Abstract

The tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC)–mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway is a key regulator of cellular metabolism. We used conditional deletion of Tsc1 to address how quiescence is associated with the function of hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs). We demonstrate that Tsc1 deletion in the HSCs drives them from quiescence into rapid cycling, with increased mitochondrial biogenesis and elevated levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS). Importantly, this deletion dramatically reduced both hematopoiesis and self-renewal of HSCs, as revealed by serial and competitive bone marrow transplantation. In vivo treatment with an ROS antagonist restored HSC numbers and functions. These data demonstrated that the TSC–mTOR pathway maintains the quiescence and function of HSCs by repressing ROS production. The detrimental effect of up-regulated ROS in metabolically active HSCs may explain the well-documented association between quiescence and the “stemness” of HSCs.

A long-standing but poorly understood observation in stem cell biology is that the quiescence of the adult stem cells associates with their long-term functions (1–6). The molecular pathway that keeps them in quiescence is largely obscure, although recent studies have implicated stem cell niches (4) and cell-intrinsic functions of p21 (5) and Pten (6) in this process. The significance of quiescence in stem cell function is bolstered as genetic disruption of its quiescence almost invariably inactivates the hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) function (4–6). Nevertheless, it is largely unclear how an active metabolism is incompatible with a normal HSC function.

In addition to cell-intrinsic factors, accumulating data demonstrated that residence of adult HSCs in the BM niches is essential for their quiescence and long-term functions (7–9). Because exposure to high levels of oxygen damages the functions of HSCs (10–15), it has been proposed that hypoxia is important for HSC functions. However, the underlying molecular mechanism of how hypoxia maintains the stemness is unknown.

In Drosophila and in vitro–cultured mammalian cells, hypoxia activates tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC), which can inhibit the target of rapamycin (TOR), through REDD1 and AMP-activated protein kinase (16–20). Whether this pathway operates in the HSCs has yet to be tested.

The mammalian TOR (mTOR) pathway has emerged as a key regulator for cellular metabolism. Accumulating data have demonstrated that mTOR regulates several important cellular functions, including protein synthesis, autophagy, endocytosis and nutrient uptake (21). An increased mTOR activity results in increased cellular growth and nonmalignant growth of cells in solid organs (22, 23). Recently, it has been demonstrated that mTOR controls the mitochondrial oxidative function through a YY1–PGC-1α transcriptional complex (24). Although systemic analysis of the mTOR pathway in the function of HSCs has not been performed, several lines of evidence are consistent with a critical role for the pathway in HSC function. First, two groups reported that the targeted mutation of Pten, a negative regulator of phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) and AKT, which are inhibitors for TSC function, reduced long-term HSC (LT-HSC) function (6, 25). Second, up-regulated mTOR activity is associated with a higher level of intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) (26). Nevertheless, because these regulators have multiple functions, the link between the mTOR pathway and HSCs remains tentative.

TSC was first defined by genetic mutations leading to nonmalignant growth in solid organs in patients with genetic lesions of two genes, now called TSC1 and TSC2 (27, 28). Genetic screening in Drosophila demonstrated that the TSC determined the size of solid organs (29, 30). More recently, TSC has emerged as the major negative regulator for the mTOR (31, 32) (for review see reference 33).

In this paper, we demonstrate that the targeted mutation of TSC1 disrupts quiescence and long-term functions of the HSCs. Moreover, we showed that the Tsc1 defect leads to increased mitochondrion biogenesis and accumulation of ROS, and that the HSC defects can be largely restored by blocking ROS activity in vivo. Collectively, our data demonstrated that the TSC–mTOR pathway controls quiescence and functions of HSCs by repressing ROS production.

RESULTS

TSC1 controls quiescence of HSCs

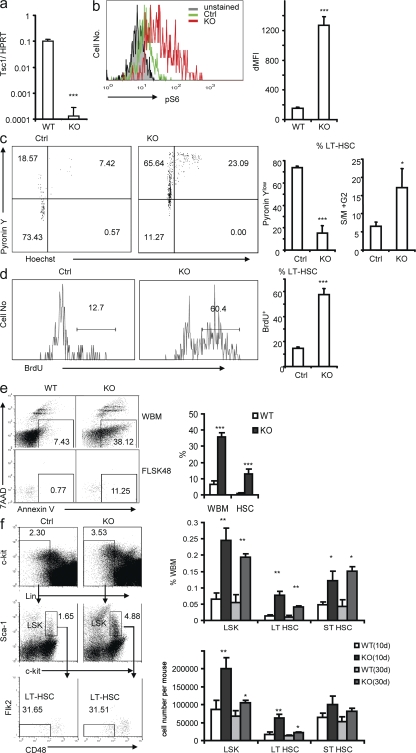

To address the function of mTOR activation in the biology of HSCs, we generated mice that express both MX-Cre and floxed Tsc1 locus and used polyinosine-polycytidine (pIpC) treatment to induce deletion of TSC in the HSCs. Starting at 6 wk of age, we treated the Tsc1fl/flmx-1-cre+ and the Tsc1fl/flmx-1-cre− (control [Ctrl]) mice with pIpC every other day for 2 wk to delete the Tsc1 gene, which is hereby referred to as KO in the figures. The pIpC treatment almost completely deleted the Tsc1 gene in the HSCs of the Tsc1fl/flmx-1-cre+ mice, as the Tsc1 transcripts in Flt2−Lin−Sca-1+c-Kit+ (FLSK) CD48− LT-HSCs (34) from Tsc1fl/flmx-1-cre+ mice were reduced by >500-fold at 10 d after the pIpC treatment (Fig. 1 a). In normal HSCs, mTOR activity is at a low level, as shown by flow cytometry of phosphorylated S6 (pS6), whereas in Tsc1 KO HSCs, the level of pS6 is increased by ∼10-fold (Fig. 1 b). These data confirmed that Tsc1 is completely deleted and mTOR activity is significantly increased in HSCs of Tsc1fl/flmx-1-cre+ mice after pIpC treatment.

Figure 1.

Loss of Tsc1 drives HSCs from quiescence to rapid proliferation and results in increased frequency and number of HSCs. (a) Tsc1 is efficiently deleted in LT-HSCs. The 6-wk-old Tsc1fl/flmx-1-cre+ mice and the Tsc1fl/flmx-1-cre− littermates were treated with pIpC for 2 wk. At 10 d after completion of pIpC treatments, LT-HSCs, as defined by the FLSKCD48− phenotype, were sorted by FACS. mRNA levels were tested by real-time RT-PCR. Data shown have been normalized to HPRT. Data shown are means ± SD of results from five independent experiments. (b) The pS6 level is up-regulated in Tsc1-deficient LT-HSCs measured by flow cytometry. The x axis shows the intensity of pS6 staining, and the y axis shows the cell number. (left) Representative FACS profiles. (right) Means ± SD (n = 3) of mean fluorescence. The mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) is increased by ∼10-fold in the Tsc1-deficient HSCs. (c) RNA/DNA contents of the Ctrl and Tsc1fl/flmx-1-cre+ HSCs. Tsc1fl/flmx-1-cre+ HSCs are less quiescent than the Tsc1fl/flmx-1-cre− littermates, as measured by pyronin Y (RNA contents) and HOECHST (DNA contents) staining. (left) Dot plots of gated FLSKCD48− cells are shown (numbers indicate percentages). (right) The summary data of quiescent (percentage of pyronin Ylow cells) and the percentage of S, M, and G2M cells (>2n DNA contents) are shown. Data shown are means ± SD of results from three independent experiments with a total of six mice per group. (d) Conditional deletion of the Tsc1 gene resulted in enhanced proliferation of the LT-HSCs. Mice were treated with pIpC as in panel a. BM cells were analyzed 24 h after BrdU labeling. (left) The histograms depict distributions of BrdU incorporation among the FLSKCD48− cells (numbers indicate percentages). (right) The bar graph shows the percentage of BrdU+ cells among the FLSKCD48− cells. Data shown are means ± SD of results from three independent experiments, with a total of six mice per group. (e) Tsc1-deficient WBM and HSCs have increased apoptosis, indicated as Annexin V+ 7AAD−. (left) Representative profiles from one mouse per group are presented (numbers indicate percentages). (right) Means ± SD of the percentage of Annexin V+7AAD− cells from four experiments with a total of eight mice per group are shown. (f) Sustained increase in the frequency and absolute number of HSCs in the pIpC-treated Tsc1fl/flmx-1-cre+ BM. At 10 and 30 d after pIpC treatments, BM from Tsc1fl/flmx-1-cre+ (KO) and Tsc1fl/flmx-1-cre− (Ctrl) littermates were stained with a panel of antibodies to identify LT-HSCs and short-term HSCs (ST-HSCs). (left) Data shown are FACS profiles depicting the increase in the frequency of HSCs on day 10 after completion of the pIpC treatment (numbers indicate percentages). (right) The bar graphs summarize the sustained increase in the frequency and number of HSCs on days 10 and 30 after pIpC treatment. Data shown are means ± SD of results from three (day 30; n = 6) or five (day 10; n = 10) experiments.

It is proposed that one of the major functions of the hypoxic HSC niche is to keep HSCs quiescent and that the quiescence is critical to maintain the stemness (14, 35). Therefore, we tested the effect of mTOR activation on stem cell quiescence. First, we measured the total RNA/DNA contents in the LT-HSCs by pyronin/HOECHST staining. As shown in Fig. 1 c, at 10 d after pIpC treatment ∼70% of the FLSKCD48− LT-HSCs in the Ctrl mice are pyronin Ylow, consistent with their quiescent status. In the pIpC-treated Tsc1fl/flmx-1-cre+ mice, only <15% of the LT-HSCs were pyronin Ylow, which indicated that most of the LT-HSCs had exited the G0 phase. Judged by DNA contents, a significant increase in the proportion of S- and G2M-phase cells was also observed.

Second, we measured the rate of HSC proliferation by BrdU incorporation, as shown in Fig. 1 d. At 10 d after pIpC treatment, nearly 60% of LT-HSCs in Tsc1fl/flmx-1-cre+ mice incorporated BrdU after 24 h of labeling, which is nearly fourfold as high as those from the Ctrl mice (13%). Thus, the data in Fig. 1 (a–d) indicated that Tsc1 deficiency drives HSCs from quiescence to rapid cell cycle.

By flow cytometry staining with Annexin V and 7–aminoactinomycin D, we observed that the levels of apoptosis among Ctrl HSCs is low (1%), as compared with that of the whole BM (WBM; 7%; Fig. 1 e). However, the apoptosis of Tsc1 KO HSCs was increased by >10-fold (Fig. 1 e). Overall, significant increases in both the frequency and number of HSCs were observed in the pIpC-treated Tsc1fl/flmx-1-cre+ mice (Fig. 1 f). Therefore, the increase in proliferation appeared to dominate over apoptosis. The increase of apoptosis may explain the reduction in the frequency and absolute number of HSCs in Tsc1fl/flmx-1-cre+ mice on day 30 when compared with those on day 10 (Fig. 1 f).

Targeted mutation of TSC1 causes HSC-intrinsic defects in hematopoiesis

Interestingly, despite the increase in HSC numbers, the pIpC-treated Tsc1fl/flmx-1-cre+ mice have an ∼50% reduction in white blood cell counts (P = 0.001) at 30 d after the pIpC treatment, as measured by a complete blood count (CBC) test, most of which are contributed by reduced lymphocytes. The counts of monocytes and RBCs in the mutant mice appeared normal (Fig. 2 a). To understand the hematopoiesis defects after the deletion of Tsc1, we analyzed a representation of multiple lineages of hematopoietic cells in the BM. We found that in Tsc1fl/flmx-1-cre+ mice, the BM cellularity is significantly reduced on day 10 of the pIpC treatments. The BM hypocellularity is more severe on day 30 (Fig. 2 b). Differentiated blood cells, such as B lymphocytes, myeloid cells, and erythroid cells, are also significantly reduced in the WBM compared with those in the Ctrl BM (Fig. 2 c).

Figure 2.

Conditional deletion of Tsc1 results in abnormal hematopoiesis. The 6-wk-old Tsc1fl/flmx-1-cre+ mice and the Tsc1fl/flmx-1-cre− littermates were treated with pIpC, as in Fig. 1. (a) Reduced number of blood cells, as determined by CBC. The number in the littermate Ctrl is defined as 100%. LY, lymphocytes; MO, monocytes; NE, neutrophils and eosinophils. (b) Progressive loss of BM cellularity in the Tsc1-deficient Tsc1fl/flmx-1-cre+ mice. (c) Reduction of multiple lineages of differentiated leukocytes in the BM at 30 d after pIpC treatments. (d) Reduction of B lymphocytes but increase of erythrocytes in the spleens of Tsc1 mutant mice at 30 d after pIpC treatments. (e) Deletion of the Tsc1 gene caused extramedullary hematopoiesis in the spleen. (left) The number of FLSK48− HSCs in the spleens of Tsc1fl/flmx-1-cre+ and Ctrl mice 10 and 30 d after pIpC treatment. Data shown in a–e are means ± SD of results from five experiments with a total of 10 mice per group. (middle) Hematoxylin and eosin staining of the spleens of Tsc1fl/flmx-1-cre+ and Ctrl littermates. The arrows indicate the high frequency of megakaryocytes. Bars, 20 μm. In five higher power fields, means of 49 and 7 megakaryocytes were found in spleen sections of Tsc1fl/flmx-1-cre+ and Ctrl littermates, respectively (n = 4). (f) Radioprotection by the Tsc1 mutant splenic HSCs. 20 × 106 spleen cells were injected into lethally irradiated recipients. The survival rates were compared by Kaplan-Meier analysis (n = 5).

The BM hypocellularity could in theory be caused by increased apoptosis and/or defective proliferation. To evaluate the rate of proliferation of WT and KO BM in vivo, we pulsed the WT and KO mice with BrdU on day 10 after pIpC treatment and measured BrdU incorporation on total and Lin− BM cells 24 h after the pulse. As shown in Fig. S1 (available at http://www.jem.org/cgi/content/full/jem.20081297/DC1), the rate of BrdU incorporation was similar in WT and KO BM, regardless of whether the WBM or Lin− cells were compared. To determine whether TSC1 deletion impaired the colony formation activity of progenitor cells, we compared the WT and KO BM for the number and types of colonies formed in a standard CFU assay. As shown in Table S1, an increase of total colonies, including that of granulocyte erythroid macrophage and megakaryocyte, and macrophage colonies was observed. The size of colonies from the KO BM was also actually somewhat larger (not depicted). In contrast, the percentage of cells undergoing apoptosis (Annexin V+7–aminoactinomycin D−) was increased by almost fivefold in the KO BM (Fig. 1 e). Therefore, the paradoxical BM hypocellularity in the KO mice is likely caused by apoptosis. In the spleen of Tsc1 mutant mice, the B lymphocytes are reduced to half of those in Ctrl mice, whereas the erythroid cells are dramatically increased (Fig. 2 d).

Interestingly, the numbers of megakaryocytes also increased (Fig. 2 e), which suggested extramedullary hematopoiesis. Consistent with this notion, a significant numbers of HSCs was found in the Tsc1-deficient spleen but not in Ctrl spleen. The increase in the number of spleen HSCs persisted on day 30 after pIpC treatment, although this was decreased compared with that on day 10 (Fig. 2 e). The HSCs in the Tsc1-deficient spleen rescued the lethally irradiated recipients for >9 mo (Fig. 2 f). However, because the HSCs have reduced self-renewal when their niche in BM is disrupted (36–38), it is unlikely that the HSCs in the spleen are fully functional. Furthermore, the KO splenocytes gave rise to more CFUs, including granulocyte erythroid macrophage and megakaryocyte colonies (Table S1).

We performed BM transplantation (BMT) to test the functions of Tsc1-deficient HSCs. In serial BMT rescue experiments, we transplanted 106 WBM cells from either Tsc1fl/flmx-1-cre+ or Tsc1fl/flmx-1-cre− mice without pIpC treatment into lethally irradiated congenic CD45.1 recipients. Then we treated the recipients with pIpC every other day for 2 wk. After 12 more weeks, we killed the recipients and transplanted 3 × 106 WBM cells from the recipients into a second group of lethally irradiated CD45.1 recipients. Stem-cell functions were determined by testing the survival and hematopoiesis of the recipient mice, and donor-type cell reconstitution in the recipient peripheral blood at 6 wk after BMT (Fig. 3 a). As shown in Fig. 3 b, although all second recipients of the Ctrl BMT survived, only five out of nine recipients of Tsc1-deficient BM did, even though three times as many BM cells were used for the second BMT. Among the live secondary BMT recipients of the Tsc1-deficient BM, the majority of the CD45+ cells were of the recipient type (Fig. 3 c). Consistent with a defective hematopoiesis of the Tsc1-deficient HSCs, the primary BMT recipients showed a drastic reduction in the white blood cells at 3 mo after completion of the pIpC treatments, with reduction in essentially all cell types analyzed, as measured by the CBC test (Fig. 3 d).

Figure 3.

The Tsc1 deletion causes defective hematopoiesis. (a–d) Serial BMT reveals HSC-intrinsic defects. (a) Diagram of experimental design for data in b–d. (b) Tsc1-deficient BM cells are defective in rescuing lethally irradiated recipients in the second round, which indicate a reduced function of HSCs. 106 WBM cells were used for the first round of BMT, and 3 × 106 WBM cells were used for the second round of BMT. According to Fig. 1 f, 106 WBM cells from Tsc1-deficient mice contain ∼800 HSCs; those from Ctrl mice contain only ∼100 HSCs. For the WBM cells used for the second BMT, the frequency of HSCs was not analyzed. (c) Progressive loss of HSC activity as revealed by reduced replacement of recipient cells. Data shown are means ± SD of the percentage of donor cells in the blood of recipients at 6 wk after BMT (n = 15 for the first BMT, and n = 9 for the second BMT). (d) Reduced reconstitution of multiple lineages of blood cells by Tsc1fl/flmx-1-cre+ BM. Data shown are means ± SD of the relative number of cells in the blood, as measured by CBC. Data are normalized as the percentage of mean counts in mice reconstituted with WT BM. Summary data from two independent experiments involving a total of nine mice per group are presented. LY, lymphocytes; MO, monocytes; NE, neutrophils and eosinophils.

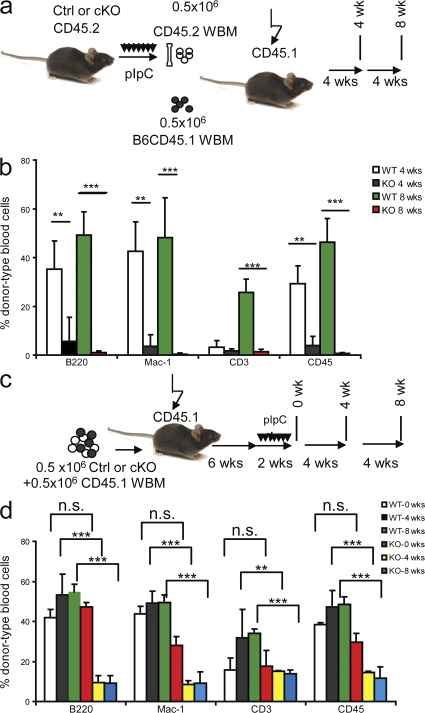

A more accurate method to evaluate the function of HSCs is to compare them with WT BM cotransferred into the same recipients. We used this strategy in two different settings. First, as diagramed in Fig. 4 a, BM cells were isolated as soon as the pIpC treatments were completed. The 1:1 mixtures of the CD45.2+ donor-type (either Ctrl or Tsc1fl/flmx-1-cre+) and CD45.1 recipient-type WT BM were transplanted into lethally irradiated congenic CD45.1 recipients. The reconstitutions in the recipient peripheral blood were analyzed at 4 and 8 wk after BMT by flow cytometry. As shown in Fig. 4 b, Ctrl BM cells contribute ∼30% in the peripheral blood of recipients at 4 wk after BMT, whereas Tsc1-deficient BM cells only contribute <5% (P < 0.0001). At 8 wk after BMT, the percentage of peripheral blood from the Ctrl donors further increased to ∼50%, whereas that from the mutant donors is reduced to <1%. Such reduction is evident among all of the lineages checked, including B cells, T cells, and myeloid cells. Thus, competitive BMT indicates that Tsc1-deficient HSCs have severely reduced function.

Figure 4.

Cell-intrinsic requirement for TSC1 in the function of HSCs. (a and b) Tsc1-deficient BM cells are dramatically less competent than WT BM cells in hematopoiesis when cotransferred into newly irradiated hosts. (a) The experimental designs. (b) The percentage of donor-type cells within the indicated populations at 4 or 8 wk after transplantation. Note that although the percentage of WT BM-derived cells progressively increased, those from Tsc-deficient BM reduced to background levels within 8 wk. Data shown are means ± SD (n = 5) and have been repeated twice. (c and d) Deletion of Tsc1 after establishment of BMT reveals a cell-intrinsic and homing-independent role for Tsc1 in the function of HSCs. (c) Experimental design. The Tsc1fl/flMX-Cre+ or Tsc1fl/flMX-Cre− BM were mixed at 1:1 with recipient-type BM and transferred into irradiated recipients. Tsc1 deletion is induced at 6 wk after transplantation. (d) Means ± SD (n = 5) of the percentage of donor-type cells in the blood at 4 or 8 wk after completion of pIpC treatments. The experiments have been repeated three times.

A potential caveat of this experiment is that the defects in the Tsc1-deficient HSCs can be caused by improper homing into the BM, as was observed in the Pten-deficient HSCs (6, 25). To overcome this caveat, we mixed either the Ctrl or the Tsc1fl/flmx-1-cre+ BM at a 1:1 ratio with recipient-type BM and transferred the cells into lethally irradiated mice. 6 wk later, when the HSCs have properly homed and stably reconstituted the recipients, the recipients were treated with pIpC to delete the Tsc1 gene in the Tsc1fl/flmx-1-cre+ hematopoietic cells only (Fig. 4 c). As shown in Fig. 4 d, at 0 wk after completion of treatments, there was no significant difference in the reconstitution rate by donor-type cells from Tsc1fl/flmx-1-cre+ and Tsc1fl/flmx-1-cre− mice. At both 4 and 8 wk after the treatments, we observed drastic reductions of Tsc1fl/flmx-1-cre+ BM-derived leukocytes (CD45+), particularly in B cells (B220+) and myeloid cells (Mac-1+; Fig. 4 d). Reflecting a slower turnover of the host T cell compartment, a gradual increase in the Ctrl T cells was observed after pIpC treatment. In contrast, neither an increase nor a reduction of T cells was observed at 4 and 8 wk after pIpC treatments in Tsc1-deficient BMT. The lack of reduction is likely caused by slow turnover of theTsc1fl/flmx-1-cre+ T cells produced before the pIpC treatment. Collectively, these data clearly demonstrated that the HSC-intrinsic expression of Tsc1 is essential for leukogenesis, and that the requirement of Tsc1 is HSC intrinsic.

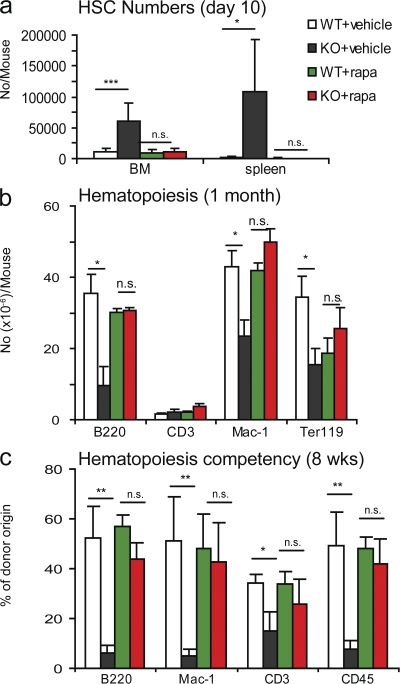

Functional rescue of HSC by rapamycin

Tsc1 is a known negative regulator for mTOR activity. To confirm the involvement of the mTOR pathway, we injected the pIpC-treated Tsc1fl/flmx-1-cre+ and Ctrl mice with rapamycin (4 mg per kilogram of bodyweight) every other day starting at the first pIpC treatment and continuing throughout the study. As shown in Fig. 5 a, the increase in the number of HSCs in both the BM and spleen of the pIpC-treated Tsc1fl/flmx-1-cre+ mice was completely inhibited by rapamycin. The number of B cells, myeloid cells, and, to a lesser extent, erythroid cells in the BM were also restored (Fig. 5 b). To confirm that rapamycin corrected the HSC-intrinsic, homing-independent defects, we repeated the BMT experiment depicted in Fig. 4 c and treated the mice with pIpC to delete Tsc1 in the presence of rapamycin. As shown in Fig. 5 c, rapamycin corrected the defects in all lineages of leukocytes. These data demonstrated that the TSC–mTOR pathway plays an essential role in the maintenance and in vivo functions of HSCs.

Figure 5.

Hematopoietic functions of the Tsc1-deficient HSCs (cKO) are restored by rapamycin treatment. (a) Rapamycin inhibited expansion of HSCs in the BM and in the spleen and restored normal hematopoiesis in the Tsc1-deficient BM. 6-wk-old Tsc1fl/flMX-Cre+ (cKO) or Tsc1fl/flMX-Cre− (Ctrl) mice were treated with pIpC for 2 wk. At the same time, the mice were treated with either vehicle Ctrl of 4 mg/kg rapamycin every other day throughout the entire period of the study. The HSC numbers shown were LSK cells at day 10 after completion of pIpC treatment. Similar restorations were observed on day 30. At both time points, the numbers of LT-HSCs were also reduced to normal levels (not depicted). (b) Rapamycin restores hematopoiesis in Tsc1-deficient BM. The data are the number of different lineages of cells from the BM collected at 30 d after pIpC treatments. Data shown were means ± SD (n = 4) from two independent experiments. (c) Rapamycin abrogates HSC-intrinsic functional defects caused by the deletion of Tsc1. The chimeric mice described in Fig. 4 c were treated with rapamycin, starting at the time of the pIpC treatment (4 mg/kg every other day, throughout the study). At 8 wk after completion of pIpC treatment, the mice were killed, and total and specific lineages of hematopoietic cells were analyzed by flow cytometry. Data shown are means ± SD of the percentage of cells of donor origin from two independent experiments (n = 10).

TSC1 maintains HSC function by repressing mitochondrion biogenesis and ROS production

As an essential integrator of multiple intrinsic and extrinsic signals, the TSC–mTOR pathway has been linked to many different downstream pathways, including protein synthesis, autophagy, transcription, and mitochondrial metabolism (21, 24). Because quiescent cells typically have reduced energy metabolism, we hypothesized that increased mitochondrion functions may epitomize the lack of quiescence observed after Tsc1 deletion. We have produced several lines of evidence to substantiate this hypothesis.

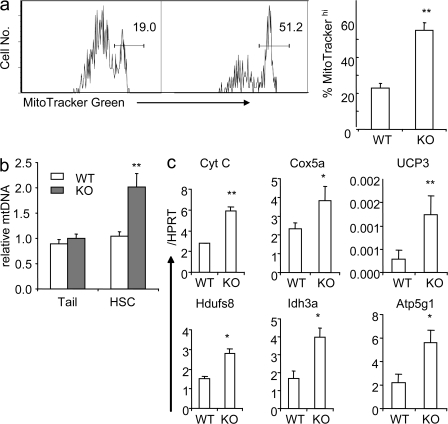

First, we measured the mitochondrion mass by flow cytometry with MitoTracker Green, which emits fluorescence only after binding to the mitochondrial lipid membrane (39). Our data demonstrated that >50% of the Tsc1-deficient HSCs had high mitochondrion contents, whereas <20% of the Ctrl HSC do (Fig. 6 a). By real-time PCR, we also found the number of mitochondrial DNA per HSC is almost doubled in pIpC-treated Tsc1fl/flmx-1-cre+ mice compared with that in the Ctrl (Fig. 6 b). Moreover, the transcripts of many mitochondrial genes that are involved in oxidative phosphorylation, including Cyt C, cox5a, Ucp3, Hdufs8, Ind3, and Atp5a1, are significantly up-regulated in Tsc1-deficient HSCs (Fig. 6 c).

Figure 6.

Up-regulated mitochondrial biogenesis in Tsc1-deficient, FLSKCD48− HSCs. (a) Tsc1 deletion results in increased mitochondrial biogenesis, as revealed by increased MitoTracker Green–high populations. (left) A representative FACS profile from one mouse BM LT-HSC is shown (numbers indicate percentages). (right) The summary data (means ± SD; n = 4) of the percentage of cells with high mitochondrion contents are shown. (b) Relative mitochondrion DNA contents in WT and Tsc1-deficient LT-HSCs. Mitochondrial DNA and genomic DNA were extracted from HSCs, and the copy number of mitochondrial DNA was measured by RT-PCR, normalized to genomic DNA. As a Ctrl, the mitochondrial DNA copy numbers from the tails of the Ctrl and mutant mice are measured. The mean abundance in Ctrl HSCs was defined as 1. Data shown are means ± SD (n = 3). (c) Up-regulation of the expressions of mitochondrial genes involved in oxidative phosphorylation in Tsc1-deficient HSCs. The mRNA levels of mitochondrial genes (Cyt C, Cox5a, UCP3, Hdufs8, Idh3a, and Atp5g1) are measured by real-time RT-PCR. Data shown were means ± SD of the fraction of Hprt copy numbers (n = 4). The data presented in this figure have been reproduced in at least four experiments.

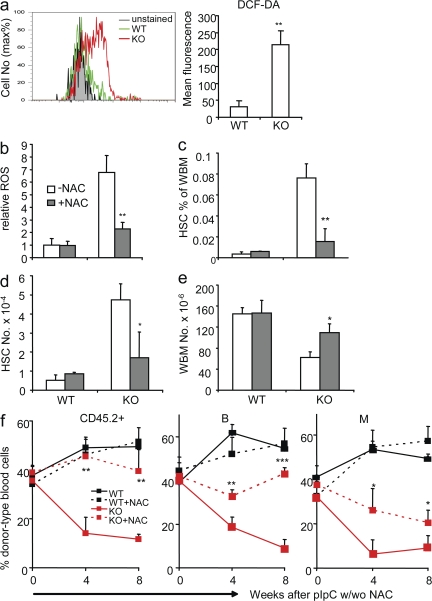

Second, mitochondrial oxidation may generate ROS. We therefore measured ROS levels in WT and Tsc1-deficient HSCs. 2',7'-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (DCF-DA) is an indicator of ROS levels because it is nonfluorescent until reacting with ROS inside the cells. In the Ctrl HSCs, ROS is repressed to very low levels. In contrast, the ROS level in the Tsc1-deficient HSCs was increased by approximately sevenfold, as indicated by flow cytometry of DCF-DA staining (Fig. 7 a).

Figure 7.

Tsc1 maintains the function of HSCs by repressing the production of ROS. (a) The Tsc1-deficient HSCs show dramatically increased levels of ROS, as indicated by DCF-DA staining. (left) Data shown are overlays of a FACS profile. (right) Data shown are means ± SD (n = 5) of the change in mean fluorescence after subtracting autofluorescences of HSCs. (b) ROS antagonist (NAC) treatment reduces the ROS level in Tsc1 mutant HSCs. Ctrl and Tsc1-deficient mice were treated with 1 mg/ml NAC in their drinking water in conjunction with pIpC treatment and were killed 10 d after the last pIpC injection. The BM cells were stained with HSC markers (FLSK) in conjunction with the ROS sensing dye DCF-DA. Data shown are relative levels of ROS. The mean fluorescence of untreated Ctrl HSCs is artificially defined as 1. Data shown are means ± SD (n = 4). (c) The BM cellularity in Tsc1 mutant mice is significantly rescued by NAC treatment. The BM cells used were as described in b. Data shown are means ± SD (n = 4). (d and e) The HSC frequency (d) and absolute number (e) in Tsc1 mutant mice were reduced to normal levels by NAC treatment. Results are as in b and c, except that the percentages and numbers of FLSK HSCs were analyzed. (f) In stable BM chimera consisting of WT and TSCfl/fl BM cells, the reconstitution capacity of Tsc1-deficient HSCs is significantly rescued by NAC treatment. Chimera mice depicted in Fig. 4 c were treated with NAC in their drinking water, starting at the same time of pIpC treatment. Blood samples were collected at the indicated time points and were analyzed by flow cytometry for the percentage of CD45.2+ donor cell types, B220+ B cells, and CD11b+ myeloid cells of donor type. Data shown are means ± SD from two independent experiments (n = 10).

ROS can be harmful to HSCs (26, 40–42). To test whether increased ROS is responsible for the lack of HSC function after Tsc1 deletion, we used N-acetylcysteine (NAC), a widely used antioxidant, to scavenge free radicals. We treated the mice with NAC in drinking water combined with pIpC treatment. 10 d after pIpC treatment, the ROS levels in Tsc1-deficient HSCs were repressed by NAC treatment, whereas those in Ctrl HSCs remained essentially undetectable (Fig. 7 b). The increases in both the frequency (Fig. 7 c) and absolute number (Fig. 7 d) of HSCs in the conditional Tsc1-deficient mice were largely abrogated by NAC treatment. Therefore, the increased ROS is likely an underlying cause for the increased proliferation of HSCs. NAC treatment also prevented Tsc1 deletion–induced BM hypocellularity (Fig. 7 e).

To directly test the role of ROS in Tsc1-deficient HSCs, we performed competitive BMT, as diagramed in Fig. 4 c. The recipients were given NAC water in conjunction with pIpC treatments. At 4 and 8 wk after pIpC treatment, the reconstitution rate of the total CD45.2+ donor-type peripheral blood cells in NAC-treated Tsc1fl/flmx-1-cre+ BM recipients was ∼45%, which is comparable to that of Ctrl BM. In contrast, the untreated Tsc1fl/flmx-1-cre+ BM recipients have <10% of donor-type CD45+ cells. This is reflected in the rescue of all major lineages (Fig. 7 f). Therefore, NAC treatment, which inhibited ROS in Tsc1-deficient HSCs, restored the HSC in vivo functions. These data strongly indicate that ROS is a major target of the TSC–mTOR pathway in HSCs.

DISCUSSION

The mTOR pathway has emerged as a central regulator for cellular growth, differentiation, and energy response (21). However, despite the extensive use of the mTOR inhibitors for immune suppression, the function of mTOR in the hematopoietic system has not been analyzed genetically. In this paper, we showed that the targeted mutation of Tsc1, an essential and specific negative regulator of mTOR complex 1 (31, 32) (for review see reference 33), abrogated the quiescence and function of HSCs.

Tsc1 as an essential negative regulator for the quiescence of HSCs

Because germline mutations of Tsc1 are embryonically lethal, we used the MX1-Cre transgene to induce deletion of Tsc1 in the adult mice. Recent studies have demonstrated that this approach leads to a nearly complete deletion of genes in the HSCs (6, 25), as we have demonstrated in the case of Tsc1. Using pS6 protein as a marker for mTOR activation, our data demonstrated a dramatic elevation of mTOR activity in the HSCs after the Tsc1 deletion.

In conjunction with mTOR activation, we observed a massive increase in HSC proliferation, RNA synthesis, mitochondrial biogenesis, and the production of ROS. Although it has been well established that adult HSCs divide slowly (1–6), the pathway that keeps them in the G0 phase has been largely unclear. Our data demonstrate that the TSC–mTOR pathway plays an essential role in keeping HSC in G0 phase. Increased proliferation of the HSCs has also been observed after a targeted mutation of the Pten gene in the HSCs (6, 25). Because Pten is a negative regulator of the PI3K–AKT pathway, which in turn stimulates mTOR by inactivating the TSC complex (31, 32), it is likely that the inactivation of TSC1 is at least in part responsible for Pten-induced hyperproliferation of HSCs. On the other hand, a targeted mutation of p21 is also known to induce hyperproliferation of HSCs (5). Because the Tsc1−/− HSCs actually had slightly higher levels of p21 transcript (unpublished data), a lack of quiescence of Tsc1−/− HSCs cannot be caused by a reduction in p21 expression.

Overactivation of mTOR alone is insufficient to cause hematological malignancies in the mice

Part of the phenotypes we presented in this paper, including the increased proliferation and lost functions, are consistent with those reported in the Pten-deficient HSCs (6, 25). Thus, even though it has been argued that the PI3K–Akt pathway regulates the HSCs mainly through FOXOs instead of mTOR (40), our data are consistent with the notion that in HSCs, Pten is also an upstream regulator of the TSC–mTOR pathway, as revealed in other models (33). However, there are significant differences between Tsc1-deficient HSCs and Pten-deficient HSCs. Although Pten deletion promotes severe myeloproliferative disease within days (6, 25), we did not observe leukemia or other malignancies in mice with Tsc1 deletion in HSCs. Nor did we observe a single case of leukemia in BMT recipients when the Tsc1-deficient BM was serially transplanted over a 1-yr period after Tsc1 deletion. Flow cytometry analysis also found no myeloid dysplasia, as reported in mice with a conditional deletion of the Pten gene (unpublished data). The inability of Tsc1 mutation to cause cancer is supported by a general lack of cancer among TSC patients (33). However, our data did not rule out the possibility that Tsc1 deletion can provide one of several genetic changes necessary for tumorigenesis in the Pten-deficient BM.

It should be noted that the Pten protein resides in distinct cellular pools and can mediate functions other than regulating the TSC–mTOR pathway (43–45). In addition, because of the feedback of S6 kinase to insulin receptor substrate 1, Akt is activated by Pten deletion but inhibited in Tsc mutants (46). The transformation of HSCs by Pten deletion might also be explained by the nuclear functions of Pten to maintain chromosomal integrity and/or activation of Akt (44). It remains to be investigated which pathway explains the difference in phenotypes after the deletion of Pten versus Tsc1.

An explanation for the requirement of stem cell niches and quiescence for maintaining the long-term function of HSCs

Notably, previous studies on the quiescence of HSCs have been limited to cell-cycle regulation. Hyperproliferation by itself, however, does not necessarily inhibit stem cell function, as fetal HSCs do divide at a high rate (47). Our data provide a missing link between the Tsc–mTOR pathway and mitochondrial biogenesis, and up-regulation of genes involved in oxidative function in the HSCs. Perhaps because of unbalanced production and removal, ROS levels increased dramatically in the Tsc1-deficient HSCs, which we show to be responsible for defects in HSC function. Recently, Suzuki et al. (48) reported a very modest increase (7% over Ctrl) of ROS activity when Tsc2 mutants were ectopically expressed in COS cells, and argued that this gain of function relates to Rac activation but is independent of Tsc1 loss and is, therefore, presumably independent of mTOR activation. It remains to be tested whether the pathway uncovered in our study is unique for HSCs.

Because the HSCs are highly sensitive to ROS (26, 40–42), they are not programmed to neutralize products associated with active metabolism. Therefore, our study provides a novel explanation on why HSCs must remain quiescent to maintain their “stemness.”

Because the mTOR pathway is regulated by glucose, nutrients, and O2 levels (21), it would be of great interest to determine whether abnormal mTOR activation is the underlying cause for the loss of quiescence in HSCs after disruption of the stem cell niche in vivo (36–38). In toto, our data suggest mTOR activation as a unifying explanation of the requirements of HSC niche and quiescence in HSC function.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice.

Tsc1fl/fl mice (49) were provided by D.J. Kwiatkowski (Brigham and Women's Hospital, Boston, MA) and were backcrossed for six generations onto the C57BL/6 background in the animal facility at the University of Michigan. Mx-1-cre mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (50). Recipients in reconstitution assays were 8-wk-old B6ly5.2 mice from the National Cancer Institute. All procedures involving experimental animals were approved by the University Committee on the Use and Care of Animals at the University of Michigan.

pIpC, rapamycin, and NAC treatment.

pIpC (Sigma-Aldrich) was resuspended in PBS at 1 mg/ml. Mice received 15 mg/kg of pIpC every other day seven times by i.p. injection (51). Rapamycin (Sigma-Aldrich) was reconstituted in absolute ethanol at 10 mg/ml and diluted in 5% Tween-80 (Sigma-Aldrich) and 5% PEG-400 (Hampton Research). Mice received 4 mg/kg rapamycin by i.p. injection every other day. NAC (Sigma-Aldrich) was delivered through feeding water at 1 mg/ml.

Flow cytometry.

BM cells were flushed by a 25-gauge needle from the long bones (tibias and femurs) with HBSS without calcium or magnesium (Invitrogen), supplemented with 2% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum. Peripheral blood was obtained from the tail veins of recipients at the time points indicated in the figures, and RBCs were lysed by ammonium chloride/potassium bicarbonate buffer before staining.

For flow cytometry and purification of HSCs, the FLSKCD48− phenotype is used for LT-HSCs, and the Lin−Sca-1+c-kit+CD48+ phenotype is used for short-term HSCs (34). Lineage markers included B220, CD3, Gr-1, Mac-1, and Ter119 (BD Biosciences). Flow cytometry analysis was performed on an LSR II (BD Biosciences), and FACS was performed on a FACSAria (BD Biosciences). All other antibodies were obtained from eBioscience.

For pS6 staining, BM cells were stained with the surface markers and fixed with fix/permealization buffer (BD Biosciences), and then incubated with Alexa Fluor 488–conjugated pS6 antibodies (Cell Signaling Technology) for 2 h in ice. The samples were analyzed by flow cytometry after the removal of unbound antibodies.

To determine the RNA/DNA content, fresh BM cells were stained with surface markers for HSCs and fixed in cold 70% ethanol overnight at −20°C. 4 μg/ml pyronin Y (Sigma-Aldrich) and 2 μg/ml HOECHST 33342 (Sigma-Aldrich) were stained for 30 min at 4°C.

BrdU (BD Biosciences) was injected i.p. into adults at 100 mg/kg. The mice were then given 1 mg/ml BrdU water for 24 h and killed for analysis. BrdU staining was performed according to the producer's manual.

MitoTracker Green (Invitrogen) was stained at 50 nM for 15 min at 37°C after staining of surface markers. ROS was measured by DCF-DA (Invitrogen) staining at 10 μM for 15 min at 37°C after staining of surface markers, according to the manufacturer's manual.

BMT.

8-wk-old recipient mice were lethally irradiated with a Cs-137 x-ray source delivering 180 rads per min, for a combined 1,100 rads, delivered >2 h apart. Donor WBM cells with or without competitive recipient-type WBM cells were transplanted into recipients through the retroorbital venous sinus 24 h after irradiation. Reconstitutions were measured by flow cytometry of peripheral blood from the recipient tail vein at the time points indicated in the figures.

CFU assay.

WBM cells or splenocytes isolated from Tsc1fl/fl or Tsc1fl/flmx-1-cre+ mice 10 d after pIpC treatment were plated into MethoCult GFM3434 (StemCell Technologies, Inc.) and cultured for 12 d before counting under a microscope (CKX31; Olympus).

Statistics.

The function of HSCs in the rescue of lethal irradiation was compared by a Kaplan-Meier survival analysis, and the p-value of the log-rank tests are provided either in the figures or in the figure legends. Student's t tests were used for all other analyses (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001).

Online supplemental material.

Table S1 shows a colony-forming assay of WBM cells and splenocytes from WT and KO mice. Fig. S1 depicts BrdU incorporation of WBM cells and Lin− cells in WT and KO mice. Online supplemental material is available at http://www.jem.org/cgi/content/full/jem.20081297/DC1.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. David J. Kwiatkowski for the Tsc1fl/fl mice, Shenghui He and Dr. Mark Kiel for technical help and discussions, Todd Brown for editorial assistance, and Drs. Yuan Zhu, Jun-Lin Guan, and Jiandie Lin for critical reading of the manuscript and/or helpful discussions.

This study is supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health, the United States Department of Defense, and the American Cancer Society, and a gift fund of the University of Michigan Comprehensive Cancer Center.

The authors have no financial conflict of interest.

Abbreviations used: BMT, BM transplantation; CBC, complete blood cell count; Ctrl, control; DCF-DA, 2',7'-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate; FLSK, Flt2−Lin−Sca-1+c-Kit+; HSC, hematopoietic stem cell; LT-HSC, long-term HSC; mTOR, mammalian TOR; NAC, N-acetylcysteine; PI3K, phosphoinositide 3-kinase; pIpC, polyinosine-polycytidine; ROS, reactive oxygen species; TOR, target of rapamycin; TSC, tuberous sclerosis complex; WBM, whole BM.

References

- 1.Ogawa, M. 1993. Differentiation and proliferation of hematopoietic stem cells. Blood. 81:2844–2853. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lajtha, L.G. 1963. On the concept of the cell cycle. J. Cell. Physiol. 62(Suppl. 1):143–145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lajtha, L.G. 1979. Stem cell concepts. Differentiation. 14:23–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang, J., C. Niu, L. Ye, H. Huang, X. He, W.G. Tong, J. Ross, J. Haug, T. Johnson, J.Q. Feng, et al. 2003. Identification of the haematopoietic stem cell niche and control of the niche size. Nature. 425:836–841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cheng, T., N. Rodrigues, H. Shen, Y. Yang, D. Dombkowski, M. Sykes, and D.T. Scadden. 2000. Hematopoietic stem cell quiescence maintained by p21cip1/waf1. Science. 287:1804–1808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang, J., J.C. Grindley, T. Yin, S. Jayasinghe, X.C. He, J.T. Ross, J.S. Haug, D. Rupp, K.S. Porter-Westpfahl, L.M. Wiedemann, et al. 2006. PTEN maintains haematopoietic stem cells and acts in lineage choice and leukaemia prevention. Nature. 441:518–522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schofield, R. 1978. The relationship between the spleen colony-forming cell and the haemopoietic stem cell. Blood Cells. 4:7–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wilson, A., and A. Trumpp. 2006. Bone-marrow haematopoietic-stem-cell niches. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 6:93–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nilsson, S.K., H.M. Johnston, and J.A. Coverdale. 2001. Spatial localization of transplanted hemopoietic stem cells: inferences for the localization of stem cell niches. Blood. 97:2293–2299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chow, D.C., L.A. Wenning, W.M. Miller, and E.T. Papoutsakis. 2001. Modeling pO(2) distributions in the bone marrow hematopoietic compartment. II. Modified Kroghian models. Biophys. J. 81:685–696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cipolleschi, M.G., P. Dello Sbarba, and M. Olivotto. 1993. The role of hypoxia in the maintenance of hematopoietic stem cells. Blood. 82:2031–2037. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ivanovic, Z., B. Bartolozzi, P.A. Bernabei, M.G. Cipolleschi, E. Rovida, P. Milenkovic, V. Praloran, and P. Dello Sbarba. 2000. Incubation of murine bone marrow cells in hypoxia ensures the maintenance of marrow-repopulating ability together with the expansion of committed progenitors. Br. J. Haematol. 108:424–429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Parmar, K., P. Mauch, J.A. Vergilio, R. Sackstein, and J.D. Down. 2007. Distribution of hematopoietic stem cells in the bone marrow according to regional hypoxia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 104:5431–5436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Simon, M.C., and B. Keith. 2008. The role of oxygen availability in embryonic development and stem cell function. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 9:285–296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang, X., J. Li, D.P. Sejas, and Q. Pang. 2005. Hypoxia-reoxygenation induces premature senescence in FA bone marrow hematopoietic cells. Blood. 106:75–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brugarolas, J., K. Lei, R.L. Hurley, B.D. Manning, J.H. Reiling, E. Hafen, L.A. Witters, L.W. Ellisen, and W.G. Kaelin Jr. 2004. Regulation of mTOR function in response to hypoxia by REDD1 and the TSC1/TSC2 tumor suppressor complex. Genes Dev. 18:2893–2904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ellisen, L.W. 2005. Growth control under stress: mTOR regulation through the REDD1-TSC pathway. Cell Cycle. 4:1500–1502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pouyssegur, J., F. Dayan, and N.M. Mazure. 2006. Hypoxia signalling in cancer and approaches to enforce tumour regression. Nature. 441:437–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reiling, J.H., and E. Hafen. 2004. The hypoxia-induced paralogs Scylla and Charybdis inhibit growth by down-regulating S6K activity upstream of TSC in Drosophila. Genes Dev. 18:2879–2892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sofer, A., K. Lei, C.M. Johannessen, and L.W. Ellisen. 2005. Regulation of mTOR and cell growth in response to energy stress by REDD1. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25:5834–5845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wullschleger, S., R. Loewith, and M.N. Hall. 2006. TOR signaling in growth and metabolism. Cell. 124:471–484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Martin, D.E., and M.N. Hall. 2005. The expanding TOR signaling network. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 17:158–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sarbassov, D.D., S.M. Ali, and D.M. Sabatini. 2005. Growing roles for the mTOR pathway. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 17:596–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cunningham, J.T., J.T. Rodgers, D.H. Arlow, F. Vazquez, V.K. Mootha, and P. Puigserver. 2007. mTOR controls mitochondrial oxidative function through a YY1-PGC-1alpha transcriptional complex. Nature. 450:736–740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yilmaz, O.H., R. Valdez, B.K. Theisen, W. Guo, D.O. Ferguson, H. Wu, and S.J. Morrison. 2006. Pten dependence distinguishes haematopoietic stem cells from leukaemia-initiating cells. Nature. 441:475–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jang, Y.Y., and S.J. Sharkis. 2007. A low level of reactive oxygen species selects for primitive hematopoietic stem cells that may reside in the low-oxygenic niche. Blood. 110:3056–3063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.The European Chromosome 16 Tuberous Sclerosis Consortium. 1993. Identification and characterization of the tuberous sclerosis gene on chromosome 16. Cell. 75:1305–1315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van Slegtenhorst, M., R. de Hoogt, C. Hermans, M. Nellist, B. Janssen, S. Verhoef, D. Lindhout, A. van den Ouweland, D. Halley, J. Young, et al. 1997. Identification of the tuberous sclerosis gene TSC1 on chromosome 9q34. Science. 277:805–808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gao, X., and D. Pan. 2001. TSC1 and TSC2 tumor suppressors antagonize insulin signaling in cell growth. Genes Dev. 15:1383–1392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Potter, C.J., H. Huang, and T. Xu. 2001. Drosophila Tsc1 functions with Tsc2 to antagonize insulin signaling in regulating cell growth, cell proliferation, and organ size. Cell. 105:357–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Inoki, K., Y. Li, T. Zhu, J. Wu, and K.L. Guan. 2002. TSC2 is phosphorylated and inhibited by Akt and suppresses mTOR signalling. Nat. Cell Biol. 4:648–657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Potter, C.J., L.G. Pedraza, and T. Xu. 2002. Akt regulates growth by directly phosphorylating Tsc2. Nat. Cell Biol. 4:658–665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Inoki, K., M.N. Corradetti, and K.L. Guan. 2005. Dysregulation of the TSC-mTOR pathway in human disease. Nat. Genet. 37:19–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kiel, M.J., O.H. Yilmaz, T. Iwashita, C. Terhorst, and S.J. Morrison. 2005. SLAM family receptors distinguish hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells and reveal endothelial niches for stem cells. Cell. 121:1109–1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Spradling, A., D. Drummond-Barbosa, and T. Kai. 2001. Stem cells find their niche. Nature. 414:98–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Arai, F., A. Hirao, M. Ohmura, H. Sato, S. Matsuoka, K. Takubo, K. Ito, G.Y. Koh, and T. Suda. 2004. Tie2/angiopoietin-1 signaling regulates hematopoietic stem cell quiescence in the bone marrow niche. Cell. 118:149–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fleming, H.E., V. Janzen, C. Lo Celso, J. Guo, K.M. Leahy, H.M. Kronenberg, and D.T. Scadden. 2008. Wnt signaling in the niche enforces hematopoietic stem cell quiescence and is necessary to preserve self-renewal in vivo. Cell Stem Cell. 2:274–283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yoshihara, H., F. Arai, K. Hosokawa, T. Hagiwara, K. Takubo, Y. Nakamura, Y. Gomei, H. Iwasaki, S. Matsuoka, K. Miyamoto, et al. 2007. Thrombopoietin/MPL signaling regulates hematopoietic stem cell quiescence and interaction with the osteoblastic niche. Cell Stem Cell. 1:685–697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pendergrass, W., N. Wolf, and M. Poot. 2004. Efficacy of MitoTracker Green and CMXrosamine to measure changes in mitochondrial membrane potentials in living cells and tissues. Cytometry A. 61A:162–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tothova, Z., R. Kollipara, B.J. Huntly, B.H. Lee, D.H. Castrillon, D.E. Cullen, E.P. McDowell, S. Lazo-Kallanian, I.R. Williams, C. Sears, et al. 2007. FoxOs are critical mediators of hematopoietic stem cell resistance to physiologic oxidative stress. Cell. 128:325–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ito, K., A. Hirao, F. Arai, K. Takubo, S. Matsuoka, K. Miyamoto, M. Ohmura, K. Naka, K. Hosokawa, Y. Ikeda, and T. Suda. 2006. Reactive oxygen species act through p38 MAPK to limit the lifespan of hematopoietic stem cells. Nat. Med. 12:446–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ito, K., A. Hirao, F. Arai, S. Matsuoka, K. Takubo, I. Hamaguchi, K. Nomiyama, K. Hosokawa, K. Sakurada, N. Nakagata, et al. 2004. Regulation of oxidative stress by ATM is required for self-renewal of haematopoietic stem cells. Nature. 431:997–1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Trotman, L.C., X. Wang, A. Alimonti, Z. Chen, J. Teruya-Feldstein, H. Yang, N.P. Pavletich, B.S. Carver, C. Cordon-Cardo, H. Erdjument-Bromage, et al. 2007. Ubiquitination regulates PTEN nuclear import and tumor suppression. Cell. 128:141–156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shen, W.H., A.S. Balajee, J. Wang, H. Wu, C. Eng, P.P. Pandolfi, and Y. Yin. 2007. Essential role for nuclear PTEN in maintaining chromosomal integrity. Cell. 128:157–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cully, M., H. You, A.J. Levine, and T.W. Mak. 2006. Beyond PTEN mutations: the PI3K pathway as an integrator of multiple inputs during tumorigenesis. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 6:184–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Inoki, K., and K.L. Guan. 2006. Complexity of the TOR signaling network. Trends Cell Biol. 16:206–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bowie, M.B., K.D. McKnight, D.G. Kent, L. McCaffrey, P.A. Hoodless, and C.J. Eaves. 2006. Hematopoietic stem cells proliferate until after birth and show a reversible phase-specific engraftment defect. J. Clin. Invest. 116:2808–2816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Suzuki, T., S.K. Das, H. Inoue, M. Kazami, O. Hino, T. Kobayashi, R.S. Yeung, K. Kobayashi, T. Tadokoro, and Y. Yamamoto. 2008. Tuberous sclerosis complex 2 loss-of-function mutation regulates reactive oxygen species production through Rac1 activation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 368:132–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Uhlmann, E.J., M. Wong, R.L. Baldwin, M.L. Bajenaru, H. Onda, D.J. Kwiatkowski, K. Yamada, and D.H. Gutmann. 2002. Astrocyte-specific TSC1 conditional knockout mice exhibit abnormal neuronal organization and seizures. Ann. Neurol. 52:285–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kuhn, R., F. Schwenk, M. Aguet, and K. Rajewsky. 1995. Inducible gene targeting in mice. Science. 269:1427–1429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mikkola, H.K., J. Klintman, H. Yang, H. Hock, T.M. Schlaeger, Y. Fujiwara, and S.H. Orkin. 2003. Haematopoietic stem cells retain long-term repopulating activity and multipotency in the absence of stem-cell leukaemia SCL/tal-1 gene. Nature. 421:547–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.