SYNOPSIS

Objectives

This study explored the current status of the role of state school-based health center (SBHC) initiatives, their evolution over the last two decades, and their expected impact on SBHCs' long-term sustainability.

Methods

A national survey of states was conducted to determine (1) the amount and source of funding dedicated by the state directly for SBHCs, (2) criteria for funding distribution, (3) designation of staff/office to administer the program, (4) provision of technical assistance by the state program office, (5) types of performance data collected by the program office, (6) state perspective on future outlook for long-term sustainability, and (7) Medicaid and the State Children's Health Insurance Program (SCHIP) policies for reimbursement to SBHCs.

Results

Nineteen states reported allocating a total of $55.7 million to 612 SBHCs in school year 2004–2005. The two most common sources of state-directed funding for SBHCs were state general revenue ($27 million) and Title V of the Social Security Act ($7 million). All but one of the 19 states have a program office dedicated to administering and overseeing the grants, and all mandate data reporting by their SBHCs. Sixteen states have established operating standards for SBHCs. Eleven states define SBHCs as a unique provider type for Medicaid; only six do so for SCHIP.

Conclusions

In 20 years, the number of state SBHC initiatives has increased from five to 19. Over time, these initiatives have played a significant role in the expansion of SBHCs by earmarking state and federal public health funding for SBHCS, setting program standards, collecting evaluation data to demonstrate impact, and advocating for long-term sustainable resources.

School-based health centers (SBHCs) represent an important public health strategy for improving the health of the school-age population. Resarch and evaluation have demonstrated SBHCs' ability to get crucial services such as mental health care and screening for high-risk behavior to hard-to-reach populations, especially minorities and males,1,2 reduce adolescents' inappropriate emergency room use,3,4 improve quality of care for chronic conditions5,6 and routine health maintenance, decrease absenteeism and tardiness, and reduce high-risk behaviors.7–10 Cost-benefit studies have attributed the use of SBHCs to a reduction in inpatient, drug, and emergency department expenditures by Medicaid.11

State public health agencies have long played a critical role in the growth of this public health strategy. The first known assessment of state political and policy activities in support of SBHCs was conducted in 1986 by the Center for Population Options (CPO), a national youth advocacy organization (now named Advocates for Youth).12 The study documented the origins of the first state-level SBHC initiatives, including state legislative proposals, budgets, and policy study reports. Its findings revealed emerging interest and significant state-level political and advocacy action in support of (and opposition to) SBHCs at a time when the model was relatively unknown. (There were only 74 known SBHCs at the time of the report.) Authorizing legislation and funding for SBHCs were proposed in eight states (California, Connecticut, Massachusetts, Michigan, New York, Oregon, Virginia, and Wisconsin); only two would pass that year (Massachusetts and New York). Legislative and executive task force reports from 13 states recommended state-level support of SBHCs as remedies to intractable public health concerns such as poor adolescent health outcomes, infant mortality, and teen pregnancy. Further, the 1986 CPO report revealed the earliest pioneers to make state-level investments in SBHCs: New York, whose 1978 funding initiative predated the study, and the inauguration of new state initiatives that year in Connecticut, Massachusetts, Michigan, and Missouri.

By the early 1990s, with noticeable interest from state governments, and increased recognition of the need for sustainable financing, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF) launched “Making the Grade: State and Local Partnerships to Establish School-Based Health Centers,” a $25 million, five-year initiative to stimulate state-level policy. With grants to nine states and an eye toward active dissemination of lessons learned to other states, the RWJF program office established itself as the authority on state SBHC policy. For a decade (1992–2002), Making the Grade sponsored a biennial survey of state public health departments to assess state-sponsored initiatives that advance the SBHC access model. Survey findings, published in peer-reviewed journals and on the program's website, detailed the growing contributions of state initiatives toward sustaining and growing the model and their roles and responsibilities for supporting SBHC planning, start-up, evaluation of outcomes, quality assessment, partnership development, patient revenue recovery, and networking statewide.13–15

For school year 2004–2005, the National Assembly on School-Based Health Care (NASBHC), in partnership with the RWJF school health program office (now called the Center for Health and Health Care in Schools), returned to state public health departments to update the 2002 SBHC finance and policy data and assess state functions, including: grant-making, standard setting, licensure, quality assurance, start-up technical assistance, data collection and evaluation, and networking. The study results are the basis for this article.

METHODS

In May 2005, a survey was mailed to all but one state public health department, as well as the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico. The exception was in the state of Maryland, where the SBHC program was administered by the Governor's Office for Children, Youth, and Families. Survey items included:

The number of SBHCs for the school year 2004–2005,

Amount and source of funding dedicated by the state directly for SBHCs for the corresponding period,

State criteria for funding distribution,

Designation of program office and staff to administer the SBHC program,

Types of technical assistance provided by the state program office,

Types of performance data collected by the program office,

State perspective on future outlook for long-term sustainability, and

Medicaid and SCHIP policies for reimbursement to SBHCs.

The state SBHC policy survey protocol was adapted from the survey previously conducted by the Center for Health and Health Care in Schools. We excluded site-specific information such as hours of operation, staffing, and school type in the revised instrument because these data were being collected simultaneously by NASBHC through a separate survey (the Census) of all known SBHCs for the same time period, school year 2004–2005. Census information constitutes a national database of SBHCs that is maintained by NASBHC.

Activities in place to assure the integrity of the survey process were as follows:

Identifying appropriate individuals to survey: We targeted state agency staff in maternal, child, adolescent, and school health divisions who had the greatest knowledge of SBHCs in their respective state. We asked that Medicaid-related questions be completed by someone with knowledge of reimbursement policies. In most instances, public health insurance reimbursement policies were completed by the Medicaid agency. All surveys were mailed to an identified individual.

Survey administration/efforts to improve the response rate: The questionnaire was mailed to state department of health contacts in May 2005. E-mail reminders were sent in June and August. A second paper copy of the instrument was mailed to all nonresponders in October 2005. State SBHC association directors were updated regularly on the progress of the survey and asked to assist in follow-up requests to the state for the survey to be completed and returned to NASBHC. Between October and December 2005, nonresponders were contacted by phone to encourage their completion of the survey.

Survey content, data cleaning, and data recoding: All paper questionnaires were visually inspected by NASBHC staff prior to data entry. Data were electronically checked for inconsistencies and failure to follow “skip” patterns. If the survey appeared to be incomplete, the individual responsible for completing the survey was notified and attempts were made to collect the data over the phone. Missing data were ascribed where possible based on other information in the survey. For example, in two instances a question regarding the existence of a state-sponsored grant program for SBHCs was not answered and the subsequent question regarding sources of funding for the grant program was answered. In another instance, one state did not provide data for the question characterizing the SCHIP and Medicaid policies in their state, but then responded to a series of questions that identified them as distinctly different. All open-ended responses were recoded to existing categories, where possible. Where responses were known to differ from what was known by NASBHC staff, attempts were made to contact the individual completing the survey and confirm the responses. If the responses were determined to be incorrect and the correct information could not be ascertained, the response was coded as missing data.

Definitions

State-level support included allocation of funding directly to school health centers, having state agency staff dedicated to an SBHC program, promulgating and monitoring program standards, providing technical assistance for school health center operations and evaluation, convening the statewide network, collecting and reporting program data and performance measures, and establishing reimbursement policies for Medicaid and SCHIP.

SBHCs were defined as health centers located on school property and staffed by qualified primary care health-care professionals able to diagnose and treat medical problems in school-age children and adolescents.

RESULTS

We received completed surveys from 49 states and the District of Columbia. Puerto Rico and Tennessee did not complete the survey. The California and Maryland surveys were completed by the state SBHC association because we were unable to get a response from the state's health department (California) and because the executive director of the state SBHC association had been responsible for SBHCs in the Governor's Office for Children, Youth, and Families until just prior to the survey going out (Maryland).

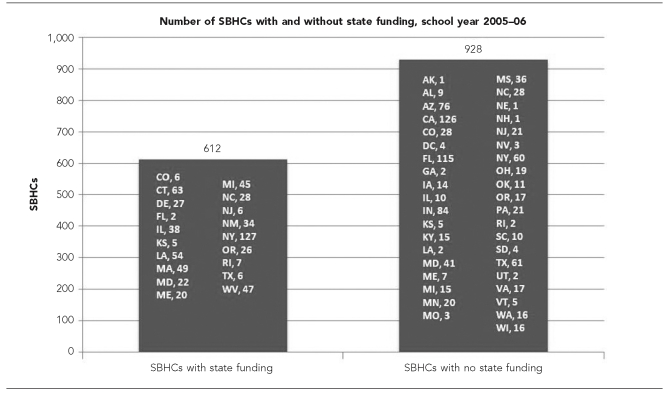

For the purposes of reporting, we divided the state respondents into three groups: states with no SBHCs, states with SBHCs but no funding mechanism, and states with a funding mechanism specifically for SBHCs (Figure 1). Six states reported no SBHCs: Arkansas, Hawaii, Idaho, Montana, North Dakota, and Wyoming. Of the 43 states and the District of Columbia that identified SBHCs in their state, 11 could not provide an exact count (Alabama, Arizona, Indiana, Missouri, Mississippi, Nevada, Ohio, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, South Dakota, and Texas). The number of SBHCs in each state ranged from one (Nebraska, New Hampshire, and Alaska) to 187 (New York). Nineteen states (37%) reported that they provided funding directly to SBHCs. Thirteen of the 19 states provided funding to the majority of SBHCs in their state. Six states (Colorado, Florida, Maryland, North Carolina, New Jersey, and Texas) funded half or fewer.

Figure 1. Distribution of state responses to school-based health center surveya.

NOTE: There were no SBHCs in Arkansas, Hawaii, Idaho, Montana, North Dakota, and Wyoming.

aData from states that could not provide an exact count of SBHCs were obtained from the National Assembly on School-Based Health Care's database of SBHCs.

SBHC = school-based health center

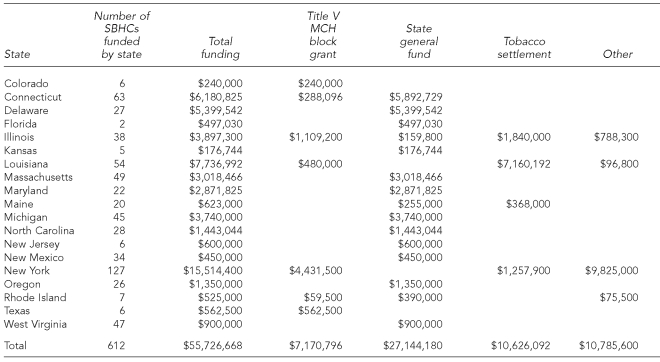

Funding for SBHCs

Nineteen states reported allocating a total of $55.7 million to 612 SBHCs in school year 2004–2005. Table 1 details amounts and sources by state. The range of state grant programs was $176,700 (Kansas) to $15.5 million (New York). The mean grant size was $85,800, with a range of $13,000 in New Mexico to $248,000 for Florida's two state-supported SBHCs.

Table 1. SBHCs and total grant funding directed by state government (2004–2005).

SBHC = school-based health center

MCH = maternal and child health

The two most common sources of state-directed funding for SBHCs (Table 1) were state general revenue (15 states) and Title V of the Social Security Act, the federal-state block grant for maternal and child health programming (seven states). Allocation of state resources was typically directed through a competitive grant program. The criteria most often used by the states to make grant awards included: low-income communities, federally designated medically underserved areas (MUAs), health professional shortage areas (HPSAs), and uninsurance among school-aged youth (data not shown).

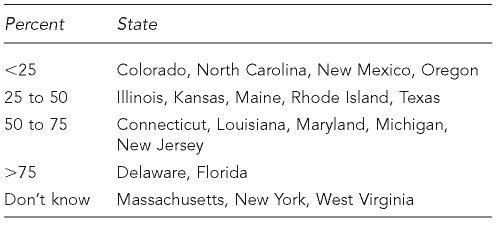

We asked the state program office to estimate the percentage of the SBHCs' operating budget that was covered by state grant funds (Table 2). Seven of the 19 states said they provide 50% or more of the SBHCs' revenue.

Table 2. Percent of SBHC budget covered by state grant funding.

SBHC = school-based health center

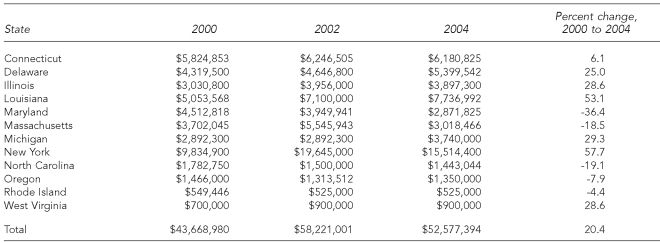

Longitudinal finance data

Because of differences in surveys over time, data could not be examined longitudinally. Nonetheless, comparable data were available from the 12 states that represented the largest and oldest state initiatives (94% of total state allocations) to assess changes in state-directed revenue from the 2000 and 2002 surveys (Table 3). While some state initiatives did experience losses in revenue from 2000 to 2004, on average the collective state allocations increased by 20%. As for the future of these SBHC investments, the outlook appears to be positive, according to the state survey respondents. Of the 19 states, nine envisioned SBHC funding increases on the three-year horizon, while eight predicted stable funding. Only two states (Delaware and Kansas) expected decreases in their investments.

Table 3. State-directed funding for SBHCs, 2000, 2002, and 2004.

SBHC = school-based health center

State policies for technical assistance, data collection, and evaluation

States that did not directly fund SBHCs had limited (if any) policies and practices in other areas such as technical assistance and data collection. The majority of the analysis was restricted to the 19 states that make funding available for SBHCs.

Program office

Of the 19 states that provide grant funding to SBHCs, all but one (Florida) have a program office dedicated to administering and overseeing the grants. Fifteen states reported that the program office was within the state public health agency; five states housed the program jointly or outside of the public health agency. The number of full-time equivalents (FTEs) dedicated to the program office ranged from none to seven, with a mean of 2.6.

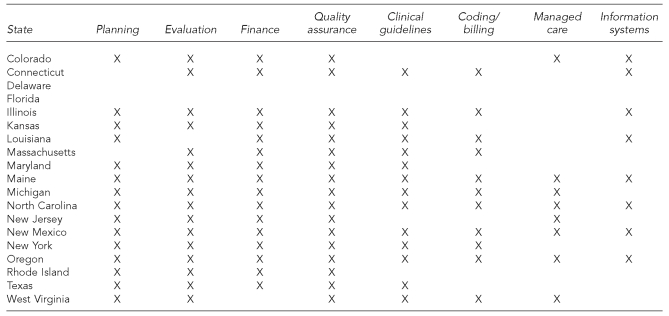

We queried the state program office about categories of technical assistance provided to and the types of data collected from SBHCs. The responses (Figure 2) illustrated active involvement on the part of most state program offices in the development and operations support of SBHCs.

Figure 2. Types of technical assistance available by state.

Data collection

All 19 state program offices mandate data reporting by their SBHC grantees; New York and Oregon require data from nonfunded SBHCs in their states as well. Typical data elements required by the states include operations (staffing, policies, physical space), visits (users, enrollees, diagnoses), and finance (budget, billing). We asked the states to identify specific measures used by the state to assess SBHC performance; all but Illinois and New York collected performance measures. Of the 15 child and adolescent health-care quality measures we listed in the survey, those most commonly used by the state program offices were: physical examination (13 states), risk assessment (10 states), immunizations (eight states), and mental health (eight states). We also asked how the SBHC data were used by the state; the most common responses were for quality improvement (14 states), production of an annual report on the state initiative (14), and advocacy (13).

Setting state standards

Sixteen state program offices have established operating standards for their SBHC grantees, which are monitored by the state program office via site visits (seven states), paper survey review (one state), or both (seven states). Eight states license SBHCs as health-care facilities.

State policy on contraceptive access in SBHCs

With their early history steeped in adolescent pregnancy prevention, SBHCs are sometimes embroiled in controversy about on-site contraceptive access. As highlighted in the 1986 CPO report, anti-SBHC activists sought to restrict contraceptive access through the state legislative arena. According to the survey responses, five of the 19 states with SBHC initiatives (Delaware, Louisiana, Michigan, New Jersey, and Texas) prohibit their grantees from dispensing contraception on-site. An additional six states (District of Columbia, Georgia, Nevada, Ohio, Utah, and Virginia) restrict contraceptive access in SBHCs, despite the fact that they do not fund or regulate them.

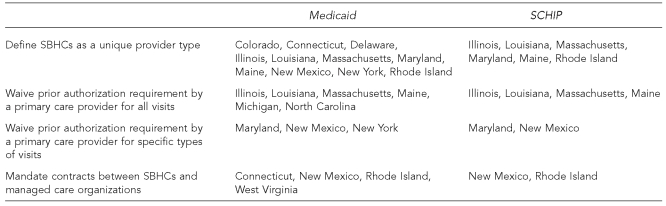

Medicaid and SCHIP

The growth of state SBHC investments throughout the 1990s corresponded with another fast-growing health-care finance phenomenon: Medicaid managed care. The dominance of managed care was later reinforced in 1998 with the emergence of SCHIP and managed care as the states' favored delivery mechanism.16 Thought critical by state stakeholders and advocates to long-term sustainability, reimbursement to SBHCs from Medicaid—and later, SCHIP—historically has been challenging for a host of reasons (both policy and capacity related) that have been documented by NASBHC.17 More than a decade after the introduction of managed care waivers, many of those challenges remain, but several of the states—exclusive to those with state-funded initiatives—have established policies to mandate or enable (but not always guarantee) reimbursement for services delivered in SBHCs to Medicaid and SCHIP enrollees. The four policies we found states most likely to implement were:

Define SBHCs as a unique provider type.

Waive prior authorization by a primary care provider for all visits.

Waive prior authorization by a primary care provider for specific types of visits (i.e., family planning, mental health, or acute care).

Mandate contracts between SBHCs and managed care organizations.

Figure 3 identifies states that have Medicaid and SCHIP policies for SBHCs. Assessing the impact associated with these reimbursement policies was not included in the scope of this research; however, a greater understanding of these policies on patient revenue recovery, and ultimately on SBHCs' fiscal sustainability, is needed.

Figure 3. State Medicaid/SCHIP policies.

SCHIP = State Children's Health Insurance Program

SBHC = school-based health center

DISCUSSION

In an evaluation of the RWJF state policy program Making the Grade, researchers Morone, Kilbreth, and Langwell noted that the spark of innovation driving SBHC initiatives “flew not up from the grassroots, but down from state government” led by “mavericks within state bureaucracies organizing the grassroots.”18 Our findings from the state survey reinforced the notion that the spark is well-maintained. As of 2005, 19 states had funding initiatives that included responsibilities for monitoring, oversight, and technical assistance, with the majority of these initiatives supporting a significant proportion of the total number of SBHCs in their state.

Unquestionably, state-level leadership has had a positive impact on the growth of SBHCs. Within these 19 states sit two-thirds of the nation's SBHCs, whether funded directly or not. Comparisons from the 2000 survey revealed that in four years, the number of SBHCs in states with initiatives increased by 26%, compared with 9% in states without initiatives. Moreover, when asked to identify attributes to current and historic levels of support, the survey respondents were as likely to identify advocacy within the state agency (17 of 19 states) as advocacy by grassroots (17 of 19 states). Although state initiatives are not necessary for SBHCs to flourish—a fact supported by the proliferation of SBHCs in Arizona, California, and Florida—they reinforce a standard of care and quality assurance, impart legitimacy with public and private insurers, seed interest in new programs, and reduce the burden of sustainability for local programs. SBHC advocates in a number of states (California, Ohio, Kentucky, and Washington) that have no leadership or dedicated resources within the state government have put the establishment of a state initiative high on their policy agenda.

However, one question remains: in light of ever-increasing competition for shrinking federal and state public health resources, can these state-level investments be continued? Traditional third-party capitation and fee-for-service reimbursement methods have failed to meet high expectations for sustaining SBHCs. Advocates argue that a reimbursement system based on historical underutilization of care from physicians in traditional single-discipline settings cannot fully support a more effective, comprehensive, coordinated, and responsive system of school-based primary care. Medicaid and SCHIP payment methodologies must be transformed to fully realize the promise of prevention and early intervention that is achieved with SBHCs, or alternative sources of revenue will need to be identified to sustain and grow this access model. It is well within the capacity of state government to do both.

CONCLUSION

Despite questions about future state-level investments, states have continuously invested in SBHC initiatives during the past 20 years. In 20 years, the number of state SBHC initiatives has increased from five to 19. Over time, these initiatives have played a significant role in the expansion of SBHCs by earmarking state and federal public health funding for SBHCs, stetting program standards, collecting evaluation data to demonstrate impact, and advocating for long-term sustainable resources.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kaplan DW, Calonge BN, Guernsey BP, Hanrahan MB. Managed care and school-based health centers: use of health services. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1998;152:25–33. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.152.1.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Juszczak L, Melinkovich P, Kaplan D. Use of health and mental health services by adolescents across multiple delivery sites. J Adolesc Health. 2003;32(6) Suppl:108–18. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(03)00073-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Santelli J, Kouzis A, Newcomber S. School-based health centers and adolescent use of primary care and hospital care. J Adoles Health. 1996;19:267–75. doi: 10.1016/S1054-139X(96)00088-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Key JD, Washington EC, Hulsey TC. Reduced emergency department utilization associated with school-based clinic enrollment. J Adolesc Health. 2002;30:273–8. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(01)00390-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Webber MP, Carpiniello KE, Oruwariye T, Lo Y, Burton WB, Appel D. Burden of asthma in inner-city elementary schoolchildren: do school-based health centers make a difference? Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2003;157:125–9. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.157.2.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guo JJ, Jang R, Keller KN, McCracken AL, Pan W, Cluxton RJ. Impact of school-based health centers on children with asthma. J Adolesc Health. 2005;37:266–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gall G, Pagano ME, Desmond MS, Perrin JM, Murphy JM. Utility of psychosocial screening at a school-based health center. J Sch Health. 2000;70:292–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2000.tb07254.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gall GB. Comprehensive risk assessment for adolescents in school-based health centers. Nurs Clin North Am. 2002;37:553–64. doi: 10.1016/s0029-6465(02)00016-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Price JH, Yingling F, Dake JA, Telljohann SK. Adolescent smoking cessation services of school-based health centers. Health Educ Behav. 2003;30:196–208. doi: 10.1177/1090198102251032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Galavotti C, Lovick SR. School-based clinic use and other factors affecting adolescent contraceptive behavior. J Adolesc Health Care. 1989;10:506–12. doi: 10.1016/0197-0070(89)90013-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Adams EK, Johnson V. An elementary school-based health clinic: can it reduce Medicaid costs? Pediatrics. 2000;105(4 Pt 1):780–8. doi: 10.1542/peds.105.4.780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Center for Population Options. School-based policy initiatives around the country. Washington: Center for Population Options; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lear JG, Eichner N, Koppelman J. The growth of school-based health centers and the role of state policies. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999;153:1177–80. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.153.11.1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schlitt JJ, Rickett KD, Montgomery LL, Lear JG. State initiatives to support school-based health centers: a national survey. J Adolesc Health. 1995;17:68–76. doi: 10.1016/1054-139X(95)00060-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Center for Health and Health Care in Schools. State surveys of school-based health centers. [cited 2008 Feb 11]. Available from: URL: http://www.healthinschools.org/Health-in-Schools/Health-Services/School-Based-Health-Centers/State-Surveys.aspx.

- 16.Center for Health and Health Care in Schools. Nine state strategies to support school-based health centers: executive summary. [cited 2008 Feb 11]. Available from: URL: http://www.healthinschools.org/static/papers/ninestrategies.aspx.

- 17.Schlitt J. Partners in access: school-based health centers and Medicaid. Washington: National Assembly on School-Based Health Care; 2001. [cited 2008 Feb 11]. Available from: URL: http://ww2.nasbhc.org/APP/Partners%20in%20Access%20Medicaid%20report.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morone JA, Kilbreth EH, Langwell KM. Back to school: a health care strategy for youth. Health Aff (Millwood) 2001;20:122–36. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.20.1.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]