Abstract

Testosterone acts on cells through intracellular transcription-regulating androgen receptors (ARs). Here, we show that mouse IC-21 macrophages lack the classical AR yet exhibit specific nongenomic responses to testosterone. These manifest themselves as testosterone-induced rapid increase in intracellular free [Ca2+], which is due to release of Ca2+ from intracellular Ca2+ stores. This Ca2+ mobilization is also inducible by plasma membrane-impermeable testosterone-BSA. It is not affected by the AR blockers cyproterone and flutamide, whereas it is completely inhibited by the phospholipase C inhibitor U-73122 and pertussis toxin. Binding sites for testosterone are detectable on the surface of intact IC-21 cells, which become selectively internalized independent on caveolae and clathrin-coated vesicles upon agonist stimulation. Internalization is dependent on temperature, ATP, cytoskeletal elements, phospholipase C, and G-proteins. Collectively, our data provide evidence for the existence of G-protein-coupled, agonist-sequestrable receptors for testosterone in plasma membranes, which initiate a transcription-independent signaling pathway of testosterone.

INTRODUCTION

Steroid hormones act on target cells through their cognate receptors belonging to the intracellular steroid receptor superfamily (reviewed by Evans, 1988; Beato, 1989; Jensen, 1996). These are hormone-regulated transcription factors eliciting either induction or repression of specific genes (reviewed by Kumar and Tindall, 1998). Evidence, however, is accumulating that steroids can also cause nongenomic responses of cells, i.e., responses not mediated through classical nuclear receptors but rather responses initiated at the plasma membrane, presumably through unconventional surface receptors (reviewed by Brann et al., 1995; Wehling, 1997; Grazzini et al., 1998; Nadal et al., 1998; Nemere and Farach-Carson, 1998).

Testosterone, for example, is a steroid hormone that has been described to exert both genomic effects and, recently, also nongenomic effects. Genomic responses of testosterone are mediated through intracellular androgen receptors (ARs), which are 110-kDa proteins with domains for androgen binding, nuclear localization, dimerization, DNA binding, and transactivation (reviewed by Zhou et al., 1994; Quigley et al., 1995). The nongenomic effects are assumed to be mediated through unconventional receptors in plasma membranes. In rat osteoblasts, these membrane receptors have been recently shown to belong to the class of membrane receptors coupled to phospholipase C via a pertussis toxin-sensitive G-protein, which, after binding of testosterone, mediate a rapid increase in intracellular free [Ca2+] ([Ca2+]i) and inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate formation (Lieberherr and Grosse, 1994).

However, unconventional testosterone receptors in plasma membranes can be suspected to be classical intracellular ARs tightly associated with the plasma membrane. This view is not unlikely, because ARs, in contrast to most other steroid receptors, are reported to be localized in the cytoplasm and not in nuclei (Simental et al., 1991; Zhou et al., 1994). Also, rat osteoblasts are known to be typical testosterone target cells containing intracellular AR (Colvard et al., 1989). Here, however, we provide evidence for functional testosterone receptors in plasma membranes of macrophages, which lack classical intracellular AR and which respond to plasma membrane-impermeable testosterone nongenomically with intracellular Ca2+ mobilization.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

IC-21 Cells

The SV40-transformed peritoneal macrophage cell line IC-21 (ATCC no. TIB-186) generated from a C57BL/6 mouse was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). The cells were grown in Iscove’s modified Dulbecco’s medium (IMDM) and l-glutamine (Life Technologies, Eggenstein, Germany) supplemented with 10% FCS, 50 μM β-mercaptoethanol, and 3.024 g of NaHCO3 at 37°C, 5% CO2, and 96% humidity, subcultured once per week, and incubated for 24 h in serum-free medium before use.

RNA Isolation

RNA was isolated from IC-21 cells and testes removed from C57BL/10 mice using the GTC-CsCl method (Sambrook et al., 1989)

Reverse Transcription (RT)-PCR

The PCRs were carried out with the RNA PCR kit from Perkin Elmer (Weiterstadt, Germany). The initial random-primed RT was performed with 1 μg of total RNA in a Minicycler (MJ Research, Biozym, Oldendorf, Germany) and AmpliTaq DNA Polymerase (Perkin Elmer), and four different oligonucleotide primer pairs were used for PCR amplification of the AR. The primer pair AR-P1 (5′-GACCTTGGATGGAGAACTACTCCG-3′) and AR-M1 (5′-GGTTGGTTGTTGTCATGTCCGGC-3′) spanned 511 nucleotides (nt) of the DNA-binding domain of AR. The carboxyl terminus of the AR was probed with three different primer pairs: AR-P2 (5′-ACGTCCTGGAAGCCATTGAGCC-3′) and AR-M2 (5′-CTTGGTGAGCTGGTAGAAGCGC-3′), as well as the sense primers AR-P3 (5′-GAATGTCAGCCTATCTTTCTTAACG-3′) and AR-P4 (5′-TCCTTTGCTGCCTTGTTATCTAGC-3′) together with the antisense primer AR-M3 (5′-TGCCTCATCCTCACACACTGGC-3′). As a control for the integrity of the RNA isolated from IC-21 cells, the low abundant mRNA of the mzfm gene was amplified by RT-PCR using the primer pairs mzfm-P1 (5′-GGCTTAACACCCGAGAGTTCC-3′) and mzfm-M1 (5′-TTATCCTGAGCTGACTGAGGG-3′) as well as mzfm-P2 (5′-GGGTCTATCGCCTGCATCAAGG-3′) and mzfm-M2 (5′-TCCTCACTCTCATGGCTCGG-3′) (Wrehlke et al., 1997, 1999). The AR-P1 and AR-M1 were subjected to 32 cycles at 94°C for 1 min, at 56°C for 1 min, and at 72°C for 1 min. The other primer pairs were used in 32 cycles at 95°C for 1 min, at 60°C for 1 min, and at 72°C for 1 min. PCR fragments were separated in 2% Tris borate-EDTA gels, eluted, and cloned into the pMOSBlue T vector (Amersham, Braunschweig, Germany).

DNA Sequencing

Clones were sequenced with Thermo Sequenase fluorescent-labeled sequencing kit (Amersham) and analyzed with the LICOR sequencer (MWG, Ebersberg, Germany)

Western Blotting

Proteins were separated in 8% SDS polyacrylamide slab gels (Laemmli, 1970) and blotted onto nitrocellulose membranes (0.45 μm pore size; Schleicher & Schuell, Dassel, Germany) with a Biometra (Göttingen, Germany) semidry blot cell. Membranes were incubated with the anti-AR antibody AR (N-20) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Heidelberg, Germany) at a concentration of 0.1 μg/ml diluted in 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 0.15 mM NaCl, and 0.05% Tween (TST) at 23°C for 1 h, washed three times with TST for 10 min, and incubated at 23°C for 1 h with HRP-conjugated goat-anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) diluted 1:50,000 in TST. Antibody detection was performed by the enhanced chemiluminescence plus Western blotting detection system (Amersham).

Determination of [Ca2+]i

IC-21 cells in IMDM were grown on poly-l-lysine-coated glass coverslips until confluence. Then they were washed twice with 20 mM HEPES buffer, pH 7.2, supplemented with 130 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 1 mM CaCl2, 0.5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM Na2HPO4, and 1 mg/ml glucose before they were loaded with 1 μM Fura-2/AM (Amersham, Les Ulis, France) in the same HEPES buffer at room temperature for 30 min. The Ca2+ measurements were performed in a Hitachi (Mountain View, CA) F-2000 spectrofluorometer at 37°C. Reagents were added directly to the cuvette under continuous stirring. Testosterone, testosterone 3-(O-carboxymethyl)oxime-BSA (testosterone-BSA), estradiol, flutamide, and pertussis toxin were from Sigma (St. Quentin, Fallavier, France); 1-dehydrotestosterone was from Steraloids (Wilton, NH). Testosterone-BSA contained <0.1% free testosterone. Cyproterone was kindly provided by Schering (Berlin, Germany); U-73122 [1-(6-((17β-3-metoxyestra-1,3,5(10)-trien-17-yl)-amino)hexyl)-1H-pyrrole-2,5-dione] and U-73343 [1-(6-((17β-3-metoxystra-1,3,5(10)-trien-17-yl)-amino)-hexyl-2,5-pyrrolidine-2,5-dione] were from Biomol Reseach Laboratory (Plymouth, MA). Hormones were dissolved in ethanol. The final concentration of ethanol in the cuvette never exceeded 0.01%, which did not affect [Ca2+]i (cf. Lieberherr and Grosse, 1994). The Fura-2 fluorescence was measured at 340 nm (calcium-bound Fura-2) and 380 nm (free Fura-2) for excitation and 510 nm for emission. The [Ca2+]i was computed from the ratio of 340:380 nm fluorescence values as desribed previously (Grynkiewicz et al., 1985).

Labeling with Testosterone-BSA-FITC

IC-21 cells (5 × 106 cells/ml) in IMDM were allowed to adhere onto poly-l-lysine-coated glass coverslips overnight, washed twice with PBS+ (140 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 6.4 mM Na2HPO4, 1.4 mM KH2PO4, 0.5 mM MgCl2, 0.9 mM CaCl2, pH 7.2), and then incubated at room temperature for 5 s up to 1 h with 100 μl of 1.5 × 10−5 M testosterone-BSA-FITC (Sigma, Deisenhofen, Germany). Only BSA-FITC and BSA were used in the corresponding control experiments. After two washings with PBS+, cells were fixed with 0.5% paraformaldehyde for 30 min. Coverslips were briefly rinsed with PBS+ and mounted on slides in a 1:1 (vol/vol) mixture of glycerol and Vectashield (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) containing 2% (wt/vol) 1,4-diazabicyclo-[2.2.2]octane (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany).

Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy

The specimens were analyzed with a Leica TCS NT confocal laser scanning microscope (CLSM), version 1.5.451 (Leica Lasertechnik, Heidelberg, Germany). FITC fluorescence was excited by a 488-nm argon laser line, and Cy3 and TRITC fluorescence was excited by a 568-nm krypton laser line, respectively. Z-series optical sections were taken at 0.5-μm intervals (Benten et al., 1998, 1999) and evaluated using Adobe Photoshop 5.0 for Windows (Adobe Systems, Mountain View, CA) and CorelDRAW 8 for windows (Corel, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada).

Flow Cytometry

IC-21 cells (107 cells/ml) were suspended in PBS+, and aliquots of 150 μl were centrifuged. The cell pellets were labeled with testosterone-BSA-FITC, BSA-FITC, and the anti-AR antibody AR (N-20) (2 μg/ml) for 5 s up to 1 h as described above. Labeling with rabbit antiserum to sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG) (batch 64.5; a gift from W. Rosner, St. Luke’s-Roosevelt Hospital Center, New York, NY) was performed with dilutions between 1:60,000 and 1:60 for 1 h. Anti-rabbit IgG (whole molecule) FITC conjugate (working dilution, 1:320; Sigma) was used as secondary antibody for 45 min as described previously (Benten et al., 1991). Cells were analyzed in a FACScan (Becton Dickinson, Sunnyvale, CA) with a sample size of 10,000 cells gated on the basis of forward and side scatter. The data were stored and processed using the FACScan software as described previously (Benten et al., 1991).

Internalization of Testosterone-BSA-FITC

Intact IC-21 cells were incubated at room temperature or 37°C for 15 min or 1 h with testosterone-BSA-FITC (1.5 × 10-5 M), BSA-FITC (1.5 × 10-5 M), concanavalin A (Con A)-rhodamine (1:50; Vector), or a rat anti-mouse F4/80 antibody (2 μg/ml; a gift from H. Mossmann, Max-Planck-Institut for Immunobiology, Freiburg, Germany) as first antibody, Biotin-SP-conjugated AffiniPure mouse anti-rat IgG (heavy and light chain; 1:500; Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA) as secondary antibody, and streptavidin-fluorescein (6 μg/107 cells; Amersham). Colocalization was performed with LysoTracker Red DND-99 (10 μM; Molecular Probes, Göttingen, Germany), the anti-clathrin antibody heavy chain (N-19) (2 μg/ml; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and a secondary donkey anti-goat-Cy3 antibody (1:200; a gift from P. Traub, Max-Planck-Institut for Cell Biology, Ladenburg, Germany) or with the anti-caveolin antibody caveolin-1 (N-20) (2 μg/ml; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and as secondary antibody TRITC-conjugated AffiniPure goat anti-rabbit IgG (heavy and light chain; 1:80; Jackson ImmunoResearch). The samples were fixed, embedded, and analyzed by CLSM as described above.

Perturbation of Internalization

Intact IC-21 cells were preincubated at different temperatures or at 37°C with different substances for varying periods before incubation with testosterone-BSA-FITC (1.5 × 10−5 M, if not otherwise stated). The substances were NaN3 (Merck), pertussis toxin (Sigma), U-73122, U-73343, and cytochalasin B and nocodazole (Sigma). The samples were fixed and analyzed by flow cytometry and CLSM as described above.

RESULTS

Absence of Intracellular AR

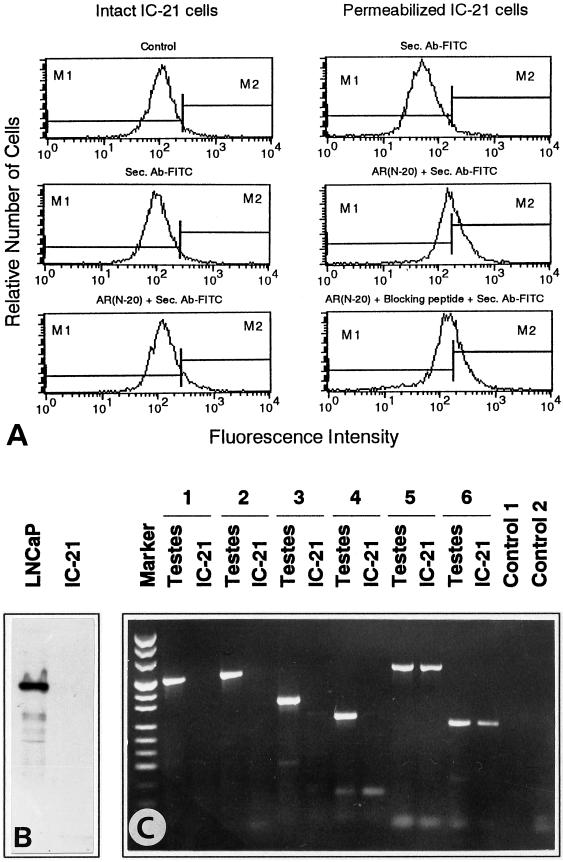

Different techniques were used to examine the presence of classical intracellular AR in mouse macrophages of the cell line IC-21. Both intact cells and permeabilized cells were investigated by flow cytometry using the anti-AR antibody AR (N-20), which is directed against an epitope corresponding to the amino acids 2–21 mapping at the amino terminus of the AR. Incubation of intact IC-21 cells with this antibody did not result in any significant labeling of the cells (Figure 1A). After permeabilization of IC-21 cells, incubation with AR (N-20) resulted in a slight increase in fluorescence intensity. However, this fluorescence was not AR specific, because it could not be competitively displaced by an AR (N-20)-specific blocking peptide (Figure 1A). Also, the anti-AR antibody AR (N-20) did not detect AR in IC-21 cells in Western blots, although this antibody reacted with the AR band at 110 kDa in AR-expressing human prostate cancer LNCaP cells (Figure 1B) (Taplin et al., 1995). Moreover, RT-PCR was used to detect AR mRNA in IC-21 cells and in mouse testes as a control. Using primers spanning the DNA-binding domain and three different regions from the carboxyl terminus of the AR, RT-PCR revealed the expected bands in testes but not in IC-21 macrophages (Figure 1C). DNA sequencing confirmed that the PCR fragments derived from testes RNA contained the predicted regions of the AR. Moreover, the RNA isolated from IC-21 cells was intact, because the low abundant mRNA of the single-copy gene mzfm (Wrehlke et al., 1997, 1999) could be amplified by the same RT-PCR procedure using two different primer pairs (Figure 1C).

Figure 1.

Absence of intracellular AR in IC-21 cells. (A) Flow cytometry of intact and permeabilized IC-21 cells incubated for 1 h with the anti-AR antibody AR (N-20) and secondary fluorescent antibody (Sec. Ab-FITC). In permeabilized cells, the blocking peptide AR (N-20)P cannot competitively displace the slight increase in fluorescence of AR (N-20). (B) IC-21 cells and LNCaP cells as a control were subjected to Western blotting using the anti-AR antibody AR (N-20) and the ECL detection system. Only LNCaP cells reveal the AR band at 110 kDa. (C) RT-PCR with RNA isolated from mouse testes and IC-21 cells with markers (pUC mix, MBI Fermentas) on the left. The primer pair AR-P1/AR-M1 (1) spanned a 511-nt region of the DNA-binding domain of AR. The primer pairs AR-P2/AR-M2 (2), AR-P3/AR-M3 (3), and AR-P4/AR-M3 (4) spanned regions of the carboxyl terminus of the AR with 560, 365, and 281 nt, respectively. The expected bands were only revealed in testes. The primer pairs mzfm-P1/mzfm-M1 (5) and mzfm-P2/mzfm-M2 (6) yielded bands of 640 and 253 nt, respectively, of the low abundant mRNA of the gene mzfm in both testes and IC-21 cells. Control 1, RT-PCR without primers; Control 2, PCR with the primer pair AR-P1/AR-M1 without RNA.

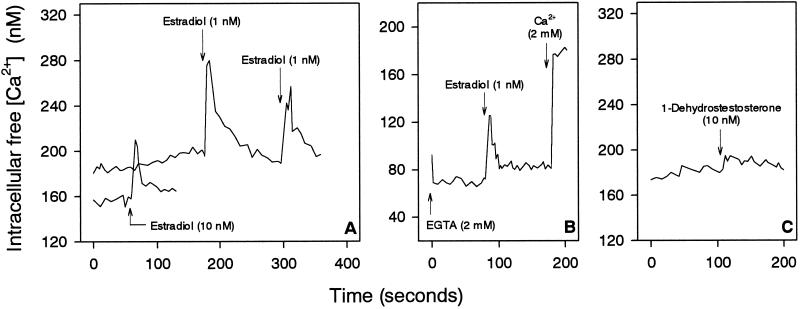

Testosterone-induced Ca2+ Mobilization

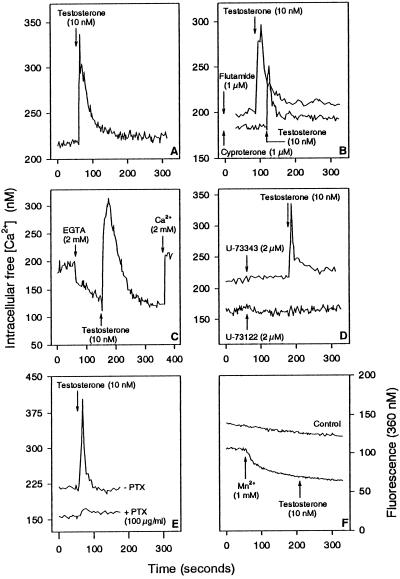

IC-21 cells were loaded with Fura-2 to determine the effect of testosterone on [Ca2+]i. Testosterone at the physiological concentration of 10 nM triggered an immediate spike in [Ca2+]i, which represented a Ca2+ increase by ∼100 nM (Figure 2A). Such a spike was also induced when the cells were preincubated with the AR blockers cyproterone and flutamide in excess (Figure 2B). The Ca2+ increase may be due to influx of extracellular Ca2+ and/or release of Ca2+ from intracellular Ca2+ stores. To test this, extracellular Ca2+ was removed by EGTA before testosterone was added. Testosterone was still able to induce the Ca2+ spike (Figure 2C). However, the testosterone-induced Ca2+ spike was totally abolished by the direct phospholipase C inhibitor U-73122 but not by the inactive control compound U-73343 (Figure 2D). Also, the Ca2+ spike could be inhibited by pertussis toxin (Figure 2E). Mn2+ did not induce any quenching after testosterone treatment (Figure 2F).

Figure 2.

Testosterone-induced Ca2+ mobilization in IC-21 cells. (A) Testosterone causes an immediate Ca2+ spike. (B) Cells were treated with cyproterone for 30 min or flutamide for 60 min before adding testosterone. (C) Cells were incubated with EGTA for 90 s before addition of testosterone. (D) Cells were treated with the phospholipase C inhibitor U-73122 or with the inactive control compound U-73343 for 2 min before adding testosterone. (E) Cells were pretreated with pertussis toxin for 16 h (+ PTX) before addition of testosterone. (F) Cells were incubated with Mn2+ for 2 min before adding testosterone. Arrows indicate addition of substances to IC-21 cells.

However, when testosterone was added for a second or third time shortly after the first addition, it induced a prolonged elevation of [Ca2+]i instead of a Ca2+ spike (Figure 3A). This prolonged elevation in [Ca2+]i was due to both Ca2+ release and Ca2+ import, because after removal of extracellular Ca2+, treatment with testosterone resulted only in a Ca2+ spike instead of a prolonged elevation (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Ca2+ Responses of IC-21 cells to testosterone and testosterone-BSA. (A) A second or third addition of testosterone shortly after the first treatment induces a sustained increase in [Ca2+]i rather than a Ca2+ spike. (B) Cells were treated for 4 min with testosterone and then for 2 min with EGTA before the second addition of testosterone that induced only a Ca2+ spike. (C) The first addition of testosterone-BSA induced a Ca2+ spike, whereas the second addition induced a sustained Ca2+ increase. (D) BSA alone had no effect on [Ca2+]i (lower line). After incubation with testosterone-BSA for 2 min, cells were treated with EGTA before the second addition of testosterone-BSA. (E) After incubation of cells with testosterone-BSA, the cells were pretreated with both EGTA and U-73122 before the second addition of testosterone-BSA. (F) Cells were treated with pertussis toxin for 16 h (+ PTX) before adding testosterone-BSA. Arrows indicate addition of substances to IC-21 cells.

Testosterone coupled to BSA, which is not freely permeable through the cell membrane, had the same effects on [Ca2+]i as free testosterone. It induced first a Ca2+ spike, whereas a second addition caused a prolonged elevation of [Ca2+]i (Figure 3C). The Ca2+ spike was only due to Ca2+ release, whereas the prolonged elevation of [Ca2+]i was due to both Ca2+ release and Ca2+ import (Figure 3, D and E). Moreover, pertussis toxin blocked the testosterone-BSA-induced mobilization of intracellular Ca2+ (Figure 3F).

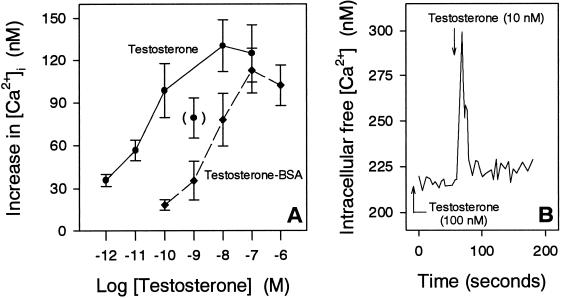

The amount of released Ca2+ induced by the first addition of both testosterone and testosterone-BSA increased with increasing concentrations, reaching apparent saturation at ∼10 nM testosterone and 100 nM testosterone-BSA, respectively (Figure 4A). Moreover, cells responded to a second addition of testosterone again with a Ca2+ spike when the period between first and second additions exceeded at least 10 min (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

Effect of different concentrations of testosterone, testosterone-BSA, and testosterone pretreatment on [Ca2+]i of IC-21 cells. (A) Increase in [Ca2+]i with increasing concentrations of testosterone and testosterone-BSA, respectively. (B) Cells were pretreated with testosterone for 60 min before adding testosterone for a second time.

The rapid nongenomic effects of testosterone on [Ca2+]i of IC-21 cells were specific for testosterone. First, estradiol caused Ca2+ responses differing from those induced by testosterone (Figure 5). Thus, estradiol at a concentration of only 1 nM induced a Ca2+ spike of 100 nM Ca2+, whereas the Ca2+ spike was halved to 50 nM when estradiol was added at 10 nM (Figure 5A). Moreover, a second addition of estradiol resulted in a second Ca2+ spike instead of a prolonged elevation. In addition, the estradiol-induced Ca2+ spikes were due to both Ca2+ release from intracellular stores and Ca2+ influx, because removal of extracellular Ca2+ by EGTA led to a shortened and reduced Ca2+ spike after estradiol treatment (Figure 5B). Second, 1-dehydrotestosterone, the structure of which is very similar to that of testosterone, did not induce any specific Ca2+ response of the cells (Figure 5C).

Figure 5.

Effect of estradiol and 1-dehydrotestosterone on [Ca2+]i of IC-21 cells. (A) Treatment of cells with 1 nM estradiol resulted in a higher increase in [Ca2+]i than 10 nM estradiol. A second addition of estradiol shortly after the first addition again induced a Ca2+ spike. (B) Cells were incubated with EGTA for 1 min before adding estradiol. (C) Addition of 1-dehydrotestosterone had no effect on [Ca2+]i. Arrows indicate the addition of substances to IC-21 cells.

Surface Binding of Testosterone

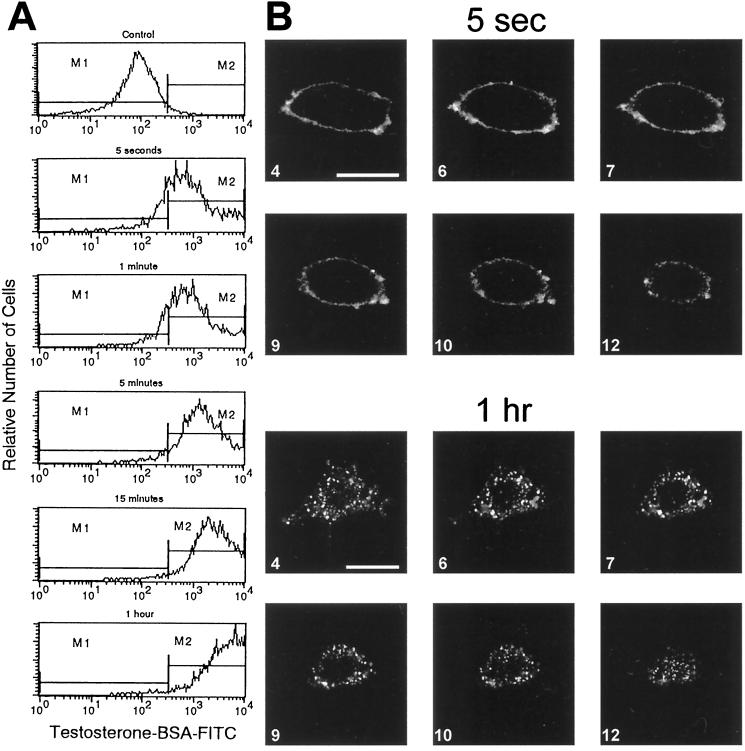

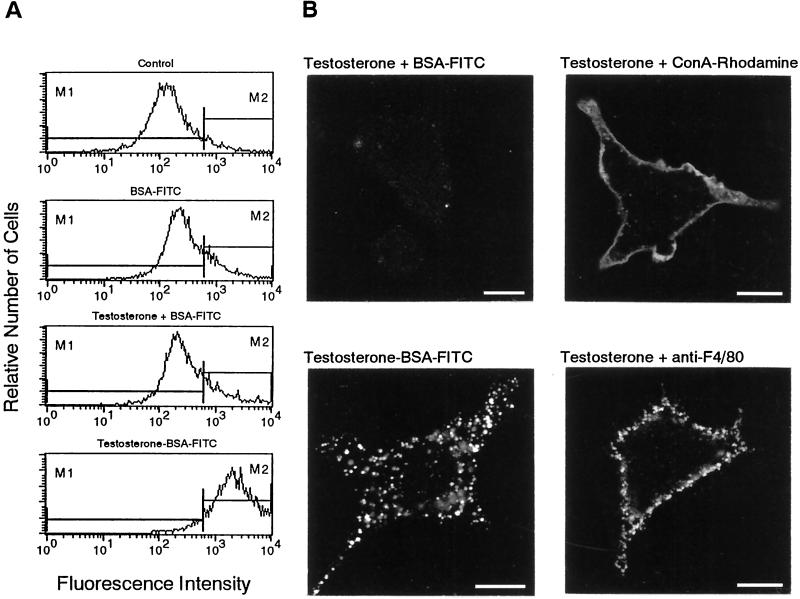

Testosterone binding sites were identified on the surface of intact IC-21 cells. When cells were incubated with the impeded ligand testosterone-BSA coupled to FITC for 5 s, flow cytometry revealed an increase in fluorescence intensity (Figure 6A). Incubation with BSA-FITC alone or together with free testosterone did not result in any significant labeling in comparison with unlabeled control cells (cf. Figure 7A). CLSM detected the fluorescence of the bound testosterone-BSA-FITC exclusively on the surface of IC-21 cells (Figure 6B). The same labeling pattern on the surface showed the plasma membrane marker ConA-rhodamine (cf. Figure 7B). There is some evidence that the SHBG can bind to specific receptors on the plasma membranes, which are able to mediate rapid effects of testosterone and estradiol (Rosner et al., 1998). However, the surface of IC-21 cells had not bound any significant amounts of SHBG, as identified by flow cytometry and CLSM using an anti-SHBG antibody (our unpublished data).

Figure 6.

Surface binding sites of testosterone and their internalization in intact IC-21 cells. (A) Cells were incubated with testosterone-BSA-FITC for various periods between 5 s and 1 h and then analyzed by flow cytometry. (B) CLSM of cells incubated with testosterone-BSA-FITC for 5 s and 1 h. Optical slices of 0.5 μm. Bars, 10 μm.

Figure 7.

Selective internalization of surface binding sites of testosterone. (A) Flow cytometry of IC-21 cells treated with the indicated substances for 15 min. (B) CLSM of cells incubated for 15 min with the indicated substances and the corresponding FITC-labeled secondary antibody. Note the difference between the smooth uniform surface labeling with Con A-rhodamine and the granular surface fluorescence of the F4/80 antigens. Bars, 10 μm.

Selective Internalization of Testosterone Receptors

There is evidence that G-protein-coupled surface receptors can be sequestered (reviewed by Koenig and Edwardson, 1997). To identify such a possible sequestration of surface testosterone receptors, IC-21 cells were incubated with testosterone-BSA-FITC between 5 s and 1 h and analyzed by flow cytometry and CLSM. Flow cytometry revealed an increased labeling with progressive incubation periods (Figure 6A). When incubation lasted for 5 s or 1 min, >80% of the cells were labeled with testosterone-BSA-FITC. After 5 min, however, the percentage of labeled cells was increased to >95%, and the fluorescence intensity of the cells was higher. Thereafter, the number of fluorescent cells remained about the same, whereas the fluorescence intensity of the cells still increased with progressing incubation times, reaching a maximum after ∼1 h. Obviously, cells bound increasing amounts of testosterone-BSA-FITC with progressing incubation times. In parallel with the increase in fluorescence intensity, CLSM revealed an increasing punctate fluorescence inside cells (Figure 6B). Whereas the fluorescence was exclusively localized on the cell surface after 5 s and 1 min, punctate weak fluorescence emerged after 5 min inside cells at their periphery, besides surface fluorescence. After 15 min and 1 h, the punctate fluorescence was increased in intensity and was distributed throughout the whole cytoplasm inside cells.

The internalization of testosterone binding sites was selective. BSA alone or BSA-FITC did not induce any sequestration (Figure 7A). Also, when cells were incubated with free testosterone together with BSA-FITC for 15 min, there was no sequestration, although sequestration was observed when cells were incubated in parallel with testosterone-BSA-FITC (Figure 7, A and B). Moreover, internalization occurred neither with surface-bound ConA-rhodamine nor with the macrophage specific surface marker F4/80 identified by a rat monoclonal antibody against F4/80. Even if the surface labeling of IC-21 cells was performed in the presence of testosterone, there was no internalization of ConA-rhodamine and F4/80 (Figure 7B).

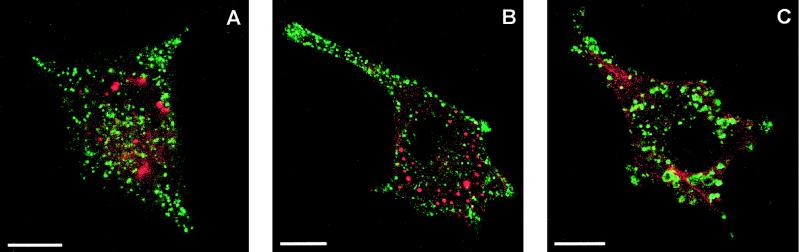

Gross Characteristics of Receptor Internalization

The sequestrated testosterone-BSA-FITC was not contained in acidic vesicles. The latter were identified by CLSM using LysoTracker Red DND-99. The vesicles stained with LysoTracker Red DND-99 did not colocalize with the green punctate fluorescence of testosterone-BSA-FITC (Figure 8A). Also, the sequestrated testosterone binding sites did colocalize neither with clathrin as detected by anti-clathrin antibodies (Figure 8B) nor with caveolin as monitored by anti-caveolin antibodies (Figure 8C).

Figure 8.

CLSM colocalization of the sequestered surface binding sites of testosterone. (A) IC-21 cells were incubated in parallel with testosterone-BSA-FITC and LysoTracker Red DND-99 at 37°C for 1 h. Testosterone-BSA-FITC did not colocalize with acidic vesicles stained with LysoTracker Red DND-99. (B) Testosterone-BSA-FITC was not sequestrated within clathrin-coated vesicles as detected by anti-clathrin antibodies and the Cy3-labeled corresponding secondary antibody. (C) Internalized punctate fluorescence of testosterone-BSA-FITC was not labeled with an anti-caveolin antibody and its corresponding secondary TRITC-conjugated antibody. Bars, 10 μm.

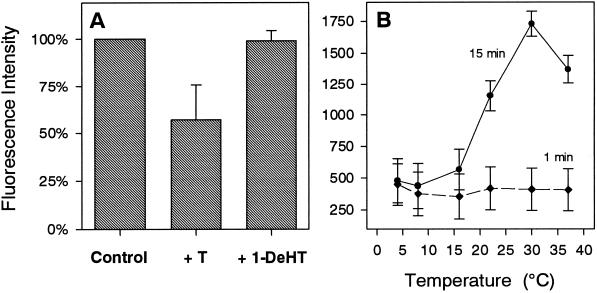

To determine the effect of various parameters on receptor internalization, intact IC-21 cells were incubated with testosterone-BSA-FITC for 15 min, and subsequently fluorescence intensity was analyzed by flow cytometry, and fluorescence localization was analyzed by CLSM. Figure 9A shows that internalization of testosterone-BSA-FITC could be competitively reduced by testosterone but not by the structurally similar compound 1-dehydrotestosterone. Moreover, internalization of surface-bound testosterone-BSA-FITC was largely inhibited at temperatures below ∼16°C, whereas temperature did not affect binding of testosterone-BSA-FITC to the cell surface (Figure 9B). Depletion of ATP by sodium azide resulted in a decrease of fluorescence intensity by ∼40% (Table 1). This fluorescence was localized almost exclusively on the cell surface. Internalization of surface-bound testosterone-BSA-FITC also could be abolished by preincubation with pertussis toxin (Table 1). The phospholipase C inhibitor U-73122 but not the inactive compound U-73343 also blocked internalization, because preincubation with 2 μM U-73122 for 2 min resulted in complete surface localization of testosterone-BSA-FITC, whereas controls have internalized testosterone-BSA-FITC, as revealed by the ∼10% higher fluorescence intensity (Table 1). Finally, internalization obviously involved cytoskeletal elements. Both the tubulin blocker nocodazole and the microfilament blocker cytochalasin B inhibited internalization but not surface binding of testosterone-BSA-FITC (Table 1). Control cells revealed higher fluorescence intensities by ∼25% because of internalization of surface-bound testosterone-BSA-FITC.

Figure 9.

Flow cytometry of the internalization of surface-bound testosterone-BSA-FITC in IC-21 cells. (A) Cells were incubated for 15 min with testosterone-BSA-FITC (10−6 M) in the absence (Control) or in the presence of a 10-fold excess of unlabeled testosterone (+ T) or 1-dehydrotestosterone (+ 1-DeHT). Values normalized to controls are given as means ± SD from five different experiments. (B) Cells were equilibrated for 30 min at the indicated temperatures and then incubated with 1.5 × 10−5 M testosterone-BSA-FITC for 1 or 15 min at the same temperatures. Values represent means ± SD from at least two different experiments.

Table 1.

Effect of various substances on sequestration of surface-bound testosterone-BSA-FITC

| Substance | Fluorescence intensity (%) | Surface-bound fluorescence | Internalized fluorescence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 100 | + | + |

| NaN3 (0.04%, 30 min) | 62.9 ± 6.5 | + | − |

| Pertussis toxin (500 ng/ml, 16 h) | 70.4 ± 0.5 | + | − |

| U-73122 (2 μM, 2 min) | 89.2 ± 5.8 | + | − |

| U-73343 (2 μM, 2 min) | 101.8 ± 5.4 | + | + |

| Nocodazole (2.5 μg/ml, 15 min) | 72.0 ± 5.5 | + | − |

| Cytochalasin B (10 μg/ml, 15 min) | 72.2 ± 5.4 | + | − |

Intact IC-21 cells (1.5 × 106) were incubated with the different substances at the indicated concentrations for the indicated periods before testosterone-BSA-FITC was added for 15 min. Thereafter, cells were fixed, and fluorescence intensity was evaluated by flow cytometry and fluorescence localization by CLSM. Values normalized to controls are given as means ± SD from at least two different experiments.

DISCUSSION

This study provides evidence for the presence of functional receptors for testosterone on the surface of the intracellular AR-free macrophages of the cell line IC-21. Using the impeded ligand testosterone-BSA-FITC, which is not freely permeable to the plasma membrane, CLSM localizes testosterone binding sites on plasma membranes of intact IC-21 cells. These membrane receptors for testosterone cannot be identical with classical intracellular ARs, because ARs are not expressed in IC-21 cells. ARs were detectable by neither flow cytometry nor Western blotting using the anti-AR antibody AR (N-20) directed against the amino terminus of AR or at the mRNA level by RT-PCR using primers probing the DNA-binding domain and three different regions of the carboxyl terminus of the AR. Moreover, the AR blockers cyproterone and flutamide were not able to inhibit binding of testosterone to IC-21 cells. In accordance, previous studies also could not identify intracellular AR in macrophages of the cell line RAW 264.7 (Benten et al., 1999) and in macrophages of different tissues (Gulshan et al., 1990; Frazier-Jessen and Kovacs, 1995; Miller et al., 1996), although the presence of AR was reported in immature monocytic cells (Danel et al., 1985; Cutolo et al., 1993). The reason for this discrepancy is unknown, but the expression of AR in monocytes and macrophages may be developmentally regulated, as it is postulated, for example, to occur in T cells (Kovacs and Olsen, 1987; Viselli et al., 1995; Benten et al., 1999).

The testosterone receptors on the surface of IC-21 cells are functionally coupled to intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis. Indeed, binding of the plasma membrane-impermeable testosterone-BSA induces a rapid increase in [Ca2+]i. This increase, which is also induced by the physiological concentration of 10 nM testosterone, occurs within seconds and is predominantly due to the release of Ca2+ from intracellular Ca2+ stores. However, external Ca2+ also contributes to the increase in [Ca2+]i, which is imported through Ca2+ channels, becoming particularly evident upon a second stimulus with testosterone or testosterone-BSA. Moreover, the specificity of membrane testosterone receptors is further corroborated by our findings 1) that the testosterone-induced Ca2+ release is saturable, 2) that 1-dehydrotestosterone, which is very similar in structure to testosterone, is largely inactive to induce specific Ca2+ release, and 3) that estradiol evokes Ca2+-responses differing from those of testosterone. Moreover, our data reveal that the membrane testosterone receptors not only are functionally coupled with Ca2+ channels in the plasma membrane but also belong to that class of membrane receptors that are coupled to phospholipase C via a pertussis toxin-sensitive G-protein, because Ca2+ release can be blocked by both pertussis toxin and the phospholipase C inhibitor U-73122 but not by the inactive compound U-73343.

The G-protein-coupled receptors for testosterone (GPCRT) in IC-21 cells exhibit a novel peculiarity, i.e., agonist-triggered sequestration. Indeed, this sequestration manifests itself as internalized punctate fluorescence of testosterone-BSA-FITC. The internalization begins a short while 1) after binding of testosterone-BSA-FITC to the surface of IC-21 cells and 2) after Ca2+ mobilization by testosterone. The latter, therefore, may be a precondition for ligand-induced internalization of the GPCRT. This view is also supported by the fact that the phospholipase C inhibitor U-73122 and pertussis toxin inhibit both Ca2+ mobilization and internalization of surface-bound testosterone-BSA-FITC. Our data reveal that the internalization process is not a simple fluid endocytosis or a constitutive endocytotic pathway of IC-21 cells but rather is ligand specific. Thus, internalization of surface-bound testosterone-BSA-FITC is competitively inhibited by testosterone but not by 1-dehydrotestosterone. In addition, GPCRT internalization is selective; i.e., only distinct plasma membrane domains are internalized excluding surface markers such as F4/80 and Con A-rhodamine. GPCRT internalization is consistent with other findings showing that a wide variety of G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs), e.g., the prototypic β2-andrenergic receptor and angiotensin II type 1A receptor, become sequestrated after ligand binding (von Zastrow and Kobilka, 1992; Moore et al., 1995; Koenig and Edwardson, 1997), which is considered important for regulation of signaling, recycling, down-regulation, and responsiveness of the GPCRs (Yu et al., 1993; Pippig et al., 1995; Koenig and Edwardson, 1997).

In general, GPCRs internalize via the clathrin-coated vesicle-mediated endocytotic pathway (Doxsey et al., 1987; Robinson et al., 1996; Zhang et al., 1996), although entry also may be mediated via caveolae (Chun et al., 1994; Kiss and Geuze, 1997). However, our data suggest that GPCRT internalization does not proceed along such pathways. Indeed, the punctate fluorescence of internalized testosterone-BSA-FITC in IC-21 cells is associated with neither clathrin nor caveolin nor acidic vesicles. Obviously, the ligand-triggered entry of GPCRT into IC-21 cells is mediated by a clathrin- and caveolin-independent internalization pathway (cf. Roettger et al., 1995; Robinson et al., 1996). On the other hand, the internalization process of GPCRT in IC-21 cells resembles that observed for numerous other GPRCs insofar as this process is critically dependent on temperature, ATP, and cytoskeletal elements (von Zastrow and Kobilka, 1994; Roettger et al., 1995; Morrison et al., 1996; Koenig and Edwardson, 1997; Koenig et al., 1997).

Testosterone signaling through testosterone surface receptors has also been described in rat osteoblasts (Lieberherr and Grosse, 1994) and murine T cells (Benten et al., 1997, 1999). Howerver, there exist differences in comparison with IC-21 cells. For instance, plasma membranes of rat osteoblasts also possess GPCRT, but these do not become sequestrated upon agonist stimulation and mediate both Ca2+ import of external Ca2+ via voltage-gated Ca2+ channels and Ca2+ release from intracellular Ca2+ stores (Lieberherr and Grosse, 1994). In T cells, the membrane testosterone receptors are not sequestrable, and they mediate only ligand-induced Ca2+ import through non–voltage-gated, Ni2+-blockable Ca2+ channels (Benten et al., 1997, 1999). At present it is too premature to discriminate whether the membrane testosterone receptors in all these different cell types are different or identical but coupled to different signaling pathways dependent on the cell type. In this context, there is also information available that not all cells possess membrane testosterone receptors. For instance, hepatocytes do not respond to testosterone with Ca2+ mobilization, although the cells are able to mobilize Ca2+ in response to progesterone and estradiol (Sanchez-Bueno et al., 1991).

Collectively, our data unequivocally show the presence of functional unconventional GPCRT in plasma membranes of IC-21 cells, which do not mediate the classical genomic AR response but rather initiate novel nongenomic testosterone signaling pathways involving Ca2+ as one of several other possible intracellular mediators. Signal integration into cell functioning and the physiological significance remain to be determined. In particular, it remains elusive whether the testosterone-induced increase in [Ca2+]i per se modulates secondarily expression of specific genes, for example, through Ca2+-responsive promotor elements, negative Ca2+-responsive promotor elements, and/or Ca2+-modulatable transcription factors such as NF-AT, NF-κB, and c-Jun N-terminal kinase (Negulescu et al., 1994; Dolmetsch et al., 1997).

REFERENCES

- Beato M. Gene regulation by steroid hormones. Cell. 1989;56:335–344. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90237-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benten WPM, Bettenhaeuser U, Wunderlich F, Van Vliet E, Mossmann H. Testosterone-induced abrogation of self-healing of Plasmodium chabaudi malaria in B10 mice: mediation by spleen cells. Infect Immun. 1991;59:4486–4490. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.12.4486-4490.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benten WPM, Lieberherr M, Giese G, Wrehlke C, Stamm O, Sekeris CE, Mossmann H, Wunderlich F. Functional testosterone receptors in plasma membranes of T cells. FASEB J. 1999;13:123–133. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.13.1.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benten WPM, Lieberherr M, Giese G, Wunderlich F. Estradiol binding to cell surface raises cytosolic free calcium in T cells. FEBS Lett. 1998;422:349–353. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)00039-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benten WPM, Lieberherr M, Sekeris CE, Wunderlich F. Testosterone induced Ca2+ influx via nongenomic surface receptors in activated T cells. FEBS Lett. 1997;407:211–214. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00346-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brann DW, Hendry LB, Mahesh VB. Emerging diversities in the mechanism of action of steroid hormones. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 1995;52:113–133. doi: 10.1016/0960-0760(94)00160-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chun M, Liyanage UK, Lisanti MP, Lodish HF. Signal transduction of a G protein-coupled receptor in caveolae: colocalization of endothelin and its receptor with caveolin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:11728–11732. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.24.11728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colvard DS, Eriksen EF, Keeting PE, Wilson EM, Lubahn DB, French FS, Rigga BL, Spelsberg TC. Identification of androgen receptors in normal human osteoblast-like cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:854–857. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.3.854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutolo M, Sulli A, Barone A, Seriolo B, Accardo S. Macrophages, synovial tissue and rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 1993;11:331–339. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danel L, Menouni M, Cohen JH, Magaud JP, Lenoir G, Revillard JP, Saez S. Distribution of androgen and estrogen receptors among lymphoid and hemapoietic cell lines. Leuk Res. 1985;9:1373–1378. doi: 10.1016/0145-2126(85)90125-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolmetsch RE, Lewis RS, Goodnow CC, Healy JI. Differential activation of transcription factors induced by Ca2+ response amplitude and duration. Nature. 1997;386:855–858. doi: 10.1038/386855a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doxsey SJ, Brodsky FM, Blank GS, Helenius A. Inhibition of endocytosis by anticlathrin antibodys. Cell. 1987;50:453–463. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90499-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans RM. The steroid and thyroid hormone receptor superfamily. Science. 1988;240:889–895. doi: 10.1126/science.3283939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frazier-Jessen MR, Kovacs EJ. Estrogen modulation of JE/monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 mRNA expression in murine macrophages. J Immunol. 1995;154:1838–1845. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grazzini F, Guillon G, Mouillae B, Zinjg HH. Inhibition of oxytocin receptor function by direct binding of progesterone. Nature. 1998;392:509–512. doi: 10.1038/33176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grynkiewicz G, Poenie MM, Tsien RY. A new generation of Ca2+ indicators with greatly improved fluorescence properties. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:3440–3450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulshan S, McCruden AB, Stimson WH. Oestrogen receptors in macrophages. Scand J Immunol. 1990;31:691–697. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.1990.tb02820.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen EV. Steroid hormones, receptors, and antagonists. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1996;748:1–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1996.tb16223.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiss AL, Geuze HJ. Caveolae can be alternative endocytotic structures in elicited macrophages. Eur J Cell Biol. 1997;73:19–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenig JA, Edwardson JM. Endocytosis and recycling of G protein-coupled receptors. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1997;18:276–287. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(97)01091-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenig JA, Edwardson JM, Humphrey PPA. Somatostatin receptors in Neuro2A neuroblastoma cells: ligand internalization. Br J Pharmacol. 1997;120:52–59. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0700859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs WJ, Olsen NJ. Androgen receptors in human thymocytes. J Immunol. 1987;139:490–493. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar MV, Tindall DJ. Transcriptional regulation of the steroid receptor genes. Prog Nucleic Acids Res Mol Biol. 1998;59:289–306. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6603(08)61035-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laemmli UK. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieberherr M, Grosse B. Androgens increase intracellular calcium concentration and inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate and diacylglycerol formation via a pertussis toxin-sensitive G-protein. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:7217–7223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller L, Alley EW, Murphy WJ, Russell SW, Hunt JS. Progesterone inhibits inducible nitric oxide synthase gene expression and nitric oxide production in murine macrophages. J Leukocyte Biol. 1996;59:442–450. doi: 10.1002/jlb.59.3.442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore RH, Sadovnikoff N, Hoffenberg S, Liu SB, Woodford P, Angelides K, Trial J, Carsrud NDV, Dickey BF, Knoll BJ. Ligand-stimulated β2-adrenergic receptor internalization via the constitutive endocytic pathway into rab5-containing endosomes. J Cell Sci. 1995;108:2983–2991. doi: 10.1242/jcs.108.9.2983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison KJ, Moore RH, Carsrud NDV, Trial J, Millman EE, Tuvim M, Clark RB, Barber R, Dickey BF, Knoll BJ. Repetitive endocytosis and recycling of the β2-adrenergic receptor during agonist-induced steady state redistribution. Mol Pharmacol. 1996;50:692–699. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadal A, Rovira JM, Laribi O, Leon-Quinto T, Andreu E, Ripoll C, Soria B. Rapid insulinotropic effect of 17β-estradiol via a plasma membrane receptor. FASEB J. 1998;12:1341–1348. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.12.13.1341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Negulescu PA, Shastri N, Cahalan MD. Intracellular calcium dependence of gene expression in single T lymphocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:2873–2877. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.7.2873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nemere I, Farach-Carson MC. Breakthroughs and views. Membrane receptors for steroid hormones: a case for specific cell surface binding sites for vitamin D metabolites and estrogens. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;248:443–449. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.8492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pippig S, Andexinger S, Lohse MJ. Sequestration and recycling of β2-adrenergic receptors permit receptor resensitization. Mol Pharmacol. 1995;47:666–676. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quigley CA, De Bellis A, Marschke KB, El-Awady MK, Wilson EM, French FS. Androgen receptor defects: historical, clinical, and molecular perspectives. Endocr Rev. 1995;16:271–321. doi: 10.1210/edrv-16-3-271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson MS, Watts C, Zerial M. Membrane dynamics in endocytosis. Cell. 1996;84:13–21. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80988-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roettger BF, Rentsch RU, Pinon D, Holicky E, Hadac E, Larkin JM, Miller LJ. Dual pathways of internalization of the cholecystokinin receptor. J Cell Biol. 1995;128:1029–1041. doi: 10.1083/jcb.128.6.1029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosner W, Hryb DJ, Khan MS, Nakhla AM, Romas NA. Androgens, estrogens, and second messengers. Steroids. 1998;63:278–281. doi: 10.1016/s0039-128x(98)00017-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Bueno A, Sancho MJ, Cobbold PH. Progesterone and oestradiol increase cytosolic Ca2+ in single rat hepatocytes. Biochem J. 1991;280:273–276. doi: 10.1042/bj2800273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simental JA, Sar M, Lane MV, French FS, Wilson EM. Transcriptional activation and nuclear targeting signals of the human androgen receptor. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:510–518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taplin M-E, Bubley GJ, Shuster TD, Frantz ME, Spooner AE, Ogata GK, Keer HN, Balk SP. Mutation of the androgen-receptor gene in metastatic androgen-independent prostatic cancer. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:1393–1398. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199505253322101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viselli SM, Olsen NJ, Schults K, Steizer G, Kovacs WJ. Immunochemical and flow cytometric analysis of androgen receptor expression in thymocytes. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 1995;109:19–26. doi: 10.1016/0303-7207(95)03479-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Zastrow M, Kobilka BK. Ligand-regulated internalization and recycling of human β2-adrenergic receptors between the plasma membrane and endosomes containing transferrin receptors. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:3530–3538. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Zastrow M, Kobilka BK. Antagonist-dependent and -independent steps in the mechanism of adrenergic receptor internalization. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:18448–18452. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wehling M. Specific, nongenomic actions of steroid hormones. Annu Rev Physiol. 1997;59:365–393. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.59.1.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wrehlke C, Schmitt-Wrede H-P, Qiao Z, Wunderlich F. Enhanced expression in spleen macrophages of the mouse homolog to the human putative tumor suppressor gene ZFM1. DNA Cell Biol. 1997;16:761–767. doi: 10.1089/dna.1997.16.761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wrehlke C, Wiedemeyer W-R, Schmitt-Wrede H-P, Mincheva A, Lichter P, Wunderlich F. Genomic organization of mouse gene zfp 162. DNA Cell Biol. 1999;18:419–428. doi: 10.1089/104454999315303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu SS, Lefkowitz RJ, Hausdorff WP. β-Adrenergic receptor sequestration. A pontential mechanism of receptor resensitization. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:337–341. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Ferguson SSG, Barak LS, Menard L, Caron MC. Dynamin and β-arrestin reveal distinct mechanisms for G protein-coupled receptor internalization. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:18302–18305. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.31.18302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Z-X, Wong C-I, Sar M, Wilson EM. The androgen receptor: an overview. Recent Prog Horm Res. 1994;49:249–274. doi: 10.1016/b978-0-12-571149-4.50017-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]