Public health spans several disciplines dedicated to the improvement of the health and well-being of populations across the globe. This mission broadly focuses on prevention of illness, disease, and injury; utilization of appropriate health-care services; and addressing of health-care disparities. The pursuit of social justice underlies this goal. Core disciplines include epidemiology, environmental health sciences, health policy and management, social and behavioral sciences, and biostatistics. These disciplines draw on a fundamental knowledge of biology, a basic familiarity with social sciences, and an appreciation of socioeconomic and cultural variance among different people.

An undergraduate Public Health Studies (PHS) major gives students a unique opportunity to enter into the world of public health. According to a survey by the Association of Schools of Public Health in 2005,1 13 schools of public health (SPHs) reported that their universities offered undergraduate majors. These schools included Johns Hopkins University (JHU), George Washington University (GWU), Loma Linda University (LLU), University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (UNC-CH), University of California at Berkeley (UC-Berkeley), University of Washington (UW), and Tulane University (TU). Three of these universities—GWU, UW, and TU—as well as four other schools—Boston University (BU), University of California at Los Angeles (UCLA), University of Southern California (USC), and University of South Florida (USF)—offer minors in undergraduate public health. Six of these schools and an additional 13 universities with SPHs offer individual courses for undergraduates. Sixteen schools offer an introductory-level survey course in public health that routinely permits enrollment of students who are not public health majors or minors. Many other schools offer undergraduate training in specific public health-related fields including: health administration, community health education, nutrition, biostatistics, and environmental health. The popularity of these programs is increasing, with most programs established within the last decade. An additional five SPHs list that their universities are currently exploring an undergraduate major in PHS.

There is heterogeneity in these programs, with six SPHs conferring the bachelor's degree: LLU, UNC-CH, USC, GWU, UW, and TU; whereas at another three universities (JHU, UC-Berkeley, and UW), the degree is conferred by the undergraduate campus. Of 17 responding schools, the majority of programs (53%) consider the degree to be a mix of entry-level career and preprofessional, while the other 47% of programs consider their undergraduate degree as primarily preprofessional. In addition, some of the programs are quite small, with fewer than 10 graduates per year, while several others have hundreds of students. The largest programs include two East Coast programs (UNC-CH and JHU) and two California programs (UC-Berkeley and UCLA). At 10 of 11 programs, graduate programs allow students to apply undergraduate credit to the master's degree.

At JHU, the undergraduate major in PHS offers a state-of-the-art, flexible, and challenging curriculum combining undergraduate core courses at the Krieger School of Arts and Sciences (KSAS) with graduate work at the Bloomberg School of Public Health (BSPH). Following is an overview of the program.

DEGREES CONFERRED

The interdepartmental undergraduate PHS major falls within the KSAS and is a four-year bachelor of arts (BA) program based primarily on coursework. The BA program is open to all JHU undergraduate students interested in public health. The PHS major is designed to provide rigorous preparation for advanced study in public health, law, medicine, and related fields. It is appropriate not only for students planning to enter master of health science (MHS)/master of public health (MPH) and doctor of philosophy (PhD) programs, but also for premedical (premed) and prelaw students. In addition, the school offers a five-year BA-MHS program involving additional coursework and a year-long intensive graduate school experience. The BA-MHS programs are interwoven and enable talented undergraduate PHS majors intending to pursue an MPH to develop advising relationships with public health faculty while still undergraduates. Currently, the BA-MHS program is offered through the departments of Environmental Health Sciences and Mental Health. Several other departments are exploring this opportunity and it is expected that the number of available programs will increase in the next two years.

COURSEWORK

PHS majors can choose either a natural science or social science focus. The natural science track requirements mimic all the premed requirements, including physics, chemistry, and advanced biology. The social science track includes introductory courses and upper electives in psychology, sociology, history of medicine, anthropology, economics, political science, geography, and environmental engineering. This track works well for undergraduates interested in health policy, finance, ethics, law, and environmental issues.

All PHS majors take biology, calculus, English, and four public health core requirements in epidemiology, environmental health, health policy and management, and biostatistics. These classes are taught at the undergraduate campus, Homewood, by BSPH faculty. PHS majors take them, along with other requirements for the major, during their first three years at Homewood. As seniors, all PHS majors take at least a semester's worth of graduate courses at BSPH. Many of the other students in these classes have advanced degrees and significant field experience as working public health professionals. Classes at BSPH provide a powerful culmination of the program and an authentic introduction to graduate-level study.

A number of BSPH courses are open to senior undergraduate public health major students, and the faculty have also identified other courses that require preapproval before enrollment by seniors. While students are advised to pursue courses of interest to them, most of the courses chosen are in the BSPH departments of Health Policy and Management, International Health, and Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. In general, the performance of the senior undergraduate students in these graduate-level courses is comparable to the graduate students.

Honors

Students earning either a BA in Public Health in natural science or social science are eligible to receive their degree with honors. In addition to the regular requirements, the BA in Public Health with Honors requires a 3.3 overall grade point average, two semesters of independent research under the mentorship of a faculty member, and participation in a course entitled “Honors in Public Health Seminar.” Students are paired with a faculty member in one of the divisions of the university consistent with their research interests. The student and faculty member come to an agreement on a project that, if involving human subjects, must obtain approval by the Institutional Review Board (IRB). Then, seniors pursue this independent research project concomitant with the “Honors in Public Health Seminar” course.

In this course, students learn pertinent research skills such as how to conduct a literature review, how to navigate the IRB, how to make oral and written presentations, how to identify the ideal study population, and how to develop a research question. During the course, students present their research to the class several times, including a “research in progress” talk, and at the end of the year they present at a university-wide student research forum. Several students have presented at national and international meetings and others have manuscripts under review at major scientific journals. The program has been well-received both by the students and the faculty mentors as a way to introduce students to public health research with a productive outcome for both parties.

DEMOGRAPHICS OF PHS MAJORS

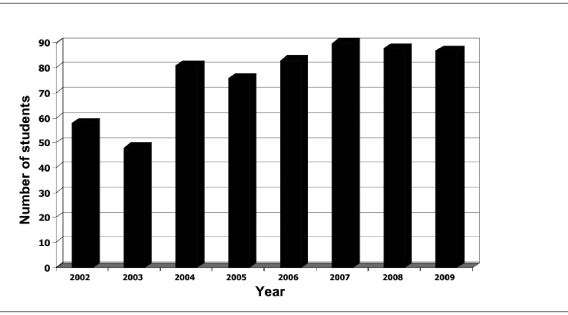

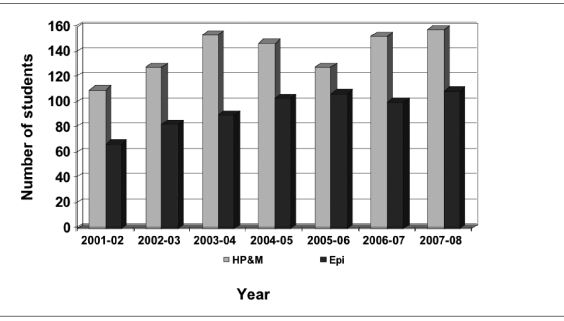

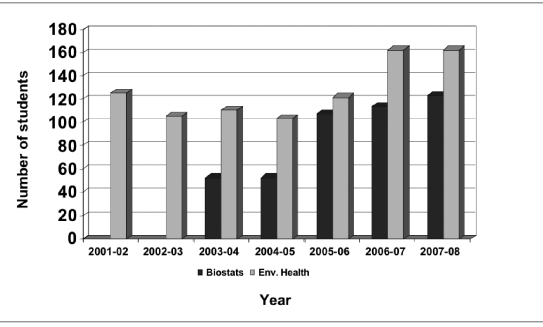

The PHS major's popularity is rising, with a substantial increase in majors between 2002 and 2008 (Figure 1). In addition, an escalating number of undergraduate students are interested in public health issues who are non-PHS majors taking public health courses. Over the past five years, enrollments in Introduction to Health Policy and Management (Figure 2) and Environment and Your Health (Figure 3) have grown beyond the increase in the PHS major. In Environment and Your Health, the majority of non-PHS majors are biology majors, whereas in Introduction to Health Policy and Management, the majority are undecided first- and second-year students.

Figure 1. Number of graduates in the KSAS-BSPH program in undergraduate public health studies across time.

KSAS = Krieger School of Arts and Sciences

BSPH = Bloomberg School of Public Health

Figure 2. Enrollments in Introduction to Health Policy and Management and Introduction to Epidemiology at Johns Hopkins University, 2001–2008.

Figure 3. Enrollments in Introduction to Biostatistics and Environment and Your Health at Johns Hopkins University, 2001–2008.

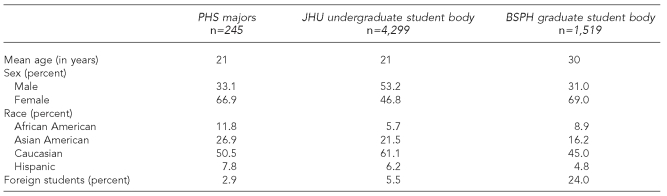

At JHU, students do not declare majors until the end of their first year. However, the number of high school students applying to JHU with the idea of majoring in PHS is on the rise. In 2006, approximately 2% of all applications for admission to KSAS were for the PHS program; however, 13% of those who applied in PHS were accepted for admission and 35% of applicants eventually enrolled at the university. Currently, the program has 314 majors, comprising 89 second-year students, 107 juniors, and 118 seniors. Approximately two-thirds of PHS majors are female, with the majority reporting Caucasian as their race/ethnicity. There are more ethnic minorities and more women PHS majors than in the general undergraduate body. Nearly 75% of PHS majors pursue the natural science track. PHS majors are substantially younger and have less racial diversity than the graduate students at BSPH, where the overall mean age is 30 years, 24% of the student body is international, and the student population is 69% female (Table). At BSPH, U.S. minority students comprise 23% of the total student body and 31% of domestic students.

Table. Demographics of public health students at Johns Hopkins University, by program.

PHS = Public Health Studies

JHU = Johns Hopkins University

BSPH = Bloomberg School of Public Health

OUTCOMES OF UNDERGRADUATES

We have tracked our students' post-graduation plans for the last two years with an interview completed at the time of graduation. Although PHS is often considered a premed track, most of our students pursue graduate school in a variety of other fields, including approximately 30% who attend SPHs immediately after graduation. Of those who went to public health graduate school, 19% pursued an MPH, 48% pursued other masters' degrees, and 4% went on to a PhD program. After graduation, approximately 10% of graduates attended medical school and 11% attended other types of graduate schools, including law schools, schools of nursing, and dental schools.

Nearly one-third of graduates seek employment right after graduation. Of those with jobs at the time of graduation, 38% entered academic jobs, 24% worked at for-profit firms, and 38% worked for nonprofit groups including nongovernmental organizations. Of those who postponed graduate school, the majority planned to attend graduate school within two years.

EXTERNAL ACTIVITIES

JHU students have excelled beyond the classroom on various fronts. We have a number of student athletes and student group leaders in the PHS major. Of note, we have three public health-related groups sponsored by the major: the PHS Forum, Critical Mass, and a group that publishes Epidemic Proportions. Although these groups initially grew out of the PHS major, they have now solicited and received independent funding from the Student Activities Center.

The PHS Forum acts as a voice for the undergraduate public health student body through the organization of information sessions, student panels, and on-campus speakers. It also serves to unite the public health student body through social events, community service, and student networking.

Critical Mass is a student group that unites undergraduate students with an interest in public health through learning, service, and fellowship. The group has developed relationships with other health groups to target large-scale public health efforts such as the Measles Initiative for 2007, and has recently collaborated with Engineers Without Borders to send public health students on trips abroad to assist engineers in conducting health assessments.

Epidemic Proportions is the first undergraduate public health research journal. It has been published annually for the past four years, with two volumes slated for the 2008–2009 academic year. Our student editors have presented their work at the American Public Health Association Meeting and have met with the editors of the American Journal of Public Health to potentially increase undergraduate research publications nationwide. Epidemic Proportions is a valuable medium through which students have had the opportunity to highlight the research endeavors and real-world public health experiences of JHU undergraduates.

Finally, we have partnered with the Baltimore City Health Department and the JHU Department of Pediatrics to establish a Baltimore chapter of Project Health.2 This program works to break the link between poverty and poor health by mobilizing college students to provide sustained public health interventions in partnership with urban medical centers, universities, and community organizations. At JHU, students staff and manage a clinic-based help desk that uses the pediatrician's office as a point of intervention to connect families with critical resources, such as food, housing, and childcare. In the first seven weeks of the 2007–2008 academic year, the clinic was staffed 10 shifts per week with a total of nearly 1,000 volunteer hours helping nearly 100 families. Based on this success, the program is expanding to four other sites including an adolescent clinic, a substance abuse clinic, and a men's clinic in Baltimore.

DISCUSSION

Limitations

Despite the program's benefits, there are inherent limitations to the current setup. First, PHS majors have to take a 30-minute shuttle bus ride between the undergraduate and BSPH campuses during their senior year. While this has been relatively streamlined, with more shuttles available during rush hours and express shuttles between the campuses to limit stops, there are limitations of being able to schedule classes consecutively when having to commute.

In addition, many students complain about a lack of camaraderie and the lack of feeling like a department. We have attempted to address this through a number of social initiatives, including a welcome barbecue for all PHS majors in the fall and a graduation reception for seniors and their families. We have also tried to increase faculty interaction through more formal events, including an orientation for seniors to the BSPH during their first week of classes led by BSPH administrators and faculty, a pizza party for first-year students who newly declare their major as public health, and an afternoon social for rising seniors to get information from graduating seniors regarding how to construct their schedule. In 2008, we organized several public health graduate school information sessions with representation from seven SPHs. Concomitant with BSPH, we organized an entire afternoon forum for graduating seniors to learn about all graduate programs at BSPH, with each department presenting their programs individually.

Unique features

Until recently, undergraduate education in public health has been offered at a relatively small number of universities and colleges. At many other universities that offer an undergraduate degree in public health, it is a terminal program, training students to be entry-level public health employees. Our program is unique in that it gives our students an appreciation of the breadth of public health, but relatively little depth in any one area in public health. Therefore, we view our curriculum as a preprofessional program, where most students go on to pursue additional formal education, albeit in a variety of fields.

In addition, our students benefit from access to students and faculty from around the world at BSPH, with numerous opportunities for research and internships. Taken together, we believe that our program can serve as a model for other undergraduate programs interested in setting up a program to introduce public health to relatively junior students.

Program financing

One of the most complicated, yet fundamentally simple issues of the PHS program is the funding by two different divisions of the university. Each school and its leadership recognizes the program's importance and is invested in its success. Therefore, each is willing to concede on certain financial issues to assure the program's continuity.

Currently, the departments that sponsor BSPH faculty who come to the undergraduate campus to teach one of the core courses are reimbursed through a direct transfer of funds to the BSPH from the KSAS budget. The fees for these courses have a tax to reimburse the BSPH faculty for their time when the students come to the graduate school. In turn, when the senior students attend graduate courses at BSPH, there is no tuition exchange.

CONCLUSIONS

In summary, the JHU PHS program takes advantage of the strengths of two schools within the same university to increase the awareness of undergraduate students to public health issues worldwide. The PHS major represents the best of what JHU has to offer. It draws on a belief in multidisciplinary education, involves cooperation between two schools, and provides our students with a superb education regardless of whether they pursue careers in this field. These students then apply these skills to various end-points including careers in medicine, nursing, public health, and law. It is our hope that through the education of our students on the importance and practice of public health, public understanding will improve and ultimately lead to better health outcomes for our society.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the faculty and administrators of the university, particularly those on the advisory board, who support and teach in the program. The authors specifically thank those who designed and implemented the public health service (PHS) major, Drs. Ellen Mackenzie, Barry Zirkin, Gert Breiger, and James Goodyear; Drs. John Latting and Robin Fox for useful demographic information on applicants and students; and the PHS students and alumni who have provided the enthusiasm and energy to continually assess and improve the program.

Footnotes

Dr. Gebo was supported by the Johns Hopkins University Richard S. Ross Clinician Scientist Award.

REFERENCES

- 1.Associations of Schools of Public Health. Schools of public health survey 2005. [cited 2007 Mar 26]. Available from: URL: http://www.asph.org/document.cfm?page=978.

- 2.Project Health. About us. [cited 2008 Jul 8]. Available from: URL: http://www.projecthealth.org/AboutUs/about.php.