Abstract

Hypoxia is a mounting problem affecting the world's coastal waters, with severe consequences for marine life, including death and catastrophic changes. Hypoxia is forecast to increase owing to the combined effects of the continued spread of coastal eutrophication and global warming. A broad comparative analysis across a range of contrasting marine benthic organisms showed that hypoxia thresholds vary greatly across marine benthic organisms and that the conventional definition of 2 mg O2/liter to designate waters as hypoxic is below the empirical sublethal and lethal O2 thresholds for half of the species tested. These results imply that the number and area of coastal ecosystems affected by hypoxia and the future extent of hypoxia impacts on marine life have been generally underestimated.

Keywords: benthic community, oxygen, coastal ecosystems, eutrophication, impacts

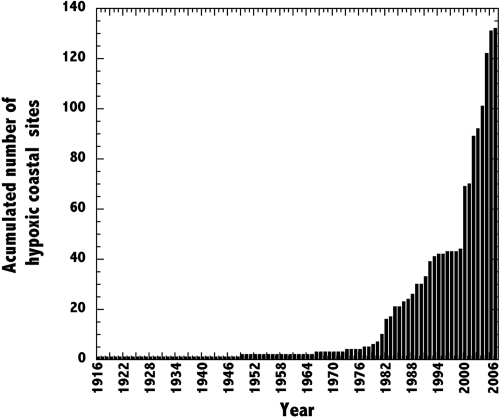

Dissolved oxygen in coastal waters has changed drastically over the past decades, arguably more so than any other ecologically important variable (1, 2), leading to the widespread occurrence of hypoxia. An assessment of the literature shows that the number of coastal sites where hypoxia has been reported has increased with an exponential growth rate of 5.54% year−1 over time [Fig. 1 and supporting information (SI) Table S1]. Although this growth rate can be partially attributed to an increased observational effort, increasing the number of costal ecosystems monitored and the likelihood of detecting hypoxia therein, this growth also reflects an increase in the prevalence of hypoxia in different types of coastal ecosystems. Multiple reports from careful monitoring time series provide evidence for an unambiguous increase in the number of hypoxic zones and their extension, severity, and duration (3–6). This growth is expected to continue because the prevalence of hypoxia is forecast to increase further owing to the combined effects of eutrophication, leading to the excessive production of organic matter that increases the oxygen demand of coastal ecosystems (7), and the increase in temperature caused by climate change, which enhances the respiratory oxygen demand of the organisms (8), reduces oxygen solubility (9), and reduces the ventilation of coastal waters by affecting stratification patterns (10).

Fig. 1.

Accumulated number through time of coastal sites where hypoxia has been reported. Exponential growth rate = 5.54% ± 0.23% year−1 (R2 = 0.86, P ≤ 0.01).

Coastal hypoxia is, thus, emerging as a major threat to coastal ecosystems globally. Hypoxia has been shown to trigger mortality events, resulting in a depletion of metazoans in the ecosystems, resulting in so-called “dead zones” devoid of fisheries resources, such as fish, shrimp, and crabs (11, 12). Hypoxia leads to major loss in biodiversity and impacts the surviving organisms through sublethal stresses, such as reduced growth and reproduction, physiologic stress, forced migration, reduction of suitable habitat, increased vulnerability to predation, and disruption of life cycles (7, 11). Benthic organisms are particularly vulnerable to coastal hypoxia because they live farthest from contact with atmospheric oxygen supply and because coastal sediments tend to be depleted in oxygen relative to the overlying water column.

Assessing the thresholds of oxygen at which lethal and sublethal impacts occur is critical to establish the vulnerability of marine organisms to hypoxia and to set management targets to avoid catastrophic mortality. Hundreds of experiments to determine thresholds of hypoxia for a range of benthic organisms have been conducted. However, the oxygen thresholds for hypoxia proposed in the literature (1, 12, 13) are based on limited observations of impacts on organisms (7), and a thorough empirical assessment of the available experimental evidence is still pending. Whereas the thresholds of hypoxia proposed in the literature range broadly from 0.28 mg O2/liter (14) to 4 mg O2/liter (15), most reports (55%) refer to a value of 2 mg O2/l or lower (mean ± SE of thresholds proposed in the literature: 2.31 ± 0.10 mg O2/liter; Table S2) used in most conventional applications (16). This thresholds refers to the oxygen level for fisheries collapse (12), but there is ample experimental evidence that a 2-mg O2/liter threshold may be inadequate to describe the onset of hypoxia impacts for many organisms, which experience hypoxia impacts at higher oxygen concentrations (e.g., 17). Moreover, the diversity of behavioral and physiologic adaptations to hypoxia (18) suggests that different taxa are likely to exhibit different vulnerability to hypoxia and may have, therefore, different oxygen thresholds (19), a possibility that is not addressed by the conventional oxygen thresholds in use (cf. Table S2).

The goal of this article is to examine the variability in oxygen thresholds for hypoxia across benthic organisms and to test for the existence of consistent differences among taxa. We do so on the basis of a comparative analysis of experimentally derived oxygen thresholds for lethal and sublethal responses to hypoxia of benthic organisms. We aim to improve our understanding of the levels of hypoxia that cause significant impacts on marine benthic communities. This understanding will offer a more rigorous basis on which to establish critical thresholds to preserve fishery resources and to effectively conserve coastal biodiversity as hypoxia continues to rise as a threat to coastal ecosystems.

Results

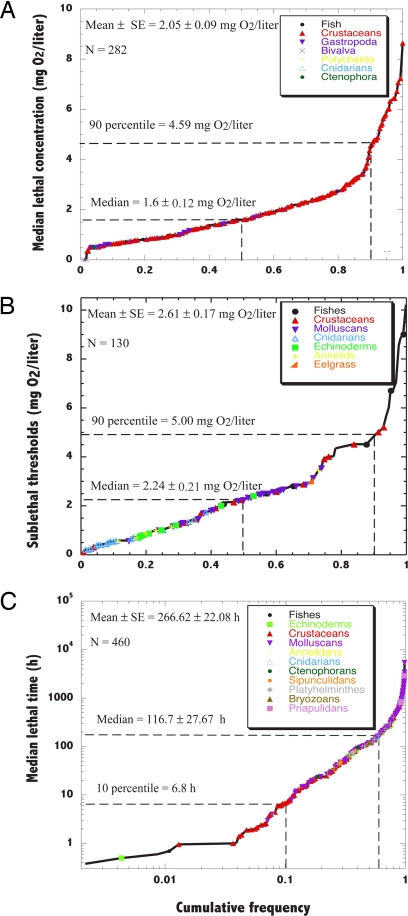

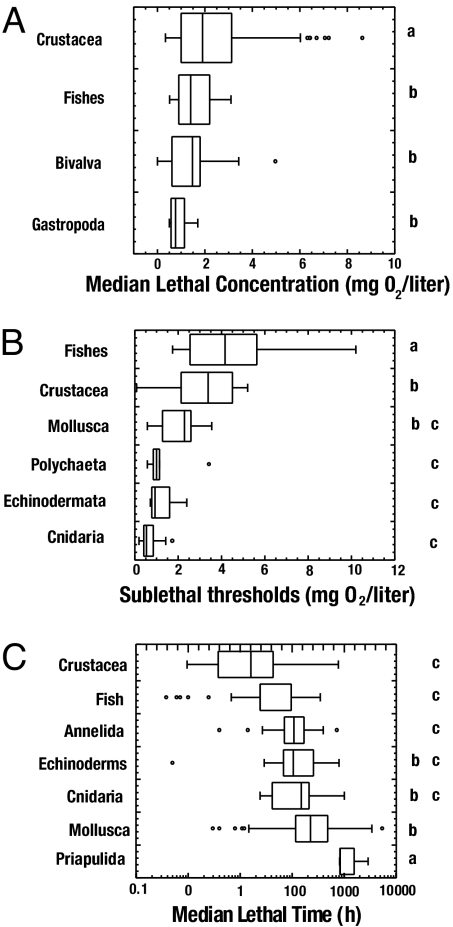

We found a total of 872 published experiments reporting oxygen thresholds and/or lethal times for a total of 206 species spanning the full taxonomic range of benthic metazoans. The examination of thresholds for hypoxia derived experimentally revealed the existence of a broad range of variability, with median lethal and sublethal oxygen thresholds and LT50s after exposure to hypoxia ranging over an order of magnitude across experiments (Fig. 2 and Table S3, Table S4, and Table S5). The cumulative distributions representing the distribution of oxygen thresholds present a change in slope near the 90th percentile of the distribution and the 10th percentile of the LT50 (Fig. 2), showing the existence of a small proportion (10%) of experiments yielding extreme sensitivity to hypoxia, reflected in particularly high oxygen thresholds for hypoxic responses (≥5 mg O2/liter) and short (≤2 h) lethal times. All relevant thresholds varied significantly across taxa (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

Cumulative distribution of (A) LC50 (mg O2/liter), (B) SCL50 (mg O2/liter), and (C) LT50 (h) for marine benthic communities (Table S3, Table S4, and Table S5). The mean ± SE, median ± SE, 90th percentile (10th percentile for LT50), and number of experiments are indicated.

Fig. 3.

Box plot showing the distributions of oxygen thresholds among taxa for (A) LC50 (mg O2/liter), (B) SCL50 (mg O2/liter), and (C) LT50 (h). The letters indicate the results of the Tukey HSD test, whereby the property examined did not differ significantly for taxa with the same letter.

Median Lethal Concentration.

Median lethal oxygen concentrations (LC50) ranged from 8.6 mg O2/liter for the first larval zoea stage of the crustacean Cancer irroratus (17), the most sensitive species tested, to persistent resistance to complete anoxia of the oyster Crassostrea virginica at temperatures of 20°C (20). The larval stages of C. irroratus (17) were found to be extremely vulnerable to hypoxia, with thresholds exceeding the 95th percentile of the distribution of LC50 values across crustaceans. The mean LC50 (±SE) for all organisms tested was found to be 2.05 ± 0.09 mg O2/liter, whereas the median was 1.60 ± 0.12 mg O2/liter, and the coefficient of variation was 78% across experiments, indicative of considerable variability in these thresholds across organisms (Fig. 2A). Ninety percent of the experiments showed LC50 values below 4.59 mg O2/liter (Fig. 2A).

Some of the variability in median lethal O2 thresholds was attributable to differences across groups (ANOVA, F = 10.03, P < 0.001; Fig. 3A), because crustaceans showed O2 thresholds significantly higher than for other taxa (Tukey post hoc honestly significant difference [HSD] test, P ≤ 0.05; Fig. 3A). Gastropods showed the lowest median lethal oxygen thresholds, although it did not differ significantly (Tukey post hoc HSD test, P ≥ 0.05; Fig. 3A) from that of fish and bivalves. We also tested whether the extent of mobility of the organisms accounted for variability in the experimentally derived median lethal O2 thresholds. Indeed, we found that the median lethal O2 thresholds differed significantly with the extent of mobility of the organisms tested (ANOVA, F = 11.29, P < 0.001). Two-way ANOVA showed that the degree of mobility (F test, P ≤ 0.001), which accounted for 20% of the variance in median lethal concentrations among experiments, was superior to differences among taxa (F test, P ≥ 0.05) in accounting for variability across experiments.

Median Sublethal Concentration.

Median sublethal concentration (SLC50) thresholds ranged from 10.2 mg O2/liter for cod, Gadus morhua, which raises its ventilatory water flow below this concentration (21, 22), to 0.085 mg O2/liter for the burrowing shrimp Calocaris macandreae (Thalassinidea), which switches from aerobic to anaerobic metabolism below this threshold (23). The mean ± SE SLC50 was 2.61 ± 0.17 mg O2/liter, the median SLC50 was 2.24 ± 0.21 mg O2/liter, and the coefficient of variation was 76%, showing important variability in median sublethal thresholds among experiments (Fig. 2B). Ninety percent of the experiments conducted reported median sublethal oxygen concentrations below 5.00 mg O2/liter (Fig. 2B).

As for the median lethal O2 thresholds, some of the variability in median sublethal O2 thresholds was attributable to differences among taxa, which was stronger for sublethal than for lethal responses (ANOVA, F = 21.75, P < 0.001; Fig. 3B). Fish had significantly higher oxygen thresholds for sublethal responses (Tukey post hoc HSD test, P < 0.05; Fig. 3B), which typically involved avoidance of hypoxic waters, depressed activity, shift to oxygen-dependent metabolism, or increased ventilatory water flow. Crustaceans also presented significantly higher oxygen thresholds for sublethal responses than polychaetes, echinoderms, and cnidarians (Tukey post hoc HSD test, P < 0.05; Fig. 3B), which typically involved avoidance of hypoxic waters, reduced growth, reduced predation rates, lethargy, or decreased activity, among others. Fish and crustaceans, which showed the highest median sublethal O2 thresholds, are also the taxa with the highest mobility, which confers them some capacity to avoid hypoxic waters. Indeed, two-way ANOVA showed that both differences among taxa and the extent of mobility among organisms were significant (F test, P ≤ 0.001), accounting for 52% of the variance in median sublethal concentrations among experiments (F = 11.6, P ≤ 0.001).

Median Lethal Time.

The median lethal time (LT50) upon exposure to acute hypoxia ranged greatly across organisms tested (Fig. 2C), from only 23 min for the flounder Platichthys flesus (19, 24), to more than 32 weeks for the bivalve Astarte borealis at temperatures below 20°C (25). The mean (± SE) LT50 was 267.9 ± 22.0 h, the median was 116.7 ± 27.67 h, and the coefficient of variation was 178% across experiments, indicative of considerable variability in these thresholds across organisms (Fig. 2C). Ten percent of the organisms showed LT50 upon exposure to acute hypoxia of less than 6.8 h (Fig. 2C). There were significant differences in LT50 under hypoxia among taxa (ANOVA, F = 11.12, P < 0.001; Fig. 3C). In particular, Priapulida, the most tolerant group, had significantly longer LT50 under hypoxia than other taxonomic groups, and molluscs, the second most tolerant group, also showed significantly longer LT50 under hypoxia than annelids, fish, and crustaceans, which were the most sensitive groups (Fig. 3C). Sessile organisms also had longer LT50 than mobile organisms did (F test, P ≤ 0.01). However, two-way ANOVA showed that differences among taxa (F test, P ≤ 0.001), which explained 17% of the variance in LT50, were superior to differences in mobility (F test, P ≥ 0.05), to account for variability among experiments.

We also found significant ontogenic shifts in survival time, with early stages having survival times, on average, 64% ± 7% (H0 linear regression slope = 1, t test, P < 0.05) of those of more developed stages for any one species, whereas similar effects were not found for lethal or sublethal concentrations.

Discussion

The results presented here provide evidence of the broad, order-of-magnitude variability in the thresholds of oxygen concentrations for hypoxia among benthic marine organisms, which cannot be adequately captured by a single, universal threshold. This variability partially derived from significant differences in oxygen thresholds across taxa. The most sensitive organisms were crustaceans, which showed the highest LC50 and the shortest LT50, whereas fish exhibit sublethal responses at the highest O2 concentration (Fig. 3). On the other hand, molluscs, with the lowest LC50, are the organisms most tolerant to hypoxia, together with cnidarians, which showed the lowest LC50 for sublethal threshold, and priapulids, which showed the longest LT50.

The differences in oxygen thresholds for hypoxia across taxa probably reflect the broad differences in adaptations to cope with low oxygen conditions among benthic organisms, which span a broad range of behavioral and metabolic changes. Mobile organisms have the capacity to avoid hypoxic waters and thus tend to show comparably high oxygen thresholds. Benthic fish have been reported to move to near-surface waters to breathe when bottom waters become hypoxic (26), and crustaceans move to shallower areas (27), where these organisms are more vulnerable to predation. Yet fast-moving organisms (e.g., fish) do not necessarily show higher lethal thresholds than those with more restrictive mobility (e.g., crustaceans), pointing to differences among taxa independent of their relative mobility.

Many benthic organisms (polychaetes, annelids, crustaceans, bivalves, priapulids, and anemones) leave their burrows or tubes to move to the sediment surface or reduce their burial depth (28, 29) in the presence of hypoxia. Some bivalves stretch their siphons upward into the water column to reach waters with higher oxygen concentrations (30). Some echinoderms stand immobile on their arm tips with the central disk elevated to avoid the hypoxic bottom water (31), and some gastropods climb structures to reach waters with higher oxygen concentration. Metabolic adaptations to cope with hypoxia include depression of activity in the presence of hypoxia, as reported for echinoderms (32); reduced feeding activity (e.g., some crustaceans, molluscs, and polychaetes; refs. 33–35); reduced metabolic rates (e.g., cnidarians; ref. 36) and heartbeat rate (some crustaceans; ref. 37); and shift to anaerobic metabolism over time scales of hours to days, an adaptation widespread among bivalves (38, 39), polychaetes (40), oligochaetes (41), echinoderms (42), and the mud-shrimp Calocaris macandreae (23), among others.

The broad variability in oxygen thresholds shown here is in contrast with the widespread use of uniform thresholds for hypoxia in the literature (Table S2). The vast majority of studies and reports continue to use the 2-mg O2/liter convention, originally derived as the oxygen threshold for fisheries collapse (12). A total of 43% and 21.5% of the published reports used the 2-mg O2/liter and the 2-ml/liter (i.e., 2.85 mg O2/liter) threshold, respectively, and a single study (15) used a threshold of 4 mg O2/liter (Table S2). A seminal review by Gray et al. (19), which included experimental studies reporting mortality thresholds well above 2 mg O2/liter, concluded that “mortality occurs where concentrations are below 2.0 to 0.5 mg O2/liter”; and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency recommends a threshold of 2.3 mg O2/liter for juvenile and adult aquatic organism survival (43). In a recent review, Díaz and Rosenberg (54) state that “hypoxia occurs when DO falls below 2 ml of O2/liter … culminating in mass mortality when DO declines below 0.5 ml of O2/liter.” The results presented here show that the conventionally accepted level of 2 mg O2/liter falls well below the oxygen thresholds for the more sensitive taxa.

Whereas the conventional 2 mg O2/liter may signal levels of hypoxia at which fisheries collapses, the results presented here show that it is inadequate as a threshold to conserve coastal biodiversity, because significant mortality would have already been experienced by many species. The frequency distribution of thresholds of hypoxia compiled here (Fig. 2) shows that 61.43% and 42.85% of the species tested here experience substantial (≥50% of the population) mortality and sublethal responses, respectively, at oxygen thresholds above 2 mg O2/liter. In particular, most fish and crustaceans would be lost before the oxygen content of the waters reaches the threshold of 2 mg O2/liter for these waters to be considered hypoxic by conventional criteria. Indeed, fish and crustaceans are main fishery resources, so that the 2-mg O2/liter threshold may be too low not only to effectively conserve biodiversity but to conserve fisheries resources as well.

Currently used thresholds of hypoxia are not conservative enough to avoid widespread mortality losses and need be critically revised. The frequency distribution of thresholds presented here provides a basis to allow the evaluation of the risk of biodiversity losses with decreasing oxygen concentration, thereby considering a range of thresholds for hypoxia, rather than a mean value that does not capture the order-of-magnitude variability across organisms. For instance, waters with oxygen concentrations below 4.6 mg O2/liter, the 90th percentile of the distribution of mean lethal concentrations, would be expected to maintain the population for most, except the 10% most sensitive, species. This oxygen level could thus be considered as a precautionary limit to avoid catastrophic mortality events, except for the most sensitive crab species, and effectively conserve marine biodiversity. Indeed, it is possible to carry this analysis further to consider taxon-specific thresholds of hypoxia, at the 90th percentile of the distribution of LC50 for the various taxa (Table 1). Taxon-specific approaches help accommodate some of the variability in experimental thresholds and allow the definition of more specific conservation targets in legislative, managerial, and restoration plans.

Table 1.

Distribution of thresholds of hypoxia for different groups of benthic organisms

| Organisms | LC50, mg O2/liter | SLC50, mg O2/liter | LT50, h |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fish | |||

| Mean ± SE | 1.54 ± 0.07 | 4.41 ± 0.39 | 59.9 ± 12.3 |

| 90th percentile | 2.51 | 8.09 | 0.9 |

| n | 77 | 34 | 39 |

| Crustaceans | |||

| Mean ± SE | 2.45 ± 0.14 | 3.21 ± 0.28 | 55.5 ± 12.4 |

| 90th percentile | 5.72 | 5.0 | 1.0 |

| n | 168 | 30 | 102 |

| Gastropods | |||

| Mean ± SE | 0.89 ± 0.11 | ||

| 90th percentile | 1.62 | ||

| n | 12 | ||

| Bivalves | 1.42 ± 0.14 | ||

| Mean ± SE | |||

| 90th percentile | 3.43 | ||

| n | 19 | ||

| Molluscs | |||

| Mean ± SE | 1.99 ± 0.16 | 412.9 ± 37.3 | |

| 90th percentile | 2.83 | 55.4 | |

| n | 28 | 239 | |

| Annelids | |||

| Mean ± SE | 1.20 ± 0.25 | 132.2 ± 18.7 | |

| 90th percentile | 1.37 | 37.8 | |

| n | 10 | 43 | |

| Echinoderms | |||

| Mean ± SE | 1.22 ± 0.22 | 201.1 ± 44.8 | |

| 90th percentile | 2.12 | 33.6 | |

| n | 8 | 23 | |

| Cnidarians | |||

| Mean ± SE | 0.69 ± 0.11 | 232.5 ± 114.4 | |

| 90th percentile | 1.43 | 24 | |

| n | 19 | 8 | |

| Priapulids | |||

| Mean ± SE | 1512.0 ± 684.0 | ||

| 90th percentile | 820.8 | ||

| n | 3 | ||

Shown are mean ± SE, 90th percentile (10th percentile for lethal times), and number of observations of LC50, SLC50, and LT50 for the various groups.

There are important limitations to extrapolate from experimentally determined thresholds in controlled, laboratory conditions to the field (1, 44–46), derived from the facts that (i) the oxygen concentrations in the experiments are held constant, whereas they would show variations in nature due to diel cycles in net community production, including the contribution of the organisms tested themselves, and mixing; (ii) hypoxia often occurs in concert with other stresses in nature, and although some experiments addressed thresholds of hypoxia in the presence of additional stressors (e.g., high temperature, sulfide), most experiments used reduced oxygen as the single treatment variable; and (iii) the experimental evaluation of the role of mobility in avoiding hypoxia is cumbersome and was directly addressed in only two of the experimental studies reviewed here (47, 48). The alternative approach to estimate oxygen thresholds for mortality of the various species of benthic organisms in the field is, however, elusive, because this would require an accurate estimate of their population sizes and because, as indicated above, oxygen levels fluctuate in ecosystems, rendering it difficult to assign observed mortalities to a specific oxygen value. Indeed, the difficulties to resolve oxygen thresholds in the field explain why the bulk of the studies conducted to this end, synthesized here (Table S3 and Table S5), have been conducted under laboratory conditions. These considerations apply not only to oxygen thresholds but to all experiments in toxicology, which cannot be appropriately controlled in the field. Most of the processes indicated above would lead, however, to the laboratory-determined oxygen thresholds being below those in the field, except in the case of avoidance for mobile organisms (which is, however, addressed as a sublethal response in laboratory experiments). Hence, the results derived from laboratory experiments should be considered conservative.

Consideration of the different thresholds of hypoxia among taxa derived here (Fig. 3 and Table 1) predicts that the sequence of losses of benthic fauna during hypoxic events should be initiated by the loss of fish, followed by crustaceans, then worms, echinoderms, and molluscs as oxygen declines. This prediction is consistent with the observed sequence of losses of benthic fauna during hypoxic events, as reported in the Danish fjords (30) and the Baltic Sea (49). The agreement between the sequences of losses of various taxa with hypoxia predicted from laboratory experiments and those observed in coastal areas impacted by hypoxia provides additional confidence in the relevance of laboratory experiments. The pattern of recolonization of benthic fauna lost to hypoxia upon subsequent improvement of the oxygen conditions differs, however, from the pattern of loss, because recolonization patterns, which are initiated by polychaetes (50, 51), are determined by life-history and dispersal properties of the organisms and not their resistance to hypoxia.

The conclusion that oxygen depletion induces significant mortality at critical oxygen thresholds exceeding by 2.3 times the 2-mg O2/liter threshold generally used in the literature implies that the present inventory of the number and extent of hypoxic areas in the coastal zone, which uses the occurrence of oxygen levels ≤2 mg O2/liter (Fig. 1), represents an underestimate of the coastal areas experiencing mortality of benthic organisms attributable to hypoxia. Hence, benthic organisms may be suffering substantial mortality in areas not presently designated as hypoxic. The conventional 2-mg O2/liter limit serves to separate “dead zones,” depleted of most of the commercially harvested species, from waters supporting significant benthic animal communities. However, it fails to reflect the oxygen threshold at which these communities experience hypoxia-derived mortality. The pace of growth of hypoxia as a major threat to coastal biodiversity and associated living resources may be, therefore, greater than hitherto considered. Moreover, there is ample evidence that the oxygen requirements of marine animals are even higher in the presence of concurrent stresses, such as high temperature (52) or sulfide concentrations (53), suggesting that areas under stress are particularly prone to experience hypoxia-derived catastrophic mortality. These interactions are not considered in present assessments and classifications but are likely to play a more prominent role in the future as global warming and other mounting stresses in the coastal ocean increase the sensitivity of benthic organisms to oxygen depletion. Indeed, a recent assessment concluded that the area of hypoxia (defined as ≤2 mg O2/liter) in Danish coastal waters, one of the countries most severely affected by this problem, will more than double under the projected temperature increase over the 21st century (6), an estimate that needs be revised upwards in light of the higher oxygen thresholds for hypoxia proposed here.

The analysis presented here demonstrates that hypoxia impacts occur at a broad range of oxygen concentrations, including oxygen concentrations well above the oxygen thresholds generally used to diagnose hypoxia at present. The vulnerability of coastal ecosystems to hypoxia is, thus, greater than currently recognized, with fish and crustaceans being the most vulnerable faunal components. The number and extent of the coastal zones affected by hypoxia is, thus, likely to be greater than hitherto realized, and the prospects for future expansion of these areas more disturbing than currently forecasted. Coastal hypoxia is, thus, emerging as a major threat to coastal ecosystems globally. The revised thresholds of hypoxia provided here will help better protect these ecosystems, conserve their biodiversity, and set successful management targets to avoid hypoxia-derived biodiversity losses in coastal waters.

Methods

We searched the literature for reports of hypoxia on the Web of Science and Scholar Google using the keywords “hypoxia,” “marine,” “benthic,” and “sea” and their combinations to guide the search. This search delivered more than 6000 published reports of responses of benthic marine organisms to hypoxia, which were then examined further for the availability of experimental assessments of responses to reduced oxygen content. This search delivered a total of 872 experimental assessments examining the distribution of oxygen thresholds, involving 206 different species of marine benthic organisms.

The outcome of experimental assessments, which follow standard toxicity tests, was summarized using the following indicators of oxygen thresholds: LC50 and SLC50, representing the statistically derived O2 concentration at which 50% of the organisms in a given population die or exhibit sublethal responses, respectively, and LT50, representing the statistically derived time interval at which 50% of a given population dies after exposure to low O2 levels. The vast majority (99.1%) of the experiments designed to assess LT50 chose ≤2 mg O2/liter as experimental conditions, consistent with the widespread acceptance of 2 mg O2/liter as the threshold for hypoxia in the literature (Table S2). Yet this choice indicates that the lethal times reported represent lethal times under acute hypoxia. Only a few experiments testing species particularly sensitive to hypoxia (0.87%) used higher experimental O2 conditions. We analyzed these indicators to extract oxygen thresholds conducive to the effective conservation of marine biodiversity.

ANOVA was used to test for differences in oxygen thresholds among taxonomic groups. ANOVA analysis was conducted after checking for normality using the Shapiro-Wilk test and homogeneity of variance using the Levene test. The Tukey post hoc HSD test was used to determine differences between mean threshold values among taxa (α = 0.05). We also classified the species tested according to their mobility as “fast moving” (fish and a few mollusks, such as octopus), “highly mobile” (most crustaceans), “reduced mobility” (some crustaceans, gastropods, polychaetes, echinoderms, jellyfish, comb fish (ctenophora), priapulids, flatworms, and sipunculida), and “sesile” (anemones, bryozoans, and bivalves). ANOVA was used to test for differences in thresholds with mobility, according to the procedures outlined above. Two-way ANOVA was used to test for the combined effect of taxonomic membership and the extent of mobility of the organisms tested on the experimentally derived thresholds.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

This research is a contribution to the Thresholds integrated project, funded by the European Union 6th Framework Program.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0803833105/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Diaz RJ, Rosenberg R. Marine benthic hypoxia: A review of its ecological effects and the behavioural responses of benthic macrofauna. Oceanogr Mar Biol. 1995;33:245–303. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Diaz RJ. Overview of hypoxia around the world. J Environ Qual. 2001;30:275–281. doi: 10.2134/jeq2001.302275x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stramma L, Johnson GC, Sprintall J, Mohrholz V. Expanding oxygen-minimum zones in the tropical oceans. Science. 2008;320:655–658. doi: 10.1126/science.1153847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chan F, et al. Emergence of anoxia in the California current large marine ecosystem. Science. 2008;319:920. doi: 10.1126/science.1149016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Turner RE, Rabalais NN, Justic D. Gulf of Mexico hypoxia: Alternate states and a legacy. Environ Sci Technol. 2008;42:2323–2327. doi: 10.1021/es071617k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Conley DJ, et al. Long-term changes and impacts of hypoxia in Danish coastal waters. Ecol Appl. 2007;17:S165–S184. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Service RF. Oceanography. New dead zone off Oregon coast hints at sea change in currents. Science. 2004;305:1099–1099. doi: 10.1126/science.305.5687.1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harris LA, Duarte CM, Nixon SW. Allometric laws and prediction in estuarine and coastal ecology. Estuaries Coasts. 2006;29:340–344. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carpenter J. New measurements of oxygen solubility in pure and natural water. Limnol Oceanogr. 1966;11:264–277. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stow CA, Qian SS, Craig JK. Declining threshold for hypoxia in the Gulf of Mexico. Environ Sci Technol. 2005;39:716–723. doi: 10.1021/es049412o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rabalais NN, Turner RE, Wiseman WJ. Gulf of Mexico hypoxia, aka “The dead zone.”. Ann Rev Ecol Syst. 2002;33:235–263. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Renaud ML. Hypoxia in Louisiana coastal waters during 1983: Implications for fisheries. Fish Bull. 1986;84:19–26. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pihl L, Baden SP, Diaz RJ. Effects of periodic hypoxia on distribution of demersal fish and crustaceans. Mar Biol. 1991;108:349–360. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fiadeiro M, Strickla JD. Nitrate reduction and occurrence of a deep nitrite maximum in ocean off west coast of South America. J Mar Res. 1968;26:187–201. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Paerl HW. Assessing and managing nutrient-enhanced eutrophication in estuarine and coastal waters: Interactive effects of human and climatic perturbations. Ecological Engineering. 2006;26:40–54. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Turner RE, Rabalais NN, Swenson EM, Kasprzak M, Romaire T. Summer hypoxia in the northern Gulf of Mexico and its prediction from 1978 to 1995. Mar Env Res. 2005;59:65–77. doi: 10.1016/j.marenvres.2003.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vargo SL, Sastry AN. Acute temperature and low dissolved-oxygen tolerances of brachyuran drab (Cancer irroratus) larvae. Mar Biol. 1977;40:165–171. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hagerman L. Physiological flexibility; a necessity for life in anoxic and sulphidic habitats. Hydrobiologia. 1998;376:241–254. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gray JS, Wu RSS, Or YY. Effects of hypoxia and organic enrichment on the coastal marine environment. Mar Ecol Prog Ser. 2002;238:249–279. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stickle WB, Kapper MA, Liu LL, Gnaiger E, Wang SY. Metabolic adaptations of several species of crustaceans and mollusks to hypoxia: Tolerance and microcalorimetric studies. Biol Bull. 1989;177:303–312. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Saunders RL. Respiration of the Atlantic cod. J Fish Res Board Can. 1963;20:373–386. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Davis J. Minimal dissolved oxygen requirements of aquatic life with emphasis on Canadian species: A review. J Fish Res Board Can. 1975;32:2295–2331. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Anderson SJ, Taylor AC, Atkinson RJA. Anaerobic metabolism during anoxia in the burrowing shrimp Calocaris macandreae Bell (Crustacea, Thalassinidea) Comp Biochem Phys A. 1994;108:515–522. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tallqvist M, Sandberg-Kilpi E, Bonsdorff E. Juvenile flounder, Platichthys flesus (L.), under hypoxia: Effects on tolerance, ventilation rate and predation efficiency. J Exp Mar Biol Ecol. 1999;242:75–93. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dries RR, Theede H. Resistance to oxygen deficiency in marine bottom invertebrates of western Baltic Sea. Mar Biol. 1974;25:327–333. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wu RSS. Hypoxia: From molecular responses to ecosystem responses. Mar Pollut Bull. 2002;45:35–45. doi: 10.1016/s0025-326x(02)00061-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bell GW, Eggleston DB, Wolcott TG. Behavioral responses of free-ranging blue crabs to episodic hypoxia. I. Movement. Mar Ecol Prog Ser. 2003;259:215–225. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pihl L, Baden SP, Diaz RJ, Schaffner LC. Hypoxia-induced structural changes in the diet of bottom-feeding fish and crustacea. Mar Biol. 1992;112:349–361. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nilsson HC, Rosenberg R. Hypoxic response of 2 marine benthic communities. Mar Ecol Prog Ser. 1994;115:209–217. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jorgensen BB. Seasonal oxygen depletion in the bottom waters of a Danish fjord and its effect on the benthic community. Oikos. 1980;34:68–76. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baden SP, Loo LO, Pihl L, Rosenberg R. Effects of eutrophication on benthic communities including fish: Swedish west coast. Ambio. 1990;19:113–122. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Diehl WJ, Mcedward L, Proffitt E, Rosenberg V, Lawrence JM. Response of Luidia clathrata (Echinodermata, Asteroidea) to hypoxia. Comp Biochem Phys A. 1979;62:669–671. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bell GW, Eggleston DB, Wolcott TG. Behavioral responses of free-ranging blue crabs to episodic hypoxia. II. Feeding. Mar Ecol Prog Ser. 2003;259:227–235. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tamai K. Tolerance of Theora fragilis (Bivalvia, Semelidae) to low concentrations of dissolved oxygen. Nippon Suisan Gakkaishi. 1993;59:615–620. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Llanso RJ, Diaz RJ. Tolerance to low dissolved oxygen by the tubicolous polychaete Loimia medusa. J Mar Biol Assoc UK. 1994;74:143–148. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rutherford LD, Thuesen EV. Metabolic performance and survival of medusae in estuarine hypoxia. Mar Ecol Prog Ser. 2005;294:189–200. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Harper SL, Reiber C. Influence of hypoxia on cardiac functions in the grass shrimp (Palaemonetes pugio Holthuis) Comp Biochem Physiol A. 1999;124:569–573. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brooks SPJ, et al. Differential survival of Venus gallina and Scapharca inaequivalvis during anoxic stress: Covalent modification of phosphofructokinase and glycogen-phosphorylase during anoxia. J Comp Physiol B. 1991;161:207–212. [Google Scholar]

- 39.de Zwaan A, Cattan O, Puzer VM. Sulfide and cyanide-induced mortality and anaerobic metabolism in the arcid blood clam Scapharca inaequivalvis. Comp Biochem Phys C. 1993;105:49–54. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Grieshaber MK, Volkel S. Animal adaptations for tolerance and exploitation of poisonous sulfide. Annu Rev Physiol. 1998;60:33–53. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.60.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dubilier N, Windoffer R, Grieshaber MK, Giere O. Ultrastructure and anaerobic metabolism of mitochondria in the marine oligochaete Tubificoides benedii: Effects of hypoxia and sulfide. Mar Biol. 1997;127:637–645. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ellington WR. Holothurian facultative anaerobiosis. Am Zool. 1975;15:808–808. [Google Scholar]

- 43.U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Ambient Aquatic Life Water Quality Criteria for Dissolved Oxygen (Saltwater): Cape Cod to Cape Hatteras. Washington, DC: EPA; 2000. (EPA Publication 822-R-00–012) [Google Scholar]

- 44.de Zwaan A, Cattani O, Vitali G, Cortesi P. Influence of incubation conditions on the anoxic survival of marine bivalves. Static and semi-static incubations. Mar Ecol Prog Ser. 2001;211:169–179. [Google Scholar]

- 45.de Zwaan A, Cortesi P, Cattani O. Resistance of bivalves to anoxia as a response to pollution-induced environmental stress. Sci Total Environ. 1995;171:121–125. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Alderdice D, Forrester CR. Effects of salinity, temperature, and dissolved oxygen on early development of Pacific cod (Gadus macrocephalus) J Fish Res Board Can. 1971;28:883–902. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Das T, Stickle WB. Detection and avoidance of hypoxic water by juvenile Callinectes sapidus and C. Similis. Mar Biol. 1994;120:593–600. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wannamaker CM, Rice JA. Effects of hypoxia on movements and behavior of selected estuarine organisms from the southeastern United States. J Exp Mar Biol Ecol. 2000;249:145–163. doi: 10.1016/s0022-0981(00)00160-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Modig H, Olafsson E. Responses of Baltic benthic invertebrates to hypoxic events. J Exp Mar Biol Ecol. 1998;229:133–148. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lu L, Wu RSS. An experimental study on recolonization and succession of marine macrobenthos in defaunated sediment. Mar Biol. 2000;136:291–302. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rosenberg R, Agrenius S, Hellman B, Nilsson HC, Norling K. Recovery of marine benthic habitats and fauna in a Swedish fjord following improved oxygen conditions. Mar Ecol Prog Ser. 2002;234:43–53. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Matthews MA, McMahon RF. Effects of temperature and temperature acclimation on survival of zebra mussels (Dreissena polymorpha) and Asian clams (Corbicula fluminea) under extreme hypoxia. J Molluscan Stud. 1999;65:317–325. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vistisen B, Vismann B. Tolerance to low oxygen and sulfide in Amphiura filiformis and Ophiura albida (Echinodermata: Ophiuroidea) Mar Biol. 1997;128:241–246. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Diaz RJ, Rosenberg R. Spreading dead zones and consequences for marine ecosystems. Science. 2008;321:926–929. doi: 10.1126/science.1156401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.