Abstract

For patients with ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament (OPLL) who have neurological-symptoms, surgery is necessary but not always effective. Various clinical factors influence the surgical outcome. The studies identifying these factors have been inconclusive and conflicting. It is essential for surgeons to understand the significance of the factors and choose the optimal therapeutic strategy for OPLL. The objective of this review is to determine the clinical factors predictive of the surgical outcome of cervical OPLL. The authors conducted a review of literature published in the English language. They examined studies in which the correlation between clinical factors and outcome were statistically evaluated. The results showed that the traverse area of the spinal cord, the spinal cord-evoked potentials (SCEPs), the increase of the range of motion in the cervical spine (ROM), diabetes, history of trauma, the onset of ossification of the ligament flavum (OLF) in the thoracic spine, snake-eye appearance (SEA) and incomplete decompression may be predictive factors. Age at surgery seems to be closely related to the outcome of posterior surgical procedure. Whether the neurological score, OPLL type, pre-operative duration of symptoms, focal intra-medullar high signal intensity in T2-weighted (IMHSI) and progression of OPLL or kyphosis and expansion of the spinal canal predict the surgical outcome remains unclear. The use of uniform neurological score and proper statistic analysis should facilitate comparison of data from different studies. It is important to analyze the effect of each factor on groups with different surgical procedures as well as patients with different compressive pathology. Research on the etiology and pathology of cervical myelopathy due to OPLL should be helpful in precisely understanding these clinical factors and predicting surgical outcome.

Keywords: Ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament, Cervical spine, Prognostic factors, Surgical outcome

Introduction

Ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament (OPLL) has been known to be an important cause of cervical myelopathy in both Asian and Western countries. Although many clinical features of cervical OPLL are similar to those of cervical spondylotic myelopathy or cervical disc herniation, it also has several unique characteristics. Cervical OPLL frequently involves multiple levels. Sometimes it progresses after operation without the removal of the ossification foci and occasionally; when it densely adheres the dura mater, direct anterior removal may be very difficult. Whether conservative or operative treatment should be chosen for non-neurological symptomatic patients with OPLL remains controversial due to lack of complete knowledge of the natural history in OPLL. While for patients with neurological symptoms, surgery is necessary and several operative procedures could be adopted. Such as: anterior discectomy and fusion, anterior corpectomy with fusion, anterior floating method, laminectomy and laminoplasty. Although all of these surgical methods have been shown effective, poor results are frequently reported. It indicates that various clinical factors may be related to or could affect the operative outcome. Meanwhile, these factors also influence the choice of surgeons for the treatment of cervical OPLL. Recently more and more studies have focused on identifying these predictive factors, but the results of these studies have often been inconclusive and even conflicting. To understand the significance of these factors and determine their relationship to the surgical-outcome of cervical OPLL, we summarize and discuss the factors, and try to explain the conflicting results among the studies in present literature.

Materials and methods

Relevant literature search was performed using Pub-Med (http://www.pubmed.gov). The key words for the literature search included “ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament,” “cervical,” “treatment outcome” and “surgery”. The search was performed with limiting factors of “human” and “English language”. Some papers were found by manual methods. Additional articles identified from these references that contained relevant supporting information were then included. The search was performed by one reviewer.

After excluding identical papers, we carried out a selection of peer-reviewed articles to include. The selected articles should meet the following criteria:

The literature published between 1975 and April 2007 was included.

The paper that consists of 10 or more cases and focused on the assessment of predicators for surgical outcome of OPLL patients by statistic analysis was included.

Reviewed articles were limited to the articles referring only to cervical OPLL. The literature pertaining to thoracic or lumbar OPLL was excluded. Those referred to both of OPLL and cervical spondylotic myelopathy or disc herniation were also excluded.

If the articles were reported by the same authors or from the same institute, the most currently reported paper with detailed and complete clinical data would be included. If an equal number of patients were reported by the same authors, the articles with the most information were selected.

The information extraction of articles was done independently to minimize selection bias and errors. All abstracts were printed and close-reading was performed by two surgeons with rich experience in spinal surgery. The different information extracted from the same article was compared and reread till the information could be agreed upon. If it was difficult for them to obtain a consensus, a third reviewer was consulted. Finally, a total of 19 papers were selected to review. Full text of each paper was found, then, careful reading and data extraction was done independently by the two surgeons mentioned above. At last, all extracted information were imported into an electronic spread sheet—Microsoft Excel.

Results

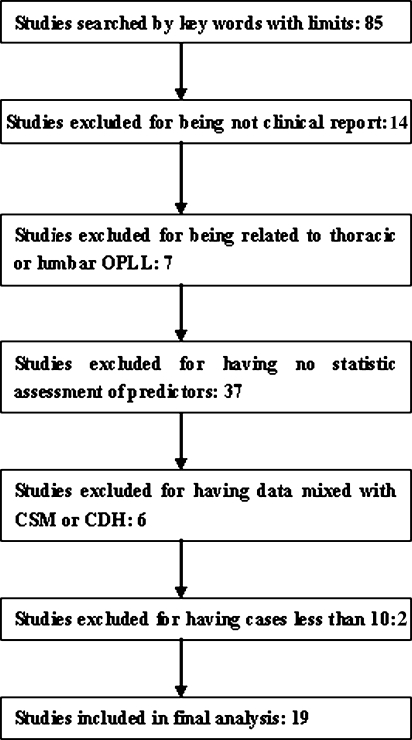

We found a total of 19 studies consisting of 10 patients or more which statistically evaluated the correlation between clinical factors and surgical outcome (Fig. 1). The patients’ demographics of each study are summarized in Table 1. Four studies used the single anterior approach. Nine studies used the single posterior approach. In another six studies, both the anterior and posterior approaches were used and the data was jointly analyzed. The surgical outcome was assessed by post-operative neurological function or its recovery rate. The mean range of follow-up was approximately 1–14.7 years. The clinical factors evaluated differed from study to study and included age, sex, ossified type, pre-operative duration of symptoms, pre-operative neurological score, involved interspaces, surgical levels, diabetes, history of trauma, progression of ossification or kyphosis and many radiographic assessments. The results of the 19 studies are summarized in Table 2. The factors which were evaluated in more than five studies included age, duration of symptoms, ossification type, pre-operative neurological score, involved spaces, and occupational ratio, progression of ossification or kyphosis and change in the cervical alignment (Table 3). Other factors were evaluated in less than four studies. Clinical factors and the number of studies confirming or not confirming these factors as predictors and the distribution of these studies according to surgical approaches are also shown in Table 3.

Fig. 1.

The flow chart of the studies included or excluded according to the criteria and number

Table 1.

Summary of clinical studies on statistic evaluation of the correlation between clinical factors and surgical outcome

| Author and Year | Surgical approach | No. of case (total/OPLL) | M/F | Mean age | Type of OPLL (C/S/M/O) | Pre-operative mean symptom duration | Pre-operative mean neurologic score/tool | Post-operative mean neurologic score | Recovery rate (%) | Mean FU |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Koyanagi et al. [20] | A, P | 39 | NA | 59 | NA | 16.9 mos | 7.5/JOA | 12 | 45 | NA |

| Okada et al. [30] | A, P | 23 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 9.7/JOA | 13.6 | 54.7 | NA |

| Goto et al. [10] | A, P | 115 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Inoue et al. [12] | P | 26 | 20/6 | 55.6 | NA | NA | 8.9/JOA | 13.9 | 65.2 | 104.2mos |

| Nakamura et al. [26] | A, P | 91 | 71/20 | 59 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Fujimura et al. [9] | A, P | 55 | 46/9 | 56.8 | NA | 18.6 mos | 8.7/JOA | 12.8 | 49.3 | 80.3 mos |

| Kato et al. [16] | P | 44 | 37/7 | 57 | 15/2/26/1 | 36.8 mos | 7.6/JOA | 10.8 | 32.8 | 14.1 yrs |

| Onari et al. [32] | A | 30 | 22/8 | 51.3 | 10/7/11/2 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 14.7yrs |

| Seichi et al. [33] | P | 35 | 26/9 | 55 | NA | NA | 8.5/JOA | 11.9/JOA | NA | 153mos |

| Matsuoka et al. [24] | A | 63 | 45/18 | 57 | 15/12/35/1 | 3.8 yrs | 8.3/JOA | 13.5 | 59.3 | 13 yrs |

| Iwasaki et al. [13] | P | 64 | 43/21 | 56 | 18/13/31/2 | NA | 8.9/JOA | 13.7 | 60 | 12.2 yrs |

| Ogawa et al. [27, 28] | P | 72 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 9.2/JOA | 14.2 | NA | ≥5 yrs |

| Uchida et al. [36] | A, P | 58 | 39/19 | NA | 7/14/28/9 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 8.3 yrs |

| Choi et al. [6] | A | 47 | 36/11 | 54.7 | 3/25/2/3 | NA | 2.38/Nurick | 1.6/Nurick | NA | 16 mos |

| Chiba et al. [3] | P | 53 | 42/11 | 56 | NA | NA | 8.3/JOA | 13.5 | 63.37 | 14.3 yrs |

| Iwasaki et al. [15] | A | 27 | 15/12 | 58 | 14/2/7/4 | NA | 9.5/JOA | 13.2 | 57 | 6 yrs |

| Iwasaki et al. [14] | P | 66 | 51/15 | 57 | 20/7/36/3 54/12 (plateau/hill-shaped) | NA | 9.2/JOA | 13.7/JOA | 55 | 10.2 yrs |

| Masaki et al. [21] | P | 40 | 30/10 | 62.6 | NA | 50 mos | 8.6/JOA | 13.0 | 52.5 | ≥1 yrs |

A anterior approach surgery, P posterior approach surgery, M/F male/female, C/S/M/O continuous/segmental/mixed/other, Neuro neurology, FU follow-up, NA not available, mos months, yrs years, u upper extremity, l lower extremity

Recovery rate (%) = [post-operative JOA score – pre-operative JOA score]/[17 – pre-operative JOA score] × 100

Table 2.

Summary of results on the statistic evaluation of the correlation between clinical factors and surgical outcome

| Author and Year | Surgical approach | Age | Sex | Pre-operative symptom duration | Pre-operative neurological score | Post- or pre-operative radiographic assessment | OPLL type | Other factors | Statistic test |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Koyanagi et al. [20] | A, P | No | NA | Yes | No/JOA | Compression rate—no, Transverse area—yes | NA | NA | Multiple regression analysis |

| Okada et al. [30] | A, P | NA | NA | Yes | NA | IMHSI, Transverse area—yes | NA | NA | Multiple regression analysis |

| Goto et al. [10] | A | NA | NA | NA | NA | Cervical alignment—yes | NA | Progression of ossification, progression of kyphotic deformity, incomplete decompression, long-range fusion —yes, | Mann-Whitney U test |

| Inoue et al. [12] | P | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | Progression of ossification, progression of kyphotic deformity, incomplete decompression, scar formation—yes | Mann-Whitney U test |

| Nakamura and Fujimura, 1998 [9, 26] | A, P | Yes | NA | Yes | No/JOA | IMHSI, ROM—yes, spinal canal expansion, changes of the curve indices—no | NA | Trauma history, progression of ossification—yes | Mann-Whitney U test, Multiple regression analysis |

| Kato et al. [16] | P | Yes | NA | No | Yes/JOA | Occupying rate, SAC—no | No | Trauma, OLF—yes, Surgical level, progression of kyphotic deformity, progression of ossification—no | Multivariate stepwise regression analysis |

| Onari et al. [32] | A | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | Progression of kyphotic deformity, progression of ossification—yes | NA |

| Seichi et al. [33] | P | NA | NA | NA | NA | Change in ROM—yes | NA | Progression of ossification—no, OLF, trauma—yes |

NA |

| Matsuoka et al. [24] | A | No | NA | Yes | Yes/JOA | SAC, Occupying rate, ossification thickness—no, transverse area—yes | No | Involved interspaces—no, progression of ossification—yes | Spearman’s rank correlation, Kruskal-Wallis rank test. |

| Iwasaki et al. [13] | P | Yes | No | NA | Yes/JOA | Occupying ration, SAC, change of the cervical alignment—no | No | Progression of kyphotic deformity, post-operative spontaneous fusion, progression of ossification—no | Multivariate stepwise analysis |

| Ogawa et al. [27, 28] | P | Yes | NA | Yes | Yes | Cervical range of motion—yes, Change of cervical alignment, expansion of spinal canal—no | Yes | NA | Mann-Whitney U test, |

| Uchida et al. [36] | A, P | No | No | No | Yes/JOA | IMHSI—no, Compression rate, occupying ratio, expansion of spinal canal (≥40%), increase area of spinal cord (≥40%)—yes | Yes | Involved interspaces, progression of ossification, Progression of kyphotic deformity—no, SCEP—yes | Multivariate analysis multiple regression analysis |

| Choi et al. [6] | A | No | No | No | No/Nurick | SEA, occupying ratio (CT), Pavlov ratio, double-layer sign—no | No | DM—yes | Univariate analysis, Multiple logistic regression analysis |

| Chiba et al. [3] | P | NA | NA | NA | NA | Cervical alignment—yes, decrease of ROM—no | NA | Progression of ossification—no | Unpaired t test |

| Iwasaki et al. [15] | A | NA | NA | NA | NA | Occupying ratio (≥60%), change in cervical alignment—no | No | OLF, progression of ossification—yes | Mann-Whitney U test. |

| Iwasaki et al. [14] | P | Yes | NA | NA | Yes/JOA | Cervical alignment, occupying ratio (<60%), SAC—no, change in cervical alignment—yes | Yes | NA | Multiple logistic regression |

| Masaki et al. [21] | P | Yes | NA | Yes | No/JOA | Occupation ratio (CT)—no, Change in ROM, change in C2–C7 angle—yes | NA | NA | Mann-Whitney U test |

no no statistically significant correlation (either positive or negative) exists between factor and outcome, yes statistically significant correlation (either positive or negative) exists between factor and outcome, Transverse area transverse area of spinal cord (MRI), Compression rate ratio of flatten of spinal cord caused by compression (MRI), IMHSI intramedullary high signal intensity in T2-weighted, SAC space available for spinal cord in lateral view (X-ray) at the maximum compression level, Occupying rate thickness of ossification/AP at the maximum compression level, Occupying rate (CT) area of ossification/transverse area of spinal canal at the maximum compression level, Low T1 low intensity signal in T1-weighted (MRI), SEA snake-eye appearance, ROM range of motion, SCEP spinal cord evoked potentials, DM diabetes, OLF ossification of ligament flavum

Table 3.

Distribution of number of studies confirming or not confirming the correlation between clinical factors and surgical outcome

| Age | Sex | OPLL type | Duration of symptom | Pre-operative neurological score | SCEP | Trauma | DM | Surgical or Involved level | Incomplete decompression | Progression of OPLL | Onset of OLF | Thickness of OPLL | SAC | Pavlov ratio | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive studies | 6 | 0 | 3 | 6 | 6 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 5 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| p − A + P | 1 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| p – A | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| p – P | 5 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Negative studies | 4 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 1 |

| n − A + P | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| n – A | 2 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| n – P | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| Total studies | 10 | 3 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 5 | 2 | 10 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 1 |

| Compression rate | Transverse area | Occupying ratio (X-ray/CT) | Pre-operative cervical alignment or C2–C7 angle or kyphotic deformity | Post-operative cervical alignment or C2–C7 angle or kyphotic deformity | Pre-operative ROM | Post-operative ROM | Double-layer sign | SEA | IMHSI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive studies | 1 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| p − A + P | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| p – A | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| p − P | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Negative studies | 1 | 0 | 6 | 1 | 6 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| n − A + P | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| n – A | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| n – P | 0 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total studies | 2 | 3 | 7 | 3 | 11 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 3 |

Positive studies: number of studies in which the correlation between clinical factors and surgical outcome was confirmed

p − A + P: number of positive studies in which anterior or posterior approach was used in all cases

p − A: number of positive studies in which anterior approach alone was used in all cases

p − P: number of positive studies in which posterior approach alone was used in all cases

Negative studies: number of studies in which the correlation between clinical factors and surgical outcome was not confirmed

n − A + P: number of negative studies in which anterior or posterior approach was used in all cases

n − A: number of negative studies in which anterior approach alone was used in all cases

n − P: number of negative studies in which posterior approach alone was used in all cases

Total studies: number of studies in which the clinical factors was statistically evaluated

Age

The mean age at the time of surgery ranged from 51.3 to 62.6 years (Table 1). Noticeably, in studies only employing the single posterior or anterior approach in all cases, most (five of the six) studies utilizing the posterior approach without fusion confirmed that older age was a predictive factor for poor outcome. However, studies (two studies) utilizing the anterior approach did not confirm age as a predictor. In addition, the study employing the posterior approach with the lateral mass plate also drew the same conclusion (Table 3).

Sex

A male preponderance was evident in most studies and the male/female ratio ranged from approximately 1.25:1 to 5.3:1 (Table 2). None of the studies found a correlation between the patient’s sex and outcome (Table 3).

Ossification type

The classification of the Investigative Committee on the OPLL of the Japanese Ministry of Public Health and Welfare [35] was used in most of these studies. This classification, based on a lateral view of radiography, divides the ossification into four models: continuous, segmental, mixed and other types (localized or circumscribed type). Among them, mixed type was most common in studies (Table 1). Two of eight studies confirmed the segmental ossification as a predictor for poor outcome. Moreover, some authors [14, 15] divided OPLL as plateau- or hill-shaped ossification, according to a lateral view of radiography, and suggested that hill-shaped ossification was predictive of poor outcome after laminoplasty.

Duration of pre-operative symptoms

The mean pre-operative duration of symptoms ranged from 16.9 to 50 months. Although our understanding is that the shorter the duration of symptoms the better the outcome, it was not confirmed in 33.3% of the studies (Table 3).

Involved interspaces, surgical level and related factors

All five studies showed that the surgical level had no correlation with the operative outcome. Incomplete decompression in surgery led to late deterioration in neurological function.

Spinal cord evoked potentials (SCEPs)

Only one study [36] focused on and confirmed the relation between wave change, decrease in conduction velocity and localized-lesions diagnosed by SCEPs and the outcome of surgery regardless of surgical methods.

Diabetes

Only one study observed and confirmed the correlation between diabetes and surgical outcome of OPLL [18].

Pre-operative neurological score

Three neurological scoring systems were used in these literatures: the JOA score (or the modified JOA score), the Nurick Scale score. The JOA score system was used in most of the studies. The mean range of the pre-operative neurological score was 7.5–9.7, based on the JOA score, and 2.38 by the Nurick Scale score. Six of the eleven studies evaluating the pre-operative neurological score as a predictor confirmed the correlation between the neurological score and the surgical outcome (Table 3).

Radiographic assessments

Radiographic examinations include plain radiography, computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (Table 3). According to their clinical significance, those measurements can be classified in four categories as follows: (1) those reflecting the condition of space in the spinal canal or severity of compression by OPLL, such as the occupying ration of OPLL, space available for the spinal cord (SAC), Pavlov ratio, ossified mass thickness, the cord’s compression ratio, double-layer sign (CT), pre- or post-operative traverse area of the cord and expansion of the spinal canal, (2) those reflecting cervical alignment, such as pre- and pro-operative cervical alignment, C2–C7 angle and progression of kyphosis deformity, (3) pre- and pro-operative segmental range of motion in the cervical spine (ROM), (4) those reflecting change inside of the cord, such as intra-medullar high signal intensity (IMHSI) and snake-eye appearance (SEA).

In the first category, only the transverse area of the cord (including the post-operative transverse area of the cord) was thought of as a predictor for surgical outcome in all three studies involved. In the second category, apart from the progression of kyphosis being inconclusive, others had no relationship with the surgical outcome. In the third category, studies found that not the decrease but the increase of post-operative ROM was closely related to the surgical outcome. In the last category, intra-medullar high signal intensity (IMHSI) was confirmed as predictor in two of three studies involved and SEA was not thought as predictor in one studies involved (Table 3).

History of trauma

All three pieces of literature showed a history of trauma as a factor affecting the clinical outcome.

Progression of OPLL or onset of ossification of the ligament flavum (OLF) in the thoracic spine

There was a great debate regarding the results of the relation of progression of OPLL with deterioration in the long-term outcome because five of eleven studies did not confirm the relationship. However, the onset of OLF in the thoracic spine was regarded as the cause of deterioration in the long-term surgical outcome in all three studies involved.

Discussion

Although OPLL is very common in Asian countries, it is currently attracting extensive attention from the world, especially from Western countries. Moreover, most of the authors in the literature were Japanese. Therefore the English-language literature can sufficiently reflect the status of surgical management of cervical OPLL up to now. However, there are some limitations in the present study as following: (1) Ideally, each of the studies included should consist of large numbers of cases and have a similar design, and, therefore meta-analysis could be performed to determine what the predictors for the surgical outcome of cervical OPLL are. However, all the literature was retrospective studies and constitutes a low level of scientific evidence. Due to the variability in neurological scoring systems or in statistic analysis, and the lack of some basic data, it is difficult to use meta-analysis to re-evaluate the literature. Because of the variability between the various study groups regarding surgical methods, patient sample, surgical techniques of chief surgeons, focused related factors, evaluation criteria, follow-up period, and statistics, etc., it is very difficult to draw a clear conclusion from the mixed data about the prognostic factors for the surgical outcome of cervical OPLL, (2) Furthermore, given possible publication bias, if a relevant report was not included, conclusions may be biased. The possibility of missing data also might result in system error in the research. Although thus, we think that by deeply examining all the studies involved, some significant conclusions could be reached. The results do represent a certain trend. Indeed, the presence or absence of statistical correlation between factors and outcome shown in Table 2 is not meant which are best or worst studies and our objectives were not to establish therapeutic standards or guidelines. To our best knowledge, the present review is the first review of predictors for the surgical outcome of cervical OPLL.

According to the results, the factors could be classified in three categories: (1) the factors, confirmed as predictors for surgical outcome by all or most of the studies involved, including the traverse area of the spinal cord, age, SCEPs, increase of ROM, diabetes, history of trauma, onset of OLF in the thoracic spine and incomplete decompression, (2) the factors, not confirmed as predictors by all or most of the studies involved, including sex, occupying ratio of OPLL, SAC, Pavlov ratio, ossified mass thickness, compression ratio, C2–C7 angle, cervical alignment, involved interspaces and surgical levels, double-layer sign and SEA, (3) controversial factors include the neurological score, OPLL type, pre-operative duration of symptoms, IMHSI and progression of OPLL or kyphosis and expansion of the spinal canal.

Factors confirmed as predictors

It seems that age at surgery is related to the surgical outcome of the posterior approach rather than the anterior approach. Two possible explanations may clarify the results: (1) Posterior procedure without instrumentation fusion preserves the segmental motion of the cervical spine, while an increase in the segmental motion, which may be the consequence of progressive atrophy of the nuchal muscles, was thought as a deteriorating factor for the outcome [9, 21, 26]. Thus, increase in segmental motion may lead the deterioration outcome in the older patients after the posterior approach. However, laminectomy with instrumented fusion has rarely been performed in Japan as a treatment of OPLL and no long-term outcome data are available. (2) Posterior surgery is mainly for high-risk patients over 65 years of age. Some investigators [9, 16] observed that age at the time of surgery significantly influences the outcome at the first 5 years rather than at 3 years after surgery for OPLL. Therefore, the elderly recipients of posterior surgery are more vulnerable to normal aging processes in neural and skeletal functions than younger patients who receive the anterior surgical procedure. In addition, it is impossible to rule out the influence of age-related changes on the long-term results by current measurement tools, such as the JOA scoring system, so a novel evaluation system allowing for the elimination of age influence may be necessary to assess the true effect of surgery on neurological functions, especially in long-term follow-up studies [3].

Among the imaging measurements, the transverse area of the spinal cord was indicated not only by the anterior-posterior diameter but also width. Thus the reduced transverse area of the cord reflects not only the severity of the spinal cord compression but also the spinal cord atrophy caused by chronic compression [20, 30]. A cadaveric study [29] of spondylotic myelopathy indicated that the morphologic changes of the cord were related to pathologic severity which also is considered to be significantly related to the functional recuperation. Therefore, it is well understood that the transverse area of the spinal cord correlates well with the recovery rate. With regard to ROM, the decrease in ROM did not affect neurological recovery but had related to the axial symptoms in cervical spine after operation. Modifying the range of laminar expansion and post-operative treatment would improve the discomforts [3, 33]. Otherwise, because the degenerated spinal cord is losing elasticity it would become vulnerable to greater dynamic stress. The increase in ROM may lead to greater dysfunction of the degenerated spinal cord, which even withstands long-lasting OPLL-induced compression [21].

IMHSI in T2-weighted MRI are frequently seen in patients with cervical compressive myelopathy. It includes a broad spectrum of compressive myelomalacic pathology from edema to syrinx formation and reflects a broad spectrum of spinal cord recuperative potentials [2, 7, 25]. Accordingly, it cannot accurately predict the prognosis and the results regarding its role in prognosticating the surgical outcome of OPLL were conflicting [36]. SEA, another multilevel IMHSI, which refers to two small high signal intensity spots of the cord depicted on axial T2-weighted MRI, is a product of cystic necrosis resulting from mechanical compression and venous infarction. Whereas the two pathologic changes have different prognosis after surgical interference: unlike cystic necrosis in the cord being irrecoverable, venous infarction may be progressive and ongoing and decompression surgery may halt further deterioration and provide a chance of improvement [6, 8]. Therefore, the difference theoretically makes it difficult to determine if SEA is a predictor. By reviewing literatures, we found that there is only one study noting the relation between SEA and surgical outcome and not confirming the relation.

It is already known that diabetes not only involves peripheral nerves but also affects the spinal cord [7, 34]. Consequently, compared to the patients without diabetes, the patients with diabetes experienced poor recovery in neurological function after the cervical operation. Moreover, diabetes also has the direct relationship with OPLL. Firstly, diabetes was confirmed as an independent risk factor for the onset of OPLL [31]. Secondly, abnormal insulin secretory response, seen in the early stage of non-insulin-dependent diabetes (NIDDM), is positively associated with the extent of OPLL [1]. A recent in vitro study testified to the correlation between glycation end products, the typical characteristics of NIDDM, and the ossification ligament [37]. Hence, although the relation of diabetes with surgery of OPLL was proved by only one study, it should cause surgeons to be more attentive to whether or not their patients have a history of diabetes.

Factors not confirmed as predictors

Most of the measurements reflecting the condition of space in the spinal canal were not predictive factors for the outcome in cervical OPLL [6, 13, 16, 19, 21, 24]. They only predicted some dilemmas encountered by surgeons during surgery of OPLL, such as dural penetration by OPLL. Because of the advances in microsurgical techniques, catastrophic events during surgery in such cases were reduced greatly and these measurements could not predict the surgical outcome [6]. Other measurements also reflect some pathological characteristics of a compressed spinal cord. In one report [22], SAC of less than 6 mm was thought as a critical point above which the ossification foci, static factor, is the most significant factor inducing myelopathy, whereas below that point, dynamic factors, such as ROM of the cervical spine, may be largely involved in inducing myelopathy. Therefore these measurements also had no direct relationship with the surgical outcome.

Controversial factors

There may not be a correlation between the duration of symptoms and the outcome if the majority of patients have an advanced-stage disease because of diagnostic delay and irreversible cord damage that has already occurred. However, something may have been neglected. The duration of pre-operative symptoms actually reflects the length of time when myelopathy arises and aggravates for the sake of chronic compression by ossified mass. Other factors were also associated significantly with the onset and aggravation of myelopathy [22, 23]: circulatory factors; such as diabetes, hypertension and angina pectoris; trauma, progression of the ossification, and the dynamic factor, such as the motion range of the cervical spine. All these factors can act to influence myelopathy in the duration of pre-operative symptoms while they could not be reflected by the length of the duration of pre-operative symptoms. If these factors act in short during this time to cause severe or irreversible myelopathy, surgical intervention would not make a significant difference in such a situation and there would not be a correlation between the duration of symptoms and the surgical outcome. Consequently, despite the inconclusive outcome, almost all authors recommend early surgery rather than observation in patients with mild to moderate symptoms, especially for the elderly patients, for fear of encountering those unexpected factors.

The JOA score was devised for patients with cervical myelopathy and provides a semi-quantitative assessment of functions by evaluating the ability to eat, ambulate, and void. When using the recovery rate, which is calculated as follows: recovery rate = (post-operative JOA score – pre-operative JOA score)/(17 – pre-operative score), comparison of the degree of functional recovery among individual patients and among different studies is possible [11]. The Nurick scale focuses on ambulation ability. Surprisingly, our assumption that the better the pre-operative score, the better the surgical outcome seems to be true only in 54.5% of the studies. There is not a significant difference in data analyses between studies confirming the pre-operative score as predictor and studies not confirming it. Actually, the great majority of patients with a high pre-operative score recover quite well after surgery. Whereas the presence of some patients with a low pre-operative score obtained “unexpectedly” good recovery after surgery may be responsible for the lack of correlation. Alternatively, the limitation of the scoring system itself may weaken its prognosis effect. All of these scoring systems only reflect the severity of myelopathy but not the cause contributing to the myelopathy. Therefore, if the pathological features are entirely compressive, decompressive surgery will resolve them and will always be effective. If myelopathy is the result of a combination of factors; such as compression, ischemia, and demyelization in patients with the same neurological score; the decompressive surgery will not resolve all of the causes and will not be so effective. The noncompressive factors could also be progressive and could lead to the delayed deterioration. That is, the scoring systems could not predict if the surgery might resolve all of the causes to the myelopathy well and also could prognosticate the surgical outcome.

The studies [14, 15, 27], which showed that the ossified type was closely related to the outcome of laminoplasty, actually indicated that the posterior procedure has limitations in maintaining decompression of the spinal cord and stability of the cervical spine. The increase in cervical mobility following laminoplasty at the level of remaining ossification mass may stimulate the maturation of ossification and aggravate the impingement of the ossification mass to the spinal cord [5, 17]. Intervertebral instability accelerates the maturation of ossification, whereas the maturation of ossification partly restores the intervertebral stability [32]. Thus, for non-segmental ossification, the ossification always spans the intervertebral spaces and the maturation of ossification due to the intervertebral stability offset the intervertebral stability. As a result, the impingement of the ossification mass to the spinal cord in the non-segmental ossification is milder than that in the segmental type. That is, the development of myelopathy may be more influenced by dynamic factors in the segmental type of ossification than in mixed and continuous types of ossification. Therefore, surgical fusion or use of the soft cervical collar might be more effective for the patients with the segmental type of OPLL than for those with the continuous mixed type of OPLL [13, 16, 32].

Deterioration of the patient’s neurological condition was an important problem in the evaluation of long-term results. However, the roles of progression of OPLL and kyphosis and the expansion of the spinal canal after surgery in the deteriorated area remain controversial. The progression of OPLL, especially the transverse spread in the residual ossification foci, would recompress the spinal cord [10, 12]. Despite the high progression rate after posterior surgery, less than 10% of patients experienced worsening myelopathy during the follow-up period and most patients who experienced deterioration of the myelopathy had sustained trauma, mostly from a fall, or developed an ossification of the ligament flavum (OLF) at the thoracic spine [16, 28, 33]. Several factors, such as age, ossification type, and the change in ROM of the cervical spine, could influence the progression of ossification foci [5, 17]. On the other hand, in patients with OPLL, the ossified ligaments are likely to hold the vertical height of the cervical spine, thereby maintaining the vertical tensions of the spinal cord and resulting in a greater compression force when the alignment is kyphosis [4]. In face of significant kyphosis, surgeons would always like to choose the anterior approach to remove the ossified mass directly. However, if posterior surgery is performed in such cases, the remaining ossified mass and existing kyphosis could aggravate the compression of the cord [32]. Indeed, the increase in post-operative kyphosis is a deteriorating factor for the posterior approach. The progression of kyphosis or OPLL after surgery would facilitate the recompression, while adequate expansion of the spinal canal by surgery providing the spinal cord with posterior shift space would prevent the recompression. Thus, the three factors have counteractive effects in the influence of long-term results from surgery and it may explain why the predictive role of each factor alone remains controversial.

Conclusions

The clinical factors that could predict the surgical outcome include traverse area of the spinal cord, SCEPs, the increase of ROM, diabetes, history of trauma, onset of OLF in the thoracic spine and incomplete decompression. Age at surgery seems to closely relate to the outcome of a posterior surgical procedure. It is unclear whether the neurological score, OPLL type, the pre-operative duration of symptoms, IMHSI and progression of OPLL or kyphosis and expansion of the spinal canal predict the post-operative outcome due to the great conflicting results among the studies. Other factors, such as sex, involved levels and many imaging measurements, are not likely to predict the operative outcome.

To draw an effective conclusion, the use of uniform neurological score and proper statistical analysis, such as stepwise regression analysis, should be proposed. In addition, it is important to analyze the effect of each variable on groups with different surgical procedures, such as the anterior or posterior approach, as well as patients with different compressive pathology, such as OPLL or cervical spondylotic myelopathy. Extensive researches on pathology of cervical myelopathy due to OPLL and etiology of OPLL would be helpful for exactly understanding these clinical factors and choosing the optimal therapeutic strategy for OPLL.

References

- 1.Akune T, Ogata N, Seichi A, Ohnishi I, Nakamura K, Kawaguchi H. Insulin secretory response is positively associated with the extent of ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament of the spine. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001;83:1537–1544. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200110000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Al-Mefty O, Harkey LH, Middleton TH, Smith RR, Fox JL. Myelopathic cervical spondylotic lesions demonstrated by magnetic resonance imaging. J Neurosurg. 1988;68:217–222. doi: 10.3171/jns.1988.68.2.0217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chiba K, Ogawa Y, Ishii K, Takaishi H, Nakamura M, Maruiwa H, et al. Long-term results of expansive open-door laminoplasty for cervical myelopathy—average 14-year follow-up study. Spine. 2006;31:2998–3005. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000250307.78987.6b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chiba K, Toyama Y, Watanabe M, Maruiwa H, Matsumoto M, Hirabayashi K. Impact of longitudinal distance of the cervical spine on the results of expansive open-door laminoplasty. Spine. 2000;25:2893–2898. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200011150-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chiba K, Yamamoto I, Hirabayashi H, Iwasaki M, Goto H, Yonenobu K, et al. Multicenter study investigating the postoperative progression of ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament in the cervical spine: a new computer-assisted measurement. J Neurosurg Spine. 2005;3:17–23. doi: 10.3171/spi.2005.3.1.0017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Choi S, Lee SH, Lee JY, Choi WG, Choi WC, Choi G, et al. Factors affecting prognosis of patients who underwent corpectomy and fusion for treatment of cervical ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament: analysis of 47 patients. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2005;18:309–314. doi: 10.1097/01.bsd.0000161236.94894.fc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eaton SE, Harris ND, Rajbhandari SM, Greenwood P, Wilkinson ID, Ward JD, et al. Spinal-cord involvement in diabetic peripheral neuropathy. Lancet. 2001;358:35–36. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)05268-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fernandez de Rota JJ, Meschian S, Fernandez de Rota A, Urbano V, Baron M. Cervical spondylotic myelopathy due to chronic compression: the role of signal intensity changes in magnetic resonance images. J Neurosurg Spine. 2007;6:17–22. doi: 10.3171/spi.2007.6.1.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fujimura Y, Nishi Y, Chiba K, Nakamura M, Hirabayashi K. Multiple regression analysis of the factors influencing the results of expansive open-door laminoplasty for cervical myelopathy due to ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 1998;117:471–474. doi: 10.1007/s004020050296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goto S, Kita T. Long-term follow-up evaluation of surgery for ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament. Spine. 1995;20:2247–2256. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199510001-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hirabayashi K, Miyakawa J, Satomi K, Maruyama T, Wakano K. Operative results and postoperative progression of ossification among patients with ossification of cervical posterior longitudinal ligament. Spine. 1981;6:354–364. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198107000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Inoue H, Ohmori K, Ishida Y, Suzuki K, Takatsu T. Long-term follow-up review of suspension laminotomy for cervical compression myelopathy. J Neurosurg. 1996;85:817–823. doi: 10.3171/jns.1996.85.5.0817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iwasaki M, Kawaguchi Y, Kimura T, Yonenobu K. Long-term results of expansive laminoplasty for ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament of the cervical spine: more than 10 years follow up. J Neurosurg. 2002;96(Spine 2):180–189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Iwasaki M, Okuda S, Miyauchi A, Sakaura H, Mukai Y, Yonenobu K, et al. Surgical strategy for cervical myelopathy due to ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament: Part 1: clinical results and limitations of laminoplasty. Spine. 2007;32:647–653. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000257560.91147.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Iwasaki M, Okuda S, Miyauchi A, Sakaura H, Mukai Y, Yonenobu K, et al. Surgical strategy for cervical myelopathy due to ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament: Part 2: advantages of anterior decompression and fusion over laminoplasty. Spine. 2007;32:654–660. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000257566.91177.cb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kato Y, Iwasaki M, Fuji T, Yonenobu K, Ochi T. Long-term follow-up results of laminectomy for cervical myelopathy caused by ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament. J Neurosurg. 1998;89:217–223. doi: 10.3171/jns.1998.89.2.0217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kawaguchi Y, Kanamori M, Ishihara H, Nakamura H, Sugimori K, Tsuji H, et al. Progression of ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament following en bloc cervical laminoplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001;83:1798–1802. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200112000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kawaguchi Y, Oya T, Abe Y, Kanamori M, Ishihara H, Yasuda T, et al. Spinal stenosis due to ossified lumbar lesions. J Neurosurg Spine. 2005;3:262–270. doi: 10.3171/spi.2005.3.4.0262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koyanagi I, Imamura H, Fujimoto S, Hida K, Iwasaki Y, Houkin K. Spinal canal size in ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament of the cervical spine. Surg Neurol. 2004;62:286–291. doi: 10.1016/j.surneu.2003.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koyanagi T, Hirabayashi K, Satomi K, Toyama Y, Fujimura Y. Predictability of operative results of cervical compression myelopathy based on preoperative computed tomographic myelography. Spine. 1993;18:1958–1963. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199310001-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Masaki Y, Yamazaki M, Okawa A, Aramomi M, Hashimoto M, Koda M, et al. An analysis of factors causing poor surgical outcome in patients with cervical myelopathy due to ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament: anterior decompression with spinal fusion versus laminoplasty. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2007;20:7–13. doi: 10.1097/01.bsd.0000211260.28497.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Matsunaga S, Sakou T, Taketomi E, Komiya S. Clinical course of patients with ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament: a minimum 10-year cohort study. J Neurosurg. 2004;100(Spine 3):245–248. doi: 10.3171/spi.2004.100.3.0245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Matsunaga S, Sakou T, Taketomi E, Yamaguchi M, Okano T. The natural course of myelopathy caused by ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament in the cervical spine. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1994;305:168–177. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199408000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Matsuoka T, Yamaura I, Kurosa Y, Nakai O, Shindo S, Shinomiya K. Long-term results of the anterior floating method for cervical myelopathy caused by ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament. Spine. 2001;26:241–248. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200102010-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mehalic TF, Pezzuti RT, Applebaum BI. Magnetic resonance imaging and cervical spondylotic myelopathy. Neurosurgery. 1990;26:217–226. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199002000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nakamura M, Fujimura Y. Magnetic resonance imaging of the spinal cord in cervical ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament. Can it predict surgical outcome? Spine. 1998;23:38–40. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199801010-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ogawa Y, Chiba K, Matsumoto M, Nakamura M, Takaishi H, Hirabayashi H, et al. Long-term results after expansive open-door laminoplasty for the segmental-type of ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament of the cervical spine: a comparison with nonsegmental-type lesions. J Neurosurg Spine. 2005;3:198–204. doi: 10.3171/spi.2005.3.3.0198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ogawa Y, Toyama Y, Chiba K, Matsumoto M, Nakamura M, Takaishi H, et al. Long-term results of expansive open-door laminoplasty for ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament of the cervical spine. J Neurosurg Spine. 2004;1:168–174. doi: 10.3171/spi.2004.1.2.0168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ohshio I, Hatayama A, Kaneda K, Takahara M, Nagashima K. Correlation between histopathologic features and magnetic resonance images of spinal cord lesions. Spine. 1993;18:1140–1149. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199307000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Okada Y, Ikata T, Yamada H, Sakamoto R, Katoh S. Magnetic resonance imaging study on the results of surgery for cervical compression myelopathy. Spine. 1993;18:2024–2029. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199310001-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Okamoto K, Kobashi G, Washio M, Sasaki S, Yokoyama T, Miyake Y, Sakamoto N, Ohta K, Inaba Y, Tanaka H, Japan Collaborative Epidemiological Study Group for Evaluation of Ossification of the Posterior Longitudinal Ligament of the Spine (OPLL) Risk Dietary habits and risk of ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligaments of the spine (OPLL); findings from a case-control study in Japan. J Bone Miner Metab. 2004;22:612–617. doi: 10.1007/s00774-004-0531-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Onari K, Akiyama N, Kondo S, Toguchi A, Mihara H, Tsuchiya T. Long-term follow-up results of anterior interbody fusion applied for cervical myelopathy due to ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament. Spine. 2001;26:488–493. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200103010-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Seichi A, Takeshita K, Ohishi I, Kawaguchi H, Akune T, Anamizu Y, et al. Long-term results of double-door laminoplasty for cervical stenotic myelopathy. Spine. 2001;26:479–487. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200103010-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Slager UT. Diabetic myelopathy. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1978;102:467–469. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tsuyama N. Ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament of the spine. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1984;184:71–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Uchida K, Nakajima H, Sato R, Kokubo Y, Yayama T, Kobayashi S, et al. Multivariate analysis of the neurological outcome of surgery for cervical compressive myelopathy. J Orthop Sci. 2005;10:564–573. doi: 10.1007/s00776-005-0953-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yokosuka K, Park JS, Jimbo K, Yoshida T, Yamada K, Sato K, et al. Immunohistochemical demonstration of advanced glycation end products and the effects of advanced glycation end products in ossified ligament tissues in vitro. Spine. 2007;15:337–339. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000263417.17526.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]