Abstract

The proteasome regulates diverse intracellular processes, including cell-cycle progression, antigen presentation, and inflammatory response. Selective inhibitors of the proteasome have great therapeutic potential for the treatment of cancer and inflammatory disorders. Natural cyclic peptides TMC-95A and B represent a new class of noncovalent, selective proteasome inhibitors. To explore the structure-activity relationship of this class of proteasome inhibitors, a series of TMC-95A/B analogues were prepared and analyzed. We found that the unique enamide functionality at the C-8 position of TMC-95s can be replaced with a simple allylamide. The asymmetric center at C-36 that distinguishes TMC-95A from TMC-95B but which necessitates a complicated separation of the two compounds can be eliminated. Therefore, these findings could lead to the development of more accessible simple analogues as potential therapeutic agents.

Keywords: inhibitors, peptides, proteasome, synthesis, structure-activity relationships

Introduction

In eukaryotic cells, proteins are degraded predominantly by the ubiquitin proteasome pathway.[1,2] The central enzyme of this process, the 26S proteasome, is a multicatalytic protease complex found in both the cytosol and the nucleus. In this pathway, targeted proteins are first marked by covalent attachment with a polyubiquitin chain.[3] The subsequent degradation by the proteasome requires adenosine triphosphate (ATP) hydrolysis, which indicates that the 26S proteasome is a eukaryotic ATP-dependent protease.[4,5] This enzyme consists of a 20S proteolytic core particle and a 19S regulatory subunit at either one or both ends.[6] The 19S complex is responsible for binding and removal of the ubiquitin chain and unfolding and translocation of the proteins to the 20S particle for degradation.[6] The 20S core complex is a barrel-shaped structure composed of four stacked multiprotein rings.[7#x02013;9] Each of the two central β rings contains three active proteolytic sites that function together to hydrolyze the proteins into small peptides. These active sites differ in their specificities: one cleaves preferentially after hydrophobic residues, one after basic residues, and one after acidic residues. Accordingly, the sites are called chymotrypsin-like (CT-L), trypsin-like (TL), and postglutamyl peptide hydrolytic (PGPH) sites, respectively.[10–12] The proteolytic sites in the 20S proteasome function by utilizing an amino-terminal threonine of the β subunits as the catalytic nucleophile.[6]

The proteasome is not only responsible for the removal of damaged or misfolded proteins, but also for processing and degrading regulatory proteins that control many diverse cellular processes, including cell-cycle progression, apoptosis, and NF-κB activation.[4,13] A small fraction of the peptides generated by the proteasome are presented by major histocompatibility complex class I molecules on the cell surface, and thus play a role in immune surveillance.[14–17] Therefore, inhibitors that selectively block proteolytic activities of the proteasome are of therapeutic potential for the treatment of cancer, inflammatory disorders, and immune diseases.[18–20] Many proteasome inhibitors have been developed, such as synthetic peptide aldehydes,[1] boronates,[21] or vinylsulfones,[22] as well as the natural products lactacystin[23] and epoxomicin.[24] All of these inhibitors function through covalent modification of the N-terminal threonine residue of β subunits.[18, 19] Among them, PS-341,[25] a dipeptide boronate, has entered Phase II and Phase III trials as a drug against various cancers. Selective inhibitors of the proteasome show great promise as novel anticancer agents since tumor cells are more sensitive than normal cells to proteasome-inhibition-induced apoptosis.[26–28]

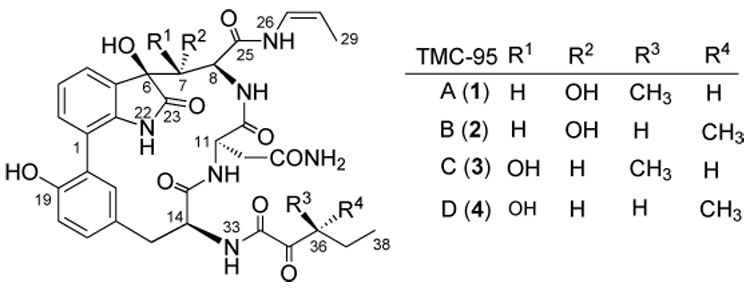

TMC-95A (1) and its diastereoisomers TMC-95B – D(2 – 4), recently isolated as fermentation products of Apiospora montagnei,[29] represent a new class of selective proteasome inhibitors (Scheme 1). These molecules are structurally characterized as novel cyclic peptides containing l-tyrosine, l-asparagine, highly oxidized l-tryptophan, (Z)-1-propenylamine (Z=benzyloxycarbonyl), and 3-methyl-2-oxopentanoic acid moieties.[30] Biological studies[29] showed that TMC-95A inhibited the CT-L, TL, and PGPH activities of 20S proteasome with IC50 values (IC50=concentration required for 50% inhibition) of 5.4, 200, and 60nm, respectively. TMC-95B inhibited these activities to the same extent as TMC-95A, while TMC-95C and D were 20 – 150 times weaker inhibitors. TMC-95A did not inhibit m-calpain, cathepsin L, or trypsin at 30 µm, which suggests it has high selectivity for the proteasome. The binding mode of these inhibitors has been recently elucidated by X-ray crystallography.[31] Unlike other proteasome inhibitors, TMC-95A does not modify the N-terminal catalytic threonine residue. It binds to all three active sites of the proteasome through characteristic hydrogen bonds. TMC-95A also has cytotoxic activity against human cancer cells HCT-116 and HL-60, with IC50 values of 4.4 µm and 9.8 µm, respectively.[29]

Scheme 1.

Structures of TMC-95s.

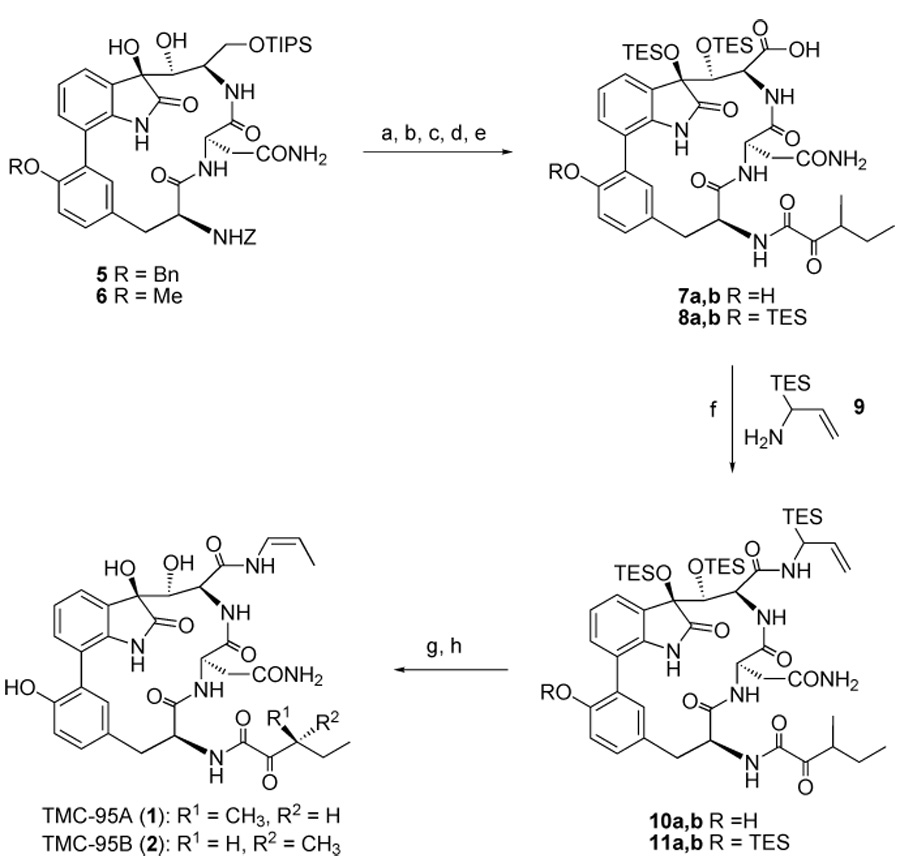

The combination of structural novelty, potency, and the unique inhibition mechanism of TMC-95A and B led us to undertake a program of total synthesis directed towards this family of metabolites. Recently, our laboratory reported the first total synthesis of TMC-95A and B.[32] However, several structural features of these molecules have rendered our current synthesis impractical for producing amounts of materials appropriate for clinical follow-up. Besides a strained 17-membered heterocycle, whose efficient construction remains a challenge, these molecules also contain a rich diversity of vulnerable functionalities, particularly in the extended “pyruvolyl”-like (C-34 – C-38) and dihydroxyindolinone (positions 22, 23, and 6 – 8) sections. A notable feature of the synthesis is the installation of the cis-enamide (C-25 – C-29) functionality by a novel rearrangement of α-silylallyl amide precursors (10a,b and 11 a,b) at a very late stage (Scheme 2). As a result of the presence of sensitive groups on the molecules, multiple steps are required to execute the transformation of protected alcohol precursor 5 into the final targets (Scheme 2). We began to explore the structure-activity relationship of the proteasome inhibitors derived from TMC-95A and B. Our goal was to develop simpler and more accessible TMC-95A/B analogues for broad biological evaluation. We hoped to accomplish this by modification of the protocols used in the total synthesis such as to bypass the most difficult transformations. Clearly, the question was whether biological function would be retained by such congeners. If so, valuable proteasome-directed agents might become much more accessible. For instance, we hoped that function could be maintained even with modification of the enamide function at C-8 and the ketoamide section at C-36. A series of analogues was indeed obtained and their inhibition against proteolytic activities of the 20S proteasome was evaluated. We found that some of the simplified analogues retained potent proteasome inhibitory activity.

Scheme 2.

Final steps in the synthesis of TMC-95A and B. Reagents and conditions: a) Pd/C, H2, EtOH, RT, 19 h; b) (+)-3-methyl-2-oxopentanoic acid, EDC/HOAT, CH2Cl2/DMF, RT, 2 h, 0°C → RT, 2 h, 85% (two steps); c) HF/Py; d) TESOTf, 2,6-lutidine, CH2Cl2, 0°C → RT, 15 h; then NaHCO3 ; then citric acid, EtOAc/H2O; e) Jones reagent, acetone, 0 °C, 2 h; f) 9, EDC/HOAT, CH2Cl2/DMF, RT, 13 h, 33% (four steps); g) o-xylene, 140 °C, 3 d; then H2O; h) HF/Py, THF/Py; then Me3SiOMe, 49% (two steps). Bn, benzyl; TIPS, triisopropylsilyl, TES, trimethylsilyl; Tf, trifluoromethanesulfonyl; EDC, 1-[3-(dimethylamino)propyl]-3-ethylcarbodiimide hydrochloride; HOAT, 1-hydroxyl-7-azabenzotriazole; DMF, N,N-dimethylformamide; THF, tetrahydrofuran; Py, pyridine.

Results

Design of TMC-95A/B analogues

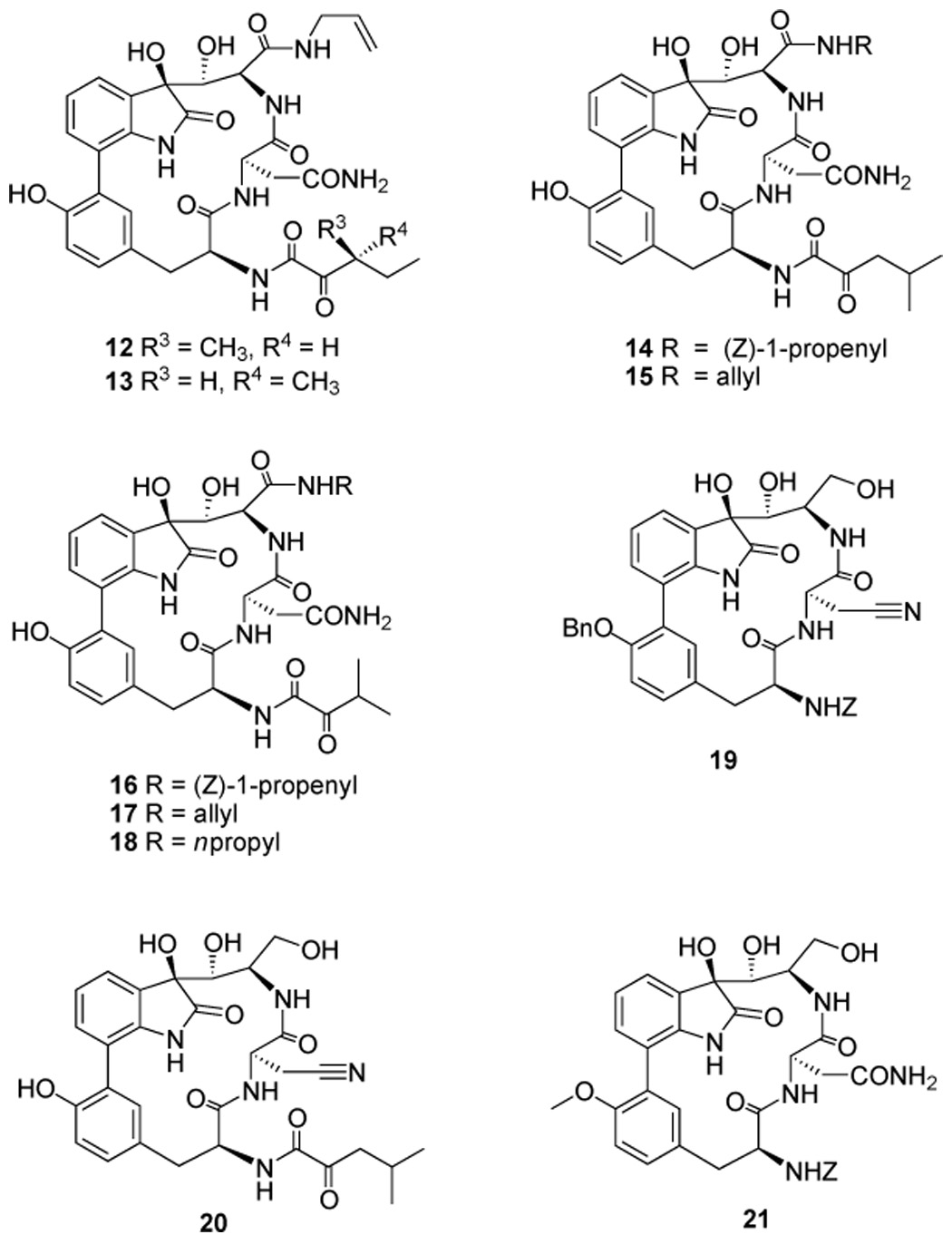

The four TMC-95s are diastereoisomers with asymmetric centers at C-7 and C-36. TMC-95A and B differ only in the configuration of the methyl group at the C-36 position, but share identical biological activities.[29] This finding suggested to us that the C-36 asymmetric center might have little effect on activity. In contrast, the stereochemistry of the hydroxy group at the C-7 position can influence the activity by up to two orders of magnitude.[29] Recently, it was found that a simplified analogue lacking this hydroxy group is 150 times less potent against CT-L activity of the proteasome than the unmodified molecule.[33] The crystal structure of the 20S proteasome–TMC-95A complex anticipated these in vitro findings and provided the structural basis for this new class of noncovalent, reversible inhibitors.[31] The structure suggests that the cis-propylene group and the side chain of the asparagine residue, which interact with the S1 and S3 pockets of the proteasome, respectively, provide most of the specific interactions. In addition, the rigid biaryl-linked heterocyclic conformation of TMC-95s appears suitable for optimal binding to the proteasome for entropic reasons. TMC-95A and B block all three active sites but show only moderate selectivity for CT-L activity.[29] These results suggested to us that it might be possible to design potent and subunit-selective inhibitors through optimization of the two groups that bind the S1 and S3 pockets. Since the installation of the enamide group from an alcohol precursor involves multiple steps with low yields, we first chose to modify this position. The allylamide derivatives (12 and 13, respectively, Scheme 3) are two analogues that are closely related to TMC-95A and B, but are considerably more accessible. Initially, the two compounds were generated from the side-products of the enamide formation reaction. However, these compounds can be synthesized by directly coupling carboxylic acids 7a,b and 8a,b with allylamine, followed by deprotection. The syntheses of these compounds are much more straightforward than those of the parent compounds TMC-95A and B.

Scheme 3.

Structures of designed TMC-95A analogues.

In a similar vein, the C-36 asymmetric center on the ketoamide side chain contributes little to potency but necessitates the problematic separation of TMC-95A and B. Therefore, we chose to eliminate this source of stereogenicity. Accordingly, two analogues (14 and 16, Scheme 3), each bearing a symmetric ketoamide side chain, were prepared. The corresponding allylamide derivatives (15 and 17, Scheme 3) were also generated for evaluation. To further explore the optimal binding groups for the proteasomal S1 pocket, compound 18 (Scheme 3), which has a more flexible propyl group instead of cis-propylene at the C-8 position, was synthesized. If this compound were found to be active, we anticipated that an alternative, far more direct and concise route to the target system could be developed. In this way, a simpler amide side chain at C-8 would be installed at an early stage of the synthesis.

We also prepared analogues 19 – 21, each of which has an alcohol side chain in place of an enamide (Scheme 3). These compounds were designed to markedly reduce the complexity of the synthesis. Specifically, compounds 19 and 20 were generated from a C-11 nitrile analogue of 5, which is produced as a result of dehydration of the asparagine side chain. Removal of the silyl group of 6 afforded compound 21. Both 19 and 21 contain a benzylcarbamate protecting group at the C-14 position. Compound 19 contains a benzyl-protected tyrosine hydroxy group at the C-19 position, while triol 21 has a smaller methyl group at that position. The tyrosine residue of TMC-95s fills the S4 pocket of the proteasome and forms nonpolar interactions with the active sites.[31]

Proteasome inhibition studies

To establish a preliminary structure–activity relationship (SAR) profile of TMC-95A and B, we evaluated the biological activities of our synthetic analogues on purified bovine erythrocyte proteasome. We assessed the rates of proteolytic inactivation achieved by the compounds that fit the profile of slow-binding inhibitors. For these inhibitors, the rates of inhibition, kassociation (kobs/[I]; kobs = apparent rate constant for a time-dependent inhibition, [I] = inhibitor concentration) were determined by using fluorogenic peptide substrates and a range of inhibitor concentrations (Table 1). We also determined the inhibition constants (Kiapp values) for all the TMC-95 compounds (Table 2) to compare their relative potency. Compounds 12 and 13, allylamide derivatives of TMC-95A or B, retained full activity and were found to inhibit all proteolytic activities of the proteasome. Compounds 14 and 16, both containing a non-stereogenic ketoamide side chain at C-14, also exhibit the same potency as the natural products. As expected, compounds 15 and 17, the allylamide analogues of 14 and 16, retain potent proteasome inhibitory activity. However, compound 18, generated by modification of the enamide group of 16 with a propylamide, was found to be ten times less active than 16. Interestingly, all of the enamide-containing compounds tested (1, 2, 14, and 16) behave as slow-binding inhibitors for both CT-L and PGPH activities. These compounds inhibit the chymotrypsinl-ike activity of the 20S proteasome most potently with kassociation values of 190000 – 720000 m−1 s−1. These rates of inactivation are 4- to 15-fold faster than that of epoxomicin and slightly faster than the rate achieved by the corresponding reversible inhibitor, epoxomicin aldehyde. However, unlike epoxomicin derivatives, none of the inhibitors derived from TMC-95s display slow-binding inhibition against trypsin-like activity.

Table 1.

Rates of inhibition of proteasome catalytic activities by slow-binding inhibitors.[a]

| kassociation=kobserved/[I][m−1s−1] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Chymotrypsin-like activity | PGPH activity | Trypsin-like activity | |

| TMC-95A (1) | 720000 ± 75000 | 71000 ± 23000 | N/A[b] |

| (4 – 8 nm) | (50 – 200 nm) | ||

| TMC-95B (2) | 540000 ± 80000 | 44000 ± 12000 | N/A |

| (6 – 10 nm) | (100 – 250 nm) | ||

| 14 | 190000 ± 50000 | 15000 ± 2000 | N/A |

| (30 – 50 nm) | (100 – 250 nm) | ||

| 16 | 520000 ± 120000 | 96000 ± 12000 | N/A |

| (4 – 10 nm) | (40 – 100 nm) | ||

| 17 | 370000 ± 60000 | 79000 ± 16000 | N/A |

| (4 – 10 nm) | (50 – 150 nm) | ||

| Epoxomicin | 49000 ± 6000 | 110 ± 20 | 370 ± 90 |

| (40 – 100 nm) | (10 – 25 µm) | (1.3 – 10 µm) | |

| Epoxomicin aldehyde | 170000 ± 17000 | 3100 ± 1500 | 1100 ± 150 |

| (10 – 25 nm) | (4 – 10 µm) | (1.3 – 5 µm) | |

The rates of inhibition (kassociation) of both CT-L and PGPH activities were determined for TMC-95A and B and their slow-binding analogues. The rates of inhibition of all three major proteasome catalytic activities were determined for epoxomicin and epoxomicin aldehyde for comparison. A range of concentrations (given in parenthesis) was used to determine the kassociation for inhibition of individual enzymatic activities.

N/A=not applicable.

Table 2.

Concentrations required for inhibition of catalytic activities of the proteasome by synthetic inhibitors.[a]

| Kiapp = [I]/((vo/vs) – 1)[b] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Chymotrypsin-like activity | PGPH activity | Trypsin-like activity | |

| TMC-95A | 1.1 ± 0.1 nm | 29 ± 4 nm | 0.81 ± 0.12 µm |

| TMC-95B | 1.7 ± 0.1 nm | 23 ± 3 nm | 1.1 ± 0.1 µm |

| 12 | 5.7 ± 0.8 nm | 150 ± 20 nm | 9.7 ± 3.5 µm |

| 13 | 6.2 ± 0.4 nm | 130 ± 20 nm | 9.7 ± 2.4 µm |

| 14 | 4.9 ± 0.4 nm | 63 ± 2 nm | 2.6 ± 0.2 µm |

| 15 | 5.3 ± 0.5 nm | 87 ± 12 nm | 5.1 ± 0.5 µm |

| 16 | 1.4 ± 0.1 nm | 11 ± 1 nm | 0.93 ± 0.11 µm |

| 17 | 1.9 ± 0.2 nm | 23 ± 6 nm | 1.2 ± 0.3 µm |

| 18 | 24 ± 2 nm | 110 ± 20 nm | 13 ± 2 µm |

| 19 | 7.0 ± 5.0 µm | 5.3 ± 0.6 µm | 49 ± 34 µm |

| 20 | >100 µm | >100 µm | >100 µm |

| 21 | 22 ± 10 µm | 65 ± 25 µm | >100 µm |

| Epoxomicin aldehyde | 7.0 ± 0.6 nm | 2.6 ± 0.1 µm | 0.35 ± 0.06 µm |

The concentrations required for inhibition of the three major proteasome catalytic activities were determined for TMC-95A and B, their synthetic analogues, and for epoxomicin aldehyde for comparison.

The value vo is the rate of enzyme activity in the absence of inhibitor, and vs is the steady rate of inhibited enzyme activity.

Triols 19 and 21, which lack a substituted amide group at the C-8 position, were found to be much less active than the compounds discussed above. The CT-L inhibitory activity of each compound drops more than 1000-fold from those of the natural products. Tetraol 20 is completely inactive. Triol 19, which contains a benzyl-substituted tyrosine moiety, was found to be three times more active than 21, which has a smaller methyl-protected tyrosine unit.

Discussion

Current SAR studies suggest that some of the structural elements of TMC-95A and B can be modified to simplify the chemical synthesis but yet retain potent biological activity. The asymmetric center on the ketoamide side chain proves to have little effect on proteasome inhibition and can therefore be eliminated to avoid the problematic separation of diastereoisomers. The results obtained from modifications on the cis-enamide side chain, however, are more intriguing. The enamide group can be exchanged with an allylamide with-out affecting all of the proteasome activities. However, when this group was replaced by a more flexible propylamide, a more than tenfold decrease of all three activities was observed. These findings show that the rigid cis-propenyl group can be replaced with a more flexible allyl group without affecting the binding interaction of inhibitors to the proteasome. Reduction of the enamide to a simple alcohol was shown to abolish most of the activities. This result may be explained by the fact that lack of an amide group at that position leads to loss of the favorable hydrogen bond and hydrophobic contacts to the proteasome. Similarly, it has previously been reported that a simple analogue of TMC-95A is 160 times less potent against CT-L activity than TMC-95A, likely as a result of the lack of both the 6,7-dihydroxy groups in the analogue and the exchange of the cis-propenylamide with a propylamide.[33] These results demonstrate the power of chemical synthesis to identify simpler effective proteasome inhibitors derived from natural products. Interestingly, the enamide group appears to be important for slow-binding-inhibitor kinetics.

Given the wide range of cellular processes regulated by the proteasome, controllable and partial blockade of the proteasome functions would be therapeutically beneficial. Reversible and time-limited inhibition of the proteasome can be achieved by using noncovalent inhibitors such as TMC-95s and their synthetic analogues described in this report. Partial inhibition of protein breakdown can be accomplished through rational design of inhibitors that selectively target only one catalytic subunit. All of the proteasome inhibitors currently under clinical investigation are potent inhibitors that act preferentially against CT-L activity. The highly potent TMC-95A and B provide a new lead structure for designing CT-L-activity-selective inhibitors. Numerous studies on proteasomal substrate specificity have been carried out with peptide-based covalent inhibitors.[34–40] These studies highlight the importance of non-P1 interaction in defining and tuning substrate specificity. X-ray crystallography has proven very useful in the determination of the factors dictating the substrate specificity of the proteasome. Crystal structures of the 20S proteasome bound to several different inhibitors have been reported. These inhibitors include peptide aldehyde,[8] lactacystin,[8] epoxomicin,[41] and peptide vinyl sulfones,[42] as well as TMC-95A.[31] Analysis of the TMC-95A structure overlaid with a vinyl sulfone[42] or epoxomicin[31] shows remarkable overlap on both the backbone amides and the P1 and P3 residues. These findings establish the possibility of designing subunit-specific proteasome inhibitors by modification of these two residues of TMC-95A and B. Current investigations clearly indicate that significant changes of potency can be achieved by modification of the P1 cis-propenyl group.

Experimental Section

Synthesis of TMC-95A and B analogues

All analogues were synthesized by procedures modified from those previously reported.[32] The full synthesis will be reported elsewhere. Selected physical data for compound 17: 1H NMR (400 MHz, [D6]acetone): δ = 8.47 (d, 1H, J = 8.31 Hz; NH-12), 8.22 (s, 1H; OH-19), 8.18 (s, 1H; NH-22), 7.72 (brs, 1H; NH-26), 7.58 (d, 1H, J = 9.78 Hz; NH-9), 7.51 (d, 1H, J = 7.43 Hz; H-4), 7.43 (d, 1H, J = 2.01 Hz; H-24), 7.33 (dd, 1H, J = 8.85, 1.02 Hz; H-2), 7.32 (d, 1H, J = 6.20 Hz; NH-33), 7.15 (s, 1H; NH-32), 7.00 (dd, 1H, J = 7.68, 7.59 Hz; H-3), 6.87 (d, 1H, J = 8.16 Hz; H-18), 6.80 (dd, 1H, J = 8.15, 2.16 Hz; H-17), 6.46 (s, 1H; NH-32), 5.85 – 5.75 (m, 1H; H-28), 5.67 (s, 1H; OH-6), 5.25 (s, 1H; OH-7), 5.15 (dq, 1H, J = 17.24, 1.70 Hz; H-29), 4.99 (dq, 1H, J = 10.44, 1.62 Hz; H-29), 4.97 – 4.90 (m, 2H; H-14, H-11), 4.43 (dd, 1H, J = 10.42, 3.07 Hz; H-7), 4.09 (t, J = 10.13 Hz; H-8), 3.81 – 3.77 (m, 2H; H-27), 3.54 (m, 1H, J = 6.95 Hz; H-36), 3.22 (dd, 1H, J = 13.91, 2.35 Hz; H-15), 3.08 (dd, 1H, J = 13.89, 4.85 Hz; H-15), 1.14 (d, 3H, J = 6.98 Hz; CH3), 1.08 (d, 3H, J = 6.96 Hz; CH3) ppm; 13C NMR (125 MHz, [D6]acetone): δ = 202.7, 179.0, 172.5, 172.0, 171.7, 171.5, 160.2, 154.5, 142.0, 135.9, 134.8, 132.4, 131.6, 127.4, 126.7, 124.8, 122.2, 116.8, 115.9, 79.4, 77.8, 55.3, 53.9, 53.7, 51.6, 42.5, 38.6, 38.0, 35.2, 18.4, 18.2 ppm; ESI MS: m/z calcd for C32H36N6NaO10 : 687.3 [M+Na]+; found: 687.2.

Proteasome inhibition assays

Values of kassociation were determined as previously described.[43] Inhibitors were mixed with a fluorogenic peptide substrate and assay buffer (20mm tris(hydroxymethyl) aminomethane (pH 8.0), 0.5mm ethylenediaminetetraacetate, and 0.035% sodium dodecylsulfate (SDS)) in a 96-well plate (SDS was omitted in assays for trypsin-like activity). The chymotrypsin-like, trypsinlike, and PGPH catalytic activities were assayed by using the fluorogenic peptide substrates Suc–Leu–Leu–Val–Tyr–AMC, Boc-–Leu–Leu–Arg–AMC, and Z–Leu–Leu–Glu–AMC (5 µM; AMC = 7-amino-4-methylcoumarin), respectively. Hydrolysis was initiated by the addition of purified bovine erythrocyte 20S proteasome, and the reaction was followed by observation of fluorescence (360 nm excitation/460 nm detection) with a fluorescence plate reader (Wallac Victor fluorescence plate reader, Perkin – Elmer Life Sciences Inc., Boston MA). Reactions were allowed to proceed for 45 min, and data were collected every 10 s. Fluorescence was quantified as arbitrary units and progression curves were plotted for each reaction as a function of time. Values of kassociation ( = kobserved/[I]) were obtained with the Kaleidograph program by using a nonlinear least-squares fit of the data to the Equation (1):

| (1) |

where v0 and vs are the initial and final velocities, respectively, and kobserved is the apparent rate constant for a time-dependent inhibition.[44] The range of inhibitor concentrations tested was chosen so that several half-lives could be observed during the course of the measurement. Values of kassociation were determined from three kinetic runs of at least three inhibitor concentrations.

Values of Kiapp were determined by using Equation (2):

| (2) |

where vo is the rate of enzyme activity in the absence of inhibitor, and vs is the steady rate of inhibited enzyme activity.[45] In all cases, the substrate concentration was much less than the Michaelis constant. For slow-binding inhibitors, Kiapp values were estimated by taking the average final velocity as vs.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institute of Health (Grant no. CA28824). S.L. gratefully acknowledges the US army breast cancer research program for a postdoctoral fellowship (DAMD-17 – 99 – 1 – 9373). C.M.C. gratefully acknowledges support from the National Institutes of Health (Grant no. GM621 20).

References

- 1.Rock KL, Gramm C, Rothstein L, Clark K, Stein R, Dick L, Hwang D, Goldberg AL. Cell. 1994;78:761–771. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(94)90462-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Craiu A, Gaczynska M, Akopian T, Gramm CF, Fenteany G, Goldberg AL, Rock KL. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:13437–13445. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.20.13437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hershko A, Ciechanover A. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1998;67:425–479. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coux O, Tanaka K, Goldberg AL. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1996;65:801–847. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.65.070196.004101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baumeister W, Walz J, Zuhl F, Seemuller E. Cell. 1998;92:367–380. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80929-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Voges D, Zwickl P, Baumeister W. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1999;68:1015–1068. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.68.1.1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Löwe J, Stock D, Jap B, Zwickl P, Baumeister W, Huber R. Science. 1995;268:533–539. doi: 10.1126/science.7725097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Groll M, Ditzel L, Löwe J, Stock D, Bochtler M, Bartunik HD, Huber R. Nature. 1997;386:463–471. doi: 10.1038/386463a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Unno M, Mizushima T, Morimoto Y, Tomisugi Y, Tanaka K, Yasuoka N, Tsukihara T. Structure. 2002;10:609–618. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(02)00748-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Groll M, Heinemeyer W, Jäich S, Bochtler M, Wolf DH, Huber R. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1999;96:10976–10983. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.20.10976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heinemeyer W, Fischer M, Krimmer T, Stachon U, Wolf DH. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:25200–25209. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.40.25200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bochtler M, Ditzel L, Groll M, Hartmann C, Huber R. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 1999;28:295–317. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.28.1.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ciechanover A. EMBO J. 1998;17:7151–7160. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.24.7151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pamer E, Cresswell P. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 1998;16:323–358. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.16.1.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rock KL, Goldberg AL. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 1999;17:739–779. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.17.1.739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Niedermann G, Geier E, Lucchiari-Hartz M, Hitziger N, Ramsperger A, Eichmann K. Immunol. Rev. 1999;172:29–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1999.tb01354.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kloetzel PM. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2001;2:179–187. doi: 10.1038/35056572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Myung J, Kim KB, Crews CM. Med. Res. Rev. 2001;21:245–273. doi: 10.1002/med.1009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kisselev AF, Goldberg AL. Chem. Biol. 2001;8:739–758. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(01)00056-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goldberg AL, Rock K. Nat. Med. 2002;8:338–340. doi: 10.1038/nm0402-338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Adams J, Behnke M, Chen S, Cruickshank AA, Dick LR, Grenier L, Klunder JM, Ma Y-T, Plamondon L, Stein RL. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 1998;8:333–338. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(98)00029-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bogyo M, McMaster JS, Gaczynska M, Tortorella D, Goldberg AL, Ploegh H. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1997;94:6629–6634. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.13.6629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fenteany G, Standaert RF, Lane WS, Choi S, Corey EJ, Schreiber SL. Science. 1995;268:726–731. doi: 10.1126/science.7732382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Meng L, Mohan R, Kwok BHB, Elofsson M, Sin N, Crews CM. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1999;96:10403–10408. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.18.10403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Adams J. Oncologist. 2002;7:9–16. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.7-1-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Almond JB, Cohen GM. Leukemia. 2002;16:433–443. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shah SA, Potter MW, Gallery MP. Surgery. 2002;131:595–560. doi: 10.1067/msy.2002.121890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Adams J. Trends Mol. Med. 2002;8:S49–S54. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4914(02)02315-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Koguchi Y, Kohno J, Nishio M, Takahashi K, Okuda T, Ohnuki T, Komatsubara S. J. Antibiot. 2000;53:105–109. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.53.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kohno J, Koguchi Y, Nishio M, Nakao K, Kuroda M, Shimizu R, Ohnuki T, Komatsubara S. J. Org. Chem. 2000;65:990–995. doi: 10.1021/jo991375+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Groll M, Koguchi Y, Huber R, Kohno J. J. Mol. Biol. 2001;311:543–548. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lin S, Danishefsky SJ. Angew. Chem. 2002;114:530–533. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.2002, 41, 512 – 515. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kaiser M, Groll M, Renner C, Huber R, Moroder L. Angew. Chem. 2002;114:817–820. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20020301)41:5<780::aid-anie780>3.0.co;2-v. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.2002, 41, 780 – 78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nazif T, Bogyo M. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2001;98:2967–2972. doi: 10.1073/pnas.061028898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Elofsson M, Spittgerber U, Myung J, Mohan R, Crews CM. Chem. Biol. 1999;6:811–822. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(99)80128-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bogyo M, Shin S, McMaster JS, Ploegh HL. Chem. Biol. 1998;5:307–320. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(98)90169-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Loidl G, Groll M, Musiol HJ, Ditzel L, Huber R, Moroder L. Chem. Biol. 1999;6:197–204. doi: 10.1016/S1074-5521(99)80036-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim KB, Myung J, Sin N, Crews CM. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 1999;9:3335–3340. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(99)00612-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Harris JL, Alper PB, Li J, Rechsteiner M, Backes BJ. Chem. Biol. 2001;8:1131–1141. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(01)00080-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Myung J, Kim KB, Lindsten K, Dantuma NP, Crews CM. Mol. Cell. 2001;7:411–422. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00188-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Groll M, Kim KB, Kairies N, Huber R, Crews CM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000;122:1237–1238. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Groll M, Nazif T, Huber R, Bogyo M. Chem. Biol. 2002;9:655–662. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(02)00144-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Meng L, Kwok BHB, Sin N, Crews CM. Cancer Res. 1999;59:2798–2801. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Morrison JF, Walsh CT. Adv. Enzymol. Relat. Areas Mol. Biol. 1988;61:201–301. doi: 10.1002/9780470123072.ch5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McCormack T, Baumeister W, Grenier L, Moomaw C, Plamondon L, Pramanik B, Slaughter C, Soucy F, Stein R, Zühl F, Dick L. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:26103–26109. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.42.26103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]