Abstract

The AIDS epidemic caused unexpected worldwide levels of tuberculosis, even in developed countries where the incidence used to be low. Patients with urogenital tuberculosis in developed countries have fewer specific symptoms and lower rates of delayed diagnoses compared with patients from other countries. As a result, the disease tends to be less serious, with more patients presenting without significant lesions of the upper urinary tract on diagnosis. These data point to a correlation of the timing of diagnosis with the severity of urogenital tuberculosis. A systematic search for urogenital tuberculosis, regardless of symptoms, is warranted for early detection.

Key words: Tuberculosis, urogenital; Tuberculosis, renal; Male genital tuberculosis; Nephrectomy; Urinary bladder, surgery; Cystitis

Tuberculosis is the leading cause of morbidity and mortality due to infectious diseases worldwide, with 8 to 10 million new cases and 1.9 to 3 million deaths each year. In developing countries, there is an annual incidence of 100 to 450 new cases per 100,000 inhabitants, with 2 to 3 million deaths per year, and 75% of cases affect people between 15 and 50 years of age. Conversely, developed countries have a lower incidence, with 7 to 15 new cases per 100,000 inhabitants and 40,000 deaths per year.1,2 In developed countries the elderly, ethnic minorities, and immigrants are chiefly affected.3,4

The introduction of pharmacologic treatment saw a decline in the incidence of tuberculosis of 12% per year, with predictions of possible eradication.1 There were 21,000 new cases and 2000 deaths due to tuberculosis in 1984 in the United States, contrasting with 84,000 new cases and 20,000 deaths in 1953.5 Nevertheless, tuberculosis incidence rates stabilized in most of the world, with increases in African countries and Eastern Europe in recent decades.2 This tuberculosis recrudescence was caused by the AIDS pandemic, emergence of resistant bacilli, human migration patterns, and world poverty.2,6 The AIDS epidemic caused unexpected levels of tuberculosis worldwide, even in developed countries where the incidence used to be low. Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection can easily reactivate latent foci, provoke rapid progress in acquired tuberculosis infection, and make possible an exogenous re-infection.7 Among HIV-infected people worldwide, 25% to 50% have active tuberculosis.8 A study published in 2000 showed that 46% of 1282 tuberculosis patients in an inner-city hospital in the United States had AIDS.9 In addition, AIDS-related immunosuppression increases the risk of bacillemia and of extra-pulmonary manifestations of the disease.10

Extrapulmonary sites account for 10% of tuberculosis cases. Urogenital tuberculosis, responsible for 30% to 40% of all extrapulmonary cases, is second only to lymph-node involvement.1,6,11,12 Urogenital tuberculosis also occurs in 2% to 20% of patients with pulmonary tuberculosis.11,13–16 In developed countries urogenital tuberculosis occurs in 2% to 10% of cases of pulmonary tuberculosis; in developing countries these figures rise to 15% to 20%.11,14–16

Etiopathogeny

Mycobacterium tuberculosis, an acid-fast aerobic bacillus, is the most virulent mycobacterium pathogen to the human species. Its slow replication rate accounts for the insidious nature of the infection and the resistance to ordinary antibiotics, because the latter work during bacterial division. Although the bacillus can stay dormant and not produce symptoms for a long time, reactivation may follow a decrease in immunity.1

Once inhaled, the bacilli multiply in the pulmonary alveoli with primary granuloma formation. As few as 1 to 5 bacilli in the alveolus may result in infection. Primary pulmonary tuberculosis is usually clinically silent and self-limited. From this pulmonary focus, bacillemia leads to bacillus implantation in other organs. At this point, colonization of the renal and prostate parenchyma may occur. After 6 months, spontaneous cicatrization of primary pulmonary tuberculosis occurs and the patient enters a latent phase, with 5% likelihood of disease reactivation in the following 2 years and 5% likelihood of lifetime reactivation. In most active cases of both pulmonary and extrapulmonary disease, latent foci were reactivated after a decrease in immunity brought about by malnutrition, diabetes mellitus, steroid use, immunosuppressant use, and immunodeficiency.2

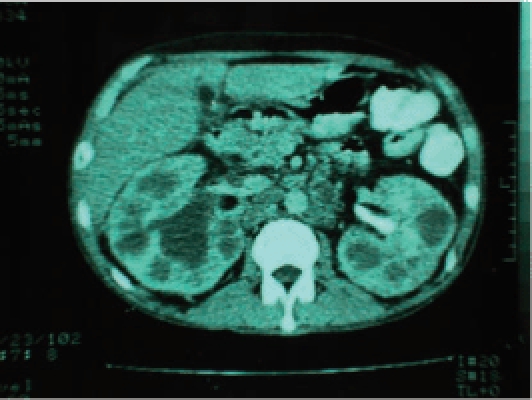

Renal lesions, initially bilateral, cortical, glomerular, and pericapillary, are typical of hematogenic spread and are concomitant with other hematogenic foci in the prostate and other organs beyond the urogenital system.17,18 These foci generally cicatrize and a latent period ensues, unless there is immunodeficiency and systemically symptomatic miliary tuberculosis develops.2,15 Of patients with miliary tuberculosis, 25% to 62% have renal lesions with multiple bilateral foci (Figure 1).17

Figure 1.

Tomography showing multiple and bilateral kidney lesions in a patient with AIDS and miliary tuberculosis.

The latent period between pulmonary infection and clinical urogenital tuberculosis is 22 years on average, ranging from 1 to 46 years according to the moment when immunity decreases and the latent renal or prostate foci are reactivated.14 After reactivation of the renal foci, infection progresses from a single focus, affecting 1 kidney and sparing the other.18 This accounts for the greater frequency of unilateral renal tuberculosis.14,19 Contiguous involvement of the urinary collecting system leads to bacilluria and ureter, bladder, and genital organ infection.17,20

Affected Organs

Tuberculosis may affect the whole male urinary and genital tract. Table 1 shows the frequency of male urinary and genital tract impairment.14,19,21

Table 1.

Frequency of Tuberculosis-Affected Urogenital Organs

| Christensen, 197414 (United States) | García-Rodríguez et al, 199419 (Spain) | Mochalova and Starikov, 199721 (Russia) | |

| Total (N) | 102 | 81 | 4298 |

| Men (n) | 72 | 51 | 2888 |

| Kidney | 60.8 | 93.8 | 100 |

| Bilateral | 29 | 14.5 | 83.4 |

| Unilateral | 71 | 85.5 | 16.6 |

| Ureter | 18.6 | 40.7 | NR |

| Bladder | 15.7 | 21 | 10.6 |

| Prostate* | 26.4 | 2 | 49.5 |

| Epididymis* | 22.2 | 11.8 | 55.5 |

| Seminal vesicles | 6.9 | 0 | NR |

| Urethra | 1.4 | 2 | 21.4 |

Values are percentages unless otherwise noted.

In relation to male patients.

NR, not reported.

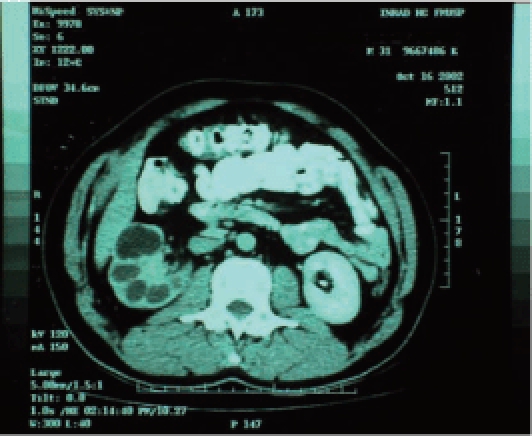

Urogenital tuberculosis most frequently affects the kidneys. Renal infection is slowly progressive, asymptomatic, and highly destructive, with instances of unilateral renal exclusion and renal failure on diagnosis.22 Kidney destruction may be due to progression of a focal lesion, with caseous granuloma formation, fibrosis, and renal cavitations, or more frequently, obstruction of the urinary collecting system23–25 (Figure 2). The latter may be distal when due to ureteral stenosis or proximal when there are intrarenal stenoses.12

Figure 2.

Tomography showing unilateral renal tuberculosis with low-functioning kidney with dilatation of the excretory system.

Ureteral and bladder tuberculosis is secondary to descending infection through the urinary collecting system. Descending lymphatic spread is also possible: an experimental study demonstrated ureteral tuberculosis in kidney-inoculated pigs with total ureter occlusion.26 In ureteral tuberculosis, multiple stenoses develop throughout the ureter, with predominance in the vesicoureteral junction.6,22 Ureteral stenosis is the main cause of renal exclusion in tuberculosis, occurring in up to 93.7% of cases.6 In bladder tuberculosis there is an acute inflammatory process with hyperemia, ulceration, and tubercle formation in the vicinity of the ureteral meatus, with subsequent fibrosis of the bladder wall.1,22

Despite constant urethral exposure to the urinary bacilli, urethral tuberculosis occurs in only 1.9% to 4.5% of all cases of urogenital tuberculosis and never as an isolated entity. Acute urethritis with associated prostate tuberculosis or urethral stenosis and fistulae are the common clinical presentations.27,28

Tuberculosis affects the whole male genital tract, with lesions in the prostate, seminal vesicles, deferent ducts, epididymides, Cooper glands, penis, and testicles, the latter through contiguity with the epididymides, because the blood-testicle barrier plays a protective role. Genital tuberculosis occurs through hematogenic spread to the prostate and epididymides or through the urinary system to the prostate and canalicular spread to the seminal vesicles, deferent ducts, and epididymides.29,30 Genital tuberculosis may be accompanied by renal lesions, but it may present in isolation.31

In prostate contamination, hematogenic spread is more frequent than through the urinary system.32 In an experimental and clinical observational study, bacillus injection in the subcapsular and intracortical renal regions of rabbits was observed to lead to tuberculosis prostate foci concomitant with foci in other organs and discrete renal foci without communication with the urinary system. In clinical cases the prostate lesion was not accompanied by mucosal or submucosal impairment of the prostatic urethra, being situated instead in the lateral and peripheral regions, whereas urethral ulcerative lesions with prostate involvement were only seen in more advanced cases.32 In prostate tuberculosis there is caseous necrosis with calcification and development of fibrosis with gland hardening.33 Prostate tuberculosis is usually asymptomatic and diagnosed as an incidental prostatectomy finding in patients older than those with urogenital tuberculosis.33–35 Prostate abscesses are rare but occur in AIDS patients with urogenital tuberculosis.36

The epididymides are affected in 10% to 55% of men with urogenital tuberculosis, and scrotal changes are the main sign on physical examination.14,19,21,37 Epididymal tuberculosis is bilateral in 34% of cases, presenting as a nodule or scrotal hardening in all patients, scrotal fistula in half of cases, and hydrocele in only 5%.38

Because of canalicular obstruction with oligoazoospermia and low-volume ejaculate due to obstruction of the ejaculatory ducts, infertility may be the first symptom of tuberculosis. Multiple stenoses in the canalicular system make reconstruction impossible and are an indication for assisted reproduction.6,30,39 Leukospermia is a less frequent and earlier mechanism underlying tuberculosis-related infertility.30

Penile tuberculosis is rare, developing after direct sexual contact or secondary to another urogenital focus with the appearance of an erythematous papule that may ulcerate. Infiltration of the cavernous bodies may lead to penis deformity and urethral fistulae, a situation that may be confused with a penile cancer.40,41

Clinical Features

Table 2 shows the clinical features of 8961 patients described in 33 series of urogenital tuberculosis.9,12,14–16,18,19,21,31,42–65

Table 2.

Comparison Between 3036 Cases of Urogenital Tuberculosis From Developed Countries and 5925 Cases From Other Countries

| Variable | Developed Countries | Other Countries | P Value* | Total |

| Total (N) | 3036 | 5925 | 8961 | |

| Men | 62.9 | 65.4 | .02 | 64.9 |

| Women | 37.1 | 34.6 | .02 | 35.1 |

| Age (years), median (range) | 42.6 (7–88) | 39.2 (5–83) | 40.7 (5–88) | |

| Previous tuberculosis | 37.9 | 38.4 | .66 | 36.5 |

| Symptoms and signs | ||||

| Storage symptoms | 44.2 | 55.2 | <.01 | 50.5 |

| Dysuria | 33.8 | 46.4 | <.01 | 37.9 |

| Lumbar pain | 28.8 | 42.3 | <.01 | 34.4 |

| Hematuria | 24.5 | 44.3 | <.01 | 35.6 |

| Epididymis lesion† | 20.6 | 47.4 | <.01 | 48.9 |

| Fever and malaise | 23.2 | 19.9 | .28 | 21.9 |

| No symptoms | 8.4 | 0 | <.01 | 6.4 |

| Renal failure | 1.4 | 10.2 | <.01 | 5.7 |

| Diagnosis | ||||

| Urine | 79.0 | 55.4 | <.01 | 64.2 |

| Histopathology | 7.8 | 38.3 | <.01 | 21.9 |

| Clinicoradiographic | 9.6 | 11.3 | .36 | 10.4 |

| Kidney | ||||

| Unilateral nonfunctioning | 22.8 | 33.1 | <.01 | 26.9 |

| Normal | 18.8 | 13.2 | <.01 | 15.2 |

| Contracted bladder | 4.0 | 11.6 | <.01 | 8.9 |

| Surgeries | 56.6 | 53.6 | <.01 | 54.9 |

| Ablative | 35.0 | 26.9 | <.01 | 27.2 |

| Nephrectomy | 27.9 | 26.0 | .37 | 27.6 |

Developed countries included the United States, Japan, and those in Europe. Other countries included Russia and those in Latin America and Africa.

Values are percentages unless otherwise noted.

Comparison between developed countries and other countries (χ2 test).

In relation to male patients.

Urogenital tuberculosis affects more men than women (2:1), with a mean age of 40.7 years (range, 5–88 years). Only 36.5% of patients have a previous diagnosis of tuberculosis or evidence from imaging. Thus, when urogenital tuberculosis is suspected, this suspicion cannot generally be sustained only by a previous history of pulmonary disease. Symptoms arise when there is bladder impairment: where tuberculosis is concerned, the kidneys are mute and the bladder plays the role of the vocal cords.16,43 Storage symptoms, dysuria, and hematuria are thus the most common presentation, affecting 50.5%, 37.9%, and 35.6% of cases, respectively. On physical examination, up to 48.9% of men have some scrotal abnormality, with a lump, epididymal hardening, or fistula as important signs (Table 2).

Only 50% of patients with renal tuberculosis in autopsy studies were symptomatic, with only 18% having received a clinical diagnosis.17 The delayed diagnosis is due to the insidious progression, paucity or non-specificity of symptoms, lack of physician awareness, and poor care-seeking behavior.12,13 Therefore, diagnosis is rarely made before severe urogenital lesions develop.30 Of patients with urogenital tuberculosis, 5.7% develop end-stage chronic renal failure (Table 2).

The χ2 test was used for a comparison between developed countries and others, with a P value of .05 considered statistically significant. Patients from developed countries are less likely to have specific symptoms and to receive histologic diagnoses, a situation that points to earlier diagnosis. In such countries, tuberculosis is consequently less severe, with a lower frequency of renal failure, unilateral renal exclusion, and contracted bladder, and a higher frequency of normal upper urinary systems (Table 2). These data underscore the relationship between the severity of urogenital tuberculosis and the timing of the diagnosis.

Patients with urogenital tuberculosis and AIDS are younger than those without AIDS but present the same symptoms and signs and the same mortality rates.9 Nevertheless, AIDS patients are more prone to kidney and prostate abscesses.36,66

Although urogenital tuberculosis affects patients of all ages, there are few cases in children because of the long interval between pulmonary infection and renal tuberculosis.14,29,43,67 Recurrent urinary infection or urinary infection that does not respond to conventional antibiotics, pyuria with negative urine cultures, hematuria, and orchiepididymitis are suggestive findings in the pediatric population.67

Laboratory and Radiologic Workup

Identification of the tuberculosis bacillus in the urine is achieved through Ziehl-Neelsen’s acid-fast staining technique or through urine culture in Lowenstein-Jensen medium.68,69 The former is quick, with 96.7% specificity but only 42.1% to 52.1% sensitivity.68,69 Culture is the diagnostic gold standard for urogenital tuberculosis. Because bacilluria is sporadic and faint, 3 to 6 early-morning midstream samples are required. Sensitivity varies widely, from 10.7% to 90%, and the results can take 6 to 8 weeks to obtain.2,13,16,44

Some findings, such as leukocyturia, hematuria, acid urine, and negative culture, suggest urogenital tuberculosis and may be present in up to 93% of patients.11 Yet the suspicion of tuberculosis should not be based on these findings alone because alterations in the urine were described in only 22% to 27.6%.52,70 Urine culture yielding the usual pathogens may be obtained in 20% to 40% of urogenital tuberculosis cases and in up to 50% of female patients.1,14,16

Polymerase chain reaction for M tuberculosis identification in the urine has become the ideal diagnostic tool because it gives results in 24 to 48 hours and allows for diagnosis to be made even when there are few bacilli.13,69 Compared with culture it was 95.6% sensitive and 98.1% specific.69 Compared with bacteriologic, histologic, or clinicoradiologic diagnoses it was 94.3% sensitive and 85.7% specific.13

Intradermal injection of tuberculin leads to a late hypersensitivitylike local inflammatory reaction, with hard nodular formation after 48 to 72 hours. Patients are classified according to the induration diameter as nonreactors (< 5 mm), weak reactors (5–10 mm), or strong reactors (< 10 mm). The examination is not diagnostic: Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG)-vaccinated subjects are reactors, and when a nonvaccinated subject reacts this merely indicates previous contact with the bacillus. Yet when a previously weak reactor becomes a strong one, it indicates recent infection.1,2 The tuberculin test may contribute to the diagnosis of urogenital tuberculosis in countries without widespread BCG vaccination, a situation in which the test is positive in 85% to 95% of patients.11,42

Cystoscopy with bladder biopsy is a low-morbidity procedure that may be performed when there is clinical suspicion of tuberculosis and bacillus-negative urine, being more useful in the acute phase. The most frequent findings are local hyperemia, mucosal erosion and ulceration, tubercle formation, and irregularity of the ureteral meatuses. Bladder biopsy is 18.5% to 52% sensitive.13,70,71

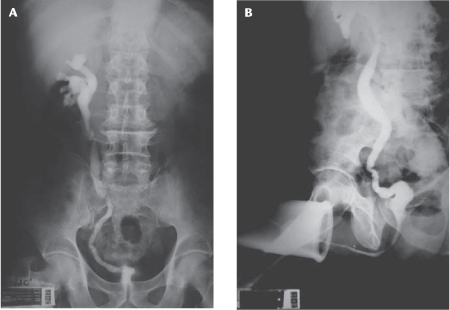

Imaging techniques are up to 91.4% sensitive for urogenital tuberculosis diagnosis, with intravenous urography and abdominal computerized tomography more frequently used.13 Findings suggesting urogenital tuberculosis are caliceal irregularities; infundibular stenosis; pseudotumor or renal scarring; nonfunctioning kidney; renal cavitation; urinary tract calcification (present in 7% to 19% of cases); collecting system thickening, stenosis, or dilatation; contracted bladder; and lesions in other organs beyond the urinary tract, such as lymph nodes, spleen, liver, and vertebrae.13,72,73 The simultaneous finding of kidney and bladder lesions is characteristic of tuberculosis, and the earliest findings are outline irregularity and caliceal dilatation due to infundibular stenosis.13 Multiple stenoses of the collecting system from the infundibulum to the ureterovesical junction are the findings most suggestive of urogenital tuberculosis, occurring in 60% to 84% of cases.65,72,74 In patients with a contracted bladder due to tuberculosis, the most frequent and characteristic radiologic finding is unilateral nonfunctioning kidney, contracted bladder, and vesicoureteral reflux into the functional contralateral kidney (Figure 3).75

Figure 3.

(A) Intravenous urography with left nonfunctioning kidney. (B) Voiding cystography showing contracted bladder and right vesicoureteral reflux.

Epididymal tuberculosis presents as a hypoechoic lesion involving the whole epididymis or just its head, with heterogeneous texture and concomitant testicular involvement in 38.9% of cases.76

Pharmacologic Treatment

A 3-drug regimen for the treatment of tuberculosis is justified: there is 80% relapse with a single drug, 25% with 2 drugs, and 10% with a triple regimen.11 After 2 weeks of treatment, no bacilli can be identified in the urine.1 Although the optimal treatment duration has not been defined, shorter-term treatments have been substituted for the traditional 18- and 24-month treatments initially recommended.6 Short-term (4- to 9-month) treatment is justified because of the good renal vascularization, high urinary concentration of the drugs used, low bacillary load in the urine, lower cost and toxicity, higher compliance, and similar efficacy compared with longer-duration regimens.5,9 Four- to 5-month treatments with nephrectomy of the excluded kidney have afforded relapse rates of less than 1%.62,70,77 Malnutrition and poor social conditions warrant treatment for longer than 9 months because relapse rates may be as high as 22% after a 6-month treatment and 19% after a 1-year treatment.16,58

Microbiologic relapse of urogenital tuberculosis may occur after initial urine sterilization, even after prolonged treatment and nephrectomy of the excluded kidneys.16,43,78 Relapses occurred in up to 6.3% of cases, after a mean of 5.3 years of treatment (range, 11 months to 27 years), with bacilli that were sensitive to the drugs initially used.58,79 Most investigators recommend a 10-year follow-up after pharmacologic treatment because of late relapse and the advantage of early treatment of initial lesions in the asymptomatic phase of relapse.16,43,78,79

Pharmacologic treatment may cure small renal foci and unblock the urinary collecting system.43,80 Nevertheless, it has been known since the 1970s that pharmacologic treatment may aggravate renal lesions just a few weeks after its start, with fibrosis induction leading to obstruction of the collecting system and vesical contraction, with worsening of frequency and development of renal functional exclusion.11,22,78,81

Surgical Treatment

More than half of patients (54.9%) with urogenital tuberculosis undergo surgery, a figure that ranges from 8% to 95% according to the timing of diagnosis.9,12,14–16,18,19,21,31,42–65 In series in which surgery was less frequent the patients were diagnosed when still asymptomatic, with fewer renal lesions.9,15 On the other hand, when the diagnosis is delayed the silent progression of the disease leads to organ destruction, with a greater frequency of surgical interventions.12

Surgery may be ablative, with removal of the tuberculosis-destroyed kidney or epididymis, or reconstructive for unblocking of the collecting system or augmentation of the contracted bladder.1,44,82 Recent decades have witnessed a decrease in the number of ablative surgeries and an increase in the number of reconstructive ones.62 The patient must be operated on after 4 to 6 weeks of pharmacologic treatment.1,43,70

Most investigators recommend nephrectomy without ureterectomy in cases of unilateral nonfunctioning kidney to avoid relapse, eliminate storage symptoms, treat hypertension, and avoid abscess formation.2,22,43,57,70,78 Because systemic arterial hypertension is more frequent in patients with urogenital tuberculosis with unilateral nonfunctioning kidney, nephrectomy can be curative of this condition in up to 64.7% of cases.43 Relapse is more likely when an excluded kidney is not removed, because pharmacologic treatment may not sterilize all tuberculosis foci; viable bacilli have been identified in the kidneys after 8 weeks and even 9 months of treatment.12,64,78

Conversely, after following 35 patients for up to 22 years, without any complication, some investigators recommend kidney preservation if there is no pain, infection, or bleeding.44,83

Laparoscopy has rarely been used because of high conversion rates, great perirenal adherence, and the possibility of caseous contamination of the peritoneal cavity. In 2 nonrandomized studies, however, laparoscopic nephrectomy for tuberculosis treatment did not lead to greater morbidity than the same approach to other benign conditions, with retroperitoneoscopic nephrectomy affording shorter hospital stay, fewer days of sick leave, and less pain as compared with open nephrectomy.72,84

Urinary collecting system obstruction is the main cause of functional exclusion, and the likelihood of renal function recovery in this situation is low.44 In selected cases of severe renal function reduction, however, urinary derivation may preserve these kidneys for posterior reconstruction.12 The positive predictive factors for functional recovery of obstructed kidneys are distal ureteral stenosis, cortical thickness greater than 5 mm, and a glomerular filtration rate above 15 mL/min as assessed by nephrostomy output or renal scintigraphy.12,78 On the other hand, intrarenal stenoses almost always lead to renal exclusion.22 In the rare instances in which an early diagnosis is made, percutaneous infundibulotomy is 80% successful, and the ileus may be interposed between the bladder and the dilated calices.74,81 Urinary derivation with a double-J ureteral catheter is only possible in 7.1% to 41% of tuberculosis cases.12,78

Ureteral stenosis is treated with dilatation or endoscopic incision, with a 50% to 90% success rate, or with reconstructive surgery.22,49,85

Contracted Bladder

Of patients with urogenital tuberculosis, 8.9% have fibrosis of the bladder wall, with capacity reduction and increased frequency of micturition.1,6 Although some investigators have reported good results with total cystectomy or cystoprostatectomy and orthotopic ileal neobladder to avoid stenosis of the enterovesical anastomosis and improve pain control, bladder augmentation is the treatment of choice for contracted bladder due to tuberculosis.21,86

The stomach, ileum, and colon are used to augment the bladder.87 In a review of 25 series of patients undergoing bladder augmentation with ileum, sigmoid, or ileocecal segments, no single segment proved superior; the choice depends on the surgeon’s preference.25 The bowel segment may be used in its original tubular shape or be detubularized to offer greater volume and less reservoir pressure.88 Because it is easily handled, the ileum is the most used segment for bladder augmentation at present.89 Because in tuberculosis cases there is a frequent need of ureteral reimplantation, sigmoid and ileocecal segments are also frequently used.75,89,90 An assessment of 25 patients who had undergone bladder augmentation because of tuberculosis revealed that the ileocecal segment may be used in its original tubular shape, whereas the sigmoid must be detubularized.75 In general, detubularization of the ileum or sigmoid is warranted, whereas the ileocecal segment, owing to its greater radius, may be used in its original tubular shape.

Bladder augmentation for tuberculosis is more successful than for other bladder problems such as neurogenic bladder, idiopathic detrusor hyperactivity, and inflammatory diseases.91,92 Good or satisfactory results with bladder augmentation are reached in almost all patients with tuberculosis.22,75,91,93–97 Table 3 shows the features of 270 patients with tuberculosis-related contracted bladder who underwent bladder augmentation.22,75,91,93–97 After bladder augmentation, tuberculosis patients have spontaneous void with the help of the Valsalva maneuver in most cases.75,89,96 The high postvoid residue after bladder augmentation occurs in patients with any obstructive factor, improving after surgical desobstruction.22,75,96 Some investigators recommend prostate resection in all subjects over 45 years of age contemplating bladder augmentation because of tuberculosis.93

Table 3.

Features of Urogenital Tuberculosis Patients Submitted to Bladder Augmentation

| Year | |||||||||

| Variable | Total | 196922 | 197097 | 197896 | 197993 | 198491 | 198794 | 200095 | 200675 |

| Total (N) | 270 | 12 | 33 | 30 | 51 | 15 | 40 | 88 | 25 |

| Men | 60 | 58.3 | 43.3 | 60.0 | 55.0 | 63.6 | 80 | ||

| Women | 40 | 41.7 | 56.7 | 40.0 | 45.0 | 36.4 | 20 | ||

| Age (years), | 33.9 | 29.7 | 32.7 | 40 | |||||

| median (range) | (12–70) | (15–42) | (17–70) | (14–62) | (12–60) | ||||

| Unilateral nonfunctioning kidney | 54.4 | 83.3 | 90.0 | 90.0 | 54.9 | 80.0 | 30.7 | 88 | |

| Renal failure | 7.8 | 8.3 | 6.1 | 6.7 | 0 | 15.0 | 4.5 | 20 | |

| Segment | |||||||||

| Ileum | 34.8 | 75.0 | 60.6 | 33.3 | 65.0 | ||||

| Sigmoid | 34.4 | 25.0 | 39.4 | 31.4 | 20.0 | 25.0 | 68 | ||

| Ileocecal | 30.7 | 100 | 68.6 | 46.7 | 10.0 | 32 | |||

| Results | |||||||||

| Good | 86.3 | 100 | 85.2 | 100 | 90.2 | 80.0 | 75.0 | 80 | |

| Satisfactory | 11.8 | 14.8 | 9.8 | 20.0 | |||||

| Bad | 1.9 | 20 | |||||||

Values are percentages unless otherwise noted.

Perspectives

Since the 1960s, early diagnosis of urogenital tuberculosis has been known to afford greater renal preservation.22 A systematic search for urogenital tuberculosis in patients with pulmonary disease yielded 10% culture positivity for the bacillus; 66.7% of these patients were asymptomatic, and 58% had normal results on urine examination and absence of lesions on intravenous urography.98 In 2 other series, in which cultures were obtained routinely and not as part of any symptom investigation, a greater frequency of asymptomatic patients without lesions on intravenous urography was found.44,79 Although bacilluria is invariably associated with renal lesion, detection of preclinical bacilluria allows for an earlier diagnosis in a moment when the initial lesions are amenable to cure and the severe, destructive course of urogenital tuberculosis may be averted.20 The importance of a systematic search to detect initial cases of urogenital tuberculosis, regardless of symptoms, must be emphasized. A better definition of groups at greater risk (subjects with previous pulmonary tuberculosis or immunosuppression) should be the subject of future studies.

Main Points.

Extrapulmonary sites account for 10% of tuberculosis cases. Urogenital tuberculosis is responsible for 30% to 40% of all extrapulmonary cases, second only to lymph-node involvement.

In most active cases of extrapulmonary disease, latent foci are reactivated after a decrease in immunity brought about by malnutrition, diabetes mellitus, steroid use, immunosuppressant use, and immunodeficiency. The latent period between pulmonary infection and clinical urogenital tuberculosis is, on average, 22 years.

Urogenital tuberculosis most frequently affects the kidneys. Ureteral and bladder tuberculosis is secondary to descending infection through the urinary collecting system. Urethral tuberculosis occurs in only 1.9% to 4.5% of all cases of urogenital tuberculosis and never as an isolated entity.

Genital tuberculosis occurs through hematogenic spread to the prostate and epididymides or through the urinary system to the prostate and canalicular spread to the seminal vesicles, deferent ducts, and epididymides.

Urogenital tuberculosis symptoms arise when there is bladder impairment. Storage symptoms, dysuria, and hematuria are the most common presentation. Diagnosis is rarely made before severe urogenital lesions develop, and 5.7% of patients develop endstage chronic renal failure.

Polymerase chain reaction for Mycobacterium tuberculosis identification in the urine has become the ideal diagnostic tool because it gives results in 24 to 48 hours and allows for diagnosis to be made even when there are few bacilli. Imaging techniques are up to 91.4% sensitive for urogenital tuberculosis diagnosis.

A 3-drug regimen for the treatment of tuberculosis is justified: there is 80% relapse with a single drug, 25% with 2 drugs, and 10% with a triple regimen.

More than half of patients (54.9%) with urogenital tuberculosis undergo surgery. Surgery may be ablative, with removal of the tuberculosis-destroyed kidney or epididymis, or reconstructive for unblocking of the collecting system or augmentation of the contracted bladder.

The importance of a systematic search to detect initial cases of urogenital tuberculosis, regardless of symptoms, must be emphasized, and a better definition of groups at greater risk should be the subject of future studies.

References

- 1.Gow JG. Genitourinary tuberculosis. In: Walsh PC, Retik AB, Vaughan ED, Wein AJ, editors. Campbell’s Urology. 7th ed. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders Company; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leite OHM. Tuberculosis. Problems Gen Surg. 2001;18:69–78. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cos LR, Cockett ATK. Genitourinary tuberculosis revisited. Urology. 1982;20:111–117. doi: 10.1016/0090-4295(82)90335-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Svahn A, Petrini B. Urogenital tuberculosis still a disease of current interest. Lakartidningen. 1992;89:1166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weinberg AC, Boyd SD. Short-course chemotherapy and role of surgery in adult and pediatric genitourinary tuberculosis. Urology. 1988;31:95–102. doi: 10.1016/0090-4295(88)90027-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carl P, Stark L. Indications for surgical management of genitourinary tuberculosis. World J Surg. 1997;21:505–510. doi: 10.1007/pl00012277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mayaud C, Cadranel J. Tuberculosis in AIDS: past or new problems? Thorax. 1999;54:567–571. doi: 10.1136/thx.54.7.567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Watters DA. Surgery for tuberculosis before and after human immunodeficiency virus infection: a tropical perspective. Br J Surg. 1997;84:8–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nzerue C, Drayton J, Oster R, Hewan-Lowe K. Genitourinary tuberculosis in patients with HIV infection: clinical features in an inner-city hospital population. Am J Med Sci. 2000;320:299–303. doi: 10.1097/00000441-200011000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Havlir DV, Barnes PF. Tuberculosis in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:367–373. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199902043400507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Psihramis KE, Donahoe PK. Primary genitourinary tuberculosis: rapid progression and tissue destruction during treatment. J Urol. 1986;135:1033–1036. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)45970-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ramanathan R, Kumar A, Kapoor R, Bhandari M. Relief of urinary tract obstruction in tuberculosis to improve renal function. Analysis of predictive factors. Br J Urol. 1998;81:199–205. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.1998.00500.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hemal AK, Gupta NP, Rajeev TP, et al. Polymerase chain reaction in clinically suspected genitourinary tuberculosis: comparison with intravenous urography, bladder biopsy, and urine acid fast bacilli culture. Urology. 2000;56:570–574. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(00)00668-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Christensen WI. Genitourinary tuberculosis. Review of 102 cases. Medicine (Baltimore) 1974;53:377–390. doi: 10.1097/00005792-197409000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alvarez S, McCabe WR. Extrapulmonary tuberculosis revisited: a review of experience at Boston City and other hospitals. Medicine (Baltimore) 1984;63:25–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gokalp A, Gultekin EY, Ozdamar S. Genitourinary tuberculosis: a review of 83 cases. Br J Clin Pract. 1990;44:599–600. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Medlar EM, Spain DM, Holliday RW. Postmortem compared with clinical diagnosis of genito-urinary tuberculosis in adult males. J Urol. 1949;61:1078–1088. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(17)69186-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Narayana AS. Overview of renal tuberculosis. Urology. 1982;19:231–237. doi: 10.1016/0090-4295(82)90490-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garcia-Rodríguez JÁ, García Sanchez JE, Muñoz Bellido JL. Genitourinary tuberculosis in Spain: review of 81 cases. Clin Infect Dis. 1994;18:557–561. doi: 10.1093/clinids/18.4.557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Medlar EM, Sasano KT. Experimental renal tuberculosis, with special reference to excretory bacilluria. Am Rev Tuberc. 1924;10:370–377. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mochalova TP, Starikov IY. Reconstructive surgery for treatment of urogenital tuberculosis: 30 years of observation. World J Surg. 1997;21:511–515. doi: 10.1007/pl00012278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kerr WK, Gale GL, Peterson KS. Reconstructive surgery for genitourinary tuberculosis. J Urol. 1969;101:254–266. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)62324-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Medlar EM. Cases of renal infection in pulmonary tuberculosis: evidence of healed tuberculous lesions. Am J Pathol. 1926;2:401–411. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barrie HJ, Kerr WK, Gale GL. The incidence and pathogenesis of tuberculous strictures of the renal pyelus. J Urol. 1967;98:584–589. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(17)62937-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Greenwell TJ, Venn SN, Mundy AR. Augmentation cystoplasty. BJU Int. 2001;88:511–525. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-4096.2001.001206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Winblad B, Duchek M. Spread of tuberculosis from obstructed and non-obstructed upper urinary tract. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand [A] 1975;83:229–236. doi: 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1975.tb01379.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Indudhara R, Vaidyanathan S, Radotra BD. Urethral tuberculosis. Urol Int. 1992;48:436–438. doi: 10.1159/000282372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Symes JM, Blandy JP. Tuberculosis of the male urethra. Br J Urol. 1973;45:432–436. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.1973.tb12184.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schubert GE, Haltaufderheide T, Golz R. Frequency of urogenital tuberculosis in an unselected autopsy series from 1928 to 1949 and 1976 to 1989. Eur Urol. 1992;21:216–223. doi: 10.1159/000474841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lubbe J, Ruef C, Spirig W, et al. Infertility as the first symptom of male genito-urinary tuberculosis. Urol Int. 1996;56:204–206. doi: 10.1159/000282842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kao SC, Fang JT, Tsai CJ, et al. Urinary tract tuberculosis: a 10-year experience. Changgeng YI Xue Za Zhi. 1996;19:1–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sporer A, Auerbach O. Tuberculosis of prostate. Urology. 1978;11:362–365. doi: 10.1016/0090-4295(78)90232-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kostakopoulos A, Economou G, Picramenos D, et al. Tuberculosis of the prostate. Int Urol Nephrol. 1998;30:153–157. doi: 10.1007/BF02550570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hemal AK, Aron M, Nair M, Wadhwa SN. Autoprostatectomy: an unusual manifestation in genitourinary tuberculosis. Br J Urol. 1998;82:140–141. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.1998.00710.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee YH, Huang WC, Huang JS, et al. Efficacy of chemotherapy for prostatic tuberculosis—a clinical and histologic follow-up study. Urology. 2001;57:872–877. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(01)00906-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Trauzzi SJ, Kay CJ, Kaufman DG, Lowe FC. Management of prostatic abscess in patients with human immunodeficiency syndrome. Urology. 1994;43:629–633. doi: 10.1016/0090-4295(94)90176-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gueye SM, Ba M, Sylla C, et al. Epididymal manifestations of urogenital tuberculosis. Prog Urol. 1998;8:240–243. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ross JC, Gow JG, St Hill CA. Tuberculous epididymitis. A review of 170 patients. Br J Urol. 1961;48:663–666. doi: 10.1002/bjs.18004821218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pryor JP, Hendry WF. Ejaculatory duct obstruction in subfertile males: analysis of 87 patients. Fertil Steril. 1991;65:725–730. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)54606-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vasanthi R, Ramesh V. Tuberculous infection of the male genitalia. Australas J Dermatol. 1991;32:81–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-0960.1991.tb00069.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ramesh V, Vasanthi R. Tuberculous cavernositis of the penis: case report. Genitourin Med. 1989;65:58–59. doi: 10.1136/sti.65.1.58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Simon HB, Weinstein AJ, Pasternak MS, et al. Genitourinary tuberculosis. Am J Med. 1977;63:410–420. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(77)90279-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Flechner SM, Gow JG. Role of nephrectomy in the treatment of non-functioning or very poorly functioning unilateral tuberculous kidney. J Urol. 1980;123:822–825. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)56149-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ferrie BG, Rundle JSH. Genito-urinary tuberculosis in Glasgow 1970 to 1979: a review of 230 patients. Scott Med J. 1985;30:30–34. doi: 10.1177/003693308503000107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Caro Muñoz M, Corvalán JR, Tenório JP, Vergara JF. Diagnosis of urogenital tuberculosis: a retrospective review (1974–1986) Bol Hosp San Juan de DÍos. 1988;35:223–226. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Venegas MP, Corti OD, Foneron BA. Genitourinary TBC: experience of Hospital de Valdiva 1979–1984 years. Rev Chil Urol. 1990;53:131–134. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Núñez Vásquez N, Susaeta SR, Vogel M, Olate C. Genitourinary tuberculosis study: urologic service, Hospital San Juan de Dios 1975–1989. Rev Chil Urol. 1990;53:135–137. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Allen FJ, de Kock ML. Genito-urinary tuberculosis—experience with 52 urology inpatients. S Afr Med J. 1993;83:903–907. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bennani S, Hafiani M, Debbagh A, et al. Urogenital tuberculosis. Diagnostic aspects. J Urol (Paris) 1995;101:187–190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hinostroza Fuschlocher JÁ, Gorena Palominos M, Pastor Arroyo P, et al. Genitourinary tuberculosis at Araucanía: experience at Hospital Regional de Temuco. Rev Chil Urol. 1998;63:113–117. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mnif A, Loussaief H, Ben Hassine L, et al. Aspects of evolving urogenital tuberculosis. 60 cases. Ann Urol (Paris) 1998;32:283–289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lopez de Mesa B, Cruz A, Gomes P. Review of patients with genitourinary tuberculosis in San Juan de Dios Hospital. Urol Colomb. 1998;7:43–52. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bencheckroun A, Lachkar A, Soumana A, et al. Urogenital tuberculosis. 80 cases. Ann Urol (Paris) 1998;32:89–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chtourou M, Kbaier I, Attyaoui F, et al. Management of genito-urinary tuberculosis. A report of 225 cases. J Urol. 1999;161(4 suppl):9. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Buchholz NP, Salahuddin S, Haque R. Genitourinary tuberculosis: a profile of 55 in-patients. J Pak Med Assoc. 2000;50:265–269. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hemal AK, Gupta NP, Kumar R. Comparison of retroperitoneoscopic nephrectomy with open surgery for tuberculous nonfunctioning kidneys. J Urol. 2000;164:32–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.El Khader K, Lrhorfi MH, El Fassi J, et al. Urogenital tuberculosis. Experience in 10 years. Prog Urol. 2001;11:62–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gokce G, Kilicaerslan H, Ayan S, et al. Genitourinary tuberculosis: review of 174 cases. Scan J Infect Dis. 2002;34:338–340. doi: 10.1080/00365540110080331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Barrios F, Martinez-Peschard L, Rosas A. Surgical management of tuberculosis. BJU Int. 2002;90(suppl 2):26. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ishibashi Y, Takeda T, Nishimura R, Ohshima H. A clinical observation of genitourinary tract tuberculosis during the last decade. Hinyokika Kiyo. 1985;31:107–112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gow JG. Genitourinary tuberculosis: a 7-year review. Br J Urol. 1979;51:239–244. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.1979.tb04700.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gow JG, Barbosa S. Genitourinary tuberculosis. A study of 1117 cases over a period of 34 years. Br J Urol. 1984;56:449–455. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Fuse H, Imazu A, Shimazaki J. A clinical observation on urogenital tuberculosis. Hinyokika Kiyo. 1984;30:299–304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Fischer M, Flamm J. The value of surgical therapy in the treatment of urogenital tuberculosis. Urologe A. 1990;29:261–264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zwergel U, Wullich B, Rohde V, Zwergel T. Surgical management of urinary tuberculosis: a review of 341 patients. J Urol. 1999;161(4 suppl):9. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Marques LP, Rioja LS, Oliveira CA, Santos OD. AIDS-associated renal tuberculosis. Nephron. 1996;74:701–704. doi: 10.1159/000189477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chattopadhyay A, Bhatnagar V, Agarwala S, Mitra DK. Genitourinary tuberculosis in pediatric surgical practice. J Ped Surg. 1997;32:1283–1286. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(97)90302-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mortier E, Pouchot J, Girard L, et al. Assessment of urine analysis for the diagnosis of tuberculosis. Br Med J. 1996;312:27–28. doi: 10.1136/bmj.312.7022.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Moussa OM, Eraky I, El-Far MA, et al. Rapid diagnosis of genitourinary tuberculosis by polymerase chain reaction and non-radioactive DNA hybridization. J Urol. 2000;164:584–588. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wong SH, Lau WY, Poon GP, et al. The treatment of urinary tuberculosis. J Urol. 1984;131:297–301. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)50354-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Shapiro AL, Viter VI. Cystoscopy and endovesical biopsy in renal tuberculosis. Urol Nefrol (Mosk) 1989;1:12–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wang LJ, Wu CF, Wong YC, et al. Imaging findings of urinary tuberculosis on excretory urography and computerized tomography. J Urol. 2003;169:524–528. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000040243.55265.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lu P, Li C, Zhou X. Significance of the CT scan in renal tuberculosis. Zhonghua Jie He He Hu Xi Za Zhi. 2001;24:407–409. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hwang TK, Park YH. Endoscopic infundibulotomy in tuberculous renal infundibular stricture. J Urol. 1994;151:852–854. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)35104-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Figueiredo AA, Lucon AM, Srougi M. Bladder augmentation for the treatment of chronic tuberculous cystitis. Clinical and urodynamic evaluation of 25 patients after long term followup. Neurourol Urodyn. 2006;25:433–440. doi: 10.1002/nau.20264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Chung JJ, Kim MJ, Lee T, et al. Sonographic findings in tuberculous epididymitis and epididynorchitis. J Clin Ultrasound. 1997;25:390–394. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0096(199709)25:7<390::aid-jcu7>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Skutil V, Varsa J, Obsitnik M. Six-month chemotherapy for urogenital tuberculosis. Eur Urol. 1985;11:170–176. doi: 10.1159/000472484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wong SH, Lau WY. The surgical management of non-functioning tuberculous kidneys. J Urol. 1980;124:187–191. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)55367-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Butler MR, O’Flynn D. Reactivation of genitourinary tuberculosis. Eur Urol. 1975;1:14–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Carl P, Stark L. Ileal bladder augmentation combined with ileal ureter replacement in advanced urogenital tuberculosis. J Urol. 1994;151:1345–1347. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)35248-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Wong SH, Chan SL. Pan-calicealileoneocystostomy—a new operation for intrapelvic tuberculotic strictures of the renal pelvis. J Urol. 1981;126:734–736. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)54723-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.O’Flynn D. Surgical treatment of genito-urinary tuberculosis: a report on 762 cases. Br J Urol. 1970;42:667–671. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.1970.tb06789.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Bloom S, Wechsler H, Lattimer JK. Results of long-term study of nonfunctioning tuberculous kidneys. J Urol. 1970;104:654–657. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)61803-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Lee KS, Kim HH, Byun SS, et al. Laparoscopic nephrectomy for tuberculous nonfunctioning kidney: comparison with laparoscopic simple nephrectomy for other diseases. Urology. 2002;60:411–414. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(02)01759-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Debre B. Urogenital tuberculosis: current status and future perspectives. Sem Hop. 1982;58:298–305. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Hemal AK, Aron M. Orthotopic neobladder in management of tubercular thimble bladders: initial experience and long-term results. Urology. 1999;53:298–301. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(98)00504-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Gouch DCS. Enterocystoplasty. BJU Int. 2001;88:739–743. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-4096.2001.gough.2464.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Lytton B, Green D. Urodynamic studies in patients undergoing bladder replacement surgery. J Urol. 1989;141:1394–1397. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)41320-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Dounis A, Abel BJ, Gow JG. Cecocystoplasty for bladder augmentation. J Urol. 1980;123:164–167. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)55834-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Nahas WC, Lizuka FA, Mazzucchi E, et al. Adenocarcinoma of an augmented bladder 25 years after ileocecocystoplasty and 6 years after renal transplantation. J Urol. 1999;162:490–491. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Lunghi F, Nicita G, Selli C, Rizzo M. Clinical aspects of augmentation enterocystoplasties. Eur Urol. 1984;10:159–163. doi: 10.1159/000463779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Whitmore WF, Gittes RF. Reconstruction of the urinary tract by cecal and ileocecal cystoplasty: review of a 15-year experience. J Urol. 1983;129:494–498. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)52198-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Dounis A, Gow JG. Bladder augmentation—a long term review. Br J Urol. 1979;51:264–268. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.1979.tb04706.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Benchekroun A, Hachimi M, Marzouk M, et al. Enterocystoplasty in 40 cases of tuberculous cystitis. Acta Urol Belg. 1987;55:583–590. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Aron M, Gupta NP, Hemal AK, et al. Surgical management of advanced bladder tuberculosis. Aust N Z J Surg. 2000;70:A20. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Abel BJ, Gow JG. Results of caecocystoplasty for tuberculous bladder contracture. Br J Urol. 1978;50:511–516. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.1978.tb06202.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Wesolowski S. Late results of cystoplasty in chronic tuberculous cystitis. Br J Urol. 1970;42:697–703. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.1970.tb06794.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Bentz RR, Dimcheff DG, Nemiroff J, et al. The incidence of urine cultures positive for Mycobacterium tuberculosis in a general tuberculosis patient population. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1975;3:647–650. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1975.111.5.647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]