Abstract

Comparative epidemiological study of minor cervical spine trauma (frequently referred to as whiplash injury) based on data from the Comité Européen des Assurances (CEA) gathered in ten European countries. To determine the incidence and expenditure (e.g., for assessment, treatment or claims) for minor cervical spine injury in the participating countries. Controversy still surrounds the basis on which symptoms following minor cervical spine trauma may develop. In particular, there is considerable disagreement with regard to a possible contribution of psychosocial factors in determining outcome. The role of compensation is also a source of constant debate. The method followed here is the comparison of the data from different areas of interest (e.g., incidence of minor cervical spine trauma, percentage of minor cervical spine trauma in relationship to the incidence of bodily trauma, costs for assessment or claims) from ten European countries. Considerable differences exist regarding the incidence of minor cervical spine trauma and related costs in participating countries. France and Finland have the lowest and Great Britain the highest incidence of minor cervical spine trauma. The number of claims following minor cervical spine trauma in Switzerland is around the European average; however, Switzerland has the highest expenditure per claim at an average cost of €35,000.00 compared to the European average of €9,000.00. Furthermore, the mandatory accident insurance statistics in Switzerland show very large differences between German-speaking and French- or Italian-speaking parts of the country. In the latter the costs for minor cervical spine trauma expanded more than doubled in the period from 1990 to 2002, whereas in the German-speaking part they rose by a factor of five. All the countries participating in the study have a high standard of medical care. The differences in claims frequency and costs must therefore reflect a social phenomenon based on the different cultural attitudes and medical approach to the problem including diagnosis. In Switzerland, therefore, new ways must be found to try to resolve the problem. The claims treatment model known as “Case Management” represents a new approach in which accelerated social and professional reintegration of the injured party is attempted. The CEA study emphasizes the fundamental role of medicine in that it postulates a clear division between the role of the attending physician and the medical expert. It also draws attention to the need to train medical professionals in the insurance business to the extent that they can interact adequately with insurance professionals. The results of this study indicate that the usefulness of the criterion of so-called typical clinical symptoms, which is at present applied by the courts to determine natural causality and has long been under debate, is inappropriate and should be replaced by objective assessment (e.g. accident and biomechanical analysis). In addition, the legal concept of adequate causality should be interpreted in the same way in both third party liability and social security law, which is currently not the case.

Keywords: Minor cervical trauma, Cervical spine injury, Whiplash injury

Introduction

Minor injury to the cervical spine, frequently referred to as whiplash injury, is a topic that occupies and concerns physicians, lawyers, accident analysts and insurers. However, the figures reported in the literature for claims frequency after minor cervical injury vary widely. For example, in Lithuania [9] or in Greece [10] minor cervical spine injury is reported to be an almost non-existent condition. In contrast, studies from Germany [13] and Great Britain [17] indicate an increase in the claims frequency for minor cervical spine injuries in recent years. Interestingly, minor cervical spine injuries resulting from road traffic accidents [6] are considered to be an important cause of disability in Great Britain, whereas a search for studies from France on the same topic produced no results in PubMed and publications in international journals seemed to be restricted to one cited review article only [1]. Irrespective of possible criticisms regarding quality of research carried out in the field of minor cervical spine injury by the Quebec Task Force [15], there are indeed an increasing number of publications regarding the legal [3], medical and biomechanical aspects of minor cervical spine injury [2, 7, 8, 11, 14, 16]. Results of the studies are still confusing. Some studies indicate poor clinical outcome based mainly on psychosocial factors and lack of correlation with collision parameters [12], other studies suggest a prominent correlation between poor clinical outcome and compensation issue [2, 9], while other researchers refute any fundamental influence of psychosocial factors or the compensation issue (see summary in [14]).

Complementary to the existing large body of investigational reports, a comparative study on minor cervical spine injury was brought out at the end of 2004 by the Comité Européen des Assurances (CEA), together with the Association for the Study and Compensation of Bodily Injury (AREDOC in France), and the European Confederation of Experts in Assessing and Compensating Bodily Injury (CEREDOC). This study focuses on the number and cost of minor cervical spine injury claims in ten European countries. The study results can be downloaded from the Internet site of the Swiss Insurance Association in German, French and English at: http://www.svv.ch.1

The aim of this paper is not to analyse the complex topic of minor cervical spine injury in detail from a medical or legal point of view. It will focus to some extent on the situation in Switzerland. Primarily, this paper focuses on claims frequency and expenditure for this type of injury in the participating countries in order to comment on the summary of reported results from the national insurance organizations of ten European countries, namely Switzerland, Belgium, Germany, Spain, Finland, France, Italy, the Netherlands, Norway and Great Britain.

Origin of the study and its contents

Over the past 10 years, insurance companies have noticed a rise in costs for minor cervical spine injury. Interestingly, in some European countries the changes are associated with an increased incidence of minor cervical spine injury leading to higher costs, whereas in other countries dramatic changes relating to claims frequency for minor cervical spine injury have not been recorded. To investigate this discrepancy and obtain objective knowledge on this topic, CEA and AREDOC decided to carry out a collaborative comparative study on the incidence and cost of minor cervical spine injury in ten European countries.

The aim of the CEA/AREDOC-study was to assess patterns of trauma incidence and related expenditure in different countries, including compensation strategies in motor liability insurance, as well as the various tools that insurance companies have at their disposal to deal with the claims under discussion including their overall policies.

In the study, the following main areas are addressed: epidemiological data (e.g., incidence of minor cervical spine injury), medical background data (e.g., specificity of physicians’ training, type of medical investigations) and legal aspects (concept of causality, identifiable damage) of measures taken by the insurers as well as other pertinent considerations. Some further aspects of interest were not addressed such as technical aspects of vehicle design (e.g., headrests and seats). The same applies to the delicate topic of malingering. The study did not examine the time taken to handle the cases, which is closely related to the time taken for medical treatment and for the medical expert opinion. A brief exchange of views on this subject indicated large differences between countries, differences that were confirmed by the experience of the insurance companies’ claims services working on international claims. The investigations needed to verify this general trend would have gone beyond the scope of this study.

Definition of minor cervical trauma

In order to provide a comparable approach when dealing with minor cervical trauma a group of medical professionals proposed the following definition:

In order to analyse the possible after-effects of phenomena with no initial detectable injury, a minor or benign cervical trauma may be defined as a lesion of the cervical spine, caused by acceleration–deceleration mechanisms (due for example to pronounced extension and/or flexion more or less accompanied by torsion), without neurological complications and without affecting the osseous, nervous or ligamentary-disc structures, which may lead to painful symptoms when at rest or during movement and be accompanied by reduced mobility of the cervical spine. The text can be found on http://www.svv.ch CEA-study.1

The frequently used term “whiplash injury” is not mentioned in this definition. This is not an oversight but the general conclusion was that “whiplash injury” does not represent a diagnosis but only describes a mechanism that may lead to a minor cervical spine injury. The use of the term “whiplash injury” in reality leads to confusion between the injury mechanism and the possible consequences of this mechanism and thereby causes misconceptions. In comparison, no one would say that someone is suffering from a kick if the person suffered a fractured shinbone resulting from a kick! In addition, there was a consensus that even if the “whiplash mechanism” could be proven, it would not necessarily lead to an injury. The CEA/AREDOC-study was deliberately limited to minor cervical spine injuries as only these cause problems due mainly to a lack of objective findings. Finally, only isolated minor cervical spine injuries requiring treatment were included in the evaluation regardless of whether long-term impairment followed. Cases of multiple injuries were excluded.

Insurance data

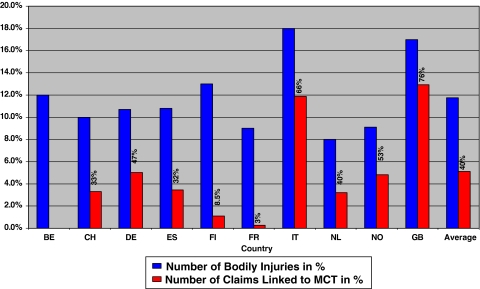

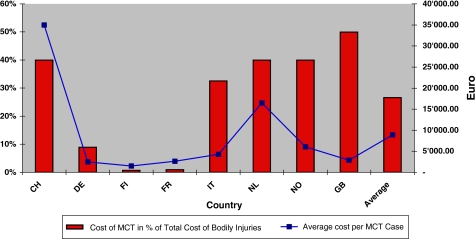

The insurance data are summarized in Figs. 1 and 2. Figure 1 shows the number of claims in ten European countries and Fig. 2 shows expenditure for minor cervical spine injury. It should be mentioned that the data only refer to motor liability claims.

Fig. 1.

Number of bodily injuries

Fig. 2.

Cost of bodily injuries

Number of bodily injuries (Fig. 1)

Bodily injuries represent between 8% (the lowest incidence rate in the Netherlands) and 18% (the highest incidence rate in Italy) of all insurance claims, i.e., including both bodily injuries and property damage. Thus, the incidence of claims is twice as high in Italy as it is in the Netherlands.

Minor cervical spine injuries taken as a percentage of all bodily injuries range between 3% (the lowest percentage in France) and 76% (the highest percentage in Great Britain). The mean value for all ten countries is 40%. Minor cervical spine injuries as a percentage of all bodily injuries are therefore 25 times higher in Great Britain than in France. Two of the participating countries show considerably low percentages of minor cervical spine injury in relation to all bodily injuries, i.e., France at 3% and Finland at 8.5%. These two countries are followed by Spain (32%), Switzerland (33%), the Netherlands (40%) and Germany (47%). Considerably high percentages of minor cervical spine injuries in relation to all bodily injuries are found in Norway (53%) and Italy (66%). Finally, there is an almost amazing 76% in Great Britain.

Costs of bodily injuries (Fig. 2)

In terms of percentage of total expenditure for personal damage, expenditure for minor cervical spine injuries is highest in Great Britain where it reaches a value of 50%. In Switzerland, the Netherlands and, Norway 40% of total expenditure relates to minor cervical spine injury, whereas in Italy this value is about 33%. The countries with the lowest expenditure for minor cervical spine injury are France (0.5%), Finland (0.78%) and Germany (9%). In the participating countries, the average cost for minor cervical spine injury as a subdivision of all bodily injuries is 27%. With an average of €35,000 Switzerland has the highest cost per claim followed by the Netherlands (€16,500) and Norway (€6,050). The countries with the lowest average cost per claim are Finland (€1,500), Germany (€2,500), France (€2,625) and Great Britain (€2,878). The average cost for all participating countries is slightly less than €9,000.

With regard to claims frequency, Switzerland occupies a midfield position within the European average. In contrast, with regard to expenditure, the CEA-study shows considerable differences between the countries in terms of total costs for minor cervical spine trauma as well as the average cost per claim. For both these aspects Switzerland is in a leading position. Switzerland shares a percentage cost of 40% with the Netherlands and Norway. Overall expenditure in Switzerland, based on the average cost per claim, amounts to the sum of 500 million Swiss francs in motor liability insurance.

The values for Switzerland are taken from across the whole country. However, statistical data from insurance companies show that awareness of minor cervical injuries in German-speaking Switzerland is much higher than in the French- and Italian-speaking parts. How is this expressed in terms of overall expenditure and cost per claim?

With regard to the first point, statistical information from the collection center of accident insurance statistics (http://www.ssuv.ch)2 on mandatory accident insurance shows no difference between the German-speaking and the French- or Italian-speaking parts of the country when cervical spine injury is compared with the total number of injuries sustained by full-time employees. These statistics show that the number of injuries doubled from 1990 to 2002—a development that is attributed to a steady nationwide increase in mobility and vehicle density.

However, statistics also show that, within the same time frame, the increase in services for treatment costs, daily sickness benefits and present value of annuities in different regions of Switzerland developed in very different ways. The relevant expenditure doubled in the French- and Italian-speaking parts of Switzerland while in the German-speaking part, the amount increased by a factor of five. It deserves mention that expenditure for present value of annuities increased eight-fold.

These very different developments in the German-speaking and French- or Italian-speaking parts of the country cannot be explained by inferior medical treatment as this would lead to more cases of invalidity in German-speaking Switzerland. It seems rather that the pattern of national differences identified by the results of the CEA-study for Europe as a whole is reflected within Switzerland. This parallelism allows for speculation that cultural setting and sensitivity or awareness of the problem in the wider sense can be considered as playing a decisive role in the medical and legal treatment of minor cervical spine injury. The issue of heightened awareness of the problem appears to be supported by the results of a recently published Canadian study that investigated the relationship between early aggressive treatment and delayed recovery [5]. The higher number of claims in German-speaking Switzerland may be attributed to the work of the proactive associations that represent injured persons and encourage expectant behavior.

Medical aspects

Medical aspects relate to the medical training required to devise an independent expert opinion on personal injury and to conduct the medical investigations necessary to verify minor cervical trauma.

Education regarding the assessment of bodily injuries

Two groups of countries can be distinguished here. In Belgium, Spain and France specialized expert training is mandatory and graduates receive a university diploma. In other countries (Switzerland, Germany, Finland, Great Britain, Italy and Norway), insurance companies allow bodily injuries to be assessed by both acknowledged experts and medical specialists without specific training in insurance questions. In Switzerland specialized medical training in accident insurance has been offered specifically for this reason since 1998, although graduates do not receive a certificate of qualification as experts in medico-legal affairs. A so-called “contradictory assessment” whereby each party chooses experts who must then agree on a common conclusion leads to a substantial simplification of the investigation procedure but is unknown in Switzerland.

Medical investigation to diagnose minor injury to the cervical spine

In Belgium, Switzerland and Spain the patient’s medical history is the first step toward diagnosis. In Belgium and Finland this is followed by collation and summary of all available information. In addition, most countries refer to various clinical and imaging examinations. It is important to emphasize that only France and the Netherlands indicate the inclusion of circumstances of the accident in the diagnosis. France also mentions that the victim’s previous state of health is examined and a discussion between the doctor and patient takes place in order to assess to what extent the complaints are due to the injuries; without this accountability an evaluation of the after-effects is not possible.

Legal aspects

Each country participating in the study uses the term causality. However, each country also uses a different approach. Nevertheless, it can be stated that liability to pay damages only exists if the damage can be attributed to the accident, whereby the requirements for accountability vary. Only Swiss law makes an exact distinction between natural and adequate causality; natural causality is a point of fact and lies within the competence of the doctor, whereas adequate causality is a point of law.

Value of biomechanics

The relevance of accident analysis and biomechanics for the evaluation of causality varies greatly between the participating countries. In Germany, accident analysis and biodynamic experiments are taken into consideration in order to assess whether the accident could have caused a cervical trauma. The majority of courts in Germany refuse to acknowledge cervical trauma as a cause of symptoms if the velocity change (frequently referred to as delta-v) is below 10 km/h. If delta-v is between 10 and 30 km/h, the courts in Germany presume the causality of symptoms, and clear causality between trauma and symptoms is considered if delta-v is greater than 30 km/h.

With this in mind, there is also a tendency in Switzerland to promote biomechanical assessment because this may provide useful information on technical values relating to the victim’s medical condition.

Identifiable damage following quantifiable and non-quantifiable injuries and malingering

Every country’s report shows that quantifiable and non-quantifiable injuries are incorporated into its compensation system, although compensation of non-quantifiable injuries represents a fundamental problem in Switzerland. The delicate question of possible malingering is then posed. Unfortunately, malingerers exist. This is shown by some recent cases in Switzerland that were subject to criminal proceedings and also attracted media attention. Cases of malingerers show the difficulties with which doctors are confronted when giving a diagnosis of minor cervical spine injury exclusively on grounds of subjective complaints. At the same time such cases also show the importance of a call for appropriate action to be taken to develop a strict and objective methodology to serve as standard procedure and to introduce an interdisciplinary approach that includes accident-analytic and biomechanical findings.

Studies on minor cervical spine injury

All the countries participating in the survey reported studies on the topic of minor cervical spine injury that were either based on the findings of expert committees (Belgium), or implemented by universities (Finland), and/or financed by insurance companies (Switzerland, Germany).

Three Swiss studies were cited by the CEA et al. in their comparative study and these were subsequently presented in greater detail by Chappuis and Soltermann [4]:

Randomized study with four treatment modalities for chronic pain after cervical spine distortion at the University of Bern. This study, which was funded by the Swiss Insurance Association, the Swiss Accident Insurance Fund and the Swiss National Science Foundation, showed the benefit of psychotherapeutic treatment and proved that a slight cervical spine distortion without concussion does not cause any structural brain damage.

The RAND-study examined the risk factors of chronic injury. The results of the study have enabled a concept for managing MCT claims to be drafted by insurance companies. The study can be found on http://www.svv.ch).1

The CRASH-study supports efforts aimed at defining quality standards for the analysis of accident dynamics (http://www.agu.ch).3

Existence of lobbies

In Belgium, Switzerland, Germany, the Netherlands and Norway there are associations that support individuals who report symptoms of minor cervical spine injury usually following road traffic accidents. With the exception of Norway, which did not reply on this subject, all countries in which there are injured persons associations (whether or not specifically assisting MCT victims) report that they have the support of doctors and lawyers. In addition, the Swiss report points out that the medical profession is divided on this issue so that scientific agreement and objective evaluation seem unlikely from the point of view of the insurance companies.

Recommendations to national associations

As a result of the study the CEA addressed five recommendations to the national insurance associations. These are quoted in full below [4]:

Clearly identify the role and function of the doctor, i.e. whether he is acting as a consultant or a GP. The study suggests that the objectivity of the expert’s medical opinion depends on this distinction. This objectivity is based on special training in giving independent medical expert opinions and in assessing bodily injury.

Provide specialized training for medical experts. Assessment is a scientific discipline that can be taught. It is characterized by strict methodology that ensures its formal exactness and defines the objective quality standards to be applied by those responsible for settling bodily injury claims.

Ensure better collaboration between doctors, lawyers, insurers and biodynamics experts. Cervical spine injuries show the need for a multi-disciplinary approach enabling the problem to be viewed in its entirety. There could be misunderstanding between doctors and lawyers arising from the fact that doctors practice an empirical science whereas lawyers practice a normative one. Hence, lawyers have a problem understanding the difficulties of doctors with differential diagnosis, and doctors have a problem understanding legislation on causality.

Develop active communication on problems relating to compensation of cervical injuries (publications in medical and legal reviews, topics for legal or medical seminars, information for the general public, etc.). The considerable differences in claims and average cost per claim between countries, which all have a high-level of medical services and relatively similar compensation systems, show that cervical injuries are a phenomenon of society rather than a purely medico-legal problem.

Underline the fact that technical developments associated with vehicle design are not sufficient to resolve the entire problem of cervical injury claims.

Conclusion

The comparative study of minor cervical spine injury, in which ten European countries participated, shows huge differences between the countries both in regard to minor cervical spine injury as a proportion of all bodily injuries and with regard to expenditure. Possibly, the most intriguing result emerging from this study is the roughly 25-fold higher percentage of minor cervical spine injury in Great Britain compared to France when focussing on minor cervical spine injury as a proportion of all bodily injuries. Both these countries have almost the same population size and both have urban conglomerations of megalopolic size. Furthermore, these two countries do not differ significantly regarding the density of the health system network. Italy is also a country with almost the same population size as France and Great Britain, at least two large urban conglomerations and a similar density of health system network, but Italy has a 22-fold higher percentage of minor cervical spine injury than France. Based on these facts one should expect a similar claims frequency for minor cervical spine injury in all these countries. The huge differences in minor cervical spine injury as a percentage of all bodily injuries between these countries may reflect the most important problem with this type of injury, namely, differential diagnosis. Interestingly, in contrast to France, neither Great Britain nor Italy provide specialized training for medical professionals in the assessment of accident victims. For this reason, it appears that diagnostic procedure in countries with higher percentages of minor cervical spine injury (Germany and Norway also belong to this group and do not offer specialized training) does not aim to differentiate between the reported or presumed injury mechanism (i.e., whiplash mechanism) and a diagnosis based on empirical medical findings. With regard to minor cervical spine injury as a percentage of all bodily injuries, Switzerland ranks in the midfield with almost the same percentage as Spain. This finding is in contrast to the above assumption because Spain provides specialized training whereas Switzerland does not. Moreover, Finland does not provide specialized training in the assessment of accident victims but has a considerably lower percentage of minor cervical spine injuries in relation to all bodily injuries. Interestingly, bodily injuries in Finland are in third place after Great Britain and Italy. It follows that the differences between countries in minor cervical spine injuries as a percentage of all bodily injuries may reflect the appropriateness of diagnostic action; however, this alone does not fully explain the differences.

When focusing on cost of injury, Switzerland is in the group of countries which has the highest costs. According to the Swiss Insurance Association 40% of the compensation of motor vehicle liability insurance for personal injuries goes on minor cervical spine injury totally a sum of CHF 500 million per year. In addition, the average cost per claim of €35,000.00 compared to the European average of €9,000.00 is by far the highest of all the countries participating in the study. From this perspective, minor cervical spine injuries are currently becoming a cause for concern in Switzerland. Furthermore, mandatory accident insurance statistics show very large differences between German-speaking and French- or Italian-speaking Switzerland, where the cost of claims in the period 1990–2002 doubled, while those in the German-speaking part of Switzerland quintupled.

It can be assumed that all the countries participating in the study have a high standard of medical care, comparable density of health network system, and similar compensation systems. Thus the results of the CEA/AREDOC-study seem to indicate that the differences between numbers and costs of minor cervical spine injuries reflect a medical–social phenomenon based, in the broadest sense, on different cultural attitudes rather than exclusively representing a medico-legal problem. This hypothesis particularly applies to Switzerland, where expenditure for minor cervical trauma by insurance companies offering mandatory accident insurance has developed very differently in the German-speaking and the French- and Italian-speaking parts of Switzerland.

The fact that the European population is traveling a lot in private motor vehicles increases the risk of accidents. This requires a reliable, Europe-wide system of diagnostic procedure for accident victims in order to establish comparable and reliable action to eliminate sequelae (e.g., by treatment methods, addressing medico-legal issues). New ways must therefore be found in Switzerland to identify and resolve the problems and find a way out of what appears to be a cul-de-sac. The model of damage treatment, also known as case management, is a new approach that tries to accelerate the social and vocational reintegration of the accident victim. The future will show whether this model will come up to the expectations.

The recommendations based on the results of the CEA-study also provide interesting ideas with regard to possible guidelines. The recommendations emphasize the fundamental role of medicine by clearly separating the role of the treating physician from the role of the medical expert and also highlight the necessity for specific training of the medical consultant.

The gaps in Swiss insurance medicine are apparent. They emerge not only from the frequently rather moderate quality of the expert’s assessments, but also from the inappropriate evaluation of causality or inability to work due to a lack of legal knowledge. Swiss Insurance Medicine (SIM, http://www.swiss-insurance-medicine.ch)4 and the Academy of Swiss Insurance Medicine (ASIM, http://www.asim.unibas.ch)5 recently founded by the University of Basel may offer a different approach to the problems. It is based on promoting an interdisciplinary approach between medicine, law, insurance and biodynamics, as the CEA-study recommendations suggest. It appears that there is actually no use in looking for a solution to the problem of minor cervical spine injuries in any one of the individual disciplines in isolation when it is already apparent that medicine and law hold different points of view.

It is indeed important to establish both a diagnostic position and methodological principles based on objective and useful criteria for the execution of an expert assessment that will be understood and accepted by those concerned.

In legal circles, objective statements based on accident dynamics and biodynamics, that would replace the current typical clinical symptoms applied by the courts to determine natural causality, would be welcomed. It is also desirable that the legal term of adequate causality in liability and social security law is given the same status as natural causality, which is currently not the case.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Footnotes

Swiss Insurance Association (SIA), C·F. Meyer-Strasse 14, P·O. Box 4288, 8022 Zurich, Switzerland

Sammelstelle für die Statistik der Unfallversicherung UVG (SSUV), c/o Suva, Fluhmattstrasse 1, 6002 Luzern, Switzerland

Working Group on Accident Mechanics; Research, Reconstruction, Biomechanics, Prevention; AGU, Winkelriedstrasse 27, 8006 Zürich, Switzerland

Swiss Insurance Medicine (SIM), c/o WIG, Im Park, St. Georgenstrasse 70, P·O. Box 958, 8401 Winterthur, Switzerland

Academy of Swiss Insurance Medicine (asim), Universitätsspital Basel, Petersgraben 4, 4031 Basel, Switzerland

CEA: The Comité Européen des Assurances represents the European insurance industry in the national insurance organizations of 33 countries; http://www.cea.assur.org.

AREDOC: Association pour l’Etude de la Réparation du Dommage Corporel (Association for the Study and Compensation of Bodily Injury); http://www.aredoc.com.

CEREDOC: Confédération Européenne d’Experts en Evaluation et Réparation du Dommage Corporel (European Confederation of Experts in Assessing and Compensating Bodily Injury); http://www.ceredoc.it.

Comments to this paper is available at

doi:10-1007/s00586-008-736-4

doi:10-1007/s00586-008-735-4

doi:10-1007/s00586-008-734-6

Contributor Information

Guy Chappuis, Email: guy.chappuis@baloise.ch.

Bruno Soltermann, Email: bruno.soltermann@svv.ch.

References

- 1.Benoist M. Whiplash injury of the cervical spine. Presse Med. 2000;29:196–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cassidy JD, Carroll L, Côté P, Lemstra M, Berglund A, Nygren A. Effects of eliminating pain and suffering on the incidence and prognosis of whiplash claims. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1179–1186. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200004203421606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Castro W, Lemcke H, Schilgen M, Lemcke L. So-called “whiplash trauma”—legal and medical considerations. Chirurg. 1998;69:176–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chappuis G, Soltermann B. Schadenhäufigkeit und Schadenaufwand bei leichten Verletzungen der Halswirbelsäule: Eine schweizerische Besonderheit? Schweiz Med Forum. 2006;6:398–406. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Côté P, Hogg-Johnson S, Cassidy JD, Carroll L, Frank JW, Bombardier C. Early aggressive care and delayed recovery from whiplash: isolated finding or reproducible result? Arth Rheum. 2007;57:861–868. doi: 10.1002/art.22775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crouch R, Whitewick R, Clancy M, Wright P, Thomas P. Whiplash associated disorder: incidence and natural history over the first month for patients presenting to a UK emergency department. Emerg Med J Feb. 2006;23(2):114–118. doi: 10.1136/emj.2004.022145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dehner C, Elbel M, Schick S, Walz F, Hell W, Kramer M. Risk of injury of the cervical spine in sled tests in female volunteers. Clin Biomech. 2007;22:615–622. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2007.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harder S, Veilleux M, Suissa S. The effect of socio-demographic and crash-related factors on the prognosis of whiplash. J Clin Epidemiol. 1998;51:377–384. doi: 10.1016/S0895-4356(98)00011-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Obelieniene D, Schrader H, Bovim G, Miseviciene I, Sand T. Pain after whiplash-a prospective controlled inception cohort study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1999;66:279–283. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.66.3.279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Partheni M, Constantoyannis C, Ferrari R, Nikiforidis G, Voulgaris S, Papadakis N. A prospective cohort study of the outcome of acute whiplash injury in Greece. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2000;18:67–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Radanov BP, Sturzenegger M, Di Stefano G. Long-term outcome after whiplash injury - A two years follow-up considering features of accident mechanism, somatic, radiological and psychosocial findings. Medicine. 1995;74:281–297. doi: 10.1097/00005792-199509000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Richter M, Ferrari R, Pottex D, Kuensebeck HW, Blauth M, Krettek C. Correlation of clinical findings, collision parameters, and psychological factors in the outcome of whiplash associated disorders. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2004;75:758–764. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2003.026963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Richter M, Otte D, Pohlmann T, Krettek C, Blauth M. Whiplash-type neck distortion in restrained car drivers: frequency, causes and long-term results. Eur Spine J. 2000;9:177–180. doi: 10.1007/s005860000177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scholten-Peeters GGM, Verhagen AP, Bekkering GE, van der Windt DAWM, Barnsley L, Oostendorp RAB, Hendriks EJM. Prognostic factors of whiplash-associated disorders: a systematic review of prospective cohort studies. Pain. 2003;104:303–322. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(03)00050-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Spitzer WO, Skovron ML, Salmi LR, et al. Scientific monograph of the Quebec task force on whiplash-associated disorders: redefining “whiplash” and its management. Spine. 1995;20:1S–73S. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199501000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sturzenegger M, Radanov BP, Di Stefano G. The effect of accident mechanisms and initial findings on the long-term course of whiplash injury. J Neurol. 1995;242:443–449. doi: 10.1007/BF00873547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tomlinson PJ, Gargan MF, Bannister GC. The fluctuation in recovery following whiplash injury 7.5 year prospective review. Injury. 2005;36:758–761. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2005.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]