SYNOPSIS

Training adolescents as student researchers is a strategy that can improve the delivery of care at school-based health centers (SBHCs) and significantly shift school health policies impacting students. From 2003 to 2006, the University of California, San Francisco, in partnership with Youth In Focus, implemented a participatory student research project to enhance the existing evaluation of the Alameda County SBHC Coalition and its participating clinic members, and to help develop and implement school health policies. Providing opportunities and training that enabled youth to identify and research the health needs of their peers, as well as advocate for improvements in SBHCs based on their research findings, represents an exciting youth development strategy. This article describes the role the youth played, how their adult partners supported their work, and the impact that their efforts had on the SBHCs and school health programming and policies in the areas of condom accessibility and mental health services.

Community-based participatory research (CBPR) involves all partners equally in the research process and recognizes the strengths, responsibilities, and learning opportunities that each brings to the partnership. Through a collective empowering process, community members, stakeholders, and researchers share responsibility to define problems, collect and interpret data, and implement strategies to address these problems.1

Among its many applications to researching and improving community issues, CBPR has been increasingly recognized as an effective strategy to improve health services.2 By actively involving service recipients in planning and evaluation, the empowering process results in more effective programs.3–5 Use of this approach has increasingly been incorporated into youth-serving programs, especially in underserved communities, and serves many purposes, including enhancing the individual development of youth and encouraging their active involvement in the decisions that affect their lives, as well as contributing to organizational development and capacity building.6 Conversely, the lack of youth engagement in the planning and evaluation of health programs can result in the ineffective allocation of scarce financial and human resources for health promotion.7

There are clearly benefits to partnering with youth to conduct CBPR.8,9 Growing evidence suggests that young people who are civically engaged are less likely to partake in health-damaging behaviors and more likely to have improved health outcomes, including a reduction in rates of alcohol and drug use, and fewer teenage births.10 They also tend to be lifelong civic participants.11,12 Young people benefit when they view themselves as valuable resources and are provided with opportunities for active participation, receive supportive guidance and training, and experience connectivity to adults. Furthermore, participation in evaluation enables youth to play a meaningful role, impacting decisions and developing a greater sense of ownership in the programs that are designed to serve them.7 Investment in youth empowerment and leadership development can inform the creation of effective short- and long-term health-promotion strategies for individuals and communities. Youth can provide compelling firsthand accounts of important issues in their homes, schools, and communities to key stakeholders. Youth also provide ethnically and culturally diverse perspectives that are vital in implementing responsive health programs.13

School-based health centers (SBHCs) and other youth-serving organizations are increasingly involving adolescents in their decision-making through avenues such as youth advisory boards and peer education programs.14,15 CBPR is yet another strategy through which SBHCs can meaningfully involve youth in their program design and improvement efforts. Participatory research and evaluation in the SBHC setting engages clients in the process of identifying the health needs of their peers, defining research questions, creating research instruments, and interpreting their findings to shape the next generation of health interventions.16

This article describes two case studies and lessons learned in the implementation of youth-led CBPR aimed at improving SBHC programs and policies. In the first case study, youth researched the barriers to accessing condoms and other contraceptives in their school and used this information to advocate for a change in the school district condom availability policy. In the second, youth researched the effects of stress on their peers and utilized the data they collected to improve mental health services. Both examples illustrate how the youth were meaningfully involved in decision-making, how adult allies supported their work, and the impact of their efforts.

PROJECT HISTORY AND OVERVIEW

Since 1997, the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) has been conducting a comprehensive evaluation of the Alameda County School-Based Health Center Coalition (SBHC Coalition), a group of middle and high school health centers providing comprehensive health services to students. The evaluation aims to determine how well SBHCs are serving students in Alameda County and to help improve programs to better serve youth. In October 2002, UCSF received a CBPR Grant from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to expand the evaluation by launching a student participatory research project. The premise was to enhance program planning and evaluation efforts by incorporating youth voice, and to provide youth with a meaningful opportunity to gain skills in health research, evaluation, leadership, and public speaking. The Student Research Team (SRT) project allowed the SBHC Coalition and UCSF to actively engage adolescents in the health research and evaluation process. Through a youth development approach, ethnically and economically diverse youth were exposed to professional opportunities in health care, as well as to conducting research and policy advocacy.

The SRT program model and methods

To help implement the SRT project, UCSF partnered with Youth In Focus (YIF), a nonprofit training organization dedicated to youth empowerment through youth-led action research, evaluation, and planning (Youth REP). For nearly 20 years, YIF has guided youth-serving organizations to work in partnership with young people to represent their needs, become effective leaders, and create change in their communities. In 2000, YIF standardized the Youth REP training process into an eight-step curriculum, called Stepping Stones, which includes youth training, adult facilitator coaching, and institutional and community capacity building.17 The curriculum moves youth and adult allies from an awareness of young people as change agents to the CBPR process of building skills in research and evaluation, and culminates with efforts to advocate for and implement programmatic, policy, and community change.18

Between 2003 and 2006, 19 teams of student researchers were recruited from the general school population to conduct research on specific health topics at their schools. In three years of implementation, 101 youth completed this project at one middle school and six high schools with SBHCs. Participants were predominantly female (75%) and in eighth through 11th grades (approximately 90%). Although African American youth were slightly overrepresented in the SRT members (40% of SRT members vs. 25% of the school population), other race/ethnicities were similar to those of the combined school populations, including Asian/Pacific Islander (25% vs. 30% of school population), Caucasian (18% vs. 22%), and Latino (17% vs. 23%).19

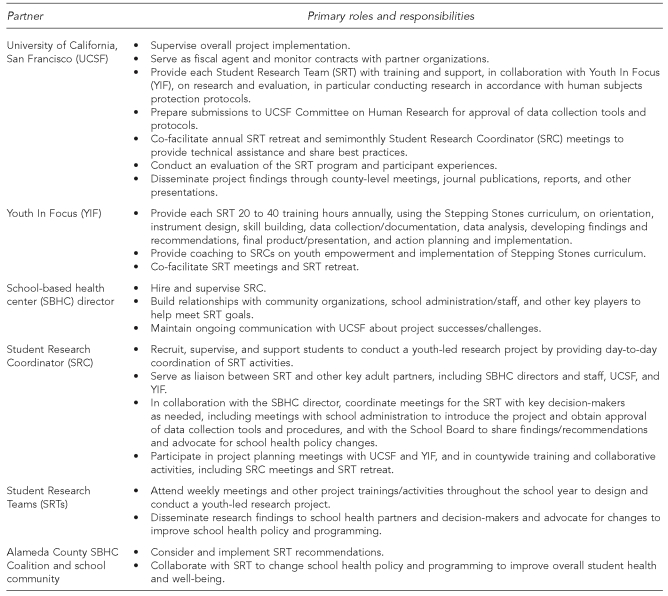

Each SBHC had an SRT comprising two to six students, supervised by a Student Research Coordinator (SRC). The students, many of whom were not otherwise engaged in extracurricular activities, were selected through an application process, and all expressed interest in bettering the health of their peers. Each SRT met approximately once a week after school for one to two hours to discuss pressing health issues and to receive training from UCSF and YIF on implementing youth-led research projects. The Figure outlines the roles and responsibilities of each program partner.

Figure. Student Research Team partner roles and responsibilities.

Throughout the school year, the students implemented each step of their research projects, including topic selection, instrument development, data collection, entry and analyses, and presentation of findings. To select their topics, SRTs brainstormed a list of health issues that most significantly impacted their peers and, through discussion and/or a voting process, decided which topic they would research. Several teams also conducted a brief campus needs assessment to identify the greatest health concerns. The most frequent research topics included depression/suicide, stress, nutrition/body image, and sexual health. Each SRT chose the data collection tool most suitable to conducting research, including anonymous surveys, focus groups, and interviews. UCSF's Committee on Human Research approved all SRT project activities, tools, and research protocols. After data collection, the SRTs were supervised as they prepared the survey data for entry into an online survey database, which automatically calculated frequencies and percentages; interviews and focus groups were transcribed and reviewed for common themes. Adult partners provided detailed feedback for the teams to review and revise their work. SRTs also learned how to summarize their research findings and recommendations in written reports and present their findings to the SBHC staff, school community, and other stakeholders. Youth received a stipend of $250 after each full semester of participation to recognize the significant work they had completed on behalf of their communities.

UCSF researchers provided training to the SRTs on conducting research in compliance with human subjects protection protocols, including protecting confidentiality and obtaining informed consent for voluntary participation from all research participants. Based on these trainings, the youth researchers employed several methods to protect the confidentiality of personal, sensitive information that was obtained through their research, including asking for voluntary participation in surveys that were anonymous and confidential; conducting interviews and focus groups with active parental consent and student assent in private settings; and sharing results in the aggregate.

RESULTS

Case study #1: changing condom distribution policies

History

In one Alameda County school district, two SBHCs serve all high school youth on two central campuses. The first SBHC was opened in 1993 with some hesitation from the neighboring community, particularly concerning the provision of reproductive health services. To ease these concerns, the SBHC was permitted to provide reproductive health services only with parental permission, and the SBHC adopted the District's policy of providing prescriptions for contraceptive supplies, including condoms, that youth were required to fill at a local pharmacy. The second SBHC opened in 1999, replicating the same policies as its predecessor. While students and staff were aware of barriers created by the policy, advocating for change in District policy was perceived to be impossible. It was not until an SRT of six youths decided to research this topic during the 2005–2006 school year that staff felt that it might be the right time to advocate for making it easier for students to obtain condoms on campus.

SRT research and advocacy

In fall 2005, using a sample of convenience, the SRT surveyed 359 students (19% of the school population) to examine why some teens were engaging in unsafe sexual behaviors. The survey was administered in accordance with the California Department of Education Code (51938b),20 which allows surveys measuring student health behaviors, including those related to sex, to be administered with parental notification and the option to withdraw student participation (also known as passive parental consent). The majority of survey respondents reported they were not sexually active. One-quarter (24%, n=86) reported being sexually active and of those students, 36% (n=31) indicated that they did not always use protection. (On the survey, the SRT defined protection as “things that protect you from sexually transmitted diseases and pregnancy, such as condoms, birth control, etc.”) Of those students, 44% (n=14) said they did not always use protection because it was not readily available. The majority (79%, n=24) of sexually experienced students reported that they would be more likely to use condoms if they were available at the SBHC.

As a result of this research, the SRT felt it was important to advocate for increasing students' access to condoms. As a first step in spring 2006, they presented their research to the SBHC Community Advisory Board and the SBHC lead agency's Executive Board, securing their support to present their findings and recommendations to the School Board. During their subsequent presentation to the School Board in fall 2006, the Parent Teacher Association (PTA) president, who was not initially a strong supporter of the youths' recommendations, decided to join their efforts and informed the local PTAs about their work to increase awareness and garner support from parents. After the School Board presentation, members requested the formation of a committee to research the issue and required youth researcher representation. Simultaneously, the SBHC Community Advisory Board, in partnership with the youths, developed a strategy to increase community involvement in this process.

As a result, a community pediatrician, a member of the faith community, the PTA president, and a representative from a local nonpartisan political organization were recruited to voice their support at the School Board meeting in March 2007, when the condom availability policy change would be reviewed for Board vote. In preparation for this meeting, the SRT and the SBHC staff also gathered published research on the impact of schools that distributed condoms on-site, as well as information on how other school districts with similar policies developed their protocols. Due to the advance preparation, transparency of efforts, and community building that occurred prior to the presentation, the youth were met with great support when they presented to the Board.

Outcome and implications

The youths' efforts served as a catalyst to community mobilization and participation, ultimately resulting in revision of the condom policy in March 2007. The new policy allows the SBHCs to dispense condoms on-site, and health educators can dispense condoms following their presentations on campus. Furthermore, education regarding responsible sexual behavior, as well as access to condoms, was made available district-wide through the two SBHCs. Students no longer have to travel to numerous destinations to acquire condoms, thus eliminating a substantial barrier to care. In sum, youth-adult partnerships among students, SBHC staff, parents, and community partners successfully worked to impact district policy and SBHC services.

Case study #2: improving programs to address student stress

History

Alameda County SBHCs offer a variety of counseling services to youth, including individual and group counseling, crisis intervention, and referrals to necessary services. Students are often in need of additional behavioral health interventions, but due to limited funding both in the SBHCs and in the community, there are insufficient resources to serve a large portion of the students. School-wide surveys often reveal that many students are in need of preventive mental health interventions, averting the crisis that would trigger referrals for more expensive care. In a 2003–2004 school-wide survey at all high schools in one Alameda County school district (n=723), approximately 20% (n=137) of students reported that they were nervous or stressed every day or almost every day.21 Thus, the SRT at this school chose to research stress during the 2004–2005 school year because the students felt it was something that affected many students and was a major contributing factor to other health issues.

SRT research and advocacy

To examine their research question, “How does stress affect students and how do they keep it at a safe level?” this SRT conducted surveys with a convenience sample of 260 of their peers (20% of the school population). The research revealed that even though school was a priority for 52% of the students (n=135), schoolwork caused stress for 47% of them (n=122), and 60% (n=156) reported that grades suffered when they were stressed. Most students reported that they did not have time to relax during the school day (63%, n=164) and that they slept less when they were stressed (54%, n=140). Students also reported that, when stressed, they felt irritated (68%, n=177), ignored responsibilities (24%, n=62), treated friends/family badly (18%, n=47), neglected their health (12%, n=31), and/or used drugs/alcohol (4%, n=10). When asked whom they were most likely to talk to when they were stressed, students said their friends (52%, n=135), whereas only 4% (n=10) said they were most likely to go to an SBHC counselor for help.

The SRT presented their findings to the SBHC staff, the SBHC lead agency's Executive Board, and the School Board. The SRT initially recommended greater marketing of SBHC services to increase students' awareness, as well as their comfort levels accessing SBHC counseling services. They developed a student brochure describing the signs of stress, positive coping strategies, and information about the SBHC services. To further increase student access to services and information, the SRT recommended that a peer counseling program be developed to tap into the trust that was known to exist among students and their peers.

Outcome and implications

The SRT's recommendation inspired the creation of the SBHC's Peer Advocate Program to be implemented during the following school year, in which youth serve as advocates and health educators for other students. The overall goals of this program are to give youth: (1) a voice in determining which health-related and social topics should be addressed on campus, (2) a role in designing how they are addressed, and (3) increased comfort with seeking health information by creating a youth-centered forum in which they could seek assistance. This program has a broader reach than addressing solely the issue of stress as originally targeted by the SRT research, largely because of the SRT's original discussions that stress was something that affected and was affected by many other health issues. Thus, the peer counselors will also address topics that relate to stress, such as alcohol and drug abuse.

The Peer Advocate Program has continued for two years since its inception. The youth currently meet weekly to receive training on various health topics and communication skills. Each year, they develop and present two health education presentations for their peers and provide one-on-one health education as needed. Peer advocates receive a stipend of $150 per semester. The program is supported through base funding from the Alameda County SBHC Coalition and the youth stipends are funded through 21st Century Learning grant funds. Since implementation, 26 students have been trained as Peer Advocates in this program and it continues to be part of the SBHC's core services.

DISCUSSION

Participatory research in the SBHC setting was found to be successful in engaging youth, prioritizing major health needs, defining research questions, creating research instruments, and interpreting and applying research findings in ways that were found to be helpful in improving the delivery of SBHC services. Through the Alameda County SRT project, more than 100 students gained research and advocacy skills that led to improved programs and policies for their peers. When asked how the experience had impacted their own lives, participants reported an increase in self-confidence, academic skills, and professional aspirations. Many also indicated that they felt more comfortable with public speaking, research, and leadership skills.

Program challenges

Despite these successes, there were some difficulties initially in implementing the student CBPR model. In mid- and post-project assessments (n=53), students reported challenges in mastering new research skills, specifically designing research questions, selecting topics and questions that students would feel comfortable answering, creating data tools, and conducting data collection, including the logistics of survey administration. Several students were frustrated by the time constraints of their projects, and attendance was poor at times as students juggled multiple responsibilities. Other challenges included group dynamics, such as working with a diverse group, reconciling different attitudes and opinions, and learning to speak up.

Furthermore, despite the two successful case studies reported in this article, other SRTs had mixed experiences with the advocacy phase of their projects. Due to delays and challenges with project implementation, a few of the SRTs ran out of time at the end of the school year and had to end their projects with presentations of their findings to SBHC and school staff, without time to follow through on advocating and implementing their recommendations. Several of the groups that did not have time to advocate for policy or programmatic changes chose to create informational products to address the needs that were identified in their research. For example, a middle school SRT that researched nutrition created an informational brochure for students at their school on the benefits of eating healthy, the negative effects of junk food consumption, and recipes for quick, healthy snacks. Another high school SRT that researched depression and suicide created a pocket-sized “Teen Resource Guide” in an effort to educate their peers and raise awareness on this topic. The guide included a brief checklist for students to assess whether they needed to talk to someone immediately about emotional health concerns, as well as names and numbers of agencies that could be contacted if they were considering suicide or just feeling depressed. These guides were distributed by the health center to all students during the following school year. Efforts such as these often resulted in increased awareness and utilization of the SBHC services.

Lessons learned

The SRCs, UCSF, and YIF staff reported several important lessons in translating student research into successful program and policy change, similar to the experiences of other organizations that have led youth CBPR projects:6,14

Involve all stakeholders: To ensure that the research process was meaningful and productive and that policy and programmatic change could ensue, it was essential that the SRTs partnered with all relevant parties from the onset, including students, school staff and administration, SBHC staff, and the SBHC lead agency's Executive Board.

Ensure that the youth's work is closely tied to the work of the SBHC: Allowing time for youth to present their research to SBHC staff and receive feedback can often be overlooked, given other clinic demands and priorities. Engaging SRT members in staff meetings and allowing them to report regularly to the staff helped to guarantee that the students' efforts were integrated.

Define the decision-making power of each partner: With CBPR, it is imperative to define the types and degrees of decision-making power at each point in the process. Prior to recruiting youth, the adult staff had to consider whether the youth would have complete autonomy in selecting the project topic and, with multiple levels of stakeholders, who would be involved from the beginning in shaping the project's focus. Each SBHC handled this decision slightly differently, with most giving complete decision-making power to the youth, with guided discussions from UCSF and YIF to think through which issues could actually be impacted by the SBHCs, and a few having the SBHC directors and staff review the selected topic for relevance prior to approval and implementation.

Be realistic about the research that can be conducted: Conducting rigorous research is challenging even for the most highly trained adult. While youth gained substantial knowledge regarding the research process, it would be premature to indicate that they had mastered all of the requisite competencies needed to successfully complete research projects. While most SRTs relied on samples of convenience to be able to complete their study tasks in a timely manner, they also learned about the potential biases inherent in not collecting a representative sample. Still, the unique aspect of being able to successfully engage young people in conducting research is a potential building block for future endeavors. Even nonrepresentative samples were powerful enough to build the case to engage concerned adults and present compelling arguments for instituting change.

Provide youth with meaningful venues to share their research: Being given the opportunity to present their research findings to SBHCs and school leadership emboldened the youth and gave them authority and authenticity. Youth felt validated and valued and could see themselves as part of something bigger than their single research focus.

Sustain youth engagement: Community and system-level change can often be a lengthy endeavor, and maintaining youth engagement through this process can be challenging. To keep youth engaged, adult allies supported the youth in creating a clear vision and timeline for the full scope of their projects and provided multiple opportunities for youth to present and get feedback and encouragement on their content and process. Tying stipend payments to significant milestones in the project was another way to help youth recognize the importance of each step of the research process.

Replicating the SRT model

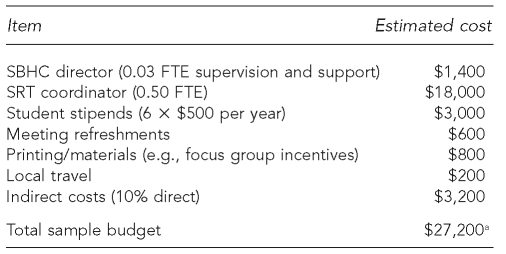

It is important to note that the case studies presented were from a research project that benefited from greater resources than those available to most school systems. The SRT initiative benefited from the CDC grant that funded this countywide, multisite project, which included support from a university evaluation and research team (UCSF) and a training and consulting organization (YIF). However, these projects can be implemented with fewer resources, as long as there is a strong commitment from youth and adult partners to implement the project. The Table outlines a sample budget for a similar youth-led research project, although it is important to note that many of these costs are adjustable. For example, a few of the SBHCs were able to conduct this project with a less than half-time coordinator, and student stipends or project materials can be higher or lower depending on available funds.

Table. Sample project budget to implement the Student Research Team project at one site.

aDoes not include external research and training support from a partnering university or training organization

SBHC = school-based health center

SRT = Student Research Team

FTE = full-time equivalent

For organizations that might be interested in implementing similar projects, additional guidance is available through many youth-serving organizations' websites. YIF's Stepping Stones curriculum is available through its website for a nominal fee (www.youthinfocus.net).

CONCLUSIONS

As described in these case studies, while working with youth requires major adult commitment, youth voice can play a crucial role in advancing policies that are of mutual concern and, at times, can expedite policy and program efforts that have been stymied. SBHCs can clearly benefit from youth perspectives on how to better address health issues in their school communities and make policy and programmatic improvements based on their research and recommendations. Furthermore, the SRT program provided opportunities to engage underrepresented youth in research-related career pathways far earlier in their educational experience, adding in the short term to their sense of self-confidence and achievement. Pursuing strategies that help provide young people with a sense of purpose and connectivity to adults, such as SRTs, represents an exciting practice that could be replicated widely.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the work of all the Alameda County students and their adult allies who participated in the Student Research Team project, along with the Alameda County School Health Services Coalition, which provided additional funding and support for the Coalition Evaluation and Student Research Team efforts. The authors are especially grateful to Adrienne Faxio and Ariana Bennett for their support with the implementation of this project.

Footnotes

This project was made possible by funding from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Grant #R06/CCR921786. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of CDC.

REFERENCES

- 1.Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, Becker AB. Review of community-based research: assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annu Rev Public Health. 1998;19:173–202. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.19.1.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Minkler M, Wallerstein N. Introduction to community-based participatory research. In: Minkler M, Wallerstein N, editors. Community-based participatory research for health. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2002. pp. 3–26. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wallerstein N, Bernstein E. Empowerment education: Freire's ideas adapted to health education. Health Educ Q. 1998;15:379–94. doi: 10.1177/109019818801500402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wallerstein N. Power between evaluator and community: research relationships within New Mexico's healthier communities. Soc Sci Med. 1999;49:39–53. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00073-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wallerstein N. A participatory evaluation model for healthier communities: developing indicators for New Mexico. Public Health Rep. 2000;115:199–204. doi: 10.1093/phr/115.2.199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Horsch K, Little PMD, Smith JC, Goodyear L, Harris E. Youth involvement in evaluation and research. Issues and opportunities in out-of-school time evaluation. Harvard Family Research Project. 2002. Feb, [cited 2008 Jun 13]. Available from: URL: http://www.hfrp.org/publications-resources/browse-our-publications/youth-involvement-in-evaluation-research.

- 7.London J, Zimmerman K, Erbstein N. Youth-led research, evaluation and planning as youth, organizational and community development. In: Sabo Flores K, editor. Youth participatory evaluation: a field in the making: new directions for evaluation. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2003. pp. 33–45. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Flicker S. Who benefits from community-based participatory research? A case study of the Positive Youth Project. Health Educ Behav. 2008;35:70–86. doi: 10.1177/1090198105285927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sabo Flores K. Editor's notes. In: Sabo Flores K, editor. Youth participatory evaluation: a field in the making: new directions for evaluation. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2003. pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Resnick MD, Bearman PS, Blum RW, Bauman KE, Harris KM, Jones J, et al. Protecting adolescents from harm: findings from the National Longitudinal Study on Adolescent Health. JAMA. 1997;278:823–32. doi: 10.1001/jama.278.10.823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Irby M, Ferber T, Pittman K, Tolman J, Yohalem N. Takoma Park (MD): The Forum for Youth Investment, International Youth Foundation; 2001. [cited 2008 Mar 26]. Community – youth development series: youth action: youth contributing to communities, communities supporting youth. Also available from: URL: http://www.cpn.org/topics/youth/cyd/pdfs/Youth_Action.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Syme L. Community participation, empowerment, and health: development of a wellness guide for California. In: Schneider M Jamner, Stokols D., editors. Promoting human wellness: new frontiers for research, practice, and policy. Berkeley (CA): University of California Press; 2001. pp. 78–98. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zeldin S, McDaniel AK, Topitzes D, Calvert M. University of Wisconsin-Madison, Innovation Center for Community and Youth Development, A Division of National 4-H Council. Chevy Chase (MD): National 4-H Council; 2001. [cited 2008 Mar 26]. Youth in decision-making: a study on the impacts of youth on adults and organizations. Also available from: URL: http://www.glsen.org/binary-data/GLSEN_ATTACHMENTS/file/130-1.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Judd B. Washington: The Forum for Youth Investment, Impact Strategies, Inc., and the Alaska Department of Health and Social Services; 2006. [cited 2008 Mar 26]. Incorporating youth development principles into adolescent health programs: a guide for state-level practitioners and policy makers. Also available from: URL: http://www.nnsahc.org/pdfdocs/Yth_Developmt_Ad_Hth.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mandel LA, Qazilbash J. Youth voices as change agents: moving beyond the medical model in school-based health center practice. J Sch Health. 2005;75:239–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2005.00031.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ballonoff Suleiman A, Soleimanpour S, London J. Youth action for health through youth-led research. J Community Practice. 2006;14:125–45. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Youth In Focus. Youth REP step by step: an introduction to youth-led research, evaluation and planning. Oakland (CA): Youth In Focus; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 18.London J, Zimmerman K, Erbstein N. Youth-led research and evaluation: tools for youth, organizational, and community development. Oakland (CA): Youth In Focus; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 19.California Department of Education. Data & statistics. [cited 2008 Mar 26]. Available from: URL: http://www.cde.ca.gov/ds.

- 20.California Law. State of California Education Code. [cited 2008 Mar 26]. Available from: URL: http://www.leginfo.ca.gov/calaw.html.

- 21.California Department of Education. California Healthy Kids Survey. San Francisco: West Ed; 2003. [cited 2008 Jun 13]. Also available from: URL: http://www.wested.org/cs/chks/print/docs/chks_home.html. [Google Scholar]