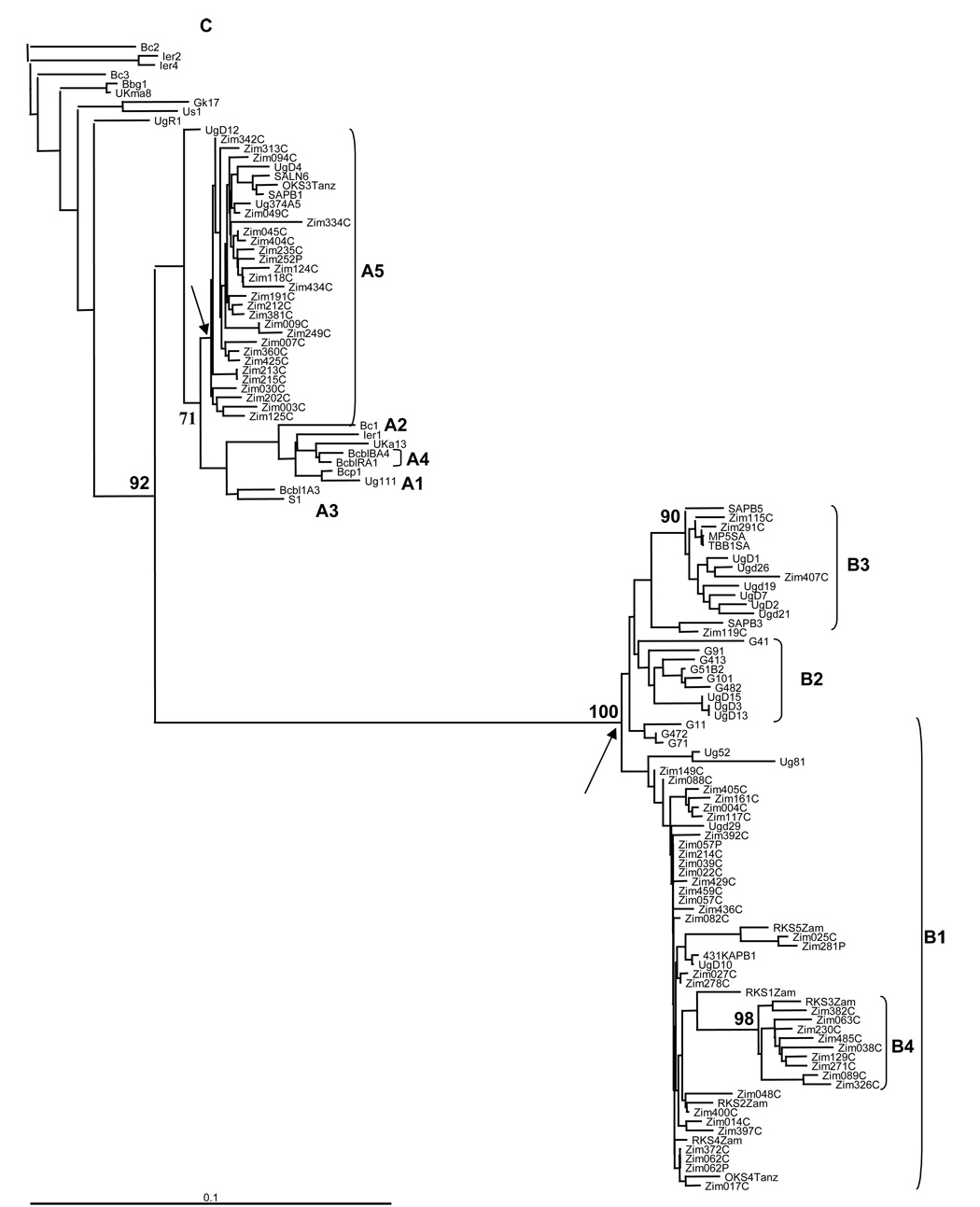

All Zimbabwean K1 nucleotide and amino acid sequences grouped with either subtype A or B reference sequences (Fig. 1 and Fig. 2) and the A and B groupings were supported by bootstrap values of 92% and 100%, respectively (Fig. 1). Twenty six subjects were infected with subtype A (40%); thirty nine were infected with B (60%). Other K1 subtypes were not detected. No evidence of intrasubject KSHV genetic heterogeneity was found by visual inspection of sequence chromatograms, analysis of K1 sequences from paired plasma and PBMC specimens or, in one case, by DNA sequence analysis of seven molecular clones from a single participant.

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic analysis of Kaposi’s sarcoma associated herpesvirus (KSHV) K1 in Zimbabwe. The inferred tree includes DNA sequences amplified from plasma or peripheral blood mononuclear cell samples from 65 Zimbabwean subjects and 60 reference sequences from previous studies. The BC-2 sequence was used as the out-group for depiction of the tree. Bootstrap values calculated from 1000 replicate trees are noted at major branch points as a percentage. Horizontal branch lengths are drawn to scale, with the bar at the bottom left corner representing 10% divergence. Letters after patient identifiers: C, peripheral blood mononuclear cell; P, plasma. Letters within reference identifiers: G, The Gambia, SA, South Africa; Tanz, Tanzinia; Ugd, Uganda; Zam, Zambia; Zim, Zimbabwe. Arrows indicate the most recent Zimbabwean common ancestor (MRCA) node for the A5 and B groups. Subgroup classification is as proposed by Kajumbula, et al., except for the designation of new B4 subgroup that was supported by a bootstrap value of 98%.

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic analysis of Kaposi’s sarcoma associated herpesvirus (KSHV) K1 subgroup A5, B1 and B2 protein sequences inferred from the DNA sequences in Figure 1. The BC-2 sequence was used as the out-group for depiction of the tree. Horizontal branch lengths are drawn to scale, with the bar at the bottom left corner representing 10% divergence. Letters after patient identifiers: C, peripheral blood mononuclear cell; P, plasma. Letters within reference identifiers: G, The Gambia; SA, South Africa; Tanz, Tanzania; Ugd, Uganda; Zam, Zambia; Zim, Zimbabwe. Subgroup classification is the same as in Figure 1.

The K1 nucleotide and amino acid sequences in the A subtypes all grouped with A5 reference sequences from other parts of Africa. The Zimbabwean A5 group was phylogenetically homogenous and no significant phylogenetic subgroupings were observed (Fig. 1 and Fig. 2). In contrast, there was phylogenetic diversity among Zimbabwean K1 sequences that grouped within the B subgroup. Thirty of 39 Zimbabwean K1 subtype B sequences grouped with multiple Ugandan, Zambian, Tanzanian, or South African reference sequences that were previously designated as belonging to the B1 or B3 subgroups.

Nine Zimbabwean B sequences did not group with B1, B2 or B3 reference sequences and instead grouped with a closely related Zambian sequence. Although the single Zambian sequence in the later group was previously designated as B1, a new grouping was supported by a bootstrap value of 98% and was therefore designated as a novel fourth group of intratype B variants (B4). Most polymorphisms among the B4 sequences were within VR1 and the adjacent downstream area from codons 100 to 150. Only one amino acid substitution was detected in VR2 of subgroup B4.

Higher nonsynonymous mutation rates in Zimbabwean KSHV subtype B

The phylogenetic groupings of K1 nucleotide and amino sequences were similar (compare Fig. 1 and Fig. 2). In-frame nucleotide deletions in the VR2 region were detected in six A and four B Zimbabwean sequences. Out of frame deletions and stop codons within K1 were not detected. Both synonymous and nonsynonymous mutations were detected throughout the VR1 (codons 52 to 92) and VR2 (codons 191 to 231) regions of K1, but were uncommon in the conserved region between VR1 and VR2 (codons 93 to 190) in the A5 subtype (Fig. 3A). In contrast, in subtype B both synonymous and nonsynonymous mutations occurred throughout K1 including the region between VR1 and VR2 that was highly conserved in A5 viruses (Fig. 3B). Nonsynonymous mutations were more common than synonymous mutations in both subtypes A5 and B. Zimbabwean subtype B had a lower dS/dN ratio compared to subtype A5 (median 0.59 versus 0.66, respectively; P = 0.008) and the lowest dS/dN ratio was in the divergent intertype B4 group (0.44; P < 0.001).

Figure 3.

Per codon nonsynonymous and synonymous mutation rates and synonymous to nonsynonymous mutation ratio (dS/dN) for the VR1-VR2 region of Zimbabwean K1 genes. (A) Zimbabwean subtype A5 K1 nucleotide sequences from Figure 1; (B) Zimbabwean subtype B K1 nucleotide sequences from Figure 1. The location of the K1 hypervariable regions (VR1 and VR2) is indicated by bars at the bottom.

Greater genetic diversity in Zimbabwean K1 subtype B

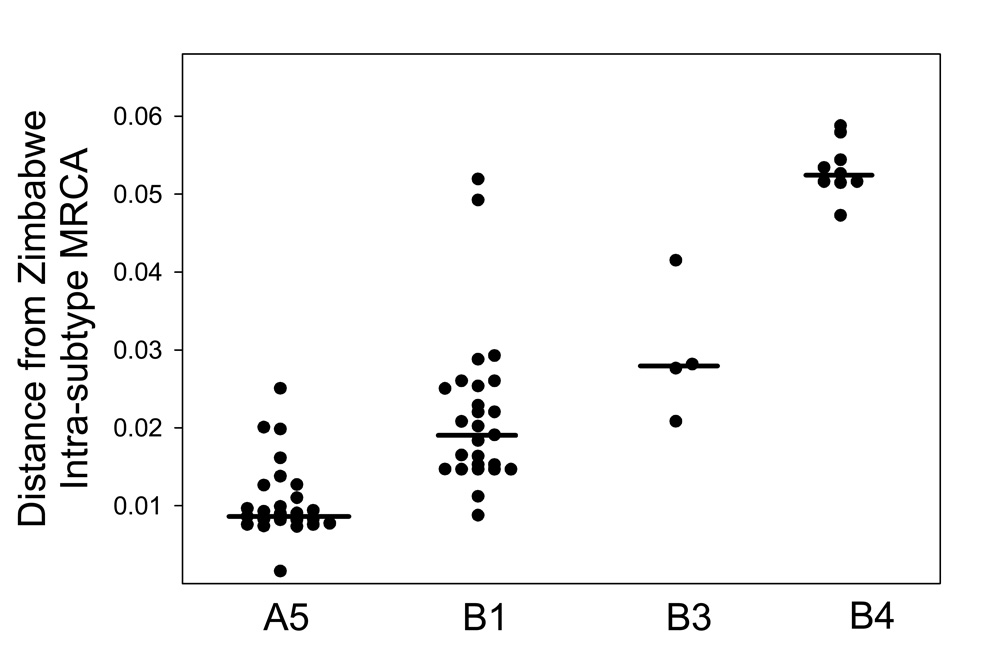

The median distance to the most recent common ancestor (MRCA) was 3.3-fold greater in Zimbabwean K1 subtype B compared to A5 (0.03 versus 0.009; Fig. 4A; P < 0.001). There was also significant intratype genetic diversity within the subtype B group; the median distance to the subtype B MRCA for subgroups B1, B3, and B4 was 0.02, 0.03, and 0.05, respectively (Fig. 4B; P < 0.001).

Figure 4.

K1 nucleotide sequence distance to the most common recent Zimbabwean ancestor (MRCA). Each point represents the nucleotide sequence difference between a Zimbabwean K1 DNA sequence and the MRCA for Zimbabwean sequences within the A and B subtypes shown by the arrows in Figure 1. Horizontal bars are the median distance for each grouping from the Zimbabwe MRCA for either the A or B subtypes.

Clinical, demographic and geographic characteristics of K1 subtype A and B infection

Age, gender and CD4+ lymphocyte count were similar for Zimbabweans with subtype A and B infection (P ≥ 0.2 for each comparison). There were trends towards decreased odds of subtype A5 infection among persons with disseminated AIDS-KS (OR = 0.48; 95% CI 0.17, 1.32; P = 0.07) and in persons born in a rural area (OR = 0.26; 95% CI 0.18, 1.38; P = 0.08). Thirty five subjects reported being born in one of the administrative districts that comprise the northern most provinces of Mashonaland East, Central and West. The other 30 participants were born in districts within the more southern provinces of Masvingo, Manicaland, Midlands and Matebeleland South. Three were no significant differences in the geographic distributions of subtype A and B in Zimbabwe.

The frequency of different K1 types variants observed in the 65 Zimbabweans in our study and in 48 Ugandan patients from previous studies (Cook et al. 1999, Kajumbula et al. 2006, Kakoola et al. 2001) were compared (Table 1). Although K1 subtypes C and F collectively represented 10% of Ugandan sequences, these subtypes were not found in Zimbabwe. The distribution of intratype B variants was different in Uganda and Zimbabwe (P = 0.004). Intratype B2 infection occurred in 4% of Ugandan cases but was not identified in Zimbabwe, and intratype B4 which occurred in 14% of Zimbabwean cases was not identified in Uganda.

Table 1.

Comparison of K1 subtype distribution in Uganda and Zimbabwe.

| Subtype A | Subtype B | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Countrya | Number | 1 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | C | F |

| Ugandab | 48 | 1 (2%) | 21 (44%) | 13 (27%) | 2 (4%) | 6 (13%) | 0 | 4 (8%) | 1 (2%) |

| Zimbabwec | 65 | 0 | 26 (40%) | 26 (40%) | 0 | 4 (6%) | 9 (14%) | 0 | 0 |

P = 0.004 for a Fisher’s exact test comparison of the number of intra-type B variants B1, B2, B3 and B4 in Uganda and Zimbabwe.

Subtype data for Uganda are from Kajumbula, et al. (32 subjects), Cook et al. (7 subjects) and Kakoola et al. (9 subjects). Since the B2 and B3 subtype categories used by Kajumbula, et al. and the present study were not used in the Cook et al. and Kakoola et al. studies, the subtype B sequences reported by Cook et al. and Kakoola et al. were incorporated into the phylogenetic tree depicted in Figure 1 to determine subtype B1, B2, B3 and B4 categorization.

Subtype categorization of Zimbabwean K1 sequences is from the phylogenetic tree depicted in Figure 1.

DISCUSSION

Our study adds to the current knowledge of worldwide KSVH molecular epidemiology by providing the first in-depth analysis of the genetic variability of K1 in Zimbabwe. In contrast to other studies of K1 epidemiology in central Africa which included multiple ethnic and cultural groups, our study population in Zimbabwe consisted of Africans with uniform racial and cultural characteristics. Despite the uniformity in our study population, we found evidence for significant evolutionary and geographical differences in the Zimbabwean A5 and B subtypes of K1. First, the B subtype had evidence of greater positive selection than the A5 subtype. In subtype B, the majority of mutations in K1 were nonsynonymous. While non-synonymous mutations in K1 subtype A5 were almost exclusively limited to the variable regions VR1 and VR2, non-synonymous mutations in subtype B occurred throughout the extracellular domain of K1, including the more conserved connecting region. Second, there was greater genetic diversity within subtype B compared to A5 and greater distance to the most recent common Zimbabwean ancestor for the B compared to A5 groupings. Lastly, there were geographic differences in the frequency of intratype B variants in central versus southern Africa. B2 which occurs in Uganda and The Gambia was not found in Zimbabwe. The novel B4 group, identified by a clustering of Zimbabwean sequences with a reference sequence from neighboring Zambia was not noted in prior studies in other parts of Africa and may be unique to southern Africa.

One hypothesis to explain the distribution of K1 subtype A5 in Africa is that a prototype A5 gene was introduced into African populations through a “very rapid and recent aggressive spread” augmented by a selective advantage of the A5 allele (Hayward and Zong, 2006). Indeed, the prevalence of subtype A5 in Zimbabwe (45%) is remarkably similar to that observed in smaller studies of other ethnic groups in diverse geographic areas in Africa: A5 was identified in 53% of 31 KS patients in Uganda (Kajumbula et al. 2006) and 34% of 32 KS patients in West and Central African countries (Lacoste et al. 2000). Zimbabwean A5 sequences in our study were closely related to each other and to reference sequences from distant areas of Africa with little evidence of genetic diversity.

We conclude that greater positive selection and genetic diversity in K1 subtype B compared to A5 in Zimbabwe support previous proposals that A5 was recently introduced into Africa and subtype B is a more ancient African K1 allele (Cook et al., 1999; Zong, 1999). However, our study does not confirm a previous report that subtype A is associated with more oadvanced KS disease and higher CD4+ lymphocyte counts (Boralevi et al., 1998).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was facilitated by the infrastructure and resources provided by the Colorado Center for AIDS Research Grant P30 AI054907. Tiffany White was supported by National Institutes of Health grants 5T32AI07537-04 and AI-07447. The DNA samples were sequenced by the University of Colorado Cancer Center DNA Sequencing and Analysis Core (http://loki.uchsc.edu), which is supported by the NIH/NCI Cancer Core Support Grant (P30 CA046934). No authors have a commercial or other association that would pose a conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- Biggar RJ, Whitby D, Marshall V, Linhares AC, Black F. Human herpesvirus 8 in Brazilian Amerindians: hyperendemic population with a new subtype. J Infect Dis. 2000;181:1562–1568. doi: 10.1086/315456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boralevi F, Masquelier B, Denayrolles M, Dupon M, Pellegrin J–L, Ragnaud J–M, Fleury HJA. Study of human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8) variants from Kaposi's sarcoma in France: Is HHV-8 subtype A responsible for more aggressive tumors? J Infect Dis. 1998;178:1546–1547. doi: 10.1086/314471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell TB, Borok M, White IE, Gudza I, Ndemera B, Taziwa A, Weinberg A, Gwanzura L. Relationship of Kaposi sarcoma (KS)-associated herpesvirus viremia and KS disease in Zimbabwe. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36:1144–1151. doi: 10.1086/374599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chokunonga E, Levy IM, Bassett MT, Borok MZ, Manuchaza BG, Chirenje MZ, Parkin DM. AIDS and cancer in Africa: The evolving epidemic in Zimbabwe. AIDS. 1999;13:2583–2588. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199912240-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook PM, Whitby D, Calabro ML, Luppi M, Kakoola DN, Hjalgrim H, Ariyoshi K, Ensoli B, Davidson AJ, Schultz TF the International Collaborative Group. Variability and evolution of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpes-virus in Europe and Africa. AIDS. 1999;13:1165–1176. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199907090-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayward GS. KSHV strains: The origins and global spread of the virus. Semin Cancer Biol. 1999;9:187–199. doi: 10.1006/scbi.1998.0116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayward GS, Zong J-C. Modern evolutionary history of the human KSHV genome. Cur Topics Microbiol Immunol. 2007;312:1–42. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-34344-8_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kajumbula H, Wallace RG, Zong JC, Hokello J, Sussman N, Simms S, Rockwell RF, Pozos R, Hayward GS, Boto W. Ugandan Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus phylogeny: Evidence for cross-ethnic transmission of viral subtypes. Intervirol. 2006;49:133–143. doi: 10.1159/000089374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakoola DN, Sheldon J, Byabazaire N, Bowden RJ, Katongole-Mbiddle E, Schultz TF, Davison AJ. Recombination in human herpesvirus-8 strains from Uganda and evolution of the K15 gene. J Gen Virol. 2001;82:2393–2404. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-82-10-2393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacoste V, Judde JG, Briere J, Tulliez M, Garin B, Kassa-Kelembho E, Morvan J, Couppie P, Clyti E, Forteza Vila J, Rio B, Delmer A, Mauchlere P, Gessain A. Molecular epidemiology of human herpesvirus 8 in Africa: both B and A5 K1 genotypes, as well as the M and P genotypes of K14.1/K15 loci, are frequent and widespread. Virology. 2000;278:60–74. doi: 10.1006/viro.2000.0629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagunoff M, Majeti R, Weiss A, Ganem D. Deregulated signal transduction by the K1 gene product of Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:5704–5709. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.10.5704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGeoch DJ, Davidson AJ. The descent of human herpesvirus 8. Semin Cancer Biol. 1998;9:201–209. doi: 10.1006/scbi.1999.0093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nei M, Gojobori T. Simple methods for estimating the numbers of synonymous and nonsynonymous nucleotide substitutions. Mol Biol Evol. 1986;3:418–426. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholas J, Zong JC, Alcendor DJ, Ciufo DM, Poole LJ, Sarisky RT, Chiou C–J, Zhang X, Wan X, Guo H-G, Reitz MS, Hayward GS. Novel organizational features, captured cellular genes, and strain variability within the genome of KSHV/HHV8. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 1998;23:79–88. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jncimonographs.a024179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olweny CL, Borok M, Gudza I, Clinch J, Cheang M, Kiire CF, Levy L, Otim-Oyet D, Nyamasve J, Schipper H. Treatment of AIDS-associated Kaposi’s sarcoma in Zimbabwe: results of a randomized quality of life focused clinical trial. Int J Cancer. 2005;113:632–639. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomlinson CC, Damania B. The K1 protein of Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus activates the Akt signaling pathway. J Virol. 2004;78:1918–1927. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.4.1918-1927.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wabinga HR, Parkin DM, Wabire-Mangen F, Mugerwa JW. Cancer in Kampala, Uganda, in 1989–91: Changes in incidence in the era of AIDS. Int J Cancer. 1993;54:26–36. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910540106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Wakisaka N, Tomlinson CC, DeWire SM, Krall S, Pagano JS, Damania B. The Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV/HHV-8) K1 protein induces expression of angiogenic and invasion factors. Cancer Res. 2004;64:2774–2781. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-3653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zong JC, Ciufo DM, Alcendor DJ, Wan X, Nicholas J, Browning PJ, Rady PL, Tyring SK, Orenstein JM, Rabkin CS, Su IJ, Powell KF, Croxson M, Foreman KE, Nickoloff BJ, Alkan S, Hayward GS. High-level variability in the ORF-K1 membrane protein gene at the left end of the Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus genome defines four major virus subtypes and multiple variants or clades in different human populations. J Virol. 1999;73:4156–4170. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.5.4156-4170.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]