SYNOPSIS

Objective.

School-based health centers (SBHCs) have proliferated rapidly, demonstrated success in health outcomes and access, and gained national recognition. Despite these accomplishments, organizational dissimilarities exist among health and school systems that are potentially leading to SBHC partnership barriers. This study sought to determine how partnering agencies promote cooperation and manage conflict across institutional boundaries.

Methods.

Utilizing case study methods, we conducted semistructured interviews of 55 stakeholders involved in program operations from four Massachusetts SBHCs. All had similar characteristics, yet based on a state-level rating system, two had successful interagency partnerships and two were experiencing difficulties.

Results.

Success designation played a role in how sites managed conflict and promoted understanding and cooperation. Data also revealed similarities such as frequent use of the term “guest” by all study subjects when describing SBHCs. School representatives stated that as guests, SBHCs should adhere to school rules. Health representatives assumed that as guests, they were not full partners and could be asked to leave. Successful sites were less likely to perceive themselves as guests. At successful sites, guest terminology also dissipated over time and evolved into interdependence and cooperation among school-health interagency partners.

Conclusion.

Viewing SBHCs as guests creates a tenuous partnership that may be counterproductive to SBHC growth and sustainability. Given current levels of public interest in education, SBHCs may afford enhanced attention to youth health. Additional financial and training resources are needed to build the common purpose that will encourage the formation and sustainability of strong, interdependent school-health partnerships.

School-based health centers (SBHCs) have proliferated rapidly throughout the U.S., demonstrated success in health outcomes, and improved health-care access for more than two million youth in 44 states.1 Yet, SBHCs have encountered challenges that have limited their growth and threatened long-term sustainability. Much discussion and research has occurred pertaining to more visible concerns confronting SBHCs such as financing, ideological opposition, and politics. However, little is known about organizational differences between health and education that some consider a significant contributing factor to SBHC challenges. While there is a rich literature on the factors that promote or inhibit successful school-community partnerships,2–9 it is broad in its notion of community and infrequently includes partnerships between schools and health care. It also does not specifically speak to SBHCs.

Establishing an SBHC requires the development of an interagency partnership between a school system and a health system. Despite a willingness to collaborate and integrate education and health services through SBHCs, educators and health professionals typically operate in distinct spheres with different organizational cultures and little overlap between them. They have differences in goals and perspectives, conditions of work, orientation of work, professional attributes, legal mandates, approaches to conflict, and funding mechanisms leading to potential partnership barriers,10–14 interdisciplinary conflict, and ineffective use of time for all involved. Hacker and Wessel assert that cultural differences between schools and health-care systems have made collaboration difficult.15 As a result, SBHCs may not be reaching their full potential.

A primary difference between traditional school-community partnerships and school-health partnerships through an SBHC is that SBHCs literally reside in the school for the long term, yet are often referred to as “guests.” As in any relationship, dynamics can change when things progress to the moving-in stage. New issues emerge that go beyond basic turf challenges and can escalate into deep conflicts and unwillingness to cooperate and collaborate. Despite these serious issues, SBHCs as an entity have not dealt with them in a coordinated way. Thus, more attention should be given to organizational differences between schools and health systems engaged in SBHC partnerships, as well as the impact of organizational issues on SBHC operations and partnership success.

Adelman and Taylor believe that informal school-community connections are simple to establish. However, developing comprehensive, long-term relationships is more challenging and necessitates multifaceted strategies. Only through formalized and institutionalized connections can success be achieved.16 Rogers states that forming school-community partnerships without paying attention to organizational differences, responsibilities, accountabilities, and liabilities can exacerbate strain.17 Melaville and Blank recommend that despite challenges, education, health, and human services must join forces as co-equals in service delivery rather than each struggling to meet every need.2 Zahner suggests additional research on interagency partnerships as a strategy for public health improvement.18 Lear states that notwithstanding real and longstanding partnership barriers, “the time is ripe” for school-health partnerships.19

Despite organizational challenges inherent in school-health partnerships, some SBHCs are flourishing while others are failing to thrive. This study was designed to understand this dichotomy by answering the question, “Are there variations in the ways that particular SBHCs and their sponsoring agencies in one state (Massachusetts) manage conflict and promote understanding and cooperation across institutional boundaries?”

METHODS

Study design and data collection

The study utilized a multiple case design. Case study methods are appropriate to explore interagency partnerships because they consider both the voice and perspective of the actors and groups of actors and their interaction.20 Case studies are also prevalent in education-related settings and offer a vehicle to identify and explain specific issues and problems.21

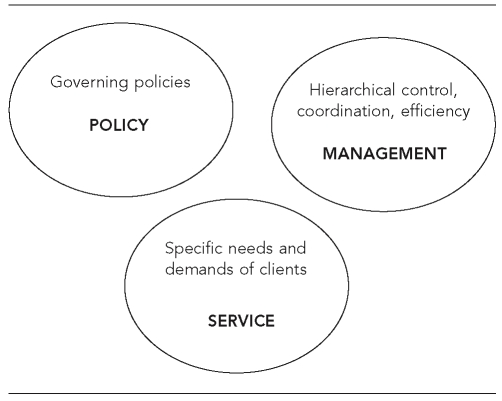

Data collection was guided by Domain Theory, which offered a framework to examine organizational operations in human service agencies, such as schools and health systems, and served as a diagnostic tool to assess organizational health of the interagency partnerships. In particular, Domain Theory examines divisions of labor or domains within and between human service organizations and explores differences in orientation and interactions between domains, as well as strategies to minimize conflict between them (Figure 1).22

Figure 1. Domain theorya.

aKouzes JM, Mico PR. Domain theory: an introduction to organizational behavior in human service organizations. J App Behav Science 1979;15:449-69. Adapted from unpublished classnotes of J. Chilingerian, Brandeis University, 2005.

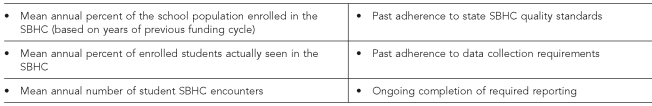

Four Massachusetts schools with SBHCs were selected as the primary cases for this study and were purposefully selected to compare organizational features associated with their success status. Two of the SBHCs were more successful and two were less successful based on a state-developed past-performance rating system. The SBHC past-performance rating scale was used as part of a competitive funding cycle process to assess regulatory compliance of individual state-funded SBHCs and to help determine future funding levels. Detailed criteria considered in the rating scale are provided in Figure 2. Based on this scale, three rating levels (excellent, moderate, and needs improvement) were issued.23 For the purposes of this study, SBHC sites that received an “excellent” rating were deemed more successful and those that were dubbed “needs improvement” were considered less successful. Further, while the state assessment was based solely on regulatory compliance, this study sought to examine additional programmatic features to determine whether or not they also contributed to program success.

Figure 2. State past-performance rating criteria.

SBHC = school-based health center

Efforts were made to select cases that were very similar in terms of community demographics, patient population, service elements, and years of operation. The same research methods were duplicated from case to case such that if findings were consistent across cases, they could be considered more robust.24

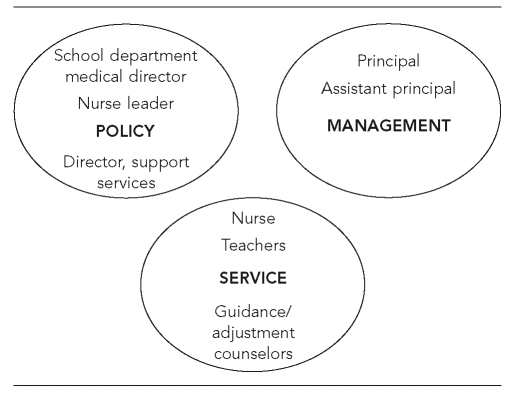

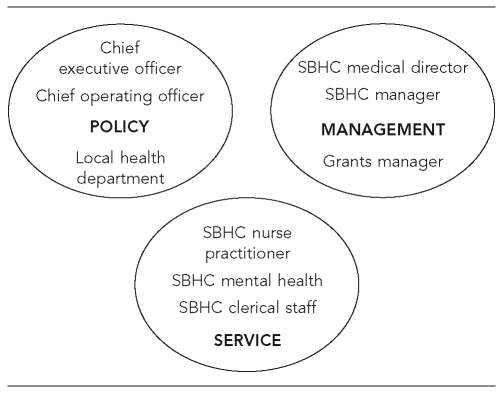

Four types of data were collected between March and June 2005: semistructured interviews, meeting observation, document review, and field notes. However, for the purposes of this article, interview data were predominantly reported. An interview guide was used with key stakeholders from both school and health-care systems. Sampling for interviews was based on Domain Theory parameters and sought to include people from each domain and each organizational system within all four case studies: education policy, education management, education service and health policy, health management, and health service (Figures 3 and 4).

Figure 3. Sampling education system.

Figure 4. Sampling health system.

SBHC = school-based health center

Interviewees were asked questions that included their understanding of interagency partnership operations, partnership history, how differences between agencies are addressed and resolved, and their suggestions and recommendations for the future. Audiotaped interviews lasted between 30 and 45 minutes, and detailed field notes were written after each interview.

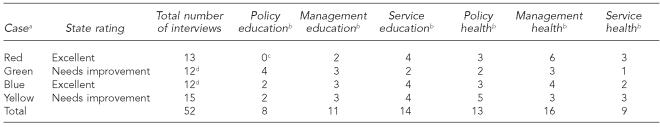

Eleven to 15 interviews were conducted per case for a total of 52 interviews with 55 stakeholders. The Table offers details with regard to the interviews at each site.

Table. Interviewees in each case by domain and agency type.

aActual names of sites are not included. Colors are used as a proxy.

bSome people considered themselves part of more than one domain.

cThe red and green sites are in the same city, hence the same school department. However, school-based health centers are operated by different health-care organizations. Therefore, all education policy interviews were recorded on the green site, but pertain to both red and green.

dNursing supervisors at both the green and blue sites asked to be interviewed in a group. Thus, they were technically counted as one interview each but actually had three people in the green site and two in the blue.

Data analysis

Data analysis followed qualitative methods procedures outlined in Miles and Huberman,25 as well as case study methods outlined in Yin.24 All data were transcribed and placed into Atlas ti, a software package for qualitative analysis of textual, graphical, audio, and video data.26

To facilitate an explanation of findings, all data were then broken down into short sets of descriptive words applied to segments of data (coding).27 Data coding took place in several stages beginning with a start list of codes and definitions based on the study question and theoretical framework. Codes were then added as they emerged from the data themselves. Documents were grouped by demographics (school, health agency, populations served), case study, domain, system (health or education), success status, and data type (interviews, observations, document review, and field notes). Next, data groupings were queried and code frequencies were tabulated and reviewed. Case descriptions were used to describe, explain, and organize the data. Unique patterns of each case were documented prior to generalizing patterns across cases. Cross-case synthesis was finally employed as a means to more closely examine and explain similarities and differences between the cases.

RESULTS

There were marked differences between how more successful and less successful sites managed conflict and promoted understanding and cooperation. Generally, more successful SBHC cases demonstrated shared goals between the school and health system, formal communication structures, interdependence between school and SBHC, SBHC staff longevity, and involved leadership. Less successful cases were more likely to have historical interagency conflict, competing priorities among key stakeholders, turf issues, reactive communication structures, high SBHC staff turnover, and passive leadership. Many of these findings are more thoroughly addressed elsewhere.28

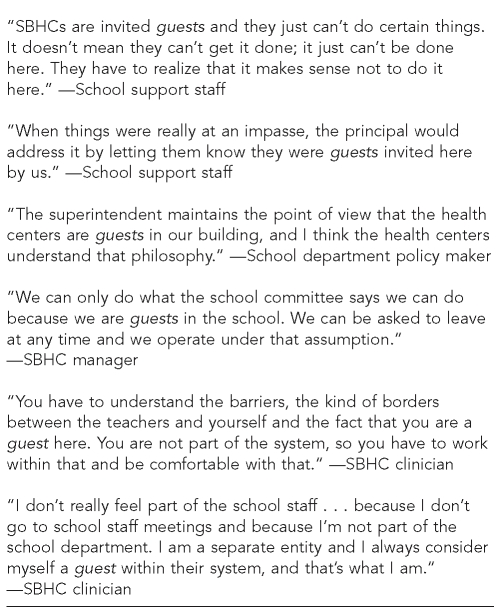

However, there were some similarities among the cases that were especially compelling and unanticipated. One such finding was the frequent use of the term “guest” when all subjects from both school and health systems described the SBHCs in which they were associated. School representatives stated that as guests, SBHCs needed to adhere to school rules. Similarly, health representatives assumed that as guests they were not full partners and could be asked to leave the school at any time (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Guest quotes.

SBHC = school-based health center

This terminology was discovered among all four cases, from all domains, and from both health and education systems. However, subjects from the more successful sites tended to utilize this guest reference less often. Further, those interviewees from the more successful sites and with a historical perspective of the SBHC partnership stated that the guest references tended to mitigate over time, particularly among those from the service-level domains, and evolved into a greater sense of interdependence among the interagency partners.

DISCUSSION

Genesis of “guest” terminology

Several subjects explained how the guest concept began. It was viewed as a legacy from the 1970s when SBHCs were just emerging across the country. At that time, health agencies interested in operating SBHCs not only had to convince school systems of the need and potential efficacy for such services, but also had to make a case for a school system to relinquish already limited space for such programs. Some SBHC services were also deemed controversial based on the types of services they might offer. Consequently, SBHC advocates had to make many compromises and assurances to even be allowed into a school building. Furthermore, because most SBHCs did not have the resources to pay rent, school systems were technically lending them space that was temporarily available. Thus, the notion of being a “guest” in the school building was established. State funding agencies later perpetuated the guest notion by encouraging SBHC staff to tread lightly in the school building to avoid any controversy.

Another reason for the use of the term “guest” when referring to SBHCs was that offering comprehensive medical services in a facility that had a sole tradition of providing education was counterintuitive to most. Therefore, some could not accept that this concept was anything more than a short-term aberration. Still others from the educational systems referred to SBHCs as guests because of the perception that SBHC staff members were outsiders with different training and different goals. Thus, distrust and xenophobia existed.

Impact of guest perception on SBHC success and sustainability

Interview subjects from the health arena spoke of the challenges of being guests in the school. They felt that they needed to always be on their best behavior. They spoke of the constant fear of being thrown out. SBHC direct service staff found this notion to be anxiety producing in terms of meeting their sponsoring agency goals and retaining jobs. They were also leery about introducing new initiatives and growing the program. The guest perception also appeared to weaken school and community collaboration with the SBHC because of concern that the SBHC could be taken away easily.

Several subjects believed that guest status emphasized differences between health and education, and exacerbated conflict between school and SBHC staff because of resentment over SBHCs staying longer than the typical guest and not always abiding by all the host's rules. Some stated that school personnel would occasionally coerce compliance by reminding SBHC staff of their guest status. Many also stated that with the increased prominence of school accountability mandates came increased tensions between schools and SBHCs.

The use of guest terminology also influenced management and policy-level staff from SBHC-sponsoring health agencies that were reluctant to fully institutionalize a program that could be so easily dissolved. They challenged the logic of investing organizational resources into a facility that they neither owned nor controlled.

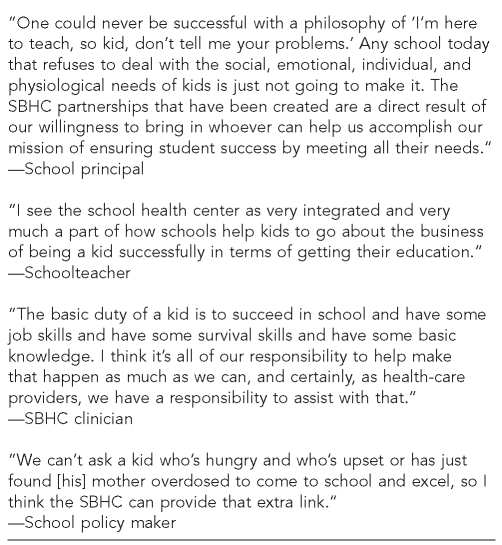

Best guest practices

Some key differences displayed by the more successful sites appeared to help them meet the challenges posed by the pervasive guest mentality. For example, the education stakeholders expressed an overall philosophy that they needed to do whatever was necessary to help students succeed. They were cognizant of the school's limitations and welcomed assistance from the community. Principals from these sites shared numerous ways in which their SBHC had helped the school achieve its educational mission. Thus, the more successful sites adopted a sense of interdependence between the school and the SBHC as a strategy to better assist students (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Quotes demonstrating interdependence.

SBHC = school-based health center

Educators from the more successful sites were more likely to repeatedly collaborate with SBHC staff and express satisfaction with the outcome of the collaboration. These teachers then tended to share positive experiences with other faculty.

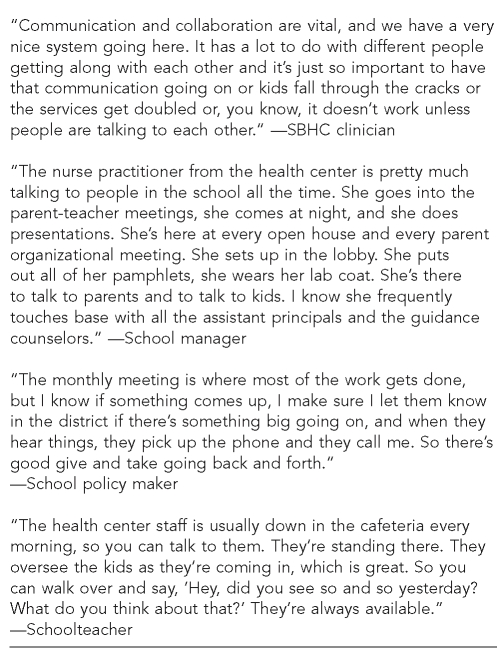

At the more successful sites, SBHC direct service staff and managers made concerted, ongoing efforts to build rapport with teachers and other school staff. They were mindful of the school needs and strived to respond accordingly. They discovered that being in the school enabled access to the most at-risk students who were unlikely to obtain health care in any other venue. Finally, they were more likely to accept their guest status and work within its confines, complying with school rules and actively participating in school-wide events (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Quotes demonstrating rapport-building and communication strategies.

SBHC = school-based health center

Overall, more successful SBHCs were more likely than their less successful counterparts to have systems in place that provided a cooperative communication context that facilitated working out differences, helping partners better understand each other, and creating opportunities for enhanced collaboration, thereby lessening guest status issues.

Study limitations

There were several limitations of this study. While the research offered an in-depth look at SBHC organizational issues, it only examined four SBHCs in one state, thereby precluding generalizability. Future studies should be conducted in broader SBHC arenas.

There were limitations of interview data in that they did not give direct access to how people performed daily activities.19 Interviews only offered the subject's perspective at a particular point in time. The ability to conduct observations and review written documents helped to mitigate this limitation.

While the use of qualitative techniques may have limited the size of the study, they enabled discoveries that would not have been possible with quantitative approaches. More qualitative studies are recommended to better understand SBHC organizational issues.

CONCLUSION

This study reinforced the need to raise awareness for SBHCs, their sponsoring schools and health systems, advocacy groups, and government agencies of organizational issues and their relationship to interagency conflict and partnership success. This study also concurred with much of the literature on school-community partnerships. There were, however, unique distinctions with partnerships involving SBHCs vs. other types of school-community partnerships, such as the designation of guest status. This author believes the guest status finding implies that a partnership is temporary, tenuous, and may exacerbate conflict. Guests who overstay their welcome are viewed unfavorably. This impermanent partnership notion may be counterproductive to SBHC growth and sustainability.

Following are several recommendations that may mitigate the usage and impact of guest status.

Guest status may be diminished if professional development opportunities sponsored by national associations and typically aimed at health or education professionals broaden their focus and outreach to audiences that include both groups. Another avenue for improvement is to work with professional schools of medicine, nursing, social work, public health, and education to include more training on the need for and benefit of interdisciplinary work between the fields.

State public health departments that fund SBHCs can help diminish SBHC guest perception by: (1) modeling collaborative behavior with state education departments, (2) sponsoring joint professional development for SBHC and school staff, (3) prioritizing interagency collaboration and cooperation, and (4) offering technical assistance and funding for building and sustaining SBHC partnerships. They can also include documented school-health collaboration as a condition of SBHC funding. However, other research has discovered that funding mandates are not necessary for interagency partnerships to be successful.18

On a local level, superintendents and principals need to offer more opportunities that bring SBHC and school personnel together in meaningful, collaborative ways. School systems can also encourage teachers, administrators, and principals to have more active involvement in the SBHC partnership by providing the time and resources to do so.

SBHC and sponsoring health agency staff can make more effort to integrate with schools by attending school meetings, joining committees, teaching classes, and helping other school health staff. The key is to build rapport, common purpose, and interdependence.

Given current levels of public interest in education, SBHCs may afford enhanced attention to youth health. Additional resources are needed to build the common purpose that will encourage the formation and sustainability of strong, interdependent school-health partnerships.

REFERENCES

- 1.National Assembly on School-Based Health Care. Financing. [cited 2007 Jul 15]. Available from: URL: http://www.nasbhc.org/site/c.jsJPKWPFJrH/b.2561561/k.CE06/funding.htm#Funding_Data.

- 2.Melaville AI, Blank MJ. What it takes: structuring interagency partnerships to connect children and families with comprehensive services. Washington: The Education and Human Services Consortium; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stegelin DA, Jones SD. Components of early childhood interagency collaboration: results of a statewide study. Early Education and Development. 1991;2:54–67. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Paavola JC. Health services in the schools: building interdisciplinary partnerships. Greensboro (NC): ERIC Clearinghouse on Counseling and Student Services; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schorr L. Common purpose: strengthening families and neighborhoods to rebuild America. New York: Anchor/Doubleday; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 6.O'Looney J. Modeling collaboration and social services integration: a single state's experience with developmental and non-developmental models. Administration in Social Work. 1994;18:61–86. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mullett J, Jung K, Hills M. Collaboration in nonprofits: dynamics and dilemmas. Canadian Review of Social Policy. 2002;49(50):155–73. [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Assembly of Health and Human Service Organizations. Dimensions of school/community collaboration: what it takes to make collaboration work. Washington: National Assembly of Health and Human Service Organizations; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johnson LJ, Zorn D, Tam BKY, Lamontagne M, Johnson SA. Stakeholders' views of factors that impact successful interagency collaboration. Exceptional Children. 2003;69:195–209. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Messinger K, Nader P, Parcel G, Porter P, Williamson M. School health vs. health in the school: integrating medical and educational models. In: Nadar PR, editor. Options for school health: meeting community needs. Germantown (MD): Aspen Publications; 1978. pp. 27–58. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lavin AT, Shapiro GR, Weill KS. Creating an agenda for school-based health promotion: a review of 25 selected reports. J Sch Health. 1992;62:212–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.1992.tb01231.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Theis KM, Krawczyk RM, Gaspard N. Issues in the school health and expanding partnerships. In: Tourse RWC, Mooney JF, editors. Collaborative practice: school and human service partnerships. Westport (CT): Praeger Publishers; 1999. pp. 155–80. [Google Scholar]

- 13.St.Leger L, Nutbeam D. A model for mapping linkages between health and education agencies to improve school health. J Sch Health. 2000;70:45–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2000.tb07239.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jehl J, Blank M, McCloud B. Education and community building: connecting two worlds. Washington: Institute for Educational Leadership; 2001. [cited 2004 May 31]. Also available from: URL: http://www.communityschools.org/combuild.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hacker K, Wessel GL. School-based health centers and school nurses: cementing the collaboration. J Sch Health. 1998;68:409–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.1998.tb06318.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Adelman H, Taylor L. School community partnerships: a guide. Los Angeles: School Mental Health Project, University of California, Los Angeles; 2002. [cited 2004 Apr 15]. Also available from: URL: http://smhp.psych.ucla.edu/pdfdocs/guides/schoolcomm.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rogers G, Este D, Tymchyshyn D, Matheson J, Lawson A, Egers J. Partnerships in nonprofit children's services: panacea or pitfall?. the Association for Research on Nonprofit Organizations and Voluntary Action (ARNOVA) Conference; Nov 20–22; Denver. 2004. Paper presented at. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zahner SJ. Local public health system partnerships. Public Health Rep. 2005;120:76–83. doi: 10.1177/003335490512000113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lear JG. Health at school: a hidden health care system emerges from the shadows. Health Aff (Millwood) 2007;26:409–19. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.26.2.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tellis W. [cited 2004 Apr 19];Introduction to case study. The Qualitative Report. 1997 3 Also available from: URL: http://www.nova.edu/sss/QE/QE3-2/tellis1.html. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Merriam SB. Qualitative research and case study applications in education. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kouzes JM, Mico PR. Domain theory: an introduction to organizational behavior in human service organizations. J App Behav Science. 1979;15:449–69. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Massachusetts Department of Public Health. Request for response: school-based health center program #447. 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yin RK. Case study research: design and methods. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage Publications; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miles MB, Huberman M. Qualitative data analysis: a source book of new methods. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage Publications; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Muhr T, Friese S. User's manual for ATLAS ti 5.0. 2nd ed. Berlin: Scientific Software Development; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lofland J, Lofland LH. Analyzing social settings: a guide to qualitative observation and analysis. 3rd ed. Belmont (CA): Wadsworth Publishing Co.; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mandel LA. Doing what it takes: the impact of organizational issues on Massachusetts school-based health center success. Ann Arbor (MI): ProQuest/UMI; 2007. [cited 2008 Jun 13]. UMI No. 3259732. Also available from: URL: http://proquest.umi.com/pqdlink?did=1331412191&Fmt=7&clientI d=79356&RQT=309&VName=PQD. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Coffey AJ, Atkinson PA. Making sense of qualitative data: complementary research strategies. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage Publications; 1996. [Google Scholar]