The availability of prophylactic cancer vaccines introduces new opportunities to prevent disease and improve the health status of individuals and communities. Recently, state legislatures throughout the U.S. have considered whether to require the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination for school entry. The debate raises novel questions for policy makers who find themselves confronted with a dilemma that rests at the intersection of law, the right to personal autonomy, and matters of population health. This installment of Law and the Public's Health examines the question of school entry immunization mandates in the context of HPV vaccine.

BACKGROUND

The mandatory immunization of the population has been a seminal issue in public health law for nearly two centuries. At the state level, the legal authority to require immunization rests on states' 10th Amendment “police powers,” which can be used to effectively convert public health recommendations into legally enforceable obligations. States can exercise this power directly or delegate their powers to local governments. Government immunization mandates have withstood multiple challenges grounded in a variety of legal theories including claims that compulsory immunization laws constitute an illegal search and seizure under the Fourth Amendment,1 a violation of the 14th Amendment Equal Protection Clause,2 or a violation of the First Amendment's prohibition against religious establishment.3 Courts repeatedly have affirmed a state's right to develop measures that “protect the health and safety” of its citizens4 and the constitutionality of school entry requirements.5

The first school entry immunization mandate can be traced to 1827, when the city of Boston required students to be inoculated against smallpox.6 Today, all states and the District of Columbia (DC) require students to demonstrate that they have received certain immunizations before they are permitted to attend school. These measures have proven to be the most effective tool ever devised to protect children and their families from the effects of vaccine-preventable disease. Although states vary in how vigorously the mandates are enforced, the laws have increased coverage rates among all children, reduced racial and ethnic disparities among school-age children, and decreased the incidence of infectious disease.7 Increased access to immunizations has been documented for children who live in low-income families, those who have been unable to establish a medical home, as well as those who would not otherwise have access to these services.8,9

While school vaccination mandates are universal requirements that assume compliance, all jurisdictions include “opt-out” provisions that permit parents to refuse immunizations for their children. Parents may exercise their right to refuse vaccination for one of three reasons, depending on the state. All states and DC grant exemptions for medical contraindication when it can be reasonably predicted that a child would experience adverse effects from a vaccination; 47 states and DC permit refusal based on a claim that a religious belief opposes vaccination; and 18 states allow exemptions based on a parent's personal, moral, or philosophical beliefs.10

Despite the availability of opt-outs, more than 95% of school-age children receive mandated immunizations and less than 1% of parents nationwide reject vaccines.11 These low rates safeguard “herd immunity;” that is, the resistance to a disease that develops in an entire community when a sufficient number of individuals are vaccinated. Herd immunity protects those few individuals who are unable to receive vaccinations due to age or health status.

Some states have developed simple procedures that make exemptions easy to obtain. These states are, not surprisingly, associated with decreased coverage rates and higher incidence of disease when compared with states that do not offer easy options and states that have developed more difficult opt-out procedures.12

HPV INFECTION AND VACCINE

HPV is the most common sexually transmitted infection in the U.S.; more than 20 million individuals are currently affected. Infection with HPV usually develops within two years of sexual debut and nearly all women will have contracted genital HPV infection by age 50. Of the more than 100 strains of HPV, 16 and 18 cause approximately 70% of cervical cancer and 6 and 11 are responsible for 90% of genital warts. Gardasil® is the first vaccine to protect against strains 6, 11, 16, and 18. The vaccine is a prophylactic, conferring almost 100% protection for a minimum of five years. Because the vaccine is most effective if administered before exposure to the infection, female children aged 11 and 12 are considered to be the primary target population.13

Historically, vaccine mandates have targeted diseases that are transmitted through casual contact, resulting in immediate outbreaks. These diseases are characterized by high morbidity or mortality, particularly among children who die from vaccine-preventable disease at a disproportionately higher rate when compared with adults. The HPV vaccine is different; it targets infections that are transmissible through intimate skin-to-skin contact, and the resulting disease may not develop until several decades after initial exposure.

REGULATORY AND LEGISLATIVE RESPONSE TO HPV VACCINE

In June 2006, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) licensed Gardasil. Subsequently, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) recommended administration of the vaccine to females aged 9 through 26. Routine immunization of younger females, aged 11 and 12, was recommended.14 ACIP is a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)-administered commission whose recommendations create the national standard of care for vaccine delivery.

An ACIP recommendation triggers government and private programs that are designed to increase access to vaccines among appropriate populations. Public programs that ensure the availability of vaccines include the Vaccines for Children Program, Medicaid, 317 grant programs, and state and local delivery mechanisms. Private-market health insurance plans may rely on ACIP recommendations to make coverage decisions. Finally, states often modify the list of vaccines that are required for school entry to comply with administration schedules developed by ACIP.

During the 2006–2007 legislative sessions, 27 states and DC considered whether to require Gardasil for school entry, usually prior to entering grade 6.15 Opponents presented several arguments, claiming that the vaccine is not a good candidate for a mandate because: (1) HPV infection is not casually communicable as are most of the diseases included in school mandates; (2) a mandate would provide tacit approval of promiscuity among teens; (3) the vaccine targets a disease that has a long incubation period and would affect a small number of individuals long after they left school; (4) the vaccine is too costly and would consume limited government resources; (5) the vaccine may be unsafe and ineffective; (6) vaccine requirements infringe on parents' rights to make medical decisions for their children without unwarranted government interference; and (7) special, broad opt-out provisions should be included for parents who wish to decline the vaccine for any reason.

HPV SCHOOL ENTRY REQUIREMENTS IN DC AND VIRGINIA

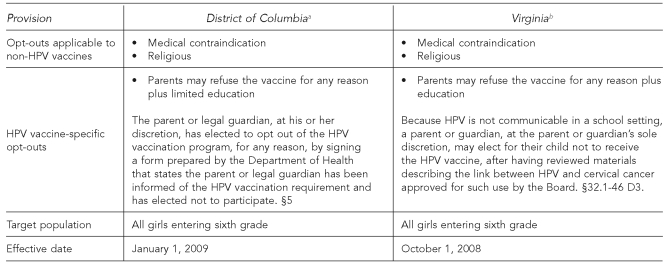

To date, only DC and Virginia have enacted legislation requiring all girls entering the sixth grade to be vaccinated against HPV.16 DC's mandate is effective in 2009 and Virginia's law is effective in 2008. Each state permits two exemption possibilities for all required vaccines: for medical or religious reasons.

However, specific to HPV vaccine, both jurisdictions have expanded opportunities for parents or guardians to refuse vaccination for their daughters. DC permits parents to decline the vaccine “for any reason.”17 In Virginia, at the “parent or guardian's sole discretion,” he or she “may elect for their child not to receive the … vaccine, after having reviewed materials describing the link between [HPV] and cervical cancer.”18 This broad refusal right is permitted “[b]ecause [HPV] is not communicable in a school setting.”19 The Figure summarizes how these provisions compare.

Figure. District of Columbia and Virginia school mandate opt-out provisions.

aThe HPV Vaccination Reporting Act of 2007, Bill B17-30

bAn Act to amend and reenact §32.1-46 of the Code of Virginia, relating to requiring HPV vaccine

HPV = human papillomavirus

IMPLICATIONS FOR PUBLIC HEALTH POLICY AND PRACTICE

As both basic personal health care and essential public health activities with population-wide health implications, vaccines and recommended immunizations are among the greatest achievements of public health. These interventions have saved more lives than any surgical technique or any medication, including antibiotics.20

State laws that require vaccination as a condition for school attendance are critical elements of an effective vaccine delivery system. These policies translate national recommendations into immunization practice and increased access to vaccines. Over time, school mandates have created the impetus for increased coverage rates. However, the HPV vaccine poses unanticipated challenges to the existing legal landscape. While the vaccine introduces new opportunities to control and prevent disease, parental concerns endure. Apprehensions regarding the appropriateness of the vaccine have been coupled with general concerns about vaccine safety, effectiveness, cost, and parental rights.

Policy makers must determine whether school mandates will continue to be utilized to convert new vaccine technology into health services delivery. While both DC and Virginia have permitted broad opt-out rights, the inclusion of educational requirements could serve two purposes: (1) alleviate much of the concern associated with HPV, sexuality and youth, and immunization, and (2) encourage informed decision-making before parents can refuse the vaccine. Education could prove to be the much-needed bridge to compliance. In these instances, policy makers have attempted to balance effective policy with effective politics to obtain effective outcomes.

REFERENCES

- 1. McSween v. Board of School Trustees, 129 S.W. 206 (Tex. Civ. App.)

- 2. Adams v. City of Milwaukee, 228 U.S. 572.

- 3. Mason v. General Brown Cent. Sch. Dist., 851 F.2d 47 (2d Cir.)

- 4. Jacobsen v. Com. of Massachusetts, 197 US 11 (1905) at 25.

- 5. Zucht v. King, 260 US 174 (1922)

- 6.Hodge JG, Jr., Gostin LO. School vaccination requirements: historical, social, and legal perspectives: a state of the art assessment of law and policy. Baltimore: Center for Law and the Public's Health at Johns Hopkins and Georgetown Universities; 2002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Orenstein WA, Hinman AR. The immunization system in the United States—the role of school immunization laws. Vaccine. 1999;17(3):S19–S24. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(99)00290-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shefer A, Briss P, Rodewald L, Bernier R, Strikas R, Yusuf H, et al. Improving immunization coverage rates: an evidence-based review of the literature. Epidemiol Rev. 1999;21:96–142. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a017992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Briss PA, Rodewald LE, Hinman AR, Shefer AM, Strikas RA, Bernier RR, et al. Reviews of evidence regarding interventions to improve vaccination coverage in children, adolescents, and adults: The Task Force on Community Preventive Services. Am J Prev Med. 2000;18(1) Suppl:97–140. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(99)00118-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases (US) Childcare and school immunization requirements: 2005–2006. [cited 2008 Jul 14]. Available from: URL: http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/vac-gen/laws/downloads/izlaws05-06.pdf.

- 11.Hodge JG., Jr. School vaccination requirements: legal and social perspectives. National Conference of State Legislatures State Legislative Report. 2002;27:1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Omer SB, Pan WK, Halsey NA, Stokley S, Moulton LH, Navar AM, et al. Nonmedical exemptions to school immunization requirements: secular trends and association of state policies with pertussis incidence. JAMA. 2006;296:1757–63. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.14.1757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Quadrivalent human papillomavirus vaccine: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) MMWR Recomm Rep. 2007;56(RR-2):1–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US) CDC's Advisory Committee recommends human papillomavirus virus vaccination [press release] 2006. Jun 29, [cited 2008 Jul 11]. Available from: URL: http://www.cdc.gov/od/oc/media/pressrel/r060629.htm.

- 15.Women in Government. The “state” of cervical cancer prevention in America—2008. [cited 2008 Jul 11]. Available from: URL: http://www.womeningovernment.org/files/file/prevention/statereports/2008/ReportFindings.pdf.

- 16. The HPV Vaccination Reporting Act of 2007, Bill B17-30.

- 17. D.C. Code §7-1651.04 (b)(1)(B)(iii) (2008)

- 18. Va. Code Ann. § 32.1-46 (D)(3) (2008)

- 19. § 32.1-46 (D)(3)

- 20.Ten great public health achievements—United States, 1900–1999. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1999;48(12):241–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]