Abstract

Iron regulatory protein (IRP)-1 and IRP2 inhibit ferritin synthesis by binding to an iron responsive element in the 5' untranslated region of its mRNA. The present study tested the hypothesis that neurons lacking these proteins would be resistant to hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) toxicity. Wild-type cortical cultures treated with 100–300 µM H2O2 sustained widespread neuronal death, as measured by lactate dehydrogenase assay, and a significant increase in malondialdehyde. Both endpoints were reduced by over 85% in IRP2 knockout cultures. IRP1 gene deletion had a weaker and variable effect, with approximately 20% reduction in cell death at 300 µM H2O2. Ferritin expression after H2O2 treatment was increased 1.9-fold and 6.7-fold in IRP1 and IRP2 knockout cultures, respectively, compared with wild-type. These results suggest that iron regulatory proteins, particularly IRP2, increase neuronal vulnerability to oxidative injury. Therapies targeting IRP2 binding to ferritin mRNA may attenuate neuronal loss due to oxidative stress.

Keywords: cell culture, free radical, iron toxicity, neurodegeneration, oxidative stress, stroke

Introduction

Experimental and clinical observations suggest that redox-active iron contributes to neuronal death associated with stroke, CNS trauma, and several neurodegenerative diseases [1–4]. Cells detoxify iron primarily by sequestering it in ferritin, an inducible, 24-mer heteropolymer that has the capacity to store up to 4000 ferric iron atoms in its mineral core [5]. In the CNS, ferritin is increased after ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke [6, 7], traumatic injury [8], and with normal aging [9]. However, evidence to date suggests that after an acute injury this increase is delayed for at least 24 h [6–8]. Furthermore, in the substantia nigra of Parkinsonian patients, minimal or no increase has been observed despite significant iron accumulation [9–11]. These observations are consistent with the hypothesis that inadequate ferritin may contribute to the vulnerability of CNS cells to some oxidative injuries.

Ferritin synthesis is subject to both transcriptional and translational regulation, but the latter predominates in coordinating the cellular response to fluctuating levels of chelatable iron [12]. Ferritin translation is inhibited by two iron-sensing proteins, iron regulatory protein (IRP)-1 and IRP2, which bind to an iron responsive element (IRE) in the 5' untranslated region of both H and L-ferritin mRNA when cell iron levels are low. Although both proteins tend to detach in iron-replete cells, IRP binding analysis suggests that some ferritin mRNA likely remains inhibited even in the presence of high iron levels [13]. Pharmacologic targeting of IRP binding may therefore further increase ferritin expression, decreasing the labile iron pool and consequent oxidative stress.

A selective, high-affinity, nontoxic antagonist of IRP binding to ferritin IRE has not yet been identified. However, the detailed information that is available about the secondary and tertiary structures of the ferritin IRE would facilitate the rational design of such an antagonist if a therapeutic effect seemed likely [14]. In order to investigate the potential of this approach, we have established colonies of IRP1 and IRP2 knockout mice, and have performed a series of experiments to characterize the vulnerability of knockout cells to oxidative injury. In the present study, we tested the hypothesis that IRP1 and IRP2 knockout neurons would be less vulnerable than their wild-type counterparts to the toxicity of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), which is catalyzed by cellular iron [15].

Materials and Methods

Mouse breeding and genotyping

Breeding pairs of IRP1 and IRP2 knockout mice (C57BL6/129 strain [16]) were kindly provided by Rouault and colleagues [21]. All mice used for breeding and culture preparation were the first or second generation offspring of mice heterozygous for the IRP1 or IRP2 knockout gene. In order to minimize variability due to genetic background, results from IRP1 and IRP2 knockout cultures were compared with those from wild-type cultures prepared from descendants of IRP1 or IRP2 heterozygous knockout mice, respectively. Mice were genotyped by PCR, using genomic DNA extracted from tail clippings and the following primers:

IRP1 wild-type: forward: 5'-GAG AGG TCC TCC CTC TTG CT-3'; reverse: 5'-CCA CTC TCT CGA AGG TAG TAG-3'.

IRP2 wild-type forward: 5'-TGT TCC TGT CAG TCC TCG TG-3'; reverse: 5'-GGC CAG ACT GGT CTT CAG AG-3'.

NeoR insert forward: 5'-GAT CTC CTG TCA TCT CAC CT-3'; reverse: 5'-TCA GAA GAA CTC GTC AAG AA-3'. NeoR insert primers were the same for IRP1 and IRP2 knockouts.

Absence of wild-type IRP gene expression in mice identified as homozygous knockouts by this method was confirmed by RT-PCR, using the following primer pairs:

IRP1 forward: 5’-CCC AAA AGA CCT CAG GAC AA-3’; reverse: 5’-CCA CTC TCT CGA AGG TAG TAG-3’.

IRP2: forward: 5'-TCC GAC AGA TCT CAC AGT GG-3'; reverse: 5'-TGA GTT CCG GCT TAG CTC TC-3'.

Cell cultures

Cultures containing both neurons and glial cells were prepared from fetal mice (gestational age 15–17 days), as previously described in detail [17]. Plating medium contained Eagle's minimal essential medium (MEM, Gibco/Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY, USA, Product No.11430), 5% heat inactivated fetal bovine serum (Hyclone, Logan, UT, USA), 5% heat inactivated equine serum (Hyclone), glutamine (2mM), and glucose (23mM). Cultures were incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2. Two-thirds of the culture medium was exchanged twice weekly until 11 days in vitro and daily thereafter. Feeding medium was similar to plating medium, except that it contained 10% equine serum and no fetal bovine serum.

Hydrogen peroxide exposure

Experiments were conducted at 11–16 days in vitro. At this time interval, neurons are easily distinguished from glial cells in this culture system by their phase-bright cell bodies and extensive network of processes. Cultures were washed free of serum and placed into MEM containing 10mM glucose (MEM10). H2O2 was diluted from a 3% stock solution immediately prior to its addition to cultures, which were then rapidly returned to the incubator for 24 h.

Assessment of Injury

Cell death was quantified by assaying the activity of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) released into the culture medium, which is an accurate marker of both necrotic and apoptotic death in these cultures [18, 19]. Details of this method have previously been published [17,18]. Since culture LDH activity varies somewhat with its density and age, LDH values were normalized to the mean value in sister cultures treated concomitantly with 300 µM NMDA (=100), which releases essentially all neuronal LDH without injuring astrocytes [18]. The mean LDH activity in sister cultures subjected to medium exchange (sham wash) only was subtracted from all values to quantify the signal specific to H2O2 toxicity.

Lipid peroxidation was quantified by malondialdehyde (MDA) assay. Cells were harvested in 5% trichloroacetic acid, sonicated, and centrifuged. The supernatant was collected, and a thiobarbituric acid/acetate solution was added to a final concentration of 0.3% thiobarbituric acid, 7.5% acetic acid (pH 3.5). Samples were heated in a boiling water bath for 15 min, and then were cooled to room temperature. Fluorescence was quantified using excitation wavelength 515 nm, emission wavelength 553 nm, and slit width 5. MDA concentration was extrapolated from fluorescence of control samples containing serial MDA dilutions (Sigma-Aldrich Cat. # T-1642). Protein concentration of a suspension of the pellet was determined by the bicinchoninic acid (BCA) method (Pierce, Rockford, IL); MDA was expressed as nanomoles/mg protein.

Immunoblotting

After washing with 1ml MEM10, cells were lysed in 100 µl buffer containing 210 mM mannitol, 70 mM sucrose, 5 mM HEPES, 1 mM EDTA, 0.1 % sodium dodecyl sulfate, 0.1 % Triton X-100. The lysate was collected, sonicated on ice, and centrifuged. Protein concentration of the supernatant was determined by the BCA method. Samples (30 µg total protein for ferritin and 15 µg for heme oxygenase (HO)-1) were then diluted with 4X loading buffer (Tris-Cl 240 mmol/L, β-mercaptoethanol 20%, sodium dodecyl sulfate 8%, glycerol 40%, and bromophenol blue 0.2%) and heated to 95°C in a water bath for 3–5 minutes. Proteins were separated on 12% SDS-PAGE gels (Ready Gel, Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA), and were then transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) transfer membrane (Immobilon-P, Millipore, Billerica, MA). After washing, nonspecific sites were blocked with 5% nonfat dry milk in a buffer containing 20 mM Tris, 500 mM NaCl, and 0.1% Tween 20 (pH 7.5) for 1 hour at room temperature. Membranes were exposed to the following primary antibodies overnight at 4°C with continuous gentle shaking: 1) rabbit anti-horse spleen ferritin, Sigma-Aldrich, Product No. F5762, 1:250; 2) rabbit anti-HO-1, Assay Designs, Ann Arbor, MI, Product No. SPA-895, 1:5000; 3) rabbit anti-actin (gel loading control), Sigma-Aldrich Product No. A2066. 1:400. Membranes were then washed and treated with secondary antibody (Pierce goat anti-rabbit IgG-HRP, Product # 1858415 1:3000) at room temperature for one hour. Immunoreactive proteins were visualized using Super Signal West Femto Reagent (Pierce, Rockford, IL) and Kodak Gel Logic 2200. Ferritin and HO-1 band densities were normalized to actin band densities from the same sample.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed with one-way analysis of variance. Differences between groups were assessed with the Bonferroni multiple comparisons test.

Results

Genotyping accuracy was confirmed by detecting IRP1 and IRP2 mRNA via RT-PCR. Using wild-type primer pairs with sequences that spanned the neomycin resistance gene insertion site, expected products were observed in wild-type and heterozygous knockout mice, but were absent in homozygous knockouts (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1.

A) RT-PCR using wild-type IRP1 or IRP2 primers, demonstrating lack of gene expression in mice identified by genotyping protocol as knockouts (−/−) and expression in mice identified as homozygous (+/+) or heterozygous (+/−) wild-type. G3PDH: control glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase primers. B) Representative immunoblot from IRP 1 or IRP2 wild-type (WT) or knockout (KO) cultures, 24 h after treatment with 300 µM H2O2 or medium exchange only (sham-wash, SW), stained with antibody to horse spleen ferritin or actin (gel loading control). C) Mean ferritin band density ± S.E.M., scaled to that in IRP1 WT sham-washed cultures (= 1.0). *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001 v. density in corresponding wild-type cultures, n=5/condition, Bonferroni multiple comparisons test.

Ferritin expression is increased in IRP1 and IRP2 knockout cultures

Ferritin was weakly expressed in wild-type cultures at baseline, and did not significantly increase after H2O2 treatment (Fig. 1B, C). Ferritin expression was similar in wild-type cultures prepared from mice descended from either IRP1 or IRP2 heterozygous knockout breeders. In IRP1 knockout cultures, it tended to be greater than in wild-type cultures at baseline and after H2O2 treatment, but the difference reached statistical significance only for the latter (1.9-fold increase). In IRP2 knockouts, ferritin expression was increased fivefold over wild-type at baseline and 6.7-fold after H2O2 treatment.

IRP knockout cultures are less sensitive to hydrogen peroxide

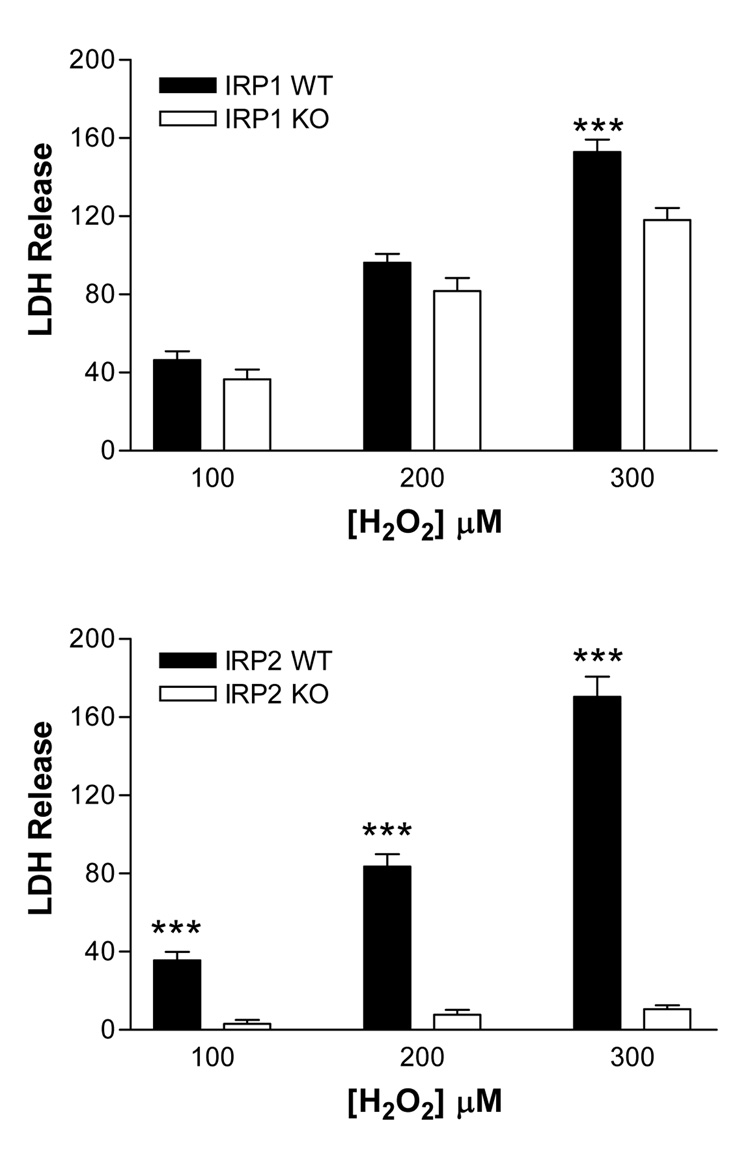

Inspection of wild-type cultures treated with 100–200 µM H2O2 for 24 hours revealed injury mainly to cells with phase-bright cell bodies and extensive processes, which is the typical appearance of neurons in this mixed culture system [20]. Exposure to 200 µM H2O2 was sufficient to increase medium LDH activity to over 80% of that released by killing all neurons with 300 µM NMDA (Fig. 2 A, B). In wild-type cultures treated with 300 µM H2O2, mean LDH values exceeded those in NMDA-treated cultures, consistent with injury that also involved the feeder glial monolayer. In IRP1 knockout cultures, LDH release tended to be less than that in wild-type cultures, but this difference reached statistical significance only at 300 µM H2O2. In IRP2 knockout cultures, LDH release was less than 10% of that in wild-type cultures at all H2O2 concentrations.

Fig. 2.

IRP1 and IRP2 gene knockout reduces cell death after hydrogen peroxide treatment. Cortical cultures were treated with indicated H2O2 concentrations for 24 hours. Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) values in the culture medium were scaled to those in sister cultures treated with 300 µM N-methyl-D-aspartate (=100), which releases virtually all neuronal LDH without injuring glia. The mean LDH values in sister cultures subjected to sham-wash only were subtracted from all values to give the signal specific to H2O2 toxicity. ***P < 0.001 v. corresponding knockout value, 12–27/condition, Bonferroni multiple comparisons test.

Oxidative injury markers are reduced in IRP knockout cultures

Malondialdehyde (MDA) is a sensitive marker of oxidative injury in this cell culture system. In both IRP1 and IRP2 wild-type cultures, MDA was significantly increased by treatment with 100–300 µM H2O2 (Fig. 3), compared with sham-washed controls. In IRP2 knockout cultures, cell malondialdehyde levels after H2O2 treatment were reduced to levels similar to those in sham-washed cultures. A weaker effect was observed in IRP1 knockout cultures that was significantly different from wild-type at all H2O2 concentrations tested.

Fig. 3.

IRP1 and IRP2 gene knockout reduces culture malondialdehyde after hydrogen peroxide treatment. Malondialdehyde (nmol/mg protein) in wild-type and knockout cultures 24 hours after treatment with indicated H2O2 concentrations, or sham wash (SW) only. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 v. value in corresponding wild-type condition.

Heme oxygenase-1 expression is rapidly increased in this culture system by oxidative stress. In wild-type cultures treated with 300 µM H2O2 for 24 hours, HO-1 expression was increased 3–4-fold (Fig. 4). Most of this increase was prevented by IRP2 gene deletion. HO-1 expression in IRP1 knockout cultures was not significantly different from that in wild-type cultures.

Fig. 4.

Heme oxygenase-1 expression after hydrogen peroxide treatment is reduced in IRP2 knockout cultures. Top: Representative immunoblot from IRP 1 or IRP2 wild-type (WT) or knockout (KO) cultures, 24 h after treatment with 300 µM H2O2 or sham-wash (SW), stained with antibody to heme oxygenase-1 or actin (gel loading control). Bottom: Mean band density, scaled to that in IRP1 WT sham-washed cultures (= 1.0). ***P < 0.001 v. density in corresponding wild-type culture, n=5/condition, Bonferroni multiple comparisons test.

Discussion

These results of this study suggest the following: (1) ferritin expression in this cortical cell culture system is negatively regulated by both IRP1 and IRP2; (2) the robust increase in ferritin observed in IRP2 knockout cultures is sufficient to prevent almost all of the cytotoxic effect of H2O2; (3) since IRP1 gene deletion had a weaker effect on both ferritin levels and oxidative injury, IRP2 binding activity is the more promising therapeutic target.

The dominant role of IRP2 in regulating ferritin expression in these cultures is similar to that in vivo. Meyron-Holtz et al [21] reported a marked increase in basal ferritin levels in the forebrain of IRP2 knockout mice, although the effect of oxidant exposure was not tested. However, in contrast to the present results, they noted no alteration whatsoever in brain ferritin in IRP1 knockouts. The significant albeit modest increase in ferritin in these IRP1 knockout cortical cultures may therefore be a cell culture phenomenon only, and may not accurately reflect regulatory mechanisms in the intact CNS.

The iron-dependence of H2O2 toxicity was reported over two decades ago by Starke and Farber [15], who observed that hepatocytes pretreated with the ferric iron chelator deferoxamine were highly resistant to H2O2. Subsequent studies indicated a lysosomal source of this chelatable iron [22], which likely generated oxidative stress by catalyzing hydroxyl radical formation via the Fenton reaction [23]. The iron-dependence of H2O2 toxicity was subsequently confirmed in cultured endothelial cells and astrocytes, using ferritin or deferoxamine to sequester cell iron, respectively [24, 25]. In the present study, the inverse relationship between ferritin expression and cell death suggests a similar iron-dependent mechanism in mixed cortical cultures, which sustain injury primarily to neurons after exposure to 100–200 µM H2O2, and to both neurons and glia at 300 µM.

Altering protein expression by targeting mRNA with small molecules is a novel approach that may be particularly applicable to ferritin, due to its post-transcriptional regulation by IRP-IRE interaction. The feasibility of this concept has been demonstrated in two in vitro systems to date. Tibodeau et al. [26] used a chemical footprinting assay to search for small molecules that interact with the internal loop of the ferritin IRE, a structure unique to ferritin transcripts. This led to identification of the naturally-occurring compound yohimbine as an antagonist of IRP binding. Unfortunately, its affinity for the ferritin IRE appeared to be rather weak, and in a cell-free system it increased ferritin synthesis by only 40%. The aconitase inhibitor oxalomalate was also reported to reduce the binding activities of both IRP1 and IRP2 [27], and to increase ferritin levels in SH-SY5Y and C6 glioma cells 2–3-fold, which was sufficient to protect them from ferric ammonium citrate [28]. Since oxalomalate also inhibits a critical metabolic enzyme, its use for this purpose may be limited by toxicity. Alternatively, cell ferritin levels may be increased by targeting IRP mRNA for degradation using small interfering RNA. In HeLa cells, Wang et al. recently reported that knockdown of both IRP1 and IRP2 increased ferritin and reduced cell death after H2O2 treatment [29]. The utility of IRP knockdown in the intact CNS remains to be established.

The present study demonstrates that both IRP1 and IRP2 gene knockout increases ferritin expression in cortical cell cultures to a level that reduces neuronal vulnerability to H2O2, and in IRP2 knockouts provides near-complete protection. These results are similar to those observed when IRP2 knockout cells are subjected to iron loading by incubation with hemoglobin [30], which suggests that IRP2 binding to ferritin mRNA markedly increases neuronal vulnerability to oxidative stress generated by both endogenous and exogenous iron. Since iron regulatory proteins also regulate the expression of iron transporters, other protective mechanisms besides iron sequestration in ferritin cannot be excluded. It is particularly noteworthy that IRP2 knockouts express less transferrin receptor-1 in CNS cells [21], which may have reduced the lysosomal iron available to catalyze hydroxyl radical formation during H2O2 treatment [22]. However, the inverse relationship between ferritin levels and vulnerability to H2O2 observed in this and other studies [24, 31, 32] suggests that the robust protection provided by IRP2 gene knockout was due at least in part to the 6.7-fold increase in cell ferritin. Further investigation of therapies that target IRP2 binding activity seems warranted.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (NS042273). The authors thank Dr. Tracy Rouault for providing IRP1 and IRP2 knockout breeders.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Ke Y, Ming Qian Z. Iron misregulation in the brain: a primary cause of neurodegenerative disorders. Lancet Neurol. 2003;2:246–253. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(03)00353-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Potts MB, Koh SE, Whetstone WD, Walker BA, Yoneyama T, Claus CP, Manvelyan HM, Noble-Haeusslein LJ. Traumatic injury to the immature brain: inflammation, oxidative injury, and iron-mediated damage as potential therapeutic targets. NeuroRx. 2006;3:143–153. doi: 10.1016/j.nurx.2006.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Millan M, Sobrino T, Castellanos M, Nombela F, Arenillas JF, Riva E, Cristobo I, Garcia MM, Vivancos J, Serena J, Moro MA, Castillo J, Davalos A. Increased body iron stores are associated with poor outcome after thrombolytic treatment in acute stroke. Stroke. 2007;38:90–95. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000251798.25803.e0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stankiewicz J, Panter SS, Neema M, Arora A, Batt CE, Bakshi R. Iron in chronic brain disorders: imaging and neurotherapeutic implications. Neurotherapeutics. 2007;4:371–386. doi: 10.1016/j.nurt.2007.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arosio P, Levi S. Ferritin, iron homeostasis, and oxidative damage. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2002;33:457–463. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(02)00842-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Panahian N, Yoshiura M, Maines MD. Overexpression of heme oxygenase-1 is neuroprotective in a model of permanent middle cerebral artery occlusion in transgenic mice. J. Neurochem. 1999;72:1187–1203. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1999.721187.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wu J, Hua Y, Keep RF, Nakemura T, Hoff JT, Xi G. Iron and iron-handling proteins in the brain after intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. 2003;34:2964–2969. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000103140.52838.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koszyca B, Manavis J, Cornish RJ, Blumbergs PC. Patterns of immunocytochemical staining for ferritin and transferrin in the human spinal cord following traumatic injury. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2002;9:298–301. doi: 10.1054/jocn.2001.0969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Connor JR, Snyder BS, Arosio P, Loeffler DA, LeWitt P. A quantitative analysis of isoferritins in select regions of aged, Parkinsonian, and Alzheimer's diseased brains. J. Neurochem. 1995;65:717–724. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1995.65020717.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Faucheux BA, Martin ME, Beaumont C, Hunot S, Hauw JJ, Agid Y, Hirsch EC. Lack of up-regulation of ferritin is associated with sustained iron regulatory protein-1 binding activity in the substantia nigra of patients with Parkinson's disease. J. Neurochem. 2002;83:320–330. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.01118.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Werner CJ, Heyny-von Haussen R, Mall G, Wolf S. Proteome analysis of human substantia nigra in Parkinson's disease. Proteome Sci. 2008;6:8. doi: 10.1186/1477-5956-6-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Torti FM, Torti SV. Regulation of ferritin genes and protein. Blood. 2002;99:3505–3516. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.10.3505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Theil EC. Targeting mRNA to regulate iron and oxygen metabolism. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2000;59:87–93. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(99)00300-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Theil EC. Integrating iron and oxygen/antioxidant signals via a combinatorial array of DNA - (antioxidant response elements) and mRNA (iron responsive elements) sequences. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2006;100:2074–2078. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2006.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Starke PE, Farber JL. Ferric iron and superoxide ions are required for the killing of cultured hepatocytes by hydrogen peroxide. Evidence for the participation of hydroxyl radicals formed by an iron-catalyzed Haber-Weiss reaction. J. Biol. Chem. 1985;260:10099–10104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.LaVaute T, Smith S, Cooperman S, Iwai K, Land W, Meyron-Holtz E, Drake SK, Miller G, Abu-Asab M, Tsokos M, Switzer R, 3rd, Grinberg A, Love P, Tresser N, Rouault TA. Targeted deletion of the gene encoding iron regulatory protein-2 causes misregulation of iron metabolism and neurodegenerative disease in mice. Nat. Genet. 2001;27:209–214. doi: 10.1038/84859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rogers B, Yakopson V, Teng ZP, Guo Y, Regan RF. Heme oxygenase-2 knockout neurons are less vulnerable to hemoglobin toxicity. Free Rad. Biol. Med. 2003;35:872–881. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(03)00431-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koh JY, Choi DW. Vulnerability of cultured cortical neurons to damage by excitotoxins: Differential susceptibility of neurons containing NADPH-diaphorase. J. Neurosci. 1988;8:2153–2163. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.08-06-02153.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gwag BJ, Lobner D, Koh JY, Wie MB, Choi DW. Blockade of glutamate receptors unmasks neuronal apoptosis after oxygen-glucose deprivation in vitro. Neuroscience. 1995;68:615–619. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(95)00232-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Regan RF, Panter SS. Neurotoxicity of hemoglobin in cortical cell culture. Neurosci. Lett. 1993;153:219–222. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(93)90326-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meyron-Holtz EG, Ghosh MC, Iwai K, LaVaute T, Brazzolotto X, Berger UV, Land W, Ollivierre-Wilson H, Grinberg A, Love P, Rouault TA. Genetic ablations of iron regulatory proteins 1 and 2 reveal why iron regulatory protein 2 dominates iron homeostasis. Embo J. 2004;23:386–395. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Starke PE, Gilbertson JD, Farber JL. Lysosomal origin of the ferric iron required for cell killing by hydrogen peroxide. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1985;133:371–379. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(85)90916-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Halliwell B, Gutteridge JMC. Free Radicals in Biology and Medicine. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Balla G, Jacob HS, Balla J, Rosenberg M, Nath K, Apple F, Eaton JW, Vercellotti GM. Ferritin: A cytoprotective strategem of endothelium. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:18148–18153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liddell JR, Robinson SR, Dringen R. Endogenous glutathione and catalase protect cultured rat astrocytes from the iron-mediated toxicity of hydrogen peroxide. Neurosci. Lett. 2004;364:164–167. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2004.04.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tibodeau JD, Fox PM, Ropp PA, Theil EC, Thorp HH. The up-regulation of ferritin expression using a small-molecule ligand to the native mRNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2006;103:253–257. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509744102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Festa M, Colonna A, Pietropaolo C, Ruffo A. Oxalomalate, a competitive inhibitor of aconitase, modulates the RNA-binding activity of iron-regulatory proteins. Biochem. J. 2000;348(Pt 2):315–320. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Santamaria R, Irace C, Festa M, Maffettone C, Colonna A. Induction of ferritin expression by oxalomalate. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2004;1691:151–159. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2004.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang W, Di X, D'Agostino RB, Jr, Torti SV, Torti FM. Excess capacity of the iron regulatory protein system. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:24650–24659. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703167200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Regan RF, Chen M, Li Z, Zhang X, Benvenisti-Zarom L, Chen-Roetling J. Neurons lacking iron regulatory protein-2 are highly resistant to the toxicity of hemoglobin. Neurobiol. Dis. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2008.04.008. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Garner B, Li W, Roberg K, Brunk UT. On the cytoprotective role of ferritin in macrophages and its ability to enhance lysosomal stability. Free Radic. Res. 1997;27:487–500. doi: 10.3109/10715769709065788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Garner B, Roberg K, Brunk UT. Endogenous ferritin protects cells with iron-laden lysosomes against oxidative stress. Free. Radic. Res. 1998;29:103–114. doi: 10.1080/10715769800300121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]