Abstract

The primary auditory cortex is now known to be involved in learning and memory, as well as auditory perception. For example, spectral tuning often shifts toward or to the frequency of the conditioned stimulus during associative learning. As previous research has focused on tonal frequency, less is known about how learning might alter temporal parameters of response in the auditory cortex. This study addressed the effects of learning on the fidelity of temporal processing. Adult male rats were trained to avoid shock that was signaled by an 8.0 kHz tone. A novel control group received non-contingent tone and shock with shock probability decreasing over days to match the reduced number of shocks received by the avoidance group as they mastered the task. An untrained (naïve) group served as a baseline. Following training, neuronal responses to white noise and a broad spectrum of tones were determined across the primary auditory cortex in a terminal experiment with subjects under general anesthesia. Avoidance conditioning significantly improved the precision of spike timing: the coefficient of variation of 1st spike latency was significantly reduced in avoidance animals compared to controls and naïves, both for tones and for noise. Additionally, avoidance learning was accompanied by a reduction of the latency of peak response, by 2.0–2.5 ms relative to naïves and ~1.0 ms relative to controls. The shock-matched controls also exhibited significantly shorter peak latency of response than naïves, demonstrating the importance of this non-avoidance control. Plasticity of temporal processing showed no evidence of frequency-specificity and developed independently of the non-temporal parameters magnitude of response, frequency tuning and neural threshold, none of which were facilitated. The facilitation of temporal processing suggests that avoidance learning may increase synaptic strength either within the auditory cortex, in the subcortical auditory system, or both.

Keywords: Instrumental conditioning, Associative learning, Plasticity, Synaptic strength

A key challenge for neurobiology is the identification of changes in neural activity that constitute the bases of learning and memory. Traditionally, most attention has been directed to structures such as the hippocampus, amygdala, striatum, cerebellum and non-sensory regions of the cerebral cortex. Although research starting in the 1950s revealed that sensory systems, particularly primary auditory cortex, develop associative plasticity during classical and instrumental conditioning (reviewed in Weinberger & Diamond, 1987), interest in sensory cortical plasticity and learning remained minimal until sensory neurophysiology techniques were combined with standard learning tasks in the mid-1980s. Such studies revealed that learning was accompanied by highly specific modification of conditioned stimulus (CS) representation (Gonzalez-Lima & Scheich, 1984, 1986) and CS-directed shifts of frequency receptive fields (Diamond & Weinberger, 1986; Weinberger, Diamond, & McKenna, 1984). Although not studied as extensively, learning-related plasticity develops in primary somatosensory and visual, as well as auditory, cortices (reviewed in, e.g., Diamond, Petersen, & Harris, 1999; Gilbert, Sigman, & Crist, 2001; Rauschecker, 1999; Scheich, Stark, Zuschratter, Ohl, & Simonis, 1997; Weinberger, 2004).

Systematic studies of fear conditioning showed that CS-specific tuning shifts have the major characteristics of associative memory, i.e., they are associative, highly specific, rapidly induced, discriminative, consolidate (become stronger over hours and days without further training) and show long-term retention (measured to 8 weeks) (reviewed in Weinberger, 1995, 1998). Such tuning shifts develop with rewarding, as well as aversive reinforcers (Kisley & Gerstein, 2001) and during instrumental avoidance, as well as classical, conditioning (Bakin, South, & Weinberger, 1996). Frequency-specific tuning shifts might be expected to produce an increase in the area of representation of CS frequencies as more cells become “recruited” to such stimuli and this effect has been found both in associative learning (Rutkowski & Weinberger, 2005) and perceptual learning for increased frequency acuity (Recanzone, Schreiner, & Merzenich, 1993; but see Brown, Irvine, & Park, 2004). Moreover, the basic findings in animal subjects have been replicated and extended to humans (e.g., Morris, Friston, & Dolan, 1998). Learning and memory may also be critical in the development of sensory cortical plasticity following peripheral denervation or related injury (Merzenich & Sameshima, 1993), and have direct implications for the alleviation or remediation of neuropathological conditions resulting from sensory deprivation, and recovery from brain injury (e.g., Palmer, Nelson, & Lindley, 1998).

Although it has now been firmly established that the primary auditory cortex is involved in learning and memory, a prime issue concerns the dimensions of sensory processing that are modified by associative learning. The vast majority of research has concerned acoustic frequency. More recently, the scope of inquiry has expanded to other parameters and, similar to acoustic frequency, learning enhances responses to acoustic features that become behaviorally important signals, e.g., the stimulus level (loudness) (Polley, Heiser, Blake, Schreiner, & Merzenich, 2004; Polley, Steinberg, & Merzenich, 2006), the repetition rate of simple sounds (Bao, Chang, Woods, & Merzenich, 2004) and the modulation rate of frequency-modulated (FM) sounds (Beitel, Schreiner, Cheung, Wang, & Merzenich, 2003).

In addition to the magnitude of neural responses to acoustic features, learning might also modify their temporal processing, including the latency and variability of neuronal response (Edeline, 2005). Plasticity of response latency in auditory learning has not been heavily studied. An experiment of extended frequency discrimination training in the owl monkey led to good perceptual learning accompanied by increases in the latency of auditory cortical response on the order of ~1.0 ms (Recanzone et al., 1993). In contrast, an investigation of two-tone discriminated avoidance learning in the rabbit indicates that after learning peak responses to a CS+ are of shorter latency than responses to a CS− in the medial geniculate body (Gabriel, Saltwick, & Miller, 1975).

The goal of the present experiment was to investigate learning-related changes in response latency and precision of spike-timing in the primary auditory cortex during avoidance conditioning. We studied avoidance learning because, unlike some forms of classical conditioning, e.g., simple fear conditioning, it requires intact auditory cortex (e.g., Delay & Rudolph, 1994; Duvel, Smith, Talk, & Gabriel, 2001; Scharlock & Miller, 1964).

METHODS

Subjects

The subjects were 18 adult male Sprague–Dawley rats (300–400 grams, Charles River, Hollister, CA) housed individually with ad libitum food and water, on a 12/12h light–dark cycle (lights on at 7:00 AM). Following several days of adaptation to the vivarium and handling they were assigned to one of three groups: avoidance (AV, n = 5), control (CN, n = 5) and naïve (NV, n = 8). Groups AV and CN underwent training with tone and shock in a shuttle box, followed by a terminal recording session while under general anesthesia. Group NV underwent terminal recording from A1 without any training. All procedures were performed in accordance with the University of California at Irvine Animal Research Committee and the NIH Animal Welfare guidelines.

Apparatus and Training

The training apparatus (Coulbourn Instruments, Allentown, PA) consisted of a rat shuttle box (20″W × 10″D × 12″H; #H10-11R-SC) equipped with a speaker (#H12-01R) and a grid floor separately wired for each half of the box. The speaker was centrally located in the box’s ceiling and could be driven by a sine-wave generator (#H12-07) and programmed to emit a tone (8.0 kHz, 70 dB at animal’s head level throughout the box). The grid floor could deliver an 8-pole scrambled shock delivered from a constant current shocker (60 Hz, 1.5 mA; #H13-15). The shuttle box was contained within an acoustic chamber (Industrial Acoustics, Bronx, NY) and dimly illuminated from above. Stimuli and behavioral responses were controlled and recorded by a PC, respectively, running under Coulbourn Graphic State software.

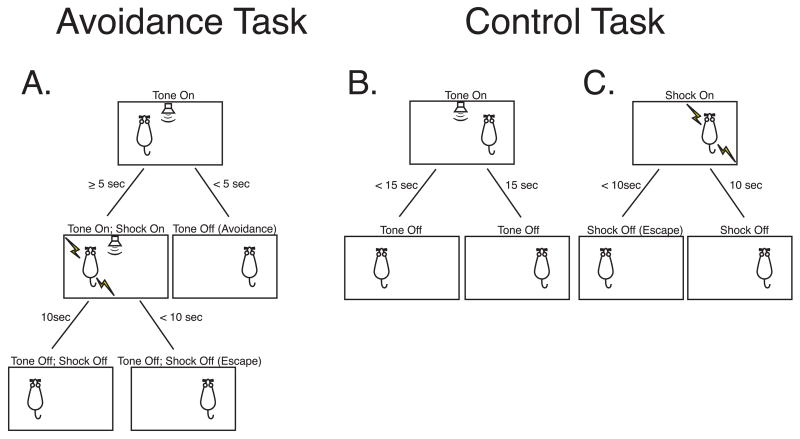

Both groups AV and CN received escape training (50 trials shock only) on Day 1, and 10 trials of escape training at the start of Day 2, after which avoidance or control training began immediately. During escape training, shock was presented at unpredictable times (mean intertrial interval = 45 s, range = 30–90 s). If subjects failed to cross to the other side of the shuttle box within 10 s, shock was terminated. Group AV was trained on the avoidance task shown in Figure 1A. The tone was presented for a maximum of 15 s. If the rat crossed to the opposite side of the shuttle box within 5 s of tone onset, the tone was terminated, no shock was given and the trial was completed. Failure to cross within 5 s resulted in footshock, which could be immediately escaped (i.e., terminated) by crossing to the other side. In the absence of escape, footshock lasted for a maximum of 10 s, at which point the shock and tone were simultaneously terminated. Inter-trial intervals averaged 45 s (range = 30–90 s). A session consisted of 50 tone presentations. AV subjects underwent terminal auditory cortex recording 24 hours after the completion of training. They were trained until they reached a stable level of behavior across four consecutive sessions, defined as a coefficient of variation (CV) ≤ 0.10 (i.e., 10% of the four-day mean of percent avoidances). However, due to experimental error, one subject underwent auditory cortex recording after two days, at which point it had reached 65% avoidance (i.e., avoided shock on 65% of trials). The number of days of training and number of animals were: 2 (n = 1), 5 (n = 1), 6 (n = 1), 7 (n = 2).

Figure 1.

(A) Auditory Avoidance Task. Adult male rats avoided shock if they moved to the opposite side of a shuttlebox within 5 s after onset of a tone (8 kHz, 70 dB), or escaped shock (maximum duration = 10 s) if their response latencies were > 5 s. Responses terminated the tone on successful avoidance trials and terminated both tone and shock on escape trials. Daily training sessions consisted of 50 tone presentations. (B) Control Task. Control rats received the same density of tone and shock, which were presented pseudo-randomly (minimum inter-stimulus intervals = 20 s). Across sessions, the number of pre-programmed foot shocks administered to control rats was gradually decreased to match the reduction in foot shocks experienced by avoidance rats as their performance improved. Responses terminated the tone and provided escape from shock.

Group CN served as a control for exposure to tone and shock in the absence of avoidance learning. This control design consisted of the same unpredictable schedule of tones and shocks received by group AV, with the constraint that neither stimulus occurred within twenty seconds of the other, to avoid accidental (i.e., partial) tone–shock pairing. Thus, CN subjects could escape, but not avoid, shock. Additionally, it was appropriate to match the overall probability of shock across days of training because as group AV learned to avoid, its probability of shock decreased. Therefore, group CN was trained with decreasing probability of shock over days to approximate the shock density that had been experienced by Group AV (Figure 1B,C). As with AV, CN subjects received 50 tones per session. CN animals were trained for four sessions (n = 4), but one subject received a fifth session because of a one-day delay in auditory cortex recording due to an equipment problem. These procedures permitted inhibitory learning, i.e., that tone signaled a period free of shock, but actual post-training tests for such learning were not conducted in this particular study. This apparently novel avoidance control group was thought to be of major importance for the interpretation of results from the main avoidance group. Thus, even in the absence of detailed analysis of possible inhibitory learning, this group could potentially reveal that neuronal plasticity in the avoidance group was caused by avoidance training per se, rather than by the presentation of tone and shock.

Terminal Surgery and Electrophysiology

Surgical and electrophysiological methods were essentially the same as reported previously (Rutkowski, Miasnikov, & Weinberger, 2003). All animals were anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (50 mg/kg, i.p.) with supplemental doses administered (15 mg/kg, i.p.) to maintain suppression of the forepaw withdrawal reflex. Bronchial secretions were minimized by treatment with atropine sulphate (0.22 mg/kg, i.m.) and core body temperature was maintained at 37° C via a heating blanket and monitored with a rectal probe. Animals were placed in a stereotaxic frame inside a sound attenuated room (Industrial Acoustics Company) and the skull was fixed to a support via a pedestal made from dental cement, which left the ear canals unobstructed. A craniotomy was performed over the right auditory cortex and the cisternae magnum was drained of CSF to minimize cerebral edema. After reflection of the dura, a thin layer of warmed silicon oil was applied to the cortical surface to prevent desiccation. Multi-unit extracellular recordings were made using a fixed array of four microelectrodes spaced 305 μm apart (1–3 MΩ impedance; FHC, Bowdoin, ME) and lowered to a depth of 400–700 μm from the cortical surface. Using a digital camera (Nikon Coolpix 4500) attached to a zoom stereomicroscope (Nikon SMZ660), an image was taken of the microelectrode array tips at the site of each electrode penetration. This allowed us to register the precise cortical location of each penetration and to later reconstruct tonotopic maps. Multiple penetrations were made along the frequency axis of A1, in order to determine if it had been altered by training, e.g., increase in the number of sites tuned to the CS frequency. However, no attempt was made to obtain a complete map of A1 and therefore the issue of area of representation for various frequency bands was not addressed in this study. At the completion of recording, animals were euthanized with an overdose of sodium pentobarbital.

Acoustic Stimulus Presentation

Acoustic stimuli were generated using Tucker Davis Technologies (TDT, Alachua, FL) System 3 hardware and software and were presented monaurally via a calibrated speaker (Aiwa) placed against the left (contralateral) ear canal. Unit cluster responses were tested under two stimulus protocols that were used to obtain responses to tone and to noise from the same recording sites. The first protocol consisted of 28 pure-tone frequencies (0.5–53.8 kHz, 0.25 octave spacing), varying in 5 dB steps (~ −10 to 90 dB SPL) with each frequency-level combination presented randomly. The second protocol consisted of broadband noise (bandwidth = 1 Hz–50 kHz) that varied randomly in 5 dB steps, using the same stimulus levels as employed for the tone protocol. Both noise and pure tone bursts were 100 ms in duration and cosine gated with a rise/fall time (10–90%) of 8 ms, presented at a repetition rate of 1.4 Hz.

Recording and Neurophysiological Data Analysis

Multiunit action potentials were extracted from on-line voltage traces that were amplified (×10,000) and band-pass filtered (300 Hz–3000 Hz) using TDT System 3 hardware and software. The voltage waveforms for all “candidate” spikes were required to exceed both a positive and negative voltage threshold set by the experimenter. A conservative threshold criterion was used to achieve a good signal-to-noise ratio (~3:1) for accepted spikes and to avoid the collection of any “false-positive” data. The times of action potentials were marked as events with 40 μs precision (25 kHz sampling) and stored on disk for off-line analysis.

Stimulus-evoked responses were determined by comparing the average spike rate measured during the first 6 ms following the onset of the noise burst (hereafter referred to as the “background interval”) to the spike rate measured during the 7–40 ms interval following burst onset (hereafter referred to as the “response interval”). A response was defined as a spike rate during the response interval that was ≥ 3.0 s.e. above the background rate of discharge. Threshold was defined as the lowest stimulus level that exhibited a response, provided that responses were elicited at 3 consecutive stimulus levels (corresponding to a 15 dB range). The CF for a cluster was defined as the tonal frequency with the lowest overall threshold (across all 28 rate-level plots). On the few occasions that the lowest threshold occurred at more than one tone, we defined the CF as the geometric mean of those tones.

All neurophysiological data reported in this paper were obtained from neural clusters determined to reside within area A1 on the basis that they (1) showed short-latency (15–30 ms across high to low stimulus levels), evoked responses to noise bursts and tones, (2) had a lower tone (CF) threshold than noise threshold and (3) were located along a gradient of low to high frequency CFs from posterior to anterior positions. Recordings were considered to be in the “mirror-image” anterior field when the frequency gradient reversed (Doron, LeDoux, & Semple, 2002; Horikawa, Ito, Hosokawa, Homma, & Murata, 1988; Rutkowski et al., 2003; Sally & Kelly, 1988) and were not included in this report. A total of 393 clusters satisfied these criteria: 136 from group AV, 119 from group CN, and 138 from group NV.

RESULTS

Avoidance Conditioning

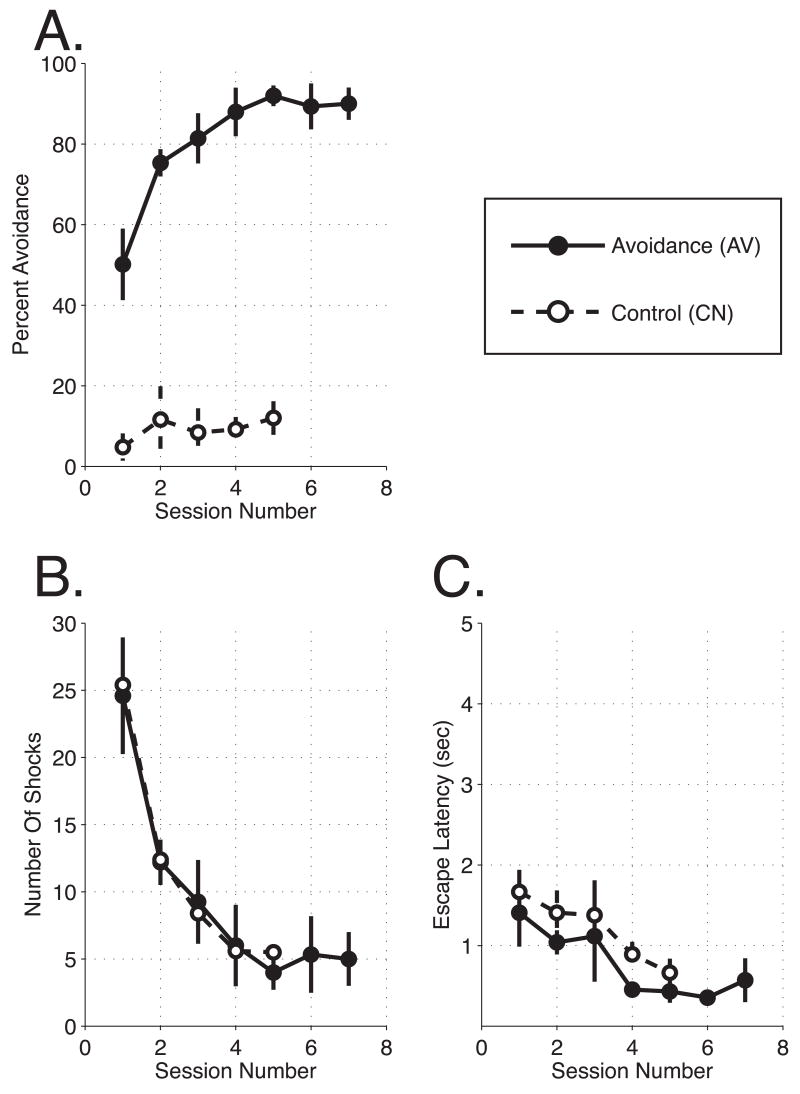

Both groups AV and CN exhibited rapid escape behavior on Day 1 and during the first 10 shock-only trials on Day 2. During subsequent avoidance training, the AV group rapidly learned to avoid footshock. At the end of the first day of training, they averaged ~50% avoidances and achieved ~90% on day 5 (Figure 2A). Group CN rats, which experienced random delivery of tones and shocks, did not develop the same responses to the tone. Their crossing of the shuttlebox during the tone increased from ~5% on Day 1 to ~10% of the trials on subsequent days (Figure 2A). This may reflect increased general activity due to the presence of shocks. The differences in behavior cannot be attributed to differences in the probability of shock as the number of shocks per session for group CN was matched to the AV animals (Figure 2B). Neither was the lack of responses to the tone in group CN due to any motor impairment as their shock escape latencies were rapid (Figure 2C). Thus, we conclude that the behavior of the AV group reflected associative instrumental learning.

Figure 2.

Behavioral Measurements. (A) Group Performance. Avoidance rats demonstrated rapid improvement across experimental sessions, attaining ~90% avoidance responses. Due to the nature of the task, control rats were unable to avoid shock. Control rats showed no such learning function. (B) Shock Density. The average number of shocks received by groups across sessions. The programmed number of shocks presented to control rats was not significantly different from the avoidance group. (C) Escape Latency. Both groups of rats showed good escape behavior. However, across sessions the escape latencies of the avoidance group were consistently shorter than control group latencies. This difference may reflect escape responses when avoidance rats were in the act of crossing the shuttle box just before the shock was presented.

Effects of Training on A1 Responses to Tones

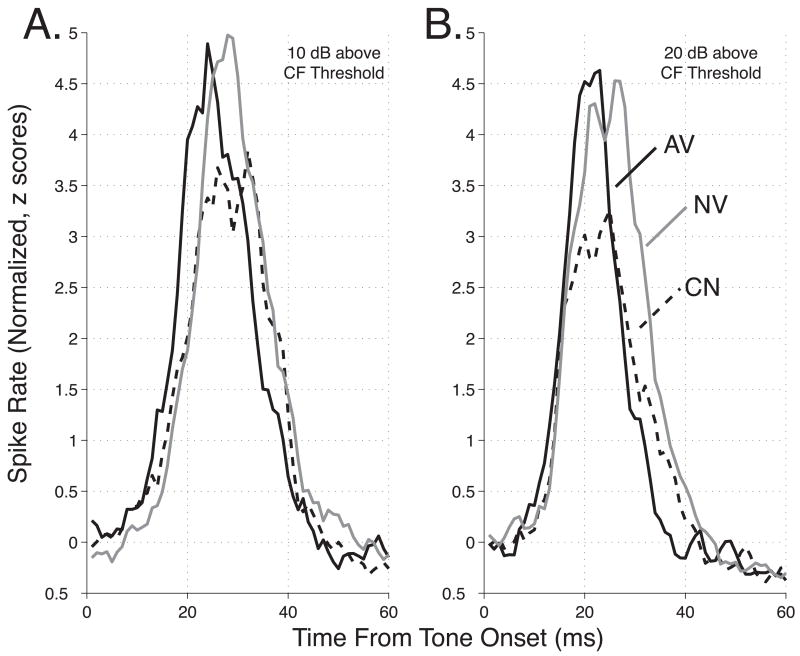

Population post-stimulus time histograms (PSTHs) provide an overview of the response profile of each group. Population PSTHs pooled across all CFs at 10 dB and 20 dB above each cluster’s threshold are shown in Figures 3A and 3B, respectively. These plots indicate that neurons from avoidance animals tended to reach their peak response earlier than neurons from both control and naïve subjects. Moreover, whereas the magnitude of the peak response was similar for group AV and NV, it was noticeably smaller in group CN that had received random tone and shock. One possible explanation for this difference in response magnitude is that neurons from control animals simply exhibited greater variability in the latency of their peak responses. This would cause the peak magnitude of the corresponding population response to appear smaller, on average, than the peak magnitude for individual clusters. To resolve this issue, we examined the responses of individual clusters, focusing primarily on three parameters: the peak latency, the magnitude of the peak response, and the 1st spike latency.

Figure 3.

Neural Population Responses to Pure Tones. The graph shows the average neural responses (bin-width = 3 ms) to tones determined at 10 dB (A), and 20 dB (B) above CF threshold. Responses for each cluster were converted to z-scores using the mean and standard deviation of spike rate during the first 60 ms after tone onset. The plots demonstrate a reduced peak latency in the avoidance group (AV = solid), relative to both naïve (NV = gray) and control (CN = dashed) responses, and a reduced peak magnitude in the control group. These between-group differences were confirmed on the basis of individual cluster analyses, and across a broad range of stimulus levels (see text).

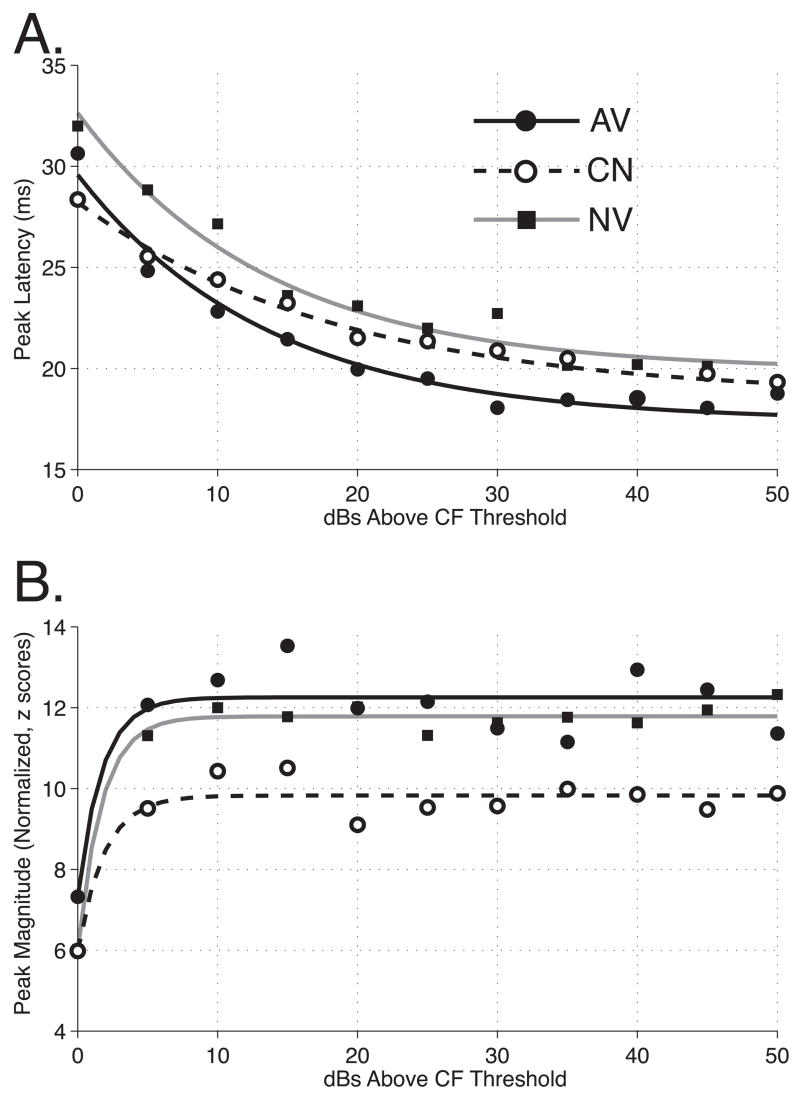

Peak Latency

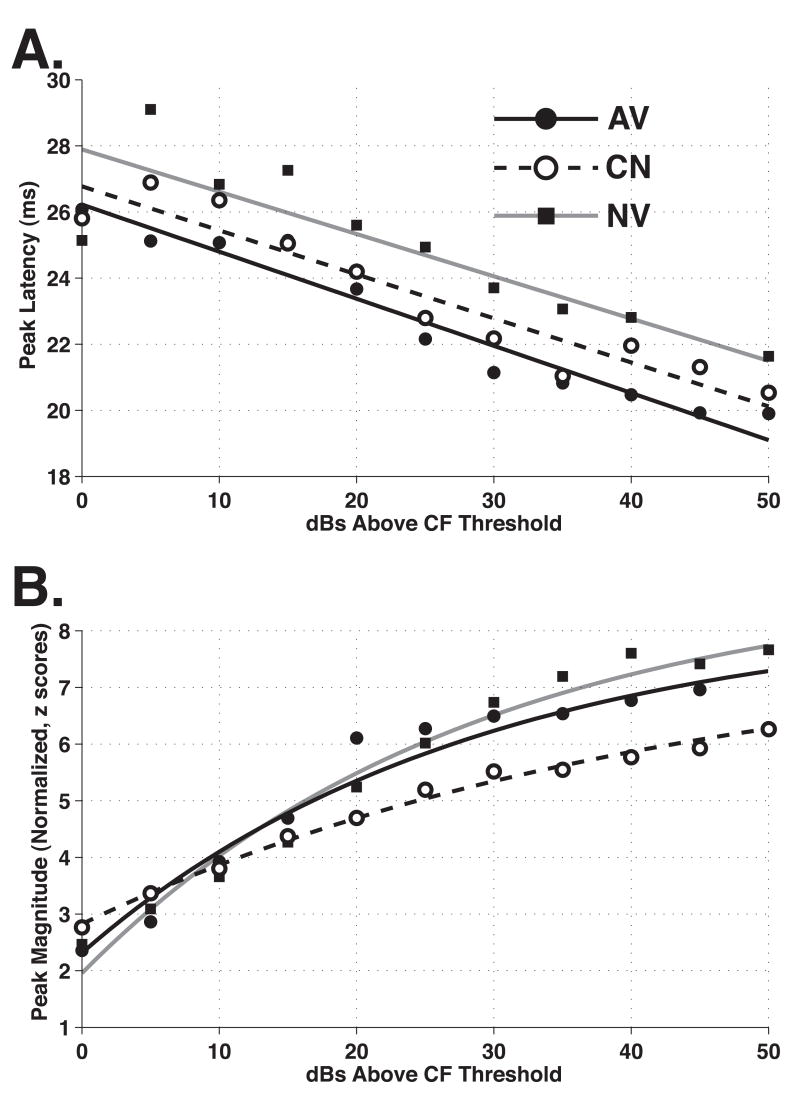

Peak latencies appear to be influenced by behavioral training. The average peak latencies are shown in Figure 4A. All three groups exhibited a clear reduction in latency as a function of stimulus level (relative to CF threshold), as is typical of neurons in the auditory system. However, more importantly, the AV group exhibited the shortest average latencies, ~1.1 ms shorter than the CN group and ~2.6 ms shorter than the NV group, across stimulus level. Random pairing of tone and shock also led to a reduction in latencies, reducing them by ~1.4 ms relative to naïve data. This finding indicates that the use of a shock-matched control group is helpful in estimating the effects of avoidance learning per se.

Figure 4.

The Effects of Behavioral Training on Peak Responses to Pure Tones. (A) Peak Latencies vs. Stimulus Level. Peak latencies for each cluster were determined from average spike rates (bin-width = 3 ms) measured for the first 60 ms after tone onset. Neural clusters recorded from avoidance rats (AV = solid) showed significantly reduced peak latencies relative to both naïve (NV = gray) and control (CN = dashed) groups (p < 10−4 for both comparisons). Non-contingent presentation of tone and shock had a smaller effect on peak latencies; however compared to group NV, the reduction was still statistically significant (p < 10−6). (B) Peak Magnitudes vs. Stimulus Level. Avoidance training had no effect on the magnitude of the peak response. Peak magnitudes were obtained from responses that were first converted to z-scores using the mean and standard deviation of spike rates during the first 60 ms after tone onset. Neural clusters recorded from CN rats showed markedly reduced peak magnitudes relative to groups AV and NV (p < 10−7 for both comparisons).

We performed nonlinear least-squares regression in which we modeled the peak latencies as an exponential function of stimulus level (indicated by the variable LEV):

Peak Latency = [L + (l · Group)] + [U + (u · Group) − L + (l · Group)] · [exp(−LEV)]β

When “Group = 1,” separate equations are fit to the two sets of data being compared. The parameters L and U refer to the lower and upper asymptotes for one fitted curve. The second curve’s lower and upper asymptotes are equal to L + l, and U + u, respectively. The slope parameter, β, is common to both curves. To test for statistically significant differences, we compared these fits to a “reduced” model in which the two data sets are treated as one (i.e., Group = 0, thus l = u = 0) and applied the principle of “extra sum of squares” (Draper & Smith, 1998). This analysis yielded significant differences between all three groups: [AV vs. NV: F(2, 2635) = 31.4; p = 3.2 × 10−14; CN vs. NV: F(2, 2489) = 13.4; p = 1.6 × 10−6; AV vs. CN: F(2, 2431) = 9.3; p = 9.3 × 10−5]. Thus, latencies to peak response were significantly different among groups: AV < CN < NV (Table 1).

Table 1.

Responses to Tone

| Group | Peak Magnitude (z-scores) | Peak Latency (ms) | 1st Spike Latency (ms) | 1st Spike Latency (CV) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AV | 11.74 (± 0.49) | 21.00 (±1.17) | 19.35 (± 0.82) | 0.338 (± 0.004) |

| CN | 9.44 (± 0.37) | 22.12 (± 0.90) | 19.37 (± 0.62) | 0.382 (± 0.008) |

| NV | 11.25 (± 0.53) | 23.55 (± 1.24) | 19.16 (± 0.73) | 0.377 (± 0.006) |

| Comparisons | ||||

| AV vs. CN | AV > CN * | AV < CN* | ns | AV < CN* |

| AV vs. NV | ns | AV < NV* | ns | AV < NV* |

| CN vs. NV | CN < NV* | CN < NV* | ns | ns |

Values are means (± se), computed over 50 dB range above tone threshold.

= statistically significant difference (p = 0.05 or less); ns = not significant

Peak Magnitude

Peak magnitude was normalized to standard scores (“z-scores”) to compensate for possible differences in background activity within subjects and across subjects and groups. The normalized magnitude of response was expressed as evoked spike rate divided by the standard deviation of background rate for each frequency/level (or noise/level) combination of stimulus parameters. Avoidance learning did not alter the magnitude of peak response. However, the magnitude of peak response was significantly less in the CN group than both the AV and NV groups (Figure 4B). The CN group peak magnitude is less than that of the AV group, across stimulus levels. Interestingly, it is also smaller than that of group NV. In contrast, there appears to be little difference between the response magnitudes of the avoidance and naïve subjects.

We again performed a nonlinear least-squares regression and modeled the peak magnitudes as an ascending exponential function of stimulus level:

Zmag = [U + (u · Group)] – [U + (u · Group) − L + (l · Group)] · [exp(−LEV)]β

This equation shares the same parameter and variable definitions as the descending exponential described above. Based on the fitted curves, the asymptotic response magnitudes (expressed as z-scores) for the AV, NV and CN groups were 11.7, 11.2, and 9.4, respectively. Applying the same extra sum of squares test described above, we found the response magnitudes of the control group to be significantly smaller than both experimental and naïve group magnitudes [CN vs. AV: F(2, 2431) = 33.0, p = 7.3 × 10−15; CN vs. NV: F(2, 2489) = 18.3, p = 1.3 × 10−8]. The response magnitudes of the experimental and naïve groups were not significantly different [AV vs. NV: F(2, 2635) = 1.51, p = 0.22] (Table 1).

Precision of Spike-Timing

Avoidance conditioning also improves spike-timing precision as indicated by reduced variability of 1st spike latencies (Figure 5A). The 1st spike latencies of groups AV and NV were not significantly different [AV vs. NV: F(2, 6572) = 0.21, p = 0.81]. Control-group clusters exhibited 1st spike latencies that were shorter at low stimulus levels, and longer at high stimulus levels. These differences, were statistically significant when compared against both the avoidance and naïve groups [CN vs. AV: F(2, 6000) = 4.7, p = 0.0087; CN vs. NV: F(2, 6261) = 3.1, p = 0.0465] (Table 1).

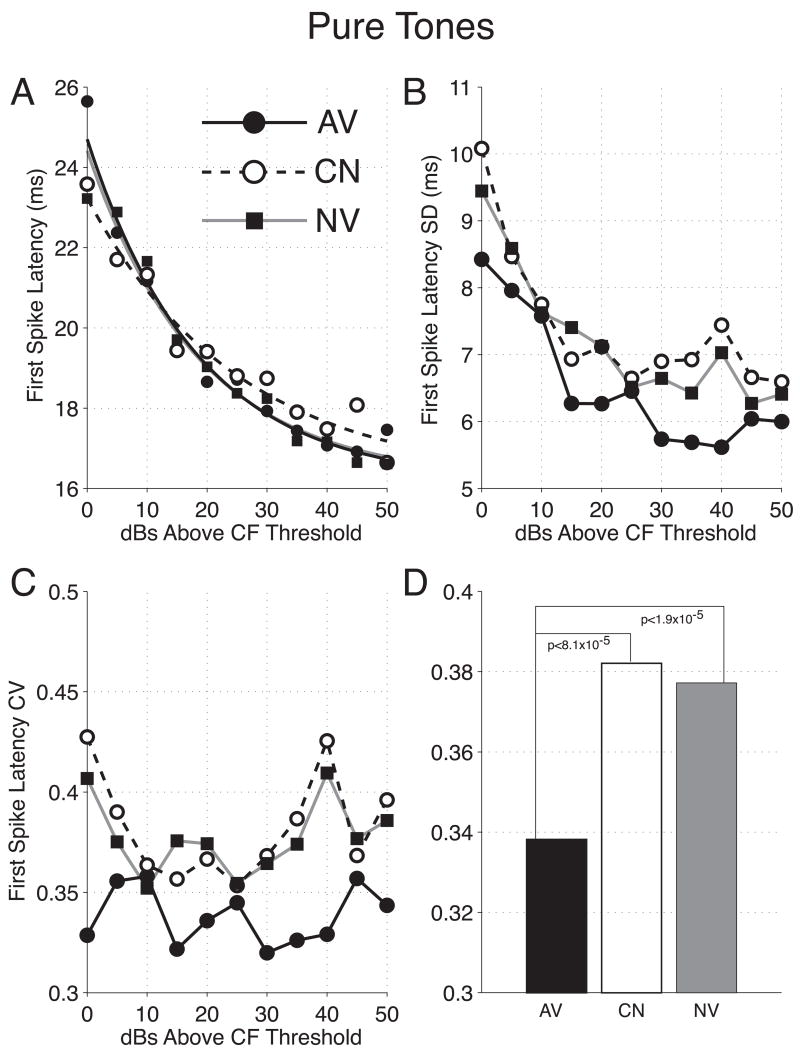

Figure 5.

The Effects of Behavioral Training on 1st Spikes Following Pure Tones. (A) 1st Spike Latencies vs. Stimulus Level. Avoidance training had no effect on the latency of the 1st spike. A small but statistically significant difference was detected for 1st spike latencies of group CN, such that latencies were slightly shorter at the lowest stimulus levels and slightly longer at the highest stimulus levels (p < 0.05 for both comparisons). (B–D) 1st Spike Latency Variability vs. Stimulus Level. For all three groups the standard deviation of 1st spike latencies declined as the stimulus level was increased (B). At all stimulus levels, the standard deviation (hence, variability) of latencies was lowest for the AV group. This was evident even when variability was expressed in terms of the coefficient of variation (C). When within-group CVs were pooled across stimulus level, those of group AV were found to be significantly lower than groups CN and NV (p < 0.05 for both comparisons; Bonferroni test). CVs for groups CN and NV did not differ significantly (D). AV = solid, CN = dashed, NV = gray for all graphs.

Consistent with previous studies (DeWeese, Wehr, & Zador, 2003; Heil, 1997), the variability (standard deviation) of 1st spike latencies was inversely related to stimulus level, i.e., reduced SD with higher level (Figure 5B). This relationship shows that reliability of response increases with increasing level. While this was true for all groups, standard deviations were lowest for the avoidance group, at all stimulus levels shown. Alternatively, the variability in 1st spike latencies may be expressed in terms of the coefficient of variation (CV; Figure 5C). The CV expresses the standard deviation as a ratio of the mean, thus yielding a measure of 1st spike latency variability independent of the mean latency. As a result, CVs can be pooled across stimulus levels and a single measure of variability can be expressed for each group (Figure 5D). The CVs among the three groups were significantly different [F(2, 30) = 15.8, p = 2.0 × 10−5]. The CV for the avoidance group (CV = 0.34 ± 0.01) was significantly lower than that of the naïve group (CV = 0.38 ± 0.01, p < 10−4) and the control group (CV = 0.38 ± 0.01, p < 10−5) (Bonferroni post-hoc). Naïve and control group CVs were not significantly different from each other (p > 0.05) (Table 1).

Effect of Avoidance Conditioning on CF Representation and Threshold

Analysis of the relationship between the tonotopic organization of A1 and group treatment would require complete frequency “maps”, which were not obtained in this study. However, the relative proportion of CFs across the frequency spectrum were analyzed, but we found no evidence of a greater proportion of CFs at or near the signal frequency of 8.0 kHz for group AV compared to groups CN and NV. Neither was there evidence of marked differential representation for any other frequency across groups. Overall, the frequency representations did not differ among groups (Kruskal–Wallace; χ2 = 0.24, p = 0.89).

Sensitivity to tones was also unaffected by behavioral training. This was determined by pooling all CF thresholds residing within the same bin among a set of equally spaced frequency bands. An analysis of variance revealed no significant differences in thresholds among the three groups at any CF bin (ANOVA for each of the 7 frequency bands, all p > 0.05). To control for the unlikely possibility that the threshold data were confounded by subtle consistent group differences of head location within the shuttlebox relative to the location of the fixed speaker, we then normalized all thresholds obtained for a given animal with respect to the average CF threshold for that subject. Again, statistical analysis revealed no significant differences in thresholds across the three groups at any CF bin (ANOVAs, all p > 0.05).

Effects of Training on A1 Responses to Noise

Responses to noise were determined to provide a more comprehensive account of sound processing after training. To enable comparison of responses to noise with responses to pure tone, the noise data were grouped according to the same range of stimulus levels used to group pure-tone responses (i.e., relative to CF threshold). In this way, at any given stimulus level, the noise and pure-tone responses at each level were obtained from the same recording sites. Of course, given cluster rather than single unit recordings, one cannot assume that the identical population of cells responded to tone and noise. In fact, being broadband by definition, noise would be expected to engage a wider range of neurons than pure tones at the same stimulus levels.

Peak-Latency

Avoidance conditioning affects the neural responses to pure-tone stimuli and noise in similar, although not identical, ways (Table 2, F Figure 6A). The noise peak latencies are also shortest for the avoidance group, ~2.0 ms shorter than naïve group latencies. And once again, the shock-matched control group exhibited reduced peak latencies by ~1.2 ms. Both these differences were significant [AV vs. NV: (2, 2685) = 15.5, p = 2.1 × 10−7; CN vs. NV: F(2, 2546) = 5.8, p = 0.0031. Peak latencies for the avoidance groups were ~0.8 ms shorter than the control group, this difference did not reach statistical significance: AV vs. CN: F(2, 2487) = 2.5, p = 0.0837]. However, latencies for AV were shorter than for CN for 9 of 11 stimulus levels above threshold, which is significant by the binomial test (p = 0.03, one-tailed) (Siegel & Castellan, 1988).

Table 2.

Responses to Noise

| Group | Peak Magnitude (z-scores) | Peak Latency (ms) | 1st Spike Latency (ms) | 1st Spike Latency (CV) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AV | 5.39 (± 0.50) | 22.68 (± 0.72) | 20.39 (± 0.44) | 0.351 (± 0.007) |

| CN | 4.84 (± 0.34) | 23.46 (± 0.69) | 19.55 (± 0.44) | 0.386 (± 0.004) |

| NV | 5.58 (± 0.58) | 24.68 (± 0.74) | 19.61 (± 0.41) | 0.397 (± 06) |

| Comparisons | ||||

| AV vs. CN | AV > CN * | ns | AV > CN* | AV < CN* |

| AV vs. NV | ns | AV < NV* | AV > NV* | AV < NV* |

| CN vs. NV | CN < NV* | CN < NV* | ns | ns |

Values are means (± se), computed over 50 dB range above tone threshold.

= statistically significant difference (p = 0.05 or less); ns = not significant

Figure 6.

The Effects of Behavioral Training on Peak Responses to Noise Bursts. (A) Peak Latencies vs. Stimulus Level. As for pure tones, peak latencies for noise bursts were determined from average spike rates (bin-width = 3 ms) measured for the first 60 ms after burst onset. Again, neural clusters recorded from avoidance rats (AV = solid) showed significantly reduced peak latencies relative to both naïve (NV = gray) and control (CN = dashed) groups (AV vs. NV: p < 10−6, F-test; AV vs. CN: p = 0.033, binomial test). Likewise, peak latencies for group CN were also significantly shorter than group NV (p < 0.002). (B) Peak Magnitudes vs. Stimulus Level. As for pure tones avoidance training had no effect on the magnitude of the peak response to noise bursts. However, group CN exhibited significantly smaller peak magnitudes relative to groups AV and NV (p < 10−3 for both comparisons). Peak magnitudes for noise were normalized by the same procedure applied to pure tone data (see Figure 4 legend). AV = solid, CN = dashed, NV = gray.

Peak Magnitude

Additionally, as with pure-tones, the noise response magnitudes of the control group were significantly smaller than the naïve and avoidance groups [CN vs. AV: F(2, 2486) = 7.2, p = 8.0 × 10−4; CN vs. NV: F(2, 2545) = 12.3, p = 4.8 × 10−6]. And once again, the latter two groups were statistically indistinguishable [AV vs. NV, F(2, 2684) = 0.70, p = 0.49] (Figure 6B).

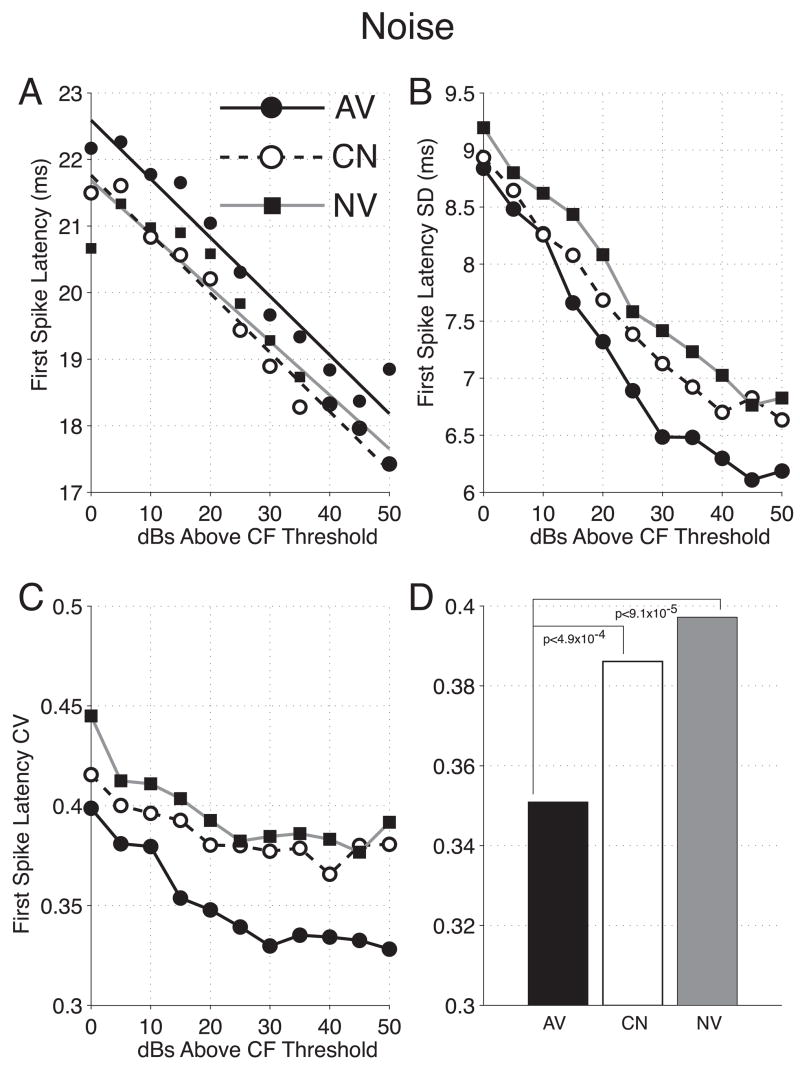

Precision of Spike-Timing

Analysis of 1st spike latencies to noise produced results similar to pure-tone data (Table 2). There was one exception. Across stimulus levels the 1st spike latencies obtained for the avoidance group were significantly longer than naïve and control group latencies, albeit, by less than a millisecond [CN vs. AV: F(2, 34994) = 39.9, p < 10−6; NV vs. AV: F(2, 32455) = 52.6, p < 10−6] (Figure 7A). Nonetheless, the variability of 1st spike latencies was again different among groups [F(2, 30) = 16.3, p = 1.6 × 10−5] (Figure 7B). The mean CV was significantly smaller for the avoidance group compared to both the control and naïve group latencies (p < 0.05, respectively; Bonferroni tests). CVs for control and naïve groups did not differ significantly (p > 0.05, Bonferroni) (Figures 7C,D).

Figure 7.

The Effects of Behavioral Training on 1st Spikes Following Noise Bursts. (A) 1st Spike Latencies vs. Stimulus Level. Across stimulus levels avoidance training appeared to increase 1st spike latencies by ~1 ms, relative to both CN and NV groups (p < 10−5 for both comparisons). Latencies for CN and NV were statistically indistinguishable. (B–D) 1st Spike Latency Variability vs. Stimulus Level. The variability of 1st spike latencies to noise bursts is represented here as it was for pure tone data (see Figure 5B–D). Once again, CVs pooled across stimulus levels were significantly reduced for group AV, relative to both CN and NV groups (p < 0.05 for both comparisons; Bonferroni test). Again, CVs for groups CN and NV did not differ significantly (D). AV = solid, CN = dashed, NV = gray for all graphs.

DISCUSSION

Neurons in the primary auditory cortex exhibit shorter peak response latencies and reduced variability of 1st spike latencies in animals that have learned to perform an auditory avoidance task. These learning-induced changes in cortical processing developed in the absence of changes in either the magnitude or the threshold of response. This contrasts with prior studies in which the magnitude of response to the CS in A1 was specifically increased (Bakin et al., 1996; Bakin & Weinberger, 1990; Bao, Chan, & Merzenich, 2001; Bao et al., 2004; Beitel et al., 2003; Blake, Heiser, Caywood, & Merzenich, 2006; Blake, Strata, Churchland, & Merzenich, 2002; Edeline & Neuenschwander-el Massioui, 1988; Edeline, Pham, & Weinberger, 1993; Edeline & Weinberger, 1993; Galván & Weinberger, 2002; Gao & Suga, 2000; Ji, Gao, & Suga, 2001; Ji & Suga, 2003; Kisley & Gerstein, 2001; Polley et al., 2004, 2006; Weinberger, Javid, & Lepan, 1993). Thus, the particular parameters of learning-induced plasticity are not tightly-linked but may be task-dependent (Ohl & Scheich, 2005).

Although prior direct studies of latency facilitation in learning-related auditory cortical plasticity are rare, a recent study of “auditory enrichment” did report a reduction in peak latency in rats that lived in a complex auditory environment (Engineer, Percaccio, Pandya, Moucha, Rathbun, & Kilgard, 2004). However, in addition to hearing many different sounds and musical selections, the rats also were subjected to both Pavlovian and instrumental reward contingencies following sound presentation as they moved through group cages containing many objects. Therefore, the facilitation of peak latency might have been due either or both to enrichment per se and classical and/or instrumental learning.

Lack of Frequency Specificity in Facilitation of Temporal Processing

There was no indication that changes in response magnitude or facilitation of temporal processing were preferentially related to the avoidance training frequency of 8.0 kHz, or even to its neighboring frequencies. Temporal plasticity was equally evident for all pure-tones that were tested and for noise, despite only training with tone. The avoidance facilitation averaged 2.6 ms for tones and about 2.0 ms for noise, compared to naïve subjects. Lack of frequency-specificity in plasticity of temporal processing is consistent with the notion that animals failed to learn about tone frequency. This would come as no surprise given that successful shock avoidance merely required animals to detect the occurrence of an auditory signal, as opposed to a tone of specific frequency. Moreover, failure to learn about tone per se might be expected in the absence of discrimination training (Mackintosh, 1974). Post-training stimulus generalization tests should be used in further studies to resolve this issue.

Another possible explanation for our inability to find a frequency-specific facilitation of temporal processing is the lack of appropriate frequency data. Unlike prior studies, frequency receptive fields (tuning functions) were not obtained within subjects before and after training, an approach that is highly sensitive (reviewed in Weinberger, 2004). Neither did this study include the determination of complete tonotopic “maps”, which necessitate high density sampling of the auditory cortex across A1. Frequency analysis relied on calculating the probability distribution of obtaining best tuning (CFs) across acoustic frequency. These data revealed no difference among groups. It is possible, although unlikely, that the sampling of A1 was inadvertently biased across groups, although it did cover the low to high frequency range. Thus, if there had been an expansion of 8.0 kHz representation but the region involved had been under-sampled in group AV, then any relative increase in the number of sites that became tuned to 8.0 kHz would have been missed.

Whether the stimulus frequency was processed or simply ignored, there is little doubt that the tone stimulus was deemed behaviorally relevant to avoidance animals. First, group AV did learn the avoidance response, and did so to a high level (Figure 2A). Second, the increase in the percentage of avoidance responses represents genuine learning, rather than putative increasing sensitization to tone due to the presence of shock because group CN, which received unpaired tone and shock, did not exhibit a similar learning function. Third, the behavioral differences between AV and CN subjects cannot be attributed to differential shock density because the groups were matched for the number of shocks (Figure 2B). Fourth, the lack of learning in group CN was not due to a putative deficit in the ability to escape shock, and thus inability to learn the avoidance response, because their escape latencies were similar to those of the AV subjects in showing faster escapes from session 1 to session 2 and thereafter (Figure 2C). These findings suggest some learning of escape behavior in both groups. Of interest, CN escape latencies were slightly longer than AV latencies. This may reflect the advantage of the warning tone in group AV, permitting subjects to escape faster on those trials in which their incipient avoidance responses were not quite fast enough.

Reduction of Response Magnitude in Control-Trained Group

The finding that the shock-matched control group exhibited the lowest peak response magnitudes, in addition to a modest reduction in peak latencies, appears to be at odds with the tone’s lack of behavioral relevance in this task. One possibility is that the mere exposure to shock or learning to escape shock mediated the observed plasticity, by way of its effect on arousal. This notion seems very unlikely, given that neural responses were measured under general anesthesia, when arousal is a non-factor. A future study employing a “shock-only” group may help to resolve this issue. Another possibility is that the plasticity in the control group was due solely to tone exposure, such that shocks had no effect. This explanation is tantamount to one involving simple habituation. Neural responses to tones are reduced following their repeated presentation (Condon & Weinberger, 1991; Edeline & Weinberger, 1993), however the effect of habituation on temporal processing is less understood. Future studies which incorporate tone-only or shock-only control groups are needed to further explore these issues.

An alternative, and more viable, explanation is that the tone served as a “safety signal” (i.e., inhibitory conditioned stimulus) for control animals, informing them that a shock would not occur for at least twenty seconds following the tone’s offset. This interpretation is consistent with prior evidence that A1 neurons reduce their responsiveness to acoustic stimuli that signal the absence of an aversive event (Edeline & Weinberger, 1993). The reduction in peak latency for the control group, while significant relative to untrained animals, was less than the reduction for the avoidance group, particularly for tones. Thus, the temporal plasticity for an excitatory signal (group AV) may be generally greater than for an inhibitory signal (group CN). Whether or not this proves to be the case in future studies that are designed to specifically address the issue of inhibitory conditioning, the finding that temporal plasticity is not restricted to excitatory signals is noteworthy.

Auditory Learning and Plasticity of Temporal Processing

The principles that govern the particular form of cortical plasticity remain to be elucidated and probably cannot be systematically approached until a much larger base of learning-related findings becomes available. This need seems particularly acute in the case of plasticity of temporal parameters due to their paucity and lack of consistency. For example, while employing auditory discrimination procedures Recanzone et al. (1993) reported an increase in first spike latencies in owl monkeys, whereas Brown et al. (2004), using cats, reported decreases. In the present study, avoidance conditioning increased the average latency of the first-spike following broadband noise but not a pure tone stimulus, yet the variability of latency was reduced in both cases. Neither of the two studies cited above addressed first spike latency variability, so it remains to be seen whether auditory learning affects spike timing precision in a more consistent manner than it does the average time of spike onset.

One recent study examined whether neurons are selective for species-specific vocalizations in the ferret (Schnupp, Hall, Kokelaar, & Ahmed, 2006). The responses of single cell clusters in A1 (as used in our study of avoidance) were analyzed for responses to three forms of marmoset twitter calls (Wang and Kadia, 2001) and a variety of calls from several other taxa. Although rate-coding failed to discriminate among the stimuli, the temporal patterns of responses (over sampling bins of ~20–50 ms) did yield measures of “Shannon mutual information” which were discriminative. Of particular interest, two ferrets trained to discriminate between marmoset twitter calls and the variety of other vocalizations yielded significantly greater amounts of mutual information. Thus, learning can increase the amount of information contained in temporal patterns of response. Unfortunately, these findings are difficult to relate to the present results because of substantial differences between studies. Thus, the Schnupp et al. experiments trained ferrets in a difficult, and ultimately categorical, discrimination for water reward over periods ranging from 140 to 260 days, entailing many thousands of trials. Our subjects were trained in a single tone, non-discriminative, avoidance task for only 5–7 days. The amount and type of training may be important for increasing the amount of information in temporal patterns of response and should be studied in the future.

Acknowledgments

We thank Gabriel K. Hui and Jacquie Weinberger for assistance. This research was supported by a research grant from the National Institutes of Health/National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (NIDCD) DC-02938 to N.M.W.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Bakin JS, South DA, Weinberger NM. Induction of receptive field plasticity in the auditory cortex of the guinea pig during instrumental avoidance conditioning. Behavioral Neuroscience. 1996;110(5):905–913. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.110.5.905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakin JS, Weinberger NM. Classical conditioning induces CS-specific receptive field plasticity in the auditory cortex of the guinea pig. Brain Research. 1990;536(1–2):271–286. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)90035-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao S, Chan VT, Merzenich MM. Cortical remodelling induced by activity of ventral tegmental dopamine neurons. Nature. 2001;412(6842):79–83. doi: 10.1038/35083586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao S, Chang EF, Woods J, Merzenich MM. Temporal plasticity in the primary auditory cortex induced by operant perceptual learning. Nature Neuroscience. 2004;7(9):974–981. doi: 10.1038/nn1293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beitel RE, Schreiner CE, Cheung SW, Wang X, Merzenich MM. Reward-dependent plasticity in the primary auditory cortex of adult monkeys trained to discriminate temporally modulated signals. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2003;100(19):11070–11075. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1334187100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake DT, Heiser MA, Caywood M, Merzenich MM. Experience-Dependent Adult Cortical Plasticity Requires Cognitive Association between Sensation and Reward. Neuron. 2006;52(2):371–381. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake DT, Strata F, Churchland AK, Merzenich MM. Neural correlates of instrumental learning in primary auditory cortex. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2002;99(15):10114–10119. doi: 10.1073/pnas.092278099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown M, Irvine DR, Park VN. Perceptual learning on an auditory frequency discrimination task by cats: Association with changes in primary auditory cortex. Cerebral Cortex. 2004;14(9):952–965. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhh056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Condon CD, Weinberger NM. Habituation produces frequency-specific plasticity of receptive fields in the auditory cortex. Behavioral Neuroscience. 1991;105(3):416–430. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.105.3.416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delay ER, Rudolph TL. Crossmodal training reduces behavioral deficits in rats after either auditory or visual cortex lesions. Physiology and Behavior. 1994;55(2):293–300. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(94)90136-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeWeese MR, Wehr M, Zador AM. Binary spiking in auditory cortex. Journal of Neuroscience. 2003;23(21):7940–7949. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-21-07940.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond DM, Weinberger NM. Classical conditioning rapidly induces specific changes in frequency receptive fields of single neurons in secondary and ventral ectosylvian auditory cortical fields. Brain Research. 1986;372(2):357–360. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(86)91144-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond ME, Petersen RS, Harris JA. Learning through maps: Functional significance of topographic organization in primary sensory cortex. Journal of Neurobiology. 1999;41(1):64–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doron NN, LeDoux JE, Semple MN. Redefining the tonotopic core of rat auditory cortex: Physiological evidence for a posterior field. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 2002;453(4):345–360. doi: 10.1002/cne.10412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Draper NR, Smith H. Applied Regression Analysis. 3. New York: John Wiley and Sons; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Duvel AD, Smith DM, Talk A, Gabriel M. Medial geniculate, amygdalar and cingulate cortical training-induced neuronal activity during discriminative avoidance learning in rabbits with auditory cortical lesions. Journal of Neuroscience. 2001;21(9):3271–3281. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-09-03271.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edeline J-M. Learning-induced plasticity in the thalamo-cortical auditory system: Should we move from rate code to temporal code descriptions? In: König R, Heil P, Budinger E, Scheich H, editors. The Auditory Cortex: A Synthesis of Human and Animal Research. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2005. pp. 365–382. [Google Scholar]

- Edeline JM, Neuenschwander-el Massioui N. Retention of CS–US association learned under ketamine anesthesia. Brain Research. 1988;457(2):274–280. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(88)90696-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edeline JM, Pham P, Weinberger NM. Rapid development of learning-induced receptive field plasticity in the auditory cortex. Behavioral Neuroscience. 1993;107(4):539–551. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.107.4.539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edeline JM, Weinberger NM. Receptive field plasticity in the auditory cortex during frequency discrimination training: Selective retuning independent of task difficulty. Behavioral Neuroscience. 1993;107(1):82–103. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.107.1.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engineer ND, Percaccio CR, Pandya PK, Moucha R, Rathbun DL, Kilgard MP. Environmental enrichment improves response strength, threshold, selectivity, and latency of auditory cortex neurons. Journal of Physiology. 2004;92(1):73–82. doi: 10.1152/jn.00059.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabriel M, Saltwick SE, Miller JD. Conditioning and reversal of short-latency multiple-unit responses in the rabbit medial geniculate nucleus. Science. 1975;189(4208):1108–1109. doi: 10.1126/science.1162365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galván VV, Weinberger NM. Long-term consolidation and retention of learning-induced tuning plasticity in the auditory cortex of the guinea pig. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory. 2002;77(1):78–108. doi: 10.1006/nlme.2001.4044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao E, Suga N. Experience-dependent plasticity in the auditory cortex and the inferior colliculus of bats: Role of the corticofugal system. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2000;97(14):8081–8086. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.14.8081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert CD, Sigman M, Crist RE. The neural basis of perceptual learning. Neuron. 2001;31(5):681–697. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00424-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Lima F, Scheich H. Neural substrates for tone-conditioned bradycardia demonstrated with 2-deoxyglucose. I. Activation of auditory nuclei. Behavioural Brain Research. 1984;14(3):213–233. doi: 10.1016/0166-4328(84)90190-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Lima F, Scheich H. Neural substrates for tone-conditioned bradycardia demonstrated with 2-deoxyglucose. II. Auditory cortex plasticity. Behavioural Brain Research. 1986;20(3):281–293. doi: 10.1016/0166-4328(86)90228-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heil P. Auditory cortical onset responses revisited. I. First-spike timing. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1997;77(5):2616–2641. doi: 10.1152/jn.1997.77.5.2616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horikawa J, Ito S, Hosokawa Y, Homma T, Murata K. Tonotopic representation in the rat auditory cortex. Proceedings of the Japan Academy: Series B. 1988;64(8):260–263. [Google Scholar]

- Ji W, Gao E, Suga N. Effects of acetylcholine and atropine on plasticity of central auditory neurons caused by conditioning in bats. Journal of Neurophysiology. 2001;86(1):211–225. doi: 10.1152/jn.2001.86.1.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji W, Suga N. Development of reorganization of the auditory cortex caused by fear conditioning: Effect of atropine. Journal of Neurophysiology. 2003;90(3):1904–1909. doi: 10.1152/jn.00363.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kisley MA, Gerstein GL. Daily variation and appetitive conditioning-induced plasticity of auditory cortex receptive fields. European Journal of Neuroscience. 2001;13(10):1993–2003. doi: 10.1046/j.0953-816x.2001.01568.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackintosh NJ. Psychology of Animal Learning. New York: Academic Press; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Merzenich MM, Sameshima K. Cortical plasticity and memory. Current Opinion in Neurobiology. 1993;3(2):187–196. doi: 10.1016/0959-4388(93)90209-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris JS, Friston KJ, Dolan RJ. Experience-dependent modulation of tonotopic neural responses in human auditory cortex. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London: Series B. 1998;265(1397):649–657. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1998.0343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohl FW, Scheich H. Learning-induced plasticity in animal and human auditory cortex. Current Opinion in Neurobiology. 2005;15(4):470–477. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2005.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer CV, Nelson CT, Lindley GA., 4th The functionally and physiologically plastic adult auditory system. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 1998;103(4):1705–1721. doi: 10.1121/1.421050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polley DB, Heiser MA, Blake DT, Schreiner CE, Merzenich MM. Associative learning shapes the neural code for stimulus magnitude in primary auditory cortex. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2004;101(46):16351–16356. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407586101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polley DB, Steinberg EE, Merzenich MM. Perceptual learning directs auditory cortical map reorganization through top-down influences. Journal of Neuroscience. 2006;26(18):4970–4982. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3771-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rauschecker JP. Auditory cortical plasticity: a comparison with other sensory systems. Trends in Neurosciences. 1999;22(2):74–80. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(98)01303-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Recanzone GH, Schreiner CE, Merzenich MM. Plasticity in the frequency representation of primary auditory cortex following discrimination training in adult owl monkeys. Journal of Neuroscience. 1993;13(1):87–103. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-01-00087.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutkowski RG, Miasnikov AA, Weinberger NM. Characterisation of multiple physiological fields within the anatomical core of rat auditory cortex. Hearing Research. 2003;181(1–2):116–130. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(03)00182-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutkowski RG, Weinberger NM. Encoding of learned importance of sound by magnitude of representational area in primary auditory cortex. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2005;102(38):13664–13669. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506838102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sally SL, Kelly JB. Organization of auditory cortex in the albino rat: Sound frequency. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1988;59(5):1627–1638. doi: 10.1152/jn.1988.59.5.1627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scharlock DP, Miller MH. Negative stimulus duration as a factor in frequency discrimination by cats lacking auditory cortex. Perceptual and Motor Skills. 1964;18:9–10. doi: 10.2466/pms.1964.18.1.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheich H, Stark H, Zuschratter W, Ohl FW, Simonis CE. Some functions of primary auditory cortex in learning and memory formation. Advances in Neurology. 1997;73:179–193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnupp JW, Hall TM, Kokelaar RF, Ahmed B. Plasticity of temporal pattern codes for vocalization stimuli in primary auditory cortex. Journal of Neuroscience. 2006;26(18):4785–4795. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4330-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel S, Castellan NJ., Jr . Nonparametric Statistics for the Behavioral Sciences. 2. New York: McGraw–Hill; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Kadia SC. Differential representation of species-specific primate vocalizations in the auditory cortices of marmoset and cat. Journal of Neurophysiology. 2001;86(5):2616–2620. doi: 10.1152/jn.2001.86.5.2616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberger NM. Dynamic regulation of receptive fields and maps in the adult sensory cortex. Annual Review of Neuroscience. 1995;18:129–158. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.18.030195.001021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberger NM. Physiological memory in primary auditory cortex: Characteristics and mechanisms. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory. 1998;70(1–2):226–251. doi: 10.1006/nlme.1998.3850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberger NM. Experience-dependent response plasticity in the auditory cortex: Issues, characteristics, mechanisms and functions. In: Parks TN, Rubel EW, Fay RR, Popper AN, editors. Plasticity of the Auditory System. New York: Springer–Verlag; 2004. pp. 173–227. [Google Scholar]

- Weinberger NM, Diamond DM. Physiological plasticity in auditory cortex: Rapid induction by learning. Progress in Neurobiology. 1987;29(1):1–55. doi: 10.1016/0301-0082(87)90014-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberger NM, Diamond DM, McKenna TM. Initial events in conditioning: Plasticity in the pupillomotor and auditory system. In: Lynch G, McGaugh JL, Weinberger NM, editors. Neurobiology of Learn ing and Memory. New York: Guilford Press; 1984. pp. 197–227. [Google Scholar]

- Weinberger NM, Javid R, Lepan B. Long-term retention of learning-induced receptive-field plasticity in the auditory cortex. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1993;90(6):2394–2398. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.6.2394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]