Abstract

Aims

Growth-differentiation factor-15 (GDF-15) has emerged as a biomarker of increased mortality and recurrent myocardial infarction (MI) in patients diagnosed with non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndrome. We explored the usefulness of GDF-15 for early risk stratification in 479 unselected patients with acute chest pain.

Methods and results

Sixty-nine per cent of the patients presented with GDF-15 levels above the previously defined upper reference limit (1200 ng/L). The risks of the composite endpoint of death or (recurrent) MI after 6 months were 1.3, 5.1, and 12.6% in patients with normal (<1200 ng/L), moderately elevated (1200–1800 ng/L), or markedly elevated (>1800 ng/L) levels of GDF-15 on admission, respectively (P < 0.001). By multivariable analysis that included clinical characteristics, ECG findings, peak cardiac troponin I levels within 2 h (cTnI0–2 h), N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide, C-reactive protein, and cystatin C, GDF-15 remained an independent predictor of the composite endpoint. The ability of the ECG combined with peak cTnI0–2 h to predict the composite endpoint was markedly improved by addition of GDF-15 (c-statistic, 0.74 vs. 0.83; P < 0.001).

Conclusion

GDF-15 improves risk stratification in unselected patients with acute chest pain and provides prognostic information beyond clinical characteristics, the ECG, and cTnI.

Keywords: Growth-differentiation factor-15, Acute chest pain, Risk stratification, Biomarker

Introduction

Rapid evaluation of patients with acute chest pain remains a common challenge. The purpose of early triage is not only the detection of acute myocardial infarction (MI), but also identification of other urgent conditions. In addition, stratification concerning the risk for subsequent adverse events is a main goal of performed tests and procedures. The overall objective of early triage is to allow targeting of patients at high risk to appropriate levels and types of health care, including early implementation of treatments known to reduce morbidity and mortality. Patients at low risk also need early identification to allow saving of resources by early discharge and further evaluation in outpatient settings.1,2 Apart from the patient’s history and physical findings, prognostic assessment of patients with acute chest pain is based on ECG registration and measurement of biomarkers of myocardial necrosis (e.g. the cardiac troponins) which, when abnormal, indicate an increased risk of adverse events.3–5

Growth-differentiation factor-15 (GDF-15) is a stress-responsive member of the transforming growth factor-β cytokine superfamily. In animal models, GDF-15 is induced in the heart in response to ischaemia–reperfusion injury, pressure overload, and heart failure, possibly via pro-inflammatory cytokine and oxidative stress-dependent signalling pathways.6,7 We have recently reported that the circulating levels of GDF-15 are increased and independently associated with mortality, risk of recurrent MI, and the effects of early invasive procedures in patients diagnosed with non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndrome.8,9

As these data were derived from highly selected, high-risk populations enrolled in clinical trials, the usefulness of GDF-15 for risk stratification needed to be evaluated in a heterogeneous, non-selected, real-life patient cohort with chest pain. We therefore assessed the circulating level of GDF-15 and its relation to clinical risk indicators, other biomarkers, and outcome in patients with acute chest pain from the FAST II (Fast Assessment of Thoracic Pain) and FASTER I (Fast Assessment of Thoracic Pain by Neural Networks) studies.

Methods

Study design

The present investigation is a substudy from the FAST II and FASTER I trials in patients admitted to the coronary care unit with acute chest pain. FAST II was conducted at Uppsala University Hospital between May 2000 and March 2001.10 The FASTER I trial included patients at three centres in Sweden between October 2002 and August 2003.11 Patients were eligible if admitted with chest pain suggestive of an acute coronary syndrome and lasting for ≥15 min within the last 24 h (FAST II) or 8 h (FASTER I). In both studies, ST-segment elevation in the admission 12-lead ECG leading to immediate reperfusion therapy or its consideration was the only exclusion criterion. Blood samples were obtained on admission, after 30–40 and 80–90 min and after 2, 3, 6, and 12 h for immediate analysis of cardiac troponin I (cTnI). In case of a clinical suspicion of an acute MI (FAST II) or any cTnI elevation ≥0.1 µg/L within the first 12 h (FASTER I), a last cTnI measurement was obtained after 24 h. Additional EDTA plasma samples obtained on admission were stored frozen in aliquots at −70°C for later determination of other biomarkers. All patients received standard medical therapy; the need for revascularization was determined by the treating physicians. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients and the study protocol was approved by the local Ethics Committees. For the present study, 169 patients from the FAST II trial and 310 patients from the FASTER I trial with symptom onset within 8 h before admission, first time admission, and availability of plasma samples were included.

Laboratory analyses

The concentration of GDF-15 was determined by immunoradiometric assay.12 Patients were stratified based on two pre-specified GDF-15 cut-off levels, 1200 ng/L and 1800 ng/L. As previously shown, 1200 ng/L corresponds to the upper limit of normal in apparently healthy, elderly Swedish individuals.12 In a previous study in patients with confirmed non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndrome, 1200 and 1800 ng/L corresponded to the lower and upper tertile boundaries and allowed for an identification of patients at low (<1200 ng/L), intermediate (between 1200 and 1800 ng/L), or high risk (>1800 ng/L).8

cTnI was analysed serially at the point of care using Stratus CS instruments (Dade Behring, Deerfield, IL, USA). For the Stratus CS cTnI assay, the 99th percentile among healthy individuals is 0.07 µg/L, the lowest concentration assuring an analytical imprecision (CV) of <10% is 0.1 µg/L.13 N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) was determined with a sandwich immunoassay on an Elecsys 2010 instrument (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany). C-reactive protein was analysed with a chemiluminescent enzyme-labelled immunometric assay on an Immulite 1000 analyser (Diagnostic Products Corp., Los Angeles, CA, USA). Cystatin C was measured using a latex-enhanced reagent and a BN ProSpec analyser (Dade Behring).

ECG analysis

A resting 12-lead ECG was obtained on admission and interpreted by an independent investigator unaware of the patient’s clinical outcome. ST-segment depression was defined as a downward deviation of the ST-segment of ≥0.05 mV below the isoelectric line in any lead. T-wave inversion was considered present when a negative or isoelectric T-wave was found in leads I, II, or V2–V6, in lead aVL if the amplitude of the R-wave was >0.5 mV, or in lead aVF if the QRS-amplitude was mainly positive. Patients without sinus rhythm, with pathological Q-waves (duration >0.03 s and an amplitude >25% of the following R-wave amplitude), left bundle branch block, ST-segment depression, or T-wave inversion were regarded as having an abnormal ECG.

Definition of the index diagnosis

Index events were classified by independent investigators with access to all clinical and laboratory data but unaware of the patients’ clinical outcome. Acute MI was diagnosed in accordance with the ESC/ACC consensus document, using cTnI elevation ≥0.1 µg/L in at least two measurements within 24 h from admission as the biochemical criterion.14

Follow-up

After discharge, patients were followed by research nurses with telephone contacts at 30 days and at 6 (±1) months. Information regarding death was obtained from the Swedish National Registry on Mortality, information regarding (recurrent) MI from the hospitals’ diagnosis registry and patient records. No patient was lost to follow-up.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are reported as medians (interquartile range); comparisons were performed by the Mann–Whitney U test or the Kruskal–Wallis test, as appropriate. Categorical variables are expressed as numbers and percentages, differences were analysed using Pearson’s χ2 test. To evaluate the relationships between continuous variables, Spearman's rank-correlation coefficients were calculated. To evaluate the associations between GDF-15 levels and clinical baseline variables (age, gender, hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidaemia, previous or current smoking, history of coronary revascularization, previous MI, heart failure, abnormal admission ECG) and biomarker results [peak levels of cTnI ≥0.1 µg/L within 2 h (cTnI0–2 h), NT-proBNP, C-reactive protein, and cystatin C], multiple linear regression analysis was used. Because of the significant proportion of patients with undetectable levels of cTnI, this marker was entered into the analysis as a dichotomized variable on the basis of cTnI0–2 h < or ≥0.1 µg/L. The other biomarkers were entered as continuous variables, in case of NT-proBNP, C-reactive protein, and GDF-15 after ln transformation due to highly skewed levels.

The study endpoints were total mortality and (recurrent) MI, alone or in combination. To compare the prognostic information provided by different biochemical markers, receiver operator characteristic (ROC) curves were generated. Differences between the areas under the ROC curves were assessed using the Wilcoxon one-sample test. The prognostic importance of GDF-15 and the clinical risk indicators and biochemical markers included in the multiple linear regression analysis was assessed by logistic regression analysis using univariable and multivariable models. The multivariable model included all tested variables. In addition, the prognostic value of the pre-specified GDF-15 cut-off levels of 1200 ng/L and 1800 ng/L was tested alone and in combination with peak cTnI0–2 h or an abnormal ECG on admission. All P-values reported are from two-sided tests and regarded as statistically significant if <0.05. No adjustments for multiplicity were made as the results are to be considered exploratory. All data analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences 12.0.1 and 14.0 software programs (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Patient characteristics

The combined patient cohort consisted of 479 patients (65% males) with a median (inter-quartile range) age of 66 (57–75) years. The median time from symptom onset to admission and first blood sample was 4.9 (3.4–6.9) h. The index event was classified as an acute MI in 144 patients (30%), unstable angina in 84 patients (18%), other cardiac disease in 52 patients (11%), non-cardiac disease in 31 patients (6%), and unspecified chest pain in 168 patients (35%). The group with other cardiac disease included patients with stable angina, arrhythmias, or manifestations of chronic heart failure, the group with non-cardiac disease included patients with gastrointestinal disorders, pulmonary, or aortic disease. Baseline characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics

| FAST II (n = 169) | FASTER I (n = 310) | Combined (n = 479) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Age (years) | 67 (58–75) | 65 (57–76) | 66 (57–75) |

| Male gender | 112 (66) | 200 (65) | 312 (65) |

| Cardiovascular risk factors | |||

| Hypertension | 80 (47) | 119 (38) | 199 (42) |

| Diabetes | 27 (16) | 53 (17) | 80 (17) |

| Hyperlipidaemia | 47 (28) | 123 (40) | 170 (35) |

| Previous or current smoking | 101 (60) | 186 (60) | 287 (60) |

| Previous cardiovascular disease | |||

| Angina pectoris >1 month | 77 (46) | 124 (40) | 201 (42) |

| Previous revascularization | 50 (30) | 89 (29) | 139 (29) |

| Previous MI | 65 (38) | 97 (31) | 162 (34) |

| Heart failure | 31 (18) | 47 (15) | 78 (16) |

| ECG on admission | |||

| ST-segment depression | 22 (16) | 54 (21) | 76 (19) |

| T-wave inversion | 42 (30) | 46 (18) | 88 (22) |

| LBBB | 9 (5) | 12 (4) | 21 (4) |

| Q-wave | 22 (13) | 37 (12) | 59 (12) |

| Any abnormal ECG | 93 (55) | 149 (48) | 242 (51) |

| Biomarker levels | |||

| cTnI ≥0.1 µg/L within 2 h | 59 (35) | 102 (33) | 161 (34) |

| NT-proBNP (ng/L) | 222 (86–836) | 174 (62–655) | 190 (75–740) |

| C-reactive protein (mg/L) | 1.87 (0.91–4.65) | 2.35 (1.29–5.62) | 2.09 (0.98–4.93) |

| Cystatin C (mg/L) | 1.07 (0.94–1.27) | 1.18 (1.08–1.33) | 1.15 (1.03–1.32) |

| Index diagnosis | |||

| Acute MI | 44 (26) | 100 (32) | 144 (30) |

| Unstable angina | 21 (12) | 63 (20) | 84 (18) |

| Other cardiac disease | 40 (24) | 12 (4) | 52 (11) |

| Non-cardiac disease | 17 (10) | 14 (5) | 31 (6) |

| Unspecified chest pain | 47 (28) | 121 (39) | 168 (35) |

Data are presented as absolute number (percentage) or median (inter-quartile range). Analysis of ST-segment changes was based on 402 patients without confounding ECG findings, i.e. left bundle branch block (LBBB) or pacing.

Growth-differentiation factor-15 levels on admission in relation to baseline variables

The concentration of GDF-15 on admission ranged from 50 to 24 850 ng/L, with a median (inter-quartile range) of 1496 (1101–2279) ng/L. One hundred and forty-nine patients (31%) presented with a GDF-15 level within the normal range (<1200 ng/L). GDF-15 levels were moderately elevated (between 1200 and 1800 ng/L) in 156 patients (33%) and highly elevated (>1800 ng/L) in 174 patients (36%). Patients with elevated levels of GDF-15 tended to be older and were more likely to have hypertension or diabetes, to have a history of tobacco use or cardiovascular disease, or to present with an abnormal ECG (Table 2). Patients with elevated levels of GDF-15 were also more likely to develop a peak cTnI0–2 h level ≥0.1 µg/L or to present with increased levels of NT-proBNP, C-reactive protein, or cystatin C (Table 2). The relation of GDF-15 to these four biomarkers was further illustrated by linear correlation analysis, showing that GDF-15 levels were strongly related to cystatin C (r = 0.59; P < 0.001) and NT-proBNP (r = 0.58; P < 0.001) and weakly related to C-reactive protein (r = 0.27; P < 0.001) and peak cTnI0–2 h (r = 0.22; P < 0.001).

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics according to growth-differentiation factor-15 levels on admission

| GDF-15 <1200 ng/L (n = 149) | GDF-15 1200–1800 ng/L (n = 156) | GDF-15 >1800 ng/L (n = 174) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||

| Age (years) | 56 (50–63) | 67 (60–74) | 75 (65–80) | <0.001 |

| Male gender | 92 (62) | 102 (65) | 118 (68) | 0.52 |

| Delay time (h) | 4.8 (3.6–6.8) | 5.1 (3.5–6.6) | 4.8 (3.1–6.9) | 0.61 |

| Cardiovascular risk factors | ||||

| Hypertension | 47 (32) | 59 (38) | 93 (53) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes | 9 (6) | 20 (13) | 51 (29) | <0.001 |

| Hyperlipidaemia | 46 (31) | 50 (32) | 74 (43) | 0.05 |

| Previous or current smoking | 72 (48) | 103 (66) | 112 (64) | 0.002 |

| Previous cardiovascular disease | ||||

| Angina pectoris >1 month | 39 (26) | 57 (37) | 105 (60) | <0.001 |

| Previous revascularization | 32 (22) | 38 (24) | 69 (40) | <0.001 |

| Previous MI | 32 (21) | 41 (26) | 89 (51) | <0.001 |

| Heart failure | 5 (3) | 17 (11) | 56 (32) | <0.001 |

| ECG on admission | ||||

| ST-segment depression | 12 (9) | 24 (18) | 40 (32) | <0.001 |

| T-wave inversion | 19 (14) | 36 (26) | 33 (26) | 0.01 |

| LBBB | 3 (2) | 2 (1) | 16 (9) | 0.001 |

| Q-wave | 11 (7) | 19 (12) | 29 (17) | 0.04 |

| Any abnormal ECG | 44 (30) | 76 (49) | 122 (70) | <0.001 |

| Biomarker levels | ||||

| cTnI ≥0.1 µg/L within 2 h | 32 (21) | 59 (38) | 70 (40) | 0.001 |

| NT-proBNP (ng/L) | 74 (29–165) | 177 (99–493) | 728 (199–1871) | <0.001 |

| C-reactive protein (mg/L) | 1.47 (0.79–3.10) | 2.00 (1.01–4.04) | 3.25 (1.33–9.19) | <0.001 |

| Cystatin C (mg/L) | 1.04 (0.95–1.12) | 1.16 (1.06–1.26) | 1.36 (1.16–1.59) | <0.001 |

Data are presented as absolute number (percentage) or median (inter-quartile range). Analysis of ST-segment changes was based on 402 patients without confounding ECG findings, i.e. left bundle branch block (LBBB) or pacing. Delay time refers to the time from symptom onset to first blood sample.

By multiple linear regression analysis using ln GDF-15 as the dependent variable, age, male gender, diabetes, a history of smoking, and the levels of NT-proBNP, C-reactive protein, and cystatin C were significantly related to GDF-15 (Table 3). The R2 value of this model was 0.60.

Table 3.

Clinical and biochemical variables associated with growth-differentiation factor-15

| Characteristics | B (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| Age (per 10 years) | 0.12 (0.09–0.16) | <0.001 |

| Male gender | 0.11 (0.04–0.19) | 0.002 |

| Hypertension | 0.01 (−0.06 to 0.09) | 0.73 |

| Diabetes | 0.36 (0.26–0.46) | <0.001 |

| Hyperlipidaemia | 0.03 (−0.06 to 0.12) | 0.49 |

| Previous or current smoking | 0.10 (0.03–0.17) | 0.005 |

| Previous revascularization | −0.07 (−0.17 to 0.03) | 0.15 |

| Previous MI | 0.04 (−0.05 to 0.13) | 0.36 |

| Previous heart failure | 0.06 (−0.05 to 0.16) | 0.28 |

| Any abnormal ECG | −0.04 (−0.11 to 0.04) | 0.37 |

| cTnI ≥0.1 µg/L within 2 h | −0.07 (−0.14 to 0.01) | 0.08 |

| ln NT-proBNP | 0.08 (0.05–0.11) | <0.001 |

| ln C-reactive protein | 0.06 (0.03–0.09) | <0.001 |

| Cystatin C | 0.65 (0.52–0.76) | <0.001 |

| Trial (FAST II vs. FASTER I) | 0.03 (−0.04 to 0.10) | 0.41 |

Multiple linear regression analysis. Association with ln GDF-15 is shown. CI denotes confidence interval.

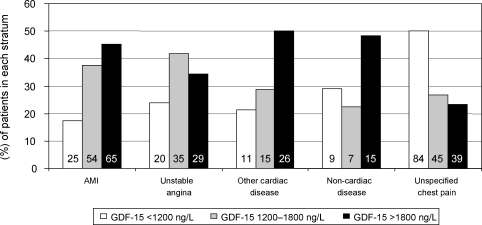

Growth-differentiation factor-15 levels on admission in relation to diagnosis

The median (inter-quartile range) GDF-15 level in patients with a final diagnosis of acute MI was 1701 (1312–2684) ng/L, 1452 (1208–2218) ng/L in patients with unstable angina, 1805 (1307–2591) ng/L in patients with other cardiac disease, and 1628 (1157–2366) ng/L in patients with non-cardiac disease. The median GDF-15 level in patients with unspecified chest pain was 1207 (891–1737) ng/L, which was significantly lower when compared with patients with other index diagnoses (P < 0.005). Patients with unspecified chest pain were significantly younger, had less-established cardiovascular disease, and had lower levels of NT-proBNP, C-reactive protein, and cystatin C when compared with the other diagnostic subgroups (data not shown). Distribution of GDF-15 levels according to index diagnosis and the pre-specified cut-off values of 1200 and 1800 ng/L is shown in Figure 1. Among patients with a final diagnosis of acute MI, 83% presented with elevated levels of GDF-15 (≥1200 ng/L); the respective numbers were 76, 79, 71, and 50% in patients with unstable angina, other cardiac disease, non-cardiac disease, and unspecified chest pain, respectively.

Figure 1.

Levels of growth-differentiation factor-15 on admission in relation to index diagnosis. For each diagnosis, the percentages of patients with growth-differentiation factor-15 levels <1200 ng/L, between 1200 and 1800 ng/L, and >1800 ng/L are shown. Absolute patient numbers are shown in each bar.

Growth-differentiation factor-15 levels on admission in relation to outcome

After 6 months, 13 patients (2.7%) had died and 23 patients (4.8%) had suffered a (recurrent) MI. Overall, 32 patients (6.7%) had reached the composite endpoint of death or (recurrent) MI. The risk of the composite endpoint was 14.6% (21 out of 144 patients) among patients with an index diagnosis of acute MI, 6.0% (five out of 84) among patients with unstable angina, 7.7% (four out of 52) among patients with other cardiac disease, and 6.5% (2 out of 31) among patients with non-cardiac disease. No patient with unspecified chest pain reached the composite endpoint.

There was a graded relationship between the levels of GDF-15 on admission and the risk of death and/or (recurrent) MI during follow-up (Figure 2A). No deaths occurred among patients with GDF-15 levels <1200 ng/L, whereas two patients (1.3%) with GDF-15 levels between 1200 and 1800 ng/L and 11 patients (6.3%) with GDF-15 levels >1800 ng/L died (P = 0.001). Likewise, two (1.3%), seven (4.5%), and 14 (8.0%) patients had a (recurrent) MI (P = 0.019), and two (1.3%), eight (5.1%) and 22 (12.6%) patients reached the composite endpoint in the three strata of GDF-15 (P < 0.001). The timing of events for the composite endpoint in shown in Figure 2B. Patients who reached the composite endpoint had significantly higher median (inter-quartile range) levels of GDF-15 on admission [2904 (1701–4159) ng/L] when compared with patients without an event [1462 (1077–2083) ng/L; P < 0.001]. GDF-15 levels were also significantly higher in patients who died during follow-up [4139 (2663–5088) ng/L] when compared with patients who survived [1479 (1090–2191) ng/L; P < 0.001] and in patients who had a (recurrent) MI [2583 (1614–3468) ng/L] when compared with patients without such event [1476 (1084–2205) ng/L; P = 0.001].

Figure 2.

Outcome according to levels of growth-differentiation factor-15 on admission. (A) The risks of death, (recurrent) MI, and of the composite endpoint after 6 months are shown. The number of events is shown in each bar. (B) The Kaplan–Meier curve illustrating the timing of events for the composite endpoint in the three strata of growth-differentiation factor-15. (Re)-MI denotes (recurrent) myocardial infarction.

Growth-differentiation factor-15 in the context of other markers of adverse prognosis

By univariable logistic regression analysis, age, a history of previous MI, abnormal ECG findings, a peak cTnI0–2 h level ≥0.1 µg/L, and the levels of NT-proBNP, C-reactive protein, cystatin C, and GDF-15 were all related to the risk of the composite endpoint after 6 months (Table 4). ROC curve analysis further illustrated that GDF-15 is a strong biochemical indicator of the composite endpoint with a c-statistic of 0.78 (optimal cut-off, 2170 ng/L), when compared with cystatin C (c-statistic, 0.76), NT-proBNP (c-statistic, 0.75), peak cTnI0–2 h (c-statistic, 0.73), and C-reactive protein (c-statistic, 0.61).

Table 4.

Logistic regression analyses for the composite endpoint at 6 months in relation to risk markers at presentation

| Univariable model |

Multivariable model |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | OR (95% CI) | P-value | OR (95% CI) | P-value |

| Age (per 10 years) | 2.2 (1.5–3.2) | <0.001 | 1.1 (0.7–1.7) | 0.82 |

| Male gender | 1.4 (0.6–3.1) | 0.40 | 1.0 (0.4–2.7) | 0.96 |

| Hypertension | 1.3 (0.6–2.6) | 0.54 | 1.0 (0.4–2.5) | 0.94 |

| Diabetes | 1.4 (0.6–3.6) | 0.46 | 0.7 (0.2–2.0) | 0.46 |

| Hyperlipidaemia | 0.6 (0.3–1.3) | 0.21 | 0.4 (0.1–1.3) | 0.12 |

| Previous or current smoking | 0.7 (0.4–1.5) | 0.41 | 0.6 (0.2–1.3) | 0.17 |

| Previous revascularization | 1.3 (0.6–2.8) | 0.49 | 1.5 (0.5–4.5) | 0.44 |

| Previous MI | 2.7 (1.3–5.6) | 0.007 | 2.1 (0.8–5.4) | 0.14 |

| Previous heart failure | 2.1 (0.9–4.8) | 0.07 | 0.6 (0.2–1.8) | 0.39 |

| Any abnormal ECG | 3.1 (1.4–7.0) | 0.007 | 1.2 (0.4–3.2) | 0.77 |

| cTnI ≥0.1 µg/L within 2 h | 5.7 (2.5–12.5) | <0.001 | 4.7 (1.8–12.0) | 0.001 |

| ln NT-proBNP | 1.8 (1.4–2.3) | <0.001 | 1.0 (0.7–1.5) | 0.84 |

| ln C-reactive protein | 1.4 (1.1–1.8) | 0.013 | 1.2 (0.9–1.7) | 0.29 |

| Cystatin C | 9.0 (3.4–23.6) | <0.001 | 2.7 (0.7–10.4) | 0.16 |

| ln GDF-15 | 4.5 (2.5–8.1) | <0.001 | 2.7 (1.0–6.0) | 0.046 |

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval. The multivariable model was adjusted for all variables in the univariable model and for trial (FAST II vs. FASTER I).

By multivariable analysis, a peak cTnI0–2 h level ≥0.1 µg/L [odds ratio (OR), 4.7; 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.8–12.0; P = 0.001) and GDF-15 (OR, 2.7; 95% CI 1.0–6.9; P = 0.046) emerged as the only independent predictors of the composite endpoint (Table 4). Removing cystatin C from the model improved the predictive value of GDF-15 (OR, 3.6; 95% CI 1.5–8.4; P = 0.003), whereas the prognostic value of cTnI0–2 h ≥0.1 µg/L remained unchanged (OR 4.5; 95% CI 1.8–11.4; P = 0.002).

A single value of GDF-15 within the normal range (<1200 ng/L) on admission performed better in identifying low-risk patients, than a peak cTnI0–2 h level <0.1 µg/L: among patients with a normal GDF-15 level, 1.3% (two out of 149) reached the composite endpoint after 6 months, whereas 2.9% (nine out of 312) of the patients with a peak cTnI0–2 h level <0.1 µg/L did (P = 0.039).

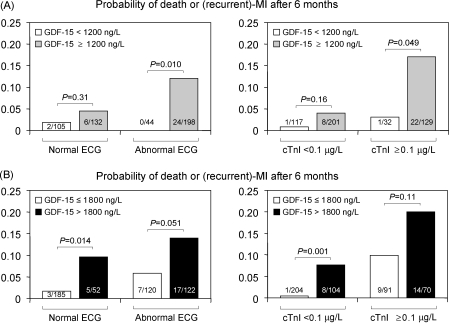

Growth-differentiation factor-15 adds prognostic information to the ECG and cardiac troponin I

GDF-15 levels determined on admission added significant prognostic information to ECG findings on admission and peak cTnI0–2 h levels. This was reflected by an increase in the c-statistic for the composite endpoint from 0.74 (95% CI 0.65–0.83) for the combination of peak cTnI0–2 h and the ECG to 0.83 (95% CI 0.76–0.90) after addition of GDF-15 (P < 0.001). Among patients with an abnormal ECG or with peak cTnI0–2 h levels ≥0.1 µg/L, a GDF-15 level within the normal range (<1200 ng/L) identified individuals at very low risk of adverse events: none out of 44 patients with an abnormal ECG but a normal GDF-15 value reached the composite endpoint after 6 months; similarly, there was only one event among 32 patients with a peak cTnI0–2 h level ≥0.1 µg/L and normal GDF-15 value (Figure 3A). Conversely, in patients with peak cTnI0–2 h levels <0.1 µg/L or a normal ECG, a GDF-15 level >1800 ng/L offered incremental prognostic information and identified individuals at high risk of the composite endpoint (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Outcome according to the ECG, peak cTnI levels within 2 h, and growth-differentiation factor-15. Patients were stratified according to the presence or absence of an abnormal ECG on admission or according to their peak cTnI0–2 h level (cTnI). Patients were then classified according to their levels of growth-differentiation factor-15 on admission using the pre-specified cut-offs, 1200 ng/L (A) and 1800 ng/L (B). The number of events per number of patients is shown in each bar.

Discussion

This study shows that the level of GDF-15, as measured in the first blood sample on admission, provides independent prognostic information on the risk of death or (recurrent) MI in a heterogeneous patient population with acute chest pain. Patients with a GDF-15 level within the normal range (<1200 ng/L) had a very good prognosis with a 6-month risk of the composite endpoint of 1.3% without any deaths. Conversely, the prognosis was significantly impaired at higher GDF-15 levels, with rates of the composite endpoint of 5.1 and 12.6% in patients with moderately elevated (between 1200 and 1800 ng/L) or markedly elevated (>1800 ng/L) levels of GDF-15, respectively.

Currently, serial analyses of the ECG and troponin testing are the recommended procedures for triage and early risk stratification in patients with chest pain suggestive of an acute coronary syndrome.1,2 The presence of an abnormal ECG or elevated levels of troponin is associated with an increased risk of adverse cardiac events in patients with confirmed non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndrome,15–17 and in more unselected chest pain populations.3–5 However, in unselected populations, a significant proportion of patients with a final diagnosis of non-cardiac disease, or even unspecified chest pain, may have elevated levels of cTnI.18 Moreover, some patients with acute chest pain and elevated levels of cTnI do not have blood flow-limiting coronary artery disease,5 highlighting the need for additional markers to identify individuals at high risk of adverse cardiac events among the heterogeneous group of troponin-positive patients.

GDF-15, measured on admission, added prognostic information to the ECG and to cTnI measured serially during the first 2 h from admission. A GDF-15 level <1200 ng/L identified low-risk subjects among the patient cohorts with an abnormal ECG or elevated cTnI. In contrast, a GDF-15 level >1800 ng/L was useful for the identification of high-risk individuals among the cohorts with a normal ECG or without elevated cTnI, which are usually regarded as low-risk. Given the complexity of cardiac risk modelling, these results have to be regarded as explorative. Although our data indicate that 1200 and 1800 ng/L are useful cut-points for risk stratification, this does not imply that risk is homogeneous within each of these strata.

It has been shown that a multimarker strategy combining the ECG and markers of myocyte necrosis with markers of renal dysfunction, inflammation, or natriuretic peptides may provide additional insight into pathophysiological mechanisms and enhance risk stratification in patients with chest pain and unstable coronary artery disease.19–21 Elevated levels of NT-proBNP, C-reactive protein, cystatin C, and GDF-15 were all related to a higher risk of adverse outcomes in the present study. Among these biomarkers, only GDF-15 provided independent prognostic information besides cTnI in our patient population. It thus appears that GDF-15 could provide incremental prognostic information even to more complex risk prediction models. This, however, remains to be validated prospectively.

Patients presenting with elevated GDF-15 levels were characterized by high-risk features such as increased age and a higher prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors and previous cardiovascular disease. In accordance with previous experiences,8,9,22 age, male gender, diabetes, smoking, ventricular wall stress and ischaemia (NT-proBNP), inflammation (C-reactive protein), and renal dysfunction (cystatin C) were independently associated with elevated GDF-15 levels. Thus, an elevated level of GDF-15 seems to reflect several underlying conditions, acute and/or chronic, associated with adverse cardiovascular outcomes. In particular, renal dysfunction appeared to mediate part of the prognostic impact of GDF-15 given the close correlation between levels of GDF-15 and cystatin C and considering the results of the multivariable analysis. However, the aforementioned factors explained only part of the variation in the GDF-15 levels, indicating that additional, as yet undefined factors contribute to the concentration of GDF-15. GDF-15 is highly expressed in the infarcted myocardium in patients with an acute MI,6 and also in atherosclerotic plaques obtained from patients undergoing carotid artery surgery.23 It will be important to further elucidate the factors regulating the expression GDF-15 in the myocardium and in the vessel wall to improve the understanding of the pathobiology of this new biomarker.

Patients with unspecified chest pain presented with significantly lower GDF-15 levels when compared with the other diagnostic subgroups, which seems related to the fact that these individuals were younger and had less-established cardiovascular disease and no acute cardiac condition. Otherwise, there was a considerable overlap in the GDF-15 levels in patients with different chest pain aetiologies. As previously shown, circulating levels of GDF-15 are elevated and provide independent prognostic information in patients with unstable angina and non-ST-elevation MI,8 ST-elevation MI,24 chronic ischaemic and non-ischaemic heart failure,22 and acute pulmonary embolism,25 indicating that elevated GDF-15 levels identify high-risk individuals across a broad spectrum of cardiovascular disease. Conversely, GDF-15 levels <1200 ng/L have been found to be associated with favourable outcomes in all of these conditions. Accordingly, the role of GDF-15 in the differential diagnostic work-up of patients with acute chest pain may be limited. Instead, GDF-15 may be useful for risk stratification at initial presentation across the heterogeneous spectrum of patients with acute chest pain.

In conclusion, GDF-15 is a strong and independent biomarker of adverse outcome in patients with acute chest pain. GDF-15 provides prognostic information beyond conventional risk markers, such as the ECG and serial cTnI measurements. Recent data suggest that patients with non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndrome presenting with an elevated GDF-15 level benefit from early revascularization, whereas patients with a normal GDF-15 level do not, regardless of their troponin levels.9 Accordingly, GDF-15 may be valuable for early triage and therapeutic decision-making. The impact on resource utilization, health-care costs, and patient outcome of a management strategy that incorporates GDF-15 should be explored in a prospective clinical trial.

Funding

Funding for the study and to pay the Open Access publication charges for this article was provided by BioChancePlus (German Ministry of Education and Research).

Acknowledgement

We gratefully acknowledge the expertise of Karin Jensevik, Sylvia Olofsson and Lars Berglund for statistical advice.

Conflict of interest: K.C.W., T.K., and L.W. have filed a patent and have a contract with Roche Diagnostics to develop a GDF-15 assay for cardiovascular applications.

References

- 1.Bassand JP, Hamm CW, Ardissino D, Boersma E, Budaj A, Fernandez-Aviles F, Fox KA, Hasdai D, Ohman EM, Wallentin L, Wijns W, Vahanian A, Camm J, De Caterina R, Dean V, Dickstein K, Filippatos G, Kristensen SD, Widimsky P, McGregor K, Sechtem U, Tendera M, Hellemans I, Gomez JL, Silber S, Funck-Brentano C, Andreotti F, Benzer W, Bertrand M, Betriu A, DeSutter J, Falk V, Ortiz AF, Gitt A, Hasin Y, Huber K, Kornowski R, Lopez-Sendon J, Morais J, Nordrehaug JE, Steg PG, Thygesen K, Tubaro M, Turpie AG, Verheugt F, Windecker S. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes. The Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Non-ST-Segment Elevation Acute Coronary Syndromes of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J. 2007;28:1598–1660. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson JL, Adams CD, Antman EM, Bridges CR, Califf RM, Casey DEJ, Chavey WEn, Fesmire FM, Hochman JS, Levin TN, Lincoff AM, Peterson ED, Theroux P, Wenger NK, Wright RS. ACC/AHA 2007 guidelines for the management of patients with unstable angina/non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the 2002 Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Unstable Angina/Non-ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction): developed in collaboration with the American College of Emergency Physicians, American College of Physicians, Society for Academic Emergency Medicine, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and Society of Thoracic Surgeons. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:e1–e157. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heeschen C, Goldmann BU, Langenbrink L, Matschuck G, Hamm CW. Evaluation of a rapid whole blood ELISA for quantification of troponin I in patients with acute chest pain. Clin Chem. 1999;45:1789–1796. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jernberg T, Lindahl B. A combination of troponin T and 12-lead electrocardiography: a valuable tool for early prediction of long-term mortality in patients with chest pain without ST-segment elevation. Am Heart J. 2002;144:804–810. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2002.126116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kontos MC, Shah R, Fritz LM, Anderson FP, Tatum JL, Ornato JP, Jesse RL. Implication of different cardiac troponin I levels for clinical outcomes and prognosis of acute chest pain patients. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:958–965. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.10.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kempf T, Eden M, Strelau J, Naguib M, Willenbockel C, Tongers J, Heineke J, Kotlarz D, Xu J, Molkentin JD, Niessen HW, Drexler H, Wollert KC. The transforming growth factor-beta superfamily member growth-differentiation factor-15 protects the heart from ischemia/reperfusion injury. Circ Res. 2006;98:351–360. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000202805.73038.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xu J, Kimball TR, Lorenz JN, Brown DA, Bauskin AR, Klevitsky R, Hewett TE, Breit SN, Molkentin JD. GDF15/MIC-1 functions as a protective and antihypertrophic factor released from the myocardium in association with SMAD protein activation. Circ Res. 2006;98:342–350. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000202804.84885.d0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wollert KC, Kempf T, Peter T, Olofsson S, James S, Johnston N, Lindahl B, Horn-Wichmann R, Brabant G, Simoons ML, Armstrong PW, Califf RM, Drexler H, Wallentin L. Prognostic value of growth-differentiation factor-15 in patients with non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome. Circulation. 2007;115:962–971. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.650846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wollert KC, Kempf T, Lagerqvist B, Lindahl B, Olofsson S, Allhoff T, Peter T, Siegbahn A, Venge P, Drexler H, Wallentin L. Growth-differentiation factor-15 for risk stratification and selection of an invasive treatment strategy in non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndrome. Circulation. 2007;116:1540–1548. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.697714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eggers KM, Oldgren J, Nordenskjold A, Lindahl B. Diagnostic value of serial measurement of cardiac markers in patients with chest pain: limited value of adding myoglobin to troponin I for exclusion of myocardial infarction. Am Heart J. 2004;148:574–581. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2004.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eggers KM, Ellenius J, Dellborg M, Groth T, Oldgren J, Swahn E, Lindahl B. Artificial neural network algorithms for early diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction and prediction of infarct size in chest pain patients. Int J Cardiol. 2007;114:366–374. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2005.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kempf T, Horn-Wichmann R, Brabant G, Peter T, Allhoff T, Klein G, Drexler H, Johnston N, Wallentin L, Wollert KC. Circulating concentrations of growth-differentiation factor 15 in apparently healthy elderly individuals and patients with chronic heart failure as assessed by a new immunoradiometric sandwich assay. Clin Chem. 2007;53:284–291. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2006.076828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Panteghini M, Pagani F, Yeo KT, Apple FS, Christenson RH, Dati F, Mair J, Ravkilde J, Wu AH. Evaluation of imprecision for cardiac troponin assays at low-range concentrations. Clin Chem. 2004;50:327–332. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2003.026815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alpert JS, Thygesen K, Antman E, Bassand JP. Myocardial infarction redefined - a consensus document of The Joint European Society of Cardiology/American College of Cardiology Committee for the redefinition of myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;36:959–969. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(00)00804-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lindahl B, Toss H, Siegbahn A, Venge P, Wallentin L. Markers of myocardial damage and inflammation in relation to long-term mortality in unstable coronary artery disease. FRISC Study Group. Fragmin during Instability in Coronary Artery Disease. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1139–1147. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200010193431602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.James S, Armstrong P, Califf R, Simoons ML, Venge P, Wallentin L, Lindahl B. Troponin T levels and risk of 30-day outcomes in patients with the acute coronary syndrome: prospective verification in the GUSTO-IV trial. Am J Med. 2003;115:178–184. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(03)00348-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Westerhout CM, Fu Y, Lauer MS, James S, Armstrong PW, Al-Hattab E, Califf RM, Simoons ML, Wallentin L, Boersma E. Short- and long-term risk stratification in acute coronary syndromes: the added value of quantitative ST-segment depression and multiple biomarkers. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48:939–947. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.04.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eggers KM, Oldgren J, Nordenskjold A, Lindahl B. Risk prediction in patients with chest pain: early assessment by the combination of troponin I results and electrocardiographic findings. Coron Artery Dis. 2005;16:181–189. doi: 10.1097/00019501-200505000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sabatine MS, Morrow DA, de Lemos JA, Gibson CM, Murphy SA, Rifai N, McCabe C, Antman EM, Cannon CP, Braunwald E. Multimarker approach to risk stratification in non-ST elevation acute coronary syndromes: simultaneous assessment of troponin I, C-reactive protein, and B-type natriuretic peptide. Circulation. 2002;105:1760–1763. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000015464.18023.0a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jernberg T, Stridsberg M, Venge P, Lindahl B. N-terminal pro brain natriuretic peptide on admission for early risk stratification of patients with chest pain and no ST-segment elevation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;40:437–445. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)01986-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.James SK, Lindahl B, Siegbahn A, Stridsberg M, Venge P, Armstrong P, Barnathan ES, Califf R, Topol EJ, Simoons ML, Wallentin L. N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide and other risk markers for the separate prediction of mortality and subsequent myocardial infarction in patients with unstable coronary artery disease: a Global Utilization of Strategies to Open occluded arteries (GUSTO)-IV substudy. Circulation. 2003;108:275–281. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000079170.10579.DC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kempf T, von Haehling S, Peter T, Allhoff T, Cicoira M, Doehner W, Ponikowski P, Filippatos GS, Rozentryt P, Drexler H, Anker SD, Wollert KC. Prognostic utility of growth differentiation factor-15 in patients with chronic heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:1054–1060. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.04.091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schlittenhardt D, Schober A, Strelau J, Bonaterra GA, Schmiedt W, Unsicker K, Metz J, Kinscherf R. Involvement of growth differentiation factor-15/macrophage inhibitory cytokine-1 (GDF-15/MIC-1) in oxLDL-induced apoptosis of human macrophages in vitro and in arteriosclerotic lesions. Cell Tissue Res. 2004;318:325–333. doi: 10.1007/s00441-004-0986-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kempf T, Björklund E, Olofsson S, Lindahl B, Allhoff T, Peter T, Tongers J, Wollert KC, Wallentin L. Growth-differentiation factor-15 improves risk stratification in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J. 2007;28:2858–2865. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lankeit M, Kempf T, Dellas C, Cuny M, Tapken H, Peter T, Olschewski M, Konstantinides S, Wollert KC. Growth differentiation factor-15 for prognostic assessment of patients with acute pulmonary embolism. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;177:1018–1025. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200712-1786OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]