Abstract

To understand the role of structural elements of RNA pseudoknots in controlling the extent of -1 type ribosomal frameshifting, we determined the crystal structure of a high-efficiency frameshifting mutant of the pseudoknot from potato leaf roll virus (PLRV). Correlations of the structure with available in vitro frameshifting data for PLRV pseudoknot mutants implicate sequence and length of a stem-loop linker as modulators of frameshifting efficiency. Although the sequences and overall structures of the RNA pseudoknots from PLRV and beet western yellow virus (BWYV) are similar, nucleotide deletions in the linker and adjacent minor groove loop abolish frameshifting only with the latter. Conversely, mutant PLRV pseudoknots with up to four nucleotides deleted in this region exhibit nearly wild-type frameshifting efficiencies. The crystal structure helps rationalize the different tolerances for deletions in the PLRV and BWYV RNAs and we have used it to build a three-dimensional model of the PRLV pseudoknot with a four-nucleotide deletion. The resulting structure defines a minimal RNA pseudoknot motif composed of 22 nucleotides capable of stimulating -1 type ribosomal frameshifts.

RNA can fold into complex 3D structures that allow it to carry out its many biological functions, including regulation and catalysis (1,2). Pseudoknots (pkRNA) represent a very common folding motif (3) and have been observed in practically all types of naturally occurring RNAs (4). The minimal frameshift signal of -1 type translational recoding that is ubiquitous in pathogenic animal and plant viruses encompasses a heptanucleotide slippery sequence and a downstream stimulatory element, typically a pkRNA (5). Frameshifting allows the virus to control the relative expression levels of structural and enzymatic proteins vital to its life cycle (4). Identifying the physical features of pseudoknots that are important in stimulating frameshifting is of significant interest and requires information from related structures, both active and inactive. To interpret a vast body of frameshifting data for wild type (wt) potato leaf roll virus (PLRV) and a host of mutants (6) and to gain insight into similarities and differences between the pkRNAs from PLRV and a related luteovirus, beet western yellow virus (BWYV), that had previously been well characterized structurally (7) and functionally (8,9), we undertook a crystallographic analysis of PLRV pkRNA.

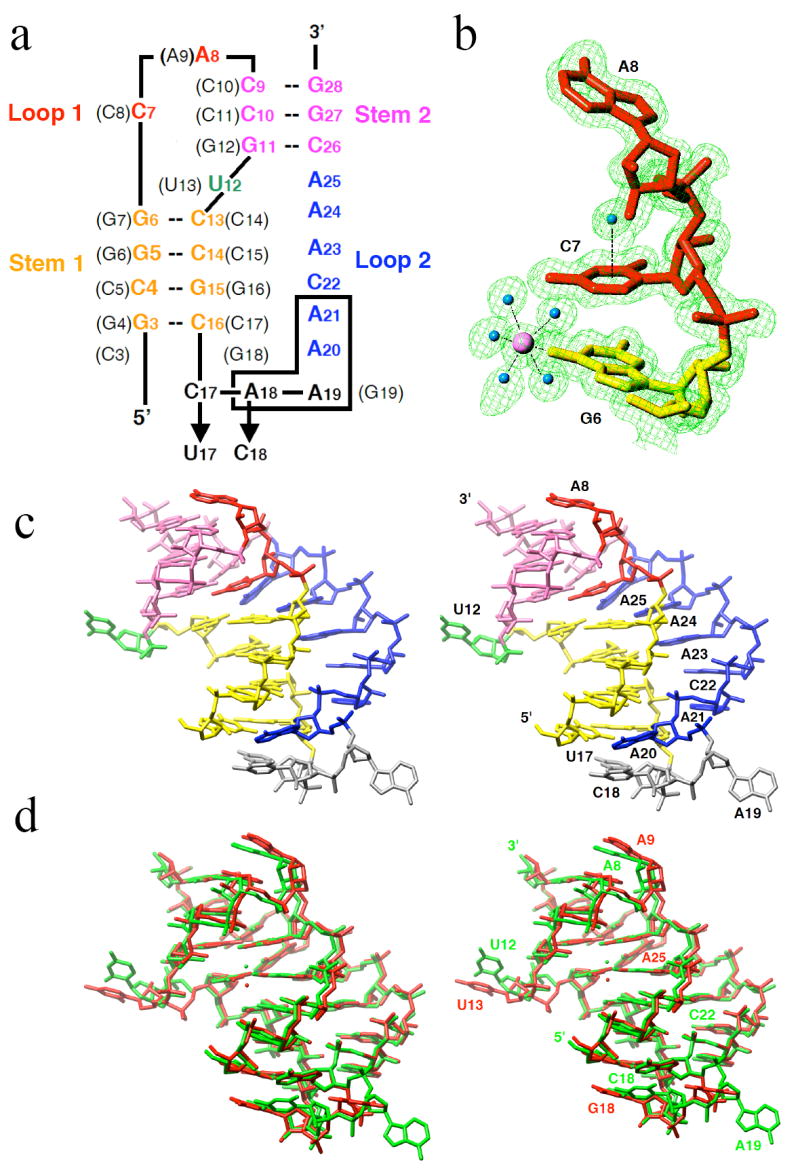

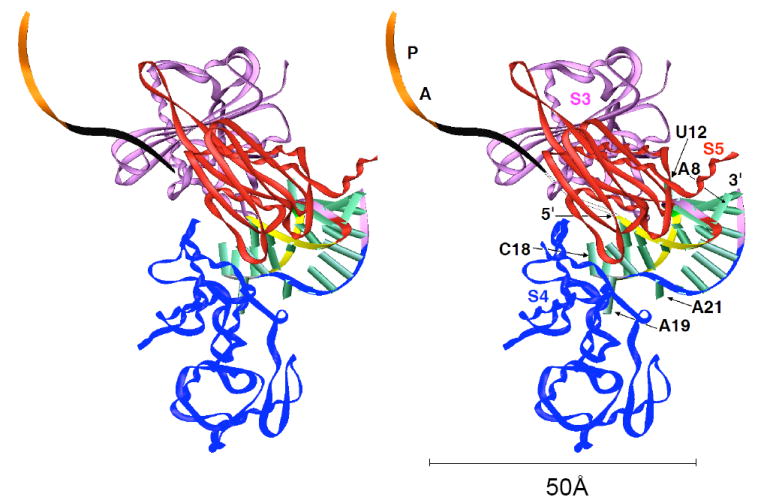

Here we present the crystal structure of the double-mutant PLRV pkRNA (C17U/A18C; Fig. 1a) that triggers the ribosomal -1 frameshift in vitro with an efficiency that is twice that for wt (wt 8.8%; ref. (6)). In the crystal, residues U17, C18 and A19 of the stem 1-loop 2 linker engage in hydrogen bonding or stacking interactions with nucleotides from neighboring molecules. However, in an isolated pseudoknot as part of a messenger RNA, their location on the surface of the molecule renders them available for interactions with the ribosome. Mutation or deletion of residues in the above linker for both PLRV and BWYV pkRNAs critically affects ribosomal frameshifting efficiency (6,8). The crystal structures demonstrate that the linker is positioned adjacent to the 5’-terminal nucleotide of the pseudoknot and thus will be one of the first features sensed by the ribosome as the message enters the downstream entry tunnel. Frameshifting is preceded by a pausing step, during which the pseudoknot is believed to lodge outside the tunnel as it is too bulky to enter it without partial or complete unwinding. Considering the now available structural and functional data for frameshifting pkRNAs from luteoviruses and the fact that no protein or nucleic acid factor that would mediate interactions between ribosome and mRNA pseudoknot has been identified to date, one may conclude that frameshifting involves direct interactions between mRNA pseudoknot and ribosome. Accordingly, particular nucleobases of the pseudoknot (i.e. those in the stem-loop linker) and side chains of proteins from the small subunit forming the entry site (S3, S4, S5) could interact, thus stifling the helicase activity of the ribosome (10) and causing it to pause. Although pseudoknots are not unique in stimulating pausing and frameshifts (11), the pseudoknot fold with its unusual arrangement of phosphate groups and looped-out bases on the surface probably constitutes a particularly challenging obstacle for the helix-unwinding ability of the ribosome.

FIGURE 1.

Nucleotide sequence and tertiary structure of the PLRV pseudoknot RNA. a, sequence and secondary structure of wt and mutant (indicated by arrows) PLRV pkRNAs. Nucleotide numbering and sequence in the BWYV wt-pkRNA are shown in parentheses. Deletion of boxed residues (A18-A21) maintains frameshifting comparable to that of PLRV wt-pkRNA. b, example of the quality of the final electron density: 2Fo-Fc sum map at the 1σ level. A Mg2+ and water molecules are shown as pink and cyan spheres, respectively. Note the water molecule centered above the protonated nucleobase of C7; c, stereo diagram of the crystal structure of PLRV pkRNA mutant C17U/A18C. d, stereo diagram depicting the superposition of PLRV (green) and BWYV pkRNAs (red; residue C3 was omitted). Coordinated Mg2+ ions are shown as spheres.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Crystallization and Data Collection

All RNA oligonucleotides were purchased from Dharmacon Inc. on a 1μmole synthesis scale, using the 2’-ACE protection group chemistry. Oligonucleotides were deprotected and desalted prior to crystallization. Typically, RNA at concentrations between 0.5 and 1 mM was annealed at 60°C with 2 mM spermine, cooled to r.t., and then stored overnight at 4°C. Crystals of size 0.3 × 0.1 × 0.05 mm for the PLRV pkRNA C17U/A18C double mutant were grown at 18°C from 100 mM Mg(OAc)2, 10% (v/v) PEG8000, 50 mM sodium cacodylate, pH 6.5, by the sitting drop vapor diffusion method. Crystals were soaked in mother liquor containing 25% glycerol as the cryo-protectant for about 1 minute, frozen and used for data collection. The crystals have the space group P3221 and diffracted to 1.35 Å resolution. Separate low- and high-resolution data sets were collected for a single crystal on the 5 ID beam line of the DND-CAT at the Advanced Photon Source (Argonne, IL) using a MAR225 detector. All data were processed with the program XDS (12), and selected crystal data and data collection parameters are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Selected Crystal Data and Refinement Parameters

| Space group | Trigonal P3221 |

|---|---|

| Unit cell constants [Å] | a = b = 53.25 Å, c = 55.00 |

| Resolution [Å] | 1.35 |

| Number of unique reflections | 19,098 |

| Completeness (1.40 – 1.35 Å) [%] | 96.0 (84.9) |

| R-merge (1.40 – 1.35 Å) [%] | 4.0 (26.4) |

| R-work [%] | 11.4 |

| R-free [%] | 19.0 |

| No. of refinement parameters | 6,955 |

| Data to parameter ratio | 2.75 |

| No. of restraints | 7,095 |

| No. of water molecules | 230 |

| R.m.s.d. bond lengths [Å] | 0.022 |

| R.m.s.d. bond angles (1-3 dist.) [Å] | 0.041 |

Structure Solution and Refinement

The structure was determined by the Molecular Replacement technique with the program MOLREP (13), using the BWYV pkRNA structure (7) without looped-out and capping residues as a starting model. Several regions were manually rebuilt and the initial refinement was carried out with the program CNS (14). Nucleotides in the stem1-linker-loop 2 and capping regions that were absent in the original model were built into omit electron density maps, using the program TURBO FRODO (15). Further positional and anisotropic B-factor refinements were carried out with the program SHELX97 (16), setting aside 5% of the reflections to calculate the R-free (17). Final refinement parameters and root mean square deviations from ideal geometries are listed in Table 1.

Circular Dichroism Experiments

Circular dichroism experiments were carried out using an Aviv 215 Spectrometer. RNA samples (~5 mM in 1 mL) were prepared in 20 mM Na2HPO4 (pH 7.0), 150 mM NaCl and 2 mM MgCl2. Initially, wavelength spectra from 350–200 nm were recorded at 25°C. Samples were then cooled to 2°C and slowly heated from 2 to 100°C in 2°C/min steps, while ellipticity was monitored at 267 nm. After the temperature was held constant at 100°C for 2 min, samples were re-cooled to 25°C and another wavelength spectrum was collected. The heating/cooling rates were 2°C per min, with 0.5 min equilibrations at each temperature. Following temperature equilibration, ellipticity data were collected for a 10 sec period. Melting temperatures Tm for overall transitions were obtained from first derivatives of plots of the averaged ellipticity at 222 nm versus temperature.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Crystal Structure of a PLRV pkRNA Mutant

Guided by the extensive in vitro frameshifting data for mutants of PLRV pkRNA (6), we selected 14 RNA sequences with lengths of between 22 and 27 nucleotides for chemical synthesis and crystallization. Crystals were obtained for three of the RNAs, but only those of the high-efficiency frameshifting double-mutant (C17U/A18C; Fig. 1a) were of diffraction quality. The structure of the 26-nucleotide pseudoknot was determined using the BWYV pkRNA (7) as a model and crystallographic refinement against all data up to a resolution of 1.35 Å resulted in a final R-factor of 11.4% (R-free = 19.0%). Selected crystal data, data collection and refinement parameters are presented in Table 1. An example of the quality of the final electron density is shown in Fig. 1b and a stereo diagram depicting the three-dimensional structure of the PLRV pkRNA mutant is shown in Fig. 1c.

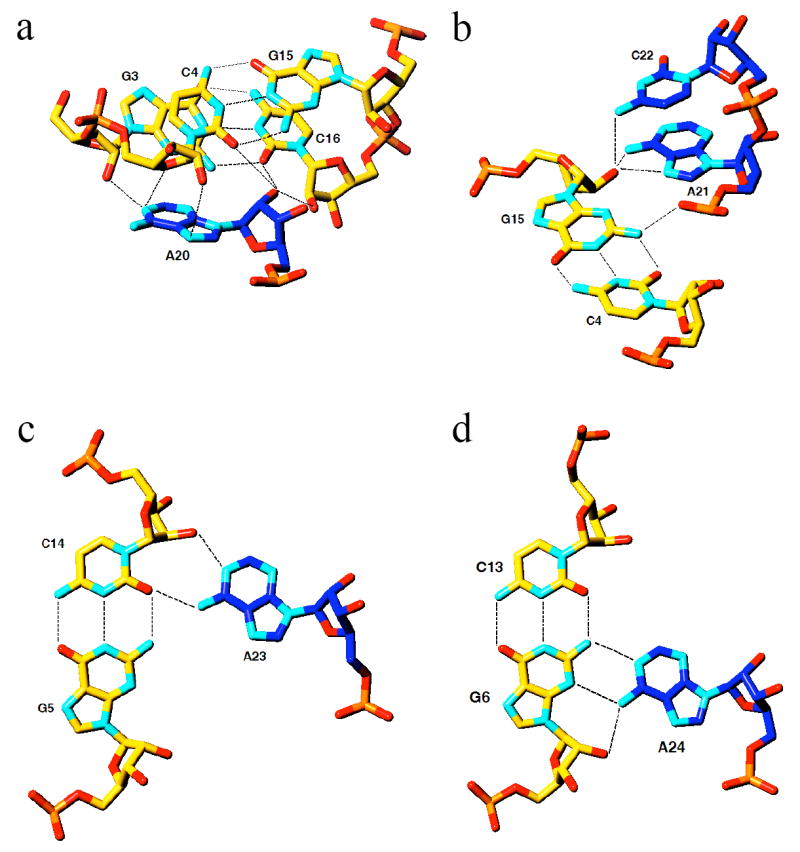

The overall structure of the PLRV pkRNA (the above mutant; the wild type will be referred to as wt-pkRNA in the further discussion) shows close resemblance to that of the previously determined crystal structure of a 28-nucleotide BWYV pkRNA (7). It should be noted that stem 1 of the PLRV pkRNA is one base pair shorter and loop 2 two residues longer compared with BWYV pkRNA (Fig. 1a). A stereo diagram of the superposition of the three-dimensional structures of the PLRV pkRNA mutant and the BWYV wt-pkRNA is depicted in Fig. 1d. Similarities between the two structures include the relative orientation of stem 1 and stem 2 (7), the looping-out of U12 (U13 in BWYV; residues in parentheses below refer to the BWYV pkRNA), and coordination of a Mg2+ ion at the interface between stem 1 and stem 2 (18) that is likely important for thermodynamic stabilization of the pseudoknot (19). The shift between the Mg2+ positions in the two structures amounts to 1.9 Å. Further shared features are the quadruple base interaction of the protonated cytidine C7 (C8) (7,20) with the G11:C26 pair (G12:C26) and A25, including an unusually closely spaced water atop the cytosine base (Fig. 1c) (21), and the minor groove triplex formed by loop 2 residues A20 to A25 with base pairs of stem 1 (Fig. 2). Selected tertiary hydrogen bonding interactions in the PLRV pkRNA are summarized in Table 2. Mutation of C7 (C8) and any of the six residues in loop 2 in the PLRV pkRNA drastically reduced the extent of frameshifting (6), matching earlier findings in the case of BWYV (8) and confirming the importance of sequence-specific interactions between nucleotides of stems and loops.

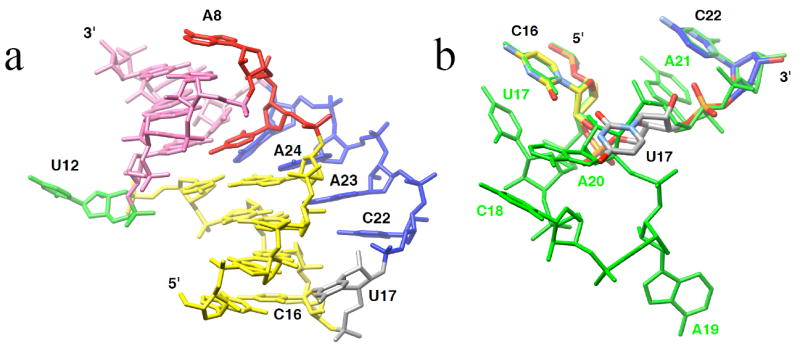

FIGURE 2.

Interactions of loop 2 nucleotides with stem 1 base pairs (carbon atoms colored in blue and yellow, respectively). Formation of the minor groove triplex is RNA-specific as 2’-hydroxyl groups are involved at every level. a, A20 interacts with two base pairs of stem 1 (G3:C16 and C4:G15), and multiple hydrogen bonds involving 2’-hydroxyl groups can be clearly seen. b, interactions between A21/C22 and C4:G15. c, Interaction between A23 and G5:C14. d, interaction between A24 and G6:C13. Note that loop 2 (blue) moves from one strand of stem 1 to the other between A21 and A24.

Table 2.

Tertiary H-bonds in the Minor Groove Triplex

| Interacting nucleotides | Distance [Å] | |

|---|---|---|

| Loop 2 | Stem 1 | |

| A20 2’-OH | C16 2’-OH | 2.63 |

| A20 2’-OH | C4 O2 | 3.53 |

| A20 N7 | C4 2’-OH | 3.29 |

| A20 N6 | C4 O4’ | 3.54 |

| A20 N3 | G3 N2 | 2.99 |

| A20 N1 | C4 O4’ | 3.04 |

| A21 N6 | G15 3’-O | 3.32 |

| A21 N6 | G15 2’-OH | 2.89 |

| A21 N7 | G15 2’-OH | 2.89 |

| C22 N4 | G15 2’-OH | 3.23 |

| A23 N1 | C14 2’-OH | 2.71 |

| A23 N6 | C14 O2 | 2.92 |

| A23 N6 | G5 N2 | 3.42 |

| A24 N6 | G6 2’-OH | 2.97 |

| A24 N6 | G6 N3 | 3.04 |

| A24 N1 | G6 N2 | 3.03 |

| A25 N1 | C13 2’-OH | 2.58 |

| A25 N6 | G6 N2 | 3.55 |

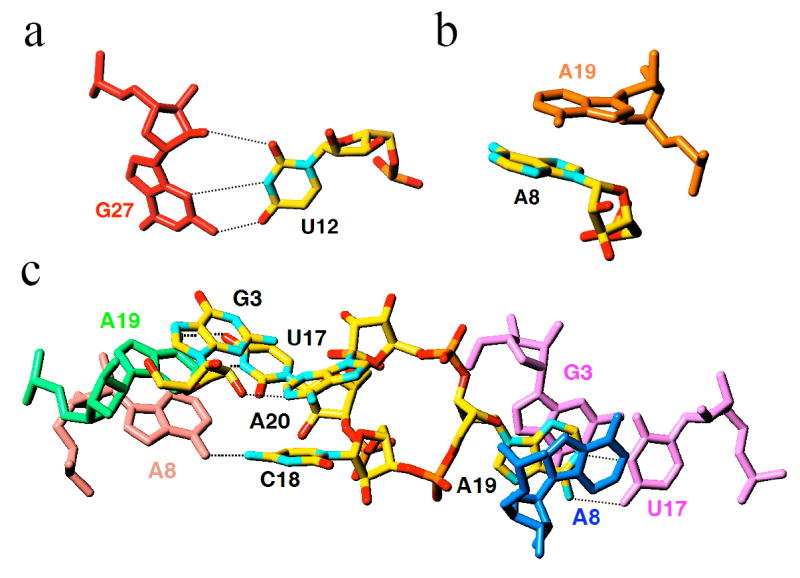

The structural and functional homologies between the pkRNAs from PLRV and BWYV discussed above do not include the linker region between stem 1 and loop 2 (Fig. 1). The structure of the PLRV pkRNA mutant now confirms that the linker is indeed comprised of three nucleotides instead of the single nucleotide (G19) in the BWYV pkRNA. Residue U17 stacks on C16 from the terminal base pair of stem 1, whereas both C18 and A19 are looped out and extend away from the triplex region (Fig. 1b). Together with U12 (Fig. 3a) and A8 (Fig. 3b), these residues are involved in intermolecular contacts in the crystal lattice of the pseudoknot. The nucleobases of both C18 and A19 stack on residues from symmetry-related pseudoknot molecules (Fig. 3c). Residue A20 anchors the loop 2 in the minor groove of stem 1. In addition to being engaged in multiple hydrogen bonds involving base and sugar moieties (Fig. 2), A20 also stacks on C18 (Fig. 3c).

FIGURE 3.

Lattice interactions in crystals of PLRV pseudoknot RNA. Nucleotides of individual pseudoknot molecules (carbon atoms of the reference pkRNA are colored in yellow) involved in inter-molecular interactions include a, the looped-out U12, b, the A8 cap, and c, residues of the linker between stem 1 and loop 2. Residues from symmetry-related pseudoknot molecules are colored differently and are labeled, and hydrogen bonds are thin dashed lines.

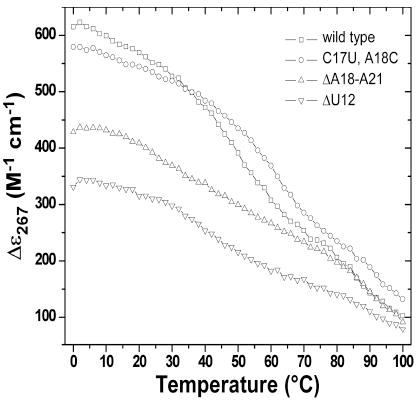

Structure and Activity

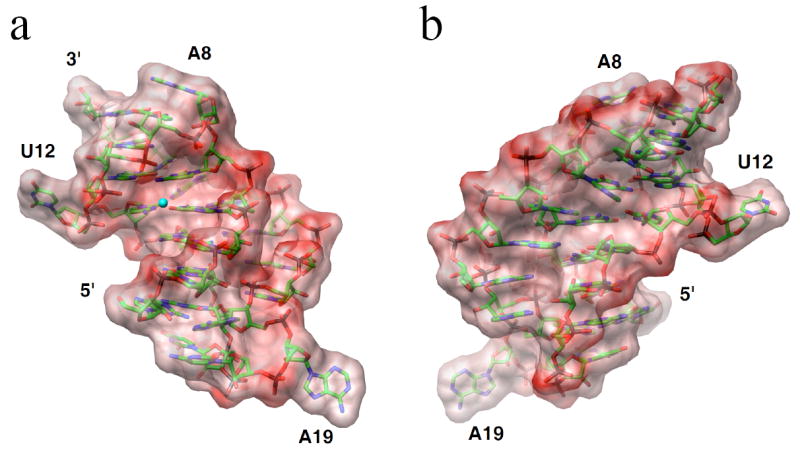

Compared to the wt-pkRNA from PLRV, the crystallized double mutant enhances frameshifting twofold (6). It is unlikely that this change is a consequence of an altered thermodynamic stability of the pseudoknot, although higher stability is expected to positively affect frameshifting efficiency. Comparison of the deletion mutants ΔU12 and ΔA18-A21 nicely illustrates this point (Table 3). Their stabilities are very similar, but the former is basically incapable of stimulating frameshifting whereas the latter is as efficient as wt. The crystallized pseudoknot mutant is more stable than wt, but based on the above observation the >200% increase in efficiency is unlikely to be the result of the higher stability alone. Computation of the electrostatic surface potential of the PLRV pseudoknot demonstrates that the RNA is predominantly negatively polarized and that the aforementioned residues form more or less neutral patches (Fig. 4). For corresponding images of the BWYV pseudoknot RNA see Figure S1 in the Supplementary Materials on-line. Thus, both in terms of their electrostatic properties and their locations on the surface, rendering them available for potential hydrogen bonding and stacking interactions with ribosomal proteins, the linker region, A8 and U12 and appear poised to play an important role in frameshifting.

Table 3.

Thermodynamic Stabilitiesa of wt PLRV pk-RNA and Selected Mutants

| Sequence | Efficiency [%]a | Tm [°C] | |

|---|---|---|---|

| wta | 8.8 | 50 |

|

| C17U/A18C | 18.7 (2.12) | 62 | |

| ΔU12 | 0.7 (0.08) | 42 | |

| ΔA18-A21 | 8.6 (0.98) | 38 |

The graph on the right depicts molar ellipticities vs. temperature

Efficiency relative to wt shown in parentheses

Sequence 5’-GCG GCA CCG UCC GCC AAA ACA AAC GG (U12 and C17-A21 underlined)

FIGURE 4.

Electrostatic surface potentials of the PLRV pseudoknot RNA. a, the PLRV pseudoknot viewed into the major grooves of stem 1 and stem 2 with loop 2 on the right. b, rotated by 180° around the vertical relative to panel a, and viewed into the continuous minor groove formed by stems 1 and 2. The potentials were calculated with the program GRASP (26) and are displayed in the energy range between −50 to +50 kBT/e. Single negative charges were used for all nucleotides with the exception of C7 that was assumed to be neutral. Red regions are negatively polarized and a Mg2+ ion coordinated near the interface between stem 1 and stem 2 is depicted as a small cyan sphere.

Construction of a Minimal Frameshifting Motif

Changes in the sequence of the linker crucially affect the extent of frameshifting. Thus, the crystallized mutant increases frameshifting by >200% and the C17G/A18C double mutant also shows increased frameshifting relative to wt (60%) (6). Interestingly, a G19[UC19a] mutation/insertion in the case of BWYV pkRNA triggered a 300% increase in frameshifting (8). If one considers C17 in the PLRV pkRNA (U17 in the mutant; Fig. 1a) as part a hypothetical G:C base pair (G18:C3 in BWYV pkRNA), then both linkers in the highest ‘frameshifters’ (the C18A19 and U19C19a mutants for PLRV and BWYV, respectively) are made up of two nucleotides. However, deletions in the linker and loop 2 region immediately adjacent to it (residues 20 and 21) in the PLRV and BWYV pkRNAs trigger vastly different effects in the two systems. Deletion of G19 in the case of BWYV alone reduces the frameshifting efficiency by 50% (8). Deletion of a second residue (i.e. A20) can be predicted to disrupt the pseudoknot based on the structure. Thus, G18 cannot possibly be linked directly to A21 without disrupting the C3:G18 pair and severely destabilizing stem 1. Conversely, up to four nucleotides of the linker and adjacent loop 2 (see boxed residues in Fig. 1a) can be deleted in the PLRV pkRNA without substantially altering frameshifting relative to the wt pseudoknot (Table 3) (6). Irrespective of whether residue 17 is C (wt), U (our mutant), G or A, the frameshifting efficiency resembles that of wt (8.8%) and varies between 8 and 12% (6).

Inspection of the PLRV pkRNA crystal structure shows that deletion of residues C18, A19, A20 and A21 (Fig. 1a) results in a gap between residues C16 and C22 that can be readily bridged by U17 (Fig. 5). The resulting pseudoknot molecule is composed of only 22 nucleotides and can be viewed as a minimal motif that is capable of stimulating ribosomal frameshifting. Its stems are four and three base pairs long (stem 1 and 2, respectively) and are connected by two- (loop 1) and four-nucleotide loops (loop 2), whereby the linker between stem 1 and loop 2 involves just a single nucleotide.

FIGURE 5.

Model of a minimal frameshifting-pseudoknot motif. a, three-dimensional model of a 22-nucleotide pkRNA that triggers frameshifting comparable in extent to that observed with PLRV wt-pkRNA. To build the model, nucleotides C18, A19, A20 and A21 were excised from the crystal structure of PLRV pkRNA, the 3’-OH of U17 was connected to the 5’-PO3- of C22 by manually repositioning the linker nucleotide U17 (gray), and the resulting structure was energy-minimized. b, the trinucleotide C16-U17-C22 (color code for carbon atoms matches that in panel a superpositioned on the linker-loop 2 motif observed in the crystal structure of PLRV pkRNA (green).

Mechanism of Frameshifting

The combined structural and functional data for the two luteoviral pkRNAs support the notion that in addition to tertiary structural elements that stabilize the mRNA fold and allow it to resist unraveling by the ribosome (the quadruple base interaction involving C7 and the minor groove triplex), unpaired residues on the surface can modulate frameshifting to a significant extent. Thus, nucleotides of the stem 1-loop 2 linker play an important role in enhancing or reducing frameshifting efficiency relative to wt. This particular way to modulate efficiency should be considered independent of the geometry of the remainder of the pseudoknot scaffold, i.e. the geometry at the stem 1-stem 2 junction, that is virtually identical in the crystal structures of the BWYV and PLRV pkRNAs. It is tempting to conclude that such residues can directly interact with ribosomal proteins at the downstream mRNA entry site, thereby making it more difficult for the ribosome to unwind the message prior to its entering the mRNA tunnel (Fig. 6). It is noteworthy that the linker region comprising residues U17, C18 and A19 likely constitutes the portion of the pseudoknot that reaches the ribosomal entry tunnel first.

FIGURE 6.

Stereo diagram depicting a model of an early stage of pseudoknot-stimulated ribosomal frameshifting, with the ribosome pausing and the PLRV pkRNA wedged in the funnel formed by the S3, S4 and S5 proteins. Coordinates of the Cα chains for the S3, S4 and S5 proteins were taken from the structure of the T. thermophilus 30S ribosomal subunit (23). The color codes for individual regions of the pseudoknot are identical to those in Fig. 1b and selected residues are labeled. The path of the mRNA through the ribosome is indicated by a black ribbon, and the positions of A and P site codons are highlighted in orange. Six nucleotides link the 3’-terminal nucleotide of the A-site codon to the 5’-terminal G of the pseudoknot when the slippery sequence occupies the A and P sites. The model illustrates that the linker between stem 1 and loop 2 (gray backbone ribbon in the pkRNA; residues C17-A19) is likely one of the first features of the pseudoknot that the ribosome encounters. Similarly, other looped-out residues, such as U12 in the central region and A8 that caps the RNA pseudoknot at the opposite end are candidates for interactions with ribosomal proteins. The reader is referred to Fig. 7 in ref. (10) for a diagram that depicts arginine and lysine side chains from the S3, S4 and S5 proteins protruding into the downstream entry tunnel. These proteins are believed to act as the processivity clamp for the helicase function of ribosomes. The above basic side chains allow the ribosome to grip folded mRNAs, thereby disrupting secondary structure upon translocation. Rather than the obvious interactions between arginines from S3, S4 or S5 and phosphate groups from folded mRNAs, pausing of the ribosome upon encountering a pseudoknot may involve formation of specific contacts between such side chains and looped-out pkRNA residues.

CONCLUSIONS

Structural work on frameshifting pkRNAs in the absence of the ribosome cannot provide further insights into the detailed mechanism of programmed -1 type shifts in the reading frame. However, crystal structures of complexes between messenger RNA and the 70S (22) ribosome or the 30S ribosomal subunit (23) may shed light on different stages of frameshifting and the detailed interactions between RNA pseudoknot and ribosome as the former lodges at the downstream entry site. A potential impediment to such an approach is constituted by the fact that luteoviral systems such as BWYV and PLRV for which we now have structural information at high resolution (ref. (5) and this paper) trigger frameshifting in eukaryotic hosts. By contrast, crystallographic studies of complete ribosomes (22,24) and the small subunit (23) have so far been limited to prokaryotic organisms. Therefore, it will be necessary to demonstrate frameshifting on mRNAs with BWYV or PLRV pseudoknots by prokaryotic ribosomes before embarking on a crystallographic investigation of ribosome-mRNA complexes. Interestingly, the pseudoknot contained in mouse mammary tumor viral mRNA was shown to provoke E. coli ribosomes to shift frame in the same manner as their eukaryotic counterparts (25).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Queta Boese, Dharmacon Inc. for helpful discussions.

Footnotes

Supported by NIH Grant GM47299 (M.E., A.R.). Use of the Advanced Photon Source was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Basic Energy Sciences, Office of Science, under Contract No. W-31-109-Eng-38. The DuPont-Northwestern-Dow Collaborative Access Team (DND-CAT) Synchrotron Research Center at the Advanced Photon Source (Sector 5) is supported by E. I. DuPont de Nemours & Co., The Dow Chemical Company, the National Science Foundation, and the State of Illinois.

Final coordinates and structure factors have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, PDB ID 2A43 (http://www.rcsb.org).

Abbreviations: PLRV, potato leaf roll virus; BWYV, beet western yellow virus, pk, pseudoknot.

References

- 1.Doudna JA, Lorsch JR. Ribozyme catalysis: not different, just worse. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2005;12:395–402. doi: 10.1038/nsmb932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Winkler WC, Nahvi A, Roth A, Collins JA, Breaker RR. Control of gene expression by a natural metabolite-responsive ribozyme. Nature. 2004;428:281–286. doi: 10.1038/nature02362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pleij CWA, Bosch L. RNA pseudoknots: structure, detection and prediction. Methods Enzymol. 1989;180:289–303. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(89)80107-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gesteland RF, Atkins JF. Recoding: dynamic reprogramming of translation. Annu Rev Biochem. 1996;65:741–768. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.65.070196.003521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Giedroc DP, Theimer CA, Nixon PL. Structure, stability and function of RNA pseudoknots involved in stimulating ribosomal frameshifting. J Mol Biol. 2000;298:167–169. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim Y-G, Maas S, Wang SC, Rich A. Mutational study reveals that tertiary interactions are conserved in ribosomal frameshifting pseudoknots of two luteoviruses. RNA. 2000;6:1157–1165. doi: 10.1017/s1355838200000510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Su L, Chen L, Egli M, Berger JM, Rich A. Minor groove RNA triplex in the crystal structure of a ribosomal frameshifting viral pseudoknot. Nat Struct Biol. 1999;6:285–292. doi: 10.1038/6722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim Y-G, Su L, Maas S, O’Neill A, Rich A. Specific mutations in a viral RNA pseudoknot drastically change ribosomal frameshifting efficiency. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:14232–14239. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.25.14234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Egli M, Sarkhel S, Minasov G, Rich A. Structure and function of the ribosomal frameshifting pseudoknot RNA from beet western yellow virus. Helv Chim Acta. 2003;86:1709–1727. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Takyar S, Hickerson RP, Noller HF. mRNA helicase activity of the ribosome. Cell. 2005;120:49–58. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.11.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Howard MT, Gesteland RF, Atkins JF. Efficient stimulation of site-specific ribosome frameshifting by antisense oligonucleotides. RNA. 2004;10:1653–1661. doi: 10.1261/rna.7810204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kabsch W. Automatic processing of rotation diffraction data from crystals of initially unknown symmetry and cell constants. J Appl Cryst. 1993;26:795–800. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vagin A, Teplyakov A. MOLREP: an automated program for molecular replacement. J Appl Cryst. 1997;30:1022–1025. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brünger AT, Adams PD, Clore GM, DeLano WL, Gros P, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Jiang JS, Kuszewski J, Nilges M, Pannu NS, Read RJ, Rice LM, Simonson T, Warren GL. Crystallography & NMR System: A new software suite for macromolecular structure determination. Acta Cryst. 1998;D 54:905–921. doi: 10.1107/s0907444998003254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cambillau C, Roussel A. TURBO FRODO, Version OpenGL.1. Université Aix-Marseille II; Marseille, France: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sheldrick GM, Schneider TR. SHELXL: high-resolution refinement. Meth Enzymol. 1997;277:319–343. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brünger AT. Free R value: a novel statistical quantity for assessing the accuracy of crystal structures. Nature. 1992;355:472–475. doi: 10.1038/355472a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Egli M, Minasov G, Su L, Rich A. Metal ions and flexibility in a viral RNA pseudoknot at atomic resolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:4302–4307. doi: 10.1073/pnas.062055599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gluick TC, Wills NM, Gesteland RF, Draper DE. Folding of an mRNA pseudoknot required for stop codon readthrough: effects of mono- and divalent ions on stability. Biochemistry. 1997;36:16173–16186. doi: 10.1021/bi971362v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nixon PL, Giedroc DP. Energetics of a strongly pH dependent RNA tertiary structure in a frameshifting pseudoknot. J Mol Biol. 2000;296:659–671. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sarkhel S, Rich A, Egli M. Water-nucleobase “stacking” H-π and lone pair-π interactions in the atomic resolution crystal structure of an RNA pseudoknot. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:8998–8999. doi: 10.1021/ja0357801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yusupova GZ, Yusupov MM, Cate JHD, Noller HF. The path of messenger RNA through the ribosome. Cell. 2001;106:233–241. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00435-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wimberly BT, Brodersen DE, Clemons WM, Jr, Morgan-Warren RJ, Carter AP, Vonrhein C, Hartsch T, Ramakrishnan V. Structure of the 30S ribosomal subunit. Nature. 2000;407:327–339. doi: 10.1038/35030006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vila-Sanjurjo A, Ridgeway WK, Seymaner V, Zhang W, Santoso S, Yu K, Doudna Cate JH. X-ray crystal structures of the WT and a hyper-accurate ribosome from Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:8682–8687. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1133380100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weiss RB, Dunn DM, Shuh M, Atkins JF, Gesteland RF. E. coli ribosomes re-phase on retroviral frameshift signals at rates ranging from 2 to 50 percent. The New Biologist. 1989;1:159–169. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nicholls A, Bharadwaj R, Honig B. GRASP: graphical representation and analysis of surface properties. Biophys J. 1993;64:166–170. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.