Abstract

An unusual feature of lipid A from plant endosymbionts of the Rhizobiaceae family is the presence of a 27-hydroxyoctacosanoic acid (C28) moiety. An enzyme that incorporates this acyl chain is present in extracts of Rhizobium leguminosarum, Rhizobium etli, and Sinorhizobium meliloti but not Escherichia coli. The enzyme transfers 27-hydroxyoctacosanate from a specialized acyl carrier protein (AcpXL) to the precursor Kdo2 ((3-deoxy-D-manno-octulosonic acid)2)-lipid IVA. We now report the identification of five hybrid cosmids that direct the overexpression of this activity by screening ~4000 lysates of individual colonies of an R. leguminosarum 3841 genomic DNA library in the host strain S. meliloti 1021. In these heterologous constructs, both the C28 acyltransferase and C28-AcpXL are overproduced. Sequencing of a 9-kb insert from cosmid pSSB-1, which is also present in the other cosmids, shows that acpXL and the lipid A acyltransferase gene (lpxXL) are close to each other but not contiguous. Nine other open reading frames around lpxXL were also sequenced. Four of them encode orthologues of fatty acid and/or polyketide bio-synthetic enzymes. AcpXL purified from S. meliloti expressing pSSB-1 is fully acylated, mainly with 27-hydroxyoctacosanoate. Expression of lpxXL in E. coli behind a T7 promoter results in overproduction in vitro of the expected R. leguminosarum acyltransferase, which is C28-AcpXL-dependent and utilizes (3-deoxy-D-manno-octulosonic acid)2-lipid IVA as the acceptor. These findings confirm that lpxXL is the structural gene for the C28 acyltransferase. LpxXL is distantly related to the lauroyltransferase (LpxL) of E. coli lipid A biosynthesis, but highly significant LpxXL orthologues are present in Agrobacterium tumefaciens, Brucella melitensis, and all sequenced strains of Rhizobium, consistent with the occurrence of long secondary acyl chains in the lipid A molecules of these organisms.

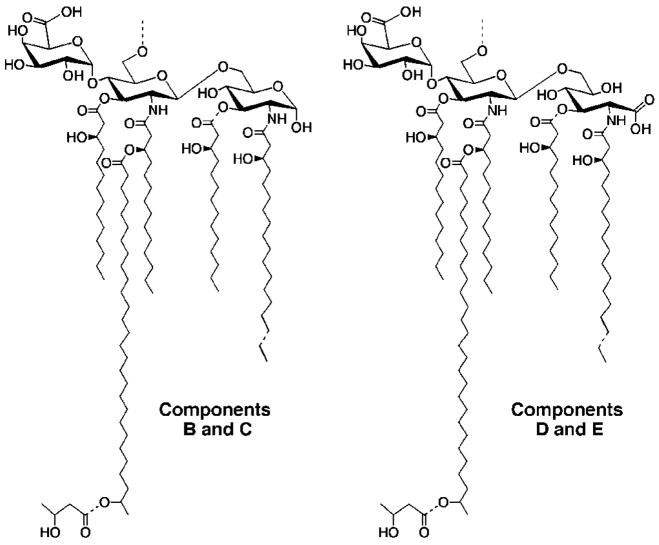

The lipid A moiety of lipopolysaccharide in the nitrogen-fixing endosymbionts, Rhizobium leguminosarum and Rhizobium etli, is very different compared with lipid A of other Gram-negative bacteria (1–3). Lipid A of R. elti CE3 consists of at least four related components (Fig. 1) (2, 3). The structural features that are distinct from other types of lipid A include the following: 1) the absence of phosphate groups at the 1- and 4′-positions (2–4); 2) the presence of a galacturonic acid residue at the 4′-position (2–4); 3) the presence of an unusual 27-hydroxyoctacosanoate chain (5) in acyloxyacyl linkage at position 2′(2, 3), modified with β-hydroxybutyrate; and 4) replacement in some species (2, 3) of the reducing end glucosamine unit with a 2-deoxy-2-aminogluconate residue (4) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Structures of the major lipid A molecular species present in R. etli CE3.

Components C and E are 3-O-deacylated derivatives of components B and D, respectively (2, 3).

Whether or not the remarkable lipid A species of R. leguminosarum and R. etli play a role in root cell infection and nodulation is unknown. It has been proposed that lipid A of Gram-negative plant pathogens (which is similar to that of Escherichia coli) may activate the innate immune system of plants just as E. coli lipid A activates innate immunity in animals (2, 3). The R. leguminosarum and R. etli lipid A species lack the structural features (i.e. the phosphate groups and the proper secondary acyl chains) needed for stimulation of innate immunity in animals (Fig. 1) (2, 3, 6). Structural modification of lipid A might allow the endosymbionts to avoid activating the plant immune system, thereby promoting bacteroid survival.

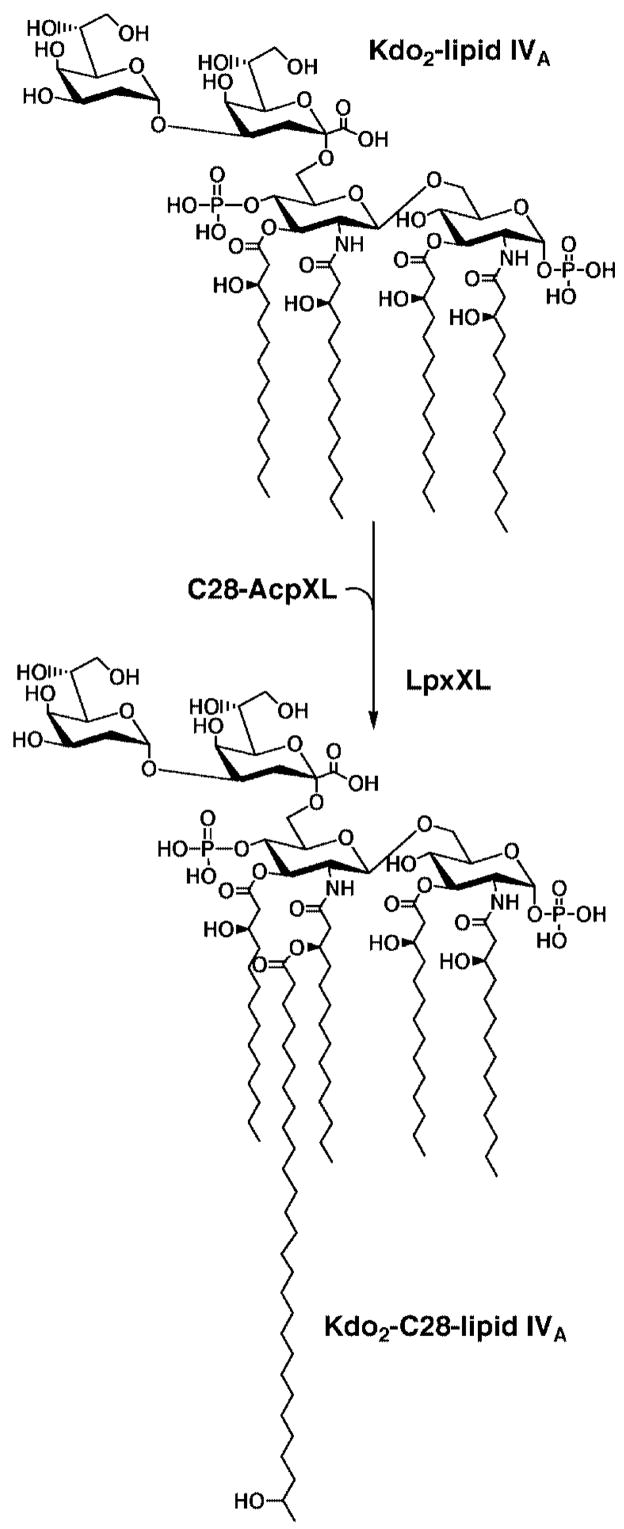

To evaluate the function of lipid A during symbiosis, a structure-activity study would be informative. The construction of mutant strains with defined alterations in lipid A structure requires a detailed understanding of the enzymology and genetics of lipid A biosynthesis. In previous studies (7), we have shown that the first seven enzymes of the lipid A pathway (1, 8), which generate the key intermediate Kdo21-lipid IVA (Fig. 2) in E. coli, are also present in R. etli and R. leguminosarum. However, additional enzymes are present in R. etli and R. leguminosarum (9, 10) to catalyze alternative processing of Kdo2-lipid IVA. Unique enzymes of R. etli and R. leguminosarum reported so far include the following: 1) phosphatases to remove the 4′- and 1-phosphate moieties of Kdo2-lipid IVA (9, 11, 12); 2) a deacylase to remove the ester-linked fatty acid at the 3-position (13); 3) a unique long chain acyltransferase that uses the special acyl carrier protein AcpXL to incorporate the 27-hydroxyoctacosanoic acid residue (Fig. 2) (10); and 4) a system for oxidizing the proximal glucosamine to aminogluconate (3). Enzymes for incorporating the 4′-galacturonic acid and β-hydroxybutyrate residues remain to be identified.

Fig. 2. Proposed acylation reaction catalyzed by LpxXL.

The seven enzymes that make Kdo2-lipid IVA in E. coli are also present in extracts of R. leguminosarum and R. etli (7), and the genes encoding them are found in single copy in the genomes of S. meliloti and M. loti (15, 47). In the LpxXL-catalyzed reaction, acylated AcpXL (but not AcpP) (10) serves as the acyl donor, supplying the 27-hydroxyoctacosanate moiety or the homologous C26 or C30 acyl chains if present. The attachment site for the 27-hydroxyoctacosanate chain generated enzymatically in vitro with Kdo2-lipid IVA as the acceptor has not yet been confirmed, but its attachment is Kdo-dependent (10). However, the proposed location of the 27-hydroxyoctacosanate chain is well established in the lipid A species isolated from cells of R. etli (2, 3).

We now describe the expression cloning of a 9-kb DNA fragment of R. leguminosarum that encodes the C28 acyltransferase, as well as proteins involved in the production of the C28 donor, ACP-XL. By assaying lysates (10) of individual members of a R. leguminosarum 3841 genomic cosmid library (14) harbored in Sinorhizobium meliloti 1021 (15), five clones overexpressing C28-acyltransferase activity were identified. The acyltransferase, which is detected using Kdo2-[4′-32P] lipid IVA as the acceptor (12, 16) (Fig. 2), is membrane-bound, whereas the donor substrate C28-AcpXL is soluble (10). Sequencing of the relevant DNA insert, which is the same in all five isolates, shows clustering of the genes encoding AcpXL and the long chain fatty acyltransferase (LpxXL) together with four other proteins related to enzymes involved in the fatty acid elongation and/or polyketide biosynthesis. Mass spectrometry of the AcpXL, purified from one of the above clones, shows that it is fully acylated with a long chain fatty acid. The R. leguminosarum lpxXL gene can be overexpressed in E. coli behind the T7 promoter, and the product is catalytically active. The availability of acpXL, lpxXL, and the other genes required to acylate AcpXL should facilitate the re-engineering of lipid A structures present in strains of E. coli and Rhizobium.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Chemicals and Materials

[γ-32P]ATP was obtained from PerkinElmer Life Sciences. Silica Gel 60 (0.25-mm) thin layer plates were purchased from EM Separation Technologies. Triton X-100 and bicinchoninic acid were from Pierce. Yeast extract and tryptone were purchased from Difco. All other chemicals were reagent grade and were obtained from either Sigma or Mallinckrodt. Restriction enzymes were from New England Biolabs, PCR reagents from Stratagene, shrimp alkaline phosphatase from U. S. Biochemical Corp., and custom primers and T4 DNA ligase from Invitrogen. All other reagents and enzymes were purchased from either Roche Molecular Biochemicals or Invitrogen.

Bacterial Strains and Growth Conditions

R. etli biovar phaseoli CE3, R. leguminosarum 3841, R. leguminosarum 8401, and S. meliloti 1021 (15) were described in previous studies (9, 11, 17). All Rhizobium and Sinorhizobium strains were grown at 30 °C in TY medium, which contain 5 g/liter tryptone, 3 g/liter yeast extract, 10 mM CaCl2, and 20 μg/ml nalidixic acid. For the growth of strains CE3 and 1021, streptomycin (200 μg/ml) was also added to the medium. The clones and subclones in S. meliloti 1021 were grown under additional selection with tetracycline (12.5 μg/ml). The Rhizobium cells were grown to A600 of 0.8 –1.2 before they were harvested.

Plasmid pET23b and E. coli strain BLR(DE3)pLysS were purchased from Novagen. BLR(DE3)pLysS/pET23b and BLR(DE3)pLysS/pSSB-101 were grown from a single colony in 1 liter of LB medium (18) (10 g/liter tryptone, 5 g/liter yeast extract, and 10 g/liter NaCl containing 100 μg/ml ampicillin) at 37 °C until A600 reached ~0.6. The cultures were then induced with 100 μg/ml isopropyl-1-thio-β-D-galatopyrano-side and incubated with shaking at 225 rpm for an additional 3 h at 37°C.

Preparation of Cell-free Extracts and Membranes

Mid-logarithmic phase cells were harvested by centrifugation at 8,000 × g for 15 min. All procedures were carried out at 0 –4 °C. The cell pellets were resuspended in 50 mM Hepes, pH 7.5, to give a final protein concentration of 5–10 mg/ml. To make crude cell extracts, the cells were broken by two passages through a French pressure cell at 18,000 pounds/square inch, and the debris was removed by centrifugation at 8,000 × g for 15 min. Membranes were prepared from the crude cell extracts by centrifugation at 149,000 × g for 60 min. The membrane pellet was suspended in 50 mM Hepes, pH 7.5, at a protein concentration of ~5–10 mg/ml, and the washed membranes were collected by another centrifugation at 149,000 × g for 60 min. The washed membranes were again suspended in 50 mM Hepes, pH 7.5, at a protein concentration of ~5–10 mg/ml. The soluble fraction from the initial centrifugation of the crude cell extract at 149,000 × g for 60 min was centrifuged a second time to remove residual membranes. Samples of washed membranes and membrane-free cytosol were stored in aliquots at −80 °C. Protein concentrations were determined by the bicinchoninic acid method (19) using bovine serum albumin as the standard.

Preparation of Radiolabeled Substrates

Kdo2-[4′-32P]-lipid IVA, Kdo-[4′-32P]-lipid IVA, and [4′-32P]-lipid IVA were prepared using the E. coli 4′-kinase and the appropriate Kdo transferase, as described previously (12, 20). Aqueous dispersions of these lipids were stored at −20 °C, and prior to use they were subjected to sonic irradiation in a bath sonicator for 90 s.

Assay of the C28 Acyltransferase

The reaction was carried out in 10 μl under optimized conditions at 30 °C for 10 min (32, 35) in 50 mM Hepes, pH 8.2, 0.2% Triton X-100, and 10 μM Kdo2-[4′-32P]-lipid IVA (20,000 –50,000 cpm/nmol). Various protein fractions were added as indicated. Following the incubation, 4-μl samples were withdrawn and spotted directly onto thin layer chromatography plates that were developed in the solvent chloroform/pyridine/88% formic acid/water (30: 70:16:10, v/v). Following overnight exposure to imaging screens, the extent of conversion of substrate to product was measured using a Amersham Biosciences model Storm PhosphorImager, equipped with ImageQuant software.

Screening of R. leguminosarum Genomic Library for C28 Acyltransferase Overproduction

The cosmid (pLAFR-1) (21) library of R. leguminosarum 3841 genomic DNA (~20 –25 kb) (14) in E. coli 803 host (22) was generously provided by Dr. J. Downie of the John Innnes Institute, Norwich, UK. It was not possible to assay colony lysates of the E. coli host directly, because R. leguminosarum promoters are not recognized in E. coli. Accordingly, the entire library was first transferred into S. meliloti 1021 by tri-parental mating (23). E. coli strain 803 harboring the cosmid library served as the cosmid donor, whereas E. coli MT616 (24) (the helper strain) provided the transfer functions.

S. meliloti 1021 (the recipient) was grown on TY agar with nalidixic acid (20 μg/ml) and streptomycin (200 μg/ml) selection for 24 h. E. coli strain 803 harboring the cosmid library was grown on LB agar containing tetracycline (12.5 μg/ml) for 12 h, and the E. coli MT616 helper strain was grown on LB agar with chloramphenicol (30 μg/ml) for 12 h. The bacteria were then scraped off from their respective plates and resuspended in TY medium (0.5 ml per plate) with no antibiotics. The S. meliloti 1021 (the recipient), the E. coli strain 803 harboring the cosmid library (donor), and the E. coli MT616 helper strain were mixed in a test tube in the approximate ratio of 3:1:1, v/v. A portion (0.5 ml per plate) of the mixture was then spread in a circular area (~5 cm diameter) on TY agar plate without antibiotic selection. Mating was allowed to take place for 24 –36 h at 30 °C. The mixture was scraped off the plate surface in TY medium containing 20% glycerol and then stored at −80 °C. The successful transfer of the cosmid library into S. meliloti 1021 was verified by analysis of the cosmids isolated from several randomly chosen transformed recipient colonies grown on a TY agar plate containing nalidixic acid (20 μg/ml), streptomycin (200 μg/ml), and tetracycline (12.5 μg/ml).

To examine a large number of S. meliloti 1021 cells harboring the individual members of the R. leguminosarum library in the pLAFR-1 cosmid, the glycerol stock of the mating mixture was thawed and appropriately diluted to obtain 50 –100 colonies per TY agar plate, supplemented with nalidixic acid (20 μg/ml), streptomycin (200 μg/ml), and tetracycline (12.5 μg/ml). The plates were incubated for 72 h at 30 °C to obtain individual colonies. For large scale screening, several thousand such colonies were re-grown one at a time for 24 h with constant shaking at 30 °C in separate wells of 96-well microtiter plates in 150 μl of TY medium, containing nalidixic acid (20 μg/ml), streptomycin (200 μg/ml), and tetracycline (12.5 μg/ml). A 50-μl portion of the culture from each well was transferred to another microtiter plate and stored as a 20% glycerol stock at −80 °C. The remaining cells were collected in each of the wells of the original microtiter plate by centrifugation at 3,660 × g for 15 min at 4 °C. The supernatants were decanted, and the cells were resuspended in 50 μl of 50 mM Hepes, pH 7.5. In order to generate concentrated lysates, the cells were broken by incubating with lysozyme (1 mg/ml) and EDTA (10 mM) for an hour at 4 °C (both added from concentrated stocks). Portions of the lysates (5 μl from each well) from four microtiter plates were combined to give 96 pools of four lysates in a fresh microtiter plate (20 μl per well final volume).

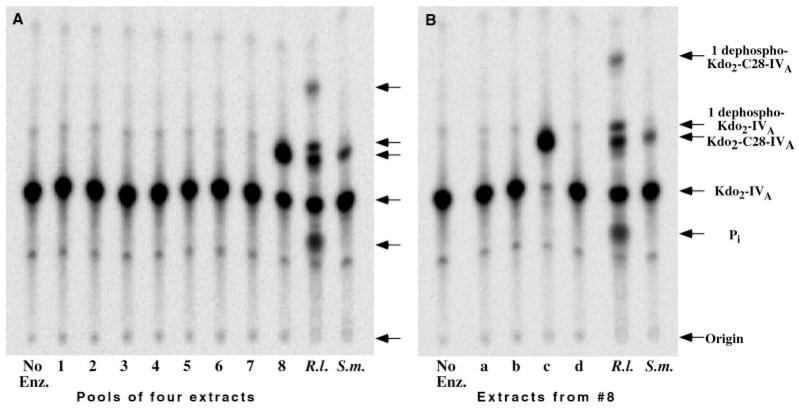

The pooled cell lysates were assayed for their ability to acylate Kdo2-[4′-32P]-lipid IVA in the following manner. A fresh 96-well micro-titer plate was prepared in which each well contained 2 μl of 250 mM Mes buffer, pH 6.5, 0.5% Triton X-100, 10 mM EDTA, 1.0 μM Kdo2-[4′-32P]-lipid IVA and 8 μl of pooled cell lysate, which was added last to give final volume of 10 μl. These plates were incubated at 30 °C for 2 h, and a portion of each reaction mixture (5 μl) was then spotted onto a Silica Gel 60 thin layer chromatography plate (Fig. 3A, lanes 1–8). A negative control reaction without enzyme (Fig. 3A, left lane) and positive controls containing either an R. leguminosarum 3841 or an S. meliloti crude extract (prepared by passage of cells through a French pressure cell) as the enzyme source were also spotted on each plate. The R. leguminosarum 3841 lysate provided standards for the various metabolites generated from Kdo2-[4′-32P]-lipid IVA in extracts of R. leguminosarum (Fig. 3, lane R.l.). The plates were developed in the solvent chloroform/pyridine/88% formic acid/water (30:70:16:10, v/v) and exposed to an imaging screen overnight. An Amersham Biosciences Storm Phosphor-Imager, equipped with ImageQuant software, was used to detect metabolism of the Kdo2-[4′-32P]-lipid IVA substrate to either more hydrophilic or more hydrophobic products. S. meliloti 1021/pSSB-1 was representative of several hybrid cosmids that directed overexpression of the long chain acyltransferase and was used for subcloning and DNA sequencing experiments.

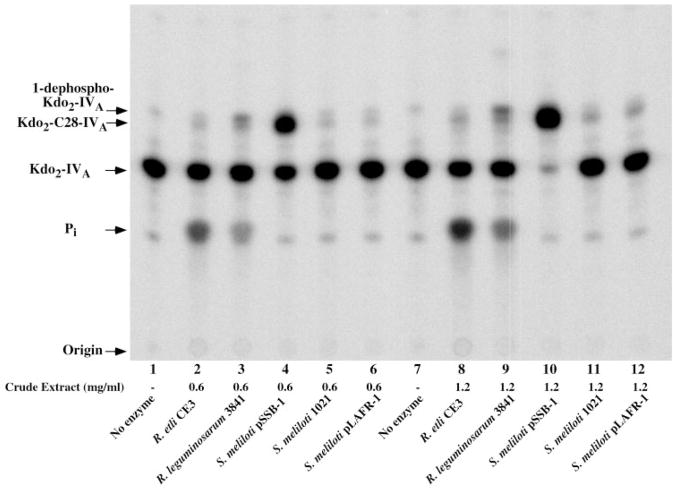

Fig. 3. Expression cloning of lpxXL from an R. leguminosarum DNA library in an S. meliloti host.

A shows an image of a thin layer plate from the initial screening assay, demonstrating a pool of four lysozyme/EDTA extracts that overexpresses Kdo2-[4′-32P]lipid IVA acylation activity (lane 8). The lane on the far left is the no enzyme control (No Enz.). The lanes designated R.l. are controls in which R. leguminosarum 3841 cell extract prepared by passage through a French pressure cell was used as the enzyme source, and the lanes labeled S.m. are similar S. meliloti 1021 control extracts. B, the four individual cell lysates (labeled a–d) that were used to make pool 8 in A were re-assayed, revealing that only extract c overexpresses the acyltransferase activity. The lane on the left is the no enzyme control (No Enz.). The position of the reaction product generated by the long chain (C28) acyltransferase, which is present at low levels in wild-type R. leguminosarum and S. meliloti extracts (9), is indicated on the right, along with the 1-phosphatase products. The 1-phosphatase is present only in R. leguminosarum extracts (9). The Pi is released by the 4′-phosphatase of R. leguminosarum (9, 11), which likewise is absent in S. meliloti.

Recombinant DNA Techniques

Plasmid and cosmid DNA were isolated using the Qiagen Spin Prep kit or a BIGGERprep kit (5 Prime → 3 Prime, Inc., Boulder, CO). Restriction endonucleases, shrimp alkaline phosphatase, and T4 DNA ligase were used according to the manufacturer’s instructions. DNA fragments were isolated from agarose gels using a Qiaex II gel extraction kit. All other techniques involving manipulation of DNA and cell transformation were done as described previously (25).

Plasmids or cosmids were introduced into S. meliloti by tri-parental mating, as outlined above for the library screening (23). E. coli strain 803 (22) or HB101 (Invitrogen) served as plasmid donors, and E. coli MT616 (24) provided the transfer function. Different strains of S. meliloti (see below) served as recipients.

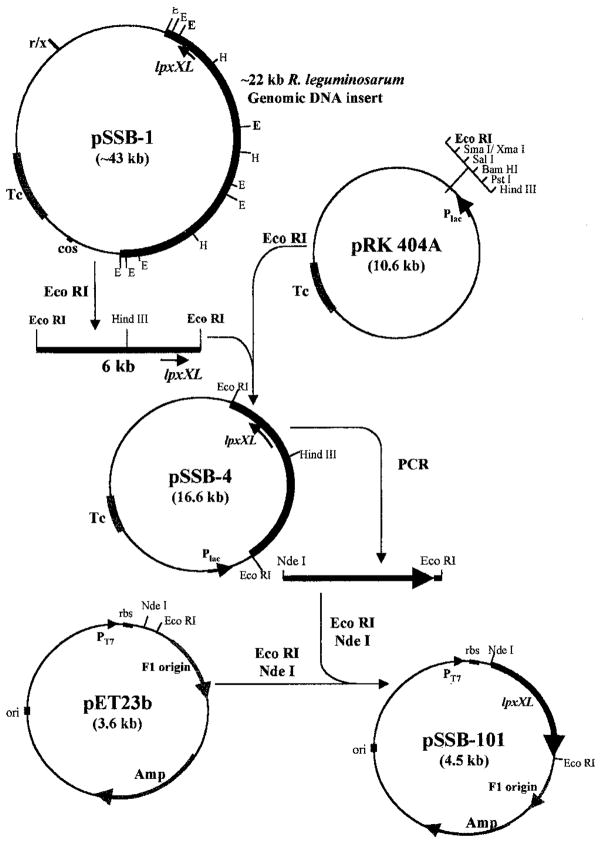

Subcloning the pSSB-1 Insert (~22 kb) and DNA Sequencing

The cosmid pSSB-1, isolated from the S. meliloti 1021/pSSB-1, was subjected to restriction digestion with EcoRI. This resulted in the release of several fragments (12.0, 6.0, 4.5, 0.8, 0.6, 0.4, 0.3, and 0.2 kb), including the ~21-kb linearized cosmid vector (pLAFR-1). Two EcoRI (6.0 and 4.0 kb) fragments and two HindIII (6.6 and 5.8 kb) fragments were selected for subcloning into the multiple cloning sites of the pRK404A shuttle plasmid (26). These restriction fragments were resolved by agarose gel electrophoresis and were purified directly from the gel. Each fragment was then ligated into pRK404A (Fig. 4). The ligation mixture was used to transform E. coli HB101. Plasmid-containing cells were selected by growth at 37 °C on LB agar supplemented with tetracycline (12.5 μg/ml). The plasmids isolated from several tetracycline resistance clones were also analyzed by restriction digestion to verify the presence of the right insert. The four plasmid constructs generated were designated as follows: pSSB-2, having the 5.8-kb HindIII DNA insert; pSSB-3, having the 4.0-kb HindIII DNA insert; pSSB-4, having the 6.0-kb EcoRI DNA insert; and pSSB-5, having the 4.0-kb EcoRI DNA insert.

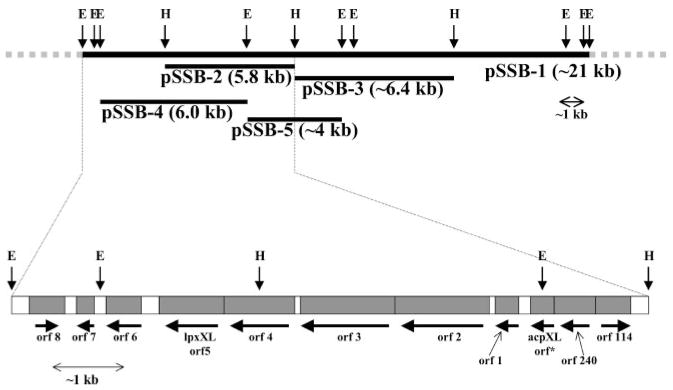

Fig. 4. Construction of plasmids pSSB-4 and pSSB-101 from pSSB-1.

The 6-kb EcoRI fragment of pSSB-1 was transferred into the broad range host vector, pRK404A (26), to generate pSSB-4. This construct was first transformed into E. coli HB101, verified by restriction mapping, and then transferred into S. meliloti 1021 by tri-parental mating. Similar procedures were used to construct pSSB-2, pSSB-3, and pSSB-5 (see Fig. 10). After sequencing of pSSB-1, a PCR product containing lpxXL (~960 bp in length) with appropriate restriction was ligated into the expression vector pET23b to generate pSSB-101, which was then transformed into competent cells of E. coli BLR(DE3)/pLysS (Novagen).

Each of these four plasmids was then transferred from E. coli HB101 into S. meliloti 1021, by tri-parental mating. S. meliloti 1021 recipient cells harboring pSSB-2, pSSB-3, pSSB-4, or pSSB-5 were selected on TY agar plates containing nalidixic acid (20 μg/ml), streptomycin (200 μg/ml), and tetracycline (12.5 μg/ml). Lysates prepared from these strains (16 colonies per construct) were screened in vitro for the over-expression of long chain acyltransferase activity.

Both strands of the DNA inserts in pSSB-2 and pSSB-4 (isolated on larger scale from their E. coli host strains) were sequenced at the Duke sequencing system facility using AmpliTaq DNA polymerase in conjunction with an ABI 377 Prism DNA Sequencer. Sequencing of the downstream region of orf6 (see below) was carried out using pSSB-1 as the template.

Expression of R. leguminosarum 3841 lpxXL Behind a T7 Promoter

A PCR-amplified DNA fragment containing the lpxXL gene was cloned into pET23b vector behind the T7 promoter (Fig. 4) (54, 55, 56). The forward PCR primer (5′-GCGCGTCATATGAAACTGTTCATCAC-CCG-3′) was synthesized with a clamp region, an NdeI restriction site, and a match of the coding strand starting at the translation initiation site. The reverse primer (5′-AGATAGAATTCCTAAGGCGCGAGCGT-CTGC-3′) was synthesized with a clamp region, an EcoRI restriction site, and a match to the anti-coding strand that included the stop codon. The PCR was performed using Pfu polymerase, as specified by the manufacturer. The plasmid pSSB-4 was used as the template. Amplification was carried out in a 50-μl reaction volume containing 100 ng of template, 20 mM Tris chloride, pH 8.8, 10 mM KCl, 10 mM (NH4)2SO4, 0.1% Triton X-100, 0.1% bovine serum albumin, 10 μM dNTPs, and 2 units of Pfu polymerase. The reactions were subjected to 25 cycles of denaturation (45 s, 94 °C), annealing (45 s, 55 °C), and extension (2 min, 72 °C) in a DNA thermal cycler. The reaction product was analyzed on a 1% agarose gel, was digested with NdeI and EcoRI, and was ligated into the expression vector pET23b that had been similarly digested. The resulting desired hybrid plasmid pSSB-101 was transformed into E. coli BLR(DE3)pLysS. The lpxXL DNA insert in pSSB-101 was confirmed by sequencing.

Chemical Hydrolysis of the LpxXL Reaction Product

Two reaction mixtures (10 μl each) were set up as described above with 2 μM Kdo2-[4′-32P]lipid IVA; reaction I contained no membrane or cytosol, and reaction II contained 200 μg/ml membrane proteins and 200 μg/ml cytosolic protein from S. meliloti 1021/pSSB-1. The reactions were incubated at 30 °C for 30 min to ensure almost complete conversion of the substrate to the product.

For mild base hydrolysis, 2 μl of each reaction mixture was combined with 18 μl of chloroform/methanol (2:1 v/v), and 2 μl of 1.25 M NaOH. The mixture was incubated at room temperature for 30 min, after which time 2 μl of 1.25 M HCl was added. After mixing, a 5-μl portion was applied to a thin layer plate.

For acid hydrolysis, 2 μl of each reaction mixture was combined with 18 μl of 0.1 M HCl in a 0.65-ml Microfuge tube, which was sealed with a clip. The tube was floated in a boiling water bath for 30 min. Next, 1.6 μl of 1.25 M NaOH and 2 μl of 10% SDS were added. A 5-μl sample was then applied to the thin layer plate.

For hydrolysis at pH 4.5, 2-μl of each reaction mixture was combined with 10 μl of 50 mM sodium acetate, pH 4.5, 2 μl of 10% SDS, and 3 μl of H2O. The tube was heated in a boiling water bath as described above. Following the incubation, a 5-μl portion was applied directly to the thin layer plate. This plate, containing all the samples described above, was then developed in the solvent chloroform/pyridine/88% formic acid/water (30:70:16:10, v/v) and exposed to an imaging screen overnight.

Partial Purification of C28-AcpXL from Wild-type R. leguminosarum 8401

A membrane-free cytosol prepared from R. leguminosarum 8401 (a 2-liter mid-log phase culture grown to A600 = 0.8) was used as the source of C28-AcpXL. Partial purification of C28-AcpXL was achieved using the first three steps of the procedure described by Brozek et al. (10): ultrafiltration through Centri-prep 100 and Centri-prep 50 membranes, heat treatment at 65 °C for 15 min, and DEAE-Sepharose column chromatography.

Purification of C28-AcpXL from S. meliloti 1021/pSSB-1

The purification of C28-AcpXL from the overproducing strain S. meliloti 1021/pSSB-1 was carried out at 4 °C. A cytosolic fraction was prepared from S. meliloti 1021/pSSB-1 cells (2-liter culture grown to A600 = 0.8). The cells were broken by two passages through a French pressure cell at ~5 mg/ml protein in 25 mM Hepes, pH 7.5, followed by centrifugation at 149,000 × g for 60 min. The membrane pellet was removed, and the ultracentrifugation was repeated with the supernatant to remove residual membrane fragments. The final cytosolic fraction, consisting of 135 mg of protein in 40 ml, was applied to a 15-ml DEAE-Sepharose column (Amersham Biosciences) that was equilibrated in 25 mM Hepes, pH 7.5. The flow-through was collected and re-circulated once through the column. Unbound proteins were then washed out with 25 mM Hepes, pH 7.5, containing 0.1 M NaCl, until A280 returned to base line. Elution was carried out with a 400-ml linear gradient from 0.1 to 0.5 M NaCl in 25 mM Hepes, pH 7.5. The fractions (4-ml each) were analyzed by native PAGE and also assayed for their ability to stimulate long chain acyltransferase activity together with washed membranes of R. leguminosarum 3841 as the source of long chain acyltransferase. The active fractions were pooled (~16 ml total), desalted, and concentrated (~25-fold) by centrifugation (3,660 × g) in a Millipore Ultrafree-15 centrifugal filter device (Biomax-30K NMWL membrane) at 4 °C. The concentrated material was diluted to 4 ml (~4.0 mg of protein/ml) with 25 mM Hepes, pH 7.5, and used for the next purification step.

The second anion-exchange chromatography was carried out with FPLC (Amersham Biosciences). The concentrated active fraction from the DEAE-Sepharose column was loaded onto an 8-ml Source-Q15 FPLC column (protein capacity 25 mg/ml and maximum pressure 750 pounds/square inch) (Amersham Biosciences), pre-equilibrated with 25 mM Hepes, pH 7.5. A flow rate of 3 ml/min was maintained during the chromatography. The column was washed for 10 min with 25 mM Hepes, pH 7.5, to remove unbound proteins, followed by a wash with 0.1 M NaCl in 25 mM Hepes, pH 7.5, for 40 min. The elution of proteins was carried out with a linear gradient from 0.1 to 0.3 M NaCl in 25 mM Hepes, pH 7.5, for 160 min. Elution with 0.3 M NaCl was continued for another 40 min, followed by 0.5 NaCl in 25 mM Hepes, pH 7.5, for 40 min. Four-ml fractions were collected. Fractions containing most of the AcpXL activity (total volume of 12 ml) were pooled and concentrated (~20-fold) by centrifugation (3,660 × g) in a Millipore Ultrafree-4 centrifugal filter device (Biomax-30K NMWL membrane) at 4 °C to a final volume of 0.6 ml (protein concentration of ~1.0 mg/ml).

Size-exclusion chromatography was used as the final purification step. The FPLC system (Amersham Biosciences) with a Superdex-200 HR10/30 gel filtration column (Amersham Biosciences) was used for this purpose. The concentrated active fraction (0.5 ml) from the Source-Q15 column was loaded onto the Superdex column, which was pre-equilibrated with 25 mM Hepes, pH 7.5. The column was developed with the same buffer for 48 min. A constant flow rate 0.5 ml/min was maintained, and 0.6-ml fractions were collected. The column fractions were analyzed as above. Active fractions were stored at −80 °C.

PAGE

Denaturing gel electrophoresis was carried according to Laemmli (27) using 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gels. For non-denaturing gel electrophoresis, 15% polyacrylamide gels were cast according to the conditions of Laemmli but without SDS. Samples were not denatured or reduced prior to loading. Electrophoresis was performed at a constant current of 25 mA, using a Tris glycine buffer without SDS. Gels were stained with Coomassie Blue. Polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis in the presence of 2.5 M urea was used to analyze samples of ACP and AcpXL, as described previously (28).

N-terminal Sequencing and Mass Spectrometry of Purified AcpXL

A sample (~10 μg in 300 μl) of purified AcpXL in 25 mM Hepes buffer, pH 7.5, was concentrated ~2-fold, and its buffer was exchanged with deionized water by using Microcon-30 device at 20,000 × g and 4 °C. The concentrated material was then diluted to the original volume with deionized water; the cycle was repeated three times. The final volume was 150 μl, and it contained 682 pmol of AcpXL, as estimated from the amino acid analysis of the sample.

N-terminal amino acid sequencing and mass spectrometry of purified AcpXL were carried out at the Harvard Microchemistry Facility by Dr. William S. Lane. The mass analysis was performed following a final fractionation on a 10-cm microcapillary system, packed with Porose 10R2 reverse-phase resin, that was interfaced with a Finnigan TSQ7000 triple quadrupole mass spectrometer, set up for electrospray ionization mass analysis (10, 29). Individual fractions from the microcapillary HPLC separation were analyzed. The uncharged intact molecular mass of the AcpXL was obtained by deconvolution of the spectrum.

RESULTS

Screening of a R. leguminosarum Genomic DNA Library for Kdo2-Lipid IVA-modifying Enzymes

Attempts to clone the R. leguminosarum long chain acyltransferase (Fig. 2) by PCR amplification of conserved sequences present in previously characterized lipid A late acyltransferase genes, such as lpxL or lpxM (30–32), or efforts to detect R. leguminosarum DNA restriction fragments by low stringency hybridization using E. coli lpxL as the probe, were unsuccessful. An expression cloning strategy was therefore developed. A cosmid library of R. leguminosarum 3841 genomic DNA (~20 –25-kb inserts) in pLAFR-1, harbored in E. coli 803, was transferred into S. meliloti 1021 by tri-parental mating. This was necessary because the E. coli transcription machinery does not efficiently recognize R. leguminosarum promoters. The screening procedure was designed to find clones directing the overexpression of the 4′-phosphatase, the 1-phosphatase, or the C28 late acyltransferase of R. leguminosarum (Fig. 3). Among extracts derived from ~4000 individual clones, we were in fact able to identify five that greatly overexpressed apparent C28 acyltransferase activity, using Kdo2-[4′-32P]lipid IVA as the acceptor. A typical result is shown in Fig. 3, in which extract c of pool 8 represents the desired hit. C28 acyltransferase was overexpressed more than 100-fold above the S. meliloti vector background and was easily detectable, even under the suboptimal assay conditions of the screening assay (Fig. 3). A key factor that contributed to the robust overexpression of C28 acyltransferase activity is the close linkage of the C28 acyltransferase and the acpXL structural genes, as determined by DNA sequencing of the insert (see below).

No clones overexpressing the 4′-phosphatase or the 1-phosphatase were detected among the ~4000 cosmids that were screened. These phosphatases may be toxic to S. meliloti, since its lipid A is phosphorylated, like that of E. coli (33).

The cosmids from the five clones directing the apparent overexpression the C28 acyltransferase were isolated. Based on their insert sizes (~22-kb by EcoRI -digestion) and restriction patterns (not shown), they appeared to be very similar. One of the clones was designated S. meliloti 1021/pSSB-1 and was further characterized. To confirm the screening results, crude extracts of late log phase cultures of S. meliloti 1021, S. meliloti 1021/pLAFR-1, S. meliloti 1021/pSSB-1, R. etli CE3, and R. leguminosarum 3841, prepared with a French press, were assayed under conditions optimized for C28 acyltransferase in wild-type cells. Comparable C28 acyltransferase activity was seen in all three parental strains (Fig. 5). The lipid A phosphatases were detected only in CE3 and 3841 extracts (Fig. 5). The vector pLAFR-1 had no effect on acyltransferase activity in S. meliloti 1021 extracts (Fig. 5, lanes 5 and 6 or lanes 11 and 12), but the hybrid cosmid pSSB-1 directed ~100-fold overexpression of acyltransferase activity (Fig. 5, lanes 4 and 10), even though no exogenous C28-AcpXL (10) was provided. Nearly complete conversion of 10 μM Kdo2-[4′-32P]lipid IVA to the putative product Kdo2-[4′-32P]C28-lipid IVA was seen after only 10 min (Fig. 5, lane 10) at an extract concentration of 1.2 mg/ml.

Fig. 5. The pSSB-1-driven overexpression of C28 acyltransferase activity in cell extracts of S. meliloti.

Kdo2-[4′-32P]lipid IVA acyltransferase activity in cell extracts of S. meliloti 1021/pSSB-1 was compared with that of wild-type R. leguminosarum, R. etli, S. meliloti 1021, or S. meliloti 1021 harboring the pLAFR-1 cosmid (the vector control). Reactions were carried out in 50 mM Hepes, pH 8.2, 0.2% Triton X-100, and 10μM Kdo2-[4′-32P]lipid IVA, with either 0.6 (lanes 2– 6) or 1.2 mg/ml (lanes 8 –12) of extract protein. After incubation for 10 min at 30 °C, 4-μl portions of each reaction were spotted onto Silica Gel 60 thin layer chromatography plate, which was developed in chloroform/pyridine/88% formic acid/water (30:70:16:10, v/v) and analyzed with a PhosphorImager.

Characterization of the S. meliloti 1021/pSSB-1 Reaction Product

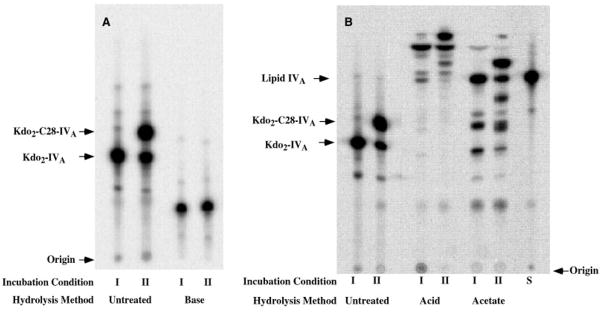

The rapidly migrating product generated by extracts of S. meliloti 1021/pSSB-1 (Fig. 5, lanes 4 and 10) was subjected to hydrolysis under mild alkaline (0.1 M NaOH), strong acid (0.1 M HCl at 100 °C), or mild acid (pH 4.5 at 100 °C) conditions. As shown in Fig. 6A, both the substrate and the product collapsed to the same slowly migrating species following mild alkaline hydrolysis, demonstrating that the putative C28 chain incorporated by extracts of S. meliloti 1021/pSSB-1 is attached to Kdo2-[4′-32P]lipid IVA via an ester linkage. Furthermore, the identical migration (Fig. 6A) following mild base treatment excludes the possibility of one dephosphorylation in extracts of S. meliloti 1021/pSSB-1. As indicated in Figs. 3 and 5, 1-dephospho- Kdo2-[4′-32P]lipid IVA migrates only slightly faster than Kdo2-[4′-32P]C28-lipid IVA. Hydrolysis of the product in 0.1 M HCl (34, 35) or 12.5 mM sodium acetate at 100 °C (36) (Fig. 6B) confirmed that the hydrophobic modification in the product generated by extracts of S. meliloti 1021/pSSB-1 is attached to the lipid IVA moiety and not to the Kdo or the 1-phosphate groups, which are both removed by hydrolysis in 0.1 M HCl. Furthermore, the C28 acyltransferase of S. meliloti 1021/pSSB-1 does not utilize [4′-32P]lipid IVA directly as a substrate (data not shown), consistent with the substrate specificity of other lipid A late acyltransferases, such as LpxL and LpxP (30, 37, 38). Taken together, the product analysis (Fig. 6) strongly suggests that S. meliloti 1021/pSSB-1 overexpresses only the C28 acyltransferase and not some other Kdo2-[4′-32P]lipid IVA-modifying enzyme.

Fig. 6. Hydrolysis of the LpxXL reaction product with base, acid, or sodium acetate buffer.

Incubation I is a control with authentic Kdo2-[4′-32P]lipid IVA. Incubation II shows the behavior of the product generated from Kdo2-[4′-32P]lipid IVA with the S. meliloti 1021/pSSB-1 cell extract. Portions of incubations I and II were hydrolyzed with either base (NaOH), acid (HCl), or pH 4.5 sodium acetate buffer, as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The products of these chemical treatments were analyzed by TLC, followed by PhosphorImager analysis. Panels A and B show results of separate experiments. S is authentic [4′-32P]lipid IVA.

Overexpression of Both AcpXL and LpxXL in S. meliloti 1021/pSSB-1

The long chain acyltransferase (LpxXL) of R. etli and R. leguminosarum is membrane-bound, but its donor substrate, C28-AcpXL, is cytoplasmic (10). Hence, the massive overexpression of the long chain acyltransferase activity seen in extracts of S. meliloti 1021/pSSB-1 (Fig. 5) in the absence of added C28-AcpXL suggested that pSSB-1 might encode both AcpXL and LpxXL or, alternatively, that the insert of pSSB-1 up-regulates S. meliloti LpxXL, S. meliloti AcpXL, or both.

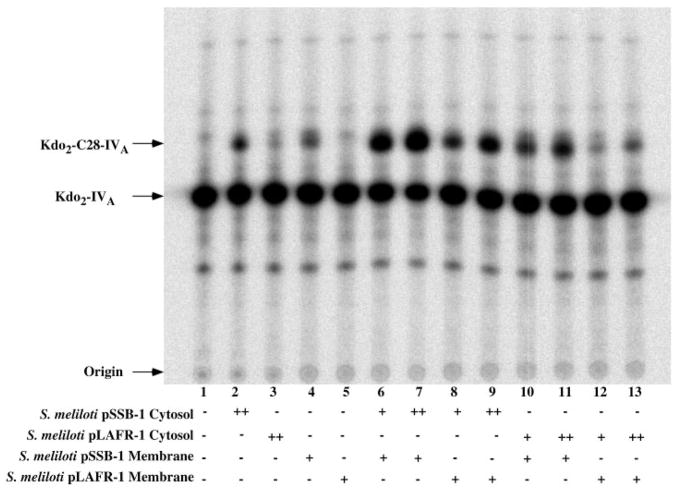

In order to address these possibilities, washed membranes (which are almost devoid of cytosolic proteins) and twice ultracentrifuged cytosol (which is largely depleted of membrane fragments) were assayed from S. meliloti 1021/pSSB-1 and S. meliloti 1021/pLAFR-1 (the vector control). The cytosol and membrane fractions were tested for their ability to support C28 acyltransferase activity by themselves or in various combinations (Fig. 7). As shown in lanes 1–5, cytosol or membranes by themselves displayed very little activity, with the S. meliloti 1021/pLAFR-1 fractions being virtually the same as the no enzyme control (lane 1). Importantly, the cytosol of S. meliloti 1021/pSSB-1 very efficiently stimulated LpxXL activity when incubated together with S. meliloti 1021/pLAFR-1 membranes, compared with S. meliloti 1021 pLAFR-1 cytosol (Fig. 7, lanes 8 and 9 versus lanes 12 and 13). Furthermore, the membranes of S. meliloti 1021/pSSB-1 were much more active than those of S. meliloti 1021/pLAFR-1, irrespective of the source of cytosol (Fig. 7, lanes 6, 7, 10, and 11 versus lanes 8, 9, 12, and 13). These findings strongly suggest that S. meliloti 1021/pSSB-1 overexpresses both a membrane-associated enzyme and a cytosolic factor needed for C28 acylation.

Fig. 7. Overexpression of both LpxXL and AcpXL in S. meliloti cells harboring pSSB-1.

Membrane-free cytosol fractions, prepared from S. meliloti 1021/pSSB-1 or from the vector control S. meliloti 1021/pLAFR-1, were assayed at 0.1 (+) or 0.2 (++) mg/ml protein. Washed membranes were assayed at 0.2 (+) mg/ml protein. The reaction mixtures were incubated at 30 °C for 10 min under standard conditions in the indicated combinations, and 4-μl portions were then spotted onto a silica gel thin layer plate to stop the reactions. Following chromatography, the plate was analyzed with a PhosphorImager.

To confirm that LpxXL is overexpressed in S. meliloti 1021/pSSB-1, washed membranes from selected strains were assayed in the presence of excess added AcpXL, which was purified from R. leguminosarum 8401 through the DEAE-Sepharose step, as described previously (10). About 5–7-fold higher LpxXL-specific activity (Table I) was detected in washed membranes of S. meliloti 1021/pSSB-1 versus matched membranes from various wild-type or vector control cells.

Table I. Overexpression of the membrane-bound long chain acyltransferase in S. meliloti 1021/pSSB-1.

The specific activity of the C28 acyltransferase activity was measured in presence of 0.2 mg/ml of partially purified AcpXL from R. leguminosarum 8401 (10) and double-washed membranes from indicated strains of Rhizobium.

| Strain | Specific activity |

|---|---|

| nmol/min/mg | |

| R. etli CE3 | 0.52 |

| R. leguminosarum 3841 | 0.63 |

| S. meliloti 1021 | 0.25 |

| S. meliloti 1021/pSSB-1 | 1.69 |

| S. meliloti 1021/pLAFR-1 | 0.23 |

Fractionation of membranes from S. meliloti 1021/pSSB-1 by isopycnic sucrose density gradient centrifugation (39) revealed that the C28 acyltransferase is localized exclusively in the inner membrane, as in wild-type R. leguminosarum 3841 and R. etli CE3 (data not shown), consistent with the involvement of an acyl-ACP donor.

Purification to Near-homogeneity of AcpXL Overexpressed in S. meliloti 1021/pSSB-1

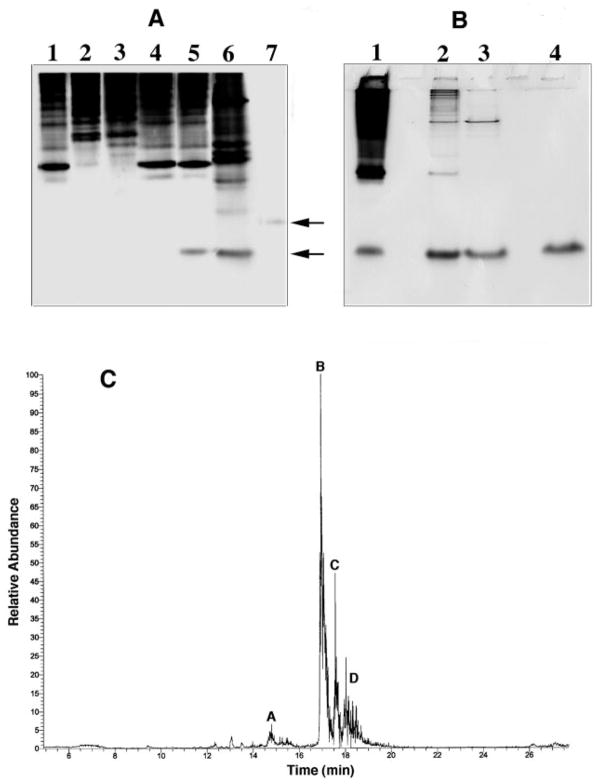

PAGE of the cytosolic proteins from S. meliloti 1021, R. leguminosarum 3841, R. etli CE3, S. meliloti 1021/pLAFR-1, and S. meliloti 1021/pSSB-1 (Fig. 8A) revealed massive overexpression of a protein in S. meliloti 1021/pSSB-1 (lane 6) that migrated with a standard preparation of C28-AcpXL (as indicated by the lower arrow). The putative AcpXL band was barely visible in the other strains (Fig. 8A, lanes 1–4). In S. meliloti 1021/pLAFR-1 an unknown band migrating just above AcpXL is seen, but careful inspection of the gel shows that this unknown is also present in the cytosol of S. meliloti 1021/pSSB-1 and may therefore be expressed from the vector itself.

Fig. 8. Purification and microcapillary HPLC analysis of acyl-AcpXL from S. meliloti 1021/pSSB-1.

A, this gel demonstrates overproduction of acyl-AcpXL in the cytosol of S. meliloti 1021/pSSB-1. Native PAGE was carried out as described under “Experimental Procedures” with 20 μg of cytosolic protein per lane followed by staining with Coomassie Blue; lane 1, S. meliloti 1021; lane 2, R. leguminosarum 3841; lane 3, R. etli CE3; lane 4, S. meliloti 1021; lane 5, S. meliloti 1021/pLAFR-1 (vector control); lane 6, S. meliloti 1021/pSSB-1; lane 7, E. coli AcpP. Lower arrow indicates acyl-AcpXL, and upper arrow E. coli AcpP. B, samples at different stages of the purification were analyzed by SDS-PAGE with 20 μg of protein per lane; lane 1, membrane-free cytosol of S. meliloti 1021/pSSB-1; lane 2, pooled active fractions from DEAE-Sepharose column; lane 3, pooled active fractions from Source-Q15 column; lane 4, pooled active fractions from Superdex-200 column. C, a sample of the purified acyl-AcpXL from S. meliloti 1021/pSSB-1 was fractionated on a microcapillary column packed with Porose 10R2. The column was interfaced with a Finnigan TSQ7000 triple quadrupole mass spectrometer for electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (29). Peaks A–D were analyzed as described in the text.

The massive overexpression of C28-AcpXL in S. meliloti 1021/pSSB-1 (Fig. 8A) facilitated the development of a simple purification procedure. Cytosol from S. meliloti 1021/pSSB-1 was loaded onto a DEAE-Sepharose column, and the proteins were eluted with a linear salt gradient. AcpXL emerged in a very sharp peak at 250 mM NaCl. The active fractions were pooled, desalted, and loaded onto a Source Q-15 FPLC column. AcpXL bound strongly and eluted at 200 mM NaCl. The pooled active fraction was passed through Sephacryl-200 column, and AcpXL was eluted as a discrete peak. The native gel electrophoresis analysis of the pooled fractions after each step is shown in Fig. 8B and clearly demonstrates that the AcpXL preparation is nearly homogeneous.

The identity and purity of the final AxpXL preparation was confirmed by N-terminal sequencing. The predominant sequence was TATFDKVADIIA, with a secondary sequence (MTATFDKVAD-I) attributed to a minor component in which the N-terminal methionine residue had not been removed. The observed sequence matched exactly the predicted amino acid sequence encoded by the acpXL structural gene of R. leguminosarum, as reported previously. Furthermore, the sequencing of AcpXL from S. meliloti 1021/pSSB-1 validated the idea that the pSSB-1 cosmid is not up-regulating S. meliloti AcpXL, but rather encodes R. leguminosarum AcpXL, since the predicted N-terminal sequence of S. meliloti AcpXL is MRVTATFDKVA-DIIA (15).

AcpXL Overexpressed in S. meliloti 1021/pSSB-1 Is Fully Modified with a C28 or C30 Hydroxyacyl Chain

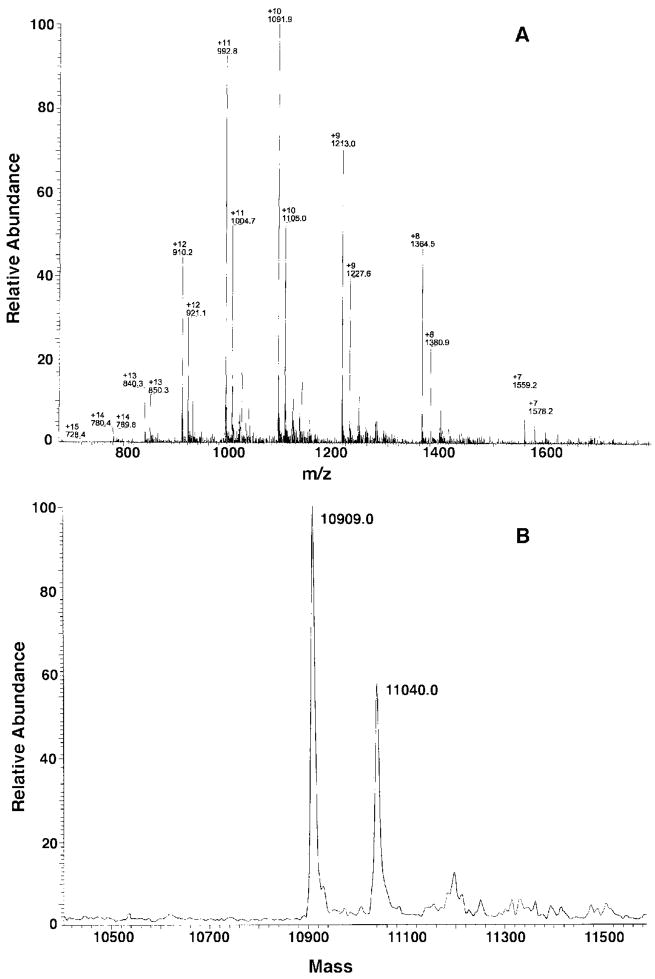

The purified AcpXL was resolved into two major components by microcapillary reverse phase HPLC (Fig. 8C, peaks B and D), representing over 95% of the total, and two minor species (Fig. 8C, peaks A and D). Each species was analyzed by electrospray ionization mass spectrometry. The spectrum of component B is shown in Fig. 9. When the observed spectrum (Fig. 9A) is deconvoluted (Fig. 9B), the predominant molecular weight (10909.0) matches the calculated molecular weight Mr of 10909.4 for an AcpXL species that lacks its N-terminal methionine but is derivatized with a 4′-phosphopantetheine and a 27-hydroxyoctacosanoic acid (C28) residue. A minor species (Fig. 9) is 131 atomic mass units larger, corresponding to the same modified protein in which the N-terminal methionine is retained, consistent with the amino acid sequence analysis.

Fig. 9. Mass spectrometry of the major acyl-AcpXL component isolated from S. meliloti 1021/pSSB-1.

A shows the mass spectrum of the major AcpXL component resolved by microcapillary HPLC (peak B in Fig. 8C). B is the deconvulated data from A, indicating the molecular weights of the two related acyl-AcpXL species present in peak B (Fig. 8C), differing by the presence or absence of the N-terminal methionine residue.

The predominant molecular weight Mr (10937.0) in the deconvoluted spectrum of peak C in Fig. 8C (data not shown) matches the calculated molecular weight Mr of 10937.4 for an AcpXL species, lacking its N-terminal methionine but containing a 4′-phosphopantetheine and a 29-hydroxytriacontanoic acid (C30) moiety. The mass for the minor component A seen in Fig. 8C was estimated to be 10484.0 (data not shown), consistent with an AcpXL species, lacking the N-terminal methionine and containing an unmodified 4′-phosphopantetheine moiety. No reliable mass spectrum could be obtained for peak D (Fig. 8C).

Experiments, similar to those described above, had been carried out previously (10) with AcpXL purified from wild-type R. leguminosarum. The latter consists of at least seven major fractions with holo-AcpXL as the major component (~40% of the total) and AcpXL acylated with 27-hydroxyoctacosanoic acid (C28) as the second most abundant species (~35%) (10). In contrast, our recombinant AcpXL consists mainly (>95%) of two acylated species (C28 and C30). It appears that all the holo-AcpXL molecules synthesized in S. meliloti 1021/pSSB-1 are rapidly acylated with (ω-1)-hydroxylated C28 or C30 acyl chains.

An in vivo system for producing a fully acylated acyl carrier protein in relatively high yields is unprecedented. A plausible explanation is that the proteins responsible for loading and extending nascent acyl chains on AcpXL are co-expressed in S. meliloti 1021/pSSB-1. Indeed, a number of open reading frames that resemble enzymes involved in fatty acid or polyketide biosynthesis are located near lpxXL on the pSSB-1 insert (see below).

Subcloning of the lpxXL Gene from the ~22-kb Insert of pSSB-1

Four overlapping fragments of the ~22-kb R. leguminosarum genomic DNA insert present in pSSB-1 were subcloned using either EcoRI or HindIII digestion (Fig. 10) into the pRK404A shuttle vector (Fig. 4). The resulting plasmids (pSSB-2, pSSB-3, pSSB-4, and pSSB-5) (Fig. 10) were then individually transferred from E. coli to S. meliloti 1021 by tri-parental mating. Compared with wild-type S. meliloti 1021 extracts, only the crude cell lysates of S. meliloti 1021 harboring either pSSB-2 or pSSB-4 exhibited high levels of acyltransferase activity. Further analysis of these subclones was carried out with membrane-free cytosol preparations and washed membranes. These assays (data not shown) showed that S. meliloti 1021/pSSB-2 overexpresses AcpXL in its cytosol but does not overexpress the membrane-bound acyltransferase, whereas S. meliloti 1021/pSSB-4 overexpresses only the long chain acyltransferase in its membranes (consistent with Fig. 10).

Fig. 10. Order of genes in the acpXL-lpxXL region of the R. leguminosarum chromosome.

Fragments of the ~22-kb DNA insert present in pSSB-1 were subcloned to make pSSB-2, pSSB-3, pSSB-4, and pSSB-5, all of which were sequenced. The dotted lines in the upper part of the figure indicate the ends of the sequenced regions of the insert in pSSB-1, in which there are 11 putative open reading frames that are transcribed in the indicated directions. The lengths of the inserts and the genes are drawn approximately to scale. Similar gene clusters extending from AcpXL to LpxXL are present in the sequenced genomes of A. tumefaciens, S. meliloti, M. loti, and B. melitensis (15, 45–48).

Gene Sequencing in the Vicinity of lpxXL and acpXL

DNA sequencing of the inserts in pSSB-2 and pSSB-4, as well as the downstream region around orf6 in pSSB-1 (Fig. 10), revealed 11 putative open reading frames. The complete nucleotide sequence relevant to the present paper has been submitted to the GenBank data base under accession number AF510733.

Tables II and III list some relevant homologues of the predicted polypeptides encoded by the 11 open reading frames (Fig. 10). The open reading frames orf114 and orf240 (Fig. 10) (Table III) had been described previously (10, 40). Comparison of the deduced amino acid sequence of orf114 with the translated genes from the data base did not reveal a statistically significant relationship to any other known protein. The orf240 gene product belongs to CRP/FNR family of transcriptional regulators (40). The sequence of the AcpXL coding region obtained from pSSB-3 is identical to the orf*/apcXL gene previously described (10, 40). Downstream of acpXL is a cluster of seven open reading frames that are transcribed in the same direction (Fig. 10). The proteins encoded by orf1, orf2, orf3, and orf4 have significant overall homology to enzymes involved in fatty acid or polyketide biosynthesis (Table III). Orf1 is highly homologous to (R)-3-hydroxyacyl-ACP dehydratase (FabZ), which is involved in saturated fatty acid biosynthesis (Table III) (41, 42). Orf2 and Orf3 are similar to one another, and they belong to the family of condensing enzymes of fatty acid biosynthesis (43). The protein encoded by orf3 is actually a closer homologue of polyketide synthase family than is the protein encoded by orf2 (Table III). Based on these sequence comparisons we speculate that the functions of Orf3 and Orf4 are related to the elongation of the C28 acyl chain on AcpXL.

Table II. Selected R. leguminosarum LpxXL orthologues and related proteins in the NCBI non-redundant database.

Homologues in the NCBI non-redundant data base were identified with the gapped BLASTp algorithm (61), using the predicted R. leguminosarum LpxXL protein sequence of 311 residues (accession number AAM 44299) as the probe against the NCBI protein data base.

| Organism | Homologya (Gaps) | E values |

|---|---|---|

| A. tumefaciensb | 227/254/309 | 10−129 |

| S. melilotib | 227/263/309 | 10−126 |

| B. melitensisb | 178/215/303 | 3 × 10−98 |

| M. lotib | 169/211/297 | 8 × 10−95 |

| R. prowazekii | 80/154/304 (15) | 2 × 10−31 |

| C. trachomatis | 84/119/309 (29) | 9 × 10−9 |

| E. coli LpxM(MsbB) | 70/109/265 (15) | 2 × 10−6 |

| E. coli LpxL(HtrB) | 69/118/301 (31) | <10−2 |

Homology is given as number of identities/number of positives/number of residues (including gaps) in the related segment when compared with R. leguminosarum LpxXL, a hypothetical protein of 311 amino acid residues. The number of gaps generally increases with increasing E values.

These organisms contain an AcpXL orthologue and a cluster of genes similar to that shown in Fig. 10.

Table III. Possible functions of genes in the vicinity of lpxXL and acpXL.

Homologies were determined using Gapped BLASTp (61) with the NCBI protein data base and are shown as percent identity/percent similarity/number of amino acids in the region of homology without low-complexity filtering. The number in parentheses indicates the size of the predicted or known polypeptide. A similar cluster of genes from acpXL to lpxXL is also present in A. tumefaciens, M. loti, S. meliloti, and B. melitensis, but these orthologues are not included in the above analysis since their functions have not been studied at the biochemical level.

| Predicted protein (no. aa) | Related protein with characterized function if any (no. aa) | Accession no. | Homology | ~E value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Orf114 (114) | Hypothetical protein of unknown function, R. leguminosarum (114) | S11952 | 100/100/114 | 10−55 |

| Orf240 (240) | Probable Fnr-type transcriptional regulator, R. leguminosarum (240) | P24290 | 100/100/240 | 10−126 |

| AcpXL/Orf* (109) | Specialized acyl carrier protein AcpXL, R. leguminosarum (92) | AAC32203 | 100/100/92 | 10−38 |

| Orf1 (124) | (3R)-Hydroxymyristoyl-ACP dehydratase, FabZ, E. coli (151) | P21774 | 33/45/116 | 103−7 |

| Orf2 (401) | 3-Oxoacyl-ACP synthase II (KAS II), FabF, E. coli (413) | P39435 | 22/39/263 | 10−3 |

| Orf3 (428) | 3-Oxoacyl-ACP synthase II (KAS II), FabF, E. coli (413) | P39435 | 33/49/417 | 10−51 |

| Orf4 (346) | Probable alcohol dehydrogenase, Aquifex aeolicus (343) | AAC07327 | 39/57/276 | 10−43 |

| Putative NADPH:quinone oxidoreductase, Arabidopsis thaliana (324) | BAB08996 | 36/52/250 | 10−30 | |

| Orf5/LpxXL (311) | Lipid A biosynthesis: Kdo2-lauroyl-lipid IVA acyltransferase, MsbB (LpxM), E. coli (323) | P24205 | 70/109/265 | 10−6 |

The predicted orf4 gene product (Table III) shows strong similarity over its length, excluding the N and C termini, to various oxidoreductases, dehydrogenases, and ketoreductase domains of polyketide synthases (44). Orf4 contains a glycine-rich sequence (GGSGIGTTAIQLAK) that matches the typical NAD-NADP-binding sequence motif.

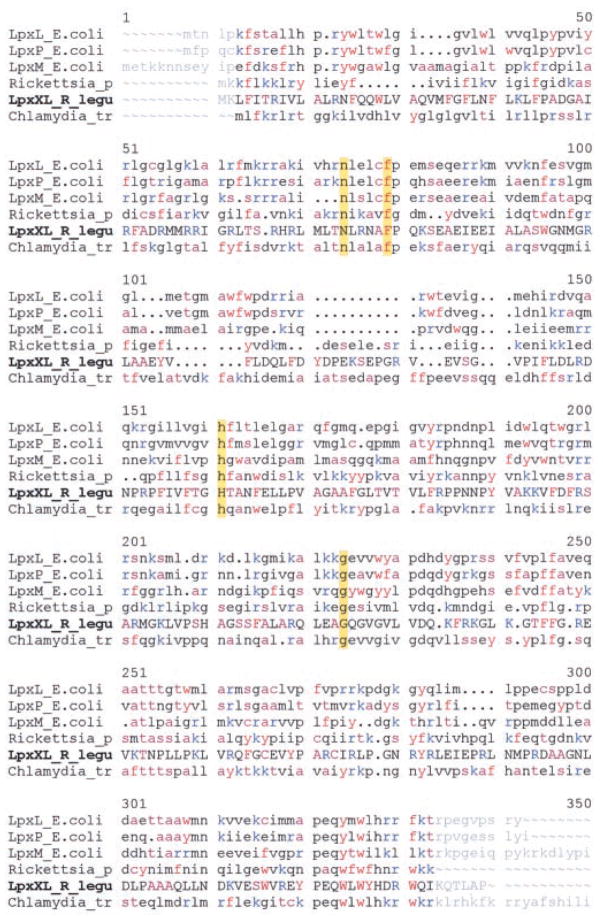

Meaningful albeit distant sequence similarities were found between Orf5 and various late acyltransferases involved in lipid A biosynthesis (Table II and Fig. 11) (1, 32). Aside from obvious Orf5 orthologues (Table II) present in Agrobacterium tumefaciens (45, 46), S. meliloti (15), Mesorhizobium loti (47), and Brucella melitensis (48), all of which make lipid A molecules modified with very long secondary acyl chains (5), Orf5 displayed the closest similarity to a putative late lipid A acyltransferase found in Rickettsia prowazelii (49), an organism that like R. leguminosarum also belongs to α2 subgroup of the proteobacteria (50). The relatively well characterized E. coli lauroyltransferase (lpxL) (30, 32, 38) is a distant homologue of Orf5 (Table II), but in a PSI-BLAST search the relationship is greatly accentuated (not shown). Indeed, multiple alignments of the distantly related lipid A late acyltransferases with Orf5 (Fig. 11) show that Asn-63, Phe-68, His-137, and Gly-200 (numbering of Orf5) are invariant in all these late acyltransferases, suggesting that these residues may play important roles in catalysis and/or folding. We therefore designate orf5 as lpxXL, the function of which is further validated as described below.

Fig. 11. Sequence alignments of LpxXL with distantly related late acyltransferases of lipid A biosynthesis.

The following abbreviations are used. LpxL_E.coli, E. coli lauroyltransferase involved in lipid A biosynthesis (GenBank™ accession number AAC74138); Lpx-P_E.coli, E. coli palmitoleoyltransferase involved in lipid A biosynthesis (GenBank™ accession number AAC75437); LpxM_E.coli, E. coli myristoyltransferase involved in lipid A biosynthesis (GenBank™ accession number AAC74925); Rickettsia_p, putative lipid A late acyltransferase from R. prowazekii (GenBank™ accession number CAA15149); LpxXL_R_legu, lipid A acyltransferase A described here; Chlamydia_tr, putative lipid A acyltransferase from Chlamydia trachomatis (Gen-Bank™ accession number AAC67600). Conserved amino acids are colored. The identical residues noted in yellow may form part of the active site. The C-terminal 122 residue extension of the C. trachomatis protein is not shown.

BLASTp searches with the predicted product of orf6 did not yield any obvious homologies to polypeptides of known function. Likewise, firm predictions of the biochemical functions of the proteins encoded by orf7 and orf8 were not possible.

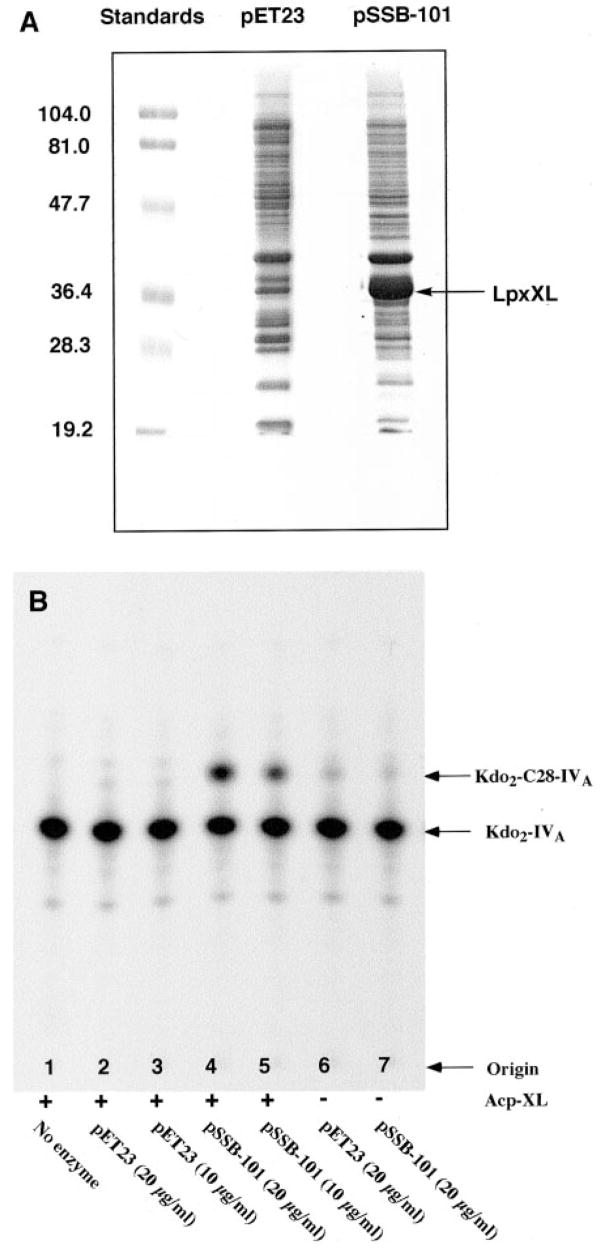

Heterologous Expression of LpxXL and Characterization of the Enzyme

Unequivocal demonstration that lpxXL encodes the long chain acyltransferase of R. leguminosarum is provided by heterologous expression in E. coli (Fig. 12A), extracts of which do not normally transfer the C28 chain of C28-AcpXL to Kdo2-[4′-32P]lipid IVA (Fig. 12B, lanes 2 and 3). However, washed membranes of E. coli BLR(DE3)/pLysS cells, expressing lpxXL behind the T7 promoter on plasmid pSSB-101, catalyze robust C28-AcpXL-dependent acylation of Kdo2-[4′-32P]lipid IVA (Fig. 12B, lanes 4 and 5 versus lanes 6 and 7). The C28 acyltransferase activity in membranes of E. coli BLR(DE3)pLysS/pSSB-101 has a pH optimum and a Triton X-100 requirement similar to that observed with the native C28 acyltransferase of R. leguminosarum (not shown). The recombinant enzyme is localized in the inner membrane, and the acylation reaction (Fig. 12B) is linearly dependent upon time and protein concentration (not shown). The recombinant acyltransferase requires the presence of two Kdo moieties in its acceptor substrate, as no activity is seen with lipid IVA or Kdo-lipid IVA (not shown). E. coli ACPs bearing 12–16-carbon acyl chains do not function as donors.

Fig. 12. Expression and assay of LpxXL in E. coli membranes.

A, SDS-PAGE of membrane proteins, prepared from isopropyl-1-thio-β-D-galactopyranoside-induced E. coli cells harboring either pSSB-101 or the vector control pET23b, was carried out with 20-μg samples of membrane protein per lane. These were run beside molecular weight standards, as indicated. B, the assays of recombinant LpxXL activity in E. coli membranes were performed in the presence or absence of 0.05 mg/ml purified AcpXL from S. meliloti 1021/pSSB-1, as indicated. Washed membranes from the pET23 vector control or the lpxXL expressing strain E. coli/pSSB-101 were added at 10 or 20 μg/ml. The reaction mixtures were incubated for 5 min at 30 °C, as described under “Experimental Procedures.”

The specific activity of the recombinant C28 acyltransferase in E. coli BLR(DE3)/pLysS/pSSB-101 membranes is 42 nmol/min/mg, which seems low given the high apparent level of protein expression (Fig. 12A). LpxXL activity can be quantitatively solubilized with Triton X-100, but a large fraction of the expressed LpxXL protein remains insoluble, suggesting that a portion of the overexpressed protein is not properly folded (not shown).

DISCUSSION

As shown in Fig. 2, R. leguminosarum membranes contain a Kdo-dependent C28 acyltransferase that utilizes the conserved lipid A precursor Kdo2-lipid IVA as its acceptor (9, 10). The enzyme does not function with 12–16 carbon acyl-ACPs derived from E. coli but, instead, requires its own dedicated acyl carrier protein, termed AcpXL (10). By using an expression cloning strategy, we have now identified an R. leguminosarum genomic DNA fragment containing a cluster of open reading frames involved in the incorporation of 27-hydroxyoctacosanoate into lipid A. This fragment includes the structural genes for the C28 acyltransferase LpxXL, the acyl carrier protein variant AcpXL, and several enzymes that may be involved in the biosynthesis of the (ω-1)-hydroxylated C28 acyl chain (5) that is attached to AcpXL (10) (Table III). Similar clusters are present in the genomes of M. loti (47), S. meliloti (15), and other proteobacteria (45, 46, 48) that contain AcpXL (Table II).

The R. leguminosarum LpxXL acyltransferase formally resembles the late lipid A acyltransferases LpxL, LpxM, and LpxP of E. coli in its strong preference for acceptor substrates containing a Kdo disaccharide (30, 31, 37, 38). However, attempts to clone the C28 acyltransferase using PCR amplification with primers designed from the lpxL gene, or detection of R. leguminosarum genomic DNA fragments by Southern hybridization with lpxL derived probes, were all unsuccessful, necessitating the expression cloning strategy shown in Fig. 3. Direct protein sequence comparisons (Tables II and Fig. 11) indicate that lpxL and lpxXL encode very distant orthologues, which presumably share a common catalytic mechanism despite their differences with respect to acyl chain length and Acp subtype specificity (10, 30). The T7 construct (Fig. 12) that directs overexpression of R. leguminosarum C28 acyltransferase activity in E. coli confirms that lpxXL is indeed the structural gene for the acyltransferase. This overproducing strain should also greatly facilitate the purification and characterization of the C28 acyltransferase.

Prior to the present work, the donor substrate for the C28 acyltransferase was not readily accessible, since the only source of C28-AcpXL was the cytosol of wild-type Rhizobium cells (10). However, large amounts of acyl-AcpXL were found to accumulate in S. meliloti 1021/pSSB-1, and a simple method for purification to near-homogeneity was devised (Fig. 8). Microcapillary HPLC followed by electrospray ionization mass spectrometry of the purified recombinant acyl-AcpXL (Figs. 8 and 9) revealed negligible amounts (<0.5%) of free AcpXL. About 60% of the protein is acylated 27-hydroxyoctasanoate (C28) and 40% with 29-hydroxytriacontanoate (C30).

The mass spectrometry of the recombinant acyl-AcpXL (Fig. 9) furthermore strongly suggests that the (ω-1)-hydroxy group is already in place prior to C28 transfer to Kdo2-lipid IVA (as proposed in Fig. 2). The stereochemistry and origin of the (ω-1)-hydroxyl group remains to be established. It is conceivable that this hydroxyl group is left intact during the initial steps in the biosynthesis of the long acyl chain on AcpXL. There may be a distinct set of enzymes that carry out the conversion of C2 to C4 on AcpXL, some of which might be encoded in the AcpXL/LpxXL gene cluster (Fig. 10). Alternatively, β-hydroxy-butyrate may be transferred directly from β-hydroxybutyryl-coenzyme A to free AcpXL. In either case, the dehydratase(s) of the fatty acid biosynthesis cycle (41–43, 51) are apparently unable to act on the 4-carbon β-hydroxylbutyryl chain intermediate attached to AcpXL.

As shown in Fig. 1, the (ω-1)-OH moiety of the C28 acyl chain present on mature R. leguminosarum or R. etli lipid A is itself further acylated with a β-hydroxybutyrate substituent (2, 3). However, there is no such moiety on the (ω-1)-OH moiety of the acyl-AcpXL isolated from wild-type R. leguminosarum cytosol or from S. meliloti 1021/pSSB-1. The origin of the pendant β-hydroxybutyrate group in R. leguminosarum lipid A (Fig. 1) is unknown. One interesting scenario is that the same β-hydroxybutyryl-AcpXL species that primes C28 biosynthesis also serves as the donor for the β-hydroxybutyrate cap.

Long acyl chains bearing a hydroxyl group at the γ-1-position are present in the lipid A molecules of all members of the Rhizobacae family (5) so far examined. Similar oxygenated acyl chains are also found on lipid A species from a number of other Gram-negative facultative intracellular organisms, such as B. melitensis and Legionella pneumophila (52, 53). The biological significance of such oxygenated long acyl chains remains elusive. Given that the number, distribution, and length of the secondary acyl chains on a lipid A molecule often influence the extent of immune stimulation (or inhibition) (6, 54), it may be that the C28 secondary acyl chain of Rhizobium lipid A likewise modulates the plant innate immune response, perhaps thereby facilitating symbiosis.

Relatively low endotoxic activity is observed in animal systems with lipopolysaccharides from L. pneumophila and Brucella abortus (55, 56). The long acyl chains of these lipopolysaccharides may interfere with toll receptor binding (57–59), or they may prevent digestion by host lipases (60). We have observed that the secondary 27-hydroxyoctacosanoate chain of R. leguminosarum or R. etli lipid A is not readily cleaved in vitro by the mammalian acyloxyacyl hydrolase (60) (data not shown).

Cloning of the C28 acyltransferase and the other putative genes related to the biosynthesis of the (ω-1)-hydroxylated long chain fatty acids on AcpXL paves the way for genetic studies of the biological significance of this unusual acyl chain. Characterization of the properties of Rhizobium mutants lacking one or more of these genes will be of special interest with respect to the efficiency of root infection, nodulation, and nitrogen fixation. An evaluation of the immunostimulatory and biophysical properties of C28-containing lipid A species may further help to explain the occurrence of this unique structure in Rhizobium lipid A. In preliminary experiments purified components B and D possess very low stimulatory activity in mouse cell cytokine production assays.2

The existence of an unusual lipid A species in plant endosymbionts like R. leguminosarum is intriguing given the recent identification of functional orthologues in all higher plants of the E. coli enzymes that synthesize the Kdo2-lipid IVA molecule (1). Although not yet identified as chemical entities, the putative plant-derived lipid A-like molecules may function in plant membrane assembly and/or in cell signaling, requiring that they be distinguished from lipid A species introduced by plant pathogens or plant endosymbionts.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. J. A. Downie (John Innes Institute) and Dr. P. Poole (University of Reading) for providing the R. leguminosarum genomic DNA cosmid library. We also thank Dr. D. Borthakur (University of Hawaii) for the pRK404A shuttle plasmid and Dr. R. Munford (University of Texas, Dallas) for the acyloxyacyl hydrolase.

Footnotes

This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health Grant R37-GM-51796 (to C. R. H. R.).

The nucleotide sequence(s) reported in this paper has been submitted to the GenBank™/EBI Data Bank with accession number(s) AF510733.

The abbreviations used are: Kdo2, (3-deoxy-D-manno-octulosonic acid)2; FPLC, fast protein liquid chromatography; HPLC, high pressure liquid chromatography; Mes, 4-morpholineethanesulfonic acid.

N. Que, S. Basu, C. Raetz, and S. Vogel, unpublished data.

References

- 1.Raetz CRH, Whitfield C. Annu Rev Biochem. 2002;71:635–700. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.71.110601.135414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Que NLS, Lin S, Cotter RJ, Raetz CRH. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:28006–28016. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004008200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Que NLS, Ribeiro AA, Raetz CRH. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:28017–28027. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004009200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bhat UR, Forsberg LS, Carlson RW. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:14402–14410. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bhat UR, Mayer H, Yokota A, Hollingsworth RI, Carlson R. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:2155–2159. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.7.2155-2159.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rietschel ET, Kirikae T, Schade FU, Mamat U, Schmidt G, Loppnow H, Ulmer AJ, Zähringer U, Seydel U, Di Padova F, Schreier M, Brade H. FASEB J. 1994;8:217–225. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.8.2.8119492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Price NPJ, Kelly TM, Raetz CRH, Carlson RW. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:4646–4655. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.15.4646-4655.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Raetz CRH. Annu Rev Biochem. 1990;59:129–170. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.59.070190.001021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brozek KA, Kadrmas JL, Raetz CRH. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:32112–32118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brozek KA, Carlson RW, Raetz CRH. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:32126–32136. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.50.32126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Price NJP, Jeyaretnam B, Carlson RW, Kadrmas JL, Raetz CRH, Brozek KA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:7352–7356. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.16.7352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Basu SS, York JD, Raetz CRH. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:11139–11149. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.16.11139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Basu SS, White KA, Que NL, Raetz CR. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:11150–11158. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.16.11150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ronson CW, Astwood PM, Downie JA. J Bacteriol. 1984;160:903–909. doi: 10.1128/jb.160.3.903-909.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Galibert F, Finan TM, Long SR, Puhler A, Abola P, Ampe F, Barloy-Hubler F, Barnett MJ, Becker A, Boistard P, Bothe G, Boutry M, Bowser L, Buhrmester J, Cadieu E, Capela D, Chain P, Cowie A, Davis RW, Dreano S, Federspiel NA, Fisher RF, Gloux S, Godrie T, Goffeau A, Golding B, Gouzy J, Gurjal M, Hernandez-Lucas I, Hong A, Huizar L, Hyman RW, Jones T, Kahn D, Kahn ML, Kalman S, Keating DH, Kiss E, Komp C, Lelaure V, Masuy D, Palm C, Peck MC, Pohl TM, Portetelle D, Purnelle B, Ramsperger U, Surzycki R, Thebault P, Vandenbol M, Vorholter FJ, Weidner S, Wells DH, Wong K, Yeh KC, Batut J. Science. 2001;293:668–672. doi: 10.1126/science.1060966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brozek KA, Hosaka K, Robertson AD, Raetz CRH. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:6956–6966. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cava JR, Elias PM, Turowski DA, Noel KD. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:8–15. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.1.8-15.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miller JR. Experiments in Molecular Genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; Cold Spring Harbor, NY: 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smith PK, Krohn RI, Hermanson GT, Mallia AK, Gartner FH, Provenzano MD, Fujimoto EK, Goeke NM, Olson BJ, Klenk DC. Anal Biochem. 1985;150:76–85. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(85)90442-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Garrett TA, Kadrmas JL, Raetz CRH. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:21855–21864. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.35.21855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Friedman AM, Long SR, Brown SE, Buikema WJ, Ausubel FM. Gene (Amst) 1982;18:289–296. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(82)90167-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wood W. J Mol Biol. 1966;16:118–133. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(66)80267-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Glazebrook J, Walker GC. Methods Enzymol. 1991;204:398–418. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)04021-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Finan TM, Kunkel B, De Vos GF, Signer ER. J Bacteriol. 1986;167:66–72. doi: 10.1128/jb.167.1.66-72.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ausubel FM, Brent R, Kingston RE, Moore DD, Seidman JG, Smith JA, Struhl K, editors. Current Protocols in Molecular Biology. John Wiley & Sons, Inc; New York: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ditta G, Stanfield S, Corbin D, Helinski DR. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1980;77:7347–7351. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.12.7347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Laemmli UK. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Post-Beittenmiller D, Jaworski JG, Ohlrogge JB. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:1858–1865. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chait BT, Kent SB. Science. 1992;257:1885–1894. doi: 10.1126/science.1411504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Clementz T, Bednarski JJ, Raetz CRH. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:12095–12102. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.20.12095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Clementz T, Zhou Z, Raetz CRH. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:10353–10360. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.16.10353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vorachek-Warren MK, Ramirez S, Cotter RJ, Raetz CRH. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:14194–14205. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200409200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Urbanik-Sypniewska T, Seydel U, Greck M, Weckesser J, Mayer H. Arch Microbiol. 1989;152:527–532. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Qureshi N, Cotter RJ, Takayama K. J Microbiol Methods. 1986;5:65–77. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Galloway SM, Raetz CRH. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:6394–6402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Caroff M, Tacken A, Szabó L. Carbohydr Res. 1988;175:273–282. doi: 10.1016/0008-6215(88)84149-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Carty SM, Sreekumar KR, Raetz CRH. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:9677–9685. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.14.9677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vorachek-Warren MK, Carty SM, Lin S, Cotter RJ, Raetz CRH. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:14186–14193. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200408200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kadrmas JL, Brozek KA, Raetz CRH. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:32119–32125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Colonna-Romano S, Arnold W, Schluter A, Boistard P, Pühler A, Priefer UB. Mol Gen Genet. 1990;223:138–147. doi: 10.1007/BF00315806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mohan S, Kelly TM, Eveland SS, Raetz CRH, Anderson MS. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:32896–32903. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Heath RJ, Rock CO. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:27795–27801. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.44.27795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Magnuson K, Jackowski S, Rock CO, Cronan JE., Jr Microbiol Rev. 1993;57:522–542. doi: 10.1128/mr.57.3.522-542.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Persson B, Zigler JSJ, Jornvall H. Eur J Biochem. 1994;226:15–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1994.tb20021.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Goodner B, Hinkle G, Gattung S, Miller N, Blanchard M, Qurollo B, Goldman BS, Cao Y, Askenazi M, Halling C, Mullin L, Houmiel K, Gordon J, Vaudin M, Iartchouk O, Epp A, Liu F, Wollam C, Allinger M, Doughty D, Scott C, Lappas C, Markelz B, Flanagan C, Crowell C, Gurson J, Lomo C, Sear C, Strub G, Cielo C, Slater S. Science. 2001;294:2323–2328. doi: 10.1126/science.1066803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wood DW, Setubal JC, Kaul R, Monks DE, Kitajima JP, Okura VK, Zhou Y, Chen L, Wood GE, Almeida NF, Jr, Woo L, Chen Y, Paulsen IT, Eisen JA, Karp PD, Bovee D, Sr, Chapman P, Clendenning J, Deatherage G, Gillet W, Grant C, Kutyavin T, Levy R, Li MJ, McClelland E, Palmieri A, Raymond C, Rouse G, Saenphimmachak C, Wu Z, Romero P, Gordon D, Zhang S, Yoo H, Tao Y, Biddle P, Jung M, Krespan W, Perry M, Gordon-Kamm B, Liao L, Kim S, Hendrick C, Zhao ZY, Dolan M, Chumley F, Tingey SV, Tomb JF, Gordon MP, Olson MV, Nester EW. Science. 2001;294:2317–2323. doi: 10.1126/science.1066804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kaneko T, Nakamura Y, Sato S, Asamizu E, Kato T, Sasamoto S, Watanabe A, Idesawa K, Ishikawa A, Kawashima K, Kimura T, Kishida Y, Kiyokawa C, Kohara M, Matsumoto M, Matsuno A, Mochizuki Y, Nakayama S, Nakazaki N, Shimpo S, Sugimoto M, Takeuchi C, Yamada M, Tabata S. DNA Res. 2000;7:331–338. doi: 10.1093/dnares/7.6.331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.DelVecchio VG, Kapatral V, Redkar RJ, Patra G, Mujer C, Los T, Ivanova N, Anderson I, Bhattacharyya A, Lykidis A, Reznik G, Jablonski L, Larsen N, D’Souza M, Bernal A, Mazur M, Goltsman E, Selkov E, Elzer PH, Hagius S, O’Callaghan D, Letesson JJ, Haselkorn R, Kyrpides N, Overbeek R. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:443–448. doi: 10.1073/pnas.221575398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Andersson SG, Zomorodipour A, Andersson JO, Sicheritz-Ponten T, Alsmark UC, Podowski RM, Naslund AK, Eriksson AS, Winkler HH, Kurland CG. Nature. 1998;396:133–140. doi: 10.1038/24094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bhat UR, Carlson RW, Busch M, Mayer H. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1991;41:213–217. doi: 10.1099/00207713-41-2-213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Denarie J, Debelle F, Prome JC. Annu Rev Biochem. 1996;65:503–535. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.65.070196.002443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zähringer U, Knirel YA, Lindner B, Helbig JH, Sonesson A, Marre R, Rietschel ET. Prog Clin Biol Res. 1995;392:113–139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zähringer U, Lindner B, Rietschel ET. In: Endotoxin in Health and Disease. Brade H, Opal SM, Vogel SN, Morrison DC, editors. Marcel Dekker, Inc; New York: 1999. pp. 93–114. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Golenbock DT, Hampton RY, Qureshi N, Takayama K, Raetz CRH. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:19490–19498. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Neumeister B, Faigle M, Sommer M, Zähringer U, Stelter F, Menzel R, Schutt C, Northoff H. Infect Immun. 1998;66:4151–4157. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.9.4151-4157.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rasool O, Freer E, Moreno E, Jarstrand C. Infect Immun. 1992;60:1699–1702. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.4.1699-1702.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Aderem A, Ulevitch RJ. Nature. 2000;406:782–787. doi: 10.1038/35021228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Alexander C, Rietschel ET. J Endotoxin Res. 2001;7:167–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lien E, Ingalls RR. Crit Care Med. 2002;30:1–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Munford RS, Hall CL. Science. 1986;234:203–205. doi: 10.1126/science.3529396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schaffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman DJ. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]